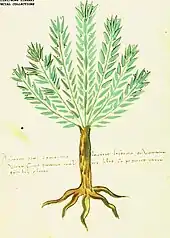

Rosemary

Salvia rosmarinus, commonly known as rosemary, is a shrub with fragrant, evergreen, needle-like leaves and white, pink, purple, or blue flowers, native to the Mediterranean region.[3] Until 2017, it was known by the scientific name Rosmarinus officinalis, now a synonym.[4]

| Rosemary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Genus: | Salvia |

| Species: | S. rosmarinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Salvia rosmarinus | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

It is a member of the sage family Lamiaceae, which includes many other medicinal and culinary herbs. The name "rosemary" derives from Latin ros marinus ("dew of the sea").[5][6] Rosemary has a fibrous root system.[3]

Description

Rosemary is an aromatic evergreen shrub with leaves similar to hemlock needles. It is native to the Mediterranean and Asia, but is reasonably hardy in cool climates. Special cultivars like 'Arp' can withstand winter temperatures down to about −20 °C.[7] It can withstand droughts, surviving a severe lack of water for lengthy periods.[8] In some parts of the world, it is considered a potentially invasive species.[3] The seeds are often difficult to start, with a low germination rate and relatively slow growth, but the plant can live as long as 30 years.[3]

Forms range from upright to trailing; the upright forms can reach 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) tall, rarely 2 m (6 ft 7 in). The leaves are evergreen, 2–4 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄2 in) long and 2–5 mm broad, green above, and white below, with dense, short, woolly hair.

The plant flowers in spring and summer in temperate climates, but the plants can be in constant bloom in warm climates; flowers are white, pink, purple or deep blue.[3] Rosemary also has a tendency to flower outside its normal flowering season; it has been known to flower as late as early December, and as early as mid-February (in the northern hemisphere).[9]

Taxonomy

Salvia rosmarinus is now considered one of many hundreds of species in the genus Salvia.[2] Formerly it was placed in a much smaller genus, Rosmarinus, which contained only two to four species including R. officinalis,[10] which is now considered a synonym of S. rosmarinus. The other species most often recognized is the closely related, Salvia jordanii (formerly Rosmarinus eriocalyx), of the Maghreb of Africa and Iberia.

Both the original and current genus names of the species were applied by the 18th-century naturalist and founding taxonomist Carl Linnaeus. Elizabeth Kent noted in her Flora Domestica (1823), "The botanical name of this plant is compounded of two Latin words, signifying Sea-dew; and indeed Rosemary thrives best by the sea."[11]

History

The first mention of rosemary is found on cuneiform stone tablets as early as 5000 BCE.[12] After that not much is known, except that Egyptians used it in their burial rituals.[13] There is no further mention of rosemary until the ancient Greeks and Romans. Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) wrote about it in The Natural History,[14] as did Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 CE to c. 90 CE), a Greek botanist (amongst other things). He talked about rosemary in his most famous writing, De Materia Medica, one of the most influential herbal books in history.[15]

The herb then made its way east to China and was naturalized there as early as 220 CE,[3] during the late Han Dynasty.[16]

Rosemary came to England at an unknown date; the Romans probably brought it when they invaded in the first century, but there are no viable records about rosemary arriving in Britain until the 8th century CE. This was credited to Charlemagne, who promoted herbs in general, and ordered rosemary to be grown in monastic gardens and farms.[17]

There are also no records of rosemary being properly naturalized in Britain until 1338, when cuttings were sent to Queen Philippa by her mother, Countess Joan of Hainault. It included a letter that described the virtues of rosemary and other herbs that accompanied the gift. The original manuscript can be found in the British Museum. The gift was then planted in the garden of the old palace of Westminster. After this, rosemary is found in most English herbal texts, and is widely used for medicinal and culinary purposes.[18] Hungary water, which dates to the 14th century, was one of the first alcohol-based perfumes in Europe, and was primarily made from distilled rosemary.[19]

Rosemary finally arrived in the Americas with early European settlers in the beginning of the 17th century. It soon was spread to South America and global distribution.[3]

Usage

Upon cultivation, the leaves, twigs, and flowering apices are extracted for use.[20] Rosemary is used as a decorative plant in gardens. The leaves are used to flavor various foods, such as stuffing and roast meats.[21]

Cultivation

Since it is attractive and drought-tolerant, rosemary is used as an ornamental plant in gardens and for xeriscape landscaping, especially in regions of Mediterranean climate.[3] It is considered easy to grow and pest-resistant. Rosemary can grow quite large and retain attractiveness for many years, can be pruned into formal shapes and low hedges, and has been used for topiary. It is easily grown in pots. The groundcover cultivars spread widely, with a dense and durable texture.[3]

Rosemary grows on loam soil with good drainage in an open, sunny position. It will not withstand waterlogging and some varieties are susceptible to frost. It grows best in neutral to alkaline conditions (pH 7–7.8) with average fertility. It can be propagated from an existing plant by clipping a shoot (from a soft new growth) 10–15 cm (4–6 in) long, stripping a few leaves from the bottom, and planting it directly into soil.

Cultivars

Numerous cultivars have been selected for garden use.

- 'Albus' – white flowers

- 'Arp' – leaves light green, lemon-scented and especially cold-hardy

- 'Aureus' – leaves speckled yellow

- 'Benenden Blue' – leaves narrow, dark green

- 'Blue Boy' – dwarf, small leaves

- 'Blue Rain' – pink flowers

- 'Golden Rain' – leaves green, with yellow streaks

- 'Gold Dust' – dark green leaves, with golden streaks but stronger than 'Golden Rain'

- 'Haifa' – low and small, white flowers

- 'Irene' – low and lax, trailing, intense blue flowers

- 'Lockwood de Forest' – procumbent selection from 'Tuscan Blue'

- 'Ken Taylor' – shrubby

- 'Majorica Pink' – pink flowers

- 'Miss Jessopp's Upright' – distinctive tall fastigiate form, with wider leaves.

- 'Pinkie' – pink flowers

- 'Prostratus' – lower groundcover

- 'Pyramidalis' (or 'Erectus') – fastigate form, pale blue flowers

- 'Remembrance' (or 'Gallipoli') – taken from the Gallipoli Peninsula[22]

- 'Roseus' – pink flowers

- 'Salem' – pale blue flowers, cold-hardy similar to 'Arp'

- 'Severn Sea' – spreading, low-growing, with arching branches, flowers deep violet

- 'Sudbury Blue' – blue flowers

- 'Tuscan Blue' – traditional robust upright form

- 'Wilma's Gold' – yellow leaves

The following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:[23]

Culinary use

.JPG.webp)

Rosemary leaves are used as a flavoring in foods,[3] such as stuffing and roast lamb, pork, chicken, and turkey. Fresh or dried leaves are used in traditional Mediterranean cuisine. They have a bitter, astringent taste and a characteristic aroma which complements many cooked foods. Herbal tea can be made from the leaves. When roasted with meats or vegetables, the leaves impart a mustard-like aroma with an additional fragrance of charred wood that goes well with barbecued foods.

In amounts typically used to flavor foods, such as one teaspoon (1 gram), rosemary provides no nutritional value.[28][29] Rosemary extract has been shown to improve the shelf life and heat stability of omega 3-rich oils which are prone to rancidity.[30] Rosemary is also an effective antimicrobial herb.[31]

Fragrance

Rosemary oil is used for purposes of fragrant bodily perfumes or to emit an aroma into a room. It is also burnt as incense, and used in shampoos and cleaning products.

Phytochemicals

Rosemary contains a number of phytochemicals, including rosmarinic acid, camphor, caffeic acid, ursolic acid, betulinic acid, carnosic acid, and carnosol.[32] Rosemary essential oil contains 10–20% camphor.[33]

Folklore and customs

The plant or its oil have been used in folk medicine in the belief it may have medicinal effects. Rosemary was considered sacred to ancient Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks.[20] In Don Quixote (Part One, Chapter XVII), the fictional hero uses rosemary in his recipe for balm of fierabras.[34]

The plant has been used as a symbol for remembrance during war commemorations and funerals in Europe and Australia.[35] Mourners would throw it into graves as a symbol of remembrance for the dead. In Australia, sprigs of rosemary are worn on ANZAC Day and sometimes Remembrance Day to signify remembrance; the herb grows wild on the Gallipoli Peninsula, where many Australians died during World War I.[35]

Several Shakespeare plays refer to the use of rosemary in burial or memorial rites. In Shakespeare's Hamlet, Ophelia says, "There's rosemary, that's for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember."[36] It likewise appears in Shakespeare's Winter's Tale in Act 4 Scene 4, where Perdita talks about "Rosemary and Rue".[37] In Act 4 Scene 5 of Romeo and Juliet, Friar Lawrence admonishes the Capulet household to "stick your rosemary on this fair corse, and as the custom is, and in her best array, bear her to church."

In the Spanish fairy tale The Sprig of Rosemary, the heroine touches the hero with the title rosemary in order to restore his magically lost memory.[38]

See also

- Four thieves vinegar

- Scented water

References

- "Salvia rosmarinus Spenn". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- Drew, Bryan T.; González-Gallegos, Jesús Guadalupe; Xiang, Chun-Lei; Kriebel, Ricardo; Drummond, Chloe P.; Walker, Jay B.; Sytsma, Kenneth J. (2017). "Salvia united: The greatest good for the greatest number". Taxon. 66 (1): 133–145. doi:10.12705/661.7. S2CID 90993808.

- "Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary)". Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- Drew; et al. (February 2017). "Salvia united: The greatest good for the greatest number".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Room, Adrian (1988). A Dictionary of True Etymologies. Taylor & Francis. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-415-03060-1.

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 66.

- Tucker, Arthur O.; Maciarello, Michael J. (September 1986). "The essential oils of some rosemary cultivars". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 1 (4–5): 137–142. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730010402.

- "How to Grow Rosemary". Garden Action. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- McCoy, Michael (27 June 2012). "The good graces of rosemary". The Gardenist. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- Rosselló, J. A.; Cosín, R.; Boscaiu, M.; Vicente, O.; Martínez, I.; Soriano, P. (2006). "Intragenomic diversity and phylogenetic systematics of wild rosemaries (Rosmarinus officinalis L. s.l., Lamiaceae) assessed by nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences (ITS)". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 262 (1–2): 1–12. doi:10.1007/s00606-006-0454-5. JSTOR i23655428. S2CID 25645455.

- Kent, Elizabeth (1823). Flora Domestica, or the Portable Flower-Garden. Taylor and Hessey. p. 330.

- Leafy Medicinal Herbs: Botany, Chemistry, Postharvest Technology and Uses by Dawn Ambrose, 216, 210-11

- Boi, Marzia. "The Ethnocultural significance for the use of plants in Ancient Funerary Rituals and its possible implications with pollens found on the Shroud of Turin" (PDF). www.shroud.com. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, trans. John Bostock (London: Taylor and Francis, 1855)

- Pedanius Dioscorides of Anazarbos (2000). Osbaldeston, Tess Anne (ed.). De materia medica: Being an herbal with many other medicinal matters. Written in Greek in the first century of the common era. Johannesburg: IBIDIS. ISBN 0-620-23435-0.

- "Han dynasty | Definition, Map, Culture, Art, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-03-19.

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs: History, Botany by Deborah Madison, 2017, p.266

- A Brief History of Thyme and other Herbs by Miranda Seymour, 2002, p.96

- Sullivan, Catherine (1994-03-01). "Searching for nineteenth-century Florida water bottles". Historical Archaeology. 28 (1): 78–98. doi:10.1007/BF03374182. ISSN 0440-9213. S2CID 162639733.

- Burlando, Bruno; Verotta, Luisella; Cornara, Laura; Bottini-Massa, Elisa (2010). Herbal Principles in Cosmetics Properties and Mechanisms of Action. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4398-1214-3.

- "About the Herb Rosemary and Uses". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- Rosemary. Gardenclinic.com.au. Retrieved on 2014-06-03.

- "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 93. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Rosmarinus officinalis (Angustifolia Group) 'Benenden Blue'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Rosmarinus officinalis 'Miss Jessopp's Upright'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Rosmarinus officinalis 'Severn Sea'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Rosmarinus officinalis 'Sissinghurst Blue'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Nutrition Facts – Dried rosemary, one teaspoon (1 g)". nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast, USDA Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014.

- "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference". NAL.usda.gov. US Department of Agriculture. 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Daniells, Stephen (20 November 2017). "Oregano, rosemary extracts promise omega-3 preservation". Food Navigator.

- Nieto, G.; Ros, G.; Castillo, J. (2018). "Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis, L.): A Review". Medicines. 5 (3): 98. doi:10.3390/medicines5030098. PMC 6165352. PMID 30181448.

- Vallverdú-Queralt, Anna; Regueiro, Jorge; Martínez-Huélamo, Miriam; Rinaldi Alvarenga, José Fernando; Leal, Leonel Neto; Lamuela-Raventos, Rosa M. (2014). "A comprehensive study on the phenolic profile of widely used culinary herbs and spices: Rosemary, thyme, oregano, cinnamon, cumin and bay". Food Chemistry. 154: 299–307. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.12.106. PMID 24518346.

- "Rosemary | Professional". Drugs.com. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- Capuano, Thomas M. (2005). "Las huellas de otro texto médico en Don Quijote: Las virtudes del romero". Romance Notes (in Spanish). 45 (3): 303–310.

- "Rosemary". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- Shakespeare, William. Scene 13. Hamlet.

- Shakespeare, William (2005). The Winter's Tale. Simon & Schuster. p. 139.

- Lang, Andrew (1897). The Pink Fairy Book. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 237.