Administrative divisions of the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty of China administered territory using a hierarchical system of three descending divisions: circuits (dào 道), prefectures (zhōu 州), and counties (xiàn 縣). Prefectures have been called jùn (郡) as well as zhōu (州) interchangeably throughout history, leading to cases of confusion, but in reality their political status was the same. The prefectures were furthered classified as either Upper Prefectures (shàngzhōu 上州), Middle Prefectures (zhōngzhōu 中州), or Lower Prefectures (xiàzhōu 下州) depending on population. An Upper Prefecture consisted of 40, 000 households and above, a Middle Prefecture 20, 000 households and above, and a Lower Prefecture anything below 20, 000 households. Some prefectures were further categorized as bulwark prefectures, grand prefectures, renowned prefectures, or key prefectures for strategic purposes. A superior prefecture was called a fu (府).

The scope and limits of each circuit's jurisdiction and authority differed greatly in practice, and often individual circuit inspectors' powers and autonomy grew to a point that the administrative system became popularly known as the "Three Divisions of Falsehood" (虛三級). As Tang territories expanded and contracted, edging closer to the period of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, administrative records of these divisions became poorer in quality, sometimes either missing or altogether nonexistent. Although the Tang administration ended with its fall, the circuit boundaries they set up survived to influence the Song dynasty under a different name: lù (路).

History

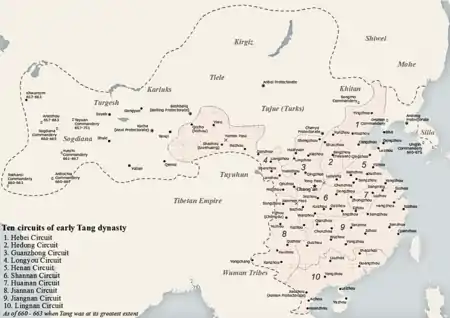

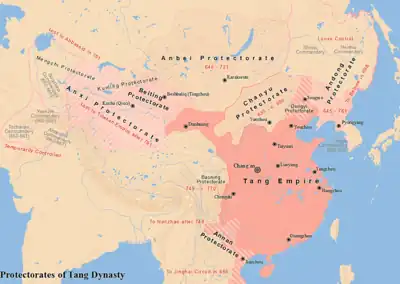

Emperor Taizong (r. 626−649) set up 10 "circuits" (道, dào) in 627 as areas for imperial commissioners to monitor the operation of prefectures, rather than as a direct level of administration. In the early Tang these geopolitical entities were not based on the realities of governance but rather ease of use when communicating which areas were to be monitored by the imperial commissioners. Prefects answered directly to the central government until the mid Tang dynasty when circuits took on new governmental responsibilities. In 639, there were 10 circuits, 43 commanderies (都督府, dūdū fǔ), and 358 prefectures (州 and later 府, fǔ).[1] In 733, Emperor Xuanzong expanded the number of circuits to 15 by establishing separate circuits for the areas around Chang'an and Luoyang, and by splitting the large Shannan and Jiangnan circuits into two and three new circuits respectively. He also established a system of permanent inspecting commissioners, though without executive powers.[2] In the year 740 CE, the administrative establishments of the Tang dynasty reached 15 circuits, 328 prefectures, and 1573 counties. Under the reforms of Emperors Zhongzong, Ruizong, and Xuanzong, these circuits became permanent administrative divisions. Circuits were assigned a number of permanent imperial commissioners of varying purposes and titles starting around the year 706 CE.

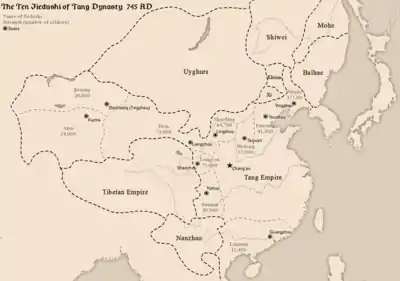

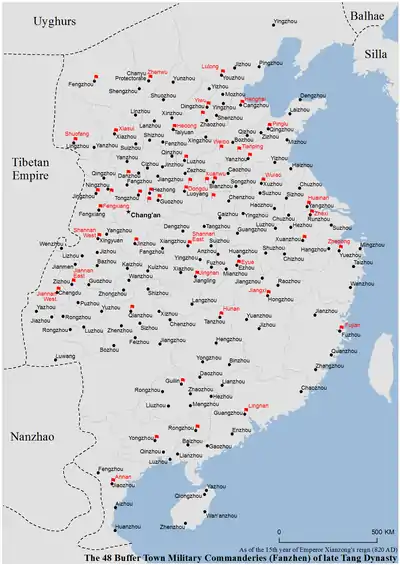

The Tang dynasty also created military districts (藩鎮 fānzhèn, meaning "buffer town") controlled by military commissioners known as jiedushi, charged with protecting frontier areas susceptible to foreign attack (similar to the European marches and marcher lords). Commanderies, (都督府, dūdū fǔ, literally "Office of the Commander-Governor"), which were border prefectures with a more powerful governor while prefecture (州, Zhōu) was the more common name for an inland secondary levels of administration. Dudu Fu was shortened to Fu, and the convention developed that larger prefectures would be named fu, while smaller prefectures would be called zhou. This system was eventually generalized to other parts of the country as well and essentially merged into the circuits. The greater autonomy and strength of the commissioners permitted insubordination and rebellion which led to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Administration

The correspondence of the Great Kings of China with the rulers of their provincial capitals and with their eunuch officials goes on post mules. These have their tails clipped in the manner of our post mules and follow recognized routes.[3]

— Abu Zayd al-Hasan al-Sirafi

The underlying principle of administration in the early Tang was to make administrative units so small that no locality could threaten or contest the dynasty's stability.

The primary level of administration was the prefecture, the zhōu (州), and had an average size of 25,650 households or 146,800 people.

The secondary level of administration was the district county, the xiàn (縣), and had an average population of roughly 30,000.

Officials assigned to these units were directly answerable to the imperial government and forbidden from amassing any personal armed forces. Officials were also restricted from serving in their native prefecture where clan ties and personal connections could jeopardize their loyalty to the court. To prevent officials from gaining personal power or local bonds the imperial government transferred them periodically to new localities. The same rules applied to the officials' immediate subordinates. The main purpose of these officials was to ensure taxes were sent to the central government, and in return the government sent back as much money as it deemed was appropriate for local needs. For these officials during most of the Tang era, posts outside the capital, even important ones, were treated as a form of exile.

Their landed property is not subject to a tax; instead, they themselves are taxed per capita of the male population. In the case of any Arab or other foreigner resident in the land, a tax is paid on his property in order to safeguard that property.[4]

— Abu Zayd al-Hasan al-Sirafi

Despite the transient role of these officials, there was a certain level of continuity within the local administration, imposed not by ambitious officials, but by petty subordinate officers who never rose above their regional stations. These men handled the majority of daily government affairs and were the indispensable repositories of local knowledge, usage, and administrative precedent that their superiors relied upon. As such the role they played cannot be exaggerated, for the customs of law and usage were considerably varied in Tang times. In numerous regions the magistrate could not even understand the speech of the people he administrated so he came to depend on his petty officers. Owing to the nature of their skills and knowledge, these posts tended to be hereditary, and office holders often became small but unique social groups. Although indispensable to the magistrates, it is unlikely that they represented the interests of their locality wholeheartedly or at all, since they too were dependent on the imperial government for prestige and power. Autonomy was not their primary concern.

More regional society could be found outside the walls of prefectural or districts towns among the powerful landowning clans of the countryside. Unlike petty officers, these clans formed an integral portion of rural society. Social networks included not just powerful clans but also small farmers, tenants, and tradesmen. Prefects, who typically employed a staff of only 57 men to administer 140,000 people, had to rely on the influence of these great clans to arbitrate disputes and preserve stability in the countryside. These clans represented a distinctively local interest, but were not necessarily ungenerous or hostile to centralized power, for the courts' officers served as protectors for their possessions and passed a large portion of the tax burden on to their poorer neighbors. In addition, the threat of imperial retribution was usually enough to keep such local magnates in line.

Military Regionalism

The king of India has many troops, but they are not paid as regular soldiers; instead, he summons them to fight for king and country, and they go to war at their own expense and at no cost at all to the king. In contrast, the Chinese give their troops regular pay, as the Arabs do.[5]

— Abu Zayd al-Hasan al-Sirafi

While the Tang government remained firmly in control this system worked as designed. However, in the years leading up to and following the An Lushan rebellion, changes in military organization enabled regional powers along the frontier to challenge the authority of the central government. To suppress the revolting powers, the government set up regional commands not only in border provinces but throughout the drainage basin of the Yellow River. By the year 785 the empire had divided into roughly forty provinces or dào (道) and their governors allotted wider powers over subordinate prefectures and districts. The province became another level of administration between the weakened central government and the prefectural and district authorities.

In the post-Ān Lùshān period, approximately 75% of all provincial governors were military men regardless of their titles and designations. Out of these, four of the most powerful military governors rebelled in Hebei. In return for their surrender, they were allowed to remain in command of their armies and to govern large tracts of land as they saw fit. In the year 775, Tian Chengsi of Weibo Jiedushi attacked and absorbed a large portion of Xiangzhou from Zhaoyi Jiedushi, resulting in the "three garrisons of Hebei": Youzhou (Yuzhou (modern Beijing)/Fanyang), Chengde (Rehe) ruled by Li Baochen, and Weibo. Although nominally subordinate to the Tang by accepting imperial titles, the garrisons governed their territories as independent fiefdoms with all the trappings of feudal society, establishing their own family dynasties through systematic intermarriage, collecting taxes, raising armies, and appointing their own officials. What's more, several of the leading military governors in Hebei were non-Chinese.

The Tang court sometimes tried to intervene when a governor died or was driven out by one of the frequent mutinies, however the most it achieved was in securing promises of larger shares in tax revenue in exchange for affirming the successor's position. In reality, not even these promises amounted to much, and the court was never able to extract a significant sum from the northeast. Between the period of time from 806 to 820 Emperor Xianzong defeated the independent military governors of Henan and for a short while extended imperial control into the north. Afterwards the Hebei armies acquiesced to court appointees, but these were soon driven out by mutinies.

The semi-autonomous nature of Hebei was not just a matter of elite politics at play, or else it would not have lasted so long, but was rather based on a fundamental and widely held separatist sentiment in the Hebei armies that had existed since the province's occupation by the Khitans dating back to the 690s. While the Tang court officials argued that the Khitans' success was partially due to local collaboration, accounts imply that bitter feelings of perceived betrayal by the Chang'an administration lingered for decades.

After military defeats suffered against the Tibetans in 790 resulting in the complete loss of the Anxi Protectorate, the northwestern provinces around Chang'an subsequently became the Tang's true frontier and was garrisoned personally by the court armies at all times. Military men came to fill governorship offices in these small provinces but owing to the small size of their holdings, provincial decline in productivity, and proximity to the capital, were unable to become autonomous like the provinces of Hebei. Deforestation in the region compounded the increasing soil erosion and desertification, which in turn reduced the amount of agricultural output in the area north and west of the capital. So by this time the armies, like Chang'an itself, depended on grain supplies shipped from the south. Despite their inability to provide self sustenance, they too showed independence in some aspects, and during the 9th century their office holders became a largely hereditary group.

In the Shandong peninsula the powerful Pinglu Jiedushi held power for several decades before the Tang court divided it into three smaller units in the 820s. However the domination of the peninsula by military regionalists persisted.

In Henan pacified rebels ruled as semi-autonomous governors for several decades after the rebellion. Thus Henan became a buffer zone situated between the court and the independent jiedushis occupying the north-east regions of Hebei and Shandong. Because Henan represented a crucial lifeline for the court due to the presence of the Grand Canal which Chang'an depended on for supplies, the Tang court stationed large garrisons in the area in an effort to keep the Henan jiedushis under control. These efforts were generally ineffective and the garrisons suffered repeated mutinies by their soldiers in the last decades of the eighth century. Only in the second decade of the 9th century did Xianzong restore effective administration to the region after a series of campaigns, but by then Henan had been depopulated by constant warfare and strife, so that it too came to rely on southern grain.

In a sense, these autonomous provinces operated in many ways like miniature replicas of the Tang realm, with their own finances, foreign policy, and bureaucratic recruitment and selection procedures. They were not, however, without attachments to the Tang court. Probably due to the fiercely competitive political environment, the governors of Youzhou, Chengde, and Weibo often depended on the legitimacy afforded by court sponsorship, something the ninth-century chief minister Li Deyu understood, "Although the armies in Hebei are powerful, their leaders cannot stand on their own; they depend on the orders of appointment from court to assuage their troops". The Hebei leaders saw themselves and the realms they ruled as similar polities to the great lords of the preimperial Warring States Period. Even during periods of open revolt against the state, like in late 782, the governors never denied the emperor's role, and instead proclaimed themselves "kings" - a title unambiguously lower in hierarchy to that of "emperor" in Chinese political thought. In these instances, the provincial bureaucracies temporarily converted into "feudal" courts and hierarchies, fully aware of the Warring States terminology which they employed.

Collapse of the Administration

Some 20 years after Emperor Wuzong's death, the Tang empire began its last phase of collapse. The source of the downfall can be traced to an event in 868 when a group of soldiers in Gui Prefecture (Guangxi) under Pang Xun rebelled after the government ordered them to extend their garrison duty for one extra year, even though they had already served six years on what was supposed to be a three-year assignment. The rebellion spread northwards to the Chang Jiang and Huai River before its suppression in 869 by Shatuo cavalry under the command of Li Guochang. While the Tang court was still smarting from the impact of the Pang Xun rebellion, in 874, a salt trader by the name of Wang Xianzhi stirred up another rebellion in Changyuan, Puzhou, Henan. In 875 Wang was joined by Huang Chao, who eventually took over leadership of the rebel army when Wang died in 878. The cataclysmic Huang Chao rebellion was one of such vast magnitude that it shook the very foundations of the Tang empire, destroying it both internally as well as cutting off any pre-existing foreign contacts it had with the outside world. At the rebellion's peak, Huang claimed to command an army of one million. It swept through much of the lower and middle Yangzi valleys, devastated the Central Plains, and went as far south as Guangzhou (879). After sacking the twin capitals Luoyang in 880 and Chang'an the following year, Huang Chao declared the founding of his Great Qí (大齊) dynasty.

Because of the events that occurred there, the trading voyages to China were abandoned and the country itself was ruined, leaving all traces of its greatness gone and everything in utter disarray... The reason for the deterioration of law and order in China, and for the end of the China trading voyages from Siraf, was an uprising led by a rebel from outside the ruling dynasty known as Huang Chao... In time... he marched on the great cities of China, among them Khanfu [Guangzhou]... At first the citizens of Khanfu held out against him, but he subjected them to a long siege... until, at last, he took the city and put its people to the sword.[6]

— Abu Zayd al-Hasan al-Sirafi

The court made slow progress in stamping out the rebellion due in large extent to the deterioration of central authority. The reigning sovereign Tang Xizong was subject to constant manipulation by eunuch officers like Tian Lingzi. Although the rebellion was finally defeated in 884, the court continued to face challenges posed by the warlords—officially military commissioners who held enormous regional power, including Li Maozhen in Fengxiang (Qizhou, Jingji 京畿), Li Keyong in Taiyuan (Bingzhou, Hedong), Wang Chongrong in Hezhong (Puzhou, Hedong), and Zhu Wen in Bianzhou, Henan. The country was constantly torn by the tug-of-war between the eunuchs and the warlords. The eunuchs used their physical control of the emperor as leverage to stay in power and carry out their agenda. The warlords wanted to purge the court of eunuch influence. Against this hopeless backdrop, the penultimate sovereign of Tang, Zhaozong, ascended the throne in 888, and although a man of lofty ambition, he remained throughout his reign a mere puppet in the machinations of court politics.

With the extermination of the court eunuchs in 903, the warlord Zhu Wen obtained absolute authority over the emperor. Since Zhu's core holdings were in Henan, he forced Zhaozong to move east to Luoyang in 904, where he was killed. The great city of Chang'an was abandoned and its structures dismantled for their building materials, never again attaining the strategic importance and prestige it presided over for the last millennium. Three years later in 907, the Tang empire officially came to a close when Zhu Wen dethroned its last sovereign.

Tang dynasty circuits

| Circuits of the Tang dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Capital | Approximate extent in terms of modern locations | ||

| Ancient name | Modern location | ||||||

| Duji* | 都畿 | 都畿 | Dūjī | Henan Fu | Luoyang | Luoyang and environs | |

| Guannei | 關內 | 关内 | Guānnèi | Jingzhao Fu | Xi'an | northern Shaanxi, central Inner Mongolia, Ningxia | |

| Hebei | 河北 | 河北 | Héběi | Weizhou | Wei County, Hebei | Hebei | |

| Hedong | 河東 | 河东 | Hédōng | Puzhou | Puzhou, Yongji, Shanxi | Shanxi | |

| Henan | 河南 | 河南 | Hénán | Bianzhou | Kaifeng | Henan, Shandong, northern Jiangsu, northern Anhui | |

| Huainan | 淮南 | 淮南 | Huáinán | Yangzhou | central Jiangsu, central Anhui | ||

| Jiannan | 劍南 | 剑南 | Jiànnán | Yizhou | Chengdu | central Sichuan, central Yunnan | |

| Jiangnan | 江南 | 江南 | Jiāngnán | Jiangnanxi + Jiangnandong (see map) | |||

| Qianzhong** | 黔中 | 黔中 | Qiánzhōng | Qianzhou | Pengshui | Guizhou, western Hunan | |

| Jiangnanxi** | 江南西 | 江南西 | Jiāngnánxī | Hongzhou | Nanchang | Jiangxi, Hunan, southern Anhui, southern Hubei | |

| Jiangnandong** | 江南東 | 江南东 | Jiāngnándōng | Suzhou | southern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shanghai | ||

| Jingji* | 京畿 | 京畿 | Jīngjī | Jingzhao Fu | Xi'an | Xi'an and environs ( modern Shaanxi) | |

| Lingnan | 嶺南 | 岭南 | Lǐngnán | Guangzhou | Guangdong, eastern Guangxi, northern Vietnam | ||

| Longyou | 隴右 | 陇右 | Lǒngyou | Shanzhou | Ledu County, Qinghai | Gansu | |

| Shannan | 山南 | 山南 | Shānnán | Shannanxi + Shannandong (see map) | |||

| Shannanxi** | 山南西 | 山南西 | Shānnánxī | Liangzhou | Hanzhong | southern Shanxi, eastern Sichuan, Chongqing | |

| Shannandong** | 山南東 | 山南东 | Shānnándōng | Xiangzhou | Xiangfan | southern Henan, Hubei | |

* Circuits established under Xuanzong, as opposed to Taizong's original ten circuits.

** Circuits established under Xuanzong by dividing Taizong's Jiangnan and Shannan circuits.

Other Tang-era circuits include the West Lingnan, Wu'an, and Qinhua circuits.

Protectorates

dūhùfǔ = DHF = 都護府 = Protectorate

dūdūfǔ = DDF = 都督府 = Commandery/Area Command

| Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Ānxīdūhùfǔ (安西都護府) | (640-648) Xīzhōu (西州) | Northwest of Turfan, Xinjiang. | post-640 | ca. 790 (conquered by Tǔbō/Tǔfān 吐蕃 (Tibetans)) |

| (648-651) Qiūcí (龜茲) | East of Kucha, Xinjiang. | |||

| (651-658) Xīzhōu (西州) | ||||

| (658-670) Qiūcí (龜茲) | ||||

| (670-693) Suìyè (碎葉) | Suyab, Kyrgyzstan. | |||

| (693-790) Qiūcí (龜茲) | ||||

| Anbei Protectorate (安北都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Ānběidūhùfǔ (安北都護府) | (687-) east of Tsetserleg | 669 (converted from Hànhǎi 瀚海 Protectorate

in Mongolia and South Siberia) |

757 (renamed Zhènběi (鎮北) | |

| (687-) Tóngchéng (同城) | Southeast of Ejin Banner, west Inner Mongolia | |||

| (687-) Xīānchéng (西安城) | Northwest of Minle and southeast of Zhangye, central Gansu | |||

| (698-) Yúnzhōng (雲中) | Northwest of Horinger, Inner Mongolia | |||

| (708-) Xīshòuxiángchéng (西受降城) | Northwest of Wuyuan | |||

| (714-) Zhōngshòuxiángchéng (中受降城) | Southwest of Baotou | |||

| (749-) Héngsàijūn (横塞軍) | Southwest of Urad Middle Banner | |||

| (755-757) Dàānjūn/Tiāndéjūn (大安軍/天德軍) | Northeast of Urad Front Banner | |||

| Andong Protectorate (安東都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Āndōngdūhùfǔ (安東都護府) | (668-) Pyongyang/Píngrǎng (平壤) | in Korea | 668 | 761 |

| (670-) Liáodōng Area | ||||

| (676-) Liáodōngchéng (遼東城) | Liaoyang, Liaoning | |||

| (677-) Xīnchéng (新城) | north of Fushun, Liaoning | |||

| (705-) Yōuzhōu (幽州) | in the southwest of Beijingshi | |||

| (714-) Píngzhōu (平州) | Lulong, Hebei | |||

| (743-761) old commandery seat of Liáoxī (遼西) | southeast of Yixian, Liaoning | |||

| Annan Protectorate (安南都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Ānnándúhùfǔ (安南都護府) | Sòngpíng (宋平) | Hanoi, Vietnam | 679 (converted from Jiaozhou 交州) | 757 (renamed Zhennan 鎮南)

766 (with frontier command installed) |

| Beiting Protectorate (北庭都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Běitíngdūhùfǔ (北庭都護府) | Tíngzhōu (庭州)/Beshbalik/Beiting | North of Jimsar | 702 | 790 (conquered by Tubo/Tufan Tibetans) |

| Chanyu Protectorate (單于都護府) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Seats | Modern Location | Created | Ended |

| Chányúdūhùfǔ (單于都護府) | Yúnzhōng (雲中) | Northwest of Horinger and south of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia | 664 (converted from Yunzhong Protectorate)

686 (renamed defense commissioner) 714-719, 720-843/845 (renamed Anbei) |

845 |

Circuits, Prefectures, and Counties

- Circuits (dao; 道) and Military Districts (fanzhen; 籓鎮)

- Prefectures (zhou; 州), Superior Prefectures (fu; 府) and Commanderies (dudufu; 都督府)

- Counties (xian; 縣)

Jingji

| Jingji Circuit (京畿道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Administrative Center for Prefectures | Counties | ||||||

| Jīngjīdào (京畿道) | Cháng'ān (長安) | ||||||||||

| Yōngzhōu (雍州) | Jīngzhàofǔ (京兆府) | Chángān (長安) | 20 | ||||||||

| Huázhōu (華州) | Xīngdéfǔ (興德府), Huáyīnjùn (華陰郡) | Zhèngxiàn (鄭縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Tóngzhōu (同州) | Píngyìjùn (馮翊郡) | Píngyìxiàn (馮翊郡) | 8 | ||||||||

| Shāngzhōu (商州) | Shàngluòjùn (上洛郡) | Shàngluòxiàn (上洛縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Qízhōu (岐州) | Fèngxiángfǔ (鳳翔府) | Yōngxiàn (雍縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Bīnzhōu (邠州) | Xīnpíngjùn (新平郡) | Xīnpíngxiàn (新平縣) | 4 | ||||||||

Duji

| Duji Circuit (都畿道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Dūjīdào (都畿道) | Dōngdū (東都/洛陽) | Dōngdū (東都/洛陽) | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| Luòzhōu (洛州) | Hénánfǔ (河南府) | Dōngdū (東都/洛陽) | 20 | ||||||||

| Rǔzhōu (汝州) | Línrǔjùn (臨汝郡) | Liángxiàn (梁縣) | 7 | ||||||||

Guannei

| Guannei Circuit (關內道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit (道) | Capital | Prefecture (州/府) | Other Names | Administrative Center for Prefectures | Counties (縣) | ||||||

| Guānnèidào (關內道) | Cháng'ān (長安) | Lǒngzhōu (隴州) | Qiānyángjùn (汧陽郡) | Qiānyuánxiàn (汧陽縣) | 3 | ||||||

| Jīngzhōu (涇州) | Bǎodìngjùn (保定郡) | Āndìngxiàn (安定縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yuánzhōu (原州) | Píngliángjùn (平涼州) | Pínggāoxiàn (平高縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Wèizhōu (渭州) | n/a | Xiāngwǔxiàn (襄武縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Wǔzhōu (武州) | Originally part of Yuánzhōu (原州) | Xiāoguānxiàn (蕭關縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Níngzhōu (甯州) | Péngyuánjùn (彭原郡) | Dìngānxiàn (定安縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qìngzhōu (慶州) | Shùnhuàjùn (順化郡) | Ānhuàxiàn (安化縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Fūzhōu (鄜州) | Luòjiāojùn (洛交郡) | Luòjiāoxiàn (洛交縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Fāngzhōu (坊州) | Zhōngbùjùn (中部郡) | Zhōngbùxiàn (中部縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dānzhōu (丹州) | Xiánníngjùn (咸寧郡) | Yìchuānxiàn (義川縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yánzhōu (延州) | Yánānjùn (延安郡) | Fūshīxiàn (膚施縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Língzhōu (靈州) | Lǐngwǔjùn (靈武郡) | Huílèxiàn (回樂縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Wēizhōu (威州) | Originally part of Língzhōu (靈州) | Míngshāxiàn (鳴沙縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Huìzhōu (會州) | Huìníngzhōu (會寧州) | Huìníngxiàn (會寧縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Yánzhōu (鹽州) | Wǔyuánjùn (五原州) | Wǔyuánxiàn (五原縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Xiàzhōu (夏州) | Shuòfāngjùn (朔方郡) | Shuòfāngxiàn (朔方縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Suízhōu (綏州) | Shàngjùn (上郡) | Shàngxiàn (上縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yínzhōu (銀州) | Yínchuānjùn (銀川郡) | Rúlínxiàn (儒林縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yòuzhōu (宥州) | Níngshuòjùn (寧朔郡) | Yánēnxiàn (延恩縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Línzhōu (麟州) | Xīnqínjùn (新秦郡) | Xīnqínxiàn (新秦縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Shèngzhōu (勝州) | Yúlínjùn (榆林郡) | Yúlínxiàn (榆林縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Fēngzhōu (豐州) | Jiǔyuánjùn (九原郡) | Jiǔyuánxiàn (九原縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Chányúdàdūhùfǔ (單于大都護府) | Yúnzhōngdūhùfǔ (雲中都護府) | n/a | 1 | ||||||||

| Ānběidàdūhùfǔ (安北大都護府) | Yānrándūhùfǔ (燕然都護府) | n/a | 2 | ||||||||

| Zhènběidàdūhùfǔ (鎮北大都護府) | n/a | n/a | 2 | ||||||||

Hedong

| Hedong Circuit (河東道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Hédōngdào (河東道) | Púzhōu (蒲州) | Púzhōu (蒲州) | Hézhōngfǔ (河中府) | Hédōngxiàn (河東縣) | 13 | ||||||

| Jìnzhōu(晉州) | Píngyángjùn (平陽郡) | Línfénxiàn (臨汾縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Jiàngzhōu(絳州) | Jiàngjùn (絳郡) | Zhèngpíngxiàn (正平縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Cízhōu(慈州) | Wénchéngjùn (文城郡) | Jíchāngxiàn (吉昌縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Xízhōu(隰州) | Dàníngjùn (大寧郡) | Xíchuānxiàn (隰川縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Bìngzhōu(并州) | Tàiyuánfǔ, Běidū, Tàiyuánjùn (太原府) (北都) (太原郡) | Jìnyángxiàn (晉陽縣) | 13 | ||||||||

| Fénzhōu(汾州) | Xīhéjùn (西河郡) | Xīhéxiàn, originally Xíchéng (西河縣) (隰城) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qìnzhōu(沁州) | Yángchéngjùn (陽城郡) | Qìnyuánxiàn (沁源縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Liáozhōu (遼州) | Lèpíngjùn (樂評郡) | Liáoshānxiàn (遼山縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Lánzhōu (嵐州) | Lóufánjùn (樓煩郡) | Yífāngxiàn (宜芳縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Xiànzhōu (憲州) | originally part of Lánzhōu (嵐州) | Lóufánxiàn (樓煩縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Shízhōu (石州) | Chānghuàjùn (昌化郡) | Líshíxiàn (離石縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Xīnzhōu (忻州) | Dìngxiāngjùn (定襄郡) | Xiùróngxiàn (秀容縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Dàizhōu (代州) | Yànménjùn (雁/鴈門郡) | Yànménxiàn (雁/鴈門縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yúnzhōu (雲州) | Yúnzhōngjùn (雲中郡) | Yúnzhōngxiàn (雲中縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Shuòzhōu (朔州) | Mǎyìjùn (馬邑郡) | Shànyángxiàn (善陽縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Yùzhōu (蔚州) | Xīngtángjùn (興唐郡) | Língqiūxiàn (靈丘縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Wǔzhōu (武州) | n/a | Wéndéxiàn (文德縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Xīnzhōu (新州) | n/a | Yǒngxīngxiàn (永興縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lùzhōu (潞州) | Shàngdǎngjùn (上黨郡) | Shàngdǎngxiàn (上黨縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Zézhōu (澤州) | Gāopíngjùn (高平郡) | Jìnchéngxiàn (晉城縣) | 6 | ||||||||

Henan

| Henan Circuit (河南道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Hénándào (河南道) | Biànzhōu (汴洲/開封) | Shǎnzhōu (陝州) | Shǎnjùn (陝郡) | Shǎnxiàn (陝縣) | 6 | ||||||

| Guózhōu (虢州) | Hóngnóngjùn (弘農郡) | Hóngnóngxiàn (弘農縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Huázhōu (滑州) | Língchāngjùn (靈昌郡) | Báimǎxiàn (白馬縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Zhèngzhōu (鄭州) | Xíngyángjùn (滎陽郡) | Guǎnchéngxiàn (管城縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Yǐngzhōu (潁州) | Rǔyīnjùn (汝陰郡) | Rǔyīnxiàn (汝陰縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Xǔzhōu (許州) | Yǐngchuānjùn (潁川郡) | Chángshèxiàn (長社縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Chénzhōu (陳州) | Huáiyángjùn (淮陽郡) | Wǎnqiūxiàn (宛丘縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Càizhōu (蔡州) | Rǔnánjùn (汝南郡) | Rǔyángxiàn (汝陽縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Biànzhōu (汴洲/開封) | Chénliújùn (陳留郡) | Jùnyíxiàn (俊儀縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Sòngzhōu (宋州) | Suīyángjùn (睢陽郡) | Sòngchéng (宋城) | 10 | ||||||||

| Bózhōu (亳州) | Qiáojùn (瞧郡) | Qiáoxiàn (瞧縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Xúzhōu (徐州) | Péngchéngjùn (彭城郡) | Péngchéngxiàn (彭城縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Sìzhōu (泗州) | Línhuáijùn (臨淮郡) | Línhuáixiàn (臨淮縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Háozhōu (濠州) | Zhōnglíjùn (鐘離郡) | Zhōnglíxiàn (中離縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Sùzhōu (宿州) | n/a | Fúlíxiàn (符離縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yùnzhōu (鄆州) | Dōngpíngjùn (東平郡) | Xūchāngxiàn (須昌縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Qízhōu (齊州) | Jǐnánjùn (濟南郡) | Lìchéngxiàn (歷城縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Cáozhōu (曹州) | Jìyīnjùn (濟陰郡) | Jìyīnxiàn (濟陰縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Púzhōu (濮州) | Púyángjùn (濮陽郡), Chángyuán (長垣) | Juànchéngxiàn (鄄城縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qīngzhōu (青州) | Běihǎijùn (北海郡) | Yìdūxiàn (益都縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Zīzhōu (淄州) | Zīchuānjùn (淄川郡) | Zīchuānxiàn (淄川縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dēngzhōu (登州) | Dōngmóujùn (東牟郡) | Péngláixiàn (蓬萊縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Láizhōu (萊州) | Dōngláijùn (東萊郡) | Yèxiàn (掖縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dìzhōu (棣州) | Lèānjùn (樂安郡) | Yàncìxiàn (厭次縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yǎnzhōu (兗州) | Lǔjùn (魯郡) | Xiáqiūxiàn (瑕丘縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Hǎizhōu (海州) | Dōnghǎijùn (東海州) | Qúshānxiàn (朐山縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yízhōu (沂州) | Lángxiéjùn (琅邪郡) | Línyíxiàn (臨沂縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Mìzhōu (密州) | Gāomìzhōu (高密郡) | Zhūchéngxiàn (諸城縣) | 4 | ||||||||

Hebei

| Hebei Circuit (河北道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Héběidào (河北道) | Wèizhōu (魏州) | Mèngzhōu (孟州) | originally part of Hénánfǔ (河南府) | Héyángxiàn (河陽縣) | 5 | ||||||

| Huáizhōu (懷州) | Hénèijùn (河內郡) | Hénèixiàn (河內縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Wèizhōu (魏州) | Wèijùn (魏郡) | Guìxiāngxiàn (貴鄉縣) | 14 | ||||||||

| Bózhōu (博州) | Bópíngjùn (博平郡) | Liáochéngxiàn (聊城縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Xiàngzhōu (相州) | Yèjùn (鄴郡) | Ānyángxiàn (安陽縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Wèizhōu (衛州) | Jíjùn (汲郡) | Jíxiàn (汲縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Bèizhōu (貝州) | Qīnghéjùn (清河郡) | Qīnghéxiàn (清河縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Chánzhōu (澶州) | originally part of Wèizhōu (魏州) | Dùnqiūxiàn (頓丘縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Xíngzhōu (邢州) | Jùlùjùn (鉅鹿郡) | Lónggāngxiàn (龍岡縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Míngzhōu (洺州) | Guǎngpíngjùn (廣平郡) | Yǒngniánxiàn (永年縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Huìzhōu (惠州) | originally part of Xiàngzhōu (相州), Míngzhōu (洺州) | Fǔyáng (滏陽) | 4 | ||||||||

| Zhènzhōu (鎮州) | Héngzhōu (恆州), Chángshānjùn (長山郡), Héngshānjùn (恆山郡) | Zhēndìngxiàn (真定縣) | 11 | ||||||||

| Jìzhōu (冀州) | Xìndūjùn (信都郡) | Xìndūjùn (信都縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Shēnzhōu (深州) | Ráoyángjùn (饒陽郡) | Lùzéxiàn (陸澤縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Zhàozhōu (趙州) | Zhàojùn (趙郡) | Píngjíxiàn (平棘縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Cāngzhōu (滄州) | Jǐngchéngjùn (景城郡) | Qīngchíxiàn (清池縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Jǐngzhōu (景州) | originally part of Cāngzhōu (滄州) | Gōnggāoxiàn (弓高縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dézhōu (德州) | Píngyuánjùn (平原郡) | Āndéxiàn (安德縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Dìngzhōu (定州) | Bólíngjùn (博陵郡) | Ānxǐxiàn (安喜縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Yìzhōu (易州) | Shànggǔjùn (上谷郡) | Yìxiàn (易縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Yōuzhōu (幽州) | Fànyángjùn (范陽郡) | Jìxiàn (薊縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Zhuōzhōu (涿州) | n/a | Fànyángxiàn (范陽縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yíngzhōu (瀛洲) | Héjiānjùn (河間郡) | Héjiānxiàn (河間縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Mòzhōu (莫州) | Wénānjùn (文安郡) | Mòxiàn (莫縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Píngzhōu (平州) | Běipíngjùn (北平郡) | Lúlóngxiàn (盧龍縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Guīzhōu (媯州) | Guīchuānjùn (媯川郡) | Huáiróngxiàn (懷戎縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Tánzhōu (檀州) | Mìyúnjùn (密雲郡) | Mìyúnxiàn (密雲縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Jìzhōu (薊州) | Yúyángjùn (漁陽郡) | Yúyángxiàn (漁陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yíngzhōu (營州) | Liǔchéngjùn (柳城郡) | Liǔchéngxiàn (柳城縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Āndōngdūhùfǔ (安東都護府) | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||||||

Shannandong (Shannan East)

| Shannandong Circuit (山南東道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Shānnándōngdào (山南東道) | Xiāngzhōu (襄州) | Jīngzhōu (荊州) | Jiānglíngfǔ (江陵府), Nándū (南都), Jiānglíngjùn (江陵郡) | Jiānglíngxiàn (江陵縣) | 8 | ||||||

| Xiázhōu (峽州) | Yílíngjùn (夷陵郡) | Yílíngxiàn (夷陵縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Guīzhōu (歸州) | Bādōngjùn (巴東郡) | Zǐguīxiàn (秭歸縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Kuízhōu (夔州) | Yūnānjùn (雲安郡) | Fèngjiéxiàn (奉節縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lǐzhōu (澧州) | Lǐyángjùn (澧陽郡) | Lǐyángxiàn (澧陽縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lǎngzhōu (朗州) | Wǔlíngzhōu (武陵郡) | Wǔlíngxiàn (武陵縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Zhōngzhōu (忠州) | Nánbīngjùn (南賓郡) | Línjiāngxiàn (臨江縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Fúzhōu (涪州) | Fúlíngjùn (涪陵郡) | Fúlíngxiàn (涪陵縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Wànzhōu (萬州) | Nánpǔjùn (南浦郡) | Nánpǔxiàn (南浦縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xiāngzhōu (襄州) | Xiāngyángjùn (襄陽郡) | Xiāngyángxiàn (襄陽縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Mìzhōu (泌州) | Tángzhōu (唐州), Huáiānjùn (淮安郡) | Mìyángxiàn (泌陽縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Suízhōu (隋州) | Hàndōngjùn (漢東郡) | Suíxiàn (隋縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dèngzhōu (鄧州) | Nányángjùn (南陽郡) | Rángxiàn (穰縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Jūnzhōu (均州) | Wǔdāngjùn (武當郡) | Wǔdāngxiàn (武當縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Fángzhōu (房州) | Fánglíngjùn (房陵郡) | Fánglíngxiàn (房陵縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Fùzhōu (復州) | Jìnglíngjùn (竟陵郡) | Miǎnyángxiàn (沔陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yǐngzhōu (郢州) | Fùshuǐjùn (富水郡) | Jīngshānxiàn (京山縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Jīnzhōu (金州) | Hànyīnjùn (漢陰郡) | Xīchéngxiàn (西城縣) | 6 | ||||||||

Shannanxi (Shannan West)

| Shannanxi Circuit (山南西道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Shānnánxīdào (山南西道) | Liángzhōu (梁州) | Liángzhōu (梁州) | Xīngyuánfǔ (興元府), Hànzhōngjùn (漢中郡), Hànchuānjùn (漢川郡) | Nánzhèngxiàn (南鄭縣) | 5 | ||||||

| Yángzhōu (洋州) | Yángchuānjùn (洋川郡) | Xīxiāngxiàn (西鄉縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lìzhōu (利州) | Yìchāngjùn (益昌郡) | Miángǔxiàn (綿谷縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Fèngzhōu (鳳州) | Héchíjùn (河池郡) | Liángquánxiàn (梁泉郡) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xīngzhōu (興州) | Shùnzhèngjùn (順政郡) | Shùnzhèngxiàn (順政縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Chéngzhōu (成州) | Tónggǔjùn (同谷郡) | Shànglùxiàn (上祿縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Wénzhōu (文州) | Yīnpíngjùn (陰平郡) | Qǔshuǐxiàn (曲水縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Fúzhōu (扶州) | Tóngchāngjùn (同昌郡) | Tóngchāngxiàn (同昌縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Jízhōu (集州) | Fúyángjùn (符陽郡) | Nánjiāngxiàn (難江縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Bìzhōu (壁州) | Shǐníngjùn (始寧郡) | Nuòshuǐxiàn (諾水縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Bāzhōu (巴州) | Qīnghùajùn (清化郡) | Huàchéngxiàn (化城縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Péngzhōu (蓬州) | Péngshānjùn (蓬山郡) | Dàyínxiàn (大寅縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Tōngzhōu (通州) | Tōngchuānjùn (通川郡) | Tōngchuānxiàn (通川縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Kāizhōu (開州) | Shèngshānjùn (盛山郡) | Shèngshānxiàn (盛山縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Lángzhōu (閬州) | Lángshānjùn (閬中郡) | lángshānxiàn (閬中縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Guǒzhōu (果州) | Nánchōngjùn (南充郡) | Nānchóngxiàn (南充縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qúzhōu (渠州) | Línshānjùn ((潾山郡)), Dàngqújùn (宕渠郡) | Liújiāngxiàn (流江縣) | 3 | ||||||||

Longyou

| Longyou Circuit (隴右道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Lǒngyòudào (隴右道) | Shànzhōu (鄯州) | Qínzhōu (秦州) | Tiānshuǐjùn (天水郡) | Chéngjìxiàn (成紀縣) | 6 | ||||||

| Hézhōu (河州) | Ānchāngjùn (安昌郡) | Fūhǎnxiàn (枹罕縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Wèizhōu (渭州) | Lǒngxījùn (隴西郡) | Xiāngwǔxiàn (襄武縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Shànzhōu (鄯州) | Xīpíngjùn (西平郡) | Huángshuǐxiàn (湟水縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Lánzhōu (蘭州) | Jīnchéngjùn (金城郡) | Jīnchéngxiàn (金城縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Línzhōu (臨州) | Dídàojùn (狄道郡),

originally part of Jīnchéngjùn (金城郡) |

Dídàoxiàn (狄道縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Jiēzhōu (階州) | originally Wǔzhōu (武郡), Wǔdūjùn (武都郡) | Jiānglìxiàn (將利縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Táozhōu (洮州) | Línzhōu (臨州), Líntáojùn (臨洮郡) | Líntánxiàn (臨潭縣) | 1 | ||||||||

| Mínzhōu (岷州) | Hézhèngjùn (和政郡) | Yìlèxiàn (溢樂縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Kuòzhōu (廓州) | Níngsàijùn (寧塞郡) | Guǎngwēixiàn (廣威縣), originally Huàlóng (化隆),

Huàchéng (化成) |

3 | ||||||||

| Diézhōu (疊州) | Héchuānjùn (合川郡) | Héchuānxiàn (合川縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Dàngzhōu (宕州) | Huáidàojùn (懷道郡) | Huáidàoxiàn (懷道縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Liángzhōu (涼州) | Wǔwēijùn (武威郡) | Gūzāngxiàn (姑臧縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Shāzhōu (沙州) | Dūnhuángjùn (敦煌郡) | Dūnhuángxiàn (敦煌縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Guāzhōu (瓜州) | Jìnchāngjùn (晉昌郡) | Jìnchāngxiàn (晉昌縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Gānzhōu (甘州) | Zhāngyèjùn (張掖郡) | Zhāngyèxiàn (張掖縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Sùzhōu (肅州) | Jiǔquánjùn (酒泉郡) | Jiǔquánxiàn (酒泉縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yīzhōu (伊州) | Yīwújùn (伊吾郡) | Yīwúxiàn (伊吾縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xīzhōu (西州) | Jiāohéjùn (交河郡) | Qiántíngxiàn (前庭縣), originally Gāochāng (高昌) | 5 | ||||||||

| Tíngzhōu (庭州) | Běitíngdàdūhùfǔ (北庭大都護府) | Jīnmǎnxiàn (金滿縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Ānxīdàdūhùfǔ (安西大都護府) | n/a | originally Xīzhōu (西州) | n/a | ||||||||

Huainan

| Huainan Circuit (淮南道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Huáinándào (淮南道) | Yángzhōu (揚州) | Yángzhōu (揚州) | Guǎnglíngjùn (廣陵郡) | Jiāngdūxiàn (江都縣) | 7 | ||||||

| Chǔzhōu (楚州) | Huáiyīnjùn (淮陰郡) | Shānyángxiàn (山陽縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Chúzhōu (滁州) | Yǒngyángjùn (永陽郡) | Qīngliúxiàn (清流縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Hézhōu (和州) | Lìyángjùn (歷陽郡) | Líyángxiàn (歷陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Shòuzhōu (壽州) | Shòuchūnjùn (壽春郡) | Shòuchūnxiàn (壽春縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Lúzhōu (廬州) | Lújiāngjùn (廬江郡) | Héféixiàn (合肥縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Shūzhōu (舒州) | Tóngānjùn (同安郡) | Huáiníngxiàn (懷寧縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Guāngzhōu (光州) | Yìyángjùn (弋陽郡) | Dìngchéngxiàn (定城縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qízhōu (蘄州) | Qíchūnjùn (蘄春郡) | Qíchūnxiàn (蘄春縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Ānzhōu (安州) | Ānlùjùn (安陸郡) | Ānlùxiàn (安陸縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Huángzhōu (黃州) | Qíānzhōu (齊安郡) | Huánggāngxiàn (黃岡縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Shēnzhōu (申州) | Yìyángjùn (義陽郡) | Yìyángxiàn (義陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

Jiangnandong (Jiangnan East)

| Jiangnandong Circuit (江南東道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Jiāngnándōngdào (江南東道) | Sūzhōu (蘇州) | Rùnzhōu (潤州) | Dānyángjùn (丹楊郡) | Dāntúxiàn (丹徒縣) | 4 | ||||||

| Shēngzhōu (昇州) | Jiāngníngjùn (江寧郡) | Shàngyuánxiàn (上元縣),

originally Jiāngníngxiàn (江寧縣) |

4 | ||||||||

| Chángzhōu (常州) | Jìnlíngjùn (晉陵郡) | Jìnlíngxiàn (晉陵縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Sūzhōu (蘇州) | Wújùn (吳郡) | Wúxiàn (吳縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Húzhōu (湖州) | Wúxingjùn (吳興郡) | Wūchéngxiàn (烏程縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Hángzhōu (杭州) | Yúhángjùn (餘杭郡) | Qiántángxiàn (錢塘縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Mùzhōu (睦州) | Xīndìngjùn (新定郡) | Jiàndéxiàn (建德縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Yuèzhōu (越州) | Huìjījùn (會稽郡) | Huìjīxiàn (會稽縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Míngzhōu (明州) | Yúyáojùn (餘姚郡) | Màoxiàn (鄮縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Qúzhōu (衢州) | Xìnānjùn (信安郡) | Xìnānxiàn (信安縣)/Xīānxiàn (西安縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Chǔzhōu (處州) | originally Kuòzhōu (括州), Jìnyúnjùn (縉雲郡),

Yǒngjiājùn (永嘉郡) |

Lìshuǐxiàn (麗水縣),

originally Kuòcāngxiàn (括蒼縣) |

6 | ||||||||

| Wùzhōu (婺州) | Dōngyángjùn (東陽郡) | Jīnhuáxiàn (金華縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Wēnzhōu (溫州) | originally part of Kuòzhōu (括州),

Yǒngjiājùn (永嘉郡) |

Yǒngjiāxiàn (永嘉縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Táizhōu (台州) | Línhǎijùn (臨海郡) | Línhǎixiàn (臨海縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Fúzhōu (福州) | Chánglèjùn (長樂郡) | Mǐnxiàn (閩縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Jiànzhōu (建州) | Jiānānjùn (建安郡) | Jiànānxiàn (建安縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Quánzhōu (泉州) | Qīngyuánjùn (清源郡) | Jìnjiāngxiàn (晉江縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Tīngzhōu (汀州) | Líntīngjùn (臨汀郡) | Chángtīngxiàn (長汀縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Zhāngzhōu (漳州) | Zhāngpǔjùn (漳浦郡) | Zhāngpǔxiàn (漳浦縣) | 3 | ||||||||

Jiangnanxi (Jiangnan West)

| Jiangnanxi Circuit (江南西道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Administrative Center of Prefectures | Counties | ||||||

| Jiānnánxīdào (江南西道) | Hóngzhōu (洪州) | Xuānzhōu (宣州) | Xuānchéngjùn (宣城郡) | Xuānchéngxiàn (宣城縣) | 8 | ||||||

| Shèzhōu (歙州) | Xīnānjùn (新安郡) | Shèxiàn (歙縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Chízhōu (池州) | originally part of Xuānzhōu (宣州) | Qiūpǔxiàn (秋浦縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Hóngzhōu (洪州) | Yùzhāngjùn (豫章郡) | Yùzhāngxiàn (豫章縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Jiāngzhōu (江州) | Xúnyángjùn (潯陽郡) | Xúnyángxiàn (潯陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Èzhōu (鄂州) | Jiāngxiàjùn (江夏郡) | Jiāngxiàxiàn (江夏縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Yuèzhōu (岳州) | Bālíngjùn (巴陵郡) | Bālíngxiàn (巴陵縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Ráozhōu (饒州) | Póyángjùn (鄱陽郡) | Póyángxiàn (鄱陽縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Qiánzhōu (虔州) | Nánkāngjùn (南康郡) | Gànxiàn (贛縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Jízhōu (吉州) | Lúlíngjùn (廬陵郡) | Lúlíngxiàn (廬陵縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yuánzhōu (袁州) | Yíchūnjùn (宜春郡) | Yíchūnxiàn (宜春縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xìnzhōu (信州) | originally part of Ráozhōu (饒州),

Qúzhōu (衢州) |

Yìyángxiàn (弋陽縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Fǔzhōu (撫州) | Línchuānjùn (臨川郡) | Línchuānxiàn (臨川縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Tánzhōu (潭州) | Chángshājùn (長沙郡) | Chángshāxiàn (長沙縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Héngzhōu (衡州) | Héngyángjùn (衡陽郡) | Héngyángxiàn (衡陽縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Yǒngzhōu (永州) | Línglíngjùn (零陵郡) | Línglíngxiàn (零陵縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dàozhōu (道州) | Jiānghuájùn (江華郡) | Yíngdàoxiàn (營道縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Chēnzhōu (郴州) | Guìyángzhōu (桂陽郡) | Chēnxiàn (郴縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Shàozhōu (邵州) | Shàoyángjùn (邵陽郡) | Shàoyángxiàn (邵陽縣) | 2 | ||||||||

Qianzhong

| Qianzhong Circuit (黔中道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Qiánzhōngdào (黔中道) | Qiánzhōu (黔州) | Qiánzhōu (黔州) | Qiánzhōngjùn (黔中郡) | Péngshuǐxiàn (彭水縣) | 6 | ||||||

| Chénzhōu (辰州) | Lúxījùn (盧溪郡) | Yuánlíngxiàn (沅陵縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Jǐnzhōu (錦州) | Lúyángjùn (盧陽郡) | Lúyángxiàn (盧陽縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Shīzhōu (施州) | Qīnghuàjùn (清化郡) | Qīngjiāngxiàn (清江縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Xùzhōu (敘州) | Tányángjùn (潭陽郡), Wūzhōu (巫州) | Lóngbiāoxiàn (龍標縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Jiǎngzhōu (獎州) | Lóngxījùn (龍溪郡) | Yèlángxiàn (夜郎縣), Éshānxiàn (峨山縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yízhōu (夷州) | Yìquánjùn (義泉郡) | Suíyángxiàn (綏陽縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Bōzhōu (播州) | Bōchuānjùn (播川郡) | Zūnyìxiàn (遵義縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Sīzhōu (思州) | Níngyíjùn (寧夷郡) | Wùchuānxiàn (務川縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Fèizhōu (費州) | Fúchuānjùn (涪川郡) | Fúchuānxiàn (涪川縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Nánzhōu (南州) | Nánchuānjùn (南川郡) | Nánchuānxiàn (南川縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Xīzhōu (溪州) | Língxījùn (靈溪郡) | Dàxiāngxiàn (大鄉縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Zhēnzhōu (溱州) | Zhēnxījùn (溱溪郡) | Róngyìxiàn (榮懿縣) | 5 | ||||||||

Jiannan

| Jiannan Circuit (劍南道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Jiànnándào (劍南道) | Yìzhōu (益州) | Yìzhōu (益州) | Chéngdūfǔ (成都府/蜀郡) | Shǔxiàn (蜀縣) | 10 | ||||||

| Péngzhōu (彭州) | Méngyángjùn (蒙陽郡) | Jiǔlǒngxiàn (九隴縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Shǔzhōu (蜀州) | Tángānjùn (唐安郡) | Jìnyuánxiàn (晉原縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Hànzhōu (漢州) | Déyángjùn (德陽郡) | Luòxiàn (雒縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Jiāzhōu (嘉州) | Qiánwèizhōu (犍為郡) | Lóngyóuxiàn (龍游縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Méizhōu (眉州) | Tōngyìjùn (通義郡) | Tōngyìxiàn (通義縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Qióngzhōu (邛州) | Línqióngjùn (臨邛郡) | Línqióngxiàn (臨邛縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Jiǎnzhōu (簡州) | Yángānjùn (陽安郡) | Yánganxiàn (陽安縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Zīzhōu (資州) | Zīyángjùn (資陽郡) | Pánshíxiàn (盤石縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Xīzhōu (巂州) | Yuèxījùn (越巂郡) | Yuèxījxiàn (越巂縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Yǎzhōu (雅州) | Lúshānjùn (盧山郡) | Yándàoxiàn (嚴道縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Lízhōu (黎州) | Hóngyuánjùn (洪源郡) | Hànyuánxiàn (漢源縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Màozhōu (茂州) | Tōnghuàjùn (通化郡) | Wènshānxiàn (汶山縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yìzhōu (翼州) | Línyìjùn (臨翼郡) | Wèishānxiàn (衛山縣),

originally Yìzhēn (翼針) |

3 | ||||||||

| Wéizhōu (維州) | Wéichuānjùn (維川郡) | Xuēchéngxiàn (薛城縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Róngzhōu (戎州) | Nánxījùn (南溪郡) | Bódàoxiàn (僰道縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Yáozhōu (姚州) | Yúnnánjùn (雲南郡) | Yáochéngxiàn (姚城縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Sōngzhōu (松州) | Jiāochuānjùn (交川郡) | Jiāchéngxiàn (嘉誠縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dāngzhòu (當州) | Jiāngyuánjùn (江源郡) | Tōngguǐxiàn (通軌縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xīzhōu (悉州) | Guīchéngjùn (歸誠郡) | Zuǒfēngxiàn (左封縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Jìngzhōu (靜州) | Jìngchuānxiàn (靜川郡) | Xītángxiàn (悉唐縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Zhèzhōu (柘州) | Péngshānjùn (蓬山郡) | Zhèxiàn (柘縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Gōngzhōu (恭州) | Gōnghuàjùn (恭化郡) | Héjíxiàn (和集縣),

originally Guǎngpíngxiàn (廣平縣) |

3 | ||||||||

| Bǎozhōu (保州) | Tiānbǎojùn (天保郡),

Fèngzhōu (奉州), Yúnshānjùn (雲山郡) |

Dìngliánxiàn (定廉縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Zhēnzhōu (真州) | Zhāodéjùn (昭德郡) | Zhēnfúxiàn (真符縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Bàzhōu (霸州) | Jìngróngjùn (靜戎郡) | n/a | 4 | ||||||||

| Qiánzhōu (乾州) | n/a | n/a | 2 | ||||||||

| Zǐzhōu (梓州) | Zǐtóngjùn (梓潼郡) | Qīxiàn (郪縣) | 9 | ||||||||

| Suìzhōu (遂州) | Suìníngjùn (遂寧郡) | Fāngyìxiàn (方義縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Miánzhōu (綿州) | Bāxījùn (巴西郡) | Bāxīxiàn (巴西縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Jiànzhōu (劍州) | Pǔānjùn (普安郡) | Pǔānxiàn (普安縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Hézhōu (合州) | Bāzhōngjùn (巴中郡) | Shíjìngxiàn (石鏡縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Lóngzhōu (龍州) | Yīnglíngjùn (應靈郡) | Jiāngyóuxiàn (江油縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Pǔzhōu (普州) | Ānyuèjùn (安岳郡) | Ānyuèxiàn (安岳縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Yúzhōu (渝州) | Nánpíngjùn (南平郡) | Bāxiàn (巴縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Língzhōu (陵州) | Rénshòujùn (仁壽郡) | Rénshòuxiàn (仁壽縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Róngzhōu (榮州) | Héyìjùn (和義郡) | Xùchuānxiàn (旭川縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Chāngzhōu (昌州) | n/a | Chāngyuánxiàn (昌元縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lúzhōu (瀘州) | Lúchuānjùn (瀘川郡) | Lúchuānxiàn (瀘川縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Bǎoníngdūhùfǔ (保寧都護府) | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||||||||

Lingnan

| Lingnan Circuit (嶺南道) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit | Capital | Prefecture | Other Names | Prefecture Capital | Counties | ||||||

| Lǐngnándào

(嶺南道) |

Guǎngzhōu

(廣州) |

Guìzhōu (桂州) | Shǐānjùn (始安郡) | Shǐānxiàn (始安縣) | 11 | ||||||

| Guǎngzhōu (廣州) | Nánhǎijùn (南海郡) | Nánhǎixiàn (南海縣) | 10 | ||||||||

| Dǎngzhōu (黨州) | Níngrénjùn (寧仁郡) | Shànláoxiàn (善勞縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Huánzhōu (環州) | Zhěngpíngjùn (整平郡) | Zhèngpíngxiàn (正平縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Jiāozhōu (交州) | Ānnánzhōngdūhùfǔ (安南中都護府),

formerly Jiāozhǐjùn (交趾郡) |

Sòngpíngxiàn (宋平縣) | 8 | ||||||||

| Gāngzhōu (岡州) | Xīnhuìjùn (新會郡) | Xīnhuìxiàn (新會縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Sháozhōu (韶州) | Shǐxīngjùn (始興郡) | Qǔjiāngxiàn (曲江縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Xúnzhōu (循州) | Hǎifēngjùn, Lóngchuānjùn

(海豐郡) (龍川郡) |

Guīshànxiàn (歸善縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Cháozhōu (潮州) | Cháoyángjùn (潮陽郡) | Hǎiyángxiàn (海陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Kāngzhōu (康州) | Jìnkāngjùn (晉康郡) | Duānxīxiàn (端溪縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Shuāngzhōu (瀧州) | Kāiyángjùn (開陽郡) | Shuāngshuǐxiàn (瀧水縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Duānzhou (端州) | Gāoyàojùn (高要郡) | Gāoyàoxiàn (高要縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Xīnzhōu (新州) | Xīnxīngjùn (新興郡) | Xīnxīngxiàn (新興縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Fēngzhōu (封州) | Línfēngjùn (臨封郡) | Fēngchuānxiàn (封川縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Pānzhōu (潘州) | Nánpānjùn (南潘郡) | Màomíngxiàn (茂名縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Chūnzhōu (春州) | Nánlíngjùn (南陵郡) | Yángchūnxiàn (陽春縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Qínzhōu (勤州) | Yúnfújùn (雲浮郡) | Fùlínxiàn (富林縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Luózhōu (羅州) | Zhāoyìjùn (招義郡) | Shíchéngxiàn (石城縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Biànzhōu (辯州) | Língshuǐjùn (陵水郡) | Shílóngxiàn (石龍縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Gāozhōu (高州) | Gāoliángjùn (高涼郡) | Liángdéxiàn (良德縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Ēnzhōu (恩州) | Ēnpíngjùn (恩平郡) | Qíānxiàn (齊安縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Léizhōu (雷州) | Hǎikāngjùn (海康郡) | Hǎikāngxiàn (海康縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yázhōu (崖州) | Zhūyájùn (珠崖郡) | Shěchéngxiàn (舍城縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Qióngzhōu (瓊州) | Qióngshānjùn (瓊山郡) | Qióngshānxiàn (瓊山縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Zhènzhōu (振州) | Yándéjùn (延德郡) | Níngyuǎnxiàn (寧遠縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Dānzhōu (儋州) | Chānghuàjùn (昌化郡) | Yìlúnxiàn (義倫縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Wànānzhōu (萬安州) | Wànānjùn (萬安郡) | Língshuǐxiàn (陵水縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yōngzhōu (邕州) | Lǎngníngjùn (朗寧郡) | Xuānhuàxiàn (宣化縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Chéngzhōu (澄州) | Hèshuǐjùn (賀水郡) | Shànglínxiàn (上林縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Bīnzhōu (賓州) | Lǐngfāngjùn (嶺方郡) | Lǐngfāngxiàn (嶺方縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Héngzhōu (橫州) | Níngpǔjùn (寧浦郡) | Níngpǔxiàn (寧浦縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Xúnzhōu (潯州) | Xúnjiāngjùn (潯江郡) | Guìpíngxiàn (桂平縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Luánzhōu (巒州) | Yǒngdìngjùn (永定郡), Chúnzhōu (淳州) | Yǒngdìngxiàn (永定縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Qīnzhōu (欽州) | Níngyuèjùn (寧越郡) | Qīnjiāngxiàn (欽江縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Guìzhōu (貴州) | Nándìngzhōu (南定州)

Nányǐnzhōu (南尹州) Yùlínjùn (鬱林郡) |

Yùlínxiàn (鬱林縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Gongzhōu (龔州) | Línjiāngjùn (臨江郡) | Píngnánxiàn (平南縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Xiàngzhōu (象州) | Xiàngjùn (象郡), Guìlínjùn (桂林郡) | Wǔhuàxiàn (武化縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Téngzhōu (藤州) | Gǎnyìjùn (感義郡) | Tánjīnxiàn (鐔津縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yánzhōu (岩州) | Chánglèjùn (常樂郡) | Chánglèxiàn (常樂縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yízhōu (宜州) | Lóngshuǐjùn (龍水郡) | Lóngshuǐxiàn (龍水縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Rángzhōu (瀼州) | Líntánjùn (臨潭郡) | Rángjiāngxiàn (瀼江縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Lóngzhōu (籠州) | Fúnánjùn (扶南郡) | Wǔqínxiàn (武勤縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Tiánzhōu (田州) | Héngshānjùn (橫山郡) | Héngshānxiàn (橫山縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Wúzhōu (梧州) | Cāngwújùn (蒼梧郡) | Cāngwúxiàn (蒼梧縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Hèzhōu (賀州) | Línhèjùn (臨賀郡) | Línhèxiàn (臨賀縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Liánzhōu (連州) | Liánshānjùn (連山郡) | Guìyángxiàn (桂陽縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Liǔzhōu (柳州) | Lóngchéngjùn (龍城郡) | Mǎpíngxiàn (馬平縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Fùzhōu (富州) | Kāijiāngjùn (開江郡) | Lóngpíngxiàn (龍平縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Zhāozhōu (昭州) | Pínglèjùn (平樂郡) | Pínglèxiàn (平樂縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Méngzhōu (蒙州) | Méngshānjùn (蒙山郡) | Lìshānxiàn (立山縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yánzhōu (嚴州) | Xúndéjùn (循德郡) | Láibīnxiàn (來賓縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Róngzhōu (融州) | Róngshuǐjùn (融水郡) | Róngshuǐxiàn (融水縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Sītángzhōu (思唐州) | Wǔlángjùn (武郎郡),

Jīmízhōu (羈縻州), Zhèngzhōu (正州) |

Wǔlángxiàn (武郎縣) | 2 | ||||||||

| Gǔzhōu (古州) | Lèxīngjùn (樂興郡) | Lèxīngxiàn (樂興縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Róngzhōu (容州) | Pǔníngjùn (普寧郡) | Běiliúxiàn (北流縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Láozhōu (牢州) | Dìngchuānjùn (定川郡) | Nánliúxiàn (南流縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Báizhōu (白州) | Nánchāngjùn (南昌郡) | Bóbáixiàn (博白縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Shùnzhōu (順州) | Shùnyìjùn (順義郡) | —— | 4 | ||||||||

| Xiùzhōu (繡州) | Chánglínjùn (常林郡) | Chánglínxiàn (常林縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Yùlínzhōu (鬱林州) | Yùlínjùn (鬱林郡) | Shínánxiàn (石南縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Dòuzhōu (竇州) | Huáidéjùn (懷德郡) | Xìnyìxiàn (信義縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yúzhōu (禺州) | Wēnshuǐjùn (溫水郡) | Éshíxiàn (峨石縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Liánzhōu (廉州) | Hépǔjùn (合浦郡) | Hépǔxiàn (合浦縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Yìzhōu (義州) | Liánchéngjùn (連城郡) | Lóngchéngxiàn (龍城縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Lùzhōu (陸州) | Yùshānjùn (玉山郡) | Wūléixiàn (烏雷縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Fēngzhōu (峰州) | Chénghuàjùn (承化郡) | Xīnchāngxiàn (新昌縣) | 5 | ||||||||

| Àizhōu (愛州) | Jiǔzhēnjùn (九真郡) | Jiǔzhēnxiàn (九真縣) | 6 | ||||||||

| Huānzhōu (驩州) | Rìnánjùn (日南郡) | Jiǔdéxiàn (九德縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Chángzhōu (長州) | Wényángjùn (文楊郡) | Wényángxiàn (文陽縣) | 4 | ||||||||

| Fúlùzhōu (福祿州) | Tánglínjùn (唐林郡) | Ānyuǎnxiàn (安遠縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Tāngzhōu (湯州) | Tāngquánjùn (湯泉郡) | Tāngquánxiàn (湯泉縣) | 3 | ||||||||

| Zhīzhōu (芝州) | Xīnchéngjùn (忻城郡) | Xīnchéngxiàn (忻城縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Wǔézhōu (武峨州) | Wǔéjùn (武峨郡) | Wǔéxiàn (武峨縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Yǎnzhōu (演州) | Lóngchíjùn (龍池郡), Zhōngyìjùn (忠義郡) | Zhōngyìxiàn (忠義縣) | 7 | ||||||||

| Wǔānzhōu (武安州) | Wǔqūjùn (武曲郡) | Wǔānxiàn (武安縣) | 2 | ||||||||

Footnotes

- Twitchett 1979, pp. 203, 205.

- Twitchett 1979, p. 404.

- Mackintosh-Smith 2014, p. 107.

- Mackintosh-Smith 2014, p. 49.

- Mackintosh-Smith 2014, p. 63.

- Mackintosh-Smith 2014, p. 67-68.

References

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, Otto Harrassowitz · Wiesbaden

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7.

- Guy, R. Kent (2010), Qing Governors and Their Provinces: The Evolution of Territorial Administration in China, 1644-1796, Seattle: University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295990187

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Perry, John C.; L. Smith, Bardwell (1976), Essays on T'ang Society: The Interplay of Social, Political and Economic Forces, Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-047611

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 978-957-32-0876-1

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2014), Two Arabic Travel Books, Library of Arabic Literature

- Twitchett, Dennis, ed. (1979). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906 AD, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U of M Center for Chinese Studies, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xu, Elina-Qian (2005), Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, Institute for Asian and African Studies 7

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7