Enlargement of NATO

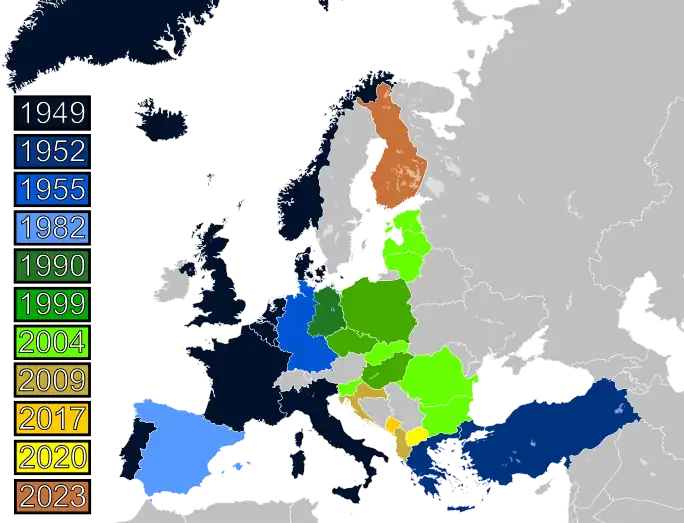

NATO is a military alliance of thirty-one European and North American countries that constitutes a system of collective defense. The process of joining the alliance is governed by Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which allows for the invitation of "other European States" only and by subsequent agreements. Countries wishing to join must meet certain requirements and complete a multi-step process involving political dialog and military integration. The accession process is overseen by the North Atlantic Council, NATO's governing body. NATO was formed in 1949 with twelve founding members and has added new members nine times. The first additions were Greece and Turkey in 1952. In May 1955, West Germany joined NATO, which was one of the conditions agreed to as part of the end of the country's occupation by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, prompting the Soviet Union to form its own collective security alliance (commonly called the Warsaw Pact) later that month. Following the end of the Franco regime, newly democratic Spain chose to join NATO in 1982.

In 1990, the negotiators reached an agreement that a reunified Germany would be in NATO under West Germany's existing membership. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, many former Warsaw Pact and post-Soviet states sought to join NATO. Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic became NATO members in 1999, amid much debate within NATO itself and Russian opposition. NATO then formalized the process of joining the organization with "Membership Action Plans", which aided the accession of seven Central and Eastern Europe countries shortly before the 2004 Istanbul summit: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Two countries on the Adriatic Sea—Albania and Croatia—joined on 1 April 2009 before the 2009 Strasbourg–Kehl summit. The next member states to join NATO were Montenegro on 5 June 2017, and North Macedonia on 27 March 2020.

Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 after Russia's president, Vladimir Putin, falsely claimed that NATO military infrastructure was being built up inside Ukraine and that Ukraine's potential future membership was a threat. Russia's invasion prompted Finland and Sweden to apply for NATO membership in May 2022.[1] Finland joined on 4 April 2023, while the ratification process for Sweden is ongoing.[2][3] Ukraine applied for NATO membership in September 2022 after Russia proclaimed the annexation of its territory.[1] Two other states have formally informed NATO of their membership aspirations: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Georgia.[4] Kosovo also aspires to join NATO.[5] Joining the alliance is a debate topic in several other European countries outside the alliance, including Austria, Cyprus, Ireland, Malta, Moldova, and Serbia.[6]

Past enlargements

Cold War

Twelve countries were part of NATO at the time of its founding: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The start of the Cold War between 1947 and 1953 saw an ideological and economic divide between the capitalist states of Western Europe backed by United States with its Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine, and the communist states of Eastern Europe, backed by the Soviet Union. As such, opposition to Soviet-style communism became a defining characteristic of the organization and the anti-communist governments of Greece, which had just fought a civil war against a pro-communist army, and Turkey, whose newly-elected Democrat Party were staunchly pro-American, came under internal and external pressure to join the alliance, which both did in February 1952.[7][8]

The US, France, and the UK initially agreed to end its occupation of Germany in May 1952 under the Bonn–Paris conventions on the condition that the new Federal Republic of Germany, commonly called West Germany, would join NATO, because of concerns about allowing a non-aligned West Germany to rearm. The allies also dismissed Soviet proposals of a neutral-but-united Germany as insincere.[9] France, however, delayed the start of the process, in part on the condition that a referendum be held in Saar on its future status, and a revised treaty was signed on 23 October 1954, allowing the North Atlantic Council to formally invite West Germany. Ratification of its membership was completed in May 1955.[10] That month the Soviet Union established its own collective defense alliance, commonly called the Warsaw Pact, in part as a response to West German membership in NATO.[11] In 1974, Greece suspended its NATO membership over the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, but rejoined in 1980 with Turkey's cooperation.[12]

Relations between NATO members and Spain under dictator Francisco Franco were strained for many years, in large part because Franco had cooperated with the Axis powers during World War II.[13] Though staunchly anti-communist, Franco reportedly feared in 1955 that a Spanish application for NATO membership might be vetoed by its members at the time.[14] Franco however did sign regular defense agreements with individual members, including the 1953 Pact of Madrid with the United States, which allowed use of its air and naval bases in Spain.[15][16] Following Franco's death in 1975, Spain began a transition to democracy, and came under international pressure to normalize relations with other western democracies. Prime Minister Adolfo Suárez, first elected in 1976, proceeded carefully on relations with NATO because of divisions in his coalition over the US's use of Spanish bases. In February 1981, following a failed coup attempt, Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo became Prime Minister and campaigned strongly for NATO membership, in part to improve civilian control over the military, and Spain's NATO membership was approved in June 1982.[16][17] A Spanish referendum in 1986 confirmed popular support for remaining in NATO.[18]

During the mid-1980s the strength and cohesion of the Warsaw Pact, which had served as the main institution rivaling NATO, began to deteriorate. By 1989 the Soviet Union was unable to stem the democratic and nationalist movements which were rapidly gaining ground. Poland held multiparty elections in June 1989 that ousted the Soviet allied Polish Workers' Party and the peaceful opening of the Berlin Wall that November symbolized the end of the Warsaw Pact as a way of enforcing Soviet control. The fall of the Berlin Wall is recognized to be the end of the Cold War and ushered in a new period for Europe and NATO enlargement.[19]

German reunification

Negotiations to reunite East and West Germany took place throughout 1990, resulting in the signing of the Two Plus Four Treaty in September 1990 and East Germany officially joining the Federal Republic of Germany on 3 October 1990. To secure Soviet approval of a united Germany remaining in NATO, the treaty prohibited foreign troops and nuclear weapons from being stationed in the former East Germany,[20] though an addendum signed by all parties specified that foreign NATO troops could be deployed east of the Cold War line after the Soviet departure at the discretion of the government of a united Germany.[21][22] There is no mention of NATO expansion into any other country in the September–October 1990 agreements on German reunification.[23] Whether or not representatives from NATO member states informally committed to not enlarge NATO into other parts of Eastern Europe during these and contemporary negotiations with Soviet counterparts has long been a matter of dispute among historians and international relations scholars.[24][25]

With several countries threatening to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, the Soviet military relinquished control of organization in March 1991, allowing it to be formally dissolved that July.[26][27] The so-called "parade of sovereignties" declared by republics in the Baltic and Caucasus regions of the Soviet Union and their War of Laws with the government in Moscow further fractured its cohesion. Following the failure of the New Union Treaty, the leadership of the remaining constituent republics of the Soviet Union, starting with Ukraine in August 1991, declared their independence and initiated the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which was completed in December of that year. Russia, led by President Boris Yeltsin, became the most prominent of the independent states.[28] The Westernization trend of many former Soviet allied states led them to privatize their economies and formalize their relationships with NATO countries, the first step for many towards European integration and possible NATO membership.[29][30]

.jpg.webp)

By August 1993, Polish President Lech Wałęsa was actively campaigning for his country to join NATO, at which time Yeltsin reportedly told him that Russia did not perceive its membership in NATO as a threat to his country. Yeltsin however retracted this informal declaration the following month,[31] writing that expansion "would violate the spirit of the treaty on the final settlement" which "precludes the option of expanding the NATO zone into the East."[32][33] During one of James Baker's 1990 talks with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Baker did suggest that the German reunification negotiations could have resulted in an agreement whereby "there would be no extension of NATO's jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east,"[34] and historians like Mark Kramer have interpreted it as applying, at least in the Soviets' understanding, to all of Eastern Europe.[35][36][25] Gorbachev later stated that NATO expansion was "not discussed at all" in 1990, but, like Yeltsin, described the expansion of NATO past East Germany as "a violation of the spirit of the statements and assurances made to us in 1990."[23][33][37]

This view, that informal assurances were given by diplomats from NATO members to the Soviet Union in 1990, is common in countries like Russia,[25][20] and, according to political scientist Marc Trachtenberg, available evidence suggests that allegations made since then by Russian leadership about the existence of such assurances "were by no means baseless."[24] Yeltsin was succeeded in 2000 by Vladimir Putin, who further promoted the idea that guarantees about enlargement were made in 1990, including during a 2007 speech in Munich.[38][37] This impression was later used by him as part of his justification for Russia's 2014 actions in Ukraine and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[39][23]

Visegrád Group

In February 1991, Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia formed the Visegrád Group to push for European integration under the European Union and NATO, as well as to conduct military reforms in line with NATO standards. Internal NATO reaction to these former Warsaw Pact countries was initially negative, but by the 1991 Rome summit in November, members agreed to a series of goals that could lead to accession, such as market and democratic liberalization, and that NATO should be a partner in these efforts. Debate within the American government as to whether enlargement of NATO was feasible or desirable began during the George H.W. Bush administration.[40] By mid-1992, a consensus emerged within the administration that NATO enlargement was a wise realpolitik measure to strengthen Euro-American hegemony.[40][41] In the absence of NATO enlargement, Bush administration officials worried that the European Union might fill the security vacuum in Central Europe, and thus challenge American post-Cold War influence.[40] There was further debate during the Presidency of Bill Clinton between a rapid offer of full membership to several select countries versus a slower, more limited membership to a wide range of states over a longer time span. Victory by the Republican Party, who advocated for aggressive expansion, in the 1994 US congressional election helped sway US policy in favor of wider full-membership enlargement, which the US ultimately pursued in the following years.[42] In 1996, Clinton called for former Warsaw Pact countries and post-Soviet republics to join NATO, and made NATO enlargement a part of his foreign policy.[43]

That year, Russian leaders like Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev indicated their country's opposition to NATO enlargement.[44] While Russian President Boris Yeltsin did sign an agreement with NATO in May 1997 that included text referring to new membership, he clearly described NATO expansion as "unacceptable" and a threat to Russian security in his December 1997 National Security Blueprint.[45] Russian military actions, including the First Chechen War, were among the factors driving Central and Eastern European countries, particularly those with memories of similar Soviet offensives, to push for NATO application and ensure their long-term security.[46][47] Political parties reluctant to move on NATO membership were voted out of office, including the Bulgarian Socialist Party in 1997 and Slovak HZDS in 1998.[48] Hungary's interest in joining was confirmed by a November 1997 referendum that returned 85.3% in favor of membership.[49] During this period, wider forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its eastern neighbors were set up, including the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (later the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council) and the Partnership for Peace.[50]

While the other Visegrád members were invited to join NATO at its 1997 Madrid summit, Slovakia was excluded based on what several members considered undemocratic actions by nationalist Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar.[51] Romania and Slovenia were both considered for invitation in 1997, and each had the backing of a prominent NATO member, France and Italy respectively, but support for this enlargement was not unanimous between members, nor within individual governments, including in the US Congress.[52] In an open letter to US President Bill Clinton, more than forty foreign policy experts including Bill Bradley, Sam Nunn, Gary Hart, Paul Nitze, and Robert McNamara expressed their concerns about NATO expansion as both expensive and unnecessary given the lack of an external threat from Russia at that time.[53] Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic officially joined NATO in March 1999.[54]

Vilnius Group

At the 1999 Washington summit NATO issued new guidelines for membership with individualized "Membership Action Plans" for Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia in order to standardize the process for new members.[55] In May 2000, these countries joined with Croatia to form the Vilnius Group in order to cooperate and lobby for common NATO membership, and by the 2002 Prague summit seven were invited for membership, which took place at the 2004 Istanbul summit.[56] Slovenia had held a referendum on NATO the previous year, with 66% approving of membership.[57]

Russia was particularly upset with the addition of the three Baltic states, the first countries that were part of the Soviet Union to join NATO.[58][56] Russian troops had been stationed in Baltic states as late as 1995,[59] but the goals of European integration and NATO membership were very attractive for the Baltic states.[60] Rapid investments in their own armed forces showed a seriousness in their desire for membership, and participation in NATO-led post-9/11 operations, particularly by Estonia in Afghanistan, won the three countries key support from individuals like US Senator John McCain, French President Jacques Chirac, and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.[59] A 2006 study in the journal Security Studies argued that the NATO enlargements in 1999 and 2004 contributed to democratic consolidation in Central and Eastern Europe.[61]

Adriatic Charter

Croatia also started a Membership Action Plan at the 2002 summit, but was not included in the 2004 enlargement. In May 2003, it joined with Albania and Macedonia to form the Adriatic Charter to support each other in their pursuit of membership.[62] Croatia's prospect of membership sparked a national debate on whether a referendum on NATO membership needed to be held before joining the organization. Croatian Prime Minister Ivo Sanader ultimately agreed in January 2008, as part of forming a coalition government with the HSS and HSLS parties, not to officially propose one.[63] Albania and Croatia were invited to join NATO at the 2008 Bucharest summit that April, though Slovenia threatened to hold up Croatian membership over their border dispute in the Bay of Piran.[64] Slovenia did ratify Croatia's accession protocol in February 2009,[65] before Croatia and Albania both officially joined NATO just before the 2009 Strasbourg–Kehl summit, with little opposition from Russia.[66]

Montenegro declared independence on 3 June 2006; the new country subsequently joined the Partnership for Peace program at the 2006 Riga summit and then applied for a Membership Action Plan on 5 November 2008,[67] which was granted in December 2009.[68] Montenegro also began full membership with the Adriatic Charter of NATO aspirants in May 2009.[69][70] NATO formally invited Montenegro to join the alliance on 2 December 2015,[71] with negotiations concluding in May 2016;[72] Montenegro joined NATO on 5 June 2017.[73]

.jpg.webp)

North Macedonia joined the Partnership for Peace in 1995, and commenced its Membership Action Plan in 1999, at the same time as Albania. At the 2008 Bucharest summit, Greece blocked a proposed invitation because it believed that its neighbor's constitutional name implies territorial aspirations toward its own region of Greek Macedonia. NATO nations agreed that the country would receive an invitation upon resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute.[74] Macedonia sued Greece at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) over Greece's veto of Macedonia's NATO membership. Macedonia was part of the Vilnius Group, and had formed the Adriatic Charter with Croatia and Albania in 2003 to better coordinate NATO accession.[75]

In June 2017, Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev signaled he would consider alternative names for the country in order to strike a compromise with Greece, settle the naming dispute and lift Greek objections to Macedonia joining the alliance. The naming dispute was resolved with the Prespa Agreement in June 2018 under which the country adopted the name North Macedonia, which was supported by a referendum in September 2018. NATO invited North Macedonia to begin membership talks on 11 July 2018;[76] formal accession talks began on 18 October 2018.[77] NATO's members signed North Macedonia's accession protocol on 6 February 2019.[78] Most countries ratified the accession treaty in 2019, with Spain ratifying its accession protocol in March 2020.[79] The Sobranie also ratified the treaty unanimously on 11 February 2020,[80] before North Macedonia became a NATO member state on 27 March 2020.[81][82]

Finland

.jpg.webp)

For much of the Cold War, Finland's relationship with NATO and the Soviet Union followed the Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine, whereby the country joined neither the Western nor Eastern blocs. Finland joined the Partnership for Peace in 1994, and provided peacekeeping forces to both NATO's Kosovo and Afghanistan missions in the early 2000s.[83]

Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, opinion polling for the first time showed a clear majority of Finns supported joining NATO.[84][85][86] On 15 May, Prime Minister Marin announced at a joint press conference with President Niinistö that Finland would apply for NATO membership.[87] On 17 May, the Parliament of Finland voted 188–8 in favor of joining NATO,[88] and a formal application was submitted for NATO membership on 18 May 2022.[89] On 1 March 2023, the Parliament of Finland approved Finland's accession to NATO by a vote of 184 in favor and 7 opposed.[90] Most countries approved Finland's application throughout 2022, but Hungary and Turkey held out over disputes until early 2023, with the Hungarian parliament approving the application on 27 March, and the Turkish parliament approved the application on 31 March 2023. Finland became a member of the alliance on 4 April 2023, the 74th anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty being signed.[91]

According to the Russian defence minister Sergei Shoigu, Finland's accession to NATO had significantly increased the risk of a wider conflict in Europe. Russia has 'threatened counter measure' by increasing the announced placement of nuclear weapons in Belarus. The move had doubled the length of the border that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization shares with Russia.[92][93] Putin however consistently dismissed Finland's and Sweden's accession to NATO[94] stating it poses "no threat to Russia".[95]

Summary Table and Map

| Date | Enlargement | Country |  | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

18 February 1952 |

First |

|||

9 May 1955 |

Second |

|||

30 May 1982 |

Third |

|||

3 October 1990 |

— |

|||

12 March 1999 |

Fourth |

|||

29 March 2004 |

Fifth |

|||

1 April 2009 |

Sixth |

|||

5 June 2017 |

Seventh |

|||

27 March 2020 |

Eighth |

|||

4 April 2023 |

Ninth |

|||

Criteria and process

Article 10 and the Open Door Policy

The North Atlantic Treaty is the basis of the organization, and, as such, any changes including new membership requires ratification by all current signers of the treaty. The treaty's Article 10 describes how non-member states may join NATO:

The Parties may, by unanimous agreement, invite any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area to accede to this Treaty. Any State so invited may become a Party to the Treaty by depositing its instrument of accession with the Government of the United States of America. The Government of the United States of America will inform each of the Parties of the deposit of each such instrument of accession.[96]

Article 10 poses two general limits to non-member states. First, only European states are eligible for new membership, and second, these states not only need the approval of all the existing member states, but every member state can put some criteria forward that have to be attained. In practice, NATO formulates a common set of criteria. However, for instance, Greece blocked the Republic of Macedonia's accession to NATO for many years because it disagreed with the use of the name Macedonia. Turkey similarly opposes the participation of the Republic of Cyprus with NATO institutions as long as the Cyprus dispute is not resolved.[97]

Since the 1991 Rome summit, when the delegations of its member states officially offered cooperation with Europe's newly democratic states, NATO has addressed and further defined the expectations and procedure for adding new members. The 1994 Brussels Declaration reaffirmed the principles in Article 10 and led to the "Study on NATO Enlargement". Published in September 1995, the study outlined the "how and why" of possible enlargement in Europe,[98] highlighting three principles from the 1949 treaty for members to have: "democracy, individual liberty, and rule of law".[99]

As NATO Secretary General Willy Claes noted, the 1995 study did not specify the "who or when,"[100] though it discussed how the then newly formed Partnership for Peace and North Atlantic Cooperation Council could assist in the enlargement process,[101] and noted that on-going territorial disputes could be an issue for whether a country was invited.[102] At the 1997 Madrid summit, the heads of state of NATO issued the "Madrid Declaration on Euro-Atlantic Security and Cooperation" which invited three Central European countries to join the alliance, out of the twelve that had at that point requested to join, laying out a path for others to follow.[98] The text of Article 10 was the origin for the April 1999 statement of a "NATO open door policy".[103]

Membership Action Plan

The biggest step in the formalization of the process for inviting new members came at the 1999 Washington summit when the Membership Action Plan (MAP) mechanism was approved as a stage for the current members to regularly review the formal applications of aspiring members. A country's participation in MAP entails the annual presentation of reports concerning its progress on five different measures:[104]

- Willingness to settle international, ethnic or external territorial disputes by peaceful means, commitment to the rule of law and human rights, and democratic control of armed forces

- Ability to contribute to the organization's defense and missions

- Devotion of sufficient resources to armed forces to be able to meet the commitments of membership

- Security of sensitive information, and safeguards ensuring it

- Compatibility of domestic legislation with NATO cooperation

NATO provides feedback as well as technical advice to each country and evaluates its progress on an individual basis.[105] Once members agree that a country meets the requirements, NATO can issue that country an invitation to begin accession talks.[106] The final accession process, once invited, involves five steps leading up to the signing of the accession protocols and the acceptance and ratification of those protocols by the governments of the current NATO members.[107]

In November 2002, NATO invited seven countries to join it via the MAP: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.[108] All seven invitees joined in March 2004, which was observed at a flag-raising ceremony on 2 April. After that date, NATO numbered 26 allies.[109] Other former MAP participants were Albania and Croatia between May 2002 and April 2009, Montenegro between December 2009 and June 2017, and North Macedonia between April 1999 and March 2020, when it joined NATO. As of 2022, there was only one country participating in a MAP, Bosnia and Herzegovina.[110]

Intensified dialogue

Intensified Dialogue was first introduced in April 2005 at an informal meeting of foreign ministers in Vilnius, Lithuania, as a response to Ukrainian aspirations for NATO membership and related reforms taking place under President Viktor Yushchenko, and which followed the 2002 signing of the NATO–Ukraine Action Plan under his predecessor, Leonid Kuchma.[105] This formula, which includes discussion of a "full range of political, military, financial and security issues relating to possible NATO membership ... had its roots in the 1997 Madrid summit", where the participants had agreed "to continue the Alliance's intensified dialogs with those nations that aspire to NATO membership or that otherwise wish to pursue a dialog with NATO on membership questions".[111]

In September 2006, Georgia became the second to be offered the Intensified Dialogue status, following a rapid change in foreign policy under President Mikhail Saakashvili[112] and what it perceived as a demonstration of military readiness during the 2006 Kodori crisis.[113] Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia similarly received offers at the April 2008 Bucharest summit.[114] While its neighbors both requested and accepted the dialog program, Serbia's offer was presented to guarantee the possibility of future ties with the alliance.[115]

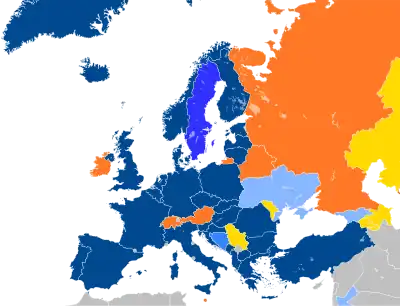

Current status

Accession protocol signed |

Enhanced Opportunity Partner |

As of 2023, four states have formally expressed their desire to join NATO. Bosnia and Herzegovina is the only country with a Membership Action Plan, which together with Georgia, were named NATO "aspirant countries" at the North Atlantic Council meeting on 7 December 2011.[116] Ukraine was recognized as an aspirant country after the 2014 Ukrainian revolution. In 2022, NATO signed protocols with Finland and Sweden on their accession following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Ukraine applied for membership in 2022. Finland joined NATO on 4 April 2023.

| Country[4] | Partnership for Peace[118] | Individualized Action Plan[119] | Intensified Dialogue | Membership Action Plan[120] | Application | Accession Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2006 | IPAP September 2008 | April 2008[122] | December 2018[123][Note 2] | |||

| March 1994 | IPAP October 2004 | September 2006[126] | ||||

| May 1994 | — | — | — | 18 May 2022[127] | 5 July 2022[3] (29/31 ratified[128]) | |

| February 1994 | Action Plan November 2002[Note 3] | April 2005[130] | —[Note 4] | 30 September 2022[132] |

- Membership Action Plan and Individual Partnership Action Plan countries are also Partnership for Peace members. States acceding to NATO replace Partnership for Peace membership with formal entry into the Alliance.

- Originally invited to join the MAP in April 2010 under the condition that no Annual National Programme would be launched until one of the conditions for the OHR closure – the transfer of control of immovable defence property to the central Bosnian authorities from the two regional political entities – was fulfilled.[124] Condition waived in 2018.

- NATO–Ukraine Action Plan adopted on 22 November 2002. Note that this is not considered by NATO to be an IPAP.[129]

- NATO agreed that a MAP would not be required.[131]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

.jpg.webp)

The 1995 NATO bombing of Bosnia and Herzegovina targeted the Bosnian Serb Army and together with international pressure led to the resolution of the Bosnian War and the signing of the Dayton Agreement in 1995. Since then, NATO has led the Implementation Force and Stabilization Force, and other peacekeeping efforts in the country. Bosnia and Herzegovina joined the Partnership for Peace in 2006, and signed an agreement on security cooperation in March 2007.[133] Bosnia and Herzegovina began further cooperation with NATO within its Individual Partnership Action Plan in January 2008.[121] The country then started the process of Intensified Dialogue at the 2008 Bucharest summit.[122] The country was invited to join the Adriatic Charter of NATO aspirants in September 2008.[134]

The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina within Bosnia and Herzegovina has expressed willingness to join NATO, however, it faces consistent political pressure from Republika Srpska, the other political entity in the country, alongside its partners in Russia. On 2 October 2009, Haris Silajdžić, the Bosniak Member of the Presidency, announced official application for Membership Action Plan. On 22 April 2010, NATO agreed to launch the Membership Action Plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina, but with certain conditions attached.[124] Turkey is thought to be the biggest supporter of Bosnian membership, and heavily influenced the decision.[135]

The conditions of the MAP, however, stipulated that no Annual National Programme could be launched until 63 military facilities are transferred from Bosnia's political divisions to the central government, which is one of the conditions for the OHR closure.[136][137] The leadership of the Republika Srpska has opposed this transfer as a loss of autonomy.[138] All movable property, including all weapons and other army equipment, is fully registered as the property of the country starting 1 January 2006.[139] A ruling of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 6 August 2017 decided that a disputed military facility in Han Pijesak is to be registered as property of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[140] Despite the fact that all immovable property is not fully registered, NATO approved the activation of the Membership Action Plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina, and called on Bosnia to submit an Annual National Programme on 5 December 2018.[123]

A February 2017 poll showed that 59% of the country supports NATO membership, but results were very divided depending on ethnic groups. While 84% of those who identified as Bosniak or Croat supported NATO membership, only 9% of those who identified as Serb did.[141] Bosnian chances of joining NATO may depend on Serbia's attitude towards the alliance, since the leadership of Republika Srpska might be reluctant to go against Serbian interests.[142] In October 2017, the National Assembly of the Republika Srpska passed a nonbinding resolution opposing NATO membership for Bosnia and Herzegovina.[143] On 2 March 2022, Vjosa Osmani, the President of Kosovo, called on NATO to speed up the membership process for Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Osmani also criticized Aleksandar Vučić, the President of Serbia, accusing him of using Milorad Dodik to "destroy the unity of Bosnia and Herzegovina".[144]

Sweden

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine led to Finland and Sweden applying for membership on 18 May 2022.[145] The move met opposition from Turkey, which called for the Nordic countries to lift their non-existent arms sales ban on Turkey and to stop any support for groups which Turkey and others have labeled as terrorists, including the Kurdish militant groups Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) (that Sweden banned in 1984) and Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) and Democratic Union Party (Syria) (PYD) and People's Defense Units (YPG), and of the followers of Fethullah Gülen, a US-based cleric accused by Turkey of orchestrating the failed 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt.[146][147] NATO leadership and the United States have said they were confident Turkey would not hold up the two countries' accession process. Additionally, Canadian Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly also held talks with Turkey to convince the Turkish government of the need for the two Nordic nations' integration.[148]

At the 2022 Madrid summit in June 2022, Turkey agreed to support the membership bids of Finland and Sweden,[149][150] leading to NATO immediately inviting both countries to join the organization without going through the Membership Action Plan process.[2] The ratification process for Sweden and Finland began on 5 July 2022.[3] As of 15 October 2022, all NATO member states except for Hungary and Turkey have approved the accession of the two countries and deposited their instruments of accession with the Government of the US.[151] On 1 February 2023, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced that he had a positive view of Finland's membership, and a negative view of Sweden's membership due to the Qur'an burning incidents in Sweden.[152]

.jpg.webp)

In 1949, Sweden chose not to join NATO and declared a security policy aiming for non-alignment in peace and neutrality in war.[153] A modified version now qualifies non-alignment in peace for possible neutrality in war. This position was maintained without much discussion during the Cold War. Since the 1990s, however, there has been an active debate in Sweden on the question of NATO membership in the post–Cold War era.[154] These ideological divides were visible in November 2006 when Sweden could either buy two new transport planes or join NATO's plane pool, and in December 2006, when Sweden was invited to join the NATO Response Force.[155][156] Sweden has been an active participant in NATO-led missions in Bosnia (IFOR and SFOR), Kosovo (KFOR), Afghanistan (ISAF), and Libya (Operation Unified Protector).[157]

Russia's military actions in Ukraine, first in 2014 and later in 2022, have caused most major political parties in Sweden to at least re-evaluate their positions on NATO membership, and many moved to support Swedish membership. The Centre Party, for example, was officially opposed to NATO membership until September 2015, when party leadership under Annie Lööf announced that it would move to change the party policy to push for Sweden to join NATO at its next party conference. The Christian Democrats likewise voted to support NATO membership at their October 2015 party meeting.[158] The center-right Moderate Party and center-left Liberal Party have both generally supported NATO membership since the end of the Cold War, with the Moderates even making it their top election pledge in 2022.[159][160] When the eurosceptic nationalist Sweden Democrats adjusted their stance in December 2020 to allow for NATO membership if coordinated with neighboring Finland, a majority of the members of the Swedish Riksdag for the first time belonged to parties that were open to NATO membership,[161] and a motion to allow for future NATO membership passed the parliament that month by 204 votes to 145.[162][163][164]

.jpg.webp)

Support for NATO membership over this period steadily increased, with polling by the SOM Institute showing it growing from 17% to 31% between 2012 and 2015.[165] Events like the annexation of Crimea and reports of Russian submarine activity in 2014, as well as a 2013 report that Sweden could hold out for only a week if attacked, were credited with that rise in support.[166] A May 2017 poll by Pew also showed that 48% supported membership, and in November 2020, it showed that 65% of Swedes viewed NATO positively, the highest percent of any non-NATO member polled.[167][168] A Novus poll conducted in late February 2022 found 41% in favor of NATO membership and 35% opposed.[169] On 4 March 2022, a poll was released that showed 51% support NATO membership, the first time a poll has shown a majority supporting this position.[170]

.jpg.webp)

The ruling Swedish Social Democratic Party, however, had remained in favor of neutrality and non-alignment for many years,[171] but following Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the party debated the issue internally in April 2022[172] and announced on 15 May 2022 that it would now support an application to join the organization.[173] Among its coalition partners, the Green Party remain opposed,[174] while the Left Party would like to hold a referendum on the subject, something Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson has rejected.[175] Andersson announced Sweden would indeed apply for NATO membership on 16 May 2022, in coordination with neighboring Finland,[176] and a formal application was submitted on 18 May 2022,[145] despite Russian threats of "military and political consequences."[177] As with neighboring Finland, the application was at least initially opposed by Turkey, which accused the two countries of supporting Kurdish groups PKK, PYD and YPG that Turkey views as terrorists,[178] and of the followers of Fethullah Gülen, whom Turkey was accused of orchestrating the alleged unsuccessful 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt.[179] On 20 May, Swedish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ann Linde pushed back against Erdoğan's claim they support PKK, calling it "disinformation", and pointing out Sweden listed PKK as a terrorist organization in 1984, while the EU followed suit in 2002.[180] Turkey later agreed, on 28 June 2022, to support Sweden's membership bid.[149][150] In January 2023 and in view of the continued Turkish refusal to agree to Swedish NATO membership Jimmie Åkesson of the Sweden Democrats reasoned that there were limits to how far Sweden would go to appease Turkey "because it is ultimately an anti-democratic system and a dictator we are dealing with".[181] Just prior a NATO summit in Vilnius in July 2023, Erdoğan linked Sweden's accession to NATO membership to Turkey's application for EU membership. Turkey had applied for EU membership in 1999, but talks made little progress since 2016.[182][183]

Georgia

Georgia moved quickly following the Rose Revolution in 2003 to seek closer ties with NATO[184] (although the previous administration had also indicated that it desired NATO membership a year before the revolution took place[185]). Georgia's northern neighbor, Russia, opposed the closer ties, including those expressed at the 2008 Bucharest summit, where NATO members promised that Georgia would eventually join the organization.[186] Complications in the relationship between NATO and Georgia includes the presence of Russian military forces in internationally recognized Georgian territory as a result of multiple recent conflicts, like the 2008 Russo-Georgian War over the territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both of which are home to a large number of citizens of Russia. On 21 November 2011, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev while addressing soldiers in Vladikavkaz near the Georgian border stated that Russia's 2008 invasion had prevented any further NATO enlargement into the former Soviet sphere.[186]

A nonbinding referendum in 2008 resulted in 77 percent of voters supporting NATO accession.[187] In May 2013, Georgian Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili stated that his goal was to get a Membership Action Plan (MAP) for his country from NATO in 2014.[188] In June 2014, diplomats from NATO suggested that while a MAP was unlikely, a package of "reinforced cooperation" agreements was a possible compromise.[189] Anders Fogh Rasmussen confirmed that this could include the building of military capabilities and armed forces training.[190]

In September 2019, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that "NATO approaching our borders is a threat to Russia."[191] He was quoted as saying that if NATO accepts Georgian membership with the article on collective defense covering only Tbilisi-administered territory (i.e., excluding the Georgian territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both of which are currently an unrecognized breakaway republics supported by Russia), "we will not start a war, but such conduct will undermine our relations with NATO and with countries who are eager to enter the alliance."[192]

On 29 September 2020, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg called on Georgia to use every opportunity to move closer to the Alliance and speed up preparations for membership. Stoltenberg stressed that earlier that year, the Allies agreed to further strengthen the NATO-Georgia partnership, and that NATO welcomed the progress made by Georgia in carrying out reforms, modernizing its armed forces and strengthening democracy.[193] Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili, who took office in 2018, has conceded that NATO membership might not be possible while Russia occupies Georgian territory, and has sought to focus on European Union membership,[194] which Georgia submitted its application for in May 2022.[195]

Ukraine

Ukraine's present and future relationship with NATO has been politically divisive, and is part of a larger debate over Ukraine's political and cultural ties to both the European Union and Russia. Ukraine established ties to the alliance with a NATO–Ukraine Action Plan in November 2002,[129][196] joined NATO's Partnership for Peace in February 2005,[197] then entered into the Intensified Dialogue program with NATO in April 2005.[198]

The position of Russian leaders on Ukraine-NATO relations has changed over time. In 2002, Russia's president Vladimir Putin declared no objections to Ukraine's growing relations with NATO and said it was a matter for Ukraine and NATO.[199] From 2008, Russia began stating its opposition to Ukraine's membership. That March, Ukraine applied for a Membership Action Plan (MAP), the first step in joining NATO. At the April 2008 Bucharest summit, NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer declared that Ukraine and Georgia would someday join NATO, but neither would begin Membership Action Plans.[200] At this summit, Putin called Ukrainian membership "a direct threat".[201]

When Viktor Yanukovych became Ukraine's president in 2010, he said that Ukraine would remain a "European, non-aligned state",[202][203] and would remain a member of NATO's outreach program.[204] In June 2010 the Ukrainian parliament voted to drop the goal of NATO membership in a bill drafted by Yanukovych.[205] The bill forbade Ukraine's membership in any military bloc, but allowed for co-operation with alliances such as NATO.[206]

The February 2014 Ukrainian Revolution brought another change in direction. Following months of protests that began because of his refusal to sign an Association Agreement with the EU in favor of deals from Russia, President Yanukovych fled to Russia, and Ukraine's parliament voted to remove him from his post. This was followed by pro-Russian unrest in eastern Ukraine, and Crimea was annexed by Russia. In March 2014, new Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk said Ukraine was not seeking NATO membership.[207]

However, because of Russian military intervention in Ukraine,[208] Yatsenyuk announced the resumption of the NATO membership bid,[209] and in December 2014, Ukraine's parliament voted to drop non-aligned status.[210] NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen said membership was still an option,[211] and support for membership rose to 64 percent in government-controlled Ukraine according to a July 2015 poll.[212] Polls had shown that the rise in support for membership was linked to Russia's ongoing military intervention.[213]

In June 2017, Ukraine's parliament passed a law making NATO integration a foreign policy priority,[214] and President Petro Poroshenko announced he would negotiate a Membership Action Plan.[215] Ukraine was acknowledged as an aspiring member by March 2018.[216] In September 2018, Ukraine's parliament approved amendments to the constitution, making NATO membership the main foreign policy goal.[217]

During 2021, there were massive Russian military build-ups near Ukraine's borders. In April 2021, Zelenskyy said that NATO membership "is the only way to end the war in Donbas" and that a MAP "will be a real signal for Russia".[218] Putin demanded that Ukraine be barred from ever joining NATO. Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg replied that Ukraine's relationship with NATO are a matter for Ukraine and NATO, adding that "Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbors".[219]

Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. In his speech announcing the invasion, Putin falsely claimed that NATO military infrastructure was being built up inside Ukraine, threatening Russia.[220] Russia's invasion drove Finland and Sweden to apply for NATO membership. In June 2022, Putin said their membership wasn't a problem for Russia, but Ukraine's membership is a "completely different thing" because of "territorial disputes".[221] However, after eight years of Russia denying any involvement in war in Donbas and denying any "territorial disputes" with Ukraine, this position has been interpreted as nothing but a pretext: Peter Dickinson from Atlantic Council wrote Putin dislike of NATO is likely genuine but not perceived as an actual threat to Russia. Instead, "Putin objects to NATO because it prevents him from bullying Russia’s neighbours".[94]

Since the invasion, calls for Ukrainian NATO membership have grown.[222] On 30 September 2022, Ukraine submitted an application for NATO membership.[132] According to Politico, NATO members are reluctant to discuss Ukraine's entry because of Putin's "hypersensitivity" on the issue.[223] At NATO's 2023 Vilnius summit it was decided that Ukraine would no longer be required to participate in a Membership Action Plan before joining the alliance.[131]

Membership debates

The Soviet Union was the primary ideological adversary for NATO during the Cold War. Following its dissolution, several states which had maintained neutrality during the Cold War or were post-Soviet states increased their ties with Western institutions; a number of them requested to join NATO. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine reignited debate surrounding NATO membership in several countries.

Austria, Ireland, Switzerland, and Malta have maintained their Cold War–era neutrality. All are now members of the Partnership for Peace, and all except Switzerland are now members of the European Union.[224] The defence ministry of Switzerland, which has a long-standing policy of neutrality, initiated a report in May 2022 analyzing various military options, including increased cooperation and joint military exercises with NATO. That month, a poll indicated 33% of Swiss supported NATO membership for Switzerland, and 56% supported increased ties with NATO.[225] Cyprus is also a member state of the European Union, but it is the only one that is neither a full member state nor participates in the Partnership for Peace. Any treaty concerning Cyprus' participation in NATO would likely be blocked by Turkey because of the Cyprus dispute.[226]

Russia, Armenia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan are all members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), a post-Soviet alternative military alliance. Azerbaijan was a member of the CSTO but has committed to a policy of neutrality since 1999.[227] In 2000, Russian President Vladimir Putin floated the idea of Russia potentially joining NATO.[228] However these prospects went nowhere and he began developing anti-NATO sentiment and espouses hostile views towards NATO today.[229] In 2009, Russian envoy Dmitry Rogozin did not rule out joining NATO at some point, but stated that Russia was currently more interested in leading a coalition as a great power.[230]

Austria

.jpg.webp)

Austria was occupied by the four victorious Allied powers following World War II under the Allied Control Council, similar to Germany. During negotiations to end of the occupation, which were ongoing at the same time as Germany's, the Soviet Union insisted that the reunified country adopt the model of Swiss neutrality. The US feared that this would encourage West Germany to accept similar Soviet proposals for neutrality as a condition for German reunification.[231] Shortly after West Germany's accession to NATO, the parties agreed to the Austrian State Treaty in May 1955, which was largely based on the Moscow Memorandum signed the previous month between Austria and the Soviet Union. While the treaty itself did not commit Austria to neutrality, this was subsequently enshrined into Austria's constitution that October with the Declaration of Neutrality. The Declaration prohibits Austria from joining a military alliance, from hosting foreign military bases within its borders, and from participating in a war.[232]

Membership of Austria in the European Union (or its predecessor organizations) was controversial because of the Austrian commitment to neutrality. Austria only joined in 1995, together with two Nordic countries that had also declared their neutrality in the Cold War (Sweden and Finland). Austria joined NATO's Partnership for Peace in 1995, and participates in NATO's Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. The Austrian military also participates in the United Nations peacekeeping operations and has deployments in several countries as of 2022, including Kosovo, Lebanon, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, where it has led the EUFOR mission there since 2009.[232] Several politicians from the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), including Andreas Khol, the 2016 presidential nominee, have argued in favor of NATO membership for Austria in light of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine,[233] and Chancellor from 2000 to 2007, Wolfgang Schüssel and his defense minister, Werner Fasslabend, both of the ÖVP, supported NATO membership as part of European integration during their tenure.[234] Current Chancellor Karl Nehammer, however, has rejected the idea of reopening Austria's neutrality and membership is not widely popular with the Austrian public.[235] According to a survey in May 2022 by the Austria Press Agency, only 14% of Austrians surveyed supported joining NATO, while 75% were opposed.[236]

Cyprus

Prior to gaining its independence in 1960, Cyprus was a crown colony of the United Kingdom and as such the UK's NATO membership also applied to British Cyprus. The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia in Cyprus remained under British control as a British Overseas Territory following independence.[237] Neighbouring Greece and Turkey competed for influence in the newly independent Cyprus, with intercommunal rivalries and movements for union with Greece or partition and partial union with Turkey. The first President of the independent Republic of Cyprus (1960–1977), Archbishop of Cyprus Makarios III, adopted a policy of non-alignment and took part in the 1961 founding meeting of the Non-Aligned Movement in Belgrade.

The 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus and ongoing dispute, in which Turkey continues to occupy Northern Cyprus, complicates Cyprus' relations with NATO. Any treaty concerning Cyprus' participation in NATO, either as a full member, PfP or Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, would likely be vetoed by Turkey, a full member of NATO, until the dispute is resolved.[226] NATO membership for a reunified Cyprus has been proposed as a solution to the question of security guarantees, given that all three of the current guarantors under the Treaty of Guarantee (1960) (Greece, Turkey and the United Kingdom) are already NATO members.[238]

The Parliament of Cyprus voted in February 2011 to apply for membership in the PfP program, but President Demetris Christofias vetoed the decision as it would hamper his attempts to negotiate an end to the Cyprus dispute and demilitarize the island.[239][240] The winner of Cyprus' presidential election in February 2013, Nicos Anastasiades, stated that he intended to apply for membership in the PfP program soon after taking over.[241] His foreign minister and successor Nicos Christodoulides dismissed Cypriot membership of NATO or Partnership for Peace, preferring to keep Cyprus' foreign and defence affairs within the framework of the European Union.[242] In May 2022, Cyprus Defence Minister, Charalambos Petrides, confirmed that the country would not apply to NATO despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[243]

Ireland

Ireland was neutral during World War II, though the country cooperated with Allied intelligence and permitted the Allies use of Irish airways and ports. Ireland continued its policy of military neutrality during the Cold War, and after it ended, joined NATO's Partnership for Peace (PfP) program and Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) in 1999.[245] Ireland participates in the alliance's PfP Planning and Review Process (PARP), which aims to increase the interoperability of the Irish military, the Defence Forces, with NATO member states and bring them into line with accepted international standards so as to successfully deploy with other professional military forces on peacekeeping operations overseas.[246] Ireland supplied a small number of troops to the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan (2001–2014) and supports the ongoing NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR).[247][248] Former Secretary General of NATO Anders Fogh Rasmussen said during a visit to the country in 2013 that the "door is open" for Ireland to join NATO at any time.[249]

There are a number of politicians who do support Ireland joining NATO, mainly within the center-right Fine Gael party, but the majority of politicians still do not.[250][251] The republican party Sinn Féin proposed a constitutional amendment to prohibit the country from joining a military alliance like NATO, but the legislation failed to pass the Dáil Éireann in April 2019.[252][253] While Taoiseach Micheál Martin said in 2022 that Ireland would not need to hold a referendum in order to join NATO, Irish constitutional lawyers have pointed to the precedent set by the 1987 case Crotty v. An Taoiseach as suggesting it would be necessary, and that any attempt to join NATO without a referendum would likely be legally challenged in the country's courts in a similar way.[254] Currently no major political party in Ireland fully supports accession to NATO, a reflection on public and media opinion in the country.[255] A poll in early March 2022 found 37% in favor of joining NATO and 52% opposed,[256] while one at the end of March 2022, found a sharp rise of approval with 48% supporting NATO membership and 39% opposing it.[257] An August 2022 poll found 52% in favor of joining and 48% opposed,[258] while a June 2023 poll found 34% in favour and 38% opposed.[259]

Kosovo

According to Minister of Foreign Affairs Enver Hoxhaj, integration with NATO is a priority for Kosovo, which declared independence from Serbia in 2008.[260] Kosovo submitted an application to join the PfP program in July 2012,[261] and Hoxhaj stated in 2014 that the country's goal is to be a NATO member by 2022.[262] In December 2018, Kosovar Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj stated that Kosovo will apply for NATO membership after the formation of the Kosovo Armed Forces.[263] Kosovo's lack of recognition by four NATO member states—Greece, Romania, Spain, and Slovakia—could impede its accession.[264][261] United Nations membership, which Kosovo does not have, is considered to be necessary for NATO membership.[265]

In February 2022, during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Minister of Defense Armend Mehaj requested a permanent US military base in the country and an accelerated accession process to the organization, citing an "immediate need to guarantee peace, security and stability in the Western Balkans".[5] On 3 March 2022, a resolution was passed by Kosovo's Parliament requesting that the government "take all necessary steps to join NATO, European Union, Council of Europe and other international organizations".[266]

Malta

When the North Atlantic Treaty was signed in 1949, the Mediterranean island of Malta was a dependent territory of the United Kingdom, one of the treaty's original signatories. As such, the Crown Colony of Malta shared the UK's international memberships, including NATO. Between 1952 and 1965, the headquarters of the Allied Forces Mediterranean was based in the town of Floriana, just outside Malta's capital of Valletta. When Malta gained independence in 1964, prime minister George Borg Olivier wanted the country to join NATO. Olivier was concerned that the presence of the NATO headquarters in Malta, without the security guarantees that NATO membership entailed, made the country a potential target. However, according to a memorandum he prepared at the time he was discouraged from formally submitting a membership application by Deputy Secretary General of NATO James A. Roberts. It was believed that some NATO members, including the United Kingdom, were opposed to Maltese NATO membership. As a result Olivier considered alternatives, such as seeking associate membership or unilateral security guarantees from NATO, or closing the NATO headquarters in Malta in retaliation.[268][269][270] Ultimately, Olivier supported the alliance and signed a defense agreement with the UK for use of Maltese military facilities in exchange for around £2 million a year.[271][272]

This friendly policy changed in 1971, when Dom Mintoff, of the Labour Party, was elected as prime minister. Mintoff supported neutrality as his foreign policy,[273] and the position was later enshrined into the country's constitution in 1974 as an amendment to Article 1.[274] The country joined the Non-Aligned Movement in 1979, at the same time when the British Royal Navy left its base at the Malta Dockyard. In 1995, under Prime Minister Eddie Fenech Adami of the Nationalist Party, Malta joined the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council multilateral defense forum and NATO's Partnership for Peace program. When the Labour Party regained power the following year, however, it withdrew Malta from both organizations. Though the Nationalists resumed the majority in parliament in 1998, Malta didn't rejoin the EAPC and PfP programs again until 2008, after the country had joined the European Union in 2004. Since re-joining, Malta has been building its relations with NATO and getting involved in wider projects including the PfP Planning and Review Process and the NATO Science for Peace and Security Program.[275][276]

NATO membership is not supported by any of the country's political parties, including neither the governing Labour Party nor the opposition Nationalist Party. NATO's secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg has stated that the alliance fully respects Malta's position of neutrality, and put no pressure for the country to join the alliance.[275] Polling done by the island-nation's Ministry of Foreign Affairs found in February 2022 that 63% of those surveyed supported the island's neutrality, and only 6% opposed the policy, with 14% undecided.[277] A Eurobarometer survey in May 2022 found that 75% of Maltese would however support greater military cooperation within the European Union.[278]

Moldova

Moldova gained independence in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The country's current constitution was adopted in 1994, and forbids the country from joining a military alliance, but some politicians, such as former Moldovan Minister of Defence Vitalie Marinuța, have suggested joining NATO as part of a larger European integration. Moldova joined NATO's Partnership for Peace in 1994, and initiated an Individual Partnership Action Plan in 2010.[279] Moldova also participates in NATO's peacekeeping force in Kosovo.[280] Following the 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia, NATO officials warned that Russia might seek to annex Transnistria, a breakaway Moldovan region.[281] This separatist issue could preclude Moldova from joining NATO.[279]

The current Prime Minister of Moldova, Dorin Recean, supports European Union membership, but not NATO membership.[282] Moldova's President Maia Sandu stated in January 2023 that there was "serious discussion" about joining "a larger alliance", though she didn't specifically name NATO.[280] The second largest alliance in the parliament of Moldova, the Electoral Bloc of Communists and Socialists, strongly opposes NATO membership.[283] A poll in December 2018 found that, if given the choice in a referendum, 22% of Moldovans would vote in favor of joining NATO, while 32% would vote against it and 21% would be unsure.[284] Some Moldova politicians, including former Prime Minister Iurie Leancă, have also supported the idea of unifying with neighboring Romania, which Moldova shares a language and much of its history with, and a poll in April 2021 found that 43.9% of those surveyed supported that idea. Romania is a current member of both NATO and the European Union.[285]

Serbia

.jpg.webp)

Yugoslavia's communist government sided with the Eastern Bloc at the beginning of the Cold War, but pursued a policy of neutrality following the Tito–Stalin split in 1948.[286] It was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. Since that country's dissolution most of its successor states have joined NATO, but the largest of them, Serbia, has maintained Yugoslavia's policy of neutrality.

The NATO intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992 against Bosnia-Serbian forces and the NATO bombing of targets in Serbia (then part of FR Yugoslavia) during the Kosovo War in 1999 resulted in strained relations between Serbia and NATO.[287] After the overthrow of President Slobodan Milošević Serbia wanted to improve its relations with NATO, though membership in the military alliance remained highly controversial among political parties and society.[288][289] In the years under Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić the country (then Serbia and Montenegro) did not rule out joining NATO, but after Đinđić's assassination in 2003 Serbia increasingly started preferring a course of military neutrality.[290][291] Serbia's Parliament passed a resolution in 2007 which declared Serbia's military neutrality until such time as a referendum could be held on the issue.[292] Relations with NATO were further strained following Kosovo's declaration of independence in 2008, while it was a protectorate of the United Nations with security support from NATO.

Serbia was invited to and joined NATO's Partnership for Peace program during the 2006 Riga summit, and in 2008 was invited to enter the intensified dialog program whenever the country was ready.[115] On 1 October 2008, Serbian Defence Minister Dragan Šutanovac signed the Information Exchange Agreement with NATO, one of the prerequisites for fuller membership in the Partnership for Peace program.[293] In April 2011 Serbia's request for an IPAP was approved by NATO,[294] and Serbia submitted a draft IPAP in May 2013.[295] The agreement was finalized on 15 January 2015.[296] Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, in office since 2017, reiterated in March 2022 that his government was not interested in NATO membership.[297] A poll that month suggested that 82% of Serbians opposed joining NATO, while only 10% supported the idea.[298] The minor Serbian Renewal Movement, which has two seats in the National Assembly, and the Liberal Democratic Party, which currently has none, remain the most vocal political parties in favor of NATO membership.[299] The Democratic Party abandoned its pro-NATO attitude, claiming the Partnership for Peace is enough.

Serbia maintains close relations with Russia, which are due to their shared Slavic and Eastern Orthodox culture and their stances on the Kosovo issue. Serbia and Belarus are the only European states that refused to impose sanctions on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine.[300][301][302]

Other proposals

Some individuals have proposed expanding NATO outside of Europe, although doing so would require amending Article 10 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which specifically limits new membership to "any other European State in a position to further the principles of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of the North Atlantic area."[303]

Christopher Sands of the Hudson Institute proposed Mexican membership of NATO in order to enhance NATO cooperation with Mexico and develop a "North American pillar" for regional security,[304] while Christopher Skaluba and Gabriela Doyle of the Atlantic Council promoted the idea as way to support democracy in Latin America.[305] In June 2013, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos stated his hope that Colombia's cooperation with NATO could result in NATO membership, though his Foreign Minister, Juan Carlos Pinzon, quickly clarified that Colombia is not actively seeking NATO membership.[306] In June 2018, Qatar expressed its wish to join NATO,[307] but its application was rejected by NATO.[308] In March 2019, US President Donald Trump made Brazil a major non-NATO ally, and expressed support for the eventual accession of Brazil into NATO.[309] France's Foreign Ministry responded to this by reiterating the limitations of Article 10 on new membership, and suggested that Brazil could instead seek to become a Global Partner of NATO, like Colombia.[310]

Several other current NATO Global Partners have been proposed as candidates for full membership. In 2006, Ivo Daalder, later the US Ambassador to NATO, proposed a "global NATO" that would incorporate democratic states from around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea, who all signed on as Global Partners in the 2010s, as well as Brazil, South Africa, and India.[303] In 2007, then-US presidential candidate Rudy Giuliani suggested including Singapore and Israel, among others.[311] In 2020, Trump stated that Middle Eastern countries should be admitted to NATO.[312] Because of its close ties to Europe, Cape Verde has been suggested as a future member and the government of Cape Verde suggested an interest in joining as recently as 2019.[313][314]

Internal enlargement is the process of new member states arising from the break-up of or secession from an existing member state. There have been and are a number of active separatist movements within member states. After a long history of opposition to NATO, the separatist Scottish National Party agreed at its conference in 2012 that it wished for Scotland to retain its NATO membership were it to become independent from the United Kingdom.[315] In 2014, in the run up to the self-determination referendum, the Generalitat de Catalunya published a memo suggesting an independent Catalonia would want to keep all of Spain's current foreign relationships, including NATO, though other nations, namely Belgium, have questioned whether quick membership for breakaway regions could encourage secessionist movements elsewhere.[316]

See also

References

- Harding, Luke; Koshiw, Isobel (30 September 2022). "Ukraine applies for Nato membership after Russia annexes territory". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- Jackson, John (29 June 2022). "Ukraine Sees Opportunity to Join NATO After Finland, Sweden Invite". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- "NATO launches ratification process for Sweden, Finland membership". France24. 5 July 2022. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- "Enlargement". The North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 5 May 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- "Kosovo asks U.S. for permanent military base, speedier NATO membership". Reuters. 27 February 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Fehlinger, Gunther (9 October 2022). "Malta, Austria and Ireland united in NATO 2023 – Gunther Fehlinger". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Weissman, Alexander D. (November 2013). "Pivotal Politics—The Marshall Plan: A Turning Point in Foreign Aid and the Struggle for Democracy". The History Teacher. Society for History Education. 47 (1): 111–129. JSTOR 43264189.

- Iatrides, John O.; Rizopoulos, Nicholas X. (2000). "The International Dimension of the Greek Civil War". World Policy Journal. 17 (1): 87–103. doi:10.1215/07402775-2000-2009. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40209681.

- Ruggenthaler, Peter (Fall 2011). "The 1952 Stalin Note on German Unification: The Ongoing Debate". Journal of Cold War Studies. MIT Press. 13 (4): 172–212. doi:10.1162/JCWS_a_00145. JSTOR 26924047. S2CID 57565847.

- Haftendorn, Helga (1 June 2005). "Germany's accession to NATO: 50 years on". NATO Review. NATO. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Glass, Andrew (14 May 2014). "Soviet Union establishes Warsaw Pact, May 14, 1955". Politico. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Ghosh, Palash (26 June 2012). "Why Is Turkey in NATO?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Marquina, Antonio (1998). "The Spanish Neutrality during the Second World War". American University International Law Review. 14 (1): 171–184. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- González, Miguel (23 October 2018). "America's shameful rapprochement to the Franco dictatorship". EL PAÍS English Edition. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Magone 2009, p. 439.

- Cooley, Alexander; Hopkin, Jonathan (2010). "Base Closings: The Rise and Decline of the US Military Bases Issue in Spain, 1975–2005" (PDF). International Political Science Review. 31 (4): 494–513. doi:10.1177/0192512110372975. S2CID 145801186. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- "Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo". The Times. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- Magone 2009, pp. 385–386.

- Engel, Jeffrey A. (2009). The Fall of the Berlin Wall: The Revolutionary Legacy of 1989. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973832-8. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- Sarotte, Mary Elise (September–October 2014). "A Broken Promise?". Foreign Affairs (September/October 2014). Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- Sarotte, Mary Elise (2021). Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-300-25993-3. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- Radchenko, Sergey (February 2023). "Putin's Histories". Contemporary European History. 32 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1017/S0960777322000777. S2CID 256081112.

- Baker, Peter (9 January 2022). "In Ukraine Conflict, Putin Relies on a Promise That Ultimately Wasn't". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Trachtenberg, Marc (2021). "The United States and the NATO Non-extension Assurances of 1990: New Light on an Old Problem?" (PDF). International Security. 45 (3): 162–203. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00395. S2CID 231694116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- Itzkowitz Shifrinson, Joshua R. (2016). "Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion". International Security. 40 (4): 7–44. doi:10.1162/ISEC_a_00236. S2CID 57562966.

- "Warsaw Pact ends". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 30 March 2021. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- "Warsaw Pact was dissolved 30 years ago". TVP World. PAP. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- Weigle, Marcia A. (1996). "Political Liberalism in Postcommunist Russia". The Review of Politics. 58 (3): 469–503. doi:10.1017/S0034670500020155. ISSN 0034-6705. JSTOR 1408009. S2CID 145710102.

- Horelick, Arnold L. (1 January 1995). The West's Response to Perestroika and Post-Soviet Russia (Report). Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Wallander, Celeste (October 1999). "Russian-US Relations in the Post Post-Cold War World" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "20 lat temu Polska wstąpiła do NATO". TVN24 (in Polish). 12 March 2019. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Wintour, Patrick (12 January 2022). "Russia's belief in Nato 'betrayal' – and why it matters today". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Mikhail Gorbachev: I am against all walls". Russia Beyond. 16 October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- "Memorandum of conversation between Baker, Shevardnadze and Gorbachev". National Security Archive. George Washington University. 9 February 1990. Briefing Book 613. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Kramer, Mark (1 April 2009). "The Myth of a No-NATO-Enlargement Pledge to Russia" (PDF). The Washington Quarterly. 32 (2): 39–61. doi:10.1080/01636600902773248. ISSN 0163-660X. S2CID 154322506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Kramer, Mark; Shifrinson, Joshua R. Itzkowitz (1 July 2017). "Correspondence: NATO Enlargement—Was There a Promise?". International Security. 42 (1): 186–192. doi:10.1162/isec_c_00287. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 57571871.

- Pifer, Steven (6 November 2014). "Did NATO Promise Not to Enlarge? Gorbachev Says "No"". Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Kupiecki, Robert; Menkiszak, Marek (2020). Documents Talk: NATO-Russia Relations After the Cold War. Polski Instytut Spraw Międzynarodowych. p. 375. ISBN 978-83-66091-60-3. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- Clark, Christopher; Spohr, Kristina (24 May 2015). "Moscow's account of Nato expansion is a case of false memory syndrome". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- Shifrinson, Joshua R. (2020). "NATO enlargement and US foreign policy: the origins, durability, and impact of an idea". International Politics. 57 (3): 342–370. doi:10.1057/s41311-020-00224-w. hdl:2144/41811. ISSN 1740-3898. S2CID 216168498.

- Shifrinson, Joshua R. Itzkowitz (1 April 2020). "Eastbound and down:The United States, NATO enlargement, and suppressing the Soviet and Western European alternatives, 1990–1992". Journal of Strategic Studies. 43 (6–7): 816–846. doi:10.1080/01402390.2020.1737931. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 216409925.

- Sarotte, M.E. (1 July 2019). "How to Enlarge NATO: The Debate inside the Clinton Administration, 1993–95". International Security. 44 (1): 7–41. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00353. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 198952372.

- Mitchell, Alison (23 October 1996). "Clinton Urges NATO Expansion in 1999". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Chiampan, Andrea; Lanoszka, Alexander; Sarotte, M. E. (19 October 2020). "NATO Expansion in Retrospect". The International Security Studies Forum (ISSF). Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Mehrotra, O.N. (1998). "NATO Eastward Expansion and Russian Security". Strategic Analysis. 22 (8): 1225–1235. doi:10.1080/09700169808458876. S2CID 154466181. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Irony Amid the Menace". CEPA. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Murphy, Dean E. (14 January 1995). "Chechnya Summons Uneasy Memories in Former East Bloc". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Barany 2003, pp. 190, 48–50.

- Perlez, Jane (17 November 1997). "Hungarians Approve NATO Membership". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- David & Levesque 1999, p. 200–201.

- Gheciu 2005, p. 72.

- Barany 2003, pp. 23–25.

- Barany 2003, pp. 16–18.

- Perlez, Jane (13 March 1999). "Poland, Hungary and the Czechs Join NATO". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- Wolchik & Curry 2011, p. 148.

- Peter, Laurence (2 September 2014). "Why Nato-Russia relations soured before Ukraine". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- Green, Peter S. (24 March 2003). "Slovenia Votes for Membership in European Union and NATO". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Umland, Andreas (2016). "Intermarium: The Case for Security Pact of the Countries between the Baltic and Black Seas". IndraStra Global. 2 (4): 2. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Banka, Andris (4 October 2019). "The Breakaways: A Retrospective on the Baltic Road to NATO". War on the Rocks. The Texas National Security Review. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Glasser, Susan B. (7 October 2002). "Tensions With Russia Propel Baltic States Toward NATO". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- Epstein, Rachel (2006). "Nato Enlargement and the Spread of Democracy: Evidence and Expectations". Security Studies. 14: 63–105. doi:10.1080/09636410591002509. S2CID 143878355.