Amniotic fluid embolism

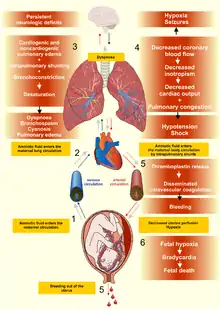

An amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) is a very uncommon childbirth (obstetric) emergency in which amniotic fluid enters the blood stream of the mother, triggering a serious reaction, which results in cardiorespiratory (heart and lung) collapse and massive bleeding (coagulopathy).[1][2][3] The rate at which it occurs is 1 instance per 20,000 births and it comprises 10% of all maternal deaths. This condition is unpredictable and no risk factors have been verified.[4]

| Amniotic fluid embolism | |

|---|---|

| |

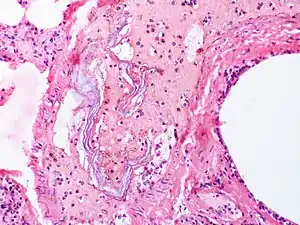

| Intravascular squames are present in this example of amniotic fluid embolism. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Risk factors | Unpredictable |

| Frequency | 1 in 20,000 births |

Signs and symptoms

Amniotic fluid embolism is suspected when a woman giving birth experiences very sudden insufficient oxygen to body tissues, low blood pressure, and profuse bleeding due to defects in blood coagulation. Though symptoms and signs can be profound, they also can be entirely absent. There is much variation in how each instance progresses.[2]

Causes

AFE is very rare and complex. The disorder occurs during the last stages of labor when amniotic fluid enters the circulatory system of the mother via tears in the placental membrane or uterine vein rupture.[5] Upon later analysis, fetal cells are found in the maternal circulation. When the fetal cells and amniotic fluid enter the bloodstream, reactions occur that cause severe changes in the mechanisms that affect blood clotting. Disseminated intravascular coagulation occurs and results in serious bleeding.[6] The condition can also develop after elective abortion, amniocentesis, cesarean delivery, or trauma. Small lacerations in the lower reproductive tract are associated with AFE.[2]

According to one study, induction of labor may double the risk of AFE. However, other studies have refuted this claim. A maternal age of 35 years or older is associated with AFE.[7]

Diagnosis

AFE is diagnosed when all other causes have been excluded. The presence of fetal squamous cells or other fetal tissues, including meconium, have been found in the maternal circulation after the event. Diagnosis is also based upon the signs and symptoms observed during the birth or procedures.[2]

Treatment

A case report on Amniotic Fluid Embolism published in the A & A Practice Journal in 2020 has revealed that when milrinone is administered as an aerosol, selective pulmonary vasodilation occurs without significant changes[8] in mean arterial pressure or systemic vascular resistance; and if used immediately after Amniotic Fluid Embolism, inhaled milrinone may mitigate the pulmonary vasoconstriction.[9][10]

However, since the circumstances that lead to this complication are difficult to influence, treatment to resolve the symptoms and deteriorating vascular conditions can improve outcomes.[2]

Epidemiology

Amniotic fluid embolism is very uncommon and the rate at which it occurs is 1 instance per 20,000 births. Though rare, it comprises 10% of all maternal deaths.[2]

History

This rare complication has been recorded seventeen times prior to 1950. The complication was originally described in 1926 by J. R. Meyer at the University of Sao Paulo.[11][12] A 1941 case study of eight autopsies of pregnant women who died suddenly during childbirth by Clarence Lushbaugh and Paul Steiner enabled widespread recognition of the diagnosis within the medical community, and was eventually republished as a landmark paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.[12][13]

References

- Stafford, Irene; Sheffield, Jeanne (2007). "Amniotic Fluid Embolism". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 34 (3): 545–553. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2007.08.002. ISSN 0889-8545. PMID 17921014.[subscription required]

- Stein, Paul (2016). Pulmonary embolism. Chichester, West Sussex, UK Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 9781119039099.

-

- Leveno, Kenneth (2016). Williams manual of pregnancy complications. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 223–224. ISBN 9780071765626.

- "Amniotic Fluid Embolism".

- Vinay Kumar; Abul K. Abbas; Nelson Fausto; Jon C. Aster (2014-08-27). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, Professional Edition E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-323-29639-7.

- "Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Kramer, M.S.; Rouleau, Jocelyn; Baskett, Thomas F; Joseph, KS (2006). "Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labour: a retrospective, population-based cohort study". The Lancet. 368 (9545): 1444–1448. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69607-4. PMID 17055946. S2CID 24883108.

- Baxter, Frederick, MD, CCFP, Whippey, Amanda, MD, FRCPC. Amniotic Fluid Embolism Treated With Inhaled Milrinone: A Case Report. A A Pract. 2020;14(13):e01342. doi:10.1213/XAA.0000000000001342.

- Gebhard CE, Rochon A, Cogan J, et al. Acute right ventricular failure in cardiac surgery during cardiopulmonary bypass separation: a retrospective case series of 12 years' experience with intratracheal milrinone administration. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019; 33:651-660

- Sablotzki A, Starzmann W, Scheubel R, Grond S, Czeslick EG. Selective pulmonary vasodilation with inhaled aerosolized milrinone in heart transplant candidates. Can J Anaesth. 2005; 52:1076-1082

- "CEArticlePrint". nursingcenter.com. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- Caeiro, Ana Filipa Cabrita; Ramilo, Irina Dulce Tapadinhas Matos; Santos, Ana Paula; Ferreira, Elizabeth; Batalha, Isabel Santos (July 2017). "Amniotic Fluid Embolism. Is a New Pregnancy Possible? Case Report". Brazilian Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 39 (7): 369–372. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1601428. PMID 28464190.

- Steiner, Paul E.; Lushbaugh, Clarence C. (October 11, 1941). "Landmark article, Oct. 1941: Maternal pulmonary embolism by amniotic fluid as a cause of obstetric shock and unexpected deaths in obstetrics". Journal of the American Medical Association. 255 (16): 2187–2303. doi:10.1001/jama.255.16.2187. PMID 3514978 – via PubMed.

External links