Yaws

Yaws is a tropical infection of the skin, bones, and joints caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum pertenue.[6][8] The disease begins with a round, hard swelling of the skin, 2 to 5 cm (0.79 to 1.97 in) in diameter.[6] The center may break open and form an ulcer.[6] This initial skin lesion typically heals after 3–6 months.[7] After weeks to years, joints and bones may become painful, fatigue may develop, and new skin lesions may appear.[6] The skin of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet may become thick and break open.[7] The bones (especially those of the nose) may become misshapen.[7] After 5 years or more, large areas of skin may die, leaving scars.[6]

| Yaws | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Frambesia tropica, thymosis, polypapilloma tropicum,[1] non-venereal endemic syphilis,[2] parangi and paru (Malay),[3] bouba (Spanish),[3] frambösie,[4] pian[5] (French),[3] frambesia (German),[3] bakataw (Maguindanaoan)[3] |

| |

| Nodules on the elbow resulting from a Treponema pallidum pertenue bacterial infection | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Hard swelling of the skin, ulcer, joint and bone pain[6] |

| Causes | Treponema pallidum pertenue spread by direct contact[7] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, blood antibody tests, polymerase chain reaction[7] |

| Prevention | Mass treatment[7] |

| Medication | Azithromycin, benzathine penicillin[7] |

| Frequency | 46,000–500,000[7][8] |

Yaws is spread by direct contact with the fluid from a lesion of an infected person.[7] The contact is usually of a nonsexual nature.[7] The disease is most common among children, who spread it by playing together.[6] Other related treponemal diseases are bejel (T. pallidum endemicum), pinta (T. carateum), and syphilis (T. p. pallidum).[7] Yaws is often diagnosed by the appearance of the lesions.[7] Blood antibody tests may be useful, but cannot separate previous from current infections.[7] Polymerase chain reaction is the most accurate method of diagnosis.[7]

No vaccine has yet been found.[9] Prevention is, in part, done by curing those who have the disease, thereby decreasing the risk of transmission.[7] Where the disease is common, treating the entire community is effective.[7] Improving cleanliness and sanitation also decreases spread.[7] Treatment is typically with antibiotics, including: azithromycin by mouth or benzathine penicillin by injection.[7] Without treatment, physical deformities occur in 10% of cases.[7]

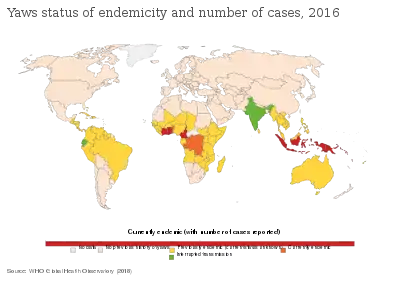

Yaws is common in at least 13 tropical countries as of 2012.[6][7] Almost 85% of infections occurred in three countries—Ghana, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands.[10] The disease only infects humans.[7] Efforts in the 1950s and 1960s by the World Health Organization decreased the number of cases by 95%.[7] Since then, cases have increased, but with renewed efforts to globally eradicate the disease by 2020.[7] In 1995, the number of people infected was estimated at more than 500,000.[8] In 2016, the number of reported cases was 59,000.[11] Although one of the first descriptions of the disease was made in 1679 by Willem Piso, archaeological evidence suggests that yaws may have been present among human ancestors as far back as 1.6 million years ago.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Yaws is classified as primary, secondary, and tertiary; this is useful, but people often have a mix of stages.[2]

Within 9–90 days (but usually about 21 days[2]) of infection, a painless but distinctive "mother yaw" nodule appears.[2] Initially reddened and inflamed,[12] it may become a papilloma, which can then become an ulcer,[7] possibly with a yellow crust.[13] Mother yaws are most commonly found on the legs and ankles, and are rarely found on the genitals (unlike syphilis)[2] The mother yaw enlarges and becomes warty in appearance. Nearby "daughter yaws" may also appear simultaneously. This primary stage resolves completely, with scarring, within 3–6 months.[12] The scar is often pigmented.[2]

Papilloma mother yaw

Papilloma mother yaw.jpg.webp) Mother yaw nodule with central ulceration and a yellow crust

Mother yaw nodule with central ulceration and a yellow crust Ulcerated mother yaw

Ulcerated mother yaw Ulcerated mother yaw

Ulcerated mother yaw Healed primary yaw lesion, showing pigmented scar

Healed primary yaw lesion, showing pigmented scar

The secondary stage occurs months to two years later (but usually 1–2 months later), and may thus begin when the mother yaw has not yet healed.[2] It happens when the bacterium spreads in the blood and lymph. It begins as multiple, pinhead-like papules; these initial lesions grow and change in appearance and may last weeks before healing, with or without scarring.[2]

Secondary yaws typically shows widespread skin lesions that vary in appearance, including "crab yaws" (areas of skin of abnormal colour) on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet[12] (named for the crab-like gait they cause people with painful soles to assume[2]). These may show desquamation. These secondary lesions frequently ulcerate and are then highly infectious, but heal after 6 months or more.

Secondary yaws affects the skin and bones.[12] The most common bone-related problem is periostitis, an inflammation around the bone, often occurs in the bones of the fingers and the long bones of the lower arms and legs, causing swollen fingers and limbs.[12] This causes pain at night and thickening of the affected bones (periostitis).[2] About 75% of infected children surveyed in Papua New Guinea reported joint pain.[2] Swollen lymph nodes, fever, and malaise are also common.[12]

After primary and secondary yaws (and possibly, in some cases, without these phases), a latent infection develops.[2] Within five years (rarely, within ten years[2]) it can relapse and become active again, causing further secondary lesions, which may infect others.[12] These relapse lesions are most commonly found around the armpits, mouth, and anus.[2]

Secondary yaws begin as multiple small lesions.

Secondary yaws begin as multiple small lesions. The small lesions grow.

The small lesions grow. Secondary lesions vary in appearance (see list of terms)

Secondary lesions vary in appearance (see list of terms).jpg.webp) Here two different appearances (papulosquamous plaque and yellow-crusted nodules) are seen in the same 10-year-old person (large-scale of both, close-up of nodules)

Here two different appearances (papulosquamous plaque and yellow-crusted nodules) are seen in the same 10-year-old person (large-scale of both, close-up of nodules) Hypopigmentation and an crusted erosion, elbow of a 5-year-old

Hypopigmentation and an crusted erosion, elbow of a 5-year-old Secondary yaws; hypopigmented areas of skin topped with pink and brown papules, 9-year-old

Secondary yaws; hypopigmented areas of skin topped with pink and brown papules, 9-year-old Erosion on the sole of the foot, close-up (large-scale). If deeper, it would be an ulcer

Erosion on the sole of the foot, close-up (large-scale). If deeper, it would be an ulcer Secondary yaws papilloma (same 9-year-old as pictures of feet)

Secondary yaws papilloma (same 9-year-old as pictures of feet) Secondary breakout in a Javanese child age of 12 years. Wax model

Secondary breakout in a Javanese child age of 12 years. Wax model.jpg.webp) Secondary yaws scars in an adult with childhood history of yaws

Secondary yaws scars in an adult with childhood history of yaws

An estimated 10% of people with yaws formerly were thought to develop tertiary disease symptoms, but more recently, tertiary yaws has been less frequently reported.[12][2]

Tertiary yaws can include gummatous nodules. It most commonly affects the skin. The skin of the palms and soles may thicken (hyperkeratosis). Nodules ulcerating near joints can cause tissue death. Periostitis can be much more severe. The shinbones may become bowed (saber shin)[12] from chronic periostitis.[2]

Yaws may or may not have cardiovascular or neurological effects; definitive evidence is lacking.[2]

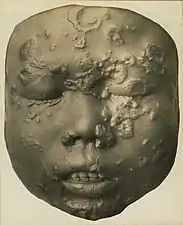

Rhinopharyngitis mutilans

Rhinopharyngitis mutilans,[14][15] also known as gangosa, is a destructive ulcerative condition that usually originates about the soft palate and spreads into the hard palate, nasopharynx, and nose, resulting in mutilating cicatrices, and outward to the face, eroding intervening bone, cartilage, and soft tissues. It occurs in late stages of yaws, usually 5 to 10 years after first symptoms of infection. This is now rare.[2] Very rarely,[2] yaws may cause bone spurs in the upper jaw near the nose (gondou); gondou was rare even when yaws was a common disease.[12]

_(14761746096).jpg.webp) Deep ulceration occurs in tertiary yaws

Deep ulceration occurs in tertiary yaws_(14804596673).jpg.webp) Severe tertiary yaws; gangosa

Severe tertiary yaws; gangosa_p1117_(cropped_to_goundu).jpg.webp) Goundu, a very rare yaws-caused deformity around the nose

Goundu, a very rare yaws-caused deformity around the nose

Cause

The disease is transmitted by skin-to-skin contact with an infective lesion,[12] with the bacterium entering through a pre-existing cut, bite, or scratch.[2]

Early (primary and secondary) yaws lesions have a higher bacterial load, thus are more infectious.[2] Both papillomas and ulcers are infectious.[7] Infectivity is thought to last 12–18 months after infection, longer if a relapse occurs. Early yaws lesions are often itchy, and more lesions may form along lines that are scratched. Yaws may be evolving less conspicuous lesions.[2]

Yaws is most common among children, who spread it by playing together.[6] It is not thought to be transmitted from mother to child in the womb.[6][2] Yaws is not a venereal disease.[2]

T. pallidum pertenue has been identified in nonhuman primates (baboons, chimpanzees, and gorillas) and experimental inoculation of human beings with a simian isolate causes yaws-like disease. However, no evidence exists of cross-transmission between human beings and primates, but more research is needed to discount the possibility of a yaws animal reservoir in nonhuman primates.[6]

Diagnosis

Most often the diagnosis is made clinically.[16] Dark field microscopy of samples taken from early lesions (particularly ulcerative lesions[16]) may show the responsible bacteria; the spirochaetes are only 0.3 µm wide by 6–20 µm long, so light-field microscopy does not suffice.[2]

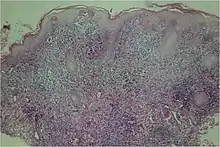

A microscopic examination of a biopsy of a yaw may show skin with clear epidermal hyperplasia (a type of skin thickening) and papillomatosis (a type of surface irregularity), often with focal spongiosis (an accumulation of fluid in specific part of the epidermis). Immune system cells, neutrophils and plasma cells, accumulate in the skin, in densities that may cause microabscesses.

Warthin–Starry or Levaditi silver stains selectively stain T. pallidum, and direct and indirect immunofluorescence and immunoperoxidase tests can detect polyclonal antibodies to T. pallidums. Histology often shows some spatial features which distinguish yaws from syphilis (syphilis is more likely to be found in the dermis, not the epidermis, and shows more endothelial cell proliferation and vascular obliteration).[2]

Blood-serum (serological) tests are increasingly done at the point of care. They include a growing range of treponemal and nontreponemal assays. Treponemal tests are more specific, and are positive for any one who has ever been infected with yaws; they include the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay. Nontreponemal assays can be used to indicate the progress of an infection and a cure, and positive results weaken and may become negative after recovery, especially after a case treated early.[12] They include the venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL; requires microscopy) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR; naked-eye result) tests, both of which flocculate patient-derived antibodies with antigens.[2]

Serological tests cannot distinguish yaws from the closely related syphilis;[2] no test distinguishing yaws from syphilis is widely available. The two genomes differ by about 0.2%. PCR and DNA sequencing can distinguish the two.[2] There are also no common blood tests which distinguish among the four treponematoses: syphilis (Treponema pallidum pallidum), yaws (Treponema pallidum pertenue), bejel (Treponema pallidum endemicum), and pinta (Treponema carateum).[16]

Haemophilus ducreyi infections can cause skin conditions that mimic primary yaws. People infected with Haemophilus ducreyi lesions may or may not also have latent yaws, and thus may or may not test positive on serological tests. This was discovered in the mid-2010s.[12] It seems that a recently diverged strain of Haemophilus ducreyi has evolved from being a sexually transmitted infection to being a skin ulcer pathogen that looks like yaws.[17]

Yaws has been reported in nonendemic countries.[2]

Treatment

Treatment is normally by a single intramuscular injection of long-acting benzathine benzylpenicillin, or less commonly by a course of other antibiotics, such as azithromycin or tetracycline tablets. Penicillin has been the front-line treatment since at least the 1960s, but there is no solid evidence of the evolution of penicillin resistance in yaws.[12]

The historical strategy for the eradication of yaws (1952–1964) was:[12]

| Prevalence of clinically active yaws | Treatment strategy |

|---|---|

| Hyperendemic: above 10% | Benzathine benzylpenicillin to the whole community

(total mass treatment) |

| Mesoendemic: 5–10% | Treat all active cases, all children under 15 and all contacts of infectious cases

(juvenile mass treatment) |

| Hypoendemic: under 5% | Treat all active cases and all household and other contacts

(selective mass treatment) |

Benzathine benzylpenicillin requires a cold chain and staff who can inject it, and there is a small risk of anaphylaxis. It was also not reliably available during the 2010s; there have been supply shortages.[12]

In the 2010s, a single oral dose of azithromycin was shown to be as effective as intramuscular penicillin.[18][12] Unlike penicillin, there is strong evidence that yaws is evolving antibiotic resistance to azithromycin; there are two known mutations in the bacterium, each of which can cause resistance and make the treatment ineffective. This has threatened eradication efforts.[12]

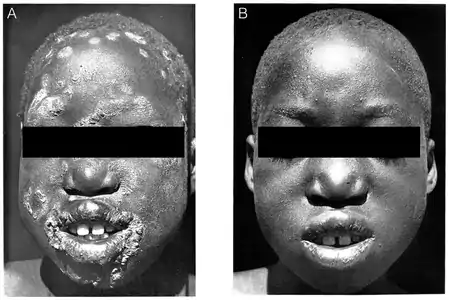

Within 8–10 hours of penicillin treatment, bacteria can no longer be found in lesion biopsies.[2] Primary and secondary lesions usually heal in 2–4 weeks; bone pain may improve within two days.[12] If treated early enough, bone deformities may reverse and heal.[2] Primary and secondary stage lesions may heal completely, but the destructive changes of tertiary yaws are largely irreversible.

If lesions do not heal, or RPR test results do not improve, this may indicate treatment failure or re-infection; the treatment is typically repeated.[2] WHO guidelines says that any presumed treatment failures at 4 weeks require macrolide resistance testing.[7]

Secondary yaws in the left armpit of a ten-year-old, 2020

Secondary yaws in the left armpit of a ten-year-old, 2020 Same person, 2 weeks and 3.5 months after a single-dose azithromycin

Same person, 2 weeks and 3.5 months after a single-dose azithromycin Before and two weeks after a single injection of benzathine penicillin, 1950s.

Before and two weeks after a single injection of benzathine penicillin, 1950s.

Epidemiology

Where the road ends, yaws begins

—WHO saying, quoted by Kingsley Asiedu.[20]

Because T. pallidum pertenue is temperature- and humidity-dependent, yaws is found in humid tropical[12] forest regions in South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania.[9][7]

About three quarters of people affected are children under 15 years of age, with the greatest incidence in children 6–10 years old.[21] Therefore, children are the main reservoir of infection.[9]

It is more common in remote areas, where access to treatment is poorer.[12] It is associated with poverty and poor sanitation facilities and personal hygiene.[9][22][7]

Worldwide, almost 85% of yaws cases are in Ghana, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. Rates in sub-Saharan Africa are low, but tend to be concentrated in specific populations. As of 2015, it is estimated that about 89 million people live in yaws-endemic areas, but data are poor, and this is likely an over-estimate.[22]

In the early 1900s, yaws was very common; in sub-saharan Africa, it was more frequently treated than malaria, sometimes making up more than half of treatments.[9]

Mass treatment campaigns in the 1950s reduced the worldwide prevalence from 50 to 150 million to fewer than 2.5 million; however, during the 1970s there were outbreaks in South-East Asia, and there have been continued sporadic cases in South America. As of 2011, it was unclear how many people worldwide were currently infected.[23]

From 2008 to 2012, 13 countries reported over 300,000 new cases to the WHO. There was no system for certifying local elimination of yaws, and it is not known whether the lack of reports from some countries is because they stopped having yaws cases or because they stopped reporting them. It is estimated that if there is not an active surveillance programme, there is less than a 1-in-2 chance that a country will successfully report yaws cases (if it gets them) in over three-quarters of countries with a history of yaws. These countries are thought to need international assistance to mount effective surveillance.[24]

Generally, yaws is not a notifiable disease.[22]

History

Examination of remains of Homo erectus from Kenya, that are about 1.6 million years old, has revealed signs typical of yaws. The genetic analysis of the yaws causative bacteria—Treponema pallidum pertenue—has led to the conclusion that yaws is the most ancient of the four known Treponema diseases. All other Treponema pallidum subspecies probably evolved from Treponema pallidum pertenue. Yaws is believed to have originated in tropical areas of Africa, and spread to other tropical areas of the world via immigration and the slave trade. The latter is likely the way it was introduced to Europe from Africa in the 15th century. The first unambiguous description of yaws was made by the Dutch physician Willem Piso. Yaws was clearly described in 1679 among African slaves by Thomas Sydenham in his epistle on venereal diseases, although he thought that it was the same disease as syphilis. The causative agent of yaws was discovered in 1905 by Aldo Castellani in ulcers of patients from Ceylon.[6]

The current English name is believed to be of Carib origin, from "yaya", meaning sore.[16]

Towards the end of the Second World War yaws became widespread in the North of Malaya under Japanese occupation. After the country was liberated, the population was treated for yaws by injections of arsenic, of which there was a great shortage, so only those with stage 1 were treated.[25]

Eradication

A series of WHO yaws control efforts, which began shortly after creation of the WHO in 1948, succeeded in eradicating the disease locally from many countries, but have not lasted long enough to eradicate it globally. The Global Control of Treponematoses (TCP) programme by the WHO and the UNICEF launched in 1952 and continued until 1964. A 1953 questionnaire-based estimate was that there were 50–150 million yaws cases in 90 countries.[22] The global prevalence of yaws and the other endemic treponematoses, bejel and pinta, was reduced by the Global Control of Treponematoses (TCP) programme between 1952 and 1964 from about 50 million cases to about 2.5 million (a 95% reduction).[26] However, "premature integration of yaws and other endemic treponematoses activities into weak primary health-care systems, and the dismantling of the vertical eradication programmes after 1964, led to the failure to finish with the remaining 5% of cases"[26] and led to a resurgence of yaws in the 1970s, with the largest number of case found in the Western Africa region.[23][27] Following the cessation of this program, resources, attention and commitment for yaws gradually disappeared and yaws remained at a low prevalence in parts of Asia, Africa, and the Americas with sporadic outbreaks. With few cases, mainly affecting poor, remote communities with little access to treatment, yaws became poorly known, yaws knowledge and skills died out even among health professionals, and yaws eradication was not seen as a high priority. Although a single injection of long-acting penicillin or other beta lactam antibiotic cures the disease and is widely available and the disease highly localised, many eradication campaigns ended in complacency and neglect; even in areas where transmission was successfully interrupted, re-introduction from infected areas occurred. Yaws eradication remained a priority in south-east Asia.[20][28] In 1995, the WHO estimated 460,000 worldwide cases.[29]

In the Philippines, yaws stopped being listed as a notifiable disease in 1973; as of 2020, it is still present in the country.[3]

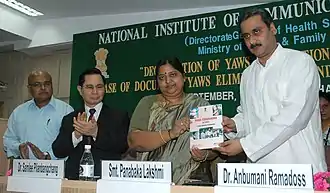

India implemented a successful Yaws eradication campaign that resulted in the 2016 certification by the WHO that India was free of yaws.[30][28][31] In 1996 there were 3,571 yaws cases in India; in 1997 after a serious elimination effort began the number of cases fell to 735. By 2003 the number of cases was 46. The last clinical case in India was reported in 2003 and the last latent case in 2006;[32] certification by the WHO was achieved in 2016.[30][33]

In 2012 the WHO officially targeted yaws for eradication by 2020 following the development of orally administered azithromycin as a treatment, but missed that target.[34][35][36] The Morges approach (named after Morges, Switzerland, where a meeting on it was held[37]) involved mass treatment with azithromycin. This was safe, but ran into problems with antibiotic resistance, and did not fully interrupt transmission.[12]

The discovery that oral antibiotic azithromycin can be used instead of the previous standard, injected penicillin, was tested on Lihir Island from 2013 to 2014;[38] a single oral dose of the macrolide antibiotic reduced disease prevalence from 2.4% to 0.3% at 12 months.[39] The WHO now recommends both treatment courses (oral azithromycin and injected penicillin), with oral azithromycin being the preferred treatment.[40]

As of 2020, there were 15 countries known to be endemic for yaws, with the recent discovery of endemic transmission in Liberia and the Philippines.[41] In 2020, 82 564 cases of yaws were reported to the WHO and 153 cases were confirmed. The majority of the cases are reported from Papua New Guinea and with over 80% of all cases coming from one of three countries in the 2010–2013 period: Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Ghana.[41][42] A WHO meeting report in 2018 estimated the total cost of elimination to be US$175 million (excluding Indonesia).[43]

In the South-East Asian Regional Office of the WHO, regional eradication efforts are focused on the remaining endemic countries in this region (Indonesia and East Timor)[44][45] after India was declared free of yaws in 2016.[46][43]

Although yaws is highly localized and eradication may be feasible, humans may not be the only reservoir of infection.[23]

References

- Maxfield, L; Crane, JS (January 2020). "Yaws (Frambesia tropica, Thymosis, Polypapilloma tropicum, Parangi, Bouba, Frambosie, Pian)". Stat Pearls. PMID 30252269.

- Marks, M; Lebari, D; Solomon, AW; Higgins, SP (September 2015). "Yaws". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 26 (10): 696–703. doi:10.1177/0956462414549036. PMC 4655361. PMID 25193248.

- Dofitas, BL; Kalim, SP; Toledo, CB; Richardus, JH (30 January 2020). "Yaws in the Philippines: first reported cases since the 1970s". Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40249-019-0617-6. PMC 6990502. PMID 31996251.

- Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- James WD, Berger TG, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0. OCLC 62736861.

- Mitjà O; Asiedu K; Mabey D (2013). "Yaws". The Lancet. 381 (9868): 763–73. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62130-8. PMID 23415015. S2CID 208791874.

- "Yaws Fact sheet N°316". World Health Organization. February 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Mitjà O; Hays R; Rinaldi AC; McDermott R; Bassat Q (2012). "New treatment schemes for yaws: the path toward eradication" (pdf). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 55 (3): 406–412. doi:10.1093/cid/cis444. PMID 22610931. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014.

- Asiedu, Kingsley; Fitzpatrick, Christopher; Jannin, Jean (25 September 2014). "Eradication of Yaws: Historical Efforts and Achieving WHO's 2020 Target". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (9): 696–703. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003016. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 4177727. PMID 25193248.

- Mitjà, O; Marks, M; Konan, DJ; Ayelo, G; Gonzalez-Beiras, C; Boua, B; Houinei, W; Kobara, Y; Tabah, EN; Nsiire, A; Obvala, D; Taleo, F; Djupuri, R; Zaixing, Z; Utzinger, J; Vestergaard, LS; Bassat, Q; Asiedu, K (June 2015). "Global epidemiology of yaws: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 3 (6): e324-31. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00011-X. PMC 4696519. PMID 26001576.

- "Number of cases of yaws reported". World Health Organization Global Health Observatory. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Marks, Michael (29 August 2018). "Advances in the Treatment of Yaws". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 3 (3): 92. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed3030092. ISSN 2414-6366. PMC 6161241. PMID 30274488.

- Yotsu, Rie R. (14 November 2018). "Integrated Management of Skin NTDs—Lessons Learned from Existing Practice and Field Research". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 3 (4): 120. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed3040120. ISSN 2414-6366. PMC 6306929. PMID 30441754.

- L. H., Bittner (1926). "Some observations on the tertiary lesions of framboesia tropica, or yaws". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1 (2): 123–130. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1926.s1-6.123.

- Berger, Stephen (1 February 2015). Infectious Diseases of Nauru. GIDEON Informatics Inc. p. 320. ISBN 9781498805742. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- Davis CP, Stoppler MC. "Yaws". MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- Lewis, David A.; Mitjà, Oriol (February 2016). "Haemophilus ducreyi: from sexually transmitted infection to skin ulcer pathogen". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 29 (1): 52–57. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000226. ISSN 1473-6527. PMID 26658654. S2CID 1699547.

- Mitjà, O; Hays, R; Ipai, A; Penias, M; Paru, R; Fagaho, D; de Lazzari, E; Bassat, Q (28 January 2012). "Single-dose azithromycin versus benzathine benzylpenicillin for treatment of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial". The Lancet. 379 (9813): 342–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61624-3. PMID 22240407. S2CID 17517869.

- "Yaws status of endemicity and number of cases". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Asiedu, Kingsley (July 2008). "The return of yaws". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (7): 507–8. doi:10.2471/blt.08.040708. PMC 2647480. PMID 18670660.

- "Yaws". WHO Fact sheet. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- Mitjà, Oriol; Marks, Michael; Konan, Diby J P; Ayelo, Gilbert; Gonzalez-Beiras, Camila; Boua, Bernard; Houinei, Wendy; Kobara, Yiragnima; Tabah, Earnest N; Nsiire, Agana; Obvala, Damas; Taleo, Fasiah; Djupuri, Rita; Zaixing, Zhang; Utzinger, Jürg; Vestergaard, Lasse S; Bassat, Quique; Asiedu, Kingsley (19 May 2015). "Global epidemiology of yaws: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 3 (6): e324–e331. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00011-X. ISSN 2214-109X. PMC 4696519. PMID 26001576.

- Capuano, C; Ozaki, M (2011). "Yaws in the Western Pacific Region: A Review of the Literature". Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011: 642832. doi:10.1155/2011/642832. PMC 3253475. PMID 22235208.

- Fitzpatrick, Christopher; Asiedu, Kingsley; Solomon, Anthony W.; Mitja, Oriol; Marks, Michael; Van der Stuyft, Patrick; Meheus, Filip (4 December 2018). "Prioritizing surveillance activities for certification of yaws eradication based on a review and model of historical case reporting". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 12 (12): e0006953. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006953. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 6294396. PMID 30513075.

- "All things uncertain: The story of the G.I.S." by Phyllis Stewart Brown

- "WHO renews efforts to achieve global eradication of yaws by 2020".

- Rinaldi A (2008). "Yaws: a second (and maybe last?) chance for eradication". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (8): e275. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000275. PMC 2565700. PMID 18846236.

- Asiedu K; Amouzou, B; Dhariwal, A; Karam, M; Lobo, D; Patnaik, S; Meheus, A (2008). "Yaws eradication: past efforts and future perspectives". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (7): 499–500. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.055608. PMC 2647478. PMID 18670655. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- "Integrating neglected tropical diseases in global health and development". Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Friedrich, M. J. (20 September 2016). "WHO Declares India Free of Yaws and Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus". JAMA. 316 (11): 1141. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12649. ISSN 1538-3598. PMID 27654592.

- WHO South-East Asia report of an intercountry workshop on Yaws eradication, 2006 Archived 8 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Akbar, S (7 August 2011). "Another milestone for India: Yaws eradication". The Asian Age. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Yaws Eradication Programme (YEP)". NCDC, Dte. General of Health Services, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Eradication of yaws – the Morges Strategy" (pdf). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 87 (20). 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Maurice, J (2012). "WHO plans new yaws eradication campaign". The Lancet. 379 (9824): 1377–78. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60581-9. PMID 22509526. S2CID 45958274. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

- Rinaldi A (2012). "Yaws eradication: facing old problems, raising new hopes". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (11): e18372. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001837. PMC 3510082. PMID 23209846.

- "Summary report of a consultation on the eradication of yaws". WHO. WHO. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017.

- Drug and a syphilis test offer hope of yaws eradication Archived 13 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Thomas Reuter Foundation, accessed 10 May 2013

- Mitjà O, Houinei W, Moses P, Kapa A, Paru R, Hays R, Lukehart S, Godornes C, Bieb SV, Grice T, Siba P, Mabey D, Sanz S, Alonso PL, Asiedu K, Bassat Q (February 2015). "Mass treatment with single-dose azithromycin for yaws". The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (8): 703–10. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1408586. hdl:2445/68722. PMID 25693010. S2CID 5762563.

- "Yaws". www.who.int.

- "Yaws".

- Mitjà, Oriol; Marks, Michael; Konan, Diby J P; Ayelo, Gilbert; Gonzalez-Beiras, Camila; Boua, Bernard; Houinei, Wendy; Kobara, Yiragnima; Tabah, Earnest N; Nsiire, Agana; Obvala, Damas; Taleo, Fasiah; Djupuri, Rita; Zaixing, Zhang; Utzinger, Jürg; Vestergaard, Lasse S; Bassat, Quique; Asiedu, Kingsley (19 May 2015). "Global epidemiology of yaws: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 3 (6): e324–e331. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00011-X. PMC 4696519. PMID 26001576.

- Report of a global meeting on yaws eradication surveillance, monitoring and evaluation: Geneva, 29–30 January 2018. World Health Organization. 2018. hdl:10665/276314.

- Asiedu, Kingsley; Amouzou, Bernard; Dhariwal, Akshay; Karam, Marc; Lobo, Derek; Patnaik, Sarat; Meheus, André (July 2008). "Yaws eradication: past efforts and future perspectives". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (7): 499–499A. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.055608. PMC 2647478. PMID 18670655.

- Regional strategic plan for elimination of yaws from South-East Asia Region 2012-2020. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2013. hdl:10665/205830.

- Friedrich, M.J. (20 September 2016). "WHO Declares India Free of Yaws and Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus". JAMA. 316 (11): 1141. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12649. PMID 27654592.

External links

- "Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 168.