Clitoris

The clitoris (/ˈklɪtərɪs/ (![]() listen) or /klɪˈtɔːrɪs/ (

listen) or /klɪˈtɔːrɪs/ (![]() listen)) is a female sex organ present in mammals, ostriches and a limited number of other animals. In humans, the visible portion – the glans – is at the front junction of the labia minora (inner lips), above the opening of the urethra. Unlike the penis, the male homologue (equivalent) to the clitoris, it usually does not contain the distal portion (or opening) of the urethra and is therefore not used for urination. In most species, the clitoris lacks any reproductive function. While few animals urinate through the clitoris or use it reproductively, the spotted hyena, which has an especially large clitoris, urinates, mates, and gives birth via the organ. Some other mammals, such as lemurs and spider monkeys, also have a large clitoris.[1]

listen)) is a female sex organ present in mammals, ostriches and a limited number of other animals. In humans, the visible portion – the glans – is at the front junction of the labia minora (inner lips), above the opening of the urethra. Unlike the penis, the male homologue (equivalent) to the clitoris, it usually does not contain the distal portion (or opening) of the urethra and is therefore not used for urination. In most species, the clitoris lacks any reproductive function. While few animals urinate through the clitoris or use it reproductively, the spotted hyena, which has an especially large clitoris, urinates, mates, and gives birth via the organ. Some other mammals, such as lemurs and spider monkeys, also have a large clitoris.[1]

| Clitoris | |

|---|---|

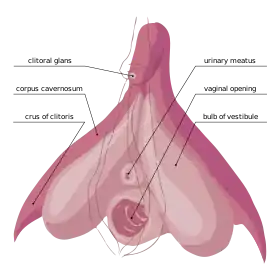

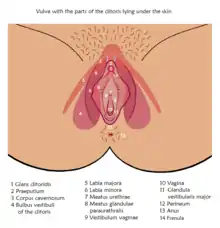

The internal anatomy of the human vulva, with the clitoral hood and labia minora indicated as lines. The clitoris extends from the visible portion to a point below the pubic bone. | |

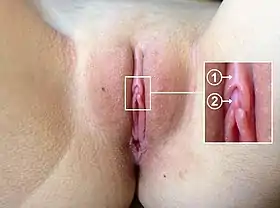

Location of (1) clitoral hood and (2) clitoral glans | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle |

| Artery | Dorsal artery of clitoris, deep artery of clitoris |

| Vein | Superficial dorsal veins of clitoris, deep dorsal vein of clitoris |

| Nerve | Dorsal nerve of clitoris |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Clitoris |

| MeSH | D002987 |

| TA98 | A09.2.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3565 |

| FMA | 9909 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The clitoris is the human female's most sensitive erogenous zone and generally the primary anatomical source of human female sexual pleasure.[2] In humans and other mammals, it develops from an outgrowth in the embryo called the genital tubercle. Initially undifferentiated, the tubercle develops into either a penis or a clitoris during the development of the reproductive system depending on exposure to androgens (which are primarily male hormones). The clitoris is a complex structure, and its size and sensitivity can vary. The glans (head) of the human clitoris is roughly the size and shape of a pea and is estimated to have more than 10,000 sensory nerve endings.[3]

Sexological, medical, and psychological debate have focused on the clitoris,[4] and it has been subject to social constructionist analyses and studies.[5] Such discussions range from anatomical accuracy, gender inequality, female genital mutilation, and orgasmic factors and their physiological explanation for the G-spot.[6] Although, in humans, the only known purpose of the clitoris is to provide sexual pleasure, whether the clitoris is vestigial, an adaptation, or serves a reproductive function has been debated.[7] Social perceptions of the clitoris include the significance of its role in female sexual pleasure, assumptions about its true size and depth, and varying beliefs regarding genital modification such as clitoris enlargement, clitoris piercing and clitoridectomy.[8] Genital modification may be for aesthetic, medical or cultural reasons.[8]

Knowledge of the clitoris is significantly impacted by cultural perceptions of the organ. Studies suggest that knowledge of its existence and anatomy is scant in comparison with that of other sexual organs and that more education about it could help alleviate social stigmas associated with the female body and female sexual pleasure, for example, that the clitoris and vulva in general are visually unappealing, that female masturbation is taboo, or that men should be expected to master and control women's orgasms.[9]

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary states that the word clitoris likely has its origin in the Ancient Greek κλειτορίς, kleitoris, perhaps derived from the verb κλείειν, kleiein, "to shut".[10] Clitoris is also Greek for the word key, "indicating that the ancient anatomists considered it the key" to female sexuality.[11][12] In addition to key, the Online Etymology Dictionary suggests other Greek candidates for the word's etymology include a noun meaning "latch" or "hook"; a verb meaning "to touch or titillate lasciviously", "to tickle" (one German synonym for the clitoris is der Kitzler, "the tickler"), although this verb is more likely derived from "clitoris"; and a word meaning "side of a hill", from the same root as "climax".[13] The Oxford English Dictionary also states that the shortened form "clit", the first occurrence of which was noted in the United States, has been used in print since 1958: until then, the common abbreviation was "clitty".[10]

The plural forms are clitorises in English and clitorides in Latin. The Latin genitive is clitoridis, as in "glans clitoridis". In medical and sexological literature, the clitoris is sometimes referred to as "the female penis" or pseudo-penis,[14] and the term clitoris is commonly used to refer to the glans alone;[15] partially because of this, there have been various terms for the organ that have historically confused its anatomy.

Structure

Development

In mammals, sexual differentiation is determined by the sperm that carries either an X or a Y (male) chromosome.[16] The Y chromosome contains a sex-determining gene (SRY) that encodes a transcription factor for the protein TDF (testis determining factor) and triggers the creation of testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone for the embryo's development into a male.[17][18] This differentiation begins about eight or nine weeks after conception.[17] Some sources state that it continues until the twelfth week,[19] while others state that it is clearly evident by the thirteenth week and that the sex organs are fully developed by the sixteenth week.[20]

The clitoris develops from a phallic outgrowth in the embryo called the genital tubercle. Initially undifferentiated, the tubercle develops into either a clitoris or penis during the development of the reproductive system depending on exposure to androgens (which are primarily male hormones). The clitoris forms from the same tissues that become the glans and shaft of the penis, and this shared embryonic origin makes these two organs homologous (different versions of the same structure).[21]

If exposed to testosterone, the genital tubercle elongates to form the penis. By fusion of the urogenital folds – elongated spindle-shaped structures that contribute to the formation of the urethral groove on the belly aspect of the genital tubercle – the urogenital sinus closes completely and forms the spongy urethra, and the labioscrotal swellings unite to form the scrotum.[21] In the absence of testosterone, the genital tubercle allows for formation of the clitoris; the initially rapid growth of the phallus gradually slows and the clitoris is formed. The urogenital sinus persists as the vestibule of the vagina, the two urogenital folds form the labia minora, and the labioscrotal swellings enlarge to form the labia majora, completing the female genitalia.[21] A rare condition that can develop from higher than average androgen exposure is clitoromegaly.[22]

General

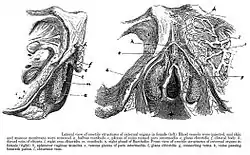

The clitoris contains external and internal components. It consists of the glans, the body (which is composed of two erectile structures known as the corpora cavernosa), and two crura ("legs"). It has a hood formed by the labia minora (inner lips). It also has vestibular or clitoral bulbs. The frenulum of clitoris is a frenulum on the undersurface of the glans and is created by the two medial parts of the labia minora.[23] The clitoral body may be referred to as the shaft (or internal shaft), while the length of the clitoris between the glans and the body may also be referred to as the shaft. The shaft supports the glans, and its shape can be seen and felt through the clitoral hood.[24]

Research indicates that clitoral tissue extends into the vagina's anterior wall.[25] Şenaylı et al. said that the histological evaluation of the clitoris, "especially of the corpora cavernosa, is incomplete because for many years the clitoris was considered a rudimentary and nonfunctional organ." They added that Baskin and colleagues examined the clitoris's masculinization after dissection and using imaging software after Masson chrome staining, put the serial dissected specimens together; this revealed that the nerves of the clitoris surround the whole clitoral body (corpus).[26]

The clitoris, vestibular bulbs, labia minora, and urethra involve two histologically distinct types of vascular tissue (tissue related to blood vessels), the first of which is trabeculated, erectile tissue innervated by the cavernous nerves. The trabeculated tissue has a spongy appearance; along with blood, it fills the large, dilated vascular spaces of the clitoris and the bulbs. Beneath the epithelium of the vascular areas is smooth muscle.[27] As indicated by Yang et al.'s research, it may also be that the urethral lumen (the inner open space or cavity of the urethra), which is surrounded by spongy tissue, has tissue that "is grossly distinct from the vascular tissue of the clitoris and bulbs, and on macroscopic observation, is paler than the dark tissue" of the clitoris and bulbs.[28] The second type of vascular tissue is non-erectile, which may consist of blood vessels that are dispersed within a fibrous matrix and have only a minimal amount of smooth muscle.[27]

Glans and body

Highly innervated, the glans exists at the tip of the clitoral body as a fibro-vascular cap[27] and is usually the size and shape of a pea, although it is sometimes much larger or smaller. The clitoral glans, or the entire clitoris, is estimated to have more than 10,000 sensory nerve endings.[3] Research conflicts on whether or not the glans is composed of erectile or non-erectile tissue. Although the clitoral body becomes engorged with blood upon sexual arousal, erecting the clitoral glans, some sources describe the clitoral glans and labia minora as composed of non-erectile tissue; this is especially the case for the glans.[15][27] They state that the clitoral glans and labia minora have blood vessels that are dispersed within a fibrous matrix and have only a minimal amount of smooth muscle,[27] or that the clitoral glans is "a midline, densely neural, non-erectile structure".[15]

Other descriptions of the glans assert that it is composed of erectile tissue and that erectile tissue is present within the labia minora.[29] The glans may be noted as having glandular vascular spaces that are not as prominent as those in the clitoral body, with the spaces being separated more by smooth muscle than in the body and crura.[28] Adipose tissue is absent in the labia minora, but the organ may be described as being made up of dense connective tissue, erectile tissue and elastic fibers.[29]

The clitoral body forms a wishbone-shaped structure containing the corpora cavernosa – a pair of sponge-like regions of erectile tissue that contain most of the blood in the clitoris during clitoral erection. The two corpora forming the clitoral body are surrounded by thick fibro-elastic tunica albuginea, literally meaning "white covering", connective tissue. These corpora are separated incompletely from each other in the midline by a fibrous pectiniform septum – a comblike band of connective tissue extending between the corpora cavernosa.[26][27]

The clitoral body extends up to several centimeters before reversing direction and branching, resulting in an inverted "V" shape that extends as a pair of crura ("legs").[30] The crura are the proximal portions of the arms of the wishbone. Ending at the glans of the clitoris, the tip of the body bends anteriorly away from the pubis.[28] Each crus (singular form of crura) is attached to the corresponding ischial ramus – extensions of the copora beneath the descending pubic rami.[26][27] Concealed behind the labia minora, the crura end with attachment at or just below the middle of the pubic arch.[N 1][32] Associated are the urethral sponge, perineal sponge, a network of nerves and blood vessels, the suspensory ligament of the clitoris, muscles and the pelvic floor.[27][33]

There is no identified correlation between the size of the clitoral glans, or clitoris as a whole, and a woman's age, height, weight, use of hormonal contraception, or being post-menopausal, although women who have given birth may have significantly larger clitoral measurements.[34] Centimeter (cm) and millimeter (mm) measurements of the clitoris show variations in its size. The clitoral glans has been cited as typically varying from 2 mm to 1 cm and usually being estimated at 4 to 5 mm in both the transverse and longitudinal planes.[35]

A 1992 study concluded that the total clitoral length, including glans and body, is 16.0 ± 4.3 mm (0.63 ± 0.17 in), where 16 mm (0.63 in) is the mean and 4.3 mm (0.17 in) is the standard deviation.[36] Concerning other studies, researchers from the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Obstetric Hospital in London measured the labia and other genital structures of 50 women from the age of 18 to 50, with a mean age of 35.6., from 2003 to 2004, and the results given for the clitoral glans were 3–10 mm for the range and 5.5 [1.7] mm for the mean.[37] Other research indicates that the clitoral body can measure 5–7 centimetres (2.0–2.8 in) in length, while the clitoral body and crura together can be 10 centimetres (3.9 in) or more in length.[27]

Hood

The clitoral hood projects at the front of the labia commissure, where the edges of the labia majora (outer lips) meet at the base of the pubic mound; it is partially formed by fusion of the upper part of the external folds of the labia minora (inner lips) and covers the glans and external shaft.[38] There is considerable variation in how much of the glans protrudes from the hood and how much is covered by it, ranging from completely covered to fully exposed,[36] and tissue of the labia minora also encircles the base of the glans.[39]

Bulbs

The vestibular bulbs are more closely related to the clitoris than the vestibule because of the similarity of the trabecular and erectile tissue within the clitoris and bulbs, and the absence of trabecular tissue in other genital organs, with the erectile tissue's trabecular nature allowing engorgement and expansion during sexual arousal.[27][39] The vestibular bulbs are typically described as lying close to the crura on either side of the vaginal opening; internally, they are beneath the labia majora. When engorged with blood, they cuff the vaginal opening and cause the vulva to expand outward.[27] Although a number of texts state that they surround the vaginal opening, Ginger et al. state that this does not appear to be the case and tunica albuginea does not envelop the erectile tissue of the bulbs.[27] In Yang et al.'s assessment of the bulbs' anatomy, they conclude that the bulbs "arch over the distal urethra, outlining what might be appropriately called the 'bulbar urethra' in women."[28]

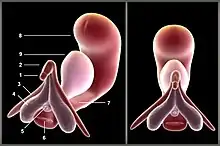

Homology

The clitoris and penis are generally the same anatomical structure, although the distal portion (or opening) of the urethra is absent in the clitoris of humans and most other animals. The idea that males have clitorises was suggested in 1987 by researcher Josephine Lowndes Sevely, who theorized that the male corpora cavernosa (a pair of sponge-like regions of erectile tissue which contain most of the blood in the penis during penile erection) are the true counterpart of the clitoris. She argued that "the male clitoris" is directly beneath the rim of the glans penis, where the frenulum of prepuce of the penis (a fold of the prepuce) is located, and proposed that this area be called the "Lownde's crown". Her theory and proposal, though acknowledged in anatomical literature, did not materialize in anatomy books.[40] Modern anatomical texts show that the clitoris displays a hood that is the equivalent of the penis's foreskin, which covers the glans. It also has a shaft that is attached to the glans. The male corpora cavernosa are homologous to the corpus cavernosum clitoridis (the female cavernosa), the bulb of penis is homologous to the vestibular bulbs beneath the labia minora, the scrotum is homologous to the labia majora, and the penile urethra and part of the skin of the penis is homologous to the labia minora.[41]

Upon anatomical study, the penis can be described as a clitoris that has been mostly pulled out of the body and grafted on top of a significantly smaller piece of spongiosum containing the urethra.[41] With regard to nerve endings, the human clitoris's estimated more than 10,000 (for its glans or clitoral body as a whole) is commonly cited as being twice as many as the nerve endings found in the human penis (for its glans or body as a whole) and as more than any other part of the human body.[3] These reports sometimes conflict with other sources on clitoral anatomy or those concerning the nerve endings in the human penis. For example, while some sources estimate that the human penis has 4,000 nerve endings,[42] other sources state that the glans or the entire penile structure have the same amount of nerve endings as the clitoral glans[43] or discuss whether the uncircumcised penis has thousands more than the circumcised penis or is generally more sensitive.[44][45]

Some sources state that in contrast to the glans penis, the clitoral glans lacks smooth muscle within its fibrovascular cap and is thus differentiated from the erectile tissues of the clitoris and bulbs; additionally, bulb size varies and may be dependent on age and estrogenization.[27] While the bulbs are considered the equivalent of the male spongiosum, they do not completely encircle the urethra.[27]

The thin corpus spongiosum of the penis runs along the underside of the penile shaft, enveloping the urethra, and expands at the end to form the glans. It partially contributes to erection, which are primarily caused by the two corpora cavernosa that comprise the bulk of the shaft; like the female cavernosa, the male cavernosa soak up blood and become erect when sexually excited.[46] The male corpora cavernosa taper off internally on reaching the spongiosum head.[46] With regard to the Y-shape of the cavernosa – crown, body, and legs – the body accounts for much more of the structure in men, and the legs are stubbier; typically, the cavernosa are longer and thicker in males than in females.[28][47]

Function

General

The clitoris has an abundance of nerve endings, and is the human female's most sensitive erogenous zone and generally the primary anatomical source of human female sexual pleasure.[2] When sexually stimulated, it may incite female sexual arousal. Sexual stimulation, including arousal, may result from mental stimulation, foreplay with a sexual partner, or masturbation, and can lead to orgasm.[48] The most effective sexual stimulation of the organ is usually manually or orally (cunnilingus), which is often referred to as direct clitoral stimulation; in cases involving sexual penetration, these activities may also be referred to as additional or assisted clitoral stimulation.[49]

Direct clitoral stimulation involves physical stimulation to the external anatomy of the clitoris – glans, hood, and the external shaft.[50] Stimulation of the labia minora (inner lips), due to its external connection with the glans and hood, may have the same effect as direct clitoral stimulation.[51] Though these areas may also receive indirect physical stimulation during sexual activity, such as when in friction with the labia majora (outer lips),[52] indirect clitoral stimulation is more commonly attributed to penile-vaginal penetration.[53][54] Penile-anal penetration may also indirectly stimulate the clitoris by the shared sensory nerves (especially the pudendal nerve, which gives off the inferior anal nerves and divides into two terminal branches: the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris).[55]

Due to the glans's high sensitivity, direct stimulation to it is not always pleasurable; instead, direct stimulation to the hood or the areas near the glans is often more pleasurable, with the majority of women preferring to use the hood to stimulate the glans, or to have the glans rolled between the lips of the labia, for indirect touch.[56] It is also common for women to enjoy the shaft of the clitoris being softly caressed in concert with occasional circling of the clitoral glans. This might be with or without manual penetration of the vagina, while other women enjoy having the entire area of the vulva caressed.[57] As opposed to use of dry fingers, stimulation from fingers that have been well-lubricated, either by vaginal lubrication or a personal lubricant, is usually more pleasurable for the external anatomy of the clitoris.[58][59]

As the clitoris's external location does not allow for direct stimulation by sexual penetration, any external clitoral stimulation while in the missionary position usually results from the pubic bone area, the movement of the groins when in contact. As such, some couples may engage in the woman-on-top position or the coital alignment technique, a sex position combining the "riding high" variation of the missionary position with pressure-counterpressure movements performed by each partner in rhythm with sexual penetration, to maximize clitoral stimulation.[60][61] Lesbian couples may engage in tribadism for ample clitoral stimulation or for mutual clitoral stimulation during whole-body contact.[N 2][63][64] Pressing the penis in a gliding or circular motion against the clitoris (intercrural sex), or stimulating it by movement against another body part, may also be practiced.[65][66] A vibrator (such as a clitoral vibrator), dildo or other sex toy may be used.[65][67] Other women stimulate the clitoris by use of a pillow or other inanimate object, by a jet of water from the faucet of a bathtub or shower, or by closing their legs and rocking.[68][69][70]

During sexual arousal, the clitoris and the whole of the genitalia engorge and change color as the erectile tissues fill with blood (vasocongestion), and the individual experiences vaginal contractions.[71] The ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus muscles, which insert into the corpora cavernosa, contract and compress the dorsal vein of the clitoris (the only vein that drains the blood from the spaces in the corpora cavernosa), and the arterial blood continues a steady flow and having no way to drain out, fills the venous spaces until they become turgid and engorged with blood. This is what leads to clitoral erection.[11][72]

The clitoral glans doubles in diameter upon arousal and upon further stimulation, becomes less visible as it is covered by the swelling of tissues of the clitoral hood.[71][73] The swelling protects the glans from direct contact, as direct contact at this stage can be more irritating than pleasurable.[73][74] Vasocongestion eventually triggers a muscular reflex, which expels the blood that was trapped in surrounding tissues, and leads to an orgasm.[75] A short time after stimulation has stopped, especially if orgasm has been achieved, the glans becomes visible again and returns to its normal state,[76] with a few seconds (usually 5–10) to return to its normal position and 5–10 minutes to return to its original size.[N 3][73][78] If orgasm is not achieved, the clitoris may remain engorged for a few hours, which women often find uncomfortable.[60] Additionally, the clitoris is very sensitive after orgasm, making further stimulation initially painful for some women.[79]

Clitoral and vaginal orgasmic factors

General statistics indicate that 70–80 percent of women require direct clitoral stimulation (consistent manual, oral or other concentrated friction against the external parts of the clitoris) to reach orgasm.[N 4][N 5][N 6][83] Indirect clitoral stimulation (for example, via vaginal penetration) may also be sufficient for female orgasm.[N 7][15][85] The area near the entrance of the vagina (the lower third) contains nearly 90 percent of the vaginal nerve endings, and there are areas in the anterior vaginal wall and between the top junction of the labia minora and the urethra that are especially sensitive, but intense sexual pleasure, including orgasm, solely from vaginal stimulation is occasional or otherwise absent because the vagina has significantly fewer nerve endings than the clitoris.[86]

Prominent debate over the quantity of vaginal nerve endings began with Alfred Kinsey. Although Sigmund Freud's theory that clitoral orgasms are a prepubertal or adolescent phenomenon and that vaginal (or G-spot) orgasms are something that only physically mature females experience had been criticized before, Kinsey was the first researcher to harshly criticize the theory.[87][88] Through his observations of female masturbation and interviews with thousands of women,[89] Kinsey found that most of the women he observed and surveyed could not have vaginal orgasms,[90] a finding that was also supported by his knowledge of sex organ anatomy.[91] Scholar Janice M. Irvine stated that he "criticized Freud and other theorists for projecting male constructs of sexuality onto women" and "viewed the clitoris as the main center of sexual response". He considered the vagina to be "relatively unimportant" for sexual satisfaction, relaying that "few women inserted fingers or objects into their vaginas when they masturbated". Believing that vaginal orgasms are "a physiological impossibility" because the vagina has insufficient nerve endings for sexual pleasure or climax, he "concluded that satisfaction from penile penetration [is] mainly psychological or perhaps the result of referred sensation".[92]

Masters and Johnson's research, as well as Shere Hite's, generally supported Kinsey's findings about the female orgasm.[93] Masters and Johnson were the first researchers to determine that the clitoral structures surround and extend along and within the labia. They observed that both clitoral and vaginal orgasms have the same stages of physical response, and found that the majority of their subjects could only achieve clitoral orgasms, while a minority achieved vaginal orgasms. On that basis, they argued that clitoral stimulation is the source of both kinds of orgasms,[94] reasoning that the clitoris is stimulated during penetration by friction against its hood.[95] The research came at the time of the second-wave feminist movement, which inspired feminists to reject the distinction made between clitoral and vaginal orgasms.[87][96] Feminist Anne Koedt argued that because men "have orgasms essentially by friction with the vagina" and not the clitoral area, this is why women's biology had not been properly analyzed. "Today, with extensive knowledge of anatomy, with [C. Lombard Kelly], Kinsey, and Masters and Johnson, to mention just a few sources, there is no ignorance on the subject [of the female orgasm]," she stated in her 1970 article The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm. She added, "There are, however, social reasons why this knowledge has not been popularized. We are living in a male society which has not sought change in women's role."[87]

Supporting an anatomical relationship between the clitoris and vagina is a study published in 2005, which investigated the size of the clitoris; Australian urologist Helen O'Connell, described as having initiated discourse among mainstream medical professionals to refocus on and redefine the clitoris, noted a direct relationship between the legs or roots of the clitoris and the erectile tissue of the clitoral bulbs and corpora, and the distal urethra and vagina while using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology.[97][98] While some studies, using ultrasound, have found physiological evidence of the G-spot in women who report having orgasms during vaginal intercourse,[85] O'Connell argues that this interconnected relationship is the physiological explanation for the conjectured G-Spot and experience of vaginal orgasms, taking into account the stimulation of the internal parts of the clitoris during vaginal penetration. "The vaginal wall is, in fact, the clitoris," she said. "If you lift the skin off the vagina on the side walls, you get the bulbs of the clitoris – triangular, crescental masses of erectile tissue."[15] O'Connell et al., having performed dissections on the female genitals of cadavers and used photography to map the structure of nerves in the clitoris, made the assertion in 1998 that there is more erectile tissue associated with the clitoris than is generally described in anatomical textbooks and were thus already aware that the clitoris is more than just its glans.[99] They concluded that some females have more extensive clitoral tissues and nerves than others, especially having observed this in young cadavers compared to elderly ones,[99] and therefore whereas the majority of females can only achieve orgasm by direct stimulation of the external parts of the clitoris, the stimulation of the more generalized tissues of the clitoris via vaginal intercourse may be sufficient for others.[15]

French researchers Odile Buisson Fr and Pierre Foldès reported similar findings to that of O'Connell's. In 2008, they published the first complete 3D sonography of the stimulated clitoris and republished it in 2009 with new research, demonstrating the ways in which erectile tissue of the clitoris engorges and surrounds the vagina. On the basis of their findings, they argued that women may be able to achieve vaginal orgasm via stimulation of the G-spot, because the highly innervated clitoris is pulled closely to the anterior wall of the vagina when the woman is sexually aroused and during vaginal penetration. They assert that since the front wall of the vagina is inextricably linked with the internal parts of the clitoris, stimulating the vagina without activating the clitoris may be next to impossible. In their 2009 published study, the "coronal planes during perineal contraction and finger penetration demonstrated a close relationship between the root of the clitoris and the anterior vaginal wall". Buisson and Foldès suggested "that the special sensitivity of the lower anterior vaginal wall could be explained by pressure and movement of clitoris's root during a vaginal penetration and subsequent perineal contraction".[100][101]

Researcher Vincenzo Puppo, who, while agreeing that the clitoris is the center of female sexual pleasure and believing that there is no anatomical evidence of the vaginal orgasm, disagrees with O'Connell and other researchers' terminological and anatomical descriptions of the clitoris (such as referring to the vestibular bulbs as the "clitoral bulbs") and states that "the inner clitoris" does not exist because the penis cannot come in contact with the congregation of multiple nerves/veins situated until the angle of the clitoris, detailed by Kobelt, or with the roots of the clitoris, which do not have sensory receptors or erogenous sensitivity, during vaginal intercourse.[14] Puppo's belief contrasts the general belief among researchers that vaginal orgasms are the result of clitoral stimulation; they reaffirm that clitoral tissue extends, or is at least stimulated by its bulbs, even in the area most commonly reported to be the G-spot.[102]

The G-spot being analogous to the base of the male penis has additionally been theorized, with sentiment from researcher Amichai Kilchevsky that because female fetal development is the "default" state in the absence of substantial exposure to male hormones and therefore the penis is essentially a clitoris enlarged by such hormones, there is no evolutionary reason why females would have an entity in addition to the clitoris that can produce orgasms.[103] The general difficulty of achieving orgasms vaginally, which is a predicament that is likely due to nature easing the process of child bearing by drastically reducing the number of vaginal nerve endings,[104] challenge arguments that vaginal orgasms help encourage sexual intercourse in order to facilitate reproduction.[105][106] Supporting a distinct G-spot, however, is a study by Rutgers University, published in 2011, which was the first to map the female genitals onto the sensory portion of the brain; the scans indicated that the brain registered distinct feelings between stimulating the clitoris, the cervix and the vaginal wall – where the G-spot is reported to be – when several women stimulated themselves in a functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) machine.[101][107] Barry Komisaruk, head of the research findings, stated that he feels that "the bulk of the evidence shows that the G-spot is not a particular thing" and that it is "a region, it's a convergence of many different structures".[105]

Vestigiality, adaptionist and reproductive views

Whether the clitoris is vestigial, an adaptation, or serves a reproductive function has also been debated.[108][109] Geoffrey Miller stated that Helen Fisher, Meredith Small and Sarah Blaffer Hrdy "have viewed the clitoral orgasm as a legitimate adaptation in its own right, with major implications for female sexual behavior and sexual evolution".[110] Like Lynn Margulis and Natalie Angier, Miller believes, "The human clitoris shows no apparent signs of having evolved directly through male mate choice. It is not especially large, brightly colored, specifically shaped or selectively displayed during courtship." He contrasts this with other female species such as spider monkeys and spotted hyenas that have clitorises as long as their male counterparts. He said the human clitoris "could have evolved to be much more conspicuous if males had preferred sexual partners with larger brighter clitorises" and that "its inconspicuous design combined with its exquisite sensitivity suggests that the clitoris is important not as an object of male mate choice, but as a mechanism of female choice."[110]

While Miller stated that male scientists such as Stephen Jay Gould and Donald Symons "have viewed the female clitoral orgasm as an evolutionary side-effect of the male capacity for penile orgasm" and that they "suggested that clitoral orgasm cannot be an adaptation because it is too hard to achieve",[110] Gould acknowledged that "most female orgasms emanate from a clitoral, rather than vaginal (or some other), site" and that his nonadaptive belief "has been widely misunderstood as a denial of either the adaptive value of female orgasm in general, or even as a claim that female orgasms lack significance in some broader sense". He said that although he accepts that "clitoral orgasm plays a pleasurable and central role in female sexuality and its joys," "[a]ll these favorable attributes, however, emerge just as clearly and just as easily, whether the clitoral site of orgasm arose as a spandrel or an adaptation". He added that the "male biologists who fretted over [the adaptionist questions] simply assumed that a deeply vaginal site, nearer the region of fertilization, would offer greater selective benefit" due to their Darwinian, summum bonum beliefs about enhanced reproductive success.[111]

Similar to Gould's beliefs about adaptionist views and that "females grow nipples as adaptations for suckling, and males grow smaller unused nipples as a spandrel based upon the value of single development channels",[111] Elisabeth Lloyd suggested that there is little evidence to support an adaptionist account of female orgasm.[106][109] Meredith L. Chivers stated that "Lloyd views female orgasm as an ontogenetic leftover; women have orgasms because the urogenital neurophysiology for orgasm is so strongly selected for in males that this developmental blueprint gets expressed in females without affecting fitness" and this is similar to "males hav[ing] nipples that serve no fitness-related function."[109]

At the 2002 conference for Canadian Society of Women in Philosophy, Nancy Tuana argued that the clitoris is unnecessary in reproduction; she stated that it has been ignored because of "a fear of pleasure. It is pleasure separated from reproduction. That's the fear." She reasoned that this fear causes ignorance, which veils female sexuality.[112] O'Connell stated, "It boils down to rivalry between the sexes: the idea that one sex is sexual and the other reproductive. The truth is that both are sexual and both are reproductive." She reiterated that the vestibular bulbs appear to be part of the clitoris and that the distal urethra and vagina are intimately related structures, although they are not erectile in character, forming a tissue cluster with the clitoris that appears to be the location of female sexual function and orgasm.[15][28]

Clinical significance

Modification

Modifications to the clitoris can be intentional or unintentional. They include female genital mutilation (FGM), sex reassignment surgery (for trans men as part transitioning, which may also include clitoris enlargement), intersex surgery, and genital piercings.[26][113][114] Use of anabolic steroids by bodybuilders and other athletes can result in significant enlargement of the clitoris in concert with other masculinizing effects on their bodies.[115][116] Abnormal enlargement of the clitoris may also be referred to as clitoromegaly, but clitoromegaly is more commonly seen as a congenital anomaly of the genitalia.[22]

Those taking hormones or other medications as part of a transgender transition usually experience dramatic clitoral growth; individual desires and the difficulties of phalloplasty (construction of a penis) often result in the retention of the original genitalia with the enlarged clitoris as a penis analogue (metoidioplasty).[26][114] However, the clitoris cannot reach the size of the penis through hormones.[114] A surgery to add function to the clitoris, such as metoidioplasty, is an alternative to phalloplasty that permits retention of sexual sensation in the clitoris.[114]

In clitoridectomy, the clitoris may be removed as part of a radical vulvectomy to treat cancer such as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia; however, modern treatments favor more conservative approaches, as invasive surgery can have psychosexual consequences.[117] Clitoridectomy more often involves parts of the clitoris being partially or completely removed during FGM, which may be additionally known as female circumcision or female genital cutting (FGC).[118][119] Removing the glans of the clitoris does not mean that the whole structure is lost, since the clitoris reaches deep into the genitals.[15]

In reduction clitoroplasty, a common intersex surgery, the glans is preserved and parts of the erectile bodies are excised.[26] Problems with this technique include loss of sensation, loss of sexual function, and sloughing of the glans.[26] One way to preserve the clitoris with its innervations and function is to imbricate and bury the clitoral glans; however, Şenaylı et al. state that "pain during stimulus because of trapped tissue under the scarring is nearly routine. In another method, 50 percent of the ventral clitoris is removed through the level base of the clitoral shaft, and it is reported that good sensation and clitoral function are observed in follow up"; additionally, it has "been reported that the complications are from the same as those in the older procedures for this method".[26]

With regard to females who have the condition congenital adrenal hyperplasia, the largest group requiring surgical genital correction, researcher Atilla Şenaylı stated, "The main expectations for the operations are to create a normal female anatomy, with minimal complications and improvement of life quality." Şenaylı added that "[c]osmesis, structural integrity, and coital capacity of the vagina, and absence of pain during sexual activity are the parameters to be judged by the surgeon." (Cosmesis usually refers to the surgical correction of a disfiguring defect.) He stated that although "expectations can be standardized within these few parameters, operative techniques have not yet become homogeneous. Investigators have preferred different operations for different ages of patients".[26]

Gender assessment and surgical treatment are the two main steps in intersex operations. "The first treatments for clitoromegaly were simply resection of the clitoris. Later, it was understood that the clitoris glans and sensory input are important to facilitate orgasm," stated Atilla. The clitoral glans's epithelium "has high cutaneous sensitivity, which is important in sexual responses", and it is because of this that "recession clitoroplasty was later devised as an alternative, but reduction clitoroplasty is the method currently performed."[26]

What is often referred to as "clit piercing" is the more common (and significantly less complicated) clitoral hood piercing. Since clitoral piercing is difficult and very painful, piercing of the clitoral hood is more common than piercing the clitoral shaft, owing to the small percentage of people who are anatomically suited for it.[113] Clitoral hood piercings are usually channeled in the form of vertical piercings, and, to a lesser extent, horizontal piercings. The triangle piercing is a very deep horizontal hood piercing, and is done behind the clitoris as opposed to in front of it. For styles such as the Isabella, which pass through the clitoral shaft but are placed deep at the base, they provide unique stimulation and still require the proper genital build. The Isabella starts between the clitoral glans and the urethra, exiting at the top of the clitoral hood; this piercing is highly risky with regard to the damage that may occur because of intersecting nerves.[113]

Sexual disorders

Persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD) results in a spontaneous, persistent, and uncontrollable genital arousal in women, unrelated to any feelings of sexual desire.[120] Clitoral priapism, also known as clitorism, is a rare, potentially painful medical condition and is sometimes described as an aspect of PGAD.[120] With PGAD, arousal lasts for an unusually extended period of time (ranging from hours to days);[121] it can also be associated with morphometric and vascular modifications of the clitoris.[122]

Drugs may cause or affect clitoral priapism. The drug trazodone is known to cause male priapism as a side effect, but there is only one documented report that it may have caused clitoral priapism, in which case discontinuing the medication may be a remedy.[123] Additionally, nefazodone is documented to have caused clitoral engorgement, as distinct from clitoral priapism, in one case,[123] and clitoral priapism can sometimes start as a result of, or only after, the discontinuation of antipsychotics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).[124]

Because PGAD is relatively rare and, as its own concept apart from clitoral priapism, has only been researched since 2001, there is little research into what may cure or remedy the disorder.[120] In some recorded cases, PGAD was caused by, or caused, a pelvic arterial-venous malformation with arterial branches to the clitoris; surgical treatment was effective in these cases.[125]

In 2022, The New York Times reported several instance of women experiencing reduced clitoral sensitivity or inability to orgasm following various surgical procedures. The Times quoted several researchers who suggest that surgeon's lack of training in clitoral anatomy and nerve distribution may have been a factor.[126]

Society and culture

Ancient Greek–16th century knowledge and vernacular

With regard to historical and modern perceptions of the clitoris, the clitoris and the penis were considered equivalent by some scholars for more than 2,500 years in all respects except their arrangement.[127] Due to it being frequently omitted from, or misrepresented in, historical and contemporary anatomical texts, it was also subject to a continual cycle of male scholars claiming to have discovered it.[128] The ancient Greeks, ancient Romans, and Greek and Roman generations up to and throughout the Renaissance, were aware that male and female sex organs are anatomically similar,[129][130] but prominent anatomists such as Galen (129 – c. 200 AD) and Vesalius (1514–1564) regarded the vagina as the structural equivalent of the penis, except for being inverted; Vesalius argued against the existence of the clitoris in normal women, and his anatomical model described how the penis corresponds with the vagina, without a role for the clitoris.[131]

Ancient Greek and Roman sexuality additionally designated penetration as "male-defined" sexuality. The term tribas, or tribade, was used to refer to a woman or intersex individual who actively penetrated another person (male or female) through use of the clitoris or a dildo. As any sexual act was believed to require that one of the partners be "phallic" and that therefore sexual activity between women was impossible without this feature, mythology popularly associated lesbians with either having enlarged clitorises or as incapable of enjoying sexual activity without the substitution of a phallus.[132][133]

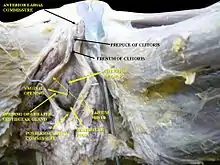

In 1545, Charles Estienne was the first writer to identify the clitoris in a work based on dissection, but he concluded that it had a urinary function.[15] Following this study, Realdo Colombo (also known as Matteo Renaldo Colombo), a lecturer in surgery at the University of Padua, Italy, published a book called De re anatomica in 1559, in which he describes the "seat of woman's delight".[134] In his role as researcher, Colombo concluded, "Since no one has discerned these projections and their workings, if it is permissible to give names to things discovered by me, it should be called the love or sweetness of Venus.", in reference to the mythological Venus, goddess of erotic love.[135][136] Colombo's claim was disputed by his successor at Padua, Gabriele Falloppio (discoverer of the fallopian tube), who claimed that he was the first to discover the clitoris. In 1561, Falloppio stated, "Modern anatomists have entirely neglected it ... and do not say a word about it ... and if others have spoken of it, know that they have taken it from me or my students." This caused an upset in the European medical community, and, having read Colombo's and Falloppio's detailed descriptions of the clitoris, Vesalius stated, "It is unreasonable to blame others for incompetence on the basis of some sport of nature you have observed in some women and you can hardly ascribe this new and useless part, as if it were an organ, to healthy women." He concluded, "I think that such a structure appears in hermaphrodites who otherwise have well formed genitals, as Paul of Aegina describes, but I have never once seen in any woman a penis (which Avicenna called albaratha and the Greeks called an enlarged nympha and classed as an illness) or even the rudiments of a tiny phallus."[137]

The average anatomist had difficulty challenging Galen's or Vesalius's research; Galen was the most famous physician of the Greek era and his works were considered the standard of medical understanding up to and throughout the Renaissance (i.e. for almost two thousand years),[130][131] and various terms being used to describe the clitoris seemed to have further confused the issue of its structure. In addition to Avicenna's naming it the albaratha or virga ("rod") and Colombo's calling it sweetness of Venus, Hippocrates used the term columella ("little pillar'"), and Albucasis, an Arabic medical authority, named it tentigo ("tension"). The names indicated that each description of the structures was about the body and glans of the clitoris but usually the glans.[15] It was additionally known to the Romans, who named it (vulgar slang) landica.[138] However, Albertus Magnus, one of the most prolific writers of the Middle Ages, felt that it was important to highlight "homologies between male and female structures and function" by adding "a psychology of sexual arousal" that Aristotle had not used to detail the clitoris. While in Constantine's treatise Liber de coitu, the clitoris is referred to a few times, Magnus gave an equal amount of attention to male and female organs.[15]

Like Avicenna, Magnus also used the word virga for the clitoris, but employed it for the male and female genitals; despite his efforts to give equal ground to the clitoris, the cycle of suppression and rediscovery of the organ continued, and a 16th-century justification for clitoridectomy appears to have been confused by hermaphroditism and the imprecision created by the word nymphae substituted for the word clitoris. Nymphotomia was a medical operation to excise an unusually large clitoris, but what was considered "unusually large" was often a matter of perception.[15] The procedure was routinely performed on Egyptian women,[139][140] due to physicians such as Jacques Daléchamps who believed that this version of the clitoris was "an unusual feature that occurred in almost all Egyptian women [and] some of ours, so that when they find themselves in the company of other women, or their clothes rub them while they walk or their husbands wish to approach them, it erects like a male penis and indeed they use it to play with other women, as their husbands would do ... Thus the parts are cut".[15]

17th century–present day knowledge and vernacular

Caspar Bartholin, a 17th-century Danish anatomist, dismissed Colombo's and Falloppio's claims that they discovered the clitoris, arguing that the clitoris had been widely known to medical science since the second century.[141] Although 17th-century midwives recommended to men and women that women should aspire to achieve orgasms to help them get pregnant for general health and well-being and to keep their relationships healthy,[130] debate about the importance of the clitoris persisted, notably in the work of Regnier de Graaf in the 17th century[39][142] and Georg Ludwig Kobelt in the 19th.[15]

Like Falloppio and Bartholin, De Graaf criticized Colombo's claim of having discovered the clitoris; his work appears to have provided the first comprehensive account of clitoral anatomy.[143] "We are extremely surprised that some anatomists make no more mention of this part than if it did not exist at all in the universe of nature," he stated. "In every cadaver we have so far dissected we have found it quite perceptible to sight and touch." De Graaf stressed the need to distinguish nympha from clitoris, choosing to "always give [the clitoris] the name clitoris" to avoid confusion; this resulted in frequent use of the correct name for the organ among anatomists, but considering that nympha was also varied in its use and eventually became the term specific to the labia minora, more confusion ensued.[15] Debate about whether orgasm was even necessary for women began in the Victorian era, and Freud's 1905 theory about the immaturity of clitoral orgasms (see above) negatively affected women's sexuality throughout most of the 20th century.[130][144]

Toward the end of World War I, a maverick British MP named Noel Pemberton Billing published an article entitled "The Cult of the Clitoris", furthering his conspiracy theories and attacking the actress Maud Allan and Margot Asquith, wife of the prime minister. The accusations led to a sensational libel trial, which Billing eventually won; Philip Hoare reports that Billing argued that "as a medical term, 'clitoris' would only be known to the 'initiated', and was incapable of corrupting moral minds".[145] Jodie Medd argues in regard to "The Cult of the Clitoris" that "the female nonreproductive but desiring body [...] simultaneously demands and refuses interpretative attention, inciting scandal through its very resistance to representation."[146]

From the 18th – 20th century, especially during the 20th, details of the clitoris from various genital diagrams presented in earlier centuries were omitted from later texts.[130][147] The full extent of the clitoris was alluded to by Masters and Johnson in 1966, but in such a muddled fashion that the significance of their description became obscured; in 1981, the Federation of Feminist Women's Health Clinics (FFWHC) continued this process with anatomically precise illustrations identifying 18 structures of the clitoris.[57][130] Despite the FFWHC's illustrations, Josephine Lowndes Sevely, in 1987, described the vagina as more of the counterpart of the penis.[148]

Concerning other beliefs about the clitoris, Hite (1976 and 1981) found that, during sexual intimacy with a partner, clitoral stimulation was more often described by women as foreplay than as a primary method of sexual activity, including orgasm.[149] Further, although the FFWHC's work significantly propelled feminist reformation of anatomical texts, it did not have a general impact.[98][150] Helen O'Connell's late 1990s research motivated the medical community to start changing the way the clitoris is anatomically defined.[98] O'Connell describes typical textbook descriptions of the clitoris as lacking detail and including inaccuracies, such as older and modern anatomical descriptions of the female human urethral and genital anatomy having been based on dissections performed on elderly cadavers whose erectile (clitoral) tissue had shrunk.[99] She instead credits the work of Georg Ludwig Kobelt as the most comprehensive and accurate description of clitoral anatomy.[15] MRI measurements, which provide a live and multi-planar method of examination, now complement the FFWHC's, as well as O'Connell's, research efforts concerning the clitoris, showing that the volume of clitoral erectile tissue is ten times that which is shown in doctors' offices and in anatomy text books.[39][98]

In Bruce Bagemihl's survey of The Zoological Record (1978–1997) – which contains over a million documents from over 6,000 scientific journals – 539 articles focusing on the penis were found, while 7 were found focusing on the clitoris.[151] In 2000, researchers Shirley Ogletree and Harvey Ginsberg concluded that there is a general neglect of the word clitoris in common vernacular. They looked at the terms used to describe genitalia in the PsycINFO database from 1887 to 2000 and found that penis was used in 1,482 sources, vagina in 409, while clitoris was only mentioned in 83. They additionally analyzed 57 books listed in a computer database for sex instruction. In the majority of the books, penis was the most commonly discussed body part – mentioned more than clitoris, vagina, and uterus put together. They last investigated terminology used by college students, ranging from Euro-American (76%/76%), Hispanic (18%/14%), and African American (4%/7%), regarding the students' beliefs about sexuality and knowledge on the subject. The students were overwhelmingly educated to believe that the vagina is the female counterpart of the penis. The authors found that the students' belief that the inner portion of the vagina is the most sexually sensitive part of the female body correlated with negative attitudes toward masturbation and strong support for sexual myths.[152][153]

.jpg.webp)

A 2005 study reported that, among a sample of undergraduate students, the most frequently cited sources for knowledge about the clitoris were school and friends, and that this was associated with the least tested knowledge. Knowledge of the clitoris by self-exploration was the least cited, but "respondents correctly answered, on average, three of the five clitoral knowledge measures". The authors stated that "[k]nowledge correlated significantly with the frequency of women's orgasm in masturbation but not partnered sex" and that their "results are discussed in light of gender inequality and a social construction of sexuality, endorsed by both men and women, that privileges men's sexual pleasure over women's, such that orgasm for women is pleasing, but ultimately incidental." They concluded that part of the solution to remedying "this problem" requires that males and females are taught more about the clitoris than is currently practiced.[154]

In May 2013, humanitarian group Clitoraid launched the first annual International Clitoris Awareness Week, from 6 to 12 May. Clitoraid spokesperson Nadine Gary stated that the group's mission is to raise public awareness about the clitoris because it has "been ignored, vilified, made taboo, and considered sinful and shameful for centuries".[155][156]

In 2016, Odile Fillod created a 3D printable, open source, full-size model of the clitoris, for use in a set of anti-sexist videos she had been commissioned to produce. Fillod was interviewed by Stephanie Theobald, whose article in The Guardian stated that the 3D model would be used for sex education in French schools, from primary to secondary level, from September 2016 onwards;[157] this was not the case, but the story went viral across the world.[158]

In a 2019 study, a questionnaire was administered to a sample of educational sciences postgraduate students to trace the level of their knowledge concerning the organs of the female and male reproductive system. The authors reported that about two-thirds of the students failed to name external female genitals, such as the clitoris and labia, even after detailed pictures were provided to them.[159] A 2022 analysis reported that the clitoris is mentioned in only one out of 113 Greek secondary education textbooks used in biology classes from 1870s to present.[160]

Contemporary art

In 2012, New York artist Sophia Wallace started work on a multimedia project to challenge misconceptions about the clitoris. Based on O'Connell's 1998 research, Wallace's work emphasizes the sheer scope and size of the human clitoris. She says that ignorance of this still seems to be pervasive in modern society. "It is a curious dilemma to observe the paradox that on the one hand the female body is the primary metaphor for sexuality, its use saturates advertising, art and the mainstream erotic imaginary," she said. "Yet, the clitoris, the true female sexual organ, is virtually invisible." The project is called Cliteracy and it includes a "clit rodeo", which is an interactive, climb-on model of a giant golden clitoris, including its inner parts, produced with the help of sculptor Kenneth Thomas. "It's been a showstopper wherever it's been shown. People are hungry to be able to talk about this," Wallace said. "I love seeing men standing up for the clit [...] Cliteracy is about not having one's body controlled or legislated [...] Not having access to the pleasure that is your birthright is a deeply political act."[161]

In 2016, another project started in New York, street art that has since spread to almost 100 cities: Clitorosity, a "community-driven effort to celebrate the full structure of the clitoris", combining chalk drawings and words to spark interaction and conversation with passers-by, which the team documents on social media.[162][163] In 2016, Lori-Malépart Traversy made an animated documentary about the unrecognized anatomy of the clitoris.[164]

In 2017, Alli Sebastian Wolf created a golden 100:1 scale model anatomical of a clitoris, called the Glitoris and said, she hopes knowledge of the clitoris will soon become so uncontroversial that making art about them would be as irrelevant as making art about penises.[165]

Other projects listed by the BBC include Clito Clito, body-positive jewellery made in Berlin; Clitorissima, a documentary intended to normalize mother-daughter conversations about the clitoris; and a ClitArt festival in London, encompassing spoken word performances as well as visual art.[163] French art collective Les Infemmes (a pun on "infamous" and "women") published a fanzine whose title can be translated as "The Clit Cheatsheet".[166]

Influence on female genital mutilation

Significant controversy surrounds female genital mutilation (FGM),[118][119] with the World Health Organization (WHO) being one of many health organizations that have campaigned against the procedures on behalf of human rights, stating that "FGM has no health benefits" and that it is "a violation of the human rights of girls and women" which "reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes".[119] The practice has existed at one point or another in almost all human civilizations,[139] most commonly to exert control over the sexual behavior, including masturbation, of girls and women, but also to change the clitoris's appearance.[119][140][167] Custom and tradition are the most frequently cited reasons for FGM, with some cultures believing that not performing it has the possibility of disrupting the cohesiveness of their social and political systems, such as FGM also being a part of a girl's initiation into adulthood. Often, a girl is not considered an adult in an FGM-practicing society unless she has undergone FGM,[119][140] and the "removal of the clitoris and labia – viewed by some as the male parts of a woman's body – is thought to enhance the girl's femininity, often synonymous with docility and obedience".[140]

Female genital mutilation is carried out in several societies, especially in Africa, with 85 percent of genital mutilations performed in Africa consisting of clitoridectomy or excision,[140][168] and to a lesser extent in other parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia, on girls from a few days old to mid-adolescent, often to reduce sexual desire in an effort to preserve vaginal virginity.[119][140][167] The practice of FGM has spread globally, as immigrants from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East bring the custom with them.[169] In the United States, it is sometimes practiced on girls born with a clitoris that is larger than usual.[118] Comfort Momoh, who specializes in the topic of FGM, states that FGM might have been "practiced in ancient Egypt as a sign of distinction among the aristocracy"; there are reports that traces of infibulation are on Egyptian mummies.[139] FGM is still routinely practiced in Egypt.[140][170] Greenberg et al. report that "one study found that 97% of married women in Egypt had had some form of genital mutilation performed."[170] Amnesty International estimated in 1997 that more than two million FGM procedures are performed every year.[140]

Other animals

General

Although the clitoris exists in all mammal species,[151] few detailed studies of the anatomy of the clitoris in non-humans exist.[171] The clitoris is especially developed in fossas,[172] apes, lemurs, moles,[173] and, like the penis in many non-human placental mammals, often contains a small bone. In females, this bone is known as the os clitoridis.[174] The clitoris exists in turtles,[175] ostriches,[176] crocodiles,[175] and in species of birds in which the male counterpart has a penis.[175] Some intersex female bears mate and give birth through the tip of the clitoris; these species are grizzly bears, brown bears, American black bears and polar bears. Although the bears have been described as having "a birth canal that runs through the clitoris rather than forming a separate vagina" (a feature that is estimated to make up 10 to 20 percent of the bears' population),[177] scientists state that female spotted hyenas are the only non-hermaphroditic female mammals devoid of an external vaginal opening, and whose sexual anatomy is distinct from usual intersex cases.[178]

Non-human primates

In spider monkeys, the clitoris is especially developed and has an interior passage, or urethra, that makes it almost identical to the penis, and it retains and distributes urine droplets as the female spider monkey moves around. Scholar Alan F. Dixson stated that this urine "is voided at the bases of the clitoris, flows down the shallow groove on its perineal surface, and is held by the skin folds on each side of the groove".[179] Because spider monkeys of South America have pendulous and erectile clitorises long enough to be mistaken for a penis, researchers and observers of the species look for a scrotum to determine the animal's sex; a similar approach is to identify scent-marking glands that may also be present on the clitoris.[180]

The clitoris erects in squirrel monkeys during dominance displays, which indirectly influences the squirrel monkeys' reproductive success.[181]

The clitoris of bonobos is larger and more externalized than in most mammals;[182] Natalie Angier said that a young adolescent "female bonobo is maybe half the weight of a human teenager, but her clitoris is three times bigger than the human equivalent, and visible enough to waggle unmistakably as she walks".[183] Female bonobos often engage in the practice of genital-genital (GG) rubbing, which is the non-human form of tribadism that human females engage in. Ethologist Jonathan Balcombe stated that female bonobos rub their clitorises together rapidly for ten to twenty seconds, and this behavior, "which may be repeated in rapid succession, is usually accompanied by grinding, shrieking, and clitoral engorgement"; he added that, on average, they engage in this practice "about once every two hours", and as bonobos sometimes mate face-to-face, "evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk has suggested that the position of the clitoris in bonobos and some other primates has evolved to maximize stimulation during sexual intercourse".[182]

Many strepsirrhine species exhibit elongated clitorises that are either fully or partially tunneled by the urethra, including mouse lemurs, dwarf lemurs, all Eulemur species, lorises and galagos.[184][185][186] Some of these species also exhibit a membrane seal across the vagina that closes the vaginal opening during the non-mating seasons, most notably mouse and dwarf lemurs.[184] The clitoral morphology of the ring-tailed lemur is the most well-studied. They are described as having "elongated, pendulous clitorises that are [fully] tunneled by a urethra". The urethra is surrounded by erectile tissue, which allows for significant swelling during breeding seasons, but this erectile tissue differs from the typical male corpus spongiosum.[187] Non-pregnant adult ring-tailed females do not show higher testosterone levels than males, but they do exhibit higher A4 and estrogen levels during seasonal aggression. During pregnancy, estrogen, A4, and testosterone levels are raised, but female fetuses are still "protected" from excess testosterone.[188] These "masculinized" genitalia are often found alongside other traits, such as female-dominated social groups, reduced sexual dimorphism that makes females the same size as males, and even ratios of sexes in adult populations.[188][189] This phenomenon that has been dubbed the "lemur syndrome".[190] A 2014 study of Eulemur masculinization proposed that behavioral and morphological masculinization in female lemuriformes is an ancestral trait that likely emerged after their split from lorisiformes.[189]

Spotted hyenas

While female spotted hyenas are sometimes referred to as hermaphrodites or as intersex,[180] and scientists of ancient and later historical times believed that they were hermaphrodites,[180][178][191] modern scientists do not refer to them as such.[178][192] That designation is typically reserved for those who simultaneously exhibit features of both sexes;[192] the genetic makeup of female spotted hyenas "are clearly distinct" from male spotted hyenas.[178][192]

Female spotted hyenas have a clitoris 90 percent as long and the same diameter as a male penis (171 millimeters long and 22 millimeters in diameter),[180] and this pseudo-penis's formation seems largely androgen-independent because it appears in the female fetus before differentiation of the fetal ovary and adrenal gland.[178] The spotted hyenas have a highly erectile clitoris, complete with a false scrotum; author John C. Wingfield stated that "the resemblance to male genitalia is so close that sex can be determined with confidence only by palpation of the scrotum".[181] The pseudo-penis can also be distinguished from the males' genitalia by its greater thickness and more rounded glans.[178] The female possesses no external vagina, as the labia are fused to form a pseudo-scrotum. In the females, this scrotum consists of soft adipose tissue.[181][178][193] Like male spotted hyenas with regard to their penises, the female spotted hyenas have small penile spines on the head of their clitorises, which scholar Catherine Blackledge said makes "the clitoris tip feel like soft sandpaper". She added that the clitoris "extends away from the body in a sleek and slender arc, measuring, on average, over 17 cm from root to tip. Just like a penis, [it] is fully erectile, raising its head in hyena greeting ceremonies, social displays, games of rough and tumble or when sniffing out peers".[194]

_(18006271698).jpg.webp)

Due to their higher levels of androgen exposure during fetal development, the female hyenas are significantly more muscular and aggressive than their male counterparts; social-wise, they are of higher rank than the males, being dominant or dominant and alpha, and the females who have been exposed to higher levels of androgen than average become higher-ranking than their female peers. Subordinate females lick the clitorises of higher-ranked females as a sign of submission and obedience, but females also lick each other's clitorises as a greeting or to strengthen social bonds; in contrast, while all males lick the clitorises of dominant females, the females will not lick the penises of males because males are considered to be of lowest rank.[193][196]

The urethra and vagina of the female spotted hyena exit through the clitoris, allowing the females to urinate, copulate and give birth through this organ.[181][178][194][197] This trait makes mating more laborious for the male than in other mammals, and also makes attempts to sexually coerce (physically force sexual activity on) females futile.[193] Joan Roughgarden, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist, said that because the hyena's clitoris is higher on the belly than the vagina in most mammals, the male hyena "must slide his rear under the female when mating so that his penis lines up with [her clitoris]". In an action similar to pushing up a shirtsleeve, the "female retracts the [pseudo-penis] on itself, and creates an opening into which the male inserts his own penis".[180] The male must practice this act, which can take a couple of months to successfully perform.[196] Female spotted hyenas exposed to larger doses of androgen have significantly damaged ovaries, making it difficult to conceive.[196] After giving birth, the pseudo-penis is stretched and loses much of its original aspects; it becomes a slack-walled and reduced prepuce with an enlarged orifice with split lips.[198] Approximately 15% of the females die during their first time giving birth, and over 60% of their species' firstborn young die.[180]

A 2006 Baskin et al. study concluded, "The basic anatomical structures of the corporeal bodies in both sexes of humans and spotted hyenas were similar. As in humans, the dorsal nerve distribution was unique in being devoid of nerves at the 12 o'clock position in the penis and clitoris of the spotted hyena" and that "[d]orsal nerves of the penis/clitoris in humans and male spotted hyenas tracked along both sides of the corporeal body to the corpus spongiosum at the 5 and 7 o'clock positions. The dorsal nerves penetrated the corporeal body and distally the glans in the hyena", and in female hyenas, "the dorsal nerves fanned out laterally on the clitoral body. Glans morphology was different in appearance in both sexes, being wide and blunt in the female and tapered in the male".[197]

Moles

Many species of Talpid moles exhibit peniform clitorises that are tunneled by the urethra and are found to have erectile tissue, most notably species from the Talpa genus found in Europe.[199] Unique to this clade are the presence of ovotestes, wherein the female ovary also is mostly made up of sterile testicular tissue that secretes testosterone with only a small portion of the gonad containing ovarian tissue. Genetic studies have revealed that females have an XX genotype and do not have any translocated Y-linked genes.[199] Detailed developmental studies of Talpa occidentalis have revealed that the female gonads develop in a "testis-like pattern". DMRT1, a gene that regulates development of Sertoli cells, was found to be expressed in female germ cells before meiosis, however no Sertoli cells were present in the fully-developed ovotestes. Additionally, the female germ cells only enter meiosis postnatally, a phenomenon that has not been found in any other eutherian mammal.[199] Phylogenetic analyses have suggested that, like in lemuroids, this trait must have evolved in a common ancestor of the clade, and has been "turned off and on" in different Talpid lineages.[200]

Female European moles are highly territorial and will not allow males in to their territory outside of breeding season, the probable cause of this behavior being the high levels of testosterone secreted by the female ovotestes.[199][200] During the non-breeding season, their vaginal opening is covered by skin, akin to the condition seen in mouse and dwarf lemurs.[199]

Cats, sheep and mice

Researchers studying the peripheral and central afferent pathways from the feline clitoris concluded that "afferent neurons projecting to the clitoris of the cat were identified by WGA-HRP tracing in the S1 and S2 dorsal root ganglia. An average of 433 cells were identified on each side of the animal. 85 percent and 15 percent of the labeled cells were located in the S1 and S2 dorsal root ganglia, respectively. The average cross sectional area of clitoral afferent neuron profiles was 1.479±627 μm2." They also stated that light "constant pressure on the clitoris produced an initial burst of single unit firing (maximum frequencies 170–255 Hz) followed by rapid adaptation and a sustained firing (maximum 40 Hz), which was maintained during the stimulation" and that further examination of tonic firing "indicate that the clitoris is innervated by mechano-sensitive myelinated afferent fibers in the pudental nerve which project centrally to the region of the dorsal commissure in the L7-S1 spinal cord".[201]

The external phenotype and reproductive behavior of 21 freemartin sheep and two male pseudohermaphrodite sheep were recorded with the aim of identifying any characteristics that could predict a failure to breed. The vagina's length and the size and shape of the vulva and clitoris were among the aspects analyzed. While the study reported that "a number of physical and behavioural abnormalities were detected," it also concluded that "the only consistent finding in all 23 animals was a short vagina which varied in length from 3.1 to 7.0 cm, compared with 10 to 14 cm in normal animals."[202]

In a study concerning the clitoral structure of mice, the mouse perineal urethra was documented as being surrounded by erectile tissue forming the bulbs of the clitoris.[171] The researchers stated, "In the mouse, as in human females, tissue organization in the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris is essentially similar to that of the penis except for the absence of a subalbugineal layer interposed between the tunica albuginea and the erectile tissue."[171]

See also

- Clitoral pump

- Clitoria, a type of tropical plant

- Clitoraid, a non-profit organization working against female genital mutilation

- The Evolution of Human Sexuality

Notes

- "The long, narrow crura arise from the inferior surface of the ischiopubic rami and fuse just below the middle of the pubic arch."[31]

- "A common variation is 'tribadism,' where two women lie face to face, one on top of the other. The genitals are pressed tightly together while the partners move in a grinding motion. Some rub their clitoris against their partner's pubic bone."[62]

- "Within a few seconds the clitoris returns to its normal position, and after 5 to 10 minutes shrinks to its normal size."[77]

- "Most women report the inability to achieve orgasm with vaginal intercourse and require direct clitoral stimulation ... About 20% have coital climaxes ..."[80]

- "Women rated clitoral stimulation as at least somewhat more important than vaginal stimulation in achieving orgasm; only about 20% indicated that they did not require additional clitoral stimulation during intercourse."[81]

- "a. The amount of time of sexual arousal needed to reach orgasm is variable – and usually much longer – in women than in men; thus, only 20–30% of women attain a coital climax. b. Many women (70–80%) require manual clitoral stimulation ..."[82]

- "In sum, it seems that approximately 25% of women always have orgasm with intercourse, while a narrow majority of women have orgasm with intercourse more than half the time ... According to the general statistics, cited in Chapter 2, [women who can consistently and easily have orgasms during unassisted intercourse] represent perhaps 20% of the adult female population, and thus cannot be considered representative."[84]

References

- Goodman 2009; Roughgarden 2004, pp. 37–40; Wingfield 2006, p. 2023

- Rodgers 2003, pp. 92–93; O'Connell, Sanjeevan & Hutson 2005, pp. 1189–1195; Greenberg, Bruess & Conklin 2010, p. 95; Weiten, Dunn & Hammer 2011, p. 386; Carroll 2012, pp. 110–111, 252

-

- White, Franny (27 October 2022). "Pleasure-producing human clitoris has more than 10,000 nerve fibers". News. Oregon Health & Science University. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

Blair Peters, M.D., an assistant professor of surgery in the OHSU School of Medicine and a plastic surgeon who specializes in gender-affirming care as part of the OHSU Transgender Health Program, led the research and presented the findings. Peters obtained clitoral nerve tissue from seven adult transmasculine volunteers who underwent gender-affirming genital surgery. Tissues were dyed and magnified 1,000 times under a microscope so individual nerve fibers could be counted with the help of image analysis software.

- Peters, B; Uloko, M; Isabey, P; How many Nerve Fibers Innervate the Human Clitoris? A Histomorphometric Evaluation of the Dorsal Nerve of the Clitoris 2 p.m. ET 27 October 2022, 23rd annual joint scientific meeting of Sexual Medicine Society of North America and International Society for Sexual Medicine

- DNC Cross Section.jpg