Sati (practice)

Sati or suttee[note 1] was a historical practice in which a widow sacrifices herself by sitting atop her deceased husband's funeral pyre.[2][3][4][5][6] Although it is debated whether it received scriptural mention in early Hinduism, it has been linked to related Hindu practices in the Indo-Aryan-speaking regions of India which diminished the rights of women, especially those to the inheritance of property.[note 2][note 3] A cold form of sati, or the neglect and casting out of Hindu widows, has been prevalent from ancient times.[9][note 4] Greek sources from around 300 BCE make isolated mention of sati,[11][12][13] but it probably developed into a real fire sacrifice in the medieval era within the northwestern Rajput clans to which it initially remained limited,[14] to become more widespread during the late medieval era.[15][16][17]

During the early-modern Mughal period of 1526–1857, it was notably associated with elite Hindu Rajput clans in western India, marking one of the points of divergence between Hindu Rajputs and the Muslim Mughals, who banned the practice.[18] In the early 19th century, the British East India Company, in the process of extending its rule to most of India, initially tolerated the practice; William Carey, a British Christian evangelist, noted 438 incidents within a 30-mile (48-km) radius of the capital, Calcutta, in 1803, despite its ban within Calcutta.[19] Between 1815 and 1818 the number of incidents of sati in Bengal doubled from 378 to 839. Opposition to the practice of sati by evangelists like Carey, and by Hindu reformers such as Ram Mohan Roy ultimately led the British Governor-General of India Lord William Bentinck to enact the Bengal Sati Regulation, 1829, declaring the practice of burning or burying alive of Hindu widows to be punishable by the criminal courts.[20][21][22] Other legislation followed, countering what the British perceived to be interrelated issues involving violence against Hindu women, including the Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856, Female Infanticide Prevention Act, 1870, and Age of Consent Act, 1891. Ram Mohan Roy observed that when women allow themselves to be consigned to the funeral pyre of a deceased husband it results not just "from religious prejudices only", but, "also from witnessing the distress in which widows of the same rank in life are involved, and the insults and slights to which they are daily subject."[23]

Isolated incidents of sati were recorded in India in the late-20th century, leading the Indian government to promulgate the Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, criminalising the aiding or glorifying of sati.[24] The modern laws have proved difficult to implement; as of 2020, at least 250 sati temples existed in India in which prayer ceremonies, or pujas, were performed to glorify the avatar of a mother goddess who immolated herself on a husband's funeral pyre after hearing her father insult him; prayers were also performed to the practice of a wife immolating herself alive on a deceased husband's funeral pyre.[note 5]

Etymology and usage

Sati (Sanskrit: सती / satī) is derived from the name of the goddess Sati, who self-immolated because she was unable to bear her father Daksha's humiliation of her and her husband Shiva.

The term sati was originally interpreted as "chaste woman". Sati appears in Hindi and Sanskrit texts, where it is synonymous with "good wife";[25] the term suttee was commonly used by Anglo-Indian English writers.[26] The word Sati, therefore, originally referred to the woman, rather than the rite. Variants are:

- Sativrata, an uncommon and seldom used term,[27] denotes the woman who makes a vow, vrata, to protect her husband while he is alive and then die with her husband.

- Satimata denotes a venerated widow who committed sati.[28]

The rite itself had technical names:

- Sahagamana ("going with") or sahamarana ("dying with").

- Anvarohana ("ascension" to the pyre) is occasionally met, as well as satidaha as terms to designate the process.[29]

- Satipratha is also, on occasion, used as a term signifying the custom of burning widows alive.[30]

The Indian Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 Part I, Section 2(c) defines sati as the act or rite itself.[31]

Origin and spread

The origins and spread of the practice of sati are complex and much debated questions, without a general consensus.[15][17] It has been speculated that rituals such as widow sacrifice or widow burning have prehistoric roots.[note 6] The archaeologist Elena Efimovna Kuzmina has listed several parallels between the burial practices of the ancient Asiatic steppe Andronovo cultures (fl. 1800–1400 BCE) and the Vedic Age.[35] She considers sati to be a largely symbolic double burial or a double cremation, a feature she argues is to be found in both cultures,[36] with neither culture observing it strictly.[37]

Vedic symbolic practice

According to Romila Thapar, in the Vedic period, when "mores of the clan gave way to the norms of caste", wives were obliged to join in quite a few rituals but without much authority. A ritual with support in a Vedic text was a "symbolic self-immolation" which it is believed a widow of status needed to perform at the death of her husband, the widow subsequently marrying her husband's brother.[38] In later centuries, the text was cited as the origin of Sati, with a variant reading allowing the authorities to insist that the widow sacrifice herself in reality by joining her deceased husband on the funeral pyre.[38]

Anand A. Yang notes that the Rig Veda refers to a "mimetic ceremony" where a "widow lay on her husband's funeral pyre before it was lit but was raised from it by a male relative of her dead husband."[39] According to Yang, the word agre, "to go forth", was (probably in the 16th century) mistranslated into agneh, "into the fire", to give Vedic sanction for sati.[39]

Early medieval origins

.jpg.webp)

Sati as the burning of a widow with her deceased husband seems to have been introduced in the post-Gupta times, after 500 CE.[42] Vidya Dehejia states that sati was introduced late into Indian society, and became regular only after 500 CE.[43] According to Ashis Nandy, the practice became prevalent from the 7th century onward and declined to its elimination in the 17th century to gain resurgence in Bengal in the 18th century.[44] Historian Roshen Dalal postulates that its mention in some of the Puranas indicates that it slowly grew in prevalence from 5th–7th century and later became an accepted custom around 1000 CE among those of higher classes, especially the Rajputs.[45][15] One of the stanzas in the Mahabharata describes Madri's suicide by sati, but is likely an interpolation given that it has contradictions with the succeeding verses.[46]

According to Dehejia, sati originated within the kshatriyas (warrior) aristocracy and remained mostly limited to the warrior class among Hindus.[47] According to Thapar, the introduction and growth of the practice of sati as a fire sacrifice is related to new Kshatriyas, who forged their own culture and took some rules "rather literally",[42] with a variant reading of the Veda turning the symbolic practice into the practice of a widow burning herself with her husband.[38] Thapar further points to the "subordination of women in patriarchal society", "changing 'systems of kinship'", and "control over female sexuality" as factors in the rise of sati.[48]

Medieval spread

The practice of sati was emulated by those seeking to achieve high status of the royalty and the warriors as part of the process of sanskritisation,[15] but its spread was also related to the centuries of Islamic invasion and its expansion in South Asia,[15][49] and to the hardship and marginalisation that widows endured.[50] Crucial was the adoption of the practice by Brahmins, despite prohibitions for them to do so.[51]

Sati acquired an additional meaning as a means to preserve the honour of women whose men had been slain,[15] akin to the practice of jauhar,[52][53] with the ideologies of jauhar and sati reinforcing each other.[52] Jauhar was originally a self-chosen death for noble women facing defeat in war, and practised especially among the warrior Rajputs.[52] Oldenburg posits that the enslavement of women by Greek conquerors may have started this practice,[17] On attested Rajput practice of jauhar during wars, and notes that the kshatriyas or Rajput castes, not the Brahmins, were the most respected community in Rajasthan in north-west India, as they defended the land against invaders centuries before the coming of the Muslims.[54] She proposes that Brahmins of the north-west copied Rajput practices, and transformed sati ideologically from the 'brave woman' into the 'good woman'.[54] From those Brahmins, the practice spread to other non-warrior castes.[52]

According to David Brick of Yale University, sati, which was initially rejected by the Brahmins of Kashmir, spread among them in the later half of the first millennium. Brick's evidence for claiming this spread is the mention of sati-like practices in the Vishnu Smriti (700–1000 CE), which is believed to have been written in Kashmir. Brick argues that the author of the Vishnu Smriti may have been mentioning practices existing in his own community. Brick notes that the dates of other Dharmasastra texts mentioning sahagamana are not known with certainty, but posits that the priestly class throughout India was aware of the texts and the practice itself by the 12th century.[16] According to Anand Yang, it was practised in Bengal as early as the 12th century, where it was originally practised by the Kshatriya caste and later spread to other upper and lower castes including Brahmins.[51] Julia Leslie writes that the practice increased among Bengal Brahmins between 1680 and 1830, after widows gained inheritance rights.[50]

Colonial era revival

Sati practice resumed during the colonial era, particularly in significant numbers in colonial Bengal Presidency.[55] Three factors may have contributed this revival: sati was believed to be supported by Hindu scriptures by the 19th century; sati was encouraged by unscrupulous neighbours as it was a means of property annexation from a widow who had the right to inherit her dead husband's property under Hindu law, and sati helped eliminate the inheritor; poverty was so extreme during the 19th century that sati was a means of escape for a woman with no means or hope of survival.[55]

Daniel Grey states that the understanding of origins and spread of sati were distorted in the colonial era because of a concerted effort to push "problem Hindu" theories in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[56] Lata Mani wrote that all of the parties during the British colonial era that debated the issue subscribed to the belief in a "golden age" of Indian women followed by a decline in concurrence to the Muslim conquests. This discourse also resulted in promotion of a view of British missionaries rescuing "Hindu India from Islamic tyranny".[57] Several British missionaries who had studied classical Indian literature attempted to employ Hindu scriptural interpretations in their missionary work to convince their followers that Sati was not mandated by Hinduism.[58]

History

Early Greek sources

Among those that do reference the practice, the lost works of the Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia, who travelled to India with the expedition of Alexander the Great in c. 327 BCE, are preserved in the fragments of Strabo. There are different views by authors on what Aristobulus hears as widows of one or more tribes in India performing self-sacrifice on the husband's pyre, one author also mentions that widows who declined to die were held in disgrace.[11][12][13] In contrast, Megasthenes who visited India during 300 BCE does not mention any specific reference to the practice,[59][13] which Dehejia takes as an indication that the practice was non-existent then.[60]

Diodorus writes about the wives of Ceteus, the Indian captain of Eumenes, competing for burning themselves after his death in the Battle of Paraitakene (317 BCE). The younger one is permitted to mount the pyre. Modern historians believe Diodorus's source for this episode was the eyewitness account of the now lost historian Hieronymus of Cardia. Hieronymus' explanation of the origin of sati appears to be his own composite, created from a variety of Indian traditions and practices to form a moral lesson upholding traditional Greek values.[61] Modern scholarship has generally treated this instance as an isolated incident, not representative of general culture.

Two other independent sources that mention widows who voluntarily joined their husbands' pyres as a mark of their love are Cicero and Nicolaus of Damascus.[62]

Early Sanskrit sources

Some of the early Sanskrit authors like Daṇḍin in Daśakumāracarita and Banabhatta in Harshacharita mention that women who burnt themselves wore extravagant dresses. Bana tells about Yasomati who, after choosing to mount the pyre, bids farewell to her relatives and servants. She then decks herself in jewellery which she later distributes to others.[63] Although Prabhakaravardhana's death is expected, Arvind Sharma suggests it is another form of sati.[64] The same work mentions Harsha's sister Rajyasri trying to commit sati after her husband died.[65][66] In Kadambari, Bana greatly opposes sati and gives examples of women who did not choose sahgamana.[67]

Sangam literature

Padma Sree asserts that other evidence for some form of sati comes from Sangam literature in Tamilkam: for instance the Silappatikaram written in the 2nd century CE. In this tale, Kannagi, the chaste wife of her wayward husband Kovalan, burns Madurai to the ground when her husband is executed unjustly, then climbs a cliff to join Kovalan in heaven. She became an object of worship as a chaste wife, called Pattini in Sinhala and Kannagiamman in Tamil, and is still worshipped today. An inscription in an urn burial from the 1st century CE tells of a widow who told the potter to make the urn big enough for both her and her husband. The Manimekalai similarly provides evidence that such practices existed in Tamil lands, and the Purananuru claims widows prefer to die with their husband due to the dangerous negative power associated with them. However she notes that this glorification of sacrifice was not unique to women: just as the texts glorified "good" wives who sacrificed themselves for their husbands and families, "good" warriors similarly sacrificed themselves for their kings and lands. It is even possible that the sacrifice of the "good" wives originated from the warrior sacrifice tradition. Today, such women are still worshipped as Gramadevatas throughout South India.[68]

Inscriptional evidence

According to Axel Michaels, the first inscriptional evidence of the practice is from Nepal in 464 CE, and in India from 510 CE.[69] The early evidence suggests that widow-burning practice was seldom carried out in the general population.[69] Centuries later, instances of sati began to be marked by inscribed memorial stones called Sati stones. According to J.C. Harle, the medieval memorial stones appear in two forms – viragal (hero stone) and satigal (sati stone), each to memorialise something different. Both of these are found in many regions of India, but "rarely if ever earlier in date than the 8th or 9th century".[70] Numerous memorial sati stones appear 11th-century onwards, states Michaels, and the largest collections are found in Rajasthan.[69] There have been few instances of sati in the Chola Empire in South India. Vanavan Mahadevi, the mother of Rajaraja Chola I (10th century) and Viramahadevi the queen of Rajendra Chola I (11th century) both committed Sati upon their husband's death by ascending the pyre.[71][72] The 510 CE inscription at Eran mentioning the wife of Goparaja, a vassal of Bhanugupta, burning herself on her husband's pyre is considered to be a Sati stone.[40]

Practice in Hindu-influenced cultures outside India

The early 14th-century CE traveller of Pordenone mentions wife burning in Zampa (Champa), in nowadays south/central Vietnam.[73][note 7] Anant Altekar states that sati spread with Hindu migrants to Southeast Asian islands, such as to Java, Sumatra and Bali.[75] According to Dutch colonial records, this was however a rare practice in Indonesia, one found in royal households.[76]

In Cambodia, both the lords and the wives of a dead king voluntarily burnt themselves in the 15th and 16th centuries.[77][note 8] According to European traveller accounts, in 15th century Mergui, in present-day extreme south Myanmar, widow burning was practised.[80] A Chinese pilgrim from the 15th century seems to attest the practice on islands called Ma-i-tung and Ma-i (possibly Belitung (outside Sumatra) and Northern Philippines, respectively).[81]

According to the historian K.M. de Silva, Christian missionaries in Sri Lanka with a substantial Hindu minority population, reported "there were no glaring social evils associated with the indigenous religions-no sati, (...). There was thus less scope for the social reformer."[82] However, although sati was non-existent in the colonial era, earlier Muslim travellers such as Sulaiman al-Tajir reported that sati was optionally practised, which a widow could choose to undertake.[83]

Mughal Empire (1526–1857)

Ambivalence of Moghul rulers

According to Annemarie Schimmel, the Mughal Emperor Akbar (r.1556–1605) was averse to the practice of Sati; however, he expressed his admiration for "widows who wished to be cremated with their deceased husbands".[84] He was averse to abuse, and in 1582, Akbar issued an order to prevent any use of compulsion in sati.[84][85] According to M. Reza Pirbhai, a professor of South Asian and World history, it is unclear if a prohibition on sati was issued by Akbar, and other than a claim of ban by Monserrate upon his insistence, no other primary sources mention an actual ban.[86] Instances of sati continued during and after the era of Akbar.[87][88][note 9]

Jahangir (r.1605–1627), who succeeded Akbar in the early 17th century, found sati prevalent among the Hindus of Rajaur.[90][88] During this era, many Muslims and Hindus were ambivalent about the practice, with Muslim attitude leaning towards disapproval. According to Sharma, the evidence nevertheless suggests that sati was admired by Hindus, but both "Hindus and Muslims went in large numbers to witness a sati".[90] According to Reza Pirbhai, the memoirs of Jahangir suggest sati continued in his regime, was practised by Hindus and Muslims, he was fascinated by the custom, and that those Kashmiri Muslim widows who practised sati either immolated themselves or buried themselves alive with their dead husbands. Jahangir prohibited such sati and other customary practices in Kashmir.[88]

Aurangzeb issued another order in 1663, states Sheikh Muhammad Ikram, after returning from Kashmir, "in all lands under Mughal control, never again should the officials allow a woman to be burnt".[85] The Aurangzeb order, states Ikram, though mentioned in the formal histories, is recorded in the official records of Aurangzeb's time.[85] Although Aurangzeb's orders could be evaded with payment of bribes to officials, adds Ikram, later European travellers record that sati was not much practised in Mughal empire, and that Sati was "very rare, except it be some Rajah's wives, that the Indian women burn at all" by the end of Aurangzeb's reign.[85]

Descriptions by Westerners

The memoirs of European merchants and travellers, as well the colonial era Christian missionaries of British India described Sati practices under Mughal rulers.[91] Ralph Fitch noted in 1591:[92]

When the husband died his wife is burned with him, if she be alive, if she will not, her head is shaven, and then is never any account made of her after.

François Bernier (1620–1688) gave the following description:

At Lahor I saw a most beautiful young widow sacrificed, who could not, I think, have been more than twelve years of age. The poor little creature appeared more dead than alive when she approached the dreadful pit: the agony of her mind cannot be described; she trembled and wept bitterly; but three or four of the Brahmens, assisted by an old woman who held her under the arm, forced the unwilling victim toward the fatal spot, seated her on the wood, tied her hands and feet, lest she should run away, and in that situation the innocent creature was burnt alive.[93]

The Spanish missionary Domingo Navarrete wrote in 1670 of different styles of Sati during Aurangzeb's time.[94]

British and other European colonial powers

Non-British colonial powers in India

Afonso de Albuquerque banned sati immediately after the Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510.[95] Local Brahmins convinced the newly arrived Francisco Barreto to rescind the ban in 1555 in spite of protests from the local Christians and the Church authorities, but the ban was reinstated in 1560 by Constantino de Bragança with additional serious criminal penalties (including loss of property and liberty) against those encouraging the practice.[96][97]

The Dutch and the French banned it in Chinsurah and Pondichéry, their respective colonies.[98] The Danes, who held the small territories of Tranquebar and Serampore, permitted it until the 19th century.[99] The Danish strictly forbade, apparently early the custom of sati at Tranquebar, a colony they held from 1620 to 1845 (whereas Serampore (Frederiksnagore) was Danish colony merely from 1755 to 1845).[100]

Early British policy

_-_Copy.jpg.webp)

The first official British response to sati was in 1680 when the Agent of Madras Streynsham Master intervened and prohibited the burning of a Hindu widow [102][103] in Madras Presidency. Attempts to limit or ban the practice had been made by individual British officers, but without the backing of the East India Company. This is because it followed a policy of non-interference in Hindu religious affairs and there was no legislation or ban against Sati.[104] The first formal British ban was imposed in 1798, in the city of Calcutta only. The practice continued in surrounding regions. In the beginning of the 19th century, the evangelical church in Britain, and its members in India, started campaigns against sati. This activism came about during a period when British missionaries in India began focusing on promoting and establishing Christian educational systems as a distinctive contribution of theirs to the missionary enterprise as a whole.[105] Leaders of these campaigns included William Carey and William Wilberforce. These movements put pressure on the company to ban the act. William Carey, and the other missionaries at Serampore conducted in 1803–04 a census on cases of sati for a region within a 30-mile radius of Calcutta, finding more than 300 such cases there.[91] The missionaries also approached Hindu theologians, who opined that the practice was encouraged, rather than enjoined by the Hindu scriptures.[106][107]

Serampore was a Danish colony, rather than British, and the reason why Carey started his mission in Danish India, rather than in British territories, was because the East India Company did not accept Christian missionary activity within their domains. In 1813, when the Company's Charter came up for renewal William Wilberforce, drawing on the statistics on sati collected by Carey and the other Serampore missionaries and mobilising public opinion against suttee, successfully ensured the passage of a Bill in Parliament legalising missionary activities in Indias, with a view to ending the practice through the religious transformation of Indian society. He stated in his address to the House of Commons:[108]

Let us endeavour to strike our roots into the soil by the gradual introduction and establishment of our own principles and opinions; of our laws, institutions and manners; above all, as the source of every other improvement, of our religion and consequently of our morals

Elijah Hoole in his book Personal Narrative of a Mission to the South of India, from 1820 to 1828 reports an instance of Sati at Bangalore, which he did not personally witness. Another missionary, Mr. England, reports witnessing Sati in the Bangalore Civil and Military Station on 9 June 1826. However, these practices were very rare after the Government of Madras cracked down on the practice from the early 1800s (p. 82).[109][110]

The British authorities within the Bengal Presidency started systematically to collect data on the practice in 1815.

Principal reformers and 1829 ban

The principal campaigners against Sati were Christian and Hindu reformers such as William Carey and Ram Mohan Roy. In 1799 Carey, a Baptist missionary from England, first witnessed the burning of a widow on her husband's funeral pyre. Horrified by the practice, Carey and his coworkers Joshua Marshman and William Ward opposed sati from that point onward, lobbying for its abolishment. Known as the Serampore Trio, they published essays forcefully condemning the practice[20] and presented an address against Sati to then Governor General of India, Lord Wellesley.[111]

In 1812, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, founder of Brahmo Samaj, began to champion the cause of banning sati practice. He was motivated by the experience of seeing his own sister-in-law being forced to die by sati.[112] He visited Kolkata's cremation grounds to persuade widows against immolation, formed watch groups to do the same, sought the support of other elite Bengali classes, and wrote and disseminated articles to show that it was not required by Hindu scripture.[112] He was at loggerheads with Hindu groups which did not want the Government to interfere in religious practices.[113]

From 1815 to 1818 Sati deaths doubled. Ram Mohan Roy launched an attack on Sati that "aroused such anger that for awhile his life was in danger".[114] In 1821 he published a tract opposing Sati, and in 1823 the Serampore missionaries led by Carey published a book containing their earlier essays, of which the first three chapters opposed Sati. Another Christian missionary published a tract against Sati in 1927.

Sahajanand Swami, the founder of the Swaminarayan sect, preached against the practice of sati in his area of influence, that is Gujarat. He argued that the practice had no Vedic standing and only God could take a life he had given. He also opined that widows could lead lives that would eventually lead to salvation. Sir John Malcolm, the Governor of Bombay supported Sahajanand Swami in this endeavour.[115]

In 1828 Lord William Bentinck came to power as Governor of India. When he landed in Calcutta, he said that he felt "the dreadful responsibility hanging over his head in this world and the next, if... he was to consent to the continuance of this practice (sati) one moment longer."[116]

Bentinck decided to put an immediate end to Sati. Ram Mohan Roy warned Bentinck against abruptly ending Sati.[117] However, after observing that the judges in the courts were unanimously in favour of reform, Bentinck proceeded to lay the draft before his council.[118] Charles Metcalfe, the Governor's most prominent counselor expressed apprehension that the banning of Sati might be "used by the disaffected and designing" as "an engine to produce insurrection". However these concerns did not deter him from upholding the Governor's decision "in the suppression of the horrible custom by which so many lives are cruelly sacrificed."[119]

Thus on Sunday morning of 4 December 1829 Lord Bentinck issued Regulation XVII declaring Sati to be illegal and punishable in criminal courts. It was presented to William Carey for translation. His response is recorded as follows: "Springing to his feet and throwing off his black coat he cried, 'No church for me to-day... If I delay an hour to translate and publish this, many a widow's life may be sacrificed,' he said. By evening the task was finished."[120]

On 2 February 1830 this law was extended to Madras and Bombay.[121] The ban was challenged by a petition signed by "several thousand... Hindoo inhabitants of Bihar, Bengal, Orissa etc"[122] and the matter went to the Privy Council in London. Along with British supporters, Ram Mohan Roy presented counter-petitions to parliament in support of ending Sati. The Privy Council rejected the petition in 1832, and the ban on Sati was upheld.[123]

After the ban, Balochi priests in the Sindh region complained to the British Governor, Charles Napier about what they claimed was a meddlement in a sacred custom of their nation. Napier replied:

Be it so. This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs!

Thereafter, the account goes, no suttee took place.[124]

Princely states/Independent kingdoms

Sati remained legal in some princely states for a time after it had been banned in lands under British control. Baroda and other princely states of Kathiawar Agency banned the practice in 1840,[125] whereas Kolhapur followed them in 1841,[126] the princely state of Indore some time before 1843.[127] According to a speaker at the East India House in 1842, the princely states of Satara, Nagpur and Mysore had by then banned sati.[128] Jaipur banned the practice in 1846, while Hyderabad, Gwalior and Jammu and Kashmir did the same in 1847.[129] Awadh and Bhopal (both Muslim-ruled states) were actively suppressing sati by 1849.[130] Cutch outlawed it in 1852[131] with Jodhpur having banned sati about the same time.[132]

The 1846 abolition in Jaipur was regarded by many British as a catalyst for the abolition cause within Rajputana; within 4 months after Jaipur's 1846 ban, 11 of the 18 independently governed states in Rajputana had followed Jaipur's example.[133] One paper says that in the year 1846–1847 alone, 23 states in the whole of India (not just within Rajputana) had banned sati.[134][135] It was not until 1861 that Sati was legally banned in all the princely states of India, Mewar resisting for a long time before that time. The last legal case of Sati within a princely state dates from 1861 Udaipur the capital of Mewar, but as Anant S. Altekar shows, local opinion had then shifted strongly against the practice. The widows of Maharanna Sarup Singh declined to become sati upon his death, and the only one to follow him in death was a concubine.[136] Later the same year, the general ban on sati was issued by a proclamation from Queen Victoria.[137]

In some princely states such as Travancore, the custom of Sati never prevailed, although it was held in reverence by the common people. For example, the regent Gowri Parvati Bayi was asked by the British Resident if he should permit a sati to take place in 1818, but the regent urged him not to do so, since the custom of sati had never been acceptable in her domains.[138] In another state, Sawunt Waree (Sawantvadi), the king Khem Sawant III (r. 1755–1803) is credited for having issued a positive prohibition of sati over a period of ten or twelve years.[139] That prohibition from the 18th century may never have been actively enforced, or may have been ignored, since in 1843, the government in Sawunt Waree issued a new prohibition of sati.[140]

Legislative status of sati in present-day India

Following the outcry after the sati of Roop Kanwar,[141] the Indian Government enacted the Rajasthan Sati Prevention Ordinance, 1987 on 1 October 1987.[24] and later passed the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987.[31]

The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 Part I, Section 2(c) defines sati as:

The burning or burying alive of –

- (i) any widow along with the body of her deceased husband or any other relative or with any article, object or thing associated with the husband or such relative; or

- (ii) any woman along with the body of any of her relatives, irrespective of whether such burning or burying is claimed to be voluntary on the part of the widow or the women or otherwise[31]

The Prevention of Sati Act makes it illegal to support, glorify or attempt to die by sati. Support of sati, including coercing or forcing someone to die by sati, can be punished by death sentence or life imprisonment, while glorifying sati is punishable with one to seven years in prison.

Enforcement of these measures is not always consistent.[142] The National Council for Women (NCW) has suggested amendments to the law to remove some of these flaws.[143] Prohibitions of certain practices, such as worship at ancient shrines, is a matter of controversy.

Current situation

There were 30 reported cases of sati or attempted sati over a 44-year period (1943–1987) in India, the official number being 28.[144][145] A well-documented case from 1987 was that of 18-year-old Roop Kanwar.[144][146] In response to this incident, additional legislation against sati practice was passed, first within the state of Rajasthan, then nationwide by the central government of India.[31][24]

In 2002, a 65-year-old woman by the name of Kuttu died after sitting on her husband's funeral pyre in Panna district of Madhya Pradesh.[146] On 18 May 2006, Vidyawati, a 35-year-old woman allegedly committed sati by jumping into the blazing funeral pyre of her husband in Rari-Bujurg Village, Fatehpur district, Uttar Pradesh.[147]

On 21 August 2006, Janakrani, a 40-year-old woman, burned to death on the funeral pyre of her husband Prem Narayan in Sagar district; Janakrani had not been forced or prompted by anybody to commit the act.[148]

On 11 October 2008 a 75-year-old woman, Lalmati Verma, committed sati by jumping into her 80-year-old husband's funeral pyre at Checher in the Kasdol block of Chhattisgarh's Raipur district; Verma killed herself after mourners had left the cremation site.[149]

Scholars debate whether these rare reports of sati suicide by widows are related to culture or are examples of mental illness and suicide.[150] In the case of Roop Kanwar, Dinesh Bhugra states that there is a possibility that the suicides could be triggered by "a state of depersonalization as a result of severe bereavement", then adds that it is unlikely that Kanwar had mental illness and culture likely played a role.[151] However, Colucci and Lester state that none of the women reported by media to have committed sati had been given a psychiatric evaluation before their sati suicide and thus there is no objective data to ascertain if culture or mental illness was the primary driver behind their suicide.[150] Inamdar, Oberfield and Darrell state that the women who commit sati are often "childless or old and face miserable impoverished lives" which combined with great stress from the loss of the only personal support may be the cause of a widow's suicide.[152]

The Enforcement of India's 1987 Sati Law

The passing of The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 was seen as an unprecedented move to many in India, and was hailed as a new era in the Women's rights movement. Unfortunately, the enforcement of this law has been lacklustre at best.

The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 appears to be facing its greatest challenge on the aspect of the law which penalises the glorification of Sati in Section 2 of this Act:

"(i) The observance of any ceremony or the taking out of a procession in connection with the commission of Sati; or

(ii) The supporting, justifying or propagating of the practice of Sati in any manner; or

(iii) The arranging of any function to eulogise the person who has committed Sati; or

(iv) The creation of a trust, or the collection of funds, or the construction of a temple or other structure or the carrying on of any form of worship or the performance of any ceremony thereat, with a view to perpetuate the honour of, or to preserve the memory of, a person who has committed Sati."[4]

The punishment for glorifying sati is a minimum one-year sentence that can be increased to seven years in prison and a minimum fine of 5,000 rupees that can be increased to 30,000 rupees.[153] This Section of the Act has become heavily criticised by both sides of the Sati debate. Proponents of Sati argue against it, claiming the practice to be a part of Indian culture.[27] Simultaneously, those against the practice of Sati also question the practicality of such a law, since it may be interpreted in a manner so as to punish the victim.[29] Enforcement aside, the existence of the law is debated as well.

The nation continues to witness a cultural divide in regards to their opinions of Sati, with a great deal of the glorification of this practice occurring within it. The Calcutta Marwari have been noted to follow the practice of Sati worship, yet the community alleges it to be a part of their culture and insist they be permitted to follow their practices.[28] Additionally, the practice is still fervently revered in parts of rural India, with entire temples still dedicated to previous victims of Sati.[36]

India is steeped in a heavily patriarchal system and their norms, making it difficult for even the most vigilant of authorities to enforce the 1987 Act. An instance of this can be seen in 2002 where two police officers were attacked by a mob of approximately 1000 people when attempting to stop an instance of Sati.[37] In India, the powers of the police remain structurally limited by the political elite.[30] Their limited powers are compounded by "patriarchal values, religious freedoms, and ideologies"[41] within India.

Furthermore, enforcement of this law is easily circumnavigated by authorities by writing off cases of Sati as acts of suicide.[35] This is attributed to not only a hesitancy to prosecute when the punishment remains so severe, but also another indication of a deeply patriarchal society.

Practice

Accounts describe numerous variants in the sati ritual. The majority of accounts describe the woman seated or lying down on the funeral pyre beside her dead husband. Many other accounts describe women walking or jumping into the flames after the fire had been lit,[154] and some describe women seating themselves on the funeral pyre and then lighting it themselves.[155]

Variations in procedure

Although sati is typically thought of as consisting of the procedure in which the widow is placed, or enters, or jumps, upon the funeral pyre of her husband, slight variations in funeral practice have been reported here as well, by region. For example, the mid-17th-century traveller Tavernier claims that in some regions, the sati occurred by construction of a small hut, within which the widow and her husband were burnt, while in other regions, a pit was dug, in which the husband's corpse was placed along with flammable materials, into which the widow jumped after the fire had started.[156] In mid-nineteenth-century Lombok, an island in today's Indonesia, the local Balinese aristocracy practised widow suicide on occasion; but only widows of royal descent could burn themselves alive (others were stabbed to death by a kris knife first). At Lombok, a high bamboo platform was erected in front of the fire and, when the flames were at their strongest, the widow climbed up the platform and dived into the fire.[157]

Live burials

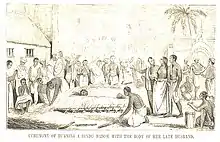

Most Hindu communities, especially in North India, only bury the bodies of those under the age of two, such as baby girls. Those older than two are customarily cremated.[158] A few European accounts provide rare descriptions of Indian sati that included the burial of the widow with her dead husband.[1] One of the drawings in the Portuguese Códice Casanatense shows the live burial of a Hindu widow in the 16th century.[159] Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a 17th-century world traveller and trader of gems, wrote that women were buried with their dead husbands along the Coast of Coromandel while people danced during the cremation rites.[160]

The 18th-century Flemish painter Frans Balthazar Solvyns provided the only known eyewitness account of an Indian sati involving a burial.[161] Solvyns states that the custom included the woman shaving her head, music and the event was guarded by East India Company soldiers. He expressed admiration for the Hindu woman, but also calls the custom barbaric.[161]

The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 Part I, Section 2(c) includes within its definition of sati not just the act of burning a widow alive, but also that of burying her alive.[31]

Compulsion

Sati is often described as voluntary, although in some cases it may have been forced. In one narrative account in 1785, the widow appears to have been drugged either with bhang or opium and was tied to the pyre which would have prevented her from escaping the fire, if she changed her mind.[162]

The Anglo-Indian press of the period proffered several accounts of alleged forcing of the woman. As an example, The Calcutta Review published accounts as the following one:

In 1822, the Salt Agent at Barripore, 16 miles south of Calcutta, went out of his way to report a case which he had witnessed, in which the woman was forcibly held down by a great bamboo by two men, so as to preclude all chance of escape. In Cuttack, a woman dropt herself into a burning pit, and rose up again as if to escape, when a washerman gave her a push with a bamboo, which sent her back into the hottest part of the fire.[163] This is said to be based on the set of official documents.[164] Yet another such case appearing in official papers, transmitted into British journals, is case 41, page 411 here, where the woman was, apparently, thrown twice back in the fire by her relatives, in a case from 1821.[165]

Apart from accounts of direct compulsion, some evidence exists that precautions, at times, were taken so that the widow could not escape the flames once they were lit. Anant S. Altekar, for example, points out that it is much more difficult to escape a fiery pit that one has jumped in, than descending from a pyre one has entered on. He mentions the custom of the fiery pit as particularly prevalent in the Deccan and western India. From Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, where the widow typically was placed in a hut along with her husband, her leg was tied to one of the hut's pillars. Finally, from Bengal, where the tradition of the pyre held sway, the widow's feet could be tied to posts fixed to the ground, she was asked three times if she wished to ascend to heaven, before the flames were lit.[166]

The historian Anant Sadashiv Altekar states that some historical records suggest without doubt that instances of sati were forced, but overall the evidence suggests most instances were a voluntary act on the woman's part.[167]

Symbolic sati

There have been accounts of symbolic sati in some Hindu communities. A widow lies down next to her dead husband, and certain parts of both the marriage ceremony and the funeral ceremonies are enacted, but without her death. An example in Sri Lanka is attested from modern times.[168] Although this form of symbolic sati has contemporary evidence, it should by no means be regarded as a modern invention. For example, the ancient and sacred Atharvaveda, one of the four Vedas, believed to have been composed around 1000 BCE, describes a funerary ritual where the widow lies down by her deceased husband, but is then asked to ascend, to enjoy the blessings from the children and wealth left to her.[169]

In 20th-century India, a tradition developed of venerating jivit (living satis). A jivit is a woman who once desired to commit sati, but lives after having sacrificed her desire to die.[170] Two famous jivit were Bala Satimata, and Umca Satimata, both lived until the early 1990s.[171]

Prevalence

Records of sati exist across the subcontinent. However, there seems to have been major differences in different regions, and among communities. No reliable figures exist for the numbers who have died by sati in general.

Numbers

An 1829 report by a Christian missionary organisation includes among other things, statistics on sati. It begins with a declaration that "the object of all missions to the heathen is to substitute for these systems the Gospel of Christ", thereafter lists sati for each year over the period 1815–1824, which totals 5,369, followed by a statement that a total of 5,997 instances of women were burned or buried alive in the Bengal presidency over a 10-year period, i.e., average 600 per year. In the same report, it states that the Madras and Bombay presidencies totalled 635 instances of sati over the same ten-year period.[172] The 1829 missionary report does not provide its sources and acknowledges that "no correct idea can be formed of the number of murders occasioned by suttees", then states that some of the statistics are based on "conjectures".[172] According to Yang, these "numbers are fraught with problems".[173]

William Bentinck, in an 1829 report, without specifying the year or period, stated that "of the 463 satis occurring in the whole of the Presidency of Fort William,[note 10] 420 took place in Bengal, Behar, and Orissa, or what is termed the Lower Provinces, and of these latter 287 in the Calcutta Division alone". For the Upper Provinces, Bentinck added, "in these Provinces the satis amount to forty three only upon a population of nearly twenty millions", i.e., average one sati per 465,000.[174]

Social composition and age distribution

Anand Yang, speaking of the early nineteenth century, says that contrary to conventional wisdom, sati was not, in general, an upper class phenomenon, but spread through the classes/castes. In the 575 reported cases from 1823, for example, 41 percent were Brahmins, 6 percent were Kshatriyas, 2 percent were Vaishiyas, and 51 percent were Sudras. In Banaras, in the 1815–1828 British records, the upper castes were only represented for 2 years - less than 70% of the total; whereas in 1821, all sati were from the upper castes there.

Yang notes that many studies seem to emphasise the young age of the widows who committed sati. By studying the British figures from 1815 to 1828, Yang states that the overwhelming majority were ageing women; statistics from 1825 to 1826 show that about two thirds were above the age of 40 when committing sati.[175]

Regional variations of incidence

Anand Yang summarizes the regional variation in incidence of sati as follows:

..the practice was never generalized..but was confined to certain areas: in the north,..the Gangetic Valley, Punjab and Rajasthan; in the west, to the southern Konkan region; and in the south, to Madurai and Vijayanagara.[51]

Konkan/Maharashtra

Narayan H. Kulkarnee believes that sati came to be practised in medieval Maharashtra, initially by the Maratha nobility claiming Rajput descent. According to Kulkarnee, the practice may have increased across caste distinctions as an honour-saving custom in the face of Muslim advances into the territory. But the practice never gained the prevalence seen in Rajasthan or Bengal, and social customs of actively dissuading a widow from committing sati are well established. Apparently not a single instance of forced sati is attested for the 17th and 18th centuries CE.[176] Forced or not forced, there were several instances of women from the Bhosale family committing sati. One was Shivaji's eldest childless widow, Putalabai, who committied sati after her husband's death. One controversial case was that of Chhatrapati Shahu's widow who was forced to commit sati due to political intrigues regarding succession at the Satara court following Shahu's death in 1749. The most "celebrated" case of sati was that of Ramabai, the widow of Brahmin Peshwa Madhavrao I, who committed sati in 1772 on her husband's funeral pyre.This was considered unusual because unlike "kshatriya" widows, Brahmin widows very rarely followed the practice.[177]

South India

Several sati stones have been found in Vijayanagar empire. These stones were erected as a mark of a heroic deed of sacrifice of the wife for her husband and towards the land.[178] The sati stone evidence from the time of the empire is regarded as relatively rare; only about 50 are clearly identified as such. Thus, Carla M. Sinopoli, citing Verghese, says that despite the attention European travellers paid the phenomenon, it should be regarded as having been fairly uncommon during the time of the Vijayanagara empire.[179]

The Madurai Nayak dynasty (1529–1736 CE) seems to have adopted the custom in larger measure, one Jesuit priest in 1609 in Madurai observed the burning of 400 women at the death of Nayak Muttu Krishnappa.[180]

The Kongu Nadu region of Tamil Nadu has the highest number of Veera Maha Sati (வீரமாசதி) or Veeramathy temples (வீரமாத்தி) from all the native Kongu castes.[181]

A few records exist from the Princely State of Mysore, established in 1799, that say permission to commit sati could be granted. Dewan (prime minister) Purnaiah is said to have allowed it for a Brahmin widow in 1805,[182] whereas an 1827 eye witness to the burning of a widow in Bangalore in 1827 says it was rather uncommon there.[183]

Gangetic plain

In the Upper Gangetic plain, while sati occurred, there is no indication that it was especially widespread. The earliest known attempt by a government - the Muslim Sultan Muhammad ibn Tughluq - to stop this Hindu practice took place in the Delhi Sultanate in the 14th century.[184]

In the Lower Gangetic plain, sati practice may have reached a high level fairly late in history. According to available evidence and existing reports of occurrences, the greatest incidence of sati in any region and period occurred in Bengal and Bihar in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[185]

Nepal and Bali

The earliest stone inscription in the Indian subcontinent relating to sati has been found in Nepal, dating from the 5th century, where the king successfully persuades his mother not to commit sati after his father dies,[186] suggesting that it was practised but was not compulsory.[187] Nepal formally banned sati in 1920.[188]

On the Indonesian island of Bali, sati (known as masatya) was practised by the aristocracy as late as 1903, until the Dutch colonial authorities pushed for its termination, forcing the local Balinese princes to sign treaties containing the prohibition of sati as one of the clauses.[189] Early Dutch observers of the Balinese custom in the 17th century said that only widows of royal blood were allowed to be burned alive. Concubines or others of inferior blood lines who consented or wanted to die with their princely husband had to be stabbed to death before being burned.[190]

Terminology

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Lindsey Harlan,[191] having conducted extensive field work among Rajput women, has constructed a model of how and why women who committed sati are still venerated today, and how the worshippers think about the process involved.[192] Essentially, a woman becomes a sati in three stages:

- having been a pativrata, or dutiful wife, during her husband's life,

- making, at her husband's death, a solemn vow to burn by his side, thus gaining status as a sativrata, and

- having endured being burnt alive, achieving the status of satimata.

Pativrata

The pativrata is devoted and subservient to her husband, and also protective of him. If he dies before her, some culpability is attached to her for his death, as not having been sufficiently protective of him. Making the vow to burn alive beside him removes her culpability, as well as enabling her to protect him from new dangers in the afterlife.

Sativrata

In Harlan's model, having made the holy vow to burn herself, the woman becomes a sativrata, existing in a transitional stage between the living and the dead called the Antarabhava before ascending the funeral pyre. Once a woman had committed herself to becoming a sati, popular belief thought her to be endowed with many supernatural powers. Lourens P. Van Den Bosch enumerates some of them: prophecy and clairvoyance, and the ability to bless with sons women who had not borne sons before. Gifts from a sati were venerated as valuable relics, and in her journey to the pyre, people would seek to touch her garments to benefit from her powers.[193]

Lindsey Harlan probes deeper into the sativrata state. As a transitional figure on her path to becoming a powerful family protector as satimata, the sativrata dictates the terms and obligations that the family, in showing reverence to her, must observe in order for her to be able to protect them once she has become satimata. These conditions are generally called ok. A typical example of an ok is a restriction on the colours or types of clothing the family members may wear.

Shrap, or curses, are also within the sativrata's power, associated with remonstrations on members of the family for how they have failed. One woman cursed her in-laws when they brought neither a horse nor a drummer to her pyre, saying that whenever they might need either in the future, (many religious rituals require the presence of such things), it would not be available to them.

Satimata

After her death on the pyre, the woman is finally transformed into the shape of the satimata, a spiritual embodiment of goodness, her principal concern being a family protector. Typically, the satimata manifests in the dreams of family members, for example, to teach the women how to be good pativratas, having proved herself through her sacrifice that she was the perfect pativrata. However, although the satimata's intentions are always for the good of the family, she is not averse to letting children become sick, or the cows' udders to wither, if she thinks this is an appropriate lesson to the living wife who has neglected her duties as pativrata.

In scriptures

David Brick, in his 2010 review of ancient Indian literature, states[194]

There is no mention of sahagamana (sati) whatsoever in either Vedic literature or any of the early Dharmasutras or Dharmasastras. By "early Dharmasutras or Dharmasastras", I refer specifically to both the early Dharmasutras of Apastamba, Hiranyakesin, Gautama, Baudhayana and Vasistha, and the later Dharmasastras of Manu, Narada, and Yajnavalkya. – David Brick, Yale University[194]

The earliest scholarly discussion of sati is found in Sanskrit literature dated to 10th- to 12th-century.[195] The earliest known commentary on sati by Medhatithi of Kashmir argues that it is a form of suicide, which is prohibited by the Vedic tradition.[194] Vijnanesvara, of the 12th-century Chalukya court, and the 13th-century Madhvacharya, argue that sati should not to be considered suicide, which was otherwise variously banned or discouraged in the scriptures.[196] They offer a combination of reasons, both in for and against sati.[197]

In the Hindu scriptures, states David Brick, Sati is a wholly voluntary endeavor; it is not portrayed as an obligatory practice, nor does the application of physical coercion serve as a motivating factor in its lawful execution.[198]

In the following, a historical chronology is given of the debate within Hinduism on the topic of sati.

The oldest Vedic texts

The most ancient texts still revered among Hindus today are the Vedas, where the Saṃhitās are the most ancient, four collections roughly dated in their composition to 1700–1100 BCE. In two of these collections, the Rigveda and the Atharvaveda, many verses share relevance to the idea of sati.

Claims about the mention of sati in Rig Veda vary. There are differing interpretations of one of the passages, which reads:

- इमा नारीरविधवाः सुपत्नीराञ्जनेन सर्पिषा संविशन्तु |

- अनश्रवो.अनमीवाः सुरत्ना आ रोहन्तु जनयोयोनिमग्रे || (RV 10.18.7)

This passage and especially the last of these words has been interpreted in different ways, as can be seen from various English translations:

- May these women, who are not widows, who have good husbands, who are mothers, enter with unguents and clarified butter:

- without tears, without sorrow, let them first go up into the dwelling.[199] (Wilson, 1856)

- Let these women, whose husbands are worthy and are living, enter the house with ghee (applied) as collyrium (to their eyes).

- Let these wives first step into the pyre, tearless without any affliction and well adorned.[200] (Kane, 1941)

Verse 7 itself, unlike verse 8, does not mention widowhood, but the meaning of the syllables yoni (literally "seat, abode") have been rendered as "go up into the dwelling" (by Wilson), as "step into the pyre" (by Kane), as "mount the womb" (by Jamison/Brereton)[201] and as "go up to where he lieth" (by Griffith).[202] A reason given for the discrepancy in translation and interpretation of verse 10.18.7, is that one consonant in a word that meant house, yonim agree ("foremost to the yoni"), was deliberately changed to a word that meant fire, yomiagne,[203] by those who wished to claim scriptural justification.

In addition, the following verse, which is unambiguously about widows, contradicts any suggestion of the woman's death; it explicitly states that the widow should return to her house.

- उदीर्ष्व नार्यभि जीवलोकं गतासुमेतमुप शेष एहि |

- हस्तग्राभस्य दिधिषोस्तवेदं पत्युर्जनित्वमभि सम्बभूथ || (RV 10.18.8)

- Rise, come unto the world of life, O woman — come, he is lifeless by whose side thou liest. Wifehood with this thy husband was thy portion, who took thy hand and wooed thee as a lover.

Dehejia states that Vedic literature has no mention of any practice resembling sati.[204] There is only one mention in the Vedas, of a widow lying down beside her dead husband who is asked to leave the grieving and return to the living, then prayer is offered for a happy life for her with children and wealth. Dehejia writes that this passage does not imply a pre-existing sati custom, nor of widow remarriage, nor that it is authentic verse; its solitary mention may also be explained as an insertion into the text at a latter date.[204][note 11] Dehejia writes that no ancient or early medieval era Buddhist texts mention sati (since killing/self killing) would have been condemned by them.[204]

Absence in religious texts

David Brick, a professor of South Asian Studies, states that neither sati nor equivalent terms such as sahagamana are ever mentioned in any Vedic literature (Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads), or in any of the early Dharmasutras or Dharmasastras.[194]

The Brahmana literature, one of the layers within the ancient Vedic texts, dated about 1000 BCE – 500 BCE is entirely silent about sati, according to the historian Altekar. Similarly, the Grhyasutras, a body of texts devoted to ritual, composed at about the same time as the most recent Brahmana literature, sati is not mentioned either. What is mentioned concerning funeral rites, is that the widow is to be brought back from her husband's funeral pyre, either by his brother, or by a trusted servant. In the Taittiriya Aranyaka from about the same time, it is said that when leaving, the widow takes from her husband's side such objects as his bow, gold and jewels, and hope is expressed that the widow and her relatives lead a happy and prosperous life afterwards. According to Altekar, it is "clear" that the custom of actual widow burning had died out a long time previously.[205]

Nor is the practice of sati mentioned anywhere in the Dharmasutras,[206] texts tentatively dated by Pandurang Vaman Kane to 600–100 BCE, while Patrick Olivelle thinks the parameters should be roughly 250–100 BCE.[207]

Not only is sati not mentioned in Brahmana and early Dharmasastra literature, Satapatha Brahmana explains that suicide/self-murder by anyone is inappropriate (adharmic). This Śruti prohibition became one of the several bases for arguments presented against sati by 11th- to 14th-century Hindu scholars such as Medhatithi of Kashmir,[194]

- Therefore, one should not depart before one's natural lifespan. – Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa, 10.2.6.7[194]

Thus, in none of the principal religious texts believed to be composed before the Common Era is there any evidence for the sanctioning of the practice of sati; it is wholly unmentioned. However, the archaic Atharvaveda does contain hints of a funeral practice of symbolic sati. Also, in the twelfth-century CE commentary of Apararka, claiming to quote the Dharmasutra text Apastamba, it says that if a widow has made a vow of burning herself (anvahorana, "ascend the pyre"), but then retracts her vow, she must expiate her sin by the penance ritual called Prajapatya-vrata[208]

Justifications for the practice are given in the Vishnu Smriti, dated 6th-9th century CE by Patrick Olivelle:

- When a woman's husband has died, she should either practice ascetic celibacy or ascend (the funeral pyre) after him. — Vishnu Smriti, 25.14[194]

Valmiki Ramayana

The oldest portion of the epic Ramayana, the Valmiki Ramayana, is tentatively dated for its composition by Robert P. Goldman to 750–500 BCE.[209] Anant S. Altekar says that no instances of sati occur in this earliest part of the Ramayana.[210]

According to Ramashraya Sharma, there is no conclusive evidence of the sati practice in the Ramayana. For instance, Tara, Mandodari and the widows of Ravana, all live after their respective husband's deaths, though all of them announce their wish to die, while lamenting for their husbands. The first two remarry their brother-in-law. He also mentions that though Dashratha, father of Rama, died soon after his departure from the city, his mothers survived and received him after the completion of his exile. The only instance of sati appears in the Uttara Kanda – believed to be a later addition to the original text – in which Kushadhwaja's wife performs sati.[211] The Telugu adaptation of the Ramayana, the 14th-century Ranganatha Ramayana, tells that Sulochana, wife of Indrajit, became sati on his funeral pyre.[212]

Mahabharata

Instances of sati are found in the Mahabharata.

Madri, the second wife of Pandu, immolates herself. She believes she is responsible for his death, as he had been cursed with death if he ever had intercourse. He died while performing the forbidden act with Madri; she blamed herself for not rejecting him, as she knew of the curse. Also, in the case of Madri the entire assembly of sages sought to dissuade her from the act, and no religious merit is attached to the fate she chooses against all advice. In contrast, Kunti, the first wife of Pandu and the leading female character of Mahabharata, suffered several ordeals along with her sons, the Pandavas, and lived to see the end of the Mahabharata war. In the Musala-parvan of the Mahabharata, the four wives of Vasudeva are said to commit sati. Furthermore, as news of Krishna's death reaches Hastinapur, five of his wives ascended the funeral pyre.[213]

Against these stray examples within the Mahabharata of sati, there are scores of instances in the same epic of widows who do not commit sati, and none are blamed for not doing so.[214]

Principal Smrtis, c. 200 BCE–1200 CE

_in_Kedareshvara_temple_at_Balligavi.JPG.webp)

The four works, Manusmṛti (200 BCE–200 CE), Yājñavalkya Smṛti (200–500 CE), Nāradasmṛti (100 BCE–400 CE) and the Viṣṇusmṛti (700–1000 CE) are the principal Smrti works in the Dharmaśāstra tradition, along with the Parasara Smrti, composed in the latter period, rather than in the earlier.

The first three principal smrtis, those of Manu, Yājñavalkya and Nārada, do not contain any mention of sati.[194]

Emergence of debate on sati, 700–1200 CE

Moriz Winternitz states that Brihaspati Smriti prohibits burning of widows.[215] Brihaspati Smriti was written after the three principal smritis of Manu, Yājñavalkya and Nārada.[215]

A passage of the Parasara Smriti says:

- If a woman adheres to a vow of ascetic celibacy (brahmacarya) after her husband has died, then when she dies, she obtains heaven, just like those who were celibate. Further, three and a half krores or however many hairs are on a human body – for that long a time (in years) a woman who follows her husband (in death) shall dwell in heaven. — Parasara Smriti, 4.29–31[194]

Neither of these suggest that sati as mandatory, but the Parasara Smriti elaborates the benefits of sati in greater detail.[194]

Within the dharmashastric tradition espousing sati as a justified or even recommended option to ascetic widowhood, there remains a curious conception worth noting - the after-death status of a woman committing sati. Burning herself on the pyre would give her and her husband, automatic, but not eternal, reception into heaven (svarga), whereas only the wholly chaste widow living out her natural lifespan could hope for final liberation (moksha) and the breaking the cycle of samsaric rebirth.

While some smriti passages allow sati as optional, others forbid the practice entirely. Vijñāneśvara (c. 1076–1127), an early Dharmaśāstric scholar, claims that many smriti call for the prohibition of sati among Brahmin widows, but not among other social castes. Vijñāneśvara, quoting scriptures from Paithinasi and Angiras to support his argument, states:

- Due to Vedic injunction, a Brahmin woman should not follow her husband in death, but for the other social classes, tradition holds this to be the supreme Law of Women... when a woman of Brahmin caste follows her husband in death, by killing herself she leaders neither herself nor her husband to heaven.[194]

However, as proof of the contradictory opinion of the smriti on sati, in his Mitākṣarā, Vijñāneśvara argues Brahmin women are technically only forbidden from performing sati on pyres other than those of their deceased husbands.[194] Quoting the Yājñavalkya Smṛti, Vijñāneśvara states, "a Brahmin woman ought not to depart by ascending a separate pyre." David Brick states that the Brahmin sati commentary suggests that the practice may have originated in the warrior and ruling class of medieval Indian society.[194] In addition to providing arguments in support of sati, Vijñāneśvara offers arguments against the ritual.

However, those who supported the ritual did put restrictions on sati. It was considered wrong for women who had young children to care for and those who were pregnant or menstruating. A woman who had doubts or did not wish to commit sati at the last moment could be removed from the pyre by a man, usually a brother of the deceased or someone from her husband's side of the family.[194]

David Brick,[194] summarizing the historical evolution of scholarly debate on sati in medieval India, states:

To summarize, one can loosely arrange Dharmasastic writings on sahagamana into three historical periods. In the first of these, which roughly corresponds to the second half of the 1st millennium CE, smrti texts that prescribe sahagamana begin to appear. However, during approximately this same period, other Brahmanical authors also compose a number of smrtis that proscribe this practice specifically in the case of Brahmin widows. Moreover, Medhatithi – our earliest commentator to address the issue – strongly opposes the practice for all women. Taken together, this textual evidence suggests that sahagamana was still quite controversial at this time. In the following period, opposition to this custom starts to weaken, as none of the later commentators fully endorses Medhatithi's position on sahagamana. Indeed, after Vijnanesvara in the early twelfth century, the strongest position taken against sahagamana appears to be that it is an inferior option to brahmacarya (ascetic celibacy), since its result is only heaven rather than moksa (liberation). Finally, in the third period, several commentators refute even this attenuated objection to sahagamana, for they cite a previously unquoted smrti passage that specifically lists liberation as a result of the rite's performance. They thereby claim that sahagamana is at least as beneficial an option for widows as brahmacarya and perhaps even more so, given the special praise it sometimes receives. These authors, however, consistently stop short of making it an obligatory act. Hence, the commentarial literature of the dharma tradition attests to a gradual shift from strict prohibition to complete endorsement in its attitude toward sahagamana.[194]

Legend of goddess Sati

Although the myth of the goddess Sati is that of a wife who dies by her own volition on a fire, this is not a case of the practice of sati. The goddess was not widowed, and the myth is quite unconnected with the justifications for the practice.

Justifications for involuntary sati

Julia Leslie points to Strī-dharma-paddhati, an 18th-century CE text on the duties of the wife by Tryambakayajvan that contains statements she regards as evidence for a sub-tradition that justifies strongly encouraged, pressured, or even forced sati; however the standard view of sati within the justifying tradition is that of the woman who out of moral heroism chooses sati, rather than choosing to enter ascetic widowhood.[6][note 12] Tryambaka is quite clear upon the automatic good effect of sati for the woman who was a 'bad' wife:

Women who, due to their wicked minds, have always despised their husbands [...] whether they do this (i.e., sati), of their own free will, or out of anger, or even out of fear – all of them are purified from sin.

Thus, as Leslie puts it, becoming (or being pressured into the role of) a sati was, within Tryambaka's thinking, the only truly effective method of atonement for the bad wife.

Exegesis scholarship against sati

Opposition to sati was expressed by several exegesis scholars: the ninth- or tenth-century Kashmir scholar Medatithi – who offers the earliest known explicit discussion of sati,[194] the 12th- to 17th-century scholars Vijnanesvara, Apararka and Devanadhatta, as well as the mystical Tantric tradition, with its valorisation of the feminine principle.

Explicit criticisms were published by Medhatithi, a commentator on various theological works.[216] He offered two arguments for his opposition. He considered sati a form of suicide, which was forbidden by the Vedas: "One shall not die before the span of one's life is run out."[216] Medhatithi offered a second reason against sati, calling it against dharma (adharma). He argued that there is a general prohibition against violence of any form against living beings, especially killing, in the Vedic dharma tradition. Sati causes death, which is self-violence; thus sati is against Vedic teachings.[217]

Vijnanesvara presents both sides of the argument for and against sati. First, he argues that Vedas do not prohibit sacrifice aimed to stop an enemy, or in pursuit of heaven; thus sati for these reasons is not prohibited. Then he presents two arguments against sati, calling it "objectionable". The first is based on hymn 10.2.6.7 of Satapatha, Brahmana will forbids suicide. His second reason against sati is an appeal to the relative merit between two choices. Death may grant a woman's wish to enter heaven with her dead husband, but living offers her the possibility of reaching moksha through knowledge of the self through learning, reflecting and meditating. In Vedic tradition, moksha is of higher merit than heaven, because moksha leads to eternal, unsurpassed bliss while heaven is impermanent, thus a smaller happiness. Living gives a widow the option to discover a deeper and totally fulfilling happiness than dying through sati does.[197]

Apararka acknowledges that Vedic scripture prohibits violence against living beings and "one should not kill", however, he argues that this rule prohibits violence against another person, but does not prohibit killing oneself. Thus sati is a woman's choice and it is not prohibited by Vedic tradition.[218]

Counter-arguments within Hinduism

Reform and bhakti movements within Hinduism favoured egalitarian societies, and in line with the tenor of these beliefs, generally condemned the practice, sometimes explicitly. The 12th-century Virashaiva movement condemned the practice.[219] Later, Sahajananda Swami, the founder of Vaishnavite Swaminarayana sampradaya preached against sati in the 18th century in western India.

In a petition to the East India Company in 1818, Ram Mohan Roy wrote that: "All these instances are murders according to every shastra."[220]

In culture

European artists in the eighteenth century produced many images for their own native markets, showing widows as heroic women and moral exemplars.[221]

In Jules Verne's novel Around the World in Eighty Days, Phileas Fogg rescues Princess Aouda from forced sati.[222]

In her article "Can the Subaltern Speak?", Indian philosopher Gayatri Spivak discussed the history of sati during the colonial era[223] and how the practise took the form of trapping women in India in a double bind of either self-expression attributed to mental illness and social rejection, or of self-incrimination according to colonial legislation.[224] The woman who commits sati takes the form of the subaltern in Spivak's work, a form that much of postcolonial studies take very seriously.

The 2005 novel The Ashram by Indian writer Sattar Memon, deals with the plight of an oppressed young woman in India, under pressure to commit sati and the endeavours of a western spiritual aspirant to save her.

In Krishna Dharabasi's Nepali novel Jhola, a young widow narrowly escapes self immolation. The novel was later adapted into a movie titled after the book.[225]

Amitav Ghosh's Sea of Poppies (2008) represents the practice of sati in Gazipur city in the state of Uttar Pradesh and reflects the feelings and experience of a young woman named 'Deeti' who escaped the sati that her family and relatives were trying to force her to do after her old husband died.

Rudyard Kipling's poem The Last Suttee (1889) recounts how the widowed queen of a Rajput ruler disguised herself as a nautch girl in order to pass through a line of guards and die upon his pyre.[226]

Notes

- The spelling suttee is a phonetic spelling using 19th-century English orthography. The satī transliteration uses the more modern ISO/IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration), the academic standard for writing the Sanskrit language with the Latin alphabet system.[1]

- "The legal rights, as well as the ideal images, of women were increasingly circumscribed during the Gupta era. The Laws of Manu, compiled from about 200 to 400 C.E., came to be the most prominent evidence that this era was not necessarily a golden age for women. Through a combination of legal injunctions and moral prescriptions, women were firmly tied to the patriarchal family, ... Thus the Laws of Manu severely reduced the property rights of women, recommended a significant difference in ages between husband and wife and the relatively early marriage of women, and banned widow remarriage. Manu's preoccupation with chastity reflected possibly a growing concern for the maintenance of inheritance rights in the male line, a fear of women undermining the increasingly rigid caste divisions, and a growing emphasis on male asceticism as a higher spiritual calling."[7]

- "Therefore, by the time of the Mauryan Empire the position of women in mainstream Indo-Aryan society seems to have deteriorated. Customs such as child marriage and dowry were becoming entrenched; and a young women's purpose in life was to provide sons for the male lineage into which she married. To quote the Arthashāstra: 'wives are there for having sons'. Practices such as female infanticide and the neglect of young girls were also developing at this time. Further, due to the increasingly hierarchical nature of the society, marriage was becoming a mere institution for childbearing and the formalization of relationships between groups. In turn, this may have contributed to the growth of increasingly instrumental attitudes towards women and girls (who moved home at marriage). It is important to note that, in all likelihood, these developments did not affect people living in large parts of the subcontinent—such as those in the south, and tribal communities inhabiting the forested hill and plateau areas of Southern Asia where hindiusm was practised. That said, these deleterious features have continued to blight Indo-Aryan-speaking areas of the subcontinent until the present day.[8]

- "Darkness can be said to have pervaded one aspect of society during the inter-imperial centuries: the degradation of women. In Hinduism, the monastic tradition was not institutionalized as it was in the heterodoxies of Buddhism and Jainism, where it was considered the only true path to spiritual liberation. (p. 88) Instead, Hindu men of upper castes, passed through several stages of life: that of initiate, when those of the twice-born castes received the sacred thread; that of student, when the upper castes studied the Vedas; that of the married man, when they became householders; ... Since the Hindu man was enjoined to take a wife at the appropriate period of life, the roles and nature of women presented some difficulty. Unlike the monastic ascetic, the Hindu man was exhorted to have sons, and could not altogether avoid either women or sexuality. ... Manu approved of child brides, considering a girl of eight suitable for a man of twenty-four, and one of twelve appropriate for a man of thirty.(p. 89) If there was no dowry, or if the groom's family paid that of the bride, the marriage was ranked lower. In this ranking lay the seeds of the curse of dowry that has become a major social problem in modern India, among all castes, classes and even religions. (p. 90) ... the widow's head was shaved, she was expected to sleep on the ground, eat one meal a day, do the most menial tasks, wear only the plainest, meanest garments, and no ornaments. She was excluded from all festivals and celebrations since she was considered inauspicious to all but her own children. This penitential life was enjoined because the widow could never quite escape the suspicion that she was in some way responsible for her husband's premature demise. ... The positions taken and the practices discussed by Manu and the other commentators and writers of Dharmashastra are not quaint relics of the distant past, but alive and recurrent in India today – as the attempts to revive the custom of sati (widow immolation) in recent decades has shown."[10]