Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States. Founded in 1828, it was predominantly built by Martin Van Buren, who assembled a wide cadre of politicians in every state behind war hero Andrew Jackson, making it the world's oldest active political party.[11][12][13] Its main political rival has been the Republican Party since the 1850s. The party is known as a big tent,[14] and is traditionally less ideologically uniform than the Republican Party (with major individuals within it frequently holding widely differing political views) due to the broader list of unique voting blocs that compose it.[15][16][17]

Democratic Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairperson | Jaime Harrison |

| Governing body | Democratic National Committee[1][2] |

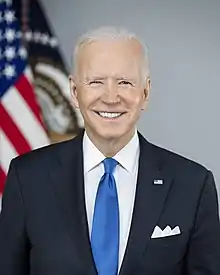

| U.S. President | Joe Biden |

| U.S. Vice President | Kamala Harris |

| Senate Majority Leader | Chuck Schumer |

| Speaker of the House | Nancy Pelosi |

| House Majority Leader | Steny Hoyer[lower-alpha 1] |

| Founders | |

| Founded | January 8, 1828[3] Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Preceded by | Democratic-Republican Party |

| Headquarters | 430 South Capitol St. SE, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Student wing |

|

| Youth wing | Young Democrats of America |

| Women's wing | National Federation of Democratic Women |

| Overseas wing | Democrats Abroad |

| Membership (2022) | |

| Ideology |

|

| Colors | Blue |

| Seats in the Senate | 48 / 100[lower-alpha 3] |

| Seats in the House of Representatives | 220 / 435 |

| State governorships | 22 / 50 |

| Seats in state upper chambers | 861 / 1,972 |

| Seats in state lower chambers | 2,432 / 5,411 |

| Territorial governorships | 3 / 5 |

| Seats in territorial upper chambers | 31 / 97 |

| Seats in territorial lower chambers | 8 / 91 |

| Website | |

| democrats | |

| |

The historical predecessor of the Democratic Party is considered to be the Democratic-Republican Party.[18][19] Before 1860, the Democratic Party supported expansive presidential power,[20] the interests of slave states,[21] agrarianism,[22] and expansionism,[22] while opposing a national bank and high tariffs.[22] It split in 1860 over slavery and won the presidency only twice[lower-alpha 4] between 1860 and 1910. In the late 19th century, it continued to oppose high tariffs and had fierce internal debates on the gold standard. In the early 20th century, it supported progressive reforms and opposed imperialism, with Woodrow Wilson winning the White House in 1912 and 1916. Since Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal coalition after 1932, the Democratic Party has promoted a social liberal platform, including Social Security and unemployment insurance.[23][5][24] The New Deal attracted strong support for the party from recent European immigrants, but caused a decline of the party's conservative pro-business wing.[25][26][27] Following the Great Society era of progressive legislation under Lyndon B. Johnson, including Medicare,[28] the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the core bases of the parties shifted, with the Southern states becoming more reliably Republican and the Northeastern states becoming more reliably Democratic.[29] As the American electorate shifted in a more conservative direction following Republican Ronald Reagan's presidency, the election of Bill Clinton marked a move for the party towards Third Way policies, with proponents branded as New Democrats, adopting a synthesis of neoliberal economic policies in combination with cultural liberalism.[30][31][32][33]

The Democratic Party's philosophy of modern liberalism blends notions of civil liberty and social equality with support for a mixed capitalist economy.[34] Corporate governance reform, environmental protection, support for organized labor, expansion of social programs, affordable college tuition, health care reform,[35] equal opportunity, and consumer protection form the core of the party's economic agenda.[36][37] On social issues, it advocates campaign finance reform,[38] LGBT rights,[39] criminal justice[40] and immigration reform,[41] stricter gun laws,[42] abortion rights,[43] and the legalization of marijuana.[44] Since the early 2010s, the Democratic Party has shifted significantly to the left on social, cultural, and religious issues.[45]

Individuals who live in urban areas, the affluent, college-educated, women, younger Americans, as well as most racial, religious, and sexual minorities are more likely to support the Democratic Party.[46][47][48][49][50][51] Its labor union element has become significantly smaller since the 1970s, with a narrow majority of union households continuing to prefer the party.[48][52][53] The party has lost support among members of the White working class and gained support among affluent and college-educated Whites since the 1980s; a similar trend has occurred among working class Hispanics since the 2010s.[45][46][47][48][51][54][55]

Including the incumbent, Joe Biden, 16 Democrats have served as President of the United States. As of 2022, the party holds a federal government trifecta (the presidency and majorities in both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate), as well as 22 state governorships, 17 state legislatures, and 14 state government trifectas. Three of the nine sitting U.S. Supreme Court justices were appointed by Democratic presidents. By registered members (in those states which permit or require registration by party affiliation), the Democratic Party is the largest party in the United States and the third largest in the world.[5]

History

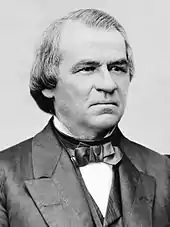

Democratic Party officials often trace its origins to the Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and other influential opponents of the conservative Federalists in 1792.[19][56] That party died out before the modern Democratic Party was organized; the Jeffersonian party also inspired the Whigs and modern Republicans. Historians argue that the modern Democratic Party was first organized in the late 1820s with the election of Andrew Jackson.[13] It was predominately built by Martin Van Buren, who assembled a wide cadre of politicians in every state behind war hero Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, making it the world's oldest active political party.[11][12][13]

Since the nomination of William Jennings Bryan in 1896, the party has generally positioned itself to the left of the Republican Party on economic issues. Democrats have been more liberal on civil rights since 1948, although conservative factions within the Democratic Party that opposed them persisted in the South until the 1960s. On foreign policy, both parties have changed positions several times.[57]

Background

The Democratic Party evolved from the Jeffersonian Republican or Democratic-Republican Party organized by Jefferson and Madison in opposition to the Federalist Party. The Democratic-Republican Party favored republicanism; a weak federal government; states' rights; agrarian interests (especially Southern planters); and strict adherence to the Constitution. The party opposed a national bank and Great Britain.[58] After the War of 1812, the Federalists virtually disappeared and the only national political party left was the Democratic-Republicans, which was prone to splinter along regional lines. The era of one-party rule in the United States, known as the Era of Good Feelings, lasted from 1816 until 1828, when Andrew Jackson became president. Jackson and Martin Van Buren worked with allies in each state to form a new Democratic Party on a national basis. In the 1830s, the Whig Party coalesced into the main rival to the Democrats.

Before 1860, the Democratic Party supported expansive presidential power,[20] the interests of slave states,[21] agrarianism,[22] and expansionism,[22] while opposing a national bank and high tariffs.[22]

19th century

The Democratic-Republican Party split over the choice of a successor to President James Monroe. The faction that supported many of the old Jeffersonian principles, led by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, became the modern Democratic Party.[59] Historian Mary Beth Norton explains the transformation in 1828:

Jacksonians believed the people's will had finally prevailed. Through a lavishly financed coalition of state parties, political leaders, and newspaper editors, a popular movement had elected the president. The Democrats became the nation's first well-organized national party ... and tight party organization became the hallmark of nineteenth-century American politics.[60]

Behind the platforms issued by state and national parties stood a widely shared political outlook that characterized the Democrats:

The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society. They viewed the central government as the enemy of individual liberty. The 1824 "corrupt bargain" had strengthened their suspicion of Washington politics. ... Jacksonians feared the concentration of economic and political power. They believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual—the artisan and the ordinary farmer—by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency, which they distrusted. Their definition of the proper role of government tended to be negative, and Jackson's political power was largely expressed in negative acts. He exercised the veto more than all previous presidents combined. Jackson and his supporters also opposed reform as a movement. Reformers eager to turn their programs into legislation called for a more active government. But Democrats tended to oppose programs like educational reform and the establishment of a public education system. They believed, for instance, that public schools restricted individual liberty by interfering with parental responsibility and undermined freedom of religion by replacing church schools. Nor did Jackson share reformers' humanitarian concerns. He had no sympathy for American Indians, initiating the removal of the Cherokees along the Trail of Tears.[61]

Opposing factions led by Henry Clay helped form the Whig Party. The Democratic Party had a small yet decisive advantage over the Whigs until the 1850s when the Whigs fell apart over the issue of slavery. In 1854, angry with the Kansas–Nebraska Act, anti-slavery Democrats left the party and joined Northern Whigs to form the Republican Party.[62][63]

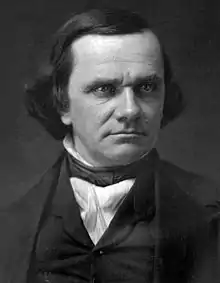

The Democrats split over slavery, with Northern and Southern tickets in the election of 1860, in which the Republican Party gained ascendancy.[64] The radical pro-slavery Fire-Eaters led walkouts at the two conventions when the delegates would not adopt a resolution supporting the extension of slavery into territories even if the voters of those territories did not want it. These Southern Democrats nominated the pro-slavery incumbent vice president, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, for president and General Joseph Lane, of Oregon, for vice president. The Northern Democrats nominated Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois for president and former Georgia Governor Herschel V. Johnson for vice president. This fracturing of the Democrats led to a Republican victory and Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States.[65]

As the American Civil War broke out, Northern Democrats were divided into War Democrats and Peace Democrats. The Confederate States of America deliberately avoided organized political parties. Most War Democrats rallied to Republican President Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans' National Union Party in the election of 1864, which featured Andrew Johnson on the Union ticket to attract fellow Democrats. Johnson replaced Lincoln in 1865, but he stayed independent of both parties.[66]

The Democrats benefited from white Southerners' resentment of Reconstruction after the war and consequent hostility to the Republican Party. After Redeemers ended Reconstruction in the 1870s and following the often extremely violent disenfranchisement of African Americans led by such white supremacist Democratic politicians as Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina in the 1880s and 1890s, the South, voting Democratic, became known as the "Solid South". Although Republicans won all but two presidential elections, the Democrats remained competitive. The party was dominated by pro-business Bourbon Democrats led by Samuel J. Tilden and Grover Cleveland, who represented mercantile, banking, and railroad interests; opposed imperialism and overseas expansion; fought for the gold standard; opposed bimetallism; and crusaded against corruption, high taxes and tariffs. Cleveland was elected to non-consecutive presidential terms in 1884 and 1892.[67]

20th century

Early 20th century

Agrarian Democrats demanding free silver, drawing on Populist ideas, overthrew the Bourbon Democrats in 1896 and nominated William Jennings Bryan for the presidency (a nomination repeated by Democrats in 1900 and 1908). Bryan waged a vigorous campaign attacking Eastern moneyed interests, but he lost to Republican William McKinley.[68]

The Democrats took control of the House in 1910, and Woodrow Wilson won election as president in 1912 (when the Republicans split) and 1916. Wilson effectively led Congress to put to rest the issues of tariffs, money, and antitrust, which had dominated politics for 40 years, with new progressive laws. He failed to secure Senate passage of the Versailles Treaty (ending the war with Germany and joining the League of Nations).[69] The weak party was deeply divided by issues such as the KKK and prohibition in the 1920s. However, it did organize new ethnic voters in Northern cities.[70]

Rise of New Deal Coalition (1930s–1960s)

The Great Depression in 1929 that began under Republican President Herbert Hoover and the Republican Congress set the stage for a more liberal government as the Democrats controlled the House of Representatives nearly uninterrupted from 1930 until 1994, the Senate for 44 of 48 years from 1930, and won most presidential elections until 1968. Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected to the presidency in 1932, came forth with federal government programs called the New Deal. New Deal liberalism meant the regulation of business (especially finance and banking) and the promotion of labor unions as well as federal spending to aid the unemployed, help distressed farmers and undertake large-scale public works projects. It marked the start of the American welfare state.[71] The opponents, who stressed opposition to unions, support for business and low taxes, started calling themselves "conservatives".[72]

Until the 1980s, the Democratic Party was a coalition of two parties divided by the Mason–Dixon line: liberal Democrats in the North and culturally conservative voters in the South, who though benefitting from many of the New Deal public works projects opposed increasing civil rights initiatives advocated by Northeastern liberals. The polarization grew stronger after Roosevelt died. Southern Democrats formed a key part of the bipartisan conservative coalition in an alliance with most of the Midwestern Republicans. The economically activist philosophy of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which has strongly influenced American liberalism, shaped much of the party's economic agenda after 1932.[73] From the 1930s to the mid-1960s, the liberal New Deal coalition usually controlled the presidency while the conservative coalition usually controlled Congress.[74]

1960s–1980s, collapse of New Deal Coalition

Issues facing parties and the United States after World War II included the Cold War and the civil rights movement. Republicans attracted conservatives and, after the 1960s, white Southerners from the Democratic coalition with their use of the Southern strategy and resistance to New Deal and Great Society liberalism. Until the 1950s, African Americans had traditionally supported the Republican Party because of its anti-slavery civil rights policies. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic.[75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82] Studies show that Southern whites, which were a core constituency in the Democratic Party, shifted to the Republican Party due to racial conservatism.[81][83][84]

The election of President John F. Kennedy from Massachusetts in 1960 partially reflected this shift. In the campaign, Kennedy attracted a new generation of younger voters. In his agenda dubbed the New Frontier, Kennedy introduced a host of social programs and public works projects, along with enhanced support of the space program, proposing a crewed spacecraft trip to the moon by the end of the decade. He pushed for civil rights initiatives and proposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but with his assassination in November 1963, he was not able to see its passage.[85]

Kennedy's successor Lyndon B. Johnson was able to persuade the largely conservative Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and with a more progressive Congress in 1965 passed much of the Great Society, including Medicare, which consisted of an array of social programs designed to help the poor, sick, and elderly. Kennedy and Johnson's advocacy of civil rights further solidified black support for the Democrats but had the effect of alienating Southern whites who would eventually gravitate toward the Republican Party, particularly after the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980. The United States' involvement in the Vietnam War in the 1960s was another divisive issue that further fractured the fault lines of the Democrats' coalition. After the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, President Johnson committed a large contingency of combat troops to Vietnam, but the escalation failed to drive the Viet Cong from South Vietnam, resulting in an increasing quagmire, which by 1968 had become the subject of widespread anti-war protests in the United States and elsewhere. With increasing casualties and nightly news reports bringing home troubling images from Vietnam, the costly military engagement became increasingly unpopular, alienating many of the kinds of young voters that the Democrats had attracted in the early 1960s. The protests that year along with assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Democratic presidential candidate Senator Robert F. Kennedy (younger brother of John F. Kennedy) climaxed in turbulence at the hotly-contested Democratic National Convention that summer in Chicago (which amongst the ensuing turmoil inside and outside of the convention hall nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey) in a series of events that proved to mark a significant turning point in the decline of the Democratic Party's broad coalition.[86]

Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon was able to capitalize on the confusion of the Democrats that year, and won the 1968 election to become the 37th president. He won re-election in a landslide in 1972 against Democratic nominee George McGovern, who like Robert F. Kennedy, reached out to the younger anti-war and counterculture voters, but unlike Kennedy, was not able to appeal to the party's more traditional white working-class constituencies. During Nixon's second term, his presidency was rocked by the Watergate scandal, which forced him to resign in 1974. He was succeeded by vice president Gerald Ford, who served a brief tenure. Watergate offered the Democrats an opportunity to recoup, and their nominee Jimmy Carter won the 1976 presidential election. With the initial support of evangelical Christian voters in the South, Carter was temporarily able to reunite the disparate factions within the party, but inflation and the Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979–1980 took their toll, resulting in a landslide victory for Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan in 1980, which shifted the political landscape in favor of the Republicans for years to come.

1990s and Third Way centrism

With the ascendancy of the Republicans under Ronald Reagan, the Democrats searched for ways to respond yet were unable to succeed by running traditional candidates, such as former vice president and Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale, who lost to Reagan in the 1984 presidential election. Many Democrats attached their hopes to the future star of Gary Hart, who had challenged Mondale in the 1984 primaries running on a theme of "New Ideas"; and in the subsequent 1988 primaries became the de facto front-runner and virtual "shoo-in" for the Democratic presidential nomination before a sex scandal ended his campaign. The party nevertheless began to seek out a younger generation of leaders, who like Hart had been inspired by the pragmatic idealism of John F. Kennedy.[87]

Arkansas governor Bill Clinton was one such figure, who was elected president in 1992 as the Democratic nominee. The Democratic Leadership Council was a campaign organization connected to Clinton that advocated a realignment and triangulation under the re-branded "New Democrat" label.[30][31][32] The party adopted a synthesis of neoliberal economic policies with cultural liberalism, with the voter base after Reagan having shifted considerably to the right.[30] In an effort to appeal both to liberals and to fiscal conservatives, Democrats began to advocate for a balanced budget and market economy tempered by government intervention (mixed economy), along with a continued emphasis on social justice and affirmative action. The economic policy adopted by the Democratic Party, including the former Clinton administration, has been referred to as "Third Way".

The Democrats lost control of Congress in the election of 1994 to the Republican Party. Re-elected in 1996, Clinton was the first Democratic president since Franklin D. Roosevelt to be elected to two terms.[88]

21st century

2000s

In the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon as well as the growing concern over global warming, some of the party's key issues in the early 21st century have included combating terrorism while preserving human rights, expanding access to health care, labor rights, and environmental protection. Democrats regained majority control of both the House and the Senate in the 2006 elections. Barack Obama won the Democratic Party's nomination and was elected as the first African American president in 2008. Under the Obama presidency, the party moved forward reforms including an economic stimulus package, the Dodd–Frank financial reform act, and the Affordable Care Act.

2010s

In the 2010 midterm elections, the Democratic Party lost control of the House and lost its majority in state legislatures and state governorships. In the 2012 elections, President Obama was re-elected, but the party remained in the minority in the House of Representatives and lost control of the Senate in the 2014 midterm elections. After the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the Democratic Party transitioned into the role of an opposition party and held neither the presidency nor the Senate but won back a majority in the House in the 2018 midterm elections.[89] Democrats were extremely critical of President Trump, particularly his policies on immigration, healthcare, and abortion, as well as his response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[90][91][92]

2020s

Since the early 2010s, the party has shifted significantly to the left on social, cultural, and religious issues and attracted support from college-educated white Americans.[45]

In November 2020, Democrat Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election.[93] He began his term with narrow Democratic majorities in the House and the Senate.[94][95] The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was negotiated by Biden, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Joe Manchin, Kyrsten Sinema and other Democrats and is the largest allocation of funds for climate to date.[96][97]

Name and symbols

The Democratic-Republican Party splintered in 1824 into the short-lived National Republican Party and the Jacksonian movement which in 1828 became the Democratic Party. Under the Jacksonian era, the term "The Democracy" was in use by the party, but the name "Democratic Party" was eventually settled upon[98] and became the official name in 1844.[99] Members of the party are called "Democrats" or "Dems".

The term "Democrat Party" has also been in local use but has usually been used by opponents since 1952 as a disparaging term.

The most common mascot symbol for the party has been the donkey, or jackass.[100] Andrew Jackson's enemies twisted his name to "jackass" as a term of ridicule regarding a stupid and stubborn animal. However, the Democrats liked the common-man implications and picked it up too, therefore the image persisted and evolved.[101] Its most lasting impression came from the cartoons of Thomas Nast from 1870 in Harper's Weekly. Cartoonists followed Nast and used the donkey to represent the Democrats and the elephant to represent the Republicans.

In the early 20th century, the traditional symbol of the Democratic Party in Indiana, Kentucky, Oklahoma and Ohio was the rooster, as opposed to the Republican eagle. This symbol still appears on Oklahoma, Kentucky, Indiana, and West Virginia ballots.[102] The rooster was adopted as the official symbol of the national Democratic Party.[103] In New York, the Democratic ballot symbol is a five-pointed star.[104]

Although both major political parties (and many minor ones) use the traditional American colors of red, white, and blue in their marketing and representations, since election night 2000 blue has become the identifying color for the Democratic Party while red has become the identifying color for the Republican Party. That night, for the first time all major broadcast television networks used the same color scheme for the electoral map: blue states for Al Gore (Democratic nominee) and red states for George W. Bush (Republican nominee). Since then, the color blue has been widely used by the media to represent the party. This is contrary to common practice outside of the United States where blue is the traditional color of the right and red the color of the left.[105] For example, in Canada red represents the Liberals while blue represents the Conservatives. In the United Kingdom, red denotes the Labour Party and blue symbolizes the Conservative Party. Any use of the color blue to denote the Democratic Party prior to 2000 would be historically inaccurate and misleading. Since 2000, blue has also been used both by party supporters for promotional efforts—ActBlue, BuyBlue and BlueFund as examples—and by the party itself in 2006 both for its "Red to Blue Program", created to support Democratic candidates running against Republican incumbents in the midterm elections that year and on its official website.

In September 2010, the Democratic Party unveiled its new logo, which featured a blue D inside a blue circle. It was the party's first official logo; the donkey logo had only been semi-official.

Jefferson-Jackson Day is the annual fundraising event (dinner) held by Democratic Party organizations across the United States.[106] It is named after Presidents Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, whom the party regards as its distinguished early leaders.

The song "Happy Days Are Here Again" is the unofficial song of the Democratic Party. It was used prominently when Franklin D. Roosevelt was nominated for president at the 1932 Democratic National Convention and remains a sentimental favorite for Democrats today. For example, Paul Shaffer played the theme on the Late Show with David Letterman after the Democrats won Congress in 2006. "Don't Stop" by Fleetwood Mac was adopted by Bill Clinton's presidential campaign in 1992 and has endured as a popular Democratic song. The emotionally similar song "Beautiful Day" by the band U2 has also become a favorite theme song for Democratic candidates. John Kerry used the song during his 2004 presidential campaign and several Democratic Congressional candidates used it as a celebratory tune in 2006.[107][108]

As a traditional anthem for its presidential nominating convention, Aaron Copland's "Fanfare for the Common Man" is traditionally performed at the beginning of the Democratic National Convention.

Current structure and composition

National committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is responsible for promoting Democratic campaign activities. While the DNC is responsible for overseeing the process of writing the Democratic Platform, the DNC is more focused on campaign and organizational strategy than public policy. In presidential elections, it supervises the Democratic National Convention. The national convention is subject to the charter of the party and the ultimate authority within the Democratic Party when it is in session, with the DNC running the party's organization at other times. The DNC is chaired by Jaime Harrison.[109]

State parties

Each state also has a state committee, made up of elected committee members as well as ex officio committee members (usually elected officials and representatives of major constituencies), which in turn elects a chair. County, town, city, and ward committees generally are composed of individuals elected at the local level. State and local committees often coordinate campaign activities within their jurisdiction, oversee local conventions, and in some cases primaries or caucuses, and may have a role in nominating candidates for elected office under state law. Rarely do they have much funding, but in 2005 DNC Chairman Dean began a program (called the "50 State Strategy") of using DNC national funds to assist all state parties and pay for full-time professional staffers.[110]

Major party groups

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) assists party candidates in House races and its current chairman (selected by the party caucus) is Representative Sean Patrick Maloney of New York. Similarly, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC), headed by Senator Gary Peters of Michigan, raises funds for Senate races. The Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC), chaired by Majority Leader of the New York State Senate Andrea Stewart-Cousins, is a smaller organization that focuses on state legislative races. The DNC sponsors the College Democrats of America (CDA), a student-outreach organization with the goal of training and engaging a new generation of Democratic activists. Democrats Abroad is the organization for Americans living outside the United States. They work to advance the party's goals and encourage Americans living abroad to support the Democrats. The Young Democrats of America (YDA) and the High School Democrats of America (HSDA) are young adult and youth-led organizations respectively that attempt to draw in and mobilize young people for Democratic candidates but operates outside of the DNC. The Democratic Governors Association (DGA) is an organization supporting the candidacies of Democratic gubernatorial nominees and incumbents. Likewise, the mayors of the largest cities and urban centers convene as the National Conference of Democratic Mayors.[111]

Ideology

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

Upon foundation, the Democratic Party supported agrarianism and the Jacksonian democracy movement of President Andrew Jackson, representing farmers and rural interests and traditional Jeffersonian democrats.[112] Since the 1890s, especially in northern states, the party began to favor more liberal positions (the term "liberal" in this sense describes modern liberalism, rather than classical liberalism or economic liberalism). In recent exit polls, the Democratic Party has had broad appeal across all socio-ethno-economic demographics.[113][114][115]

Historically, the party has represented farmers, laborers, and religious and ethnic minorities as it has opposed unregulated business and finance and favored progressive income taxes. In foreign policy, internationalism (including interventionism) was a dominant theme from 1913 to the mid-1960s. In the 1930s, the party began advocating social programs targeted at the poor. The party had a fiscally conservative, pro-business wing, typified by Grover Cleveland and Al Smith, and a Southern conservative wing that shrank after President Lyndon B. Johnson supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The major influences for liberalism were labor unions (which peaked in the 1936–1952 era) and African Americans. Environmentalism has been a major component since the 1970s. The 21st century Democratic Party is predominantly a coalition of centrists, liberals, and progressives, with significant overlap between the three groups.[116] Political scientists characterize the Democratic Party as less ideologically cohesive than the Republican Party due to the broader diversity of coalitions than compose the Democratic Party.[16][17][15]

The Democratic Party, once dominant in the Southeastern United States, is now strongest in the Northeast (Mid-Atlantic and New England), the Great Lakes region, and the West Coast (including Hawaii). The party is also very strong in major cities (regardless of region).[117]

Centrists

Centrist Democrats, or New Democrats, are an ideologically centrist faction within the Democratic Party that emerged after the victory of Republican George H. W. Bush in the 1988 presidential election. They are an economically liberal and "Third Way" faction which dominated the party for around 20 years starting in the late 1980s after the United States populace turned much further to the political right. They are represented by organizations such as the New Democrat Network and the New Democrat Coalition. The New Democrat Coalition is a pro-growth and fiscally moderate congressional coalition.[118]

One of the most influential centrist groups was the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), a nonprofit organization that advocated centrist positions for the party. The DLC hailed President Bill Clinton as proof of the viability of "Third Way" politicians and a DLC success story. The DLC disbanded in 2011 and much of the former DLC is now represented in the think tank Third Way.[119]

Some Democratic elected officials have self-declared as being centrists, including former President Bill Clinton, former Vice President Al Gore, Senator Mark Warner, former Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell, former Senator Jim Webb, President Joe Biden, congresswoman Ann Kirkpatrick, and former congressman Dave McCurdy.[120][121]

The New Democrat Network supports socially liberal and fiscally moderate Democratic politicians and is associated with the congressional New Democrat Coalition in the House.[122] Suzan DelBene is the chair of the coalition,[120] and former senator and 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton was a member while in Congress.[123] In 2009, President Barack Obama was self-described as a New Democrat.[124]

Conservatives

A conservative Democrat is a member of the Democratic Party with conservative political views, or with views relatively conservative with respect to those of the national party. While such members of the Democratic Party can be found throughout the nation, actual elected officials are disproportionately found within the Southern states and to a lesser extent within rural regions of the United States generally, more commonly in the West. Historically, Southern Democrats were generally much more ideologically conservative than conservative Democrats are now.

Many conservative Southern Democrats defected to the Republican Party, beginning with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the general leftward shift of the party. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, Billy Tauzin of Louisiana, Kent Hance and Ralph Hall of Texas and Richard Shelby of Alabama are examples of this. The influx of conservative Democrats into the Republican Party is often cited as a reason for the Republican Party's shift further to the right during the late 20th century as well as the shift of its base from the Northeast and Midwest to the South.

Into the 1980s, the Democratic Party had a conservative element, mostly from the South and Border regions. Their numbers declined sharply as the Republican Party built up its Southern base. They were sometimes humorously called "Yellow dog Democrats", or "boll weevils" and "Dixiecrats". In the House, they form the Blue Dog Coalition, a caucus of conservatives and centrists willing to broker compromises with the Republican leadership. They have acted as a unified voting bloc in the past, giving its members some ability to change legislation, depending on their numbers in Congress.

Split-ticket voting was common among conservative Southern Democrats in the 1970s and 1980s. These voters supported conservative Democrats for local and statewide office while simultaneously voting for Republican presidential candidates.[125]

Liberals

Social liberals (modern liberals) are a large portion of the Democratic base. According to 2018 exit polls, liberals constituted 27% of the electorate, and 91% of American liberals favored the candidate of the Democratic Party.[126] White-collar college-educated professionals were mostly Republican until the 1950s, but they now compose a vital component of the Democratic Party.[127]

A large majority of liberals favor moving toward universal health care, with many supporting an eventual gradual transition to a single-payer system in particular. A majority also favor diplomacy over military action, stem cell research, the legalization of same-sex marriage, stricter gun control and environmental protection laws as well as the preservation of abortion rights. Immigration and cultural diversity are deemed positive as liberals favor cultural pluralism, a system in which immigrants retain their native culture in addition to adopting their new culture. They tend to be divided on free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and organizations, with some seeing them as more favorable to corporations than workers. Most liberals oppose increased military spending and the mixing of church and state.[128]

This ideological group differs from the traditional organized labor base. According to the Pew Research Center, a plurality of 41% resided in mass affluent households and 49% were college graduates, the highest figure of any typographical group. It was also the fastest growing typological group between the late 1990s and early 2000s.[128] Liberals include most of academia[129] and large portions of the professional class.[113][114][115]

Progressives

Progressives are the most left-leaning faction in the party and support strong business regulations, social programs, and workers' rights.[130][131] Progressive ideological stances have much in common with the programs of European countries as well as many East Asian countries. Many progressive Democrats are descendants of the New Left of Democratic presidential candidate Senator George McGovern of South Dakota whereas others were involved in the 2016 presidential candidacy of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. Progressives are often considered to have ideas similar to social democracy due to heavy inspiration from the nordic model, believing in federal top marginal income taxes ranging from 52% to 70%,[132] rent control,[133] increased collective bargaining power, a $15 an hour minimum wage, as well as free tuition and Universal Healthcare (typically Medicare for All).[134]

In 2014, progressive Senator Elizabeth Warren set out "Eleven Commandments of Progressivism": tougher regulation on corporations, affordable education, scientific investment and environmentalism, net neutrality, increased wages, equal pay for women, collective bargaining rights, defending social programs, same-sex marriage, immigration reform, and unabridged access to reproductive healthcare.[135] In addition, progressives strongly oppose political corruption and seek to advance electoral reforms such as campaign finance rules and voting rights protections.[136] Today, many progressives have made combating economic inequality their top priority.[137]

The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) is a caucus of progressive Democrats chaired by Pramila Jayapal of Washington.[138] Its members have included Representatives Dennis Kucinich of Ohio, John Conyers of Michigan, Jim McDermott of Washington, Barbara Lee of California, and Senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota. Senators Sherrod Brown of Ohio, Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin, Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, and Ed Markey of Massachusetts were members of the caucus when in the House of Representatives. While no Democratic senators currently belong to the CPC, independent Senator Bernie Sanders is a member.[139]

Political positions

- Economic policy

- Expand Social Security and safety net programs.[140]

- Increase top capital gains tax and dividend tax rates to above 28%.[141]

- Cut taxes for the working and middle classes as well as small businesses.[142]

- Change tax rules to not encourage shipping jobs overseas.[142]

- Increase federal and state minimum wages.[143]

- Modernize and expand access to public education and provide universal preschool education.[144]

- Support the goal of universal health care through a public health insurance option or expanding Medicare/Medicaid.[145]

- Increase investments in infrastructure development[146] as well as scientific and technological research.[147]

- Expand the use of renewable energy and diminish the use of fossil fuels.[148]

- Implement a carbon tax.[149]

- Uphold labor protections and the right to unionize.[150][151]

- Reform the student loan system and allow for refinancing student loans.[152]

- Make college more affordable.[143][153]

- Mandate equal pay for equal work regardless of gender, race, or ethnicity.[154]

- Social policy

- Decriminalize or legalize marijuana.[143]

- Uphold network neutrality.[155]

- Implement campaign finance reform and electoral reform.[38]

- Uphold voting rights and easy access to voting.[156][157]

- Support same-sex marriage and ban conversion therapy.[143]

- Allow legal access to abortions and women's reproductive health care.[146]

- Reform the immigration system and allow for a pathway to citizenship.[146]

- Support gun background checks and stricter gun control regulations.[146]

- Improve privacy laws and curtail government surveillance.[146]

- Oppose torture.[158][159]

- Abolish capital punishment.[160]

- Recognize and defend Internet freedom worldwide.[142]

Economic issues

Equal economic opportunity, a social safety net, and strong labor unions have historically been at the heart of Democratic economic policy.[34] The Democratic Party's economic policy positions, as measured by votes in Congress, tend to align with those of middle class.[161][162][163][164][165] Democrats support a progressive tax system, higher minimum wages, Social Security, universal health care, public education, and subsidized housing.[34] They also support infrastructure development and clean energy investments to achieve economic development and job creation.[166] Since the 1990s, the party has at times supported centrist economic reforms that cut the size of government and reduced market regulations.[167] The party has generally rejected both laissez-faire economics and market socialism, instead favoring Keynesian economics within a capitalist market-based system.[168]

Fiscal policy

Democrats support a more progressive tax structure to provide more services and reduce economic inequality by making sure that the wealthiest Americans pay the highest amount in taxes.[169] They oppose the cutting of social services, such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid,[170] believing it to be harmful to efficiency and social justice. Democrats believe the benefits of social services in monetary and non-monetary terms are a more productive labor force and cultured population and believe that the benefits of this are greater than any benefits that could be derived from lower taxes, especially on top earners, or cuts to social services. Furthermore, Democrats see social services as essential toward providing positive freedom, freedom derived from economic opportunity. The Democratic-led House of Representatives reinstated the PAYGO (pay-as-you-go) budget rule at the start of the 110th Congress.[171]

Minimum wage

The Democratic Party favors raising the minimum wage. The Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007 was an early component of the Democrats' agenda during the 110th Congress. In 2006, the Democrats supported six state ballot initiatives to increase the minimum wage and all six initiatives passed.[172]

In 2017, Senate Democrats introduced the Raise the Wage Act which would raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024.[173] In 2021, Democratic president Joe Biden proposed increasing the minimum wage to $15 by 2025.[174] In many states controlled by Democrats, the state minimum wage has been increased to a rate above the federal minimum wage.[175]

Health care

Democrats call for "affordable and quality health care" and favor moving toward universal health care in a variety of forms to address rising healthcare costs. Some Democratic politicians favor a single-payer program or Medicare for All, while others prefer creating a public health insurance option.[176]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010, has been one of the most significant pushes for universal health care. As of December 2019, more than 20 million Americans have gained health insurance under the Affordable Care Act.[177]

Education

Democrats favor improving public education by raising school standards and reforming the Head Start program. They also support universal preschool and expanding access to primary education, including through charter schools. They call for addressing student loan debt and reforms to reduce college tuition.[178] Other proposals have included tuition-free public universities and reform of standardized testing. Democrats have the long-term aim of having publicly funded college education with low tuition fees (like in much of Europe and Canada), which would be available to every eligible American student. Alternatively, they encourage expanding access to post-secondary education by increasing state funding for student financial aid such as Pell Grants and college tuition tax deductions.[179]

Environment

Democrats believe that the government should protect the environment and have a history of environmentalism. In more recent years, this stance has emphasized renewable energy generation as the basis for an improved economy, greater national security, and general environmental benefits.[184] The Democratic Party is substantially more likely than the Republican Party to support environmental regulation and policies that are supportive of renewable energy.[185][186]

The Democratic Party also favors expansion of conservation lands and encourages open space and rail travel to relieve highway and airport congestion and improve air quality and the economy as it "believe[s] that communities, environmental interests, and the government should work together to protect resources while ensuring the vitality of local economies. Once Americans were led to believe they had to make a choice between the economy and the environment. They now know this is a false choice".[187]

The foremost environmental concern of the Democratic Party is climate change. Democrats, most notably former Vice President Al Gore, have pressed for stern regulation of greenhouse gases. On October 15, 2007, Gore won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to build greater knowledge about man-made climate change and laying the foundations for the measures needed to counteract it.[188]

Renewable energy and fossil fuels

Democrats have supported increased domestic renewable energy development, including wind and solar power farms, in an effort to reduce carbon pollution. The party's platform calls for an "all of the above" energy policy including clean energy, natural gas and domestic oil, with the desire of becoming energy independent.[172] The party has supported higher taxes on oil companies and increased regulations on coal power plants, favoring a policy of reducing long-term reliance on fossil fuels.[189][190] Additionally, the party supports stricter fuel emissions standards to prevent air pollution.

Trade agreements

Many Democrats support fair trade policies when it comes to the issue of international trade agreements and some in the party have started supporting free trade in recent decades.[191] In the 1990s, the Clinton administration and a number of prominent Democrats pushed through a number of agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Since then, the party's shift away from free trade became evident in the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) vote, with 15 House Democrats voting for the agreement and 187 voting against.[192][193]

Social issues

The modern Democratic Party emphasizes social equality and equal opportunity. Democrats support voting rights and minority rights, including LGBT rights. The party championed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which for the first time outlawed segregation. Carmines and Stimson wrote "the Democratic Party appropriated racial liberalism and assumed federal responsibility for ending racial discrimination."[194][195][196]

Ideological social elements in the party include cultural liberalism, civil libertarianism, and feminism. Some Democratic social policies are immigration reform, electoral reform, and women's reproductive rights.

Equal opportunity

The Democratic Party supports equal opportunity for all Americans regardless of sex, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, or national origin. Many Democrats support affirmative action programs to further this goal. Democrats also strongly support the Americans with Disabilities Act to prohibit discrimination against people based on physical or mental disability. As such, the Democrats pushed as well the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, a disability rights expansion that became law.[197]

Voting rights

The party is very supportive of improving voting rights as well as election accuracy and accessibility.[198] They support extensions of voting time, including making election day a holiday. They support reforming the electoral system to eliminate gerrymandering, abolishing the electoral college, as well as passing comprehensive campaign finance reform.[38]

Abortion and reproductive rights

The Democratic Party believes that all women should have access to birth control and supports public funding of contraception for poor women. In its national platforms from 1992 to 2004, the Democratic Party has called for abortion to be "safe, legal and rare"—namely, keeping it legal by rejecting laws that allow governmental interference in abortion decisions and reducing the number of abortions by promoting both knowledge of reproduction and contraception and incentives for adoption. The wording changed in the 2008 platform. When Congress voted on the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act in 2003, Congressional Democrats were split, with a minority (including former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid) supporting the ban and the majority of Democrats opposing the legislation.[199]

The Democratic Party opposes attempts to reverse the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, which declared abortion covered by the constitutionally protected individual right to privacy under the Ninth Amendment; and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which lays out the legal framework in which government action alleged to violate that right is assessed by courts. As a matter of the right to privacy and of gender equality, many Democrats believe all women should have the ability to choose to abort without governmental interference. They believe that each woman, conferring with her conscience, has the right to choose for herself whether abortion is morally correct.

Former Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid was anti-abortion, while former President Barack Obama and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi favor abortion rights. Groups such as Democrats for Life of America represent the anti-abortion faction of the party while groups such as EMILY's List represent the abortion rights faction. A Newsweek poll from October 2006 found that 25% of Democrats were anti-abortion while a 69% majority was in favor of abortion rights.[200]

According to the 2020 Democratic Party platform, "Democrats believe every woman should be able to access high-quality reproductive health care services, including safe and legal abortion."[201]

Immigration

_-_restoration1.jpg.webp)

Many Democratic politicians have called for systematic reform of the immigration system such that residents that have come into the United States illegally have a pathway to legal citizenship. President Obama remarked in November 2013 that he felt it was "long past time to fix our broken immigration system," particularly to allow "incredibly bright young people" that came over as students to become full citizens. The Public Religion Research Institute found in a late 2013 study that 73% of Democrats supported the pathway concept, compared to 63% of Americans as a whole.[202]

In 2013, Democrats in the Senate passed S. 744, which would reform immigration policy to allow citizenship for illegal immigrants in the United States and improve the lives of all immigrants currently living in the United States.[203]

LGBT rights

The Democratic Party is supportive of LGBT rights. Most support for same-sex marriage in the United States has come from Democrats. Support for same-sex marriage has increased in the past decade according to ABC News. An April 2009 ABC News/Washington Post public opinion poll put support among Democrats at 62%[204] whereas a June 2008 Newsweek poll found that 42% of Democrats support same-sex marriage while 23% support civil unions or domestic partnership laws and 28% oppose any legal recognition at all.[205] A broad majority of Democrats have supported other LGBT-related laws such as extending hate crime statutes, legally preventing discrimination against LGBT people in the workforce and repealing the "don't ask, don't tell" military policy. A 2006 Pew Research Center poll of Democrats found that 55% supported gays adopting children with 40% opposed while 70% support gays in the military, with only 23% opposed.[206] Gallup polling from May 2009 stated that 82% of Democrats support open enlistment.[207]

The 2004 Democratic National Platform stated that marriage should be defined at the state level and it repudiated the Federal Marriage Amendment.[208] While not stating support of same-sex marriage, the 2008 platform called for repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, which banned federal recognition of same-sex marriage and removed the need for interstate recognition, supported antidiscrimination laws and the extension of hate crime laws to LGBT people and opposed "don't ask, don't tell".[209] The 2012 platform included support for same-sex marriage and for the repeal of DOMA.[39]

On May 9, 2012, Barack Obama became the first sitting president to say he supports same-sex marriage.[210][211] Previously, he had opposed restrictions on same-sex marriage such as the Defense of Marriage Act, which he promised to repeal,[212] California's Prop 8,[213] and a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage (which he opposed saying that "decisions about marriage should be left to the states as they always have been"),[214] but also stated that he personally believed marriage to be between a man and a woman and that he favored civil unions that would "give same-sex couples equal legal rights and privileges as married couples".[212] Earlier, when running for the Illinois Senate in 1996 he said, "I favor legalizing same-sex marriages, and would fight efforts to prohibit such marriages".[215] John Kerry, Democratic presidential candidate in 2004, did not support same-sex marriage. Former presidents Bill Clinton[216] and Jimmy Carter[217] and former vice presidents Al Gore[218] and Walter Mondale[219] also support gay marriage. President Joe Biden has been in favor of same-sex marriage since 2012 when he became the highest-ranking government official to support it.[220]

Puerto Rico

The 2016 Democratic Party platform declares: "We are committed to addressing the extraordinary challenges faced by our fellow citizens in Puerto Rico. Many stem from the fundamental question of Puerto Rico's political status. Democrats believe that the people of Puerto Rico should determine their ultimate political status from permanent options that do not conflict with the Constitution, laws, and policies of the United States. Democrats are committed to promoting economic opportunity and good-paying jobs for the hardworking people of Puerto Rico. We also believe that Puerto Ricans must be treated equally by Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs that benefit families. Puerto Ricans should be able to vote for the people who make their laws, just as they should be treated equally. All American citizens, no matter where they reside, should have the right to vote for the president of the United States. Finally, we believe that federal officials must respect Puerto Rico's local self-government as laws are implemented and Puerto Rico's budget and debt are restructured so that it can get on a path towards stability and prosperity".[146]

Gun control

With a stated goal of reducing crime and homicide, the Democratic Party has introduced various gun control measures, most notably the Gun Control Act of 1968, the Brady Bill of 1993 and Crime Control Act of 1994. However, some Democrats, especially rural, Southern, and Western Democrats, favor fewer restrictions on firearm possession and warned the party was defeated in the 2000 presidential election in rural areas because of the issue.[222] In the national platform for 2008, the only statement explicitly favoring gun control was a plan calling for renewal of the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban.[223] In 2022, Democratic president Joe Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which among other things expanded background checks and provided incentives for states to pass red flag laws.[224]

Death penalty

The Democratic Party currently opposes the death penalty.[160] Although most Democrats in Congress have never seriously moved to overturn the rarely used federal death penalty, both Russ Feingold and Dennis Kucinich have introduced such bills with little success. Democrats have led efforts to overturn state death penalty laws, particularly in New Jersey and in New Mexico. They have also sought to prevent the reinstatement of the death penalty in those states which prohibit it, including Massachusetts and New York. During the Clinton administration, Democrats led the expansion of the federal death penalty. These efforts resulted in the passage of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, signed into law by President Clinton, which heavily limited appeals in death penalty cases. In 1972, the Democratic Party platform called for the abolition of capital punishment.[225] In 1992, 1993 and 1995, Democratic Texas Congressman Henry González unsuccessfully introduced the Death Penalty Abolition Amendment which prohibited the use of capital punishment in the United States. Democratic Missouri Congressman William Lacy Clay, Sr. cosponsored the amendment in 1993.

During his Illinois Senate career, former President Barack Obama successfully introduced legislation intended to reduce the likelihood of wrongful convictions in capital cases, requiring videotaping of confessions. When campaigning for the presidency, Obama stated that he supports the limited use of the death penalty, including for people who have been convicted of raping a minor under the age of 12, having opposed the Supreme Court's ruling in Kennedy v. Louisiana that the death penalty was unconstitutional in child rape cases.[226] Obama has stated that he thinks the "death penalty does little to deter crime" and that it is used too frequently and too inconsistently.[227]

In June 2016, the Democratic Platform Drafting Committee unanimously adopted an amendment to abolish the death penalty.[228]

Torture

Many Democrats are opposed to the use of torture against individuals apprehended and held prisoner by the United States military and hold that categorizing such prisoners as unlawful combatants does not release the United States from its obligations under the Geneva Conventions. Democrats contend that torture is inhumane, damages the United States' moral standing in the world, and produces questionable results. Democrats are largely against waterboarding.[229]

Torture became a divisive issue in the party after Barack Obama was elected president.[230]

Patriot Act

Many Democrats are opposed to the Patriot Act, but when the law was passed most Democrats were supportive of it and all but two Democrats in the Senate voted for the original Patriot Act legislation in 2001. The lone nay vote was from Russ Feingold of Wisconsin as Mary Landrieu of Louisiana did not vote.[231] In the House, the Democrats voted for the Act by 145 yea and 62 nay. Democrats were split on the renewal in 2006. In the Senate, Democrats voted 34 for the 2006 renewal and nine against. In the House, Democrats voted 66 voted for the renewal and 124 against.[232]

Privacy

The Democratic Party believes that individuals should have a right to privacy. For example, many Democrats have opposed the NSA warrantless surveillance of American citizens.

Some Democratic officeholders have championed consumer protection laws that limit the sharing of consumer data between corporations. Democrats have opposed sodomy laws since the 1972 platform which stated that "Americans should be free to make their own choice of life-styles and private habits without being subject to discrimination or prosecution",[233] and believe that government should not regulate consensual noncommercial sexual conduct among adults as a matter of personal privacy.[234]

Foreign policy issues

The foreign policy of the voters of the two major parties has largely overlapped since the 1990s. A Gallup poll in early 2013 showed broad agreement on the top issues, albeit with some divergence regarding human rights and international cooperation through agencies such as the United Nations.[235]

In June 2014, the Quinnipiac Poll asked Americans which foreign policy they preferred:

A) The United States is doing too much in other countries around the world, and it is time to do less around the world and focus more on our own problems here at home. B) The United States must continue to push forward to promote democracy and freedom in other countries worldwide because these efforts make our own country more secure.

Democrats chose A over B by 65% to 32%; Republicans chose A over B by 56% to 39%; and independents chose A over B by 67% to 29%.[236]

Iraq War

In 2002, Congressional Democrats were divided on the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq: 147 voted against it (21 in the Senate and 126 in the House) and 110 voted for it (29 in the Senate and 81 in the House). Since then, many prominent Democrats, such as former senator John Edwards, have expressed regret about this decision and have called it a mistake while others, such as Senator Hillary Clinton, have criticized the conduct of the war yet not repudiated their initial vote for it (though Clinton later went on to repudiate her stance during the 2008 primaries). Referring to Iraq, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid declared in April 2007 the war to be "lost" while other Democrats (especially during the 2004 presidential election cycle) accused the President of lying to the public about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Among lawmakers, Democrats are the most vocal opponents of Operation Iraqi Freedom and campaigned on a platform of withdrawal ahead of the 2006 midterm elections.

A March 2003 CBS News poll taken a few days before the invasion of Iraq found that 34% of Democrats nationwide would support it without United Nations backing, 51% would support it only with its backing and 14% would not support it at all.[237] The Los Angeles Times stated in early April 2003 that 70% of Democrats supported the decision to invade while 27% opposed it.[238] The Pew Research Center stated in August 2007 that opposition increased from 37% during the initial invasion to 74%.[239] In April 2008, a CBS News poll found that about 90% of Democrats disapprove of the Bush administration's conduct and want to end the war within the next year.[240]

Democrats in the House of Representatives near-unanimously supported a non-binding resolution disapproving of President Bush's decision to send additional troops into Iraq in 2007. Congressional Democrats overwhelmingly supported military funding legislation that included a provision that set "a timeline for the withdrawal of all US combat troops from Iraq" by March 31, 2008, but also would leave combat forces in Iraq for purposes such as targeted counter-terrorism operations.[241][242] After a veto from the President and a failed attempt in Congress to override the veto,[243] the U.S. Troop Readiness, Veterans' Care, Katrina Recovery, and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act, 2007 was passed by Congress and signed by the President after the timetable was dropped. Criticism of the Iraq War subsided after the Iraq War troop surge of 2007 led to a dramatic decrease in Iraqi violence. The Democratic-controlled 110th Congress continued to fund efforts in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Presidential candidate Barack Obama advocated a withdrawal of combat troops within Iraq by late 2010 with a residual force of peacekeeping troops left in place.[244] He stated that both the speed of withdrawal and the number of troops left over would be "entirely conditions-based".[244]

On February 27, 2009, President Obama announced: "As a candidate for president, I made clear my support for a timeline of 16 months to carry out this drawdown, while pledging to consult closely with our military commanders upon taking office to ensure that we preserve the gains we've made and protect our troops ... Those consultations are now complete, and I have chosen a timeline that will remove our combat brigades over the next 18 months".[245] Around 50,000 non-combat-related forces would remain.[245] Obama's plan drew wide bipartisan support, including that of defeated Republican presidential candidate Senator John McCain.[245]

Iran sanctions

The Democratic Party has been critical of the Iran's nuclear weapon program and supported economic sanctions against the Iranian government. In 2013, the Democratic-led administration worked to reach a diplomatic agreement with the government of Iran to halt the Iranian nuclear weapon program in exchange for international economic sanction relief.[246] As of 2014, negotiations had been successful and the party called for more cooperation with Iran in the future.[247] In 2015, the Obama administration agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which provides sanction relief in exchange for international oversight of the Iranian nuclear program. In February 2019, the Democratic National Committee passed a resolution calling on the United States to re-enter the JCPOA, which President Trump withdrew from in 2018.[248]

Invasion of Afghanistan

Democrats in the House of Representatives and in the Senate near-unanimously voted for the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists against "those responsible for the recent attacks launched against the United States" in Afghanistan in 2001, supporting the NATO coalition invasion of the nation. Most elected Democrats continue to support the Afghanistan conflict and some, such as a Democratic National Committee spokesperson, have voiced concerns that the Iraq War shifted too many resources away from the presence in Afghanistan.[249][250] Since 2006, Democratic candidate Barack Obama has called for a "surge" of troops into Afghanistan.[250] As president, Obama sent a "surge" force of additional troops to Afghanistan. Troop levels were 94,000 in December 2011 and kept falling, with a target of 68,000 by fall 2012. Obama planned to bring all the troops home by 2014.[251]

Support for the war among the American people has diminished over time and many Democrats have changed their opinion and now oppose a continuation of the conflict.[252][253] In July 2008, Gallup found that 41% of Democrats called the invasion a "mistake" while a 55% majority disagreed. In contrast, Republicans were more supportive of the war. The survey described Democrats as evenly divided about whether or not more troops should be sent—56% support it if it would mean removing troops from Iraq and only 47% support it otherwise.[253] A CNN survey in August 2009 stated that a majority of Democrats now oppose the war. CNN polling director Keating Holland said: "Nearly two thirds of Republicans support the war in Afghanistan. Three quarters of Democrats oppose the war".[252] An August 2009 Washington Post poll found similar results, and the paper stated that Obama's policies would anger his closest supporters.[254]

Israel

The Democratic Party has both recently and historically supported Israel.[255][256] A 2008 Gallup poll found that 64% of Americans have a favorable image of Israel while only 16% say that they have a favorable image of the Palestinian Authority.[255] A pro-Israel view is held by the party leadership although some Democrats, including former President Jimmy Carter, have criticized Israel.[256]

The 2008 Democratic Party platform acknowledges a "special relationship with Israel, grounded in shared interests and shared values, and a clear, strong, fundamental commitment to the security of Israel, our strongest ally in the region and its only established democracy." It also included:

It is in the best interests of all parties, including the United States, that we take an active role to help secure a lasting settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with a democratic, viable Palestinian state dedicated to living in peace and security side by side with the Jewish State of Israel. To do so, we must help Israel identify and strengthen those partners who are truly committed to peace while isolating those who seek conflict and instability, and stand with Israel against those who seek its destruction. The United States and its Quartet partners should continue to isolate Hamas until it renounces terrorism, recognizes Israel's right to exist, and abides by past agreements. Sustained American leadership for peace and security will require patient efforts and the personal commitment of the President of the United States. The creation of a Palestinian state through final status negotiations, together with an international compensation mechanism, should resolve the issue of Palestinian refugees by allowing them to settle there, rather than in Israel. All understand that it is unrealistic to expect the outcome of final status negotiations to be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949. Jerusalem is and will remain the capital of Israel. The parties have agreed that Jerusalem is a matter for final status negotiations. It should remain an undivided city accessible to people of all faiths.[257]

A January 2009 Pew Research Center study found that when asked "which side do you sympathize with more", 42% of Democrats and 33% of liberals (a plurality in both groups) sympathize most with the Israelis. Around half of all political moderates or independents sided with Israel.[258] The years leading up to the 2016 election have brought more discussion of the party's stance on Israel as polls reported declining support for Israel among the party faithful.[259] Gallup suggested that the decline in support might be due to tensions between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Barack Obama.[259]

The rise of the progressive Bernie Sanders-aligned faction of the party, which tends to trend more pro-Palestine, is also likely responsible for the decline in support for Israel. A 2016 Pew Research poll found that while Clinton supporters sympathized more with Israel than Palestinians by a 20-point margin, Sanders supporters sympathized more with Palestinians than with Israel by a 6-point margin.[260] In June 2016, DNC members voted against an amendment to the party platform proposed by Sanders supporter James Zogby calling for an "end to occupation and illegal settlements".[261] In August 2018, Rashida Tlaib, who supports a one-state solution,[262] and Ilhan Omar, who has referred to Israel as an "apartheid regime"[263] won Democratic primaries in Michigan and Minnesota. In November 2018, shortly after being elected to Congress, Omar came out in support of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign against Israel.[264]

Composition

By income and class

The relationship between income, class, and partisan support has changed dramatically in recent years.[266]

Historically, members of the working class and the poor have tended to support the Democratic Party, although this has changed substantially, with affluent voters rapidly trending towards the Democratic Party and poorer voters rapidly trending towards to the Republican Party.[267] Since the mid-2010s, affluent white voters have been more likely to vote for the Democratic Party.[48][268] Eric Levitz of New York Magazine writes that:[48]

Blue America is an increasingly wealthy and well-educated place. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, Americans without college degrees were more likely than university graduates to vote Democratic. But that gap began narrowing in the late 1960s before finally flipping in 2004... A more educated Democratic coalition is, naturally, a more affluent one... In every presidential election from 1948 to 2012, white voters in the top 5 percent of America's income distribution were more Republican than those in the bottom 95 percent. Now, the opposite is true: Among America's white majority, the rich voted to the left of the middle class and the poor in 2016 and 2020, while the poor voted to the right of the middle class and the rich.

Since 1980,[269] there has been a significant decline in support for the Democratic Party among white working class voters.[270][271][272] Since the 2010s, similar trends have been observed among working class minority groups, particularly among those who are Hispanic.[46][47][54][55][268] Economic insecurity makes many working-class people supportive of redistributing income and wealth. However, many of them differ from liberals in having socially conservative views. Working class Democrats tend to be more religious and more likely to belong to an ethnic minority.[51][55][266][268]

In the 2020 presidential election, Democratic-plurality voting areas composed 70% of the total United States GDP.[265]

According to The New Yorker, by 2022 this political realignment had made "the most affluent congressional districts in the country... largely represented by Democrats".[266]

Professionals

Professionals, those who have a college education and those whose work revolves around the conception of ideas, have tended to support the Democratic Party since 2000. While the professional class was once a stronghold of the Republican Party, it has become increasingly in favor of the Democratic Party. Support for Democratic candidates among professionals may be traced to the prevalence of liberal cultural values among this group:[273]

Professionals, who are, roughly speaking, college-educated producers of services and ideas, used to be the most staunchly Republican of all occupational groups ... now chiefly working for large corporations and bureaucracies rather than on their own, and heavily influenced by the environmental, civil-rights, and feminist movements—began to vote Democratic. In the four elections from 1988 to 2000, they backed Democrats by an average of 52 percent to 40 percent.

— John B. Judis and Ruy Teixeira, The American Prospect, June 19, 2007

The highly educated constitute an important part of the Democratic voter base. The party has strong support among scientists, with 55% identifying as Democrats, 32% as independents, and 6% as Republicans in a 2009 study.[274] Those with a college education have become increasingly Democratic in the 1992,[275] 1996,[275] 2000,[113] 2004,[114] and 2008[276] elections. In exit polls for the 2018 elections, 65% of those with a graduate degree said they voted Democratic, and Democrats won college graduates overall by a 20-point margin.[126]

Labor

Since the 1930s, a critical component of the Democratic Party coalition has been organized labor. Labor unions supply a great deal of the money, grass roots political organization, and voters for the party. Democrats are far more likely to be represented by unions, although union membership has declined in general during the last few decades. This trend is depicted in the following graph from the book Democrats and Republicans—Rhetoric and Reality.[277] It is based on surveys conducted by the National Election Studies (NES).

The three most significant labor groupings in the Democratic coalition today are the AFL–CIO and Change to Win labor federations as well as the National Education Association, a large, unaffiliated teachers' union. Important issues for labor unions include supporting industrial policy that sustains unionized manufacturing jobs, raising the minimum wage, and promoting broad social programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

In the 2020 presidential election, 57% of union households voted for Joe Biden.[52]

Younger Americans

Younger Americans, including millennials and Generation Z, tend to vote mostly for Democratic candidates in recent years.[49]