Antithrombin

Antithrombin (AT) is a small glycoprotein that inactivates several enzymes of the coagulation system. It is a 432-amino-acid protein produced by the liver. It contains three disulfide bonds and a total of four possible glycosylation sites. α-Antithrombin is the dominant form of antithrombin found in blood plasma and has an oligosaccharide occupying each of its four glycosylation sites. A single glycosylation site remains consistently un-occupied in the minor form of antithrombin, β-antithrombin.[5] Its activity is increased manyfold by the anticoagulant drug heparin, which enhances the binding of antithrombin to factor IIa (prothrombin) and factor Xa.[6]

| SERPINC1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | SERPINC1, AT3, AT3D, ATIII, THPH7, serpin family C member 1, ATIII-R2, ATIII-T2, ATIII-T1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 107300 MGI: 88095 HomoloGene: 20139 GeneCards: SERPINC1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nomenclature

Antithrombin is also termed antithrombin III (AT III). The designations antithrombin I through to antithrombin IV originate in early studies carried out in the 1950s by Seegers, Johnson and Fell.[7]

Antithrombin I (AT I) refers to the absorption of thrombin onto fibrin after thrombin has activated fibrinogen. Antithrombin II (AT II) refers to a cofactor in plasma, which together with heparin interferes with the interaction of thrombin and fibrinogen. Antithrombin III (AT III) refers to a substance in plasma that inactivates thrombin. Antithrombin IV (AT IV) refers to an antithrombin that becomes activated during and shortly after blood coagulation.[8] Only AT III and possibly AT I are medically significant. AT III is generally referred to solely as "antithrombin" and it is antithrombin III that is discussed in this article.

Structure

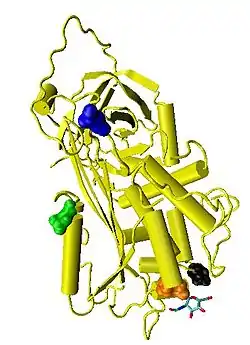

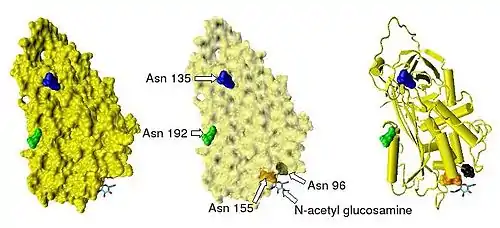

Antithrombin has a half-life in blood plasma of around 3 days.[9] The normal antithrombin concentration in human blood plasma is high at approximately 0.12 mg/ml, which is equivalent to a molar concentration of 2.3 μM.[10] Antithrombin has been isolated from the plasma of a large number of species additional to humans.[11] As deduced from protein and cDNA sequencing, cow, sheep, rabbit and mouse antithrombins are all 433 amino acids in length, which is one amino acid longer than human antithrombin. The extra amino acid is thought to occur at amino acid position 6. Cow, sheep, rabbit, mouse, and human antithrombins share between 84 and 89% amino acid sequence identity.[12] Six of the amino acids form three intramolecular disulfide bonds, Cys8-Cys128, Cys21-Cys95, and Cys248-Cys430. They all have four potential N-glycosylation sites. These occur at asparagine (Asn) amino acid numbers 96, 135, 155, and 192 in humans and at similar amino acid numbers in other species. All these sites are occupied by covalently attached oligosaccharide side-chains in the predominant form of human antithrombin, α-antithrombin, resulting in a molecular weight for this form of antithrombin of 58,200.[5] The potential glycosylation site at asparagine 135 is not occupied in a minor form (around 10%) of antithrombin, β-antithrombin (see Figure 1).[13]

Recombinant antithrombins with properties similar to those of normal human antithrombin have been produced using baculovirus-infected insect cells and mammalian cell lines grown in cell culture.[14][15][16][17] These recombinant antithrombins generally have different glycosylation patterns to normal antithrombin and are typically used in antithrombin structural studies. For this reason many of the antithrombin structures stored in the protein data bank and presented in this article show variable glycosylation patterns.

Antithrombin begins in its native state, which has a higher free energy compared to the latent state, which it decays to on average after 3 days. The latent state has the same form as the activated state - that is, when it is inhibiting thrombin. As such it is a classic example of the utility of kinetic vs thermodynamic control of protein folding.

Function

Antithrombin is a serpin (serine protease inhibitor) and is thus similar in structure to most other plasma protease inhibitors, such as alpha 1-antichymotrypsin, alpha 2-antiplasmin and Heparin cofactor II.

The physiological target proteases of antithrombin are those of the contact activation pathway (formerly known as the intrinsic pathway), namely the activated forms of Factor X (Xa), Factor IX (IXa), Factor XI (XIa), Factor XII (XIIa) and, to a greater extent, Factor II (thrombin) (IIa), and also the activated form of Factor VII (VIIa) from the tissue factor pathway (formerly known as the extrinsic pathway).[20] The inhibitor also inactivates kallikrein and plasmin , also involved in blood coagulation. However it inactivates certain other serine proteases that are not involved in coagulation such as trypsin and the C1s subunit of the enzyme C1 involved in the classical complement pathway.[12][21]

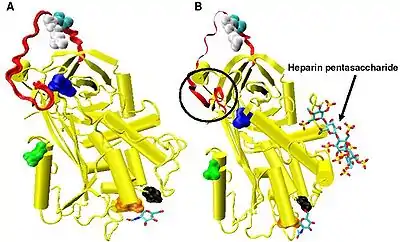

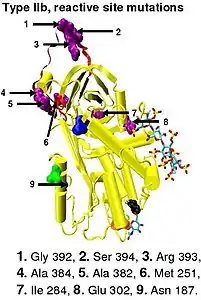

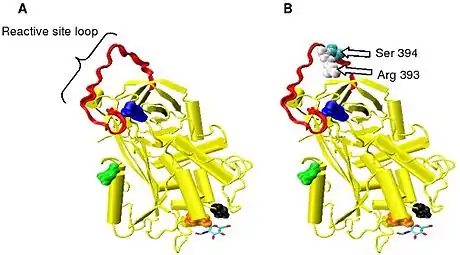

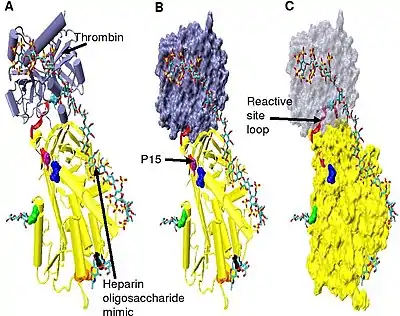

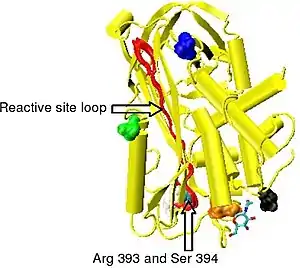

Protease inactivation results as a consequence of trapping the protease in an equimolar complex with antithrombin in which the active site of the protease enzyme is inaccessible to its usual substrate.[12] The formation of an antithrombin-protease complex involves an interaction between the protease and a specific reactive peptide bond within antithrombin. In human antithrombin this bond is between arginine (arg) 393 and serine (ser) 394 (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).[12]

It is thought that protease enzymes become trapped in inactive antithrombin-protease complexes as a consequence of their attack on the reactive bond. Although attacking a similar bond within the normal protease substrate results in rapid proteolytic cleavage of the substrate, initiating an attack on the antithrombin reactive bond causes antithrombin to become activated and trap the enzyme at an intermediate stage of the proteolytic process. Given time, thrombin is able to cleave the reactive bond within antithrombin and an inactive antithrombin-thrombin complex will dissociate, however the time it takes for this to occur may be greater than 3 days.[22] However, bonds P3-P4 and P1'-P2' can be rapidly cleaved by neutrophil elastase and the bacterial enzyme thermolysin, respectively, resulting in inactive antithrombins no longer able to inhibit thrombin activity.[23]

The rate of antithrombin's inhibition of protease activity is greatly enhanced by its additional binding to heparin, as is its inactivation by neutrophil elastase.[23]

Antithrombin and heparin

Antithrombin inactivates its physiological target enzymes, Thrombin, Factor Xa and Factor IXa with rate constants of 7–11 x 103, 2.5 x 103 M−1 s−1 and 1 x 10 M−1 s−1 respectively.[5][24] The rate of antithrombin-thrombin inactivation increases to 1.5 - 4 x 107 M−1 s−1 in the presence of heparin, i.e. the reaction is accelerated 2000-4000 fold.[25][26][27][28] Factor Xa inhibition is accelerated by only 500 to 1000 fold in the presence of heparin and the maximal rate constant is 10 fold lower than that of thrombin inhibition.[25][28] The rate enhancement of antithrombin-Factor IXa inhibition shows an approximate 1 million fold enhancement in the presence of heparin and physiological levels of calcium.[24]

AT-III binds to a specific pentasaccharide sulfation sequence contained within the heparin polymer

GlcNAc/NS(6S)-GlcA-GlcNS(3S,6S)-IdoA(2S)-GlcNS(6S)

Upon binding to this pentasaccharide sequence, inhibition of protease activity is increased by heparin as a result of two distinct mechanisms.[29] In one mechanism heparin stimulation of Factor IXa and Xa inhibition depends on a conformational change within antithrombin involving the reactive site loop and is thus allosteric.[30] In another mechanism stimulation of thrombin inhibition depends on the formation of a ternary complex between AT-III, thrombin, and heparin.[30]

Allosteric activation

Increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition requires the minimal heparin pentasaccharide sequence. The conformational changes that occur within antithrombin in response to pentasaccharide binding are well documented.[18][31][32]

In the absence of heparin, amino acids P14 and P15 (see Figure 3) from the reactive site loop are embedded within the main body of the protein (specifically the top of beta sheet A). This feature is in common with other serpins such as heparin cofactor II, alpha 1-antichymotrypsin and MENT.

The conformational change most relevant for Factor IXa and Xa inhibition involves the P14 and P15 amino acids within the N-terminal region of the reactive site loop (circled in Figure 4 model B). This region has been termed the hinge region. The conformational change within the hinge region in response to heparin binding results in the expulsion of P14 and P15 from the main body of the protein and it has been shown that by preventing this conformational change, increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition does not occur.[30] It is thought that the increased flexibility given to the reactive site loop as a result of the hinge region conformational change is a key factor in influencing increased Factor IXa and Xa inhibition. It has been calculated that in the absence of the pentasaccharide only one in every 400 antithrombin molecules (0.25%) is in an active conformation with the P14 and P15 amino acids expelled.[30]

Non-allosteric activation

Increased thrombin inhibition requires the minimal heparin pentasaccharide plus at least an additional 13 monomeric units.[33] This is thought to be due to a requirement that antithrombin and thrombin must bind to the same heparin chain adjacent to each other. This can be seen in the series of models shown in Figure 5.

In the structures shown in Figure 5 the C-terminal portion (P' side) of the reactive site loop is in an extended conformation when compared with other un-activated or heparin activated antithrombin structures.[34] The P' region of antithrombin is unusually long relative to the P' region of other serpins and in un-activated or heparin activated antithrombin structures forms a tightly hydrogen bonded β-turn. P' elongation occurs through the breaking of all hydrogen bonds involved in the β-turn.[34]

The hinge region of antithrombin in the Figure 5 complex could not be modelled due to its conformational flexibility, and amino acids P9-P14 are not seen in this structure. This conformational flexibility indicates an equilibrium may exist within the complex between a P14 P15 reactive site loop inserted antithrombin conformation and a P14 P15 reactive site loop expelled conformation. In support of this, analysis of the positioning of P15 Gly in the Figure 5 complex (labelled in model B) shows it to be inserted into beta sheet A (see model C).[34]

Effect of glycosylation on activity

α-Antithrombin and β-antithrombin differ in their affinity for heparin.[35] The difference in dissociation constant between the two is threefold for the pentasaccharide shown in Figure 3 and greater than tenfold for full length heparin, with β-antithrombin having a higher affinity.[36] The higher affinity of β-antithrombin is thought to be due to the increased rate at which subsequent conformational changes occur within the protein upon initial heparin binding. For α-antithrombin, the additional glycosylation at Asn-135 is not thought to interfere with initial heparin binding, but rather to inhibit any resulting conformational changes.[35]

Even though it is present at only 5–10% the levels of α-antithrombin, due to its increased heparin affinity, it is thought that β-antithrombin is more important than α-antithrombin in controlling thrombogenic events resulting from tissue injury. Indeed, thrombin inhibition after injury to the aorta has been attributed solely to β-antithrombin.[37]

Role in disease

Evidence for the important role antithrombin plays in regulating normal blood coagulation is demonstrated by the correlation between inherited or acquired antithrombin deficiencies and an increased risk of any affected individual developing thrombotic disease.[38] Antithrombin deficiency generally comes to light when a patient suffers recurrent venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Acquired antithrombin deficiency

Acquired antithrombin deficiency occurs as a result of three distinctly different mechanisms. The first mechanism is increased excretion which may occur with renal failure associated with proteinuria nephrotic syndrome. The second mechanism results from decreased production as seen in liver failure or cirrhosis or an immature liver secondary to premature birth. The third mechanism results from accelerated consumption which is most pronounced as consequence of severe injury trauma but also may be seen on a lesser scale as a result of interventions such as major surgery or cardiopulmonary bypass.[39]

Inherited antithrombin deficiency

The incidence of inherited antithrombin deficiency has been estimated at between 1:2000 and 1:5000 in the normal population, with the first family suffering from inherited antithrombin deficiency being described in 1965.[40][41] Subsequently, it was proposed that the classification of inherited antithrombin deficiency be designated as either type I or type II, based upon functional and immunochemical antithrombin analyses.[42] Maintenance of an adequate level of antithrombin activity, which is at least 70% that of a normal functional level, is essential to ensure effective inhibition of blood coagulation proteases.[43] Typically as a result of type I or type II antithrombin deficiency, functional antithrombin levels are reduced to below 50% of normal.[44]

Type I antithrombin deficiency

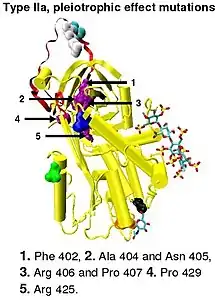

Type I antithrombin deficiency is characterized by a decrease in both antithrombin activity and antithrombin concentration in the blood of affected individuals. Type I deficiency was originally further divided into two subgroups, Ia and Ib, based upon heparin affinity. The antithrombin of subgroup Ia individuals showed a normal affinity for heparin while the antithrombin of subgroup Ib individuals showed a reduced affinity for heparin.[45] Subsequent functional analysis of a group of 1b cases found them not only to have reduced heparin affinity but multiple or 'pleiotrophic' abnormalities affecting the reactive site, the heparin binding site and antithrombin blood concentration. In a revised system of classification adopted by the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type Ib cases are now designated as type II PE, Pleiotrophic effect.[46]

Most cases of type I deficiency are due to point mutations, deletions or minor insertions within the antithrombin gene. These genetic mutations result in type I deficiency through a variety of mechanisms:

- Mutations may produce unstable antithrombins that either may be not exported into the blood correctly upon completion biosynthesis or exist in the blood for a shortened period of time, e.g., the deletion of 6 base pairs in codons 106–108.[47]

- Mutations may affect mRNA processing of the antithrombin gene.

- Minor insertions or deletions may lead to frame shift mutations and premature termination of the antithrombin gene.

- Point mutations may also result in the premature generation of a termination or stop codon e.g. the mutation of codon 129, CGA→TGA (UGA after transcription), replaces a normal codon for arginine with a termination codon.[48]

Type II antithrombin deficiency

Type II antithrombin deficiency is characterized by normal antithrombin levels but reduced antithrombin activity in the blood of affected individuals. It was originally proposed that type II deficiency be further divided into three subgroups (IIa, IIb, and IIc) depending on which antithrombin functional activity is reduced or retained.[45]

- Subgroup IIa - Decreased thrombin inactivation, decreased factor Xa inactivation and decreased heparin affinity.

- Subgroup IIb - Decreased thrombin inactivation and normal heparin affinity.

- Subgroup IIc - Normal thrombin inactivation, normal factor Xa inactivation and decreased heparin affinity.

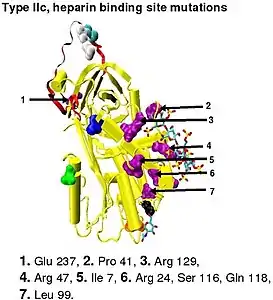

In the revised system of classification again adopted by the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type II antithrombin deficiency remains subdivided into three subgroups: the already mentioned type II PE, along with type II RS, where mutations effect the reactive site and type II HBS, where mutations effect the antithrombin heparin binding site.[46] For the purposes of an antithrombin mutational database compiled by members of the Plasma Coagulation Inhibitors Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, type IIa cases are now classified as type II PE, type IIb cases as type II RS and type IIc cases as type II HBS.[49]

Toponyms

Presently it is relatively easy to characterise a specific antithrombin genetic mutation. However prior to the use of modern characterisation techniques investigators named mutations for the town or city where the individual suffering from the deficiency resided i.e. the antithrombin mutation was designated a toponym.[50] Modern mutational characterisation has since shown that many individual antithrombin toponyms are actually the result of the same genetic mutation, for example antithrombin-Toyama, is equivalent to antithrombin-Kumamoto, -Amien, -Tours, -Paris-1, -Paris-2, -Alger, -Padua-2 and -Barcelona.[49]

Medical uses

Antithrombin is used as a protein therapeutic that can be purified from human plasma[51] or produced recombinantly (for example Atryn, which is produced in the milk of genetically modified goats[52][53]).

It is approved by the FDA as an anticoagulant for the prevention of clots before, during, or after surgery or birthing in patients with hereditary antithrombin deficiency.[51][53]

It has been studied in sepsis to reduce diffuse intravascular coagulation and other outcomes. It has not been found to confer any benefit in critically ill people with sepsis.[54]

Cleaved and latent antithrombin

Cleavage at the reactive site results in entrapment of the thrombin protease, with movement of the cleaved reactive site loop together with the bound protease, such that the loop forms an extra sixth strand in the middle of beta sheet A. This movement of the reactive site loop can also be induced without cleavage, with the resulting crystallographic structure being identical to that of the physiologically latent conformation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).[55] For this reason the conformation of antithrombin in which the reactive site loop is incorporated uncleaved into the main body of the protein is referred to as latent antithrombin. In contrast to PAI-1 the transition for antithrombin from a normal or native conformation to a latent conformation is irreversible.

Native antithrombin can be converted to latent antithrombin (L-antithrombin) by heating alone or heating in the presence of citrate.[56][57] However, without extreme heating and at 37 °C (body temperature) 10% of all antithrombin circulating in the blood is converted to the L-antithrombin over a 24-hour period.[58][59] The structure of L-antithrombin is shown in Figure 6.

The 3-dimensional structure of native antithrombin was first determined in 1994.[31][32] Unexpectedly the protein crystallized as a heterodimer composed of one molecule of native antithrombin and one molecule of latent antithrombin. Latent antithrombin on formation immediately links to a molecule of native antithrombin to form the heterodimer, and it is not until the concentration of latent antithrombin exceeds 50% of the total antithrombin that it can be detected analytically.[59] Not only is the latent form of antithrombin inactive against its target coagulation proteases, but its dimerisation with an otherwise active native antithrombin molecule also results in the native molecules inactivation. The physiological impact of the loss of antithrombin activity either through latent antithrombin formation or through subsequent dimer formation is exacerbated by the preference for dimerisation to occur between heparin activated β-antithrombin and latent antithrombin as opposed to α-antithrombin.[59]

A form of antithrombin that is an intermediate in the conversion between native and latent forms of antithrombin has also been isolated and this has been termed prelatent antithrombin.[60]

Antiangiogenic antithrombin

Angiogenesis is a physiological process involving the growth of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels. Under normal physiological conditions angiogenesis is tightly regulated and is controlled by a balance of angiogenic stimulators and angiogenic inhibitors. Tumor growth is dependent upon angiogenesis and during tumor development a sustained production of angiogenic stimulatory factors is required along with a reduction in the quantity of angiogenic inhibitory factors tumor cells produce.[61] The cleaved and latent form of antithrombin potently inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth in animal models.[62] The prelatent form of antithrombin has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in-vitro but to date has not been tested in experimental animal models.

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000117601 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026715 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Bjork, I; Olson, JE (1997). Antithrombin, A bloody important serpin (in Chemistry and Biology of Serpins). Plenum Press. pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-0-306-45698-5.

- Finley, Alan; Greenberg, Charles (2013-06-01). "Review article: heparin sensitivity and resistance: management during cardiopulmonary bypass". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 116 (6): 1210–1222. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827e4e62. ISSN 1526-7598. PMID 23408671. S2CID 22500786.

- Seegers WH, Johnson JF, Fell C (1954). "An antithrombin reaction to prothrombin activation". Am. J. Physiol. 176 (1): 97–103. doi:10.1152/ajplegacy.1953.176.1.97. PMID 13124503.

- Yin ET, Wessler S, Stoll PJ (1971). "Identity of plasma-activated factor X inhibitor with antithrombin 3 and heparin cofactor". J. Biol. Chem. 246 (11): 3712–3719. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62185-4. PMID 4102937.

- Collen D, Schetz J, de Cock F, Holmer E, Verstraete M (1977). "Metabolism of antithrombin III (heparin cofactor) in man: Effects of venous thrombosis of heparin administration". Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 7 (1): 27–35. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.1977.tb01566.x. PMID 65284. S2CID 22494710.

- Conard J, Brosstad F, Lie Larsen M, Samama M, Abildgaard U (1983). "Molar antithrombin concentration in normal human plasma". Haemostasis. 13 (6): 363–368. doi:10.1159/000214823. PMID 6667903.

- Jordan RE (1983). "Antithrombin in vertebrate species: Conservation of the heparin-dependent anticoagulant mechanism". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 227 (2): 587–595. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(83)90488-5. PMID 6607710.

- Olson ST, Björk I (1994). "Regulation of thrombin activity by antithrombin and heparin". Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 20 (4): 373–409. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1001928. PMID 7899869.

- Brennan SO, George PM, Jordan RE (1987). "Physiological variant of antithrombin-III lacks carbohydrate side-chain at Asn 135". FEBS Lett. 219 (2): 431–436. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(87)80266-1. PMID 3609301. S2CID 35438503.

- Stephens AW, Siddiqui A, Hirs CH (1987). "Expression of functionally active human antithrombin III". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (11): 3886–3890. Bibcode:1987PNAS...84.3886S. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.11.3886. PMC 304981. PMID 3473488.

- Zettlmeissl G, Conradt HS, Nimtz M, Karges HE (1989). "Characterization of recombinant human antithrombin III synthesized in Chinese hamster ovary cells". J. Biol. Chem. 264 (35): 21153–21159. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)30060-2. PMID 2592368.

- Gillespie LS, Hillesland KK, Knauer DJ (1991). "Expression of biologically active human antithrombin III by recombinant baculovirus in Spodoptera frugiperda cells". J. Biol. Chem. 266 (6): 3995–4001. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)67892-0. PMID 1995647.

- Ersdal-Badju E, Lu A, Peng X, Picard V, Zendehrouh P, Turk B, Björk I, Olson ST, Bock SC (1995). "Elimination of glycosylation heterogeneity affecting heparin affinity of recombinant human antithrombin III by expression of a beta-like variant in baculovirus-infected insect cells". Biochem. J. 310 (Pt 1): 323–330. doi:10.1042/bj3100323. PMC 1135891. PMID 7646463.

- Whisstock JC, Pike RN, et al. (2000). "Conformational changes in serpins: II. The mechanism of activation of antithrombin by heparin". J. Mol. Biol. 301 (5): 1287–1305. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3982. PMID 10966821.

- Schechter I, Berger A (1967). "On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27 (2): 157–162. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(67)80055-X. PMID 6035483.

- Persson E, Bak H, Olsen OH (2001). "Substitution of valine for leucine 305 in factor VIIa increases the intrinsic enzymatic activity". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (31): 29195–29199. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102187200. PMID 11389142.

- Ogston D, Murray J, Crawford GP (1976). "Inhibition of the activated Cls subunit of the first component of complement by antithrombin III in the presence of heparin". Thromb. Res. 9 (3): 217–222. doi:10.1016/0049-3848(76)90210-3. PMID 982345.

- Danielsson A, Björk I (1980). "Slow, spontaneous dissociation of the antithrombin-thrombin complex produces a proteolytically modified form of the inhibitor". FEBS Lett. 119 (2): 241–244. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(80)80262-6. PMID 7428936. S2CID 40067251.

- Chang WS, Wardell MR, Lomas DA, Carrell RW (1996). "Probing serpin reactive-loop conformations by proteolytic cleavage". Biochem. J. 314 (2): 647–653. doi:10.1042/bj3140647. PMC 1217096. PMID 8670081.

- Bedsted T, Swanson R, Chuang YJ, Bock PE, Björk I, Olson ST (2003). "Heparin and calcium ions dramatically enhance antithrombin reactivity with factor IXa by generating new interaction exosites". Biochemistry. 42 (27): 8143–8152. doi:10.1021/bi034363y. PMID 12846563.

- Jordan RE, Oosta GM, Gardner WT, Rosenberg RD (1980). "The kinetics of hemostatic enzyme-antithrombin interactions in the presence of low molecular weight heparin". J. Biol. Chem. 255 (21): 10081–10090. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)70431-1. PMID 6448846.

- Griffith MJ (1982). "Kinetics of the heparin-enhanced antithrombin III/thrombin reaction. Evidence for a template model for the mechanism of action of heparin". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (13): 7360–7365. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)34385-0. PMID 7085630.

- Olson ST, Björk I (1991). "Predominant contribution of surface approximation to the mechanism of heparin acceleration of the antithrombin-thrombin reaction. Elucidation from salt concentration effects". J. Biol. Chem. 266 (10): 6353–6354. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)38125-0. PMID 2007588.

- Olson ST, Björk I, Sheffer R, Craig PA, Shore JD, Choay J (1992). "Role of the antithrombin-binding pentasaccharide in heparin acceleration of antithrombin-proteinase reactions. Resolution of the antithrombin conformational change contribution to heparin rate enhancement". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (18): 12528–12538. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42309-5. PMID 1618758.

- Johnson DJ, Langdown J, Li W, Luis SA, Baglin TP, Huntington JA (2006). "Crystal structure of monomeric native antithrombin reveals a novel reactive center loop conformation". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (46): 35478–35486. doi:10.1074/jbc.M607204200. PMC 2679979. PMID 16973611.

- Langdown J, Johnson DJ, Baglin TP, Huntington JA (2004). "Allosteric activation of antithrombin critically depends upon hinge region extension". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (45): 47288–47297. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408961200. PMID 15326167.

- Schreuder HA, de Boer B, Dijkema R, Mulders J, Theunissen HJ, Grootenhuis PD, Hol WG (1994). "The intact and cleaved human antithrombin III complex as a model for serpin-proteinase interactions". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 1 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1038/nsb0194-48. PMID 7656006. S2CID 39110624.

- Carrell RW, Stein PE, Fermi G, Wardell MR (1994). "Biological implications of a 3 A structure of dimeric antithrombin". Structure. 2 (4): 257–270. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00028-9. PMID 8087553.

- Petitou M, Hérault JP, Bernat A, Driguez PA, Duchaussoy P, Lormeau JC, Herbert JM (1999). "Synthesis of Thrombin inhibiting Heparin mimetics without side effects". Nature. 398 (6726): 417–422. Bibcode:1999Natur.398..417P. doi:10.1038/18877. PMID 10201371. S2CID 4339441.

- Li W, Johnson DJ, Esmon CT, Huntington JA (2004). "Structure of the antithrombin-thrombin-heparin ternary complex reveals the antithrombotic mechanism of heparin". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 11 (9): 857–862. doi:10.1038/nsmb811. PMID 15311269. S2CID 28790576.

- McCoy AJ, Pei XY, Skinner R, Abrahams JP, Carrell RW (2003). "Structure of beta-antithrombin and the effect of glycosylation on antithrombin's heparin affinity and activity". J. Mol. Biol. 326 (3): 823–833. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01382-7. PMID 12581643.

- Turk B, Brieditis I, Bock SC, Olson ST, Björk I (1997). "The oligosaccharide side chain on Asn-135 of alpha-antithrombin, absent in beta-antithrombin, decreases the heparin affinity of the inhibitor by affecting the heparin-induced conformational change". Biochemistry. 36 (22): 6682–6691. doi:10.1021/bi9702492. PMID 9184148.

- Frebelius S, Isaksson S, Swedenborg J (1996). "Thrombin inhibition by antithrombin III on the subendothelium is explained by the isoform AT beta". Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 16 (10): 1292–1297. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.16.10.1292. PMID 8857927.

- van Boven HH, Lane DA (1997). "Antithrombin and its inherited deficiency states". Semin. Hematol. 34 (3): 188–204. PMID 9241705.

- Maclean PS, Tait RC (2007). "Hereditary and acquired antithrombin deficiency: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment options". Drugs. 67 (10): 1429–1440. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767100-00005. PMID 17600391. S2CID 46971091.

- Lane DA, Kunz G, Olds RJ, Thein SL (1996). "Molecular genetics of antithrombin deficiency". Blood Rev. 10 (2): 59–74. doi:10.1016/S0268-960X(96)90034-X. PMID 8813337.

- Egeberg O (1965). "Inherited antithrombin deficiency causing thrombophilia". Thromb. Diath. Haemorrh. 13 (2): 516–530. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1656297. PMID 14347873.

- Sas G, Petö I, Bánhegyi D, Blaskó G, Domján G (1980). "Heterogeneity of the "classical" antithrombin III deficiency". Thromb. Haemost. 43 (2): 133–136. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1650034. PMID 7455972.

- Lane DA, Olds RJ, Conard J, Boisclair M, Bock SC, Hultin M, Abildgaard U, Ireland H, Thompson E, Sas G (1992). "Pleiotropic effects of antithrombin strand 1C substitution mutations". J. Clin. Invest. 90 (6): 2422–2433. doi:10.1172/JCI116133. PMC 443398. PMID 1469094.

- Lane DA, Olds RJ, Thein SL (1994). "Antithrombin III: summary of first database update". Nucleic Acids Res. 22 (17): 3556–3559. PMC 308318. PMID 7937056.

- Sas G (1984). "Hereditary antithrombin III deficiency: biochemical aspects". Haematologica. 17 (1): 81–86. PMID 6724355.

- Lane DA, Olds RJ, Boisclair M, Chowdhury V, Thein SL, Cooper DN, Blajchman M, Perry D, Emmerich J, Aiach M (1993). "Antithrombin III mutation database: first update. For the Thrombin and its Inhibitors Subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis". Thromb. Haemost. 70 (2): 361–369. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1649581. PMID 8236149.

- Olds RJ, Lane DA, Beresford CH, Abildgaard U, Hughes PM, Thein SL (1993). "A recurrent deletion in the antithrombin gene, AT106-108(-6 bp), identified by DNA heteroduplex detection". Genomics. 16 (1): 298–299. doi:10.1006/geno.1993.1184. PMID 8486379.

- Olds RJ, Lane DA, Ireland H, Finazzi G, Barbui T, Abildgaard U, Girolami A, Thein SL (1991). "A common point mutation producing type 1A antithrombin III deficiency: AT129 CGA to TGA (Arg to Stop)". Thromb. Res. 64 (5): 621–625. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(05)80011-8. PMID 1808766.

- Imperial College London, Faculty of Medicine, Antithrombin Mutation Database. Retrieved on 2008-08-16.

- Blajchman MA, Austin RC, Fernandez-Rachubinski F, Sheffield WP (1992). "Molecular basis of inherited human antithrombin deficiency". Blood. 80 (9): 2159–2171. doi:10.1182/blood.V80.9.2159.2159. PMID 1421387.

- "Thrombate III label" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-15. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- FDA website for ATryn (BL 125284)

- Antithrombin (Recombinant) US Package Insert ATryn for Injection February 3, 2009

- Allingstrup, Mikkel; Wetterslev, Jørn; Ravn, Frederikke B.; Møller, Ann Merete; Afshari, Arash (9 February 2016). "Antithrombin III for critically ill patients: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (4): 505–520. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4225-7. PMC 2137061. PMID 26862016.

- Mottonen J, Strand A, Symersky J, Sweet RM, Danley DE, Geoghegan KF, Gerard RD, Goldsmith EJ (1992). "Structural basis of latency in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1". Nature. 355 (6357): 270–273. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..270M. doi:10.1038/355270a0. PMID 1731226. S2CID 4365370.

- Chang WS, Harper PL (1997). "Commercial antithrombin concentrate contains inactive L-forms of antithrombin". Thromb. Haemost. 77 (2): 323–328. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1655962. PMID 9157590.

- Wardell MR, Chang WS, Bruce D, Skinner R, Lesk AM, Carrell RW (1997). "Preparative induction and characterization of L-antithrombin: a structural homologue of latent plasminogen activator inhibitor-1". Biochemistry. 36 (42): 13133–13142. doi:10.1021/bi970664u. PMID 9335576.

- Carrell RW, Huntington JA, Mushunje A, Zhou A (2001). "The conformational basis of thrombosis". Thromb. Haemost. 86 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1616196. PMID 11487000.

- Zhou A, Huntington JA, Carrell RW (1999). "Formation of the antithrombin heterodimer in vivo and the onset of thrombosis". Blood. 94 (10): 3388–3396. doi:10.1182/blood.V94.10.3388.422k20_3388_3396. PMID 10552948.

- Larsson H, Akerud P, Nordling K, Raub-Segall E, Claesson-Welsh L, Björk I (2001). "A novel anti-angiogenic form of antithrombin with retained proteinase binding ability and heparin affinity". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (15): 11996–12002. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010170200. PMID 11278631.

- O'Reilly MS (2007). "Antiangiogenic antithrombin". Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 33 (7): 660–666. doi:10.1055/s-2007-991533. PMID 18000792.

- O'Reilly MS, Pirie-Shepherd S, Lane WS, Folkman J (1999). "Antiangiogenic activity of the cleaved conformation of the serpin antithrombin". Science. 285 (5435): 1926–1928. doi:10.1126/science.285.5435.1926. PMID 10489375.

Further reading

- Panzer-Heinig, Sabine (2009). Antithrombin (III) - Establishing Pediatric Reference Values, Relevance for DIC 1992 versus 2007 (Thesis). Medizinische Fakultät Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

External links

- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: I04.018

- Antithrombin+III at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human SERPINC1 genome location and SERPINC1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.