Indus–Mesopotamia relations

Indus–Mesopotamia relations are thought to have developed during the second half of 3rd millennium BCE, until they came to a halt with the extinction of the Indus valley civilization after around 1900 BCE.[6][7][8] Mesopotamia had already been an intermediary in the trade of lapis lazuli between the Indian subcontinent and Egypt since at least about 3200 BCE, in the context of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.[9][10]

Neolithic expansion (9000–6500 BCE)

A first period of indirect contacts seems to have occurred as a consequence of the Neolithic Revolution and the diffusion of agriculture after 9000 BCE. [lower-alpha 1] The prehistoric agriculture of the Indian subcontinent is thought to have combined local resources, such as humped cattle, with agricultural resources from the Near East as a first step in the 8th–7th millennium BCE, to which were later added resources from Africa and East Asia from the 3rd millennium BCE.[13] Mehrgarh is one of the earliest sites with evidence of farming and herding in the subcontinent.[15][16][lower-alpha 2] At Mehrgarh, around 7000 BCE, the full set of Near Eastern incipient agricultural products can be found: wheat, barley, as well as goats, sheep and cattle.[13] The rectangular houses of Mehrgarh as well as the female figurines are essentially identical with those of the Near East.[13]

The Near-Eastern origin of South Asian agriculture is generally accepted, and it has been the "virtual archaeological dogma for decades".[26] Gregory Possehl however argues for a more nuanced model, in which the early domestication of plant and animal species may have occurred in a wide area from the Mediterranean to the Indus, in which new technology and ideas circulated fast and were widely shared.[27] Today, the main objection to this model lies in the fact that wild wheat has never been found in South Asia, suggesting that either wheat was first domesticated in the Near-East from well-known domestic wild species and then brought to South Asia, or that wild wheat existed in the past in South Asia but somehow became extinct without leaving a trace.[27]

Jean-François Jarrige argues for an independent origin of Mehrgarh. Jarrige notes "the assumption that farming economy was introduced full-fledged from Near-East to South Asia,"[28][lower-alpha 3] and the similarities between Neolithic sites from eastern Mesopotamia and the western Indus valley, which are evidence of a "cultural continuum" between those sites. But given the originality of Mehrgarh, Jarrige concludes that Mehrgarh has an earlier local background, and is not a "'backwater' of the Neolithic culture of the Near East."[28]

Land and maritime relations

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)

Sea levels have been rising about 100 meters over the last 15,000 years until modern times, with the effect that coast lines have been receding vastly. This is especially the case of the coast lines of the Indus and Mesopotamia, which were originally only separated by a distance of about 1000 kilometers, compared to 2000 kilometers today.[1] For the ancestors of the Sumerians, the distance between the coasts of the Mesopotamian area and the Indus area would have been much shorter than it is today.[1] In particular the Persian Gulf, which is only about 30 meters deep today, would have been at least partially dry, and would have formed an extension of the Mesopotamian basin.[1]

The westernmost Harappan city was located on the Makran coast at Sutkagan Dor, near the tip of the Arabian peninsula, and is considered as an ancient maritime trading station, probably between modern day Pakistan and the Persian Gulf.[45]

Sea-going vessels were known in the Indus region, as shown by seals showing ships with land-finding birds (disha-kaka), dating to 2500-1750 BCE.[50] When a boat was lost at sea, with land beyond the horizon, birds released by the mariners would securely fly back to land, and therefore show the boats the way to safety.[50] Various stamp seals are known from the Indus and the Persian Gulf area, with depictions of large ships pertaining to different shipbuilding traditions.[51] Sargon of Akkad (c. 2334–2284 BCE) claimed in one of his inscriptions that "ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun made fast at the docks of Akkad".[51]

Commercial and cultural exchanges

Many archaeological finds suggest that maritime trade along the shores of Africa and Asia started several millennia ago.[52] Indus pottery and seals have been found along the sea routes between the Indus and Mesopotamia, as in Ras al-Jinz, at the tip of Arabia.[53][54]

Indus imports into Mesopotamia

.jpg.webp)

Clove heads, thought to originate from the Moluccas in Maritime Southeast Asia were found in a 2nd millennium BCE site in Terqa.[52] Evidence for imports from the Indus to Ur can be found from around 2350 BCE.[52] Various objects made with shell species that are characteristic of the Indus coast, particularly Trubinella Pyrum and Fasciolaria Trapezium, have been found in the archaeological sites of Mesopotamia dating from around 2500-2000 BCE.[56][7] Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450.[57] In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique of acid-etching developed by the Harappans.[58][55][59] Lapis Lazuli was imported in great quantity by Egypt, and already used in many tombs of the Naqada II period (circa 3200 BCE). Lapis Lazuli probably originated in northern Afghanistan, as no other sources are known from that time, and had to be transported across the Iranian plateau to Mesopotamia, and then Egypt.[9][10]

Several Indus seals with Harappan script have also been found in Mesopotamia, particularly in Ur, Babylon and Kish.[60][61][62][63][64][65] The water buffalos that appear on Akkadian cylinder seals from the time of Naram-Sin (circa 2250 BCE) may have been imported to Mesopotamia from the Indus as a result of trade.[5][2][4]

Akkadian Empire records mention timber, carnelian and ivory as being imported from Meluhha by Meluhhan ships, Meluhha being generally considered as the Mesopotamian name for the Indus Valley.[57][7]

‘The ships from Meluhha, the ships from Magan, the ships from Dilmun, he made tie-up alongside the quay of Akkad’

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, is recorded as having imported "translucent carnelian" from Meluhha.[57] Various inscriptions also mention the presence of Meluhha traders and interpreters in Mesopotamia.[57] About twenty seals have been found from the Akkadian and Ur III sites, that have connections with Harappa and often use Harappan symbols or writing.[57]

A modern impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa, in strata dated to 2600-1700 BCE. Elongated buffalo with line of standard Indus script signs. Tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 2425.[68][69] Indus script numbering convention per Asko Parpola.[70][71]

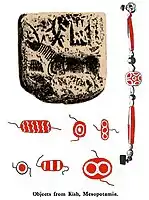

A modern impression of an Indus cylinder seal discovered in Susa, in strata dated to 2600-1700 BCE. Elongated buffalo with line of standard Indus script signs. Tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 2425.[68][69] Indus script numbering convention per Asko Parpola.[70][71] Indus Valley "Unicorn" seal and etched carnelian beads excavated in Kish by Ernest J. H. Mackay, Mesopotamia, early Sumerian period stratification, circa 3000 BCE.[72][73][74][75]

Indus Valley "Unicorn" seal and etched carnelian beads excavated in Kish by Ernest J. H. Mackay, Mesopotamia, early Sumerian period stratification, circa 3000 BCE.[72][73][74][75]

Indus round seal with impression. Elongated buffalo with Harappan script imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 5614[79]

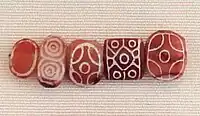

Indus round seal with impression. Elongated buffalo with Harappan script imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 5614[79] Indian carnelian beads with white design, etched in white with an alkali through a heat process, imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 17751.[80][81][82] These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira.[83]

Indian carnelian beads with white design, etched in white with an alkali through a heat process, imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 17751.[80][81][82] These beads are identical with beads found in the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira.[83] Indus bracelet, front and back, made of Fasciolaria Trapezium or Xandus Pyrum imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473.[84] This type of bracelet was manufactured in Mohenjo-daro, Lothal and Balakot.[59] The back is engraved with an oblong chevron design which is typical of shell bangles of the Indus Civilization.[85]

Indus bracelet, front and back, made of Fasciolaria Trapezium or Xandus Pyrum imported to Susa in 2600-1700 BCE. Found in the tell of the Susa acropolis. Louvre Museum, reference Sb 14473.[84] This type of bracelet was manufactured in Mohenjo-daro, Lothal and Balakot.[59] The back is engraved with an oblong chevron design which is typical of shell bangles of the Indus Civilization.[85].jpg.webp)

Similar Harappan weights found in the Indus Valley. New Delhi Museum.[88]

Similar Harappan weights found in the Indus Valley. New Delhi Museum.[88] A rare etched carnelian bead found in Egypt, thought to have been imported from the Indus Valley civilization through Mesopotamia. Late Middle Kingdom. London, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, ref. UC30334.[89][90]

A rare etched carnelian bead found in Egypt, thought to have been imported from the Indus Valley civilization through Mesopotamia. Late Middle Kingdom. London, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, ref. UC30334.[89][90]

Mesopotamian imports into the Indus

Possible iconographical influences

Various authors have described possible iconographical influences from Mesopotamia to the Indus Valley.[98] Gregory Possehl notes "Mesopotamian themes in Indus iconography", particularly designs related to the Gilgamesh epic, suggesting that "some aspects of Mesopotamian religion and ideology would have been accepted at face value is a reasonable notion".[99] Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi also describes the presence of Gilgamesh on Indus seals.[100] In the archaeological sites of the Indus valley civilization, twenty-four stone haematite weights of the Mesopotamian barrel-shaped type were found at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa.[101]

There are also many instances of influence the other way round, in which Indus Valley seals and designs have been found in Mesopotamia.

Indus Valley stamp seals

Some Indus seals seem to show possible Mesopotamian influence, as in the "Gilgamesh" motif of a man fighting two lions (2500-1500 BCE).[93][94][102]

Several Indus Valley seals show a fighting scene between a tiger-like beast and a man with horns, hooves and a tail, who has been compared to the Mesopotamian bull-man Enkidu, also a partner of Gilgamesh, and suggests a transmission of Mesopotamian mythology.[95][103][97]

Cylinder seals

A few rare cylinder seals have been found in Indus valley sites, which suggest Mesopotamian influence: they were probably made locally, but they use Mesopotamian motifs.[104] One such cylinder seal, the Kalibangan seal, shows a battle between men in the presence of centaurs.[105][106] Other seals show processions of animals.[106]

Others have suggested that the cylinder seals show the Indus valley's influence on Mesopotamia. These may have been due to overland trade between the two cultures.[107]

A rare Indus Valley civilization cylinder seal composed of two animals with a tree or bush in front. Such cylinder seals are indicative of contacts with Mesopotamia.[110]

A rare Indus Valley civilization cylinder seal composed of two animals with a tree or bush in front. Such cylinder seals are indicative of contacts with Mesopotamia.[110]

Indian genes in ancient Mesopotamia

It has long been suggested that the Sumerians, who ruled in Lower Mesopotamia from circa 4500 to 1900 BCE and who spoke a non-Indo-European and non-Semitic language, may have initially come from India.[115][116] This appeared to historian Henry Hall as the most probable conclusion, particularly based on the portrayal of Sumerians in their own art and "how very Indian the Sumerians were in type".[115] Recent genetic analysis of ancient Mesopotamian skeletal DNA tends to confirm a significant association.[117] The Sumerians progressively lost control to Semitic states from the northwest, starting with the Akkadian Empire, from circa 2300 BCE.

Methodology

A genetic analysis of the ancient DNA of Mesopotamian skeletons was made on the excavated remains of four individuals from ancient tombs in Tell Ashara (ancient Terqa) and Tell Masaikh (near Terqa, also known as ancient Kar-Assurnasirpal), both in the middle Euphrates valley in the east of modern Syria.[117] The two oldest skeletons were dated to 2,650-2,450 BCE and 2,200-1,900 BCE respectively, while the two younger skeletons were dated to circa 500 AD.[117] All the studied individuals carried mtDNA haplotypes corresponding to the M4b1, M49 and/or M61 haplogroups, which are believed to have arisen in the area of the Indian subcontinent during the Upper Paleolithic, and are absent in people living today in Syria.[117] These haplogroups are still present in people inhabiting today's Tibet, Himalayas (Ladakh), India and Pakistan, and are restricted today to the South, East and Southeast Asia regions.[117] The data suggests a genetic link of the region with the Indian subcontinent in the past that has not left traces in the modern population of Mesopotamia.[117]

Other studies have also shown connections between the populations of Mesopotamia and population groups now located in Southern India, such as the Tamils.[120][121]

Analysis

The genetic analysis suggests that a continuity existed between Trans-Himalaya and Mesopotamia regions in ancient time, and that the studied individuals represent genetic associations with the Indian subcontinent.[117] It is likely that this genetic connection was broken as a result of population movements during more recent times.[117]

The fact that the studied individuals comprised both males and a female, each living in a different period and representing different haplotypes, suggests that the nature of their presence in Mesopotamia was long-lasting rather than incidental.[117] The close ancestors of the specimens could fall within the population founding Terqa, a historical site that was probably constructed during the early Bronze Age, at a time only slightly preceding the dating of the skeletons.[117]

The studied individuals could also have been the descendants of much earlier migration waves who brought these genes from the Indian subcontinent.[117] It cannot be excluded that among them were people involved in the founding of the Mesopotamian civilizations.[117] For instance, it is commonly accepted that the founders of Sumerian civilization may have come from outside the region, but their exact origin is still a matter of debate.[117] The migrants could have entered Mesopotamia earlier than 4,500 years ago, during the lifetime of the oldest studied individual.[117] Alternatively, the studied individuals may have belonged to groups of itinerant merchants moving along a trade route passing near or through the region.[117]

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BCE.

Enthroned Sumerian king of Ur, with attendants. Standard of Ur, c. 2600 BCE.

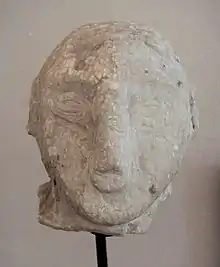

Sumerian princess of the time of Gudea circa 2150 BCE.

Sumerian princess of the time of Gudea circa 2150 BCE.

Scripts and languages

Similarities between Proto-Elamite (circa 3000 BCE) and especially Linear Elamite (2300-2000 BCE) scripts with the Indus script have been noted, although it has not been possible to decipher any of them.[126][127] Proto-Elamite only starts to be readable from around 2300 BCE, when Elamite adopted the cuneiform system.[126] These Elamite scripts are said to be "technically similar" to the Indus script.[126] On comparing the Linear Elamite to the Indus script, a number of similar symbols have also been found.[127]

The Meluhhan language was not readily understandable at the Akkadian court, since interpretators of the Meluhhan language are known to have resided in Mesopotamia, particularly through an Akkadian seal with the inscription "Shu-ilishu, interpreter of the Meluhhan language".[128][129][130]

.jpg.webp) Linear Elamite inscription the "Table of the Lion", time of king Kutik-Inshushinak, Louvre Museum Sb 17.

Linear Elamite inscription the "Table of the Lion", time of king Kutik-Inshushinak, Louvre Museum Sb 17. Transcription of the "Table of the Lion" Linear Elamite text.

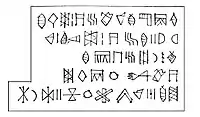

Transcription of the "Table of the Lion" Linear Elamite text. A seal with an inscription in the Indus script.

A seal with an inscription in the Indus script.

Chronology

Sargon of Akkad (circa 2300 or 2250 BCE), was the first Mesopotamian ruler to make an explicit reference to the region of Meluhha, which is generally understood as being the Baluchistan or the Indus area.[52] Sargon mentions the presence of Meluhha, Magan, and Dilmun ships at Akkad.[52]

These dates correspond roughly to the Mature Harappan phase, dated from around 2600 to 2000 BCE.[52] The dates for the main occupation of Mohenjo-Daro are from about 2350 to 2000/1900 BCE.[52]

It has been suggested that the early Mesopotamian Empire preceded the emergence of the Harappan civilization, and that trade and cultural exchanges may have facilitated the emergence of Harappan culture.[52] Alternatively, it is possible that the Harappan culture had already emerged by the time trade with Mesopotamia started.[52] Uncertainties in dating make it impossible to establish a clear order at this stage.[52]

Exchanges seem to have been most significant during the Akkadian Empire and Ur III periods, and to have waned afterwards together with the disappearance of the Indus valley civilization.[101]

Comparative sizes

The Indus Valley Civilization only flourished in its most developed form between 2500 and 1800 BCE until it became extinct, but at the time of these exchanges, it was a much larger entity than the Mesopotamian civilization, covering an area of 1.2 million square kilometres with thousands of settlements, compared to an area of only about 65,000 square kilometres for the occupied area of Mesopotamia, while the largest cities were comparable in size at about 30,000–40,000 inhabitants.[133]

There were altogether about 1,500 Indus valley cities, amounting to a population of perhaps 5 million at the maximum time of their florescence.[118] In contrast, the total urban population of Mesopotamia in 2,500 BCE was around 290,000.[134]

Large-scale exchanges recovered with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, circa 500 BCE.

Views of cultural diffusion

Many scholars have pointed towards exaggerated notions of cultural diffusions from Western Asia to the Indian subcontinent, such as when overlinking Vedic astronomy and mathematics to Sumerian origins.[135] Likewise scholars have questioned the supposed borrowings of Western Asian motifs without the evidence of any actual artifact and trade contacts.[136] Recent archaeogenetic research based on DNA samples collected from the Harappan site of Rakhigarhi suggests that Western Asian migration to northern India occurred as early as 12,000 years ago, but that the rise of agriculture in India was a later phenomenon, probably due to cultural exchanges around 2,000 years later, rather than direct migration.[137] According to Richard H. Meadow, evidence gathered from Mehrgarh points towards domestication of sheep, cattle and goats as a separate local phenomenon in the subcontinent around 7,000 BCE.[138][139]

See also

Notes

- According to Ahmad Hasan Dani, professor emeritus at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, the discovery of Mehrgarh "changed the entire concept of the Indus civilisation […] There we have the whole sequence, right from the beginning of settled village life."[14]

- Excavations at Bhirrana, Haryana, in India between 2006 and 2009, by archaeologist K.N. Dikshit, provided six artefacts, including "relatively advanced pottery," so-called Hakra ware, which were dated at a time bracket between 7380 and 6201 BCE.[17][18][19][20] These dates compete with Mehrgarh for being the oldest site for cultural remains in the area.[21]

Yet, Dikshit and Mani clarify that this time-bracket concerns only charcoal samples, which were radio-carbon dated at respectively 7570–7180 BCE (sample 2481) and 6689–6201 BCE (sample 2333).[22][23] Dikshit further writes that the earliest phase concerns 14 shallow dwelling-pits which "could accommodate about 3–4 people."[24] According to Dikshit, in the lowest level of these pits wheel-made Hakra Ware was found which was "not well finished,"[24] together with other wares.[25] - According to Gangal et al. (2014), there is strong archeological and geographical evidence that neolithic farming spread from the Near East into north-west India.[29][30] Gangal et al. (2014):[29] "There are several lines of evidence that support the idea of connection between the Neolithic in the Near East and in the Indian subcontinent. The prehistoric site of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan (modern Pakistan) is the earliest Neolithic site in the north-west Indian subcontinent, dated as early as 8500 BCE.[18][31]

Neolithic domesticated crops in Mehrgarh include more than 90% barley and a small amount of wheat. There is good evidence for the local domestication of barley and the zebu cattle at Mehrgarh [19],[32] [20],[33] but the wheat varieties are suggested to be of Near-Eastern origin, as the modern distribution of wild varieties of wheat is limited to Northern Levant and Southern Turkey [21].[34] A detailed satellite map study of a few archaeological sites in the Baluchistan and Khybar Pakhtunkhwa regions also suggests similarities in early phases of farming with sites in Western Asia [22].[35] Pottery prepared by sequential slab construction, circular fire pits filled with burnt pebbles, and large granaries are common to both Mehrgarh and many Mesopotamian sites [23].[36] The postures of the skeletal remains in graves at Mehrgarh bear strong resemblance to those at Ali Kosh in the Zagros Mountains of southern Iran [19].[32] Clay figurines found in Mehrgarh resemble those discovered at Teppe Zagheh on the Qazvin plain south of the Elburz range in Iran (the 7th millennium BCE) and Jeitun in Turkmenistan (the 6th millennium BCE) [24].[37] Strong arguments have been made for the Near-Eastern origin of some domesticated plants and herd animals at Jeitun in Turkmenistan (pp. 225–227 in [25]).[38]

The Near East is separated from the Indus Valley by the arid plateaus, ridges and deserts of Iran and Afghanistan, where rainfall agriculture is possible only in the foothills and cul-de-sac valleys [26].[39] Nevertheless, this area was not an insurmountable obstacle for the dispersal of the Neolithic. The route south of the Caspian sea is a part of the Silk Road, some sections of which were in use from at least 3,000 BCE, connecting Badakhshan (north-eastern Afghanistan and south-eastern Tajikistan) with Western Asia, Egypt and India [27].[40] Similarly, the section from Badakhshan to the Mesopotamian plains (the Great Khorasan Road) was apparently functioning by 4,000 BCE and numerous prehistoric sites are located along it, whose assemblages are dominated by the Cheshmeh-Ali (Tehran Plain) ceramic technology, forms and designs [26].[39] Striking similarities in figurines and pottery styles, and mud-brick shapes, between widely separated early Neolithic sites in the Zagros Mountains of north-western Iran (Jarmo and Sarab), the Deh Luran Plain in southwestern Iran (Tappeh Ali Kosh and Chogha Sefid), Susiana (Chogha Bonut and Chogha Mish), the Iranian Central Plateau (Tappeh-Sang-e Chakhmaq), and Turkmenistan (Jeitun) suggest a common incipient culture [28].[41] The Neolithic dispersal across South Asia plausibly involved migration of the population ([29][42] and [25], pp. 231–233).[38] This possibility is also supported by Y-chromosome and mtDNA analyses [30],[43] [31]."[44]

References

- Reade, Julian E. (2008). The Indus-Mesopotamia relationship reconsidered (Gs Elisabeth During Caspers). Archaeopress. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-4073-0312-3.

- "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum". Louvre Museum.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 187. ISBN 9781614510352.

- Robinson, Andrew (2015). The Indus: Lost Civilizations. Reaktion Books. p. 100. ISBN 9781780235417.

- Stiebing, William H. (2016). Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9781315511160.

- Burton, James H.; Price, T. Douglas; Kenoyer, J. Mark (2013). "A new approach to tracking connections between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia: initial results of strontium isotope analyses from Harappa and Ur". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (5): 2286–2297. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40.2286K. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.12.040. ISSN 0305-4403.

- "The wide distribution of lower Indus Valley seals and other artifacts from the Persian Gulf to Shortughaï in the Amu Darya/ Oxus River valley in Badakhshan (northeastern Afghanistan) demonstrates long-distance maritime and overland trade connections until ca. 1800 BCE." in Neelis, Jason (2011). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange within and beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Brill. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9789004194588.

- Demand, Nancy H. (2011). The Mediterranean Context of Early Greek History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 71–72. ISBN 9781444342345.

- Rowlands, Michael J. (1987). Centre and Periphery in the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780521251037.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Figure féminine - Les Musées Barbier-Mueller". www.musee-barbier-mueller.org.

- Tauger, Mark B. (2013). Agriculture in World History. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-136-94161-0.

- Chandler, Graham (September–October 1999). "Traders of the Plain". Saudi Aramco World: 34–42. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. ". Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh

- Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. "Mehrgarh". Guide to Archaeology

- "Archeologists confirm Indian civilization is 2000 years older than previously believed, Jason Overdorf, Globalpost, 28 November 2012".

- "Indus Valley 2,000 years older than thought". 2012-11-04. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015.

- "Archeologists confirm Indian civilization is 8000 years old, Jhimli Mukherjee Pandey, Times of India, 29 May 2016". The Times of India. 29 May 2016.

- "History What their lives reveal". 2013-01-04.

- "Haryana's Bhirrana oldest Harappan site, Rakhigarhi Asia's largest: ASI". The Times of India. 15 April 2015.

- Dikshit 2013, pp. 132, 131.

- Mani 2008, p. 237.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 129.

- Dikshit 2013, p. 130.

- "It has been virtual archaeological dogma for decades that Braidwood's constellation of potentially domesticable plants... were first domesticated in the Near East... early in the Holocene (c. 8,000 to 10,000 years ago). (...) The usual story is that domestic plants and animals, and the techniques of food production, then somehow "diffused" to other parts of the Old World, including South Asia." in Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. pp. 23–28. ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2.

- Jean-Francois Jarrige Mehrgarh Neolithic Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Paper presented in the International Seminar on the "First Farmers in Global Perspective," Lucknow, India, 18–20 January 2006

- Gangal, Sarson & Shukurov 2014.

- Singh 2016.

- Possehl GL (1999) Indus Age: The Beginnings. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press.

- Jarrige JF (2008) Mehrgarh Neolithic. Pragdhara 18: 136–154

- Costantini L (2008) The first farmers in Western Pakistan: the evidence of the Neolithic agropastoral settlement of Mehrgarh. Pragdhara 18: 167–178

- Fuller DQ (2006) Agricultural origins and frontiers in South Asia: a working synthesis. J World Prehistory 20: 1–86

- Petrie, CA; Thomas, KD (2012). "The topographic and environmental context of the earliest village sites in western South Asia". Antiquity. 86 (334): 1055–1067. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00048249. S2CID 131732322.

- Goring-Morris, AN; Belfer-Cohen, A (2011). "Neolithization processes in the Levant: the outer envelope". Curr Anthropol. 52: S195–S208. doi:10.1086/658860. S2CID 142928528.

- Jarrige C (2008) The figurines of the first farmers at Mehrgarh and their offshoots. Pragdhara 18: 155–166

- Harris DR (2010) Origins of Agriculture in Western Central Asia: An Environmental-Archaeological Study. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press.

- Hiebert FT, Dyson RH (2002) Prehistoric Nishapur and frontier between Central Asia and Iran. Iranica Antiqua XXXVII: 113–149

- Kuzmina EE, Mair VH (2008) The Prehistory of the Silk Road. Philadelphia: Univ. Pennsylvania Press

- Alizadeh A (2003) Excavations at the prehistoric mound of Chogha Bonut, Khuzestan, Iran. Technical report, University of Chicago, Illinois.

- Dolukhanov P (1994) Environment and Ethnicity in the Ancient Middle East. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Quintana-Murci, L; Krausz, C; Zerjal, T; Sayar, SH; Hammer, MF; et al. (2001). "Y-chromosome lineages trace diffusion of people and languages in Southwestern Asia". Am J Hum Genet. 68 (2): 537–542. doi:10.1086/318200. PMC 1235289. PMID 11133362.

- Quintana-Murci, L; Chaix, R; Spencer Wells, R; Behar, DM; Sayar, H; et al. (2004). "Where West meets East: the complex mtDNA landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian corridor". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (5): 827–845. doi:10.1086/383236. PMC 1181978. PMID 15077202.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 181. ISBN 9781576079072.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan M.; Heuston, Kimberley Burton (2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-522243-2.

The molded terra-cotta tablet shows a flat-bottomed Indus boat with a central cabin. Branches tied to the roof may have been used for protection from bad luck, and travelers took a pet bird along to help them guide them to land.

- Mathew 2017, p. 32.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 158-159. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Allchin, Raymond; Allchin, Bridget (29 July 1982). The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–189, listing of figures p.x. ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6.

- Mathew, K. S. (2017). Shipbuilding, Navigation and the Portuguese in Pre-modern India. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-351-58833-1.

- Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. Cornell University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0-8014-3339-9.

- Reade, Julian E. (2008). The Indus-Mesopotamia relationship reconsidered (Gs Elisabeth During Caspers). Archaeopress. pp. 14–17. ISBN 978-1-4073-0312-3.

- Drawings of Indus seals and inscriptions discovered in Ras al-Jinz, in Cleuziou, Serge; Gnoli, Gherardo; Robin, Christian Julien; Tosi, Maurizio (1994). "Cachets inscrits de la fin du IIIe millénaire av. notre ère à Ra's al-Junays, sultanat d'Oman (note d'information)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 138 (2): 453–468. doi:10.3406/crai.1994.15376.

- Frenez, Dennys (January 2018). "The Indus Civilization Trade with the Oman Peninsula". In the Shadow of the Ancestors. The Prehistoric Foundations of the Early Arabian Civilization in Oman – Second Expanded Edition (Cleuziou S. & M. Tosi): 385–396.

- British Museum notice: "Gold and carnelians beads. The two beads etched with patterns in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley. They were made by a technique developed by the Harappan civilization" Photograph of the necklace in question

- Gensheimer, T. R. (1984). "The Role of shell in Mesopotamia : evidence for trade exchange with Oman and the Indus Valley". Paléorient. 10: 71–72. doi:10.3406/paleo.1984.4350.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 182–190. ISBN 9781576079072.

- For the etching technique, see MacKay, Ernest (1925). "Sumerian Connexions with Ancient India". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (4): 699. JSTOR 25220818.

- Guimet, Musée (2016). Les Cités oubliées de l'Indus: Archéologie du Pakistan (in French). FeniXX réédition numérique. p. 355. ISBN 9782402052467.

- For a full list of discoveries of Indus seals in Mesopotamia, see Reade, Julian (2013). Indian Ocean In Antiquity. Routledge. pp. 148–152. ISBN 9781136155314.

- For another list of Mesopotamian finds of Indus seals: Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 221. ISBN 9780759101722.

- "Indus stamp-seal found in Ur BM 122187". British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 123208". British Museum.

"Indus stamp-seal discovered in Ur BM 120228". British Museum. - Gadd, G. J. (1958). Seals of Ancient Indian style found at Ur.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2012). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-971829-0.

- Joan Aruz; Ronald Wallenfels (2003). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

Square-shaped Indus seals of fired steatite have been found at a few sites in Mesopotamia.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2003). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780521011099.

- "The Indus Civilization and Dilmun, the Sumerian Paradise Land". www.penn.museum.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 425. ISBN 9788120611795.

- "Corpus by Asko Parpola". Mohenjodaro.

- Also, for another numbering scheme: Mahadevan, Iravatham (1987). The Indus Script. Text, Concordance And Tables Iravathan Mahadevan. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 32–36.

- MacKay, Ernest (1925). "Sumerian Connexions with Ancient India". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (4): 698–699. JSTOR 25220818.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 426. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781108173513.

- "Still the largest number of Indus or Indus-type finds is from Mesopotamia. Among the seals there are four indisputably Indus specimens: two from Kish (MacKay, 1925; Langdon, 1931) and one each from Lagash (Genouillac, 1930, p. 27) and Nippur (Gibson, 1977). The Nippur seal found in a 14th century ac Kassite context is in all probability a relic of an earlier period." in Allchin, Frank Raymond; Chakrabarti, Dilip K. (1997). A Source-book of Indian Archaeology: Settlements, technology and trade. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 560. ISBN 9788121504652.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. pp. 425–426. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Thureau-Dangint, F. (1925). "Sceaux de Tello et Sceaux de Harappa". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale. 22 (3): 99–101. JSTOR 23283916.

- Langdon, S. (1931). "A New Factor in the Problem of Sumerian Origins". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 63 (3): 593–596. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00110615. JSTOR 25194308. S2CID 163870671.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Guimet, Musée (2016). Les Cités oubliées de l'Indus: Archéologie du Pakistan (in French). FeniXX réédition numérique. pp. 354–355. ISBN 9782402052467.

- Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 395.

- Nandagopal, Prabhakar (2018-08-13). Decorated Carnelian Beads from the Indus Civilization Site of Dholavira (Great Rann of Kachchha, Gujarat). Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-78491-917-7.

- "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.

- Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. p. 398.

- "Indus carnelian bead found in Nippur Mesopotamia". www.metmuseum.org.

- Hall, Harry Reginald; Woolley, Leonard; Legrain, Leon (1934). Ur excavations. Trustees of the Two Museums by the aid of a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. p. 133.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. pp. 401–402. ISBN 9781588390431.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2014). "Tomb 197 at Abydos, further evidence for long distance trade in the Middle Kingdom". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 24: 159–170. doi:10.1553/s159. JSTOR 43553796.

- Stevenson, Alice (2015). Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology: Characters and Collections. UCL Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781910634042.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Cooper, Jerrol S. (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9780931464966.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 146. ISBN 9780759116429.

- Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (1975). An Introduction to the Study of Indian History. Popular Prakashan. p. 64. ISBN 9788171540389.

- Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology. Marshall Cavendish. p. 732. ISBN 9780761475651.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 389. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Singh. The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson Education India. p. 35. ISBN 9788131717530.

- "Possible influences from other cultures", citing Mesopotamian themes in Indus iconography Littleton, C. Scott (2005). Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology: Inca-Mercury. Marshall Cavendish. p. 732. ISBN 978-0-7614-7565-1.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7591-1642-9.

- Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (1975). An Introduction to the Study of Indian History. Popular Prakashan. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-7154-038-9.

- Reade, Julian E. (2008). The Indus-Mesopotamia relationship reconsidered (Gs Elisabeth During Caspers). Archaeopress. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-1-4073-0312-3.

- Josh, Jagat Pati (1987). Memoirs Of The Archeological Survey Of India No.86; Vol.1. p. 76.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 389. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Elisseeff, Vadime (2000). The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. Berghahn Books. p. 83. ISBN 9781571812223.

- Ameri, Marta; Costello, Sarah Kielt; Jamison, Gregg; Scott, Sarah Jarmer (2018). Seals and Sealing in the Ancient World: Case Studies from the Near East, Egypt, the Aegean, and South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108168694.

- Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 239–246.

- Dilip K. Chakrabarti (1990). The external trade of Indus civilization. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

The cylinder seals showing Indus influence in Mesopotamia (and also in Kalibangan) seem on the other hand to suggest that they were in response to the Indus-Mesopotamia overland trade.

- Mackay, Ernest John Henry; Langdon, Stephen; Laufer, Berthold (1925). Report on the excavation of the "A" cemetery at Kish, Mesopotamia. Chicago : Field Museum of Natural History.

- Mackay, Ernest John Henry; Langdon, Stephen; Laufer, Berthold (1925). Report on the excavation of the "A" cemetery at Kish, Mesopotamia. Chicago : Field Museum of Natural History. p. 61 Nb.3.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2010). Brotherhood of Kings: How International Relations Shaped the Ancient Near East. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9780199798759.

- ""An anthropomorphic figure has knelt in front of a fig tree, with hands raised in respectful salutation, prayer or worship. This reverence suggests the divinity of its object, another anthropomorphic figure standing inside the fig tree. In the ancient Near East, the gods and goddesses, as well as their earthly representatives, the divine kings and queens functioning as high priests and priestesses, were distinguished by a horned crown. A similar crown is worn by the two anthropomorphic figures in the fig deity seal. Among various tribal people of India, horned head-dresses are worn by priests on sacrificial occasions." in Conference, Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe International (1992). South Asian Archaeology, 1989: Papers from the Tenth International Conference of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, Musée National Des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, France, 3-7 July 1989. Prehistory Press. p. 227. ISBN 9781881094036.

- "Image of the seal with horned deity". www.columbia.edu.

- Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. ISBN 9781588390431.

- The Indus Script. Text, Concordance And Tables Iravathan Mahadevan. p. 139.

- Hall, Harry Reginald (1913). The ancient history of the Near East, from the earliest times to the battle of Salamis. London: Methuen & Co. pp. 173–174.

- Daniélou, Alain (2003). A Brief History of India. Simon and Schuster. p. 22. ISBN 9781594777943.

-

Material was adapted from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Płoszaj, Tomasz; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Jędrychowska-Dańska, Krystyna; Tomczyk, Jacek; Witas, Henryk W. (11 September 2013). "mtDNA from the Early Bronze Age to the Roman Period Suggests a Genetic Link between the Indian Subcontinent and Mesopotamian Cradle of Civilization". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e73682. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873682W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073682. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3770703. PMID 24040024.

Material was adapted from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License: Płoszaj, Tomasz; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Jędrychowska-Dańska, Krystyna; Tomczyk, Jacek; Witas, Henryk W. (11 September 2013). "mtDNA from the Early Bronze Age to the Roman Period Suggests a Genetic Link between the Indian Subcontinent and Mesopotamian Cradle of Civilization". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e73682. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...873682W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073682. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3770703. PMID 24040024. - "The 1,500 Harappan cities and towns contained a total population of perhaps 5 million people at their zenith" in Lockard, Craig A. (2014). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 39. ISBN 9781285783123.

- "The total urban population of Mesopotamia at 2500 B.C. had reached 290,000" Chew, Sing C. (2007). The Recurring Dark Ages: Ecological Stress, Climate Changes, and System Transformation. Rowman Altamira. p. 67. ISBN 9780759104525.

- Bradnock, Robert W. (2015). The Routledge Atlas of South Asian Affairs. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 9781317405115.

- Zhang, Ya-Ping; Chaudhuri, Tapas Kumar (9 October 2014). "Tamil Merchant in Ancient Mesopotamia". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e109331. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9331P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109331. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4192148. PMID 25299580.

- Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780521564960.

- Nigro, Lorenzo (1998). "The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq. 60: 85–102. doi:10.2307/4200454. hdl:11573/109737. JSTOR 4200454. S2CID 193050892.

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780190226930.

- "Meluhha interpreter seal. Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- "The so-called Proto-Elamite script from sites such as Susa in the lowlands of eastern Mesopotamia, dating from around 3000 BCE, is undeciphered and technically similar to the Harappan script." Ness, Immanuel (2014). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. p. 240. ISBN 9781118970584.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. p. 131. ISBN 9780759101722.

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780190226930.

- McIntosh, Jane (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: New Perspectives. ABC-CLIO. p. 279. ISBN 9781576079652.

- Robinson, Andrew (2015). The Indus: Lost Civilizations. Reaktion Books. p. 101. ISBN 9781780235417.

- Guimet, Musée (2016). Les Cités oubliées de l'Indus: Archéologie du Pakistan (in French). FeniXX réédition numérique. p. 354. ISBN 9782402052467.

- Mackay, Ernest (1935). Indus civilization. pp. Plate K, Item Nb 5.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2011). Asia: A Concise History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 42. ISBN 9780470829592.

- "However, the total urban population of Mesopotamia at 2500 B.C. had reached 290,000" Chew, Sing C. (2007). The Recurring Dark Ages: Ecological Stress, Climate Changes, and System Transformation. Rowman Altamira. p. 67. ISBN 9780759104525.

- Levitt, Stephen Hillyer (2012). "Vedicancient Mesopotamian Interconnections and the Dating of the Indian Tradition". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 93: 139. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 26491233.

- Kenoyer, Mark (2010). The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography: Master of Animals and Animal Masters in the Iconography of the Indus Tradition. Budapest. p. 53. ISBN 978-963-9911-14-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Price, Michael (2019-09-05). "Genome of nearly 5000-year-old woman links modern Indians to ancient civilization". Science. AAAS. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- Franke, Ute (January 2016). "Prehistoric Balochistan: Cultural Developments in an Arid Region". In Markus Reindel; Karin Bartl; Friedrich Lüth; Norbert Benecke (eds.). Palaeoenvironment and the Development of Early Settlements. ISBN 978-3-86757-395-5.

- Meadow, Richard H. (1991). Harappa Excavations 1986-1990 A Multidisciplinary Approach to Third Millennium Urbanism. Madison Wisconsin: Prehistory Press. pp. 94 Moving east to the Greater Indus Valley, decreases in the size of cattle, goat, and sheep also appear to have taken place starting in the 6th or even 7th Millennium BCE (Meadow 1984b, 1992). Details of that phenomenon, which I have argued elsewhere was a local process at least for sheep and cattle (Meadow 1984b, 1992).

Sources

- Dikshit, K.N. (2013), "Origin of Early Harappan Cultures in the Sarasvati Valley: Recent Archaeological Evidence and Radiometric Dates" (PDF), Journal of Indian Ocean Archaeology (9), archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-18

- Gadd, G. J. (1958). Seals of Ancient Indian style found at Ur.

- Mani, B.R. (2008), "Kashmir Neolithic and Early Harappan : A Linkage" (PDF), Pragdhara 18, 229–247 (2008), archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017, retrieved 17 January 2017

- Art of the first cities : the third millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bibliography

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015), The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE, Cambridge University Press

- Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

- Gallego Romero, Irene; et al. (2011), "Herders of Indian and European Cattle Share their Predominant Allele for Lactase Persistence", Mol. Biol. Evol., 29 (1): 249–260, doi:10.1093/molbev/msr190, PMID 21836184

- Gangal, Kavita; Sarson, Graeme R.; Shukurov, Anvar (2014), "The Near-Eastern roots of the Neolithic in South Asia", PLOS ONE, 9 (5): e95714, Bibcode:2014PLoSO...995714G, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095714, PMC 4012948, PMID 24806472

- Mascarenhas, Desmond D.; Raina, Anupuma; Aston, Christopher E.; Sanghera, Dharambir K. (2015), "Genetic and Cultural Reconstruction of the Migration of an Ancient Lineage", BioMed Research International, 2015: 1–16, doi:10.1155/2015/651415, PMC 4605215, PMID 26491681

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Anthony, David; Mallory, James; Reich, David (2018), The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia, bioRxiv 10.1101/292581, doi:10.1101/292581

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism. The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilisation, Oxford University Press

- Singh, Sakshi (2016), "Dissecting the influence of Neolithic demic diffusion on Indian Y-chromosome pool through J2-M172 haplogroup", Scientific Reports, 6: 19157, Bibcode:2016NatSR...619157S, doi:10.1038/srep19157, PMC 4709632, PMID 26754573

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)