Zephyrus

In Greek mythology and religion, Zephyrus (Ancient Greek: Ζέφυρος, romanized: Zéphuros, lit. 'westerly wind') also spelled in English as Zephyr is the god and personification of the West wind, one of the several wind gods, the Anemoi. The son of Eos, the goddess of the dawn, and Astraeus, Zephyrus is the most gentle and favourable of the winds, and is also associated with flowers, springtime and even procreation.[1] In myths, he is presented as the tender breeze, and he is known for his unrequited love for the Spartan prince Hyacinthus. Although he along with Boreas are the two most prominent wind gods, their role in mythology is relatively limited.[2]

| Zephyrus | |

|---|---|

God of the West Wind | |

Zephyrus on an antique fresco in Pompeii | |

| Greek | Ζέφυρος |

| Abode | Sky |

| Animals | Horse, swan |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Eos and Astraeus |

| Siblings | Winds (Boreas, Eurus, and Notus), Stars (Eosphorus/Hesperus, Pyroeis, Stilbon, Phaethon, and Phaenon), Memnon, Emathion, Astraea |

| Consort | Iris or Flora |

| Children | Pothos, Balius and Xanthus, Carpus, tigers |

| Equivalents | |

| Roman equivalent | Favonius |

Zephyrus, similarly to his brothers, also received a minor cult during ancient times, although his worship was fairly minor compared to others and he was overshadowed by the more important gods such as the Twelve Olympians. Nevertheless, traces of it are found in Classical Athens and surrounding regions and city-states, where it was usually joint with the cults of the other wind gods.

His equivalent in Roman mythology and religion is the god Favonius.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Greek religion |

|---|

|

Etymology

The ancient Greek noun ζέφυρος is the word for the wind that blows from the west.[3] His name is attested in Mycenaean Greek as ze-pu2-ro (Linear B: 𐀽𐁆𐀫),[4] which points to a possible Proto-Hellenic form *Dzépʰuros.[5] Further attestation of the god and his worship as part of the Anemoi is found in the word-forms 𐀀𐀚𐀗𐀂𐀋𐀩𐀊, a-ne-mo-i-je-re-ja, 𐀀𐀚𐀗𐄀𐀂𐀋𐀩𐀊, a-ne-mo i-je-re-ja, that is, "priestess of the winds", found on the KN Fp 1 and KN Fp 13 tablets.[6][7]

Traditionally, 'Zephyros' has been linked to the word ζόφος (zóphos) meaning "darkness" or "west". Both in turn have been connected to the Proto-Indo-European root *(h₃)yebʰ-, meaning "to enter, to penetrate" (from which οἴφω (oíphō), meaning 'to have sex', also derives).[8] It has been noted however that a development *Hi̯- → ζ- is unlikely, and most evidence in fact points to the contrary.[9]

It could also be of pre-Greek origin, though Beekes is not sure either way.[9] Due to his role as the west wind, his name and various derivatives of it were used to mean 'western',[9] like for example the Greek colony of Epizephyrian Locri in southern Italy, west of Greece.

Family

Parents

Zephyrus, like the rest of the wind gods, the Anemoi (Boreas, Eurus and Notus) was said to be the son of Eos, the goddess of the dawn, by her husband and first cousin Astraeus, a minor god related to the stars.[10] The poet Ovid dubs the four of them 'the Astraean brothers' in reference to their paternity.[11] He is thus also brother to the rest of Eos and Astraeus's children, namely the five star-gods (Astra Planeta) and the justice goddess Astraea. His mortal half-brothers include Memnon and Emathion, sons of his mother Eos by the Trojan prince Tithonus. The Athenian playwright Aeschylus however in his fifth-century BC play Agamemnon writes that Zephyrus is the son of the goddess Gaia (the mother earth) instead (the father, if one exists at all, is not named).[12]

Consorts and offspring

_03_ies.jpg.webp)

In Greek tradition, Zephyrus became the consort of Iris, the goddess of the rainbow and messenger of the gods. According to Nonnus, a late-antiquity poet, together they became the parents of Pothos,[13] the god of desire, and according to Alcaeus of Mytilene (a six-century BC poet from the island of Lesbos), of Eros as well, though he is more commonly a son of Ares and Aphrodite.[14] In the same passage, Zephyrus is described as having golden hair.

By the Harpy Podarge (who is Iris's sister) he became the father of Balius and Xanthus, the two fast, talking horses that were given to Achilles,[15][16] when he mated with her while she was grazing on a meadow near the banks of the Ocean, implied in the form of a mare.[17] Quintus Smyrnaeus also says that by a Harpy he had Arion, the talking horse.[18] Like with the case of Eros, Arion's more common parentage is different, in this case the Olympians Demeter and Poseidon.[19]

In some sources Zephyrus has a son named Carpus ("fruit") by a nymph Hora, who drowned in the Maeander river when the wind drove a wave right into his face, driving his lover Calamus into despair, who went on to take his life.[20][21][22] According to Pseudo-Oppian, he also became the genitor of tigers by an unnamed consort.[23]

Mythology

West Wind

Zephyrus, along with his brother Boreas, is one of the most prominent of the Anemoi; they are frequently mentioned together by poets, and along with a third brother, Notus (the south wind) they were seen as the three useful and favourable winds (the east wind, Eurus, seen as bad omen).[1] They are the three wind gods mentioned by Hesiod, as ancient Greeks avoided talking about Eurus.[2] Zephyrus and Boreas were thought to dwell together in a palace in Thrace.[15]

In the Odyssey however, they all seem to dwell on the island of Aeolia, as Zeus has tasked Aeolus with the job of the keeper of the winds.[24] Aeolus receives Odysseus and his wretched crew, and hosts them for a month gracefully.[25] As they part, Aeolus gives Odysseus a bag containing all the winds, except for Zephyrus himself, who is let free to blow Odysseus's ship gently back to Ithaca; Odysseus's crewmates however foolishly open the bag, thinking it to contain some treasure, and set free all the other winds as well, blowing the ships back to Aeolia.[24] Many years later, right after Odysseus left Calypso, the sea-god Poseidon in rage unleashed all four of them to cause a storm and raise great waves in order to drown Odysseus in the sea.[26]

In the Iliad, Zephyrus is visited by his wife Iris in his home as he dines with his wind brothers to summon him, along with Boreas, so that they blow on Patroclus's funeral pyre following his death, as Achilles prayed for their help when the pyre failed to kindle.[27][28] In the Dionysiaca, all four live together with their father Astraeus; Zephyrus plays sweet notes with an aulos for Demeter when she pays them a visit.[29]

In the myth of Eros and Psyche, Zephyrus serves Eros, the god of love, by transporting his bride-to-be, the mortal princess Psyche with his soft breeze from the cliff she had been left in on an oracle's suggestion to Eros's palace.[30] Later, he also helps rather reluctantly Psyche's two sisters transport the same way to the palace as well, when Psyche wishes to see them again.[31] After Eros abandons Psyche over her betrayal, both sisters take advantage of the situation and each independently goes to the cliff (having both been lied to by Psyche that Eros wished to maker her his new wife), calling for Eros to make them his bride, and Zephyrus to take them to the palace. But this time Zephyrus does not act when they jump, and thus they both fall to their deaths below, torn limb to limb and made food for the birds of prey and wild beasts.[32]

Zephyrus seems to have had a connection to swans; in Philostratus the Elder's works, he joins them twice in their song, once while they are carrying the Erotes and another when the young Phaethon is killed driving his father Helios's fiery chariot.[33][34] This apparently symbolizes the belief that swans took to singing when the mild west wind blew.[35]

Other myths

In his most notable myth, Zephyrus fell in love with a beautiful Spartan prince named Hyacinthus, who nevertheless rejected him[36] and became the lover of another god, Apollo.[37] One day that the prince and Apollo were playing a game of discus, Zephyrus deflected the course of Apollo's discus, redirecting it right onto Hyacinthus's head, fatally wounding him. His blood then became a new flower, the hyacinth.[lower-alpha 1] In some versions, Zephyrus is supplanted by his brother Boreas as the wind-god that bore a one-sided love for the beautiful prince.[40] Zephyrus's role in this myth reflects his connection to flowers and springtime as the gentle west wind, who, in spite of his traditional gentleness, is nonetheless a harsh lover like all winds are.[37] Not every version of this tale features Zephyrus however, as his participation is a secondary narrative; in many of them he is absent, and Hyacinthus's death is a genuine accident on Apollo's part.[17][37]

Another time, Zephyrus became lovers with another beautiful youth named Cyparissus ("cypress").[41][42] The youth, wanting to preserve his beauty, fled to Mount Cassium in Syria, where he was transformed into a cypress tree.[43][44] This myth which might be of Hellenistic origin seems to have been modeled after that of Apollo and Daphne.[44] It also, along with Zephyrus's role in Hyacinthus's story, fits the pattern–also fit by his brother Boreas–of a wind god appearing in the story of the creation of a plant.[43] In all other narratives however Zephyrus is absent, and the role of Cyparissus's divine partner is filled by Apollo; furthermore, Cyparissus is transformed into a cypress after accidentally killing his deer, which caused him much stress.[43]

Zephyrus also features in some of the dialogues by the satirical author Lucian of Samosata; in the Dialogues of the Sea Gods, he appears in two dialogues with his brother Notus, the god of the south wind. In the first, they discuss the Argive princess Io and how she was loved and got turned into a heifer by Zeus in order to hide from his jealous wife Hera,[45] while in the second, Zephyrus enthusiastically recounts the scene he has just witnessed of how Zeus transformed into a bull, tricked another princess, the Phoenician Europa, into riding him, transported her to Crete and then mated with her while Notus expresses his jealousy and complains of seeing nothing noteworthy.[46]

In ancient culture

Iconography

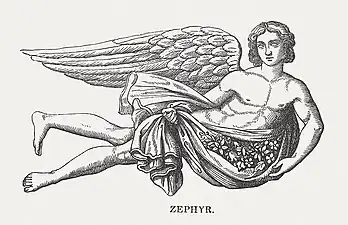

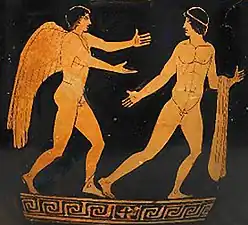

Like all the other wind gods, Zephyrus is represented in ancient Greek art with wings,[47] due to which he is sometimes hard to distinguish from Eros, another winged youthful god, though tellingly unlike Zephyrus Eros is not depicted pursuing males.[48] In ancient vases, he is most commonly pursuing the young Hyacinthus or already holding him in his arms in an erotic and sexual manner; on a red-figure vase in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Zephyrus's erect penis thrusts into the folds of the young man's clothes as they fly together,[49] while vase 95.31 from the same museum depicts intercrural sex between the two.[50] Various other vases also show scenes of Zephyrus grabbing and seizing Hyacinthus.[51][52]

On the Tower of the Winds, a clocktower/horologion in the Roman agora of Athens, the frieze depicts Zephyrus alongside seven more of the wind gods above the sundials. Zephyrus is presented as a beardless youth carrying a cloak full of flowers.[53]

On the Pergamon Altar, which depicts the battle of the gods against the Giants (known as the Gigantomachy), Zephyrus and the other three wind gods are shown in the shape of horses who pull the chariot of the goddess Hera in the eastern frieze of the monument;[54][55] the equine forms of the Anemoi are also found in Quintus Smyrnaeus's works, where the four brothers pull Zeus's chariot instead.[56]

Cult

Ancient cult of the wind gods is attested in several ancient Greek states.[57] According to the geographer Pausanias, the Winds were jointly worshipped in the town of Titane, in Sicyon, where the local priest offered sacrifice to them,[58][59] and in Coronea, a town in Boeotia.[60] It is also known that the citizens of Laciadae in Attica had erected an altar for Zephyrus.[61] According to a fragment doubtfully attributed to the fifth-century BC poet Bacchylides, a Rhodian farmer named Eudemus built a temple in honour of the west wind god, in gratitude for his help.[62]

Favonius

_-_WGA2772.jpg.webp)

Zephyrus's Roman equivalent was called Favonius (the "favouring") who held dominion over plants and flowers, however 'Zephyrus' was also commonly used by Romans. Some later authors would also describe him as having wings in his head.[63] The Roman poet Horace writes:[64]

quid fles, Asterie, quem tibi candidi |

Why do you weep, Asterie, for the man whom the bright west winds |

Unlike Greek authors, Roman writers held that Zephyrus/Favonius married not Iris but rather a local vegetation and fertility goddess named Flora (identified and linked by Ovid with a minor Greek nymph named Chloris and her legend[65]) after abducting her while she tried to run away and escape him; he gave her dominion over flowers, thus making amends for his violence and abduction of her.[1][66]

Some analysts have suggested that Carpus, the son Zephyrus had by Hora/a Hora (season goddess), is supposed to have been actually mothered by Flora/Chloris instead, although this is not confirmed in any ancient text.[67]

Genealogy

| Zephyrus's family tree[68] |

|---|

Gallery

- Zephyrus in Art

_-_Flora_And_Zephyr_(1875).jpg.webp) Flora and Zephyr by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, oil on canvas.

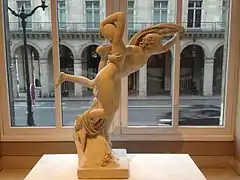

Flora and Zephyr by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, oil on canvas. Statue of Zephyrus in Hermitage Hall.

Statue of Zephyrus in Hermitage Hall..jpg.webp) Zephyrus and Boreas surround Oceanus in a mosaic from Portugal.

Zephyrus and Boreas surround Oceanus in a mosaic from Portugal. Zephyrus, Psyche and Eros, statue by John Gibson.

Zephyrus, Psyche and Eros, statue by John Gibson. Zephyrus, 1878 engraving.

Zephyrus, 1878 engraving. Statue of Zephyrus in Poland.

Statue of Zephyrus in Poland. Zephyrus, Flora and Cupid by Antonio Balestra.

Zephyrus, Flora and Cupid by Antonio Balestra. Zephyrus with Venus, Ariadne and Bacchus, eighteenth century.

Zephyrus with Venus, Ariadne and Bacchus, eighteenth century. Zephyrus and Hyacinthus red-figure, 440-420 BC.

Zephyrus and Hyacinthus red-figure, 440-420 BC. Hyacinthus and Zephyrus. Attic Red Figure Kylix. Attributed to Manner of Douris Painter, 500-450 B.C.

Hyacinthus and Zephyrus. Attic Red Figure Kylix. Attributed to Manner of Douris Painter, 500-450 B.C. Statue of Zephyrus in the gardens of Peterhof.

Statue of Zephyrus in the gardens of Peterhof._-_Sebastiano_Ricci.jpg.webp) Zéphyr et Flore by Sebastiano Ricci, oil on canvas.

Zéphyr et Flore by Sebastiano Ricci, oil on canvas. Engraving of Zephyrus.

Engraving of Zephyrus.

See also

Footnotes

- The flower that the ancient Greeks believed Hyacinthus turned into was not however what is today known as the hyacinth, as ancient description does not match.[38] The flower most likely to have been the ancient hyacinth is the larkspur, while other candidates include the iris and gladiolus italicus.[39]

References

- Rausch, Sven (2006). "Zephyrus". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill's New Pauly. Translated by Christine F. Salazar. Hamburg: Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e12216400. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- Kerenyi 1951, p. 205.

- Liddell & Scott 1940, s.v. Ζέφυρος.

- Казанскене, В. П.; Казанский, Н. Н (1986). "ze-pu₂-ro". Предметно-понятийный словарь греческого языка. Крито-микенский период (in Russian). Leningrad (Saint Petersburg), Russia: Nauka. p. 64.

- Davis & Laffineur 2020, p. 12.

- Raymoure, K. A. "a-ne-mo". Linear B Transliterations. Deaditerranean. Dead Languages of the Mediterranean. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2014-03-28."KN Fp 1 + 31"."KN 13 Fp(1) (138)".

- "DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo - Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas".

- Rix 2001, p. 309.

- Beekes 2009, p. 499.

- Hesiod, Theogony 378, Hyginus Preface; Apollodorus 1.2.3; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 6.28

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 14.545

- Aeschylus, Agamemnon 690

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 47.340

- Alcaeus of Mytilene fragment 149 [Page, p. 82.]

- Smith 1873, s.v. Zephyrus.

- Grimal 1987, s.v. Balius.

- Hard 2004, p. 58.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 4.569

- Graf, Fritz (2006). "Areion". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill's New Pauly. Translated by Christine F. Salazar. Columbus, Ohio: Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e133590. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- Servius On Eclogues 5.48; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 11.385-481

- Frey, Alexandra; Folkerts, Menso (2006). "Carpus". In Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth (eds.). Brill's New Pauly. Translated by Christine F. Salazar. Hamburg: Brill Reference Online. doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e609540. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- Forbes Irving 1990, pp. 278–2789.

- Oppian, Cynegetica 1.320, 3.350

- Myrsiades 2019, p. 104.

- Homer, Odyssey 1-45

- Hard 2004, p. 100.

- Homer, the Iliad 23.192-225

- Hard 2004, p. 48.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 6.28

- Kenney 1990, p. 49.

- Kenney 1990, p. 57.

- Kenney 1990, pp. 81-83.

- Roman & Roman 2010, p. 521.

- Ferrari 2008, p. 58.

- Poetica. Vol. 3–6. Sanseido International. 1975. p. 51.

- Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods 14: Apollo and Hermes

- Forbes Irving 1990, pp. 280–281.

- Raven, J. E. (2000), Plants and Plant Lore in Ancient Greece, Oxford: Leopard Head Press, pp. 26–27, ISBN 978-0-904920-40-6

- Dunagan, Patrick James; Lazzara, Marina; Whittington, Nicholas James (October 6, 2020). Roots and Routes: Poetics at New College of California. Delaware, United States: Vernon Press. pp. 71—76. ISBN 978-1-64889-052-9.

- Smith 1873, s.v. Hyacinthus.

- Servius, On the Aeneid 3.680

- Rosemary M. Wright. "A Dictionary of Classical Mythology: Summary of Transformations". mythandreligion.upatras.gr. University of Patras. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- Forbes Irving 1990, pp. 260–261.

- Hard 2004, p. 571.

- Lucian, Dialogues of the Sea Gods 7: South Wind and West Wind I

- Lucian, Dialogues of the Sea Gods 15: South Wind and West Wind II

- Boardman, John (1985). The Athenian Red-Figure Vases: The Archaic Period. London, UK: Thames & Hudson. p. 230. ISBN 9780500201435.

- Gantz 1996, p. 94.

- Dover 1989, p. 98.

- Beazley 1918, p. 98.

- Dover 1989, p. 75.

- Dover 1989, p. 93.

- Noble, Joseph V.; de Solla Price, Derek J. (1968). "The Water Clock in the Tower of the Winds". American Journal of Archaeology. 72 (4): 345–355. doi:10.2307/503828. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 503828. S2CID 193112893 – via JSTOR.

- LIMC 617 (Venti)

- Kunze, Max (1988). Der grosse Marmoraltar von Pergamon [The Large Marble Altar of Pergamon] (in German). Berlin: Staatliche Museem zu Berlin. pp. 23–24.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy 12.189

- Farnell 1909, p. 416.

- Farnell 1909, p. 417.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.12.1

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 9.34.3

- Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.37.2

- Silver, Isidore (1945). "Du Bellay and Hellenic Poetry". PMLA. Cambridge University Press. 60 (4): 949–50. doi:10.2307/459286. JSTOR 459286. S2CID 163633516. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- Smith 1873, s.v. Venti.

- Horace, Odes 3.7.

- Grimal 1987, s.v. Flora.

- Ovid, Fasti 5.195-212

- Guirand & Graves 1987, p. 138.

- Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- Although usually the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, as in Hesiod, Theogony 371–374, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- Astraea is not mentioned by Hesiod, instead she is given as a daughter of Eos and Astraeus in Hyginus Astronomica 2.25.1.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 507–511, Clymene, one of the Oceanids, the daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351, was the mother by Iapetus of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus, while according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus.

- According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

Bibliography

- Aeschylus, Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 2.Agamemnon. Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Beazley, John Davidson (1918). Attic red-figured vases in American museums. London: Harvard University Press.

- Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009). Lucien van Beek (ed.). Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series. Vol. 1. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill Publications. ISBN 978-90-04-17420-7.

- Davis, Brent; Laffineur, Robert, eds. (March 13, 2020). Neoteros: Studies in Bronze Age Aegean Art and Archaeology in Honor of Professor John G. Younger on the Occasion of his Retirement. ISD LLC. ISBN 978-90-429-4179-3.

- Dover, Kenneth James (1989). Greek Homosexuality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36270-5.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard (1909). The Cults of the Greek States. Vol. V. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

- Ferrari, Gloria (2008). Alcman and the Cosmos of Sparta. USA: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66867-3.

- Forbes Irving, Paul M. C. (1990). Metamorphosis in Greek Myths. Oxford, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814730-9.

- Gantz, Timothy (1996). Early Greek Myth: A guide to literary and artistic sources. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; in two volumes: (Vol. 1) ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9; (Vol. 2) ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3.

- Grimal, Pierre (1987). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Translated by A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. New York, USA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13209-0.

- Guirand, Felix; Graves, Robert (December 16, 1987). New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Translated by Richard Aldington; Delano Ames. Crescent Books. ISBN 0517004046.

- Hard, Robin (2004). The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology". Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415186360.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Kenney, Edward J. (December 8, 1990). Apuleius: Cupid and Psyche. Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26038-8.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- Kunze, Max (1994). Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC). Vol. VII.1. Zürich and Munich: Artemis Verlag. ISBN 3-7608-8751-1.

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Online version at Perseus.tufts project.

- Lucian, The Works of Lucian of Samosata, translated by H. W. Fowler and F. G. Fowler, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1905.

- Maurus Servius Honoratus, In Vergilii carmina comentarii. Servii Grammatici qui feruntur in Vergilii carmina commentarii; recensuerunt Georgius Thilo et Hermannus Hagen. Georgius Thilo. Leipzig. B. G. Teubner. 1881. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Myrsiades, Kostas (April 5, 2019). Reading Homer's Odyssey. Pennsylvania, USA: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 9781684481361.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, III Books XXXVI-XLVIII. Loeb Classical Library No. 346, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive.

- Oppian, Cynegetica in Oppian, Colluthus, Tryphiodorus. Oppian, Colluthus, and Tryphiodorus. Translated by A. W. Mair. Loeb Classical Library 219. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1928. Online version at Internet Archive.

- Ovid, Ovid's Fasti: With an English translation by Sir James George Frazer, London: W. Heinemann LTD; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1959. Internet Archive.

- Page, Denys Lionel (1968). Lyrica Graeca Selecta. Oxford Classical Texts. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814567-5.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Quintus Smyrnaeus, Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, translated by A.S. Way, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1913. Internet Archive.

- Rix, Helmut (2001). Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben [Lexicon of Indo-European Verbs] (in German) (2 ed.). Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. ISBN 3895002194.

- Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-7242-2.

- Smith, William (1873). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London, UK: John Murray, printed by Spottiswoode and Co. Online version at the Perseus.tufts library.