Subfornical organ

The subfornical organ (SFO) is one of the circumventricular organs of the brain.[1][2] Its name comes from its location on the ventral surface of the fornix near the interventricular foramina (foramina of Monro), which interconnect the lateral ventricles and the third ventricle. Like all circumventricular organs, the subfornical organ is well-vascularized, and like all circumventricular organs except the subcommissural organ, some SFO capillaries have fenestrations, which increase capillary permeability.[1][3][4] The SFO is considered a sensory circumventricular organ because it is responsive to a wide variety of hormones and neurotransmitters, as opposed to secretory circumventricular organs, which are specialized in the release of certain substances.[1][4][5]

| Subfornical organ | |

|---|---|

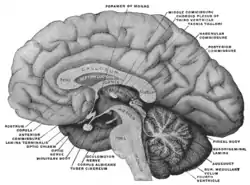

Medial aspect of a brain sectioned in the median sagittal plane. (Subfornical organ not labeled, but fornix and foramen of Monro are both labeled near the center.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | organum subfornicale |

| MeSH | D013356 |

| NeuroLex ID | nlx_anat_100314 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.412 A14.1.09.449 |

| TA2 | 5782 |

| FMA | 75260 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Anatomy

As noted above, capillaries in some subregions within the SFO are fenestrated,[6] and thus lack a blood-brain barrier. All circumventricular organs except the subcommissural organ contain fenestrated capillaries,[2] a feature that distinguishes them from most other parts of the brain.[7] The SFO can be divided into six anatomical zones based on its capillary topography: two zones in the coronal plane and four zones in the sagittal plane.[3] The central zone is composed of the glial cells, neuronal cell bodies and a high density of fenestrated capillaries.[8] Conversely, the rostral and caudal areas have a lower density of capillaries[8] and are mostly made of nerve fibers, with fewer neurons and glial cells seen in this area. Functionally, however, the SFO may be viewed in two portions, the dorsolateral peripheral division, and the ventromedial core segment.[9]

The subfornical organ contains endothelin receptors mediating vasoconstriction and high rates of glucose metabolism mediated by calcium channels.[10]

General function

The subfornical organ is active in many bodily processes,[1][5] including osmoregulation,[9] cardiovascular regulation,[9] and energy homeostasis.[1][5] Most of these processes involve fluid balance through the control of the release of certain hormones, particularly angiotensin or vasopressin.[5]

Cardiovascular regulation

The impact of the SFO on the cardiovascular system is mostly mediated through its influence on fluid balance.[1] The SFO plays a role in vasopressin regulation. Vasopressin is a hormone that, when bound to receptors in the kidneys, increases water retention by decreasing the amount of fluid transferred from blood to urine by the kidneys. This regulation of blood volume affects other aspects of the cardiovascular system. Increased or decreased blood volume influences blood pressure, which is regulated by baroreceptors, and can in turn affect the strength of ventricular contraction in the heart. Additional research has demonstrated that the subfornical organ may be an important intermediary through which leptin acts to maintain blood pressure within normal physiological limits via descending autonomic pathways associated with cardiovascular control.[1]

SFO neurons have also been experimentally shown to send efferent projections to regions involved in cardiovascular regulation including the lateral hypothalamus, with fibers terminating in the supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei, and the anteroventral 3rd ventricle (AV3V) with fibers terminating in the OVLT and the median preoptic area.[5]

Relationship with other circumventricular organs

Other circumventricular organs participating in systemic regulatory processes are the area postrema and the OVLT.[1][5][7] The OVLT and SFO are both interconnected with the nucleus medianus, and together these three structures comprise the so-called "AV3V" region – the region anterior and ventral to the third ventricle.[5] The AV3V region is important in the regulation of fluid and electrolyte balance, by controlling thirst, sodium excretion, blood volume regulation, and vasopressin secretion.[1][5] The SFO, area postrema, and OVLT have capillaries permeable to circulating hormonal signals, enabling these three circumventricular organs to have integrative roles in cardiovascular, electrolyte, and fluid regulation.[1][5][8]

Hormones and receptors

Neurons in the subfornical organ have receptors for many hormones that circulate in the blood but which do not cross the blood–brain barrier,[1] including angiotensin, atrial natriuretic peptide, endothelin and relaxin. The role of the SFO in angiotensin regulation is particularly important, as it is involved in communication with the nucleus medianus (also called the median preoptic nucleus). Some neurons in the SFO are osmoreceptors, being sensitive to the osmotic pressure of the blood. These neurons project to the supraoptic nucleus and paraventricular nucleus to regulate the activity of vasopressin-secreting neurons. These neurons also project to the nucleus medianus which is involved in controlling thirst. Thus, the subfornical organ is involved in fluid balance.

Other important hormones have been shown to excite the SFO, specifically serotonin, carbamylcholine (carbachol), and atropine. These neurotransmitters however seem to have an effect on deeper areas of the SFO than angiotensin, and antagonists of these hormones have been shown to also primarily effect the non-superficial regions of the SFO (other than atropine antagonists, which showed little effects). In this context, the superficial region is considered to be 15-55μm deep into the SFO, and the "deep" region anything below that.

From these reactions to certain hormones and other molecules, a model of the neuronal organization of the SFO is suggested in which angiotensin-sensitive neurons lying superficially are excited by substances borne by blood or cerebrospinal fluid, and synapse with deeper carbachol-sensitive neurons. The axons of these deep neurons pass out of the SFO in the columns and body of the fornix. Afferent fibers from the body and columns of the fornix polysynaptically excite both superficial and deep neurons. A recurrent inhibitory circuit is suggested on the output path.[5]

Genetics

The expression of various genes in the subfornical organ have been studied. For example, it was seen that water deprivation in rats led to an upregulation of the mRNA that codes for angiotensin II receptors, allowing for a lower angiotensin concentration in the blood that produce the "thirst" response. It also has been observed to be a site of thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1) production, a protein generally produced in the hypothalamus.[11]

Pathology

Hypertension

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is highly affected by the concentration of angiotensin. Injection of angiontensin has actually been long used to induce hypertension in animal test models to study the effects of various therapies and medications. In such experiments, it has been observed that an intact and functioning subfornical organ limits the increase in mean arterial pressure due to the increased angiotensin.[12]

Dehydration

As stated above, angiotensin receptors (AT1) have been shown to be upregulated due to water deprivation. These AT1 receptors have also shown an increased bonding with circulating angiotensin after water deprivation. These findings could indicate some sort of morphological change in the AT1 receptor, likely due to some signal protein modification of the AT1 receptor at a non-bonding site, leading to an increased affinity of the AT1 receptor for angiotensin bonding.[13]

Research

Feeding

Although generally viewed primarily as having roles in homeostasis and cardiovascular regulation, the subfornical organ has been thought to control feeding patterns through taking inputs from the blood (various peptides indicating satiety) and then stimulating hunger. It has been shown to induce drinking in rats as well as eating.[5]

References

- Gross, P. M; Weindl, A (1987). "Peering through the windows of the brain (review)". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 7 (6): 663–72. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.1987.120. PMID 2891718.

- Oldfield BJ, Mckinley MJ (1995). Paxinos G (ed.). The Rat Nervous System. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 391–403. ISBN 978-0-12-547635-5.

- Sposito NM, Gross PM (1987). "Topography and morphometry of capillaries in the rat subfornical organ". J Comp Neurol. 260 (1): 36–46. doi:10.1002/cne.902600104. PMID 3597833. S2CID 26102264.

- Miyata, S (2015). "New aspects in fenestrated capillary and tissue dynamics in the sensory circumventricular organs of adult brains". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 390. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00390. PMC 4621430. PMID 26578857.

- McKinley, Michael J.; Denton, Derek A.; Ryan, Philip J.; Yao, Song T.; Stefanidis, Aneta; Oldfield, Brian J. (14 March 2019). "From sensory circumventricular organs to cerebral cortex: Neural pathways controlling thirst and hunger". Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 31 (3): e12689. doi:10.1111/jne.12689. hdl:11343/285537. ISSN 0953-8194. PMID 30672620. S2CID 58947441.

- Shaver SW, Sposito NM, Gross PM (1990). "Quantitative fine structure of capillaries in subregions of the rat subfornical organ". J Comp Neurol. 294 (1): 145–52. doi:10.1002/cne.902940111. PMID 2324330. S2CID 38665940.

- Gross PM (1992). Circumventricular organ capillaries (Review). Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 91. pp. 219–33. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62338-9. ISBN 9780444814197. PMID 1410407.

- Gross PM (1991). "Morphology and physiology of capillary systems in subregions of the subfornical organ and area postrema". Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 69 (7): 1010–25. doi:10.1139/y91-152. PMID 1954559.

- Kawano, H.; Masuko, S. (2010). "Region-specific projections from the subfornical organ to the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus in the rat". Neuroscience. 169 (3): 1227–34. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.065. PMID 20678996. S2CID 29552630.

- Gross PM, Wainman DS, Chew BH, Espinosa FJ, Weaver DF (1993). "Calcium-mediated metabolic stimulation of neuroendocrine structures by intraventricular endothelin-1 in conscious rats". Brain Res. 606 (1): 135–42. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91581-c. PMID 8461995. S2CID 12713010.

- Son YJ, Hur MK, Ryu BJ, Park SK (2003). "TTF-1, a homeodomain-containing transcription factor, participates in the control of body fluid homeostasis by regulating angiotensinogen gene transcription in the rat subfornical organ". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (29): 27043–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M303157200. PMID 12730191.

- Bruner CA, Mangiopane ML, Fink GD (1985). "Subfornical organ. Does it protect against angiotensin II-induced hypertension in the rat?". Circ. Res. 56 (3): 462–6. doi:10.1161/01.res.56.3.462. PMID 3971518.

- Sanvitto GL, Jöhren O, Häuser W, Saavedra JM (July 1997). "Water deprivation upregulates ANG II AT1 binding and mRNA in rat subfornical organ and anterior pituitary". Am. J. Physiol. 273 (1 Pt 1): E156–63. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E156. PMID 9252492.