Mastocytoma

A mastocytoma or mast cell tumor is a type of round-cell tumor consisting of mast cells. It is found in humans and many animal species; it also can refer to an accumulation or nodule of mast cells that resembles a tumor.

| Mastocytoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Mast cell tumor |

| |

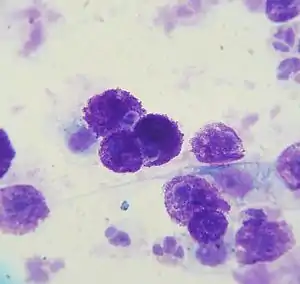

| Mast cell tumor cytology | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Mast cells originate from the bone marrow and are normally found throughout the connective tissue of the body as normal components of the immune system. As they release histamine, they are associated with allergic reactions. Mast cells also respond to tissue trauma. Mast cell granules contain histamine, heparin, platelet-activating factor, and other substances. Disseminated mastocytosis is rarely seen in young dogs and cats, while mast cell tumors are usually skin tumors in older dogs and cats. Although not always malignant, they do have the potential to be. Up to 25 percent of skin tumors in dogs are mast cell tumors,[1] with a similar number in cats.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Humans

When mastocytomas affect humans, they are typically found in skin.[3] They usually occur as a single lesion on the trunk or wrist. Although it is rare, mastocytomas are sometimes found in the lung.[3] It can also affect children.[4]

Other animals

Mast cell tumors are known among veterinary oncologists as 'the great pretenders' because their appearance can be varied, from a wart-like nodule to a soft subcutaneous lump (similar on palpation to a benign lipoma) to an ulcerated skin mass. Most mast cell tumors are small, raised lumps on the skin. They may be hairless, ulcerated, or itchy. They are usually solitary, but in about six percent of cases, there are multiple mast cell tumors[5] (especially in Boxers and Pugs).[6]

Manipulation of the tumor may result in redness and swelling from release of mast cell granules, also known as Darier's sign, and prolonged local hemorrhage. In rare cases, a highly malignant tumor is present, and signs may include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, and anemia. The presence of these signs usually indicates mastocytosis, which is the spread of mast cells throughout the body. Release of a large amount of histamine at one time can result in ulceration of the stomach and duodenum (present in up to 25 percent of cases)[6] or disseminated intravascular coagulation. When metastasis does occur, it is usually to the liver, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow.

Mast cell tumor on the side of a dog

Mast cell tumor on the side of a dog Mast cell tumor on the inner thigh of a dog

Mast cell tumor on the inner thigh of a dog Mast cell tumor of the paw

Mast cell tumor of the paw

Diagnosis

A needle aspiration biopsy of the tumor will typically show a large number of mast cells. This is sufficient to make the diagnosis of a mast cell tumor, although poorly differentiated mast cells may have few granules and thus are difficult to identify. The granules of the mast cell stain blue to dark purple with a Romanowsky stain, and the cells are medium-sized.[7] However, a surgical biopsy is required to find the grade of the tumor. The grade depends on how well the mast cells are differentiated, mitotic activity, location within the skin, invasiveness, and the presence of inflammation or necrosis.[8]

- Grade I – well differentiated and mature cells with a low potential for metastasis

- Grade II – intermediately differentiated cells with potential for local invasion and moderate metastatic behavior

- Grade III – undifferentiated, immature cells with a high potential for metastasis[1]

However, there is a significant amount of discordance between veterinary pathologists in assigning grades to mast cell tumors due to imprecise criteria.[9]

The disease is also staged according to the WHO system:

- Stage I - a single skin tumor with no spread to lymph nodes

- Stage II - a single skin tumor with spread to lymph nodes in the surrounding area

- Stage III - multiple skin tumors or a large tumor invading deep to the skin with or without lymph node involvement

- Stage IV – a tumor with metastasis to the spleen, liver, or bone marrow, or with the presence of mast cells in the blood[10]

X-rays, ultrasound, or lymph node, bone marrow, or organ biopsies may be necessary to stage the disease.

Treatment and prognosis

Removal of the mast cell tumor through surgery is the treatment of choice. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine, are given prior to surgery to protect against the effects of histamine released from the tumor. Wide margins (two to three centimeters) are required because of the tendency for the tumor cells to be spread out around the tumor. If complete removal is not possible due to the size or location, additional treatment, such as radiation therapy or chemotherapy, may be necessary. Prednisone is often used to shrink the remaining tumor portion. H2 blockers, such as cimetidine, protect against stomach damage from histamine. Vinblastine and lomustine are common chemotherapy agents used to treat mast cell tumors.[5]

Toceranib and masitinib, examples of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, are used in the treatment[11][12] of canine mast cell tumors. Both were recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[13][14] as dog-specific anticancer drugs.[15]

Grade I or II mast cell tumors that can be completely removed have a good prognosis. One study showed about 23 percent of incompletely removed grade II tumors recurred locally.[16] Any mast cell tumor found in the gastrointestinal tract, paw, or on the muzzle has a guarded prognosis. Previous beliefs that tumors in the groin or perineum carried a worse prognosis have been discounted.[17] Tumors that have spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body have a poor prognosis. Any dog showing symptoms of mastocytosis or with a grade III tumor has a poor prognosis. Dogs of the Boxer breed have a better than average prognosis because of the relatively benign behavior of their mast cell tumors.[10] Multiple tumors that are treated similarly to solitary tumors do not seem to have a worse prognosis.[18]

Mast cell tumors do not necessarily follow the histological prognosis. Further prognostic information can be provided by AgNOR stain of histological or cytological specimen.[19] Even then, there is a risk of unpredictable behavior.

Other animals

Mast cell tumors are an uncommon occurrence in horses. They usually occur as benign, solitary masses on the skin of the head, neck, trunk, and legs. Mineralization of the tumor is common.[20] In pigs and cattle, mast cell tumors are rare. They tend to be solitary and benign in pigs and multiple and malignant in cattle.[6] Mast cell tumors are found in the skin of cattle most commonly, but these may be metastases from tumors of the viscera.[21] Other sites in cattle include the spleen, muscle, gastrointestinal tract, omentum, and uterus.[22]

Dogs

Mast cell tumors mainly occur in older adult dogs, but have been known to occur on rare occasions in puppies. The following breeds are commonly affected by mast cell tumors:

Cats

Two types of mast cell tumors have been identified in cats, a mast cell type similar to dogs and a histiocytic type that appears as subcutaneous nodules and may resolve spontaneously. Young Siamese cats are at an increased risk for the histiocytic type,[2] although the mast cell type is the most common in all cats and is considered to be benign when confined to the skin.[6]

Mast cell tumors of the skin are usually located on the head or trunk.[24] Gastrointestinal and splenic involvement is more common in cats than in dogs; 50 percent of cases in dogs primarily involved the spleen or intestines.[25] Gastrointestinal mast cell tumors are most commonly found in the muscularis layer of the small intestine, but can also be found in the large intestine.[26] It is the third most common intestinal tumor in cats, after lymphoma and adenocarcinoma.[27]

Diagnosis and treatment are similar to that of the dog. Cases involving difficult to remove or multiple tumors have responded well to strontium-90 radiotherapy as an alternative to surgery.[28] The prognosis for solitary skin tumors is good, but guarded for tumors in other organs. Histological grading of tumors has little bearing on prognosis.[29]

References

- Brière C (2002). "Use of a reverse saphenous skin flap for the excision of a grade II mast cell tumor on the hind limb of a dog". Can Vet J. 43 (8): 620–2. PMC 339404. PMID 12170840.

- Johnson T, Schulman F, Lipscomb T, Yantis L (2002). "Histopathology and biologic behavior of pleomorphic cutaneous mast cell tumors in fifteen cats". Vet Pathol. 39 (4): 452–7. doi:10.1354/vp.39-4-452. PMID 12126148. S2CID 11717233.

- Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, eds. (2013). "Less Common Hematologic Malignancies". Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071748896.

- García Iglesias F, Sánchez García AM, García Lara GM. Mastocitoma solitario. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2014;16:35-7

- Moore, Anthony S. (2005). "Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumors in Dogs". Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- "Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumors". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- "Common Cytology Results". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- Vandis, Maria; Knoll, Joyce S. (March 2007). "Cytological examination of a cutaneous mast cell tumor in a boxer". Veterinary Medicine. Advanstar Communications. 102 (3): 165–168.

- Strefezzi R, Xavier J, Catão-Dias J (2003). "Morphometry of canine cutaneous mast cell tumors". Vet Pathol. 40 (3): 268–75. doi:10.1354/vp.40-3-268. PMID 12724567.

- Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06105-4.

- London CA, Malpas PB, Wood-Follis SL, et al. (June 2009). "Multi-center, Placebo-controlled, Double-blind, Randomized Study of Oral Toceranib Phosphate (SU11654), a Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, for the Treatment of Dogs with Recurrent (Either Local or Distant) Mast Cell Tumor Following Surgical Excision". Clin Cancer Res. 15 (11): 3856–65. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1860. PMID 19470739.

- Dubreuil P, Letard S, Ciufolini M, Gros L, Humbert M, Castéran N, Borge L, Hajem B, Lermet A, Sippl W, Voisset E, Arock M, Auclair C, Leventhal PS, Mansfield CD, Moussy A, Hermine O (September 2009). "Masitinib (AB1010), a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT". PLOS ONE. 4 (9): e7258. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007258. PMC 2746281. PMID 19789626.

- FDA NEWS RELEASE

- "KINAVET is Now Available from VetSource".

- CBS News FDA Approves First-Ever Dog Cancer Drug

- Séguin B, Besancon M, McCallan J, Dewe L, Tenwolde M, Wong E, Kent M (2006). "Recurrence rate, clinical outcome, and cellular proliferation indices as prognostic indicators after incomplete surgical excision of cutaneous grade II mast cell tumors: 28 dogs (1994–2002)". J Vet Intern Med. 20 (4): 933–40. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[933:RRCOAC]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16955819.

- Sfiligoi G, Rassnick K, Scarlett J, Northrup N, Gieger T (2005). "Outcome of dogs with mast cell tumors in the inguinal or perineal region versus other cutaneous locations: 124 cases (1990–2001)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 226 (8): 1368–74. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.226.1368. PMID 15844431.

- Mullins M, Dernell W, Withrow S, Ehrhart E, Thamm D, Lana S (2006). "Evaluation of prognostic factors associated with outcome in dogs with multiple cutaneous mast cell tumors treated with surgery with and without adjuvant treatment: 54 cases (1998–2004)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 228 (1): 91–5. doi:10.2460/javma.228.1.91. PMID 16426175.

- Scase T, Edwards D, Miller J, Henley W, Smith K, Blunden A, Murphy S (2006). "Canine mast cell tumors: correlation of apoptosis and proliferation markers with prognosis". J Vet Intern Med. 20 (1): 151–8. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(2006)20[151:CMCTCO]2.0.CO;2. hdl:10871/37694. PMID 16496935.

- Cole R, Chesen A, Pool R, Watkins J (2007). "Imaging diagnosis—equine mast cell tumor". Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 48 (1): 32–4. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.2007.00200.x. PMID 17236357.

- Smith B, Phillips L (2001). "Congenital mastocytomas in a Holstein calf". Can Vet J. 42 (8): 635–7. PMC 1476568. PMID 11519274.

- Ames T, O'Leary T (1984). "Mastocytoma in a cow: a case report". Can J Comp Med. 48 (1): 115–7. PMC 1236018. PMID 6424914.

- Miller D (1995). "The occurrence of mast cell tumors in young Shar-Peis". J Vet Diagn Invest. 7 (3): 360–363. doi:10.1177/104063879500700311. PMID 7578452.

- Litster A, Sorenmo K (2006). "Characterisation of the signalment, clinical and survival characteristics of 41 cats with mast cell neoplasia". J Feline Med Surg. 8 (3): 177–83. doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2005.12.005. PMID 16476559. S2CID 20724869.

- Takahashi T, Kadosawa T, Nagase M, Matsunaga S, Mochizuki M, Nishimura R, Sasaki N (2000). "Visceral mast cell tumors in dogs: 10 cases (1982–1997)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 216 (2): 222–6. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.216.222. PMID 10649758.

- "Gastrointestinal Neoplasia". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- Moriello, Karen A. (April 2007). "Clinical Snapshot". Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. Veterinary Learning Systems. 29 (4): 204.

- Turrel J, Farrelly J, Page R, McEntee M (2006). "Evaluation of strontium 90 irradiation in treatment of cutaneous mast cell tumors in cats: 35 cases (1992–2002)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 228 (6): 898–901. doi:10.2460/javma.228.6.898. PMID 16536702.

- Molander-McCrary H, Henry C, Potter K, Tyler J, Buss M (1998). "Cutaneous mast cell tumors in cats: 32 cases (1991–1994)". J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 34 (4): 281–4. doi:10.5326/15473317-34-4-281. PMID 9657159.