Bioinformatics

Bioinformatics (/ˌbaɪ.oʊˌɪnfərˈmætɪks/ (![]() listen)) is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, information engineering, mathematics and statistics to analyze and interpret the biological data. Bioinformatics has been used for in silico analyses of biological queries using computational and statistical techniques.

listen)) is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biological data, in particular when the data sets are large and complex. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, information engineering, mathematics and statistics to analyze and interpret the biological data. Bioinformatics has been used for in silico analyses of biological queries using computational and statistical techniques.

Bioinformatics includes biological studies that use computer programming as part of their methodology, as well as specific analysis "pipelines" that are repeatedly used, particularly in the field of genomics. Common uses of bioinformatics include the identification of candidates genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Often, such identification is made with the aim to better understand the genetic basis of disease, unique adaptations, desirable properties (esp. in agricultural species), or differences between populations. In a less formal way, bioinformatics also tries to understand the organizational principles within nucleic acid and protein sequences, called proteomics.[1]

Image and signal processing allow extraction of useful results from large amounts of raw data. In the field of genetics, it aids in sequencing and annotating genomes and their observed mutations. It plays a role in the text mining of biological literature and the development of biological and gene ontologies to organize and query biological data. It also plays a role in the analysis of gene and protein expression and regulation. Bioinformatics tools aid in comparing, analyzing and interpreting genetic and genomic data and more generally in the understanding of evolutionary aspects of molecular biology. At a more integrative level, it helps analyze and catalogue the biological pathways and networks that are an important part of systems biology. In structural biology, it aids in the simulation and modeling of DNA,[2] RNA,[2][3] proteins[4] as well as biomolecular interactions.[5][6][7][8]

History

Historically, the term bioinformatics did not mean what it means today. Paulien Hogeweg and Ben Hesper coined it in 1970 to refer to the study of information processes in biotic systems.[9][10][11][12][13] This definition placed bioinformatics as a field parallel to biochemistry (the study of chemical processes in biological systems).[10]

Sequences

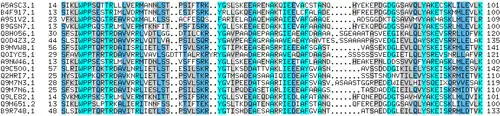

There has been a tremendous advance in speed and cost reduction since the completion of the Human Genome Project, with some labs able to sequence over 100,000 billion bases each year, and a full genome can be sequenced for a thousand dollars or less.[14] Computers became essential in molecular biology when protein sequences became available after Frederick Sanger determined the sequence of insulin in the early 1950s. Comparing multiple sequences manually turned out to be impractical. A pioneer in the field was Margaret Oakley Dayhoff.[15] She compiled one of the first protein sequence databases, initially published as books[16] and pioneered methods of sequence alignment and molecular evolution.[17] Another early contributor to bioinformatics was Elvin A. Kabat, who pioneered biological sequence analysis in 1970 with his comprehensive volumes of antibody sequences released with Tai Te Wu between 1980 and 1991.[18] In the 1970s, new techniques for sequencing DNA were applied to bacteriophage MS2 and øX174, and the extended nucleotide sequences were then parsed with informational and statistical algorithms. These studies illustrated that well known features, such as the coding segments and the triplet code, are revealed in straightforward statistical analyses and were thus proof of the concept that bioinformatics would be insightful.[19][20]

Goals

To study how normal cellular activities are altered in different disease states, the biological data must be combined to form a comprehensive picture of these activities. Therefore, the field of bioinformatics has evolved such that the most pressing task now involves the analysis and interpretation of various types of data. This also includes nucleotide and amino acid sequences, protein domains, and protein structures.[21] The actual process of analyzing and interpreting data is referred to as computational biology. Important sub-disciplines within bioinformatics and computational biology include:

- Development and implementation of computer programs that enable efficient access to, management, and use of, various types of information.

- Development of new algorithms (mathematical formulas) and statistical measures that assess relationships among members of large data sets. For example, there are methods to locate a gene within a sequence, to predict protein structure and/or function, and to cluster protein sequences into families of related sequences.

The primary goal of bioinformatics is to increase the understanding of biological processes. What sets it apart from other approaches, however, is its focus on developing and applying computationally intensive techniques to achieve this goal. Examples include: pattern recognition, data mining, machine learning algorithms, and visualization. Major research efforts in the field include sequence alignment, gene finding, genome assembly, drug design, drug discovery, protein structure alignment, protein structure prediction, prediction of gene expression and protein–protein interactions, genome-wide association studies, the modeling of evolution and cell division/mitosis.

Bioinformatics now entails the creation and advancement of databases, algorithms, computational and statistical techniques, and theory to solve formal and practical problems arising from the management and analysis of biological data.

Over the past few decades, rapid developments in genomic and other molecular research technologies and developments in information technologies have combined to produce a tremendous amount of information related to molecular biology. Bioinformatics is the name given to these mathematical and computing approaches used to glean understanding of biological processes.

Common activities in bioinformatics include mapping and analyzing DNA and protein sequences, aligning DNA and protein sequences to compare them, and creating and viewing 3-D models of protein structures.

Relation to other fields

Bioinformatics is a science field that is similar to but distinct from biological computation, while it is often considered synonymous to computational biology. Biological computation uses bioengineering and biology to build biological computers, whereas bioinformatics uses computation to better understand biology. Bioinformatics and computational biology involve the analysis of biological data, particularly DNA, RNA, and protein sequences. The field of bioinformatics experienced explosive growth starting in the mid-1990s, driven largely by the Human Genome Project and by rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology.

Analyzing biological data to produce meaningful information involves writing and running software programs that use algorithms from graph theory, artificial intelligence, soft computing, data mining, image processing, and computer simulation. The algorithms in turn depend on theoretical foundations such as discrete mathematics, control theory, system theory, information theory, and statistics.

Sequence analysis

Since the Phage Φ-X174 was sequenced in 1977,[22] the DNA sequences of thousands of organisms have been decoded and stored in databases. This sequence information is analyzed to determine genes that encode proteins, RNA genes, regulatory sequences, structural motifs, and repetitive sequences. A comparison of genes within a species or between different species can show similarities between protein functions, or relations between species (the use of molecular systematics to construct phylogenetic trees). With the growing amount of data, it long ago became impractical to analyze DNA sequences manually. Computer programs such as BLAST are used routinely to search sequences—as of 2008, from more than 260,000 organisms, containing over 190 billion nucleotides.[23]

DNA sequencing

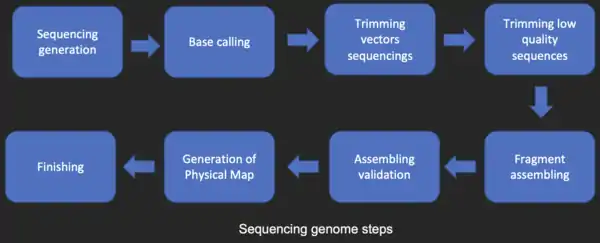

Before sequences can be analyzed they have to be obtained from the data storage bank example Genbank. DNA sequencing is still a non-trivial problem as the raw data may be noisy or affected by weak signals. Algorithms have been developed for base calling for the various experimental approaches to DNA sequencing.

Sequence assembly

Most DNA sequencing techniques produce short fragments of sequence that need to be assembled to obtain complete gene or genome sequences. The so-called shotgun sequencing technique (which was used, for example, by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) to sequence the first bacterial genome, Haemophilus influenzae)[24] generates the sequences of many thousands of small DNA fragments (ranging from 35 to 900 nucleotides long, depending on the sequencing technology). The ends of these fragments overlap and, when aligned properly by a genome assembly program, can be used to reconstruct the complete genome. Shotgun sequencing yields sequence data quickly, but the task of assembling the fragments can be quite complicated for larger genomes. For a genome as large as the human genome, it may take many days of CPU time on large-memory, multiprocessor computers to assemble the fragments, and the resulting assembly usually contains numerous gaps that must be filled in later. Shotgun sequencing is the method of choice for virtually all genomes sequenced today, and genome assembly algorithms are a critical area of bioinformatics research.

Genome annotation

In the context of genomics, annotation is the process of marking the genes and other biological features in a DNA sequence. This process needs to be automated because most genomes are too large to annotate by hand, not to mention the desire to annotate as many genomes as possible, as the rate of sequencing has ceased to pose a bottleneck. Annotation is made possible by the fact that genes have recognisable start and stop regions, although the exact sequence found in these regions can vary between genes.

Genome annotation can be classified into three levels: the nucleotide, protein, and process levels.

Gene finding is a chief aspect of nucleotide-level annotation. For complex genomes, the most successful methods use a combination of ab initio gene prediction and sequence comparison with expressed sequence databases and other organisms. Nucleotide-level annotation also allows the integration of genome sequence with other genetic and physical maps of the genome.

The principal aim of protein-level annotation is to assign function to the products of the genome. Databases of protein sequences and functional domains and motifs are powerful resources for this type of annotation. Nevertheless, half of the predicted proteins in a new genome sequence tend to have no obvious function.

Understanding the function of genes and their products in the context of cellular and organismal physiology is the goal of process-level annotation. One of the obstacles to this level of annotation has been the inconsistency of terms used by different model systems. The Gene Ontology Consortium is helping to solve this problem.[25]

The first description of a comprehensive genome annotation system was published in 1995[24] by the team at The Institute for Genomic Research that performed the first complete sequencing and analysis of the genome of a free-living organism, the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae.[24] Owen White designed and built a software system to identify the genes encoding all proteins, transfer RNAs, ribosomal RNAs (and other sites) and to make initial functional assignments. Most current genome annotation systems work similarly, but the programs available for analysis of genomic DNA, such as the GeneMark program trained and used to find protein-coding genes in Haemophilus influenzae, are constantly changing and improving.

Following the goals that the Human Genome Project left to achieve after its closure in 2003, a new project developed by the National Human Genome Research Institute in the U.S appeared. The so-called ENCODE project is a collaborative data collection of the functional elements of the human genome that uses next-generation DNA-sequencing technologies and genomic tiling arrays, technologies able to automatically generate large amounts of data at a dramatically reduced per-base cost but with the same accuracy (base call error) and fidelity (assembly error).

Gene function prediction

While genome annotation is primarily based on sequence similarity (and thus homology), other properties of sequences can be used to predict the function of genes. In fact, most gene function prediction methods focus on protein sequences as they are more informative and more feature-rich. For instance, the distribution of hydrophobic amino acids predicts transmembrane segments in proteins. However, protein function prediction can also use external information such as gene (or protein) expression data, protein structure, or protein-protein interactions.[26]

Computational evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the study of the origin and descent of species, as well as their change over time. Informatics has assisted evolutionary biologists by enabling researchers to:

- trace the evolution of a large number of organisms by measuring changes in their DNA, rather than through physical taxonomy or physiological observations alone,

- compare entire genomes, which permits the study of more complex evolutionary events, such as gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and the prediction of factors important in bacterial speciation,

- build complex computational population genetics models to predict the outcome of the system over time[27]

- track and share information on an increasingly large number of species and organisms

Future work endeavours to reconstruct the now more complex tree of life.

The area of research within computer science that uses genetic algorithms is sometimes confused with computational evolutionary biology, but the two areas are not necessarily related.

Comparative genomics

The core of comparative genome analysis is the establishment of the correspondence between genes (orthology analysis) or other genomic features in different organisms. It is these intergenomic maps that make it possible to trace the evolutionary processes responsible for the divergence of two genomes. A multitude of evolutionary events acting at various organizational levels shape genome evolution. At the lowest level, point mutations affect individual nucleotides. At a higher level, large chromosomal segments undergo duplication, lateral transfer, inversion, transposition, deletion and insertion.[28] Ultimately, whole genomes are involved in processes of hybridization, polyploidization and endosymbiosis, often leading to rapid speciation. The complexity of genome evolution poses many exciting challenges to developers of mathematical models and algorithms, who have recourse to a spectrum of algorithmic, statistical and mathematical techniques, ranging from exact, heuristics, fixed parameter and approximation algorithms for problems based on parsimony models to Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms for Bayesian analysis of problems based on probabilistic models.

Many of these studies are based on the detection of sequence homology to assign sequences to protein families.[29]

Pan genomics

Pan genomics is a concept introduced in 2005 by Tettelin and Medini which eventually took root in bioinformatics. Pan genome is the complete gene repertoire of a particular taxonomic group: although initially applied to closely related strains of a species, it can be applied to a larger context like genus, phylum, etc. It is divided in two parts- The Core genome: Set of genes common to all the genomes under study (These are often housekeeping genes vital for survival) and The Dispensable/Flexible Genome: Set of genes not present in all but one or some genomes under study. A bioinformatics tool BPGA can be used to characterize the Pan Genome of bacterial species.[30]

Genetics of disease

With the advent of next-generation sequencing we are obtaining enough sequence data to map the genes of complex diseases including infertility,[31] breast cancer[32] or Alzheimer's disease.[33] Genome-wide association studies are a useful approach to pinpoint the mutations responsible for such complex diseases.[34] Through these studies, thousands of DNA variants have been identified that are associated with similar diseases and traits.[35] Furthermore, the possibility for genes to be used at prognosis, diagnosis or treatment is one of the most essential applications. Many studies are discussing both the promising ways to choose the genes to be used and the problems and pitfalls of using genes to predict disease presence or prognosis.[36]

Analysis of mutations in cancer

In cancer, the genomes of affected cells are rearranged in complex or even unpredictable ways. Massive sequencing efforts are used to identify previously unknown point mutations in a variety of genes in cancer. Bioinformaticians continue to produce specialized automated systems to manage the sheer volume of sequence data produced, and they create new algorithms and software to compare the sequencing results to the growing collection of human genome sequences and germline polymorphisms. New physical detection technologies are employed, such as oligonucleotide microarrays to identify chromosomal gains and losses (called comparative genomic hybridization), and single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays to detect known point mutations. These detection methods simultaneously measure several hundred thousand sites throughout the genome, and when used in high-throughput to measure thousands of samples, generate terabytes of data per experiment. Again the massive amounts and new types of data generate new opportunities for bioinformaticians. The data is often found to contain considerable variability, or noise, and thus Hidden Markov model and change-point analysis methods are being developed to infer real copy number changes.

Two important principles can be used in the analysis of cancer genomes bioinformatically pertaining to the identification of mutations in the exome. First, cancer is a disease of accumulated somatic mutations in genes. Second cancer contains driver mutations which need to be distinguished from passengers.[37]

With the breakthroughs that this next-generation sequencing technology is providing to the field of Bioinformatics, cancer genomics could drastically change. These new methods and software allow bioinformaticians to sequence many cancer genomes quickly and affordably. This could create a more flexible process for classifying types of cancer by analysis of cancer driven mutations in the genome. Furthermore, tracking of patients while the disease progresses may be possible in the future with the sequence of cancer samples.[38]

Another type of data that requires novel informatics development is the analysis of lesions found to be recurrent among many tumors.

Gene and protein expression

Analysis of gene expression

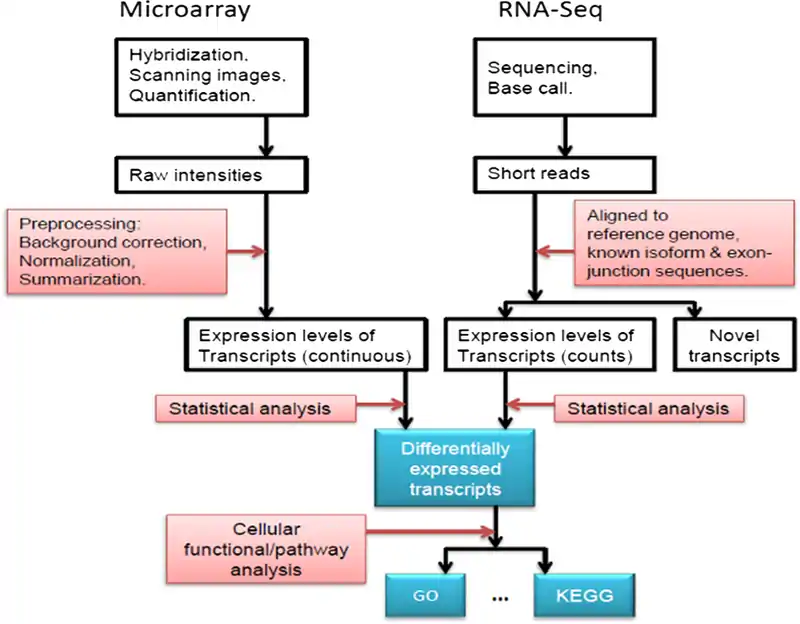

The expression of many genes can be determined by measuring mRNA levels with multiple techniques including microarrays, expressed cDNA sequence tag (EST) sequencing, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) tag sequencing, massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS), RNA-Seq, also known as "Whole Transcriptome Shotgun Sequencing" (WTSS), or various applications of multiplexed in-situ hybridization. All of these techniques are extremely noise-prone and/or subject to bias in the biological measurement, and a major research area in computational biology involves developing statistical tools to separate signal from noise in high-throughput gene expression studies.[39] Such studies are often used to determine the genes implicated in a disorder: one might compare microarray data from cancerous epithelial cells to data from non-cancerous cells to determine the transcripts that are up-regulated and down-regulated in a particular population of cancer cells.

Analysis of protein expression

Protein microarrays and high throughput (HT) mass spectrometry (MS) can provide a snapshot of the proteins present in a biological sample. Bioinformatics is very much involved in making sense of protein microarray and HT MS data; the former approach faces similar problems as with microarrays targeted at mRNA, the latter involves the problem of matching large amounts of mass data against predicted masses from protein sequence databases, and the complicated statistical analysis of samples where multiple, but incomplete peptides from each protein are detected. Cellular protein localization in a tissue context can be achieved through affinity proteomics displayed as spatial data based on immunohistochemistry and tissue microarrays.[40]

Analysis of regulation

Gene regulation is the complex orchestration of events by which a signal, potentially an extracellular signal such as a hormone, eventually leads to an increase or decrease in the activity of one or more proteins. Bioinformatics techniques have been applied to explore various steps in this process.

For example, gene expression can be regulated by nearby elements in the genome. Promoter analysis involves the identification and study of sequence motifs in the DNA surrounding the coding region of a gene. These motifs influence the extent to which that region is transcribed into mRNA. Enhancer elements far away from the promoter can also regulate gene expression, through three-dimensional looping interactions. These interactions can be determined by bioinformatic analysis of chromosome conformation capture experiments.

Expression data can be used to infer gene regulation: one might compare microarray data from a wide variety of states of an organism to form hypotheses about the genes involved in each state. In a single-cell organism, one might compare stages of the cell cycle, along with various stress conditions (heat shock, starvation, etc.). One can then apply clustering algorithms to that expression data to determine which genes are co-expressed. For example, the upstream regions (promoters) of co-expressed genes can be searched for over-represented regulatory elements. Examples of clustering algorithms applied in gene clustering are k-means clustering, self-organizing maps (SOMs), hierarchical clustering, and consensus clustering methods.

Analysis of cellular organization

Several approaches have been developed to analyze the location of organelles, genes, proteins, and other components within cells. This is relevant as the location of these components affects the events within a cell and thus helps us to predict the behavior of biological systems. A gene ontology category, cellular component, has been devised to capture subcellular localization in many biological databases.

Microscopy and image analysis

Microscopic pictures allow us to locate both organelles as well as molecules. It may also help us to distinguish between normal and abnormal cells, e.g. in cancer.

Protein localization

The localization of proteins helps us to evaluate the role of a protein. For instance, if a protein is found in the nucleus it may be involved in gene regulation or splicing. By contrast, if a protein is found in mitochondria, it may be involved in respiration or other metabolic processes. Protein localization is thus an important component of protein function prediction. There are well developed protein subcellular localization prediction resources available, including protein subcellular location databases, and prediction tools.[41][42]

Nuclear organization of chromatin

Data from high-throughput chromosome conformation capture experiments, such as Hi-C (experiment) and ChIA-PET, can provide information on the spatial proximity of DNA loci. Analysis of these experiments can determine the three-dimensional structure and nuclear organization of chromatin. Bioinformatic challenges in this field include partitioning the genome into domains, such as Topologically Associating Domains (TADs), that are organised together in three-dimensional space.[43]

Structural bioinformatics

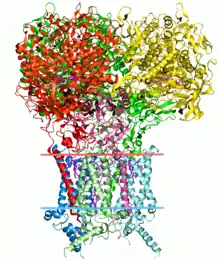

Protein structure prediction is another important application of bioinformatics. The amino acid sequence of a protein, the so-called primary structure, can be easily determined from the sequence on the gene that codes for it. In the vast majority of cases, this primary structure uniquely determines a structure in its native environment. (Of course, there are exceptions, such as the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) prion.) Knowledge of this structure is vital in understanding the function of the protein. Structural information is usually classified as one of secondary, tertiary and quaternary structure. A viable general solution to such predictions remains an open problem. Most efforts have so far been directed towards heuristics that work most of the time.

One of the key ideas in bioinformatics is the notion of homology. In the genomic branch of bioinformatics, homology is used to predict the function of a gene: if the sequence of gene A, whose function is known, is homologous to the sequence of gene B, whose function is unknown, one could infer that B may share A's function. In the structural branch of bioinformatics, homology is used to determine which parts of a protein are important in structure formation and interaction with other proteins. In a technique called homology modeling, this information is used to predict the structure of a protein once the structure of a homologous protein is known. Until recently, this remained the only way to predict protein structures reliably. However, a game-changing breakthrough occurred with the release of new deep-learning algorithms-based software called AlphaFold, developed by a bioinformatics team within Google's A.I. research department DeepMind.[44] AlphaFold, during the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) computational protein structure prediction software competition, became the first contender ever to deliver prediction submissions with accuracy competitive with experimental structures in a majority of cases and greatly outperforming all other prediction software methods up to that point.[45] AlphaFold has since released the predicted structures for hundreds of millions of proteins.[46]

One example of this is hemoglobin in humans and the hemoglobin in legumes (leghemoglobin), which are distant relatives from the same protein superfamily. Both serve the same purpose of transporting oxygen in the organism. Although both of these proteins have completely different amino acid sequences, their protein structures are virtually identical, which reflects their near identical purposes and shared ancestor.[47]

Other techniques for predicting protein structure include protein threading and de novo (from scratch) physics-based modeling.

Another aspect of structural bioinformatics include the use of protein structures for Virtual Screening models such as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship models and proteochemometric models (PCM). Furthermore, a protein's crystal structure can be used in simulation of for example ligand-binding studies and in silico mutagenesis studies.

Network and systems biology

Network analysis seeks to understand the relationships within biological networks such as metabolic or protein–protein interaction networks. Although biological networks can be constructed from a single type of molecule or entity (such as genes), network biology often attempts to integrate many different data types, such as proteins, small molecules, gene expression data, and others, which are all connected physically, functionally, or both.

Systems biology involves the use of computer simulations of cellular subsystems (such as the networks of metabolites and enzymes that comprise metabolism, signal transduction pathways and gene regulatory networks) to both analyze and visualize the complex connections of these cellular processes. Artificial life or virtual evolution attempts to understand evolutionary processes via the computer simulation of simple (artificial) life forms.

Molecular interaction networks

Tens of thousands of three-dimensional protein structures have been determined by X-ray crystallography and protein nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (protein NMR) and a central question in structural bioinformatics is whether it is practical to predict possible protein–protein interactions only based on these 3D shapes, without performing protein–protein interaction experiments. A variety of methods have been developed to tackle the protein–protein docking problem, though it seems that there is still much work to be done in this field.

Other interactions encountered in the field include Protein–ligand (including drug) and protein–peptide. Molecular dynamic simulation of movement of atoms about rotatable bonds is the fundamental principle behind computational algorithms, termed docking algorithms, for studying molecular interactions.

Others

Literature analysis

The growth in the number of published literature makes it virtually impossible to read every paper, resulting in disjointed sub-fields of research. Literature analysis aims to employ computational and statistical linguistics to mine this growing library of text resources. For example:

- Abbreviation recognition – identify the long-form and abbreviation of biological terms

- Named-entity recognition – recognizing biological terms such as gene names

- Protein–protein interaction – identify which proteins interact with which proteins from text

The area of research draws from statistics and computational linguistics.

High-throughput image analysis

Computational technologies are used to accelerate or fully automate the processing, quantification and analysis of large amounts of high-information-content biomedical imagery. Modern image analysis systems augment an observer's ability to make measurements from a large or complex set of images, by improving accuracy, objectivity, or speed. A fully developed analysis system may completely replace the observer. Although these systems are not unique to biomedical imagery, biomedical imaging is becoming more important for both diagnostics and research. Some examples are:

- high-throughput and high-fidelity quantification and sub-cellular localization (high-content screening, cytohistopathology, Bioimage informatics)

- morphometrics

- clinical image analysis and visualization

- determining the real-time air-flow patterns in breathing lungs of living animals

- quantifying occlusion size in real-time imagery from the development of and recovery during arterial injury

- making behavioral observations from extended video recordings of laboratory animals

- infrared measurements for metabolic activity determination

- inferring clone overlaps in DNA mapping, e.g. the Sulston score

High-throughput single cell data analysis

Computational techniques are used to analyse high-throughput, low-measurement single cell data, such as that obtained from flow cytometry. These methods typically involve finding populations of cells that are relevant to a particular disease state or experimental condition.

Biodiversity informatics

Biodiversity informatics deals with the collection and analysis of biodiversity data, such as taxonomic databases, or microbiome data. Examples of such analyses include phylogenetics, niche modelling, species richness mapping, DNA barcoding, or species identification tools.

Ontologies and data integration

Biological ontologies are directed acyclic graphs of controlled vocabularies. They are designed to capture biological concepts and descriptions in a way that can be easily categorised and analysed with computers. When categorised in this way, it is possible to gain added value from holistic and integrated analysis.

The OBO Foundry was an effort to standardise certain ontologies. One of the most widespread is the Gene ontology which describes gene function. There are also ontologies which describe phenotypes.

Databases

Databases are essential for bioinformatics research and applications. Many databases exist, covering various information types: for example, DNA and protein sequences, molecular structures, phenotypes and biodiversity. Databases may contain empirical data (obtained directly from experiments), predicted data (obtained from analysis), or, most commonly, both. They may be specific to a particular organism, pathway or molecule of interest. Alternatively, they can incorporate data compiled from multiple other databases. These databases vary in their format, access mechanism, and whether they are public or not.

Some of the most commonly used databases are listed below. For a more comprehensive list, please check the link at the beginning of the subsection.

- Used in biological sequence analysis: Genbank, UniProt

- Used in structure analysis: Protein Data Bank (PDB)

- Used in finding Protein Families and Motif Finding: InterPro, Pfam

- Used for Next Generation Sequencing: Sequence Read Archive

- Used in Network Analysis: Metabolic Pathway Databases (KEGG, BioCyc), Interaction Analysis Databases, Functional Networks

- Used in design of synthetic genetic circuits: GenoCAD

Software and tools

Software tools for bioinformatics range from simple command-line tools, to more complex graphical programs and standalone web-services available from various bioinformatics companies or public institutions.

Open-source bioinformatics software

Many free and open-source software tools have existed and continued to grow since the 1980s.[49] The combination of a continued need for new algorithms for the analysis of emerging types of biological readouts, the potential for innovative in silico experiments, and freely available open code bases have helped to create opportunities for all research groups to contribute to both bioinformatics and the range of open-source software available, regardless of their funding arrangements. The open source tools often act as incubators of ideas, or community-supported plug-ins in commercial applications. They may also provide de facto standards and shared object models for assisting with the challenge of bioinformation integration.

The range of open-source software packages includes titles such as Bioconductor, BioPerl, Biopython, BioJava, BioJS, BioRuby, Bioclipse, EMBOSS, .NET Bio, Orange with its bioinformatics add-on, Apache Taverna, UGENE and GenoCAD. To maintain this tradition and create further opportunities, the non-profit Open Bioinformatics Foundation[49] have supported the annual Bioinformatics Open Source Conference (BOSC) since 2000.[50]

An alternative method to build public bioinformatics databases is to use the MediaWiki engine with the WikiOpener extension. This system allows the database to be accessed and updated by all experts in the field.[51]

Web services in bioinformatics

SOAP- and REST-based interfaces have been developed for a wide variety of bioinformatics applications allowing an application running on one computer in one part of the world to use algorithms, data and computing resources on servers in other parts of the world. The main advantages derive from the fact that end users do not have to deal with software and database maintenance overheads.

Basic bioinformatics services are classified by the EBI into three categories: SSS (Sequence Search Services), MSA (Multiple Sequence Alignment), and BSA (Biological Sequence Analysis).[52] The availability of these service-oriented bioinformatics resources demonstrate the applicability of web-based bioinformatics solutions, and range from a collection of standalone tools with a common data format under a single, standalone or web-based interface, to integrative, distributed and extensible bioinformatics workflow management systems.

Bioinformatics workflow management systems

A bioinformatics workflow management system is a specialized form of a workflow management system designed specifically to compose and execute a series of computational or data manipulation steps, or a workflow, in a Bioinformatics application. Such systems are designed to

- provide an easy-to-use environment for individual application scientists themselves to create their own workflows,

- provide interactive tools for the scientists enabling them to execute their workflows and view their results in real-time,

- simplify the process of sharing and reusing workflows between the scientists, and

- enable scientists to track the provenance of the workflow execution results and the workflow creation steps.

Some of the platforms giving this service: Galaxy, Kepler, Taverna, UGENE, Anduril, HIVE.

BioCompute and BioCompute Objects

In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration sponsored a conference held at the National Institutes of Health Bethesda Campus to discuss reproducibility in bioinformatics.[53] Over the next three years, a consortium of stakeholders met regularly to discuss what would become BioCompute paradigm.[54] These stakeholders included representatives from government, industry, and academic entities. Session leaders represented numerous branches of the FDA and NIH Institutes and Centers, non-profit entities including the Human Variome Project and the European Federation for Medical Informatics, and research institutions including Stanford, the New York Genome Center, and the George Washington University.

It was decided that the BioCompute paradigm would be in the form of digital 'lab notebooks' which allow for the reproducibility, replication, review, and reuse, of bioinformatics protocols. This was proposed to enable greater continuity within a research group over the course of normal personnel flux while furthering the exchange of ideas between groups. The US FDA funded this work so that information on pipelines would be more transparent and accessible to their regulatory staff.[55]

In 2016, the group reconvened at the NIH in Bethesda and discussed the potential for a BioCompute Object, an instance of the BioCompute paradigm. This work was copied as both a "standard trial use" document and a preprint paper uploaded to bioRxiv. The BioCompute object allows for the JSON-ized record to be shared among employees, collaborators, and regulators.[56][57]

Education platforms

As well as in-person Masters degree courses being taught at many universities, the computational nature of bioinformtics lends it to computer-aided and online learning.[58][59] Software platforms designed to teach bioinformatics concepts and methods include Rosalind and online courses offered through the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics Training Portal. The Canadian Bioinformatics Workshops provides videos and slides from training workshops on their website under a Creative Commons license. The 4273π project or 4273pi project[60] also offers open source educational materials for free. The course runs on low cost Raspberry Pi computers and has been used to teach adults and school pupils.[61][62] 4273π is actively developed by a consortium of academics and research staff who have run research level bioinformatics using Raspberry Pi computers and the 4273π operating system.[63][64]

MOOC platforms also provide online certifications in bioinformatics and related disciplines, including Coursera's Bioinformatics Specialization (UC San Diego) and Genomic Data Science Specialization (Johns Hopkins) as well as EdX's Data Analysis for Life Sciences XSeries (Harvard).

Conferences

There are several large conferences that are concerned with bioinformatics. Some of the most notable examples are Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology (ISMB), European Conference on Computational Biology (ECCB), and Research in Computational Molecular Biology (RECOMB).

See also

- Biodiversity informatics

- Bioinformatics companies

- Computational biology

- Computational biomodeling

- Computational genomics

- Cyberbiosecurity

- Functional genomics

- Health informatics

- International Society for Computational Biology

- Jumping library

- List of bioinformatics institutions

- List of open-source bioinformatics software

- List of bioinformatics journals

- Metabolomics

- Nucleic acid sequence

- Phylogenetics

- Proteomics

- Gene Disease Database

References

- Lesk AM (26 July 2013). "Bioinformatics". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Sim AY, Minary P, Levitt M (June 2012). "Modeling nucleic acids". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 22 (3): 273–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.012. PMC 4028509. PMID 22538125.

- Dawson WK, Maciejczyk M, Jankowska EJ, Bujnicki JM (July 2016). "Coarse-grained modeling of RNA 3D structure". Methods. 103: 138–56. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.04.026. PMID 27125734.

- Kmiecik S, Gront D, Kolinski M, Wieteska L, Dawid AE, Kolinski A (July 2016). "Coarse-Grained Protein Models and Their Applications". Chemical Reviews. 116 (14): 7898–936. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00163. PMID 27333362.

- Wong KC (2016). Computational Biology and Bioinformatics: Gene Regulation. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 9781498724975.

- Joyce AP, Zhang C, Bradley P, Havranek JJ (January 2015). "Structure-based modeling of protein: DNA specificity". Briefings in Functional Genomics. 14 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1093/bfgp/elu044. PMC 4366589. PMID 25414269.

- Spiga E, Degiacomi MT, Dal Peraro M (2014). "New Strategies for Integrative Dynamic Modeling of Macromolecular Assembly". In Karabencheva-Christova T (ed.). Biomolecular Modelling and Simulations. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. Vol. 96. Academic Press. pp. 77–111. doi:10.1016/bs.apcsb.2014.06.008. ISBN 9780128000137. PMID 25443955.

- Ciemny M, Kurcinski M, Kamel K, Kolinski A, Alam N, Schueler-Furman O, Kmiecik S (August 2018). "Protein-peptide docking: opportunities and challenges". Drug Discovery Today. 23 (8): 1530–1537. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2018.05.006. PMID 29733895.

- Ouzounis, C. A.; Valencia, A. (2003). "Early bioinformatics: the birth of a discipline—a personal view". Bioinformatics. 19 (17): 2176–2190. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg309. PMID 14630646.

- Hogeweg P (March 2011). Searls DB (ed.). "The roots of bioinformatics in theoretical biology". PLOS Computational Biology. 7 (3): e1002021. Bibcode:2011PLSCB...7E2021H. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002021. PMC 3068925. PMID 21483479.

- Hesper B, Hogeweg P (1970). "Bio-informatica: een werkconcept". Kameleon. 1 (6): 28–29.

- Hesper B, Hogeweg P (2021). "Bio-informatics: a working concept. A translation of "Bio-informatica: een werkconcept" by B. Hesper and P. Hogeweg". arXiv:2111.11832v1 [q-bio.OT].

- Hogeweg P (1978). "Simulating the growth of cellular forms". Simulation. 31 (3): 90–96. doi:10.1177/003754977803100305. S2CID 61206099.

- Colby B (2022). "Whole Genome Sequencing Cost". Sequencing.com.

- Moody G (2004). Digital Code of Life: How Bioinformatics is Revolutionizing Science, Medicine, and Business. ISBN 978-0-471-32788-2.

- Dayhoff, M.O. (1966) Atlas of protein sequence and structure. National Biomedical Research Foundation, 215 pp.

- Eck RV, Dayhoff MO (April 1966). "Evolution of the structure of ferredoxin based on living relics of primitive amino Acid sequences". Science. 152 (3720): 363–6. Bibcode:1966Sci...152..363E. doi:10.1126/science.152.3720.363. PMID 17775169. S2CID 23208558.

- Johnson G, Wu TT (January 2000). "Kabat database and its applications: 30 years after the first variability plot". Nucleic Acids Research. 28 (1): 214–8. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.214. PMC 102431. PMID 10592229.

- Erickson JW, Altman GG (1979). "A Search for Patterns in the Nucleotide Sequence of the MS2 Genome". Journal of Mathematical Biology. 7 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1007/BF00275725. S2CID 85199492.

- Shulman MJ, Steinberg CM, Westmoreland N (February 1981). "The coding function of nucleotide sequences can be discerned by statistical analysis". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 88 (3): 409–20. Bibcode:1981JThBi..88..409S. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(81)90274-5. PMID 6456380.

- Xiong J (2006). Essential Bioinformatics. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 4. ISBN 978-0-511-16815-4 – via Internet Archive.

- Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, et al. (February 1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828. S2CID 4206886.

- Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL (January 2008). "GenBank". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D25-30. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm929. PMC 2238942. PMID 18073190.

- Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, et al. (July 1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800.

- Stein, Lincoln (2001). "Genome annotation: from sequence to biology". Nature. 2 (7): 493–503. doi:10.1038/35080529. PMID 11433356. S2CID 12044602.

- Erdin S, Lisewski AM, Lichtarge O (April 2011). "Protein function prediction: towards integration of similarity metrics". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 21 (2): 180–8. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2011.02.001. PMC 3120633. PMID 21353529.

- Carvajal-Rodríguez A (March 2010). "Simulation of genes and genomes forward in time". Current Genomics. 11 (1): 58–61. doi:10.2174/138920210790218007. PMC 2851118. PMID 20808525.

- Brown TA (2002). "Mutation, Repair and Recombination". Genomes (2nd ed.). Manchester (UK): Oxford.

- Carter NP, Fiegler H, Piper J (October 2002). "Comparative analysis of comparative genomic hybridization microarray technologies: report of a workshop sponsored by the Wellcome Trust". Cytometry. 49 (2): 43–8. doi:10.1002/cyto.10153. PMID 12357458.

- Chaudhari NM, Gupta VK, Dutta C (April 2016). "BPGA- an ultra-fast pan-genome analysis pipeline". Scientific Reports. 6: 24373. Bibcode:2016NatSR...624373C. doi:10.1038/srep24373. PMC 4829868. PMID 27071527.

- Aston KI (May 2014). "Genetic susceptibility to male infertility: news from genome-wide association studies". Andrology. 2 (3): 315–21. doi:10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00188.x. PMID 24574159. S2CID 206007180.

- Véron A, Blein S, Cox DG (2014). "Genome-wide association studies and the clinic: a focus on breast cancer". Biomarkers in Medicine. 8 (2): 287–96. doi:10.2217/bmm.13.121. PMID 24521025.

- Tosto G, Reitz C (October 2013). "Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer's disease: a review". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 13 (10): 381. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0381-0. PMC 3809844. PMID 23954969.

- Londin E, Yadav P, Surrey S, Kricka LJ, Fortina P (2013). "Use of linkage analysis, genome-wide association studies, and next-generation sequencing in the identification of disease-causing mutations". Pharmacogenomics. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1015. pp. 127–46. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-435-7_8. ISBN 978-1-62703-434-0. PMID 23824853.

- Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, Ramos EM, Mehta JP, Collins FS, Manolio TA (June 2009). "Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (23): 9362–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9362H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903103106. PMC 2687147. PMID 19474294.

- Hall LO (2010). "Finding the right genes for disease and prognosis prediction". 2010 International Conference on System Science and Engineering. System Science and Engineering (ICSSE),2010 International Conference. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1109/ICSSE.2010.5551766. ISBN 978-1-4244-6472-2. S2CID 21622726.

- Vazquez M, de la Torre V, Valencia A (27 December 2012). "Chapter 14: Cancer genome analysis". PLOS Computational Biology. 8 (12): e1002824. Bibcode:2012PLSCB...8E2824V. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002824. PMC 3531315. PMID 23300415.

- Hye-Jung EC, Jaswinder K, Martin K, Samuel AA, Marco AM (2014). "Second-Generation Sequencing for Cancer Genome Analysis". In Dellaire G, Berman JN, Arceci RJ (eds.). Cancer Genomics. Boston (US): Academic Press. pp. 13–30. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-396967-5.00002-5. ISBN 9780123969675.

- Grau J, Ben-Gal I, Posch S, Grosse I (July 2006). "VOMBAT: prediction of transcription factor binding sites using variable order Bayesian trees". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (Web Server issue): W529-33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl212. PMC 1538886. PMID 16845064.

- "The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "The human cell". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Thul PJ, Åkesson L, Wiking M, Mahdessian D, Geladaki A, Ait Blal H, et al. (May 2017). "A subcellular map of the human proteome". Science. 356 (6340): eaal3321. doi:10.1126/science.aal3321. PMID 28495876. S2CID 10744558.

- Ay F, Noble WS (September 2015). "Analysis methods for studying the 3D architecture of the genome". Genome Biology. 16 (1): 183. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0745-7. PMC 4556012. PMID 26328929.

- "AlphaFold". www.deepmind.com. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Jumper, John; Evans, Richard; Pritzel, Alexander; Green, Tim; Figurnov, Michael; Ronneberger, Olaf; Tunyasuvunakool, Kathryn; Bates, Russ; Žídek, Augustin; Potapenko, Anna; Bridgland, Alex; Meyer, Clemens; Kohl, Simon A. A.; Ballard, Andrew J.; Cowie, Andrew (August 2021). "Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold". Nature. 596 (7873): 583–589. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. ISSN 1476-4687.

- "AlphaFold Protein Structure Database". alphafold.ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Hoy JA, Robinson H, Trent JT, Kakar S, Smagghe BJ, Hargrove MS (August 2007). "Plant hemoglobins: a molecular fossil record for the evolution of oxygen transport". Journal of Molecular Biology. 371 (1): 168–79. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.029. PMID 17560601.

- Titz B, Rajagopala SV, Goll J, Häuser R, McKevitt MT, Palzkill T, Uetz P (May 2008). Hall N (ed.). "The binary protein interactome of Treponema pallidum--the syphilis spirochete". PLOS ONE. 3 (5): e2292. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2292T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002292. PMC 2386257. PMID 18509523.

- "Open Bioinformatics Foundation: About us". Official website. Open Bioinformatics Foundation. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- "Open Bioinformatics Foundation: BOSC". Official website. Open Bioinformatics Foundation. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Brohée S, Barriot R, Moreau Y (September 2010). "Biological knowledge bases using Wikis: combining the flexibility of Wikis with the structure of databases". Bioinformatics. 26 (17): 2210–1. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq348. PMID 20591906.

- Nisbet R, Elder IV J, Miner G (2009). "Bioinformatics". Handbook of Statistical Analysis and Data Mining Applications. Academic Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0080912035.

- Office of the Commissioner. "Advancing Regulatory Science – Sept. 24–25, 2014 Public Workshop: Next Generation Sequencing Standards". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Simonyan V, Goecks J, Mazumder R (2017). "Biocompute Objects-A Step towards Evaluation and Validation of Biomedical Scientific Computations". PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology. 71 (2): 136–146. doi:10.5731/pdajpst.2016.006734. PMC 5510742. PMID 27974626.

- Office of the Commissioner. "Advancing Regulatory Science – Community-based development of HTS standards for validating data and computation and encouraging interoperability". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Alterovitz G, Dean D, Goble C, Crusoe MR, Soiland-Reyes S, Bell A, et al. (December 2018). "Enabling precision medicine via standard communication of HTS provenance, analysis, and results". PLOS Biology. 16 (12): e3000099. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000099. PMC 6338479. PMID 30596645.

- BioCompute Object (BCO) project is a collaborative and community-driven framework to standardize HTS computational data. 1. BCO Specification Document: user manual for understanding and creating B., biocompute-objects, 3 September 2017

- Campbell, A. Malcolm (1 June 2003). "Public Access for Teaching Genomics, Proteomics, and Bioinformatics". Cell Biology Education. 2 (2): 98–111. doi:10.1187/cbe.03-02-0007. PMC 162192. PMID 12888845.

- Arenas, Miguel (September 2021). "General considerations for online teaching practices in bioinformatics in the time of COVID ‐19". Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 49 (5): 683–684. doi:10.1002/bmb.21558. ISSN 1470-8175. PMC 8426940. PMID 34231941.

- Barker D, Ferrier DE, Holland PW, Mitchell JB, Plaisier H, Ritchie MG, Smart SD (August 2013). "4273π: bioinformatics education on low cost ARM hardware". BMC Bioinformatics. 14: 243. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-14-243. PMC 3751261. PMID 23937194.

- Barker D, Alderson RG, McDonagh JL, Plaisier H, Comrie MM, Duncan L, et al. (2015). "University-level practical activities in bioinformatics benefit voluntary groups of pupils in the last 2 years of school". International Journal of STEM Education. 2 (17). doi:10.1186/s40594-015-0030-z.

- McDonagh JL, Barker D, Alderson RG (2016). "Bringing computational science to the public". SpringerPlus. 5 (259): 259. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-1856-7. PMC 4775721. PMID 27006868.

- Robson JF, Barker D (October 2015). "Comparison of the protein-coding gene content of Chlamydia trachomatis and Protochlamydia amoebophila using a Raspberry Pi computer". BMC Research Notes. 8 (561): 561. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1476-2. PMC 4604092. PMID 26462790.

- Wreggelsworth KM, Barker D (October 2015). "A comparison of the protein-coding genomes of two green sulphur bacteria, Chlorobium tepidum TLS and Pelodictyon phaeoclathratiforme BU-1". BMC Research Notes. 8 (565): 565. doi:10.1186/s13104-015-1535-8. PMC 4606965. PMID 26467441.

Further reading

- Sehgal et al. : Structural, phylogenetic and docking studies of D-amino acid oxidase activator(DAOA ), a candidate schizophrenia gene. Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling 2013 10 :3.

- Raul Isea The Present-Day Meaning Of The Word Bioinformatics, Global Journal of Advanced Research, 2015

- Achuthsankar S Nair Computational Biology & Bioinformatics – A gentle Overview, Communications of Computer Society of India, January 2007

- Aluru, Srinivas, ed. Handbook of Computational Molecular Biology. Chapman & Hall/Crc, 2006. ISBN 1-58488-406-1 (Chapman & Hall/Crc Computer and Information Science Series)

- Baldi, P and Brunak, S, Bioinformatics: The Machine Learning Approach, 2nd edition. MIT Press, 2001. ISBN 0-262-02506-X

- Barnes, M.R. and Gray, I.C., eds., Bioinformatics for Geneticists, first edition. Wiley, 2003. ISBN 0-470-84394-2

- Baxevanis, A.D. and Ouellette, B.F.F., eds., Bioinformatics: A Practical Guide to the Analysis of Genes and Proteins, third edition. Wiley, 2005. ISBN 0-471-47878-4

- Baxevanis, A.D., Petsko, G.A., Stein, L.D., and Stormo, G.D., eds., Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. Wiley, 2007. ISBN 0-471-25093-7

- Cristianini, N. and Hahn, M. Introduction to Computational Genomics, Cambridge University Press, 2006. (ISBN 9780521671910 |ISBN 0-521-67191-4)

- Durbin, R., S. Eddy, A. Krogh and G. Mitchison, Biological sequence analysis. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-62971-3

- Gilbert D (September 2004). "Bioinformatics software resources". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 5 (3): 300–4. doi:10.1093/bib/5.3.300. PMID 15383216.

- Keedwell, E., Intelligent Bioinformatics: The Application of Artificial Intelligence Techniques to Bioinformatics Problems. Wiley, 2005. ISBN 0-470-02175-6

- Kohane, et al. Microarrays for an Integrative Genomics. The MIT Press, 2002. ISBN 0-262-11271-X

- Lund, O. et al. Immunological Bioinformatics. The MIT Press, 2005. ISBN 0-262-12280-4

- Pachter, Lior and Sturmfels, Bernd. "Algebraic Statistics for Computational Biology" Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-85700-7

- Pevzner, Pavel A. Computational Molecular Biology: An Algorithmic Approach The MIT Press, 2000. ISBN 0-262-16197-4

- Soinov, L. Bioinformatics and Pattern Recognition Come Together Journal of Pattern Recognition Research (JPRR), Vol 1 (1) 2006 p. 37–41

- Stevens, Hallam, Life Out of Sequence: A Data-Driven History of Bioinformatics, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013, ISBN 9780226080208

- Tisdall, James. "Beginning Perl for Bioinformatics" O'Reilly, 2001. ISBN 0-596-00080-4

- Catalyzing Inquiry at the Interface of Computing and Biology (2005) CSTB report

- Calculating the Secrets of Life: Contributions of the Mathematical Sciences and computing to Molecular Biology (1995)

- Foundations of Computational and Systems Biology MIT Course

- Computational Biology: Genomes, Networks, Evolution Free MIT Course

External links

| Library resources about Bioinformatics |

The dictionary definition of bioinformatics at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of bioinformatics at Wiktionary Learning materials related to Bioinformatics at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Bioinformatics at Wikiversity Media related to Bioinformatics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bioinformatics at Wikimedia Commons- Bioinformatics Resource Portal (SIB)