Khajurgaon

Khajurgaon is a village in Lalganj block of Rae Bareli district, Uttar Pradesh, India.[2] It is located on the bank of the Ganges,[3] 12 km from Lalganj, the block and tehsil headquarters.[4] As of 2011, it has a population of 5,916 people, in 1,067 households.[2] It has 5 primary schools and 1 community health centre.[2] It serves as the headquarters of a nyaya panchayat which also includes 12 other villages.[5]

Khajurgaon

Khajurgāon | |

|---|---|

Village | |

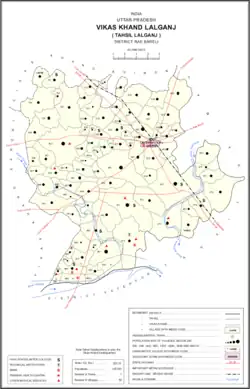

Map showing Khajurgaon Mu. (#861) in Lalganj CD block | |

Khajurgaon Location in Uttar Pradesh, India | |

| Coordinates: 26.071982°N 80.932433°E[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| District | Raebareli |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4.722 km2 (1.823 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • Total | 5,916 |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,200/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Hindi |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | UP-35 |

Khajurgaon historically served as the seat of a taluqdari estate belonging to a branch of the Saibasi Bais.[3] The estate was one of the largest in the district, and its holders claimed seniority over all the descendants of the legendary Bais raja Tilok Chand.[3]

Khajurgaon has a bazar known as Raghunathganj,[3] and it hosts both a permanent market and a weekly haat.[2] The haat is held twice per week, on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and it mostly involves trade in cloth and vegetables.[6]

History

Khajurgaon historically served as the fortified capital of the Ranas of Khajurgaon, who were historically one of the most powerful taluqdari dynasties in the district.[3] They were the leaders of the Saibasi clan of the Bais Rajputs, who claimed descent from the legendary Tilok Chand through his younger son Harhar Deo.[3] Later Saibasi dynasts, perhaps because of the ascendancy of Khajurgaon over the elder branch at Murarmau, would claim that they were in fact the senior branch of the entire Bais clan.[3] According to their account, Harhar Deo was actually the elder son of Tilok Chand, but he was away at Delhi when his father died and thus lost the title of Raja to his brother.[3] Upon his return, however, Harhar Deo was able to secure the greater share of the estate for himself, and he adopted the title of Rana for himself — a title which his descendants at Khajurgaon would continue to use through the 20th century.[3]

Harhar Deo's two sons, Khem Karan and Karan Rai, are respectively the ancestors of the Saibasi and Naihasta branches of the Bais.[3] Khem Karan's grandson, Rana Doman Deo, ruled from Chiloli and had eight sons, of whom the eldest was Ajit Mal, who became the Rana of Khajurgaon.[3] Ajit Mal's grandson, Rana Amar Singh, joined forces with the Naihasta clan under Chet Rai of Kurri Sudauli to recover their former lands in the parganas of Patan and Bihar.[3] Together they were able to defeat the rulers of Daundia Khera and Purwa, but they later had a falling out and Chet Rai left.[3] Amar Singh was then defeated in battle by Achal Singh of Purwa.[3] More disastrously, he was then defeated by Chhabile Ram of Allahabad in a battle near Dalmau sometime around 1710, and lost possession of his lands to the latter.[3]

Only after some 20 years had passed (i.e. around 1730) was Amar Singh's grandson, Pahar Singh, able to take possession of Khajurgaon again, along with three other villages.[3] Pahar Singh's reign was marked by constant fighting with his neighbours, and at one point the fort at Khajurgaon was seized by Chet Rai.[3] His descendants, however, became very powerful and by the time of the British takeover of Awadh in 1856 the Rana of Khajurgaon was the largest landowner in Baiswara.[3] This Rana was Raghunath Singh, who died in 1861 and was succeeded by his son Shankar Bakhsh Singh who then held the Khajurgaon estate until his death in 1897.[3]

At the turn of the 20th century, Khajurgaon was described as mostly notable as the headquarters of the taluqa of the same name.[3] It had the Rana's residence, a dispensary maintained by the estate, and a large primary school.[3] Its population as of 1901 was 2,638, including a Muslim minority of 183.[3] At that time, the Rana of Khajurgaon held a vast estate comprising 130 villages in the district, spread across the parganas of Dalmau, Rae Bareli, Khiron, and Sareni, along with the Ibrahimganj estate of 2 villages in Lucknow district and the Karohia property of 2 villages in Lakhimpur Kheri district.[3] In addition, the Rana also held a usufructuary mortgage over 97 villages in the Murarmau taluqa.[3]

The 1951 census recorded Khajurgaon (as "Khajur Gaon") as comprising 10 hamlets, with a total population of 2,751 people (1,333 male and 1,418 female), in 593 households and 579 physical houses.[7] The area of the village was given as 3,251 acres.[7] 14 residents were literate, all male.[7] The village was listed as belonging to the pargana of Dalmau and the thana of Dalmau.[7]

The 1961 census recorded Khajurgaon as comprising 10 hamlets, with a total population of 2,771 people (1,342 male and 1,429 female), in 560 households and 515 physical houses.[6] The area of the village was given as 2,251 acres and it had a hospital, medical practitioner, and post office at the time.[6] Average attendance of the twice-weekly market was about 100 people.[6]

The 1981 census recorded Khajurgaon as having a population of 3,803 people, in 772 households, and having an area of 490.49 hectares.[4] The main staple foods were listed as wheat and rice.[4]

The 1991 census recorded Khajurgaon Mu. as having a total population of 4,556 people (2,239 male and 2,317 female), in 783 households and 779 physical houses.[5] The area of the village was listed as 470 hectares.[5] Members of the 0-6 age group numbered 911, or 20% of the total; this group was 49% male (442) and 51% female (469).[5] Members of scheduled castes numbered 1,376, or 30% of the village's total population, while no members of scheduled tribes were recorded.[5] The literacy rate of the village was 32% (1,028 men and 438 women).[5] 1,154 people were classified as main workers (1,051 men and 103 women), while 63 people were classified as marginal workers (5 men and 58 women); the remaining 3,339 residents were non-workers.[5] The breakdown of main workers by employment category was as follows: 639 cultivators (i.e. people who owned or leased their own land); 272 agricultural labourers (i.e. people who worked someone else's land in return for payment); 0 workers in livestock, forestry, fishing, hunting, plantations, orchards, etc.; 0 in mining and quarrying; 36 household industry workers; 28 workers employed in other manufacturing, processing, service, and repair roles; 7 construction workers; 87 employed in trade and commerce; 14 employed in transport, storage, and communications; and 71 in other services.[5]

References

- "Geonames Search". Do a radial search using these coordinates here.

- "Census of India 2011: Uttar Pradesh District Census Handbook - Rae Bareli, Part A (Village and Town Directory)" (PDF). Census 2011 India. pp. 288–306. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Nevill, H.R. (1905). Rai Bareli: A Gazetteer, Being Volume XXXIX Of The District Gazetteers Of The United Provinces Of Agra And Oudh. Allahabad: Government Press. pp. 69, 71–3, 185. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Census 1981 Uttar Pradesh: District Census Handbook Part XIII-A: Village & Town Directory, District Rae Bareli (PDF). 1982. pp. 156–7. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- Census 1991 Series-25 Uttar Pradesh Part-XII B Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract District Census Handbook District Raebareli (PDF). 1992. pp. xxiv–xxviii, 196–7. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Census 1961: District Census Handbook, Uttar Pradesh (39 - Raebareli District) (PDF). Lucknow. 1965. pp. 175, lxxvi-lxxvii of section "Dalmau Tahsil". Retrieved 3 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Census of India, 1951: District Census Handbook Uttar Pradesh (42 - Rae Bareli District) (PDF). Allahabad. 1955. pp. 112–3. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)