Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly revered as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VIII, he was crowned in Reims at the age of 12. His mother, Blanche of Castile, effectively ruled the kingdom as regent until he came of age and continued to serve as his trusted adviser until her death. During his formative years, Blanche successfully confronted rebellious vassals and championed the Capetian cause in the Albigensian Crusade, which had been ongoing for the past two decades.

| Louis IX | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Contemporary depiction from about 1230 | |

| King of France | |

| Reign | 8 November 1226 – 25 August 1270 |

| Coronation | 29 November 1226 |

| Predecessor | Louis VIII |

| Successor | Philip III |

| Regents | See list

|

| Born | 25 April 1214 Poissy, France |

| Died | 25 August 1270 (aged 56) Tunis, North Africa |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others... | |

| House | Capet |

| Father | Louis VIII, King of France |

| Mother | Blanche of Castile |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

.jpg.webp)

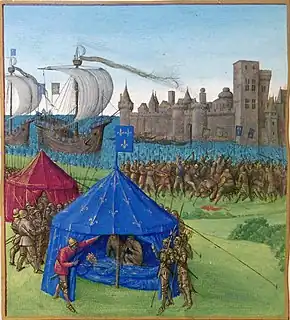

As an adult, Louis IX grappled with persistent conflicts involving some of the most influential nobles in his kingdom, including Hugh X of Lusignan and Peter of Dreux. Concurrently, England's Henry III sought to reclaim the Angevin continental holdings, only to be decisively defeated at the Battle of Taillebourg. Louis expanded his territory by annexing several provinces, including parts of Aquitaine, Maine, and Provence. Keeping a promise he made while praying for recovery from a grave illness, Louis led the ill-fated Seventh and Eighth Crusades against the Muslim dynasties that controlled North Africa, Egypt, and the Holy Land. He was captured and ransomed during the Seventh Crusade, and later succumbed to dysentery during the Eighth Crusade. His son, Philip III, succeeded him.

Louis instigated significant reforms in the French legal system, creating a royal justice mechanism that allowed petitioners to appeal judgements directly to the monarch. He abolished trials by ordeal, endeavored to terminate private wars, and incorporated the presumption of innocence into criminal proceedings. To implement his new legal framework, he established the offices of provosts and bailiffs. Louis IX's reign is often marked as an economic and political zenith for medieval France, and he held immense respect throughout Christendom. His reputation as a fair and judicious ruler led to his being solicited to mediate disputes beyond his own kingdom.[1][2]

Louis' admirers through the centuries have celebrated him as the quintessential Christian monarch. His skill as a knight and engaging manner with the public contributed to his popularity, although he was occasionally criticized as being overly pious, earning the moniker of a "monk king".[2][3] Despite his progressive legal reforms, Louis was a staunch Christian and rigorously enforced Catholic orthodoxy. He enacted harsh laws against blasphemy[4] and launched actions against France's Jewish population, including the notorious burning of the Talmud following the Disputation of Paris. Louis IX holds the distinction of being the sole canonized king of France.[5]

Sources

Much of what is known of Louis's life comes from Jean de Joinville's famous Life of Saint Louis. Joinville was a close friend, confidant, and counselor to the king. He participated as a witness in the papal inquest into Louis's life that resulted in his canonization in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII.

Two other important biographies were written by the king's confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and his chaplain, William of Chartres. While several individuals wrote biographies in the decades following the king's death, only Jean of Joinville, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and William of Chartres wrote from personal knowledge of the king and of the events they describe, and all three are biased favorably to the king. The fourth important source of information is William of Saint-Parthus's 19th-century biography,[6] which he wrote using material from the papal inquest mentioned above.

Early life

Louis was born on 25 April 1214 at Poissy, near Paris, the son of Louis the Lion and Blanche of Castile,[7] and was baptized there in La Collégiale Notre-Dame church. His grandfather on his father's side was Philip II, king of France; his grandfather on his mother's side was Alfonso VIII, king of Castile. Tutors of Blanche's choosing taught him Latin, public speaking, writing, military arts, and government.[8] He was nine years old when his grandfather Philip II died and his father became King Louis VIII.[9]

Minority (1226–1234)

Louis was 12 years old when his father died on 8 November 1226. He was crowned king within the month at Reims Cathedral. His mother, Blanche, ruled France as regent during his minority.[10] Louis's mother instilled in him her devout Christianity. She is once recorded to have said:[11]

I love you, my dear son, as much as a mother can love her child; but I would rather see you dead at my feet than that you should ever commit a mortal sin.

His younger brother Charles I of Sicily (1227–85) was created count of Anjou, thus founding the Capetian Angevin dynasty.

In 1229, when Louis was 15, his mother ended the Albigensian Crusade by signing an agreement with Raymond VII of Toulouse. Raymond VI of Toulouse had been suspected of ordering the assassination of Pierre de Castelnau, a Roman Catholic preacher who attempted to convert the Cathars.[12]

On 27 May 1234, Louis married Margaret of Provence (1221–1295); she was crowned in the cathedral of Sens the next day.[13] Margaret was the sister of Eleanor of Provence, who later married Henry III of England. The new queen's religious zeal made her a well-suited partner for the king, and they are attested to have gotten along well, enjoying riding together, reading, and listening to music. His closeness to Margaret aroused jealousy in his mother, who tried to keep the couple apart as much as she could.[14]

While his contemporaries viewed his reign as co-rule between the king and his mother, historians generally believe Louis began ruling personally in 1234, with his mother assuming a more advisory role.[1] She continued to have a strong influence on the king until her death in 1252.[10][15]

Louis as king

Arts

Louis's patronage of the arts inspired much innovation in Gothic art and architecture. The style of his court was influential throughout Europe, both because of artwork purchased from Parisian masters for export, and by the marriage of the king's daughters and other female relatives to foreigners. They became emissaries of Parisian models and styles elsewhere. Louis's personal chapel, the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, which was known for its intricate stained-glass windows, was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis is believed to have ordered the production of the Morgan Bible and the Arsenal Bible, both deluxe illuminated manuscripts.

During the so-called "golden century of Saint Louis", the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. Saint Louis was regarded as "primus inter pares", first among equals, among the kings and rulers of the continent. He commanded the largest army and ruled the largest and wealthiest kingdom, the European centre of arts and intellectual thought at the time. The foundations for the notable college of theology, later known as the Sorbonne, were laid in Paris about the year 1257.[16]

Arbitration

The prestige and respect felt by Europeans for King Louis IX were due more to the appeal of his personality than to military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince and embodied the whole of Christendom in his person. His reputation for fairness and even saintliness was already well established while he was alive, and on many occasions he was chosen as an arbiter in quarrels among the rulers of Europe.[1]

Shortly before 1256, Enguerrand IV, Lord of Coucy, arrested and without trial hanged three young squires of Laon, whom he accused of poaching in his forest. In 1256 Louis had the lord arrested and brought to the Louvre by his sergeants. Enguerrand demanded judgment by his peers and trial by battle, which the king refused because he thought it obsolete. Enguerrand was tried, sentenced, and ordered to pay 12,000 livres. Part of the money was to pay for masses to be said in perpetuity for the souls of the men he had hanged.

In 1258, Louis and James I of Aragon signed the Treaty of Corbeil to end areas of contention between them. By this treaty, Louis renounced his feudal overlordship over the County of Barcelona and Roussillon, which was held by the King of Aragon. James in turn renounced his feudal overlordship over several counties in southern France, including Provence and Languedoc. In 1259 Louis signed the Treaty of Paris, by which Henry III of England was confirmed in his possession of territories in southwestern France, and Louis received the provinces of Anjou, Normandy (Normandie), Poitou, Maine, and Touraine.[10]

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Integralism |

|---|

|

The perception of Louis IX by his contemporaries as the exemplary Christian prince was reinforced by his religious zeal. Louis was an extremely devout Catholic, and he built the Sainte-Chapelle ("Holy Chapel"),[1] located within the royal palace complex (now the Paris Hall of Justice), on the Île de la Cité in the centre of Paris. The Sainte Chapelle, a prime example of the Rayonnant style of Gothic architecture, was erected as a shrine for what Louis believed to be the Crown of Thorns and a fragment of the True Cross, supposed precious relics of the Passion of Christ. He acquired these in 1239–41 from Emperor Baldwin II of the Latin Empire of Constantinople by agreeing to pay off Baldwin's debt to the Venetian merchant Niccolo Quirino, for which Baldwin had pledged the Crown of Thorns as collateral.[17] Louis IX paid the exorbitant sum of 135,000 livres to clear the debt.

In 1230, the King forbade all forms of usury, defined at the time as any taking of interest and therefore covering most banking activities. Louis used these anti-usury laws to extract funds from Jewish and Lombard moneylenders, with the hopes that it would help pay for a future crusade.[16] Louis also oversaw the Disputation of Paris in 1240, in which Paris's Jewish leaders were imprisoned and forced to admit to anti-Christian passages in the Talmud, the major source of Jewish commentaries on the Bible and religious law. As a result of the disputation, Pope Gregory IX declared that all copies of the Talmud should be seized and destroyed. In 1242, Louis ordered the burning of 12,000 Talmudim, along with other important Jewish books and scripture.[18] The edict against the Talmud was eventually overturned by Gregory IX's successor, Innocent IV.[5]

Louis also expanded the scope of the Inquisition in France. He set the punishment for blasphemy to mutilation of the tongue and lips.[4] The area most affected by this expansion was southern France, where the Cathar sect had been strongest. The rate of confiscation of property from the Cathars and others reached its highest levels in the years before his first crusade and slowed upon his return to France in 1254.

In 1250, Louis headed a crusade to Egypt and was taken prisoner. During his captivity, he recited the Divine Office every day. After his release against ransom, he visited the Holy Land before returning to France.[11] In these deeds, Louis IX tried to fulfill what he considered the duty of France as "the eldest daughter of the Church" (la fille aînée de l'Église), a tradition of protector of the Church going back to the Franks and Charlemagne, who had been crowned by Pope Leo III in Rome in 800. The kings of France were known in the Church by the title "most Christian king" (Rex Christianissimus).

Louis founded many hospitals and houses: the House of the Filles-Dieu for reformed prostitutes; the Quinze-Vingt for 300 blind men (1254), and hospitals at Pontoise, Vernon, and Compiégne.[19]

St. Louis installed a house of the Trinitarian Order at Fontainebleau, his chateau and estate near Paris. He chose Trinitarians as his chaplains and was accompanied by them on his crusades. In his spiritual testament he wrote, "My dearest son, you should permit yourself to be tormented by every kind of martyrdom before you would allow yourself to commit a mortal sin."[11]

Louis authored and sent the Enseignements, or teachings, to his son Philip III. The letter outlined how Philip should follow the example of Jesus Christ in order to be a moral leader.[20] The letter is estimated to have been written in 1267, three years before Louis's death.[21]

Personal reign (1235–1266)

Seventh Crusade

Louis and his followers landed in Egypt on 4 or 5 June 1249 and began their campaign with the capture of the port of Damietta.[22][23] This attack caused some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan, Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub, was on his deathbed. However, the march of Europeans from Damietta toward Cairo through the Nile River Delta went slowly. The seasonal rising of the Nile and the summer heat made it impossible for them to advance.[16] During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and the sultan's wife Shajar al-Durr set in motion a shift in power that would make her Queen and eventually result in the rule of the Egyptian army of the Mamluks.

On 8 February 1250, Louis lost his army at the Battle of Fariskur and was captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated in return for a ransom of 400,000 livres tournois (roughly 80 million USD today) and the surrender of the city of Damietta.[24]

Four years in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Upon his liberation from captivity in Egypt, Louis IX devoted four years to fortifying the Kingdom of Jerusalem, focusing his efforts in Acre, Caesarea, and Jaffa. He generously utilized his resources to aid the Crusaders in reconstructing their defenses[25] and actively engaged in diplomatic endeavors with the Islamic powers of Syria and Egypt. In spring 1254, Louis and his remaining forces made their return to France.[22]

Louis maintained regular correspondence and envoy exchanges with the Mongol rulers of his era. During his first crusade in 1248, he received envoys from Eljigidei, the Mongol military leader stationed in Armenia and Persia.[26] Eljigidei proposed that Louis should launch an offensive in Egypt while he targeted Baghdad to prevent the unification of the Muslim forces in Egypt and Syria. In response, Louis sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as a delegate to the Khangan Güyük Khan (r. 1246–1248) in Mongolia. However, Güyük's death preceded the arrival of the emissary, and his widow and acting regent, Oghul Qaimish, rejected the diplomatic proposition.[27]

Louis sent another representative, the Franciscan missionary and explorer William of Rubruck, to the Mongol court. Rubruck visited the Khagan Möngke (r. 1251–1259) in Mongolia and spent several years there. In 1259, Berke, the leader of the Golden Horde, demanded Louis's submission.[28] In contrast, Mongol emperors Möngke and Khubilai's brother, the Ilkhan Hulegu, sent a letter to the French king, soliciting his military aid; this letter, however, never reached France.[29]

Later reign (1267–1270)

Eighth Crusade and death

In a parliament held at Paris, 24 March 1267, Louis and his three sons "took the cross." On hearing the reports of the missionaries, Louis resolved to land at Tunis, and he ordered his younger brother, Charles of Anjou, to join him there. The crusaders, among whom was the English prince Edward Longshanks, landed at Carthage 17 July 1270, but disease broke out in the camp.[25]

Louis died at Tunis on 25 August 1270, in an epidemic of dysentery that swept through his army.[30][31][32] According to European custom, his body was subjected to the process known as mos Teutonicus prior to his remains being returned to France.[33] Louis was succeeded as King of France by his son, Philip III.

Louis's younger brother, Charles I of Naples, preserved his heart and intestines, and conveyed them for burial in the Cathedral of Monreale near Palermo.[34]

Louis's bones were carried overland in a lengthy processional across Sicily, Italy, the Alps, and France, until they were interred in the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis in May 1271[35] Charles and Philip III later dispersed a number of relics to promote Louis's veneration.[36]

Children

- Blanche (12 July/4 December 1240 – 29 April 1244), died in infancy.[7]

- Isabella (2 March 1241 – 28 January 1271), married Theobald II of Navarre.[37]

- Louis (23 September 1243/24 February 1244 – 11 January/2 February 1260). Betrothed to Berengaria of Castile in Paris on 20 August 1255.[38]

- Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), married firstly to Isabella of Aragon in 1262 and secondly to Maria of Brabant in 1274.

- John (1246/1247 – 10 March 1248), died in infancy.[7]

- John Tristan (8 April 1250 – 3 August 1270), Count of Valois, married Yolande II, Countess of Nevers.[7]

- Peter (1251 – 6/7 April 1284),[7] Count of Perche and Alençon, married Joanne of Châtillon.

- Blanche (early 1253 – 17 June 1320), married Ferdinand de la Cerda, Infante of Castile.[7]

- Margaret (early 1255 – July 1271), married John I, Duke of Brabant.[7]

- Robert (1256 – 7 February 1317), Count of Clermont,[7] married Beatrice of Burgundy. The French crown devolved upon his male-line descendant, Henry IV (the first Bourbon king), when the legitimate male line of Philip III died out in 1589.

- Agnes (1260 – 19/20 December 1327), married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy.[7]

Louis and Margaret's two children who died in infancy were first buried at the Cistercian abbey of Royaumont. In 1820 they were transferred and reinterred to Saint-Denis Basilica.[39]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Louis IX of France |

|---|

Veneration as a saint

Louis | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) San Luis, Rey de Francia (English: Saint Louis, King of France) by Francisco Pacheco | |

| King of France Confessor | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Canonized | 11 July 1297, Rome, Papal States by Pope Boniface VIII |

| Feast | 25 August |

| Attributes | The Crown of Thorns, crown, sceptre, globus cruciger, sword, fleur-de-lis, mantle, and the other parts of the French regalia |

| Patronage | |

Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the canonization of Louis in 1297;[40] he is the only French king to be declared a saint.[41] Louis IX is often considered the model of the ideal Christian monarch.[40]

Named in his honour, the Sisters of Charity of St. Louis is a Roman Catholic religious order founded in Vannes, France, in 1803.[42] A similar order, the Sisters of St Louis, was founded in Juilly in 1842.[43][44]

He is honoured as co-patron of the Third Order of St. Francis, which claims him as a member of the Order. When he became king, over a hundred poor people were served meals in his house on ordinary days. Often the king served these guests himself. His acts of charity, coupled with his devout religious practices, gave rise to the legend that he joined the Third Order of St. Francis, though it is unlikely that he ever actually joined the order.[8]

The Catholic Church and Episcopal Church honor him with a feast day on 25 August.[45][46]

Things named after Saint Louis

- The French royal Order of Saint Louis (1693–1790 and 1814–1830)[47]

Places

Many countries in which French speakers and Catholicism were prevalent named places after King Louis:

- San Luis Province in Argentina[48]

- San Luis Potosí in Mexico[49]

- Multiple locations in the United States

- St. Louis, Missouri, named by French colonists[50]

- Multiple locations in France[50]

- Île Saint-Louis, an island in the river Seine, Paris[51]

- Saint-Louis, New Caledonia

- Multiple locations in Canada[50]

- Saint-Louis, Senegal[50]

- São Luís, Maranhão in Brazil[52]

- The Philippines

Buildings

- France

- Hôpital Saint-Louis, hospital in the 10th arrondissement of Paris[55]

- The Cathédrale Saint-Louis de Versailles in Versailles[56]

- United States

- The Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, completed in 1834 in St. Louis, Missouri[57]

- The Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis, completed in 1914 in St. Louis, Missouri [58]

- The St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans[59]

- The St. Louis King of France Catholic Church and School, in Metairie, Louisiana [60]

- Saint Louis Catholic High School, in Lake Charles, Louisiana

- Saint Louis King of France Catholic Church and School, in Austin, Texas

- Saint Louis Catholic Church, in Waco, Texas

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, Oceanside, California, founded 12 June 1798

- San Luis Rey Mission, Chamberino, New Mexico

- St. Louis Roman Catholic Church in Buffalo, New York[61] (Mother Church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Buffalo)[62]

- The national church of France in Rome: San Luigi dei Francesi in Italian, or Saint Louis of France in English[63]

- The Cathedral of St Louis in Plovdiv, Bulgaria[64]

- The Cathedral of St Louis in Carthage, Tunisia, so named because Louis IX died at that approximate location in 1270[65]

- The Church of St Louis in Moscow, Russia[66]

- India

- Rue Saint Louis of Pondicherry[67]

- St. Louis Church, Dahisar East, Mumbai. (https://stlouischurchdahisar.in/)

- The Convent of Saint Louis and Catholic High School in Carrickmacross, Ireland.

Notable portraits

- United States

- A bas-relief of St. Louis is one of the carved portraits of historic lawmakers that adorn the chamber of the United States House of Representatives.

- Saint Louis is also portrayed on a frieze depicting a timeline of important lawgivers throughout world history, on the North Wall of the Courtroom at the Supreme Court of the United States.[68]

- A statue of St. Louis by the sculptor John Donoghue stands on the roofline of the New York State Appellate Division Court at 27 Madison Avenue in New York City.

- The Apotheosis of St. Louis is an equestrian statue of the saint, by Charles Henry Niehaus, that stands in front of the Saint Louis Art Museum in Forest Park.

- A heroic portrait by Baron Charles de Steuben hangs in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Baltimore. An 1821 gift of King Louis XVIII of France, it depicts St. Louis burying his plague-stricken troops before the siege of Tunis at the beginning of the Eighth Crusade in 1270.

In fiction

- Davis, William Stearns, "Falaise of the Blessed Voice" aka "The White Queen". New York, NY: Macmillan, 1904

- Peter Berling, The Children of the Grail

- Jules Verne, "To the Sun?/Off on a Comet!" A comet takes several bits of the Earth away when it grazes the Earth. Some people, taken up at the same time, find the Tomb of Saint Louis is one of the bits, as they explore the comet.

- Adam Gidwitz, The Inquisitor's Tale

- Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia. It is likely that Dante hides the figure of the Saint King behind the Veltro, the Messo di Dio, the Veglio di Creta and the "515", which is a duplicate of the Messo. This is a trinitarian representation to oppose to the analogous representation of his nephew Philip IV the Fair, as the Beast from the Sea. The idea came to Dante from the transposition of the Revelation of St. John in the history, studied from the abbot and theologian Joachim of Fiore.[69]

- Theodore de Bainville, poem, "La Ballade des Pendus (Le Verger du Roi Louis)"; musicalized by Georges Brassens.

Music

- Arnaud du Prat, Paris canon; Rhymed, chanted office for St. Louis, 1290, Sens Bib. Mun. MS6, and elsewhere.

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet for Saint Louis, H.320, for 1 voice, 2 treble instruments (?) and continuo 1675.

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem santi Ludovici Regis Galliae canticum tribus vocibus cum symphonia, H.323, for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo (1678 ?)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae, H.332, for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo 1683)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae canticum, H.365 & H.365 a, for soloists, chorus, woodwinds, strings and continuo (1690)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae, H.418, for soloists, chorus, 2 flutes, 2 violins and continuo (1692–93)

References

- "Goyau, Georges. 'St. Louis IX.' The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 24 Feb. 2013". Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Louis IX, king of France". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Bouquet, Martin (1840–1904). Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France. Tome 23 / [éd. par Dom Martin Bouquet,...] ; nouv. éd. publ. sous la dir. de M. Léopold Delisle,... (in French).

- Bobineau, Olivier (8 December 2011). "Retour de l'ordre religieux ou signe de bonne santé de notre pluralisme laïc ?". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- "The Pope Who Saved the Talmud". The 5 Towns Jewish Times. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Vie de St Louis, ed. H.-F. Delaborde, Paris, 1899

- Richard 1983, p. xxiv.

- "Saint Louis, King of France, Archdiocese of St. Louis, MO". Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Plaque in the church, Collégiale Notre-Dame, Poissy, France.

- "Louis IX". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- Fr. Paolo O. Pirlo, SHMI (1997). "St. Louis". My First Book of Saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate – Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 193–194. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.

- Sumption 1978, p. 15.

- Richard 1983, p. 64.

- Richard 1983, p. 65.

- Shadis 2010, pp. 17–19.

- "Lives of Saints". John J. Crawley & Co., Inc. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Guerry, Emily (18 April 2019). "Dr". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- "Burning of the Talmud". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Goyau, Pierre-Louis-Théophile-Georges (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

- Greer Fein, Susanna. "Art. 94, Enseignements de saint Lewis a Philip soun fitz: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- O'Connell, David (1972). The teachings of Saint Louis; a critical text. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press. pp. 46–49.

- "Crusades: Crusades of the 13th century". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- Tyerman 2006, p. 787.

- Tyerman 2006, p. 796.

- "Bréhier, Louis. "Crusades." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 24 Feb. 2013". Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Jackson 1980, p. 481-513.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Durham, New Carolina: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813513041. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1): 1–44. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41933117.

- Aigle, Denise (2005). "The Letters of Eljigidei, H¨uleg¨u and Abaqa: Mongol overtures or Christian Ventriloquism?" (PDF). Inner Asia. 7 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1163/146481705793646883. S2CID 161266055. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Magill & Aves 1998, p. 606.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 1004.

- Lock 2013, p. 183.

- Westerhof 2008, p. 79.

- Gaposchkin 2008, p. 28.

- Gaposchkin 2008, pp. 28–29.

- Gaposchkin 2008, pp. 28–30, 76.

- Jordan 2017, p. 25.

- Jordan 2017, pp. 25–26.

- Brown 1990, p. 810.

- Louis IX, Oxford Dictionary of Saints, (Oxford University Press, 2004), 326.

- "Louis". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Vol. 7 (15 ed.). 1993. p. 497. ISBN 978-0852295717.

- "Who We Are". Sisters of Charity of St. Louis. 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "Our Father and Patron St. Louis / St. Louis, King of France, 1214–1270 AD" St. Louis Handbook for Schools. Sisters of St Louis. p. 8.

- "Our history". Sisters of St Louis. 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "Optional Memorial of Saint Louis of France | USCCB". bible.usccb.org. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- Mazas, Alexandre (1860). Histoire de l'ordre royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis depuis son institution en 1693 jusqu'en 1830 (in French). Firmin Didot frères, fils et Cie. p. 28.

- "San Luis". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- "Historia". City of San Luis Potosí (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Everett-Heath, John (2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 1436. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2.

- "Ile Saint Louis – Paris". francemonthly.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Everett-Heath, John (2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 1369. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2.

- "Municipality of San Luis | Provincial Government of Aurora". Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "San Luis, Batangas: Historical Data". Batangas History, Culture & Folklore. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- "Histoire de l'hôpital Saint-Louis" (PDF). Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- "Versailles Saint-Louis Cathedral: guided tour". www.ParisCityVision.com. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "History & the Story of St. Louis IX". Basilica of Saint Louis, King of France. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Brief History of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis". The Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "Our History". Cathedral-Basilica of Saint Louis King of France. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "St. Louis King of France Catholic School". St. Louis King of France Catholic School.

- "History – St. Louis RC Church".

- "Saint Louis Roman Catholic Church in Buffalo, USA".

- Bassani Grampp, Florian (August 2008). "On a Roman Polychoral Performance in August 1665". Early Music. 36 (3): 415–433. doi:10.1093/em/can095. JSTOR 27655211. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- Plovdiv, Visit. "Catholic Cathedral 'Saint Louis'". www.visitplovdiv.com. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Artaud de La Ferrière, Alexis (May 2019). "Listen Articles The Catholic Church in Tunisia: a transliminal institution between religion and nation". The Journal of North African Studies. 25 (3): 415–446. doi:10.1080/13629387.2019.1611428. S2CID 164493102.

- "Приход св. Людовика в Москве – Приход св. Людовика в Москве". ru.eglise.ru. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo – Rue Saint Louis in Pondicherry India". Alamy. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- "US Supreme Court Courtroom Friezes" (PDF). Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- Lombardi, Giancarlo (2022). L'Estetica Dantesca del Dualismo (in Italian). Borgomanero, Novara, Italy: Giuliano Ladolfi Editore. ISBN 978-8866446620.

Bibliography

- Brown, Elizabeth A. R. (Autumn 1990). "Authority, the Family, and the Dead in Late Medieval France". French Historical Studies. 16 (4): 803–832. doi:10.2307/286323. JSTOR 286323.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1928-0290-9.

- Davis, Jennifer R. (Autumn 2010). "The Problem of King Louis IX of France: Biography, Sanctity, and Kingship". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (2): 209–225. doi:10.1162/JINH_a_00050. S2CID 144928195.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-062-70056-8. OL 1715499M.

- Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia (2008). The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-47625-9. OL 16365443M.

- Jackson, Peter (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review. 95 (376): 481–513. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCV.CCCLXXVI.481. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 568054.

- Jordan, William Chester (1979). Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study in Rulership. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05285-4. OL 4433805M.

- —— (2017). "A Border Policy? Louis IX and the Spanish Connection". In Liang, Yuen-Gen; Rodriguez, Jarbel (eds.). Authority and Spectacle in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honor of Teofilo F. Ruiz. Routledge. OL 33569507M.

- Le Goff, Jacques (2009). Saint Louis. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-03381-1.

- Lock, Peter (2013). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-13137-1.

- Magill, Frank Northen; Aves, Alison, eds. (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 1-5795-8041-6.

- Shadis, Miriam (2010). Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) and Political Women in the High Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23473-7.

- Richard, Jean (1983). Lloyd, Simon (ed.). Saint Louis: Crusader King of France. Translated by Birrell, Jean. Cambridge University Press.

- Streyer, J.R. (1962). "The Crusades of Louis IX". In Setton, K.M. (ed.). A History of the Crusades. Vol. II. Philadelphia. pp. 487–521.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sumption, Jonathan (1978). The Albigensian Crusade. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20002-3. OL 7857399M.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Westerhof, Danielle (16 October 2008). Death and the Noble Body in Medieval England. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-843-83416-8.

External links

- John de Joinville. Memoirs of Louis IX, King of France. Chronicle, 1309.

- Saint Louis in Medieval History of Navarre

- Site about The Saintonge War between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England.

- Account of the first Crusade of Saint Louis from the perspective of the Arabs..

- A letter from Guy, a knight, concerning the capture of Damietta on the sixth Crusade with a speech delivered by Saint Louis to his men.

- Etext full version of the Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville, a biography of Saint Louis written by one of his knights

- "St. Lewis, King of France", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- "Man of the Middle Ages, Saint Louis, King of France", Archdiocese of St. Louis, MO