Benzydamine

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Difflam, Tantum |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <20% |

| Elimination half-life | 13 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.354 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

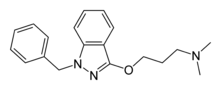

| Formula | C19H23N3O |

| Molar mass | 309.413 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

| (verify) | |

Benzydamine (also known as Tantum Verde and branded in some countries as Difflam and Septabene), available as the hydrochloride salt, is a locally acting nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with local anaesthetic and analgesic properties for pain relief and anti-inflammatory treatment of inflammatory conditions of the mouth and throat.[1] It falls under class of chemicals known as indazole.

History

It was synthesized in Italy in 1964 and marketed in 1966.[2]

Uses

Medical

- Odontostomatology: gingivitis, stomatitis, glossitis, aphthous ulcers, dental surgery and oral ulceration due to radiation therapy.

- Otorhinolaryngology: glandular fever, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, post-tonsillectomy, radiation or intubation mucositis.

It may be used alone or as an adjunct to other therapy giving the possibility of increased therapeutic effect with little risk of interaction.

In some markets, the drug is supplied as an over-the-counter cream (Lonol in Mexico from Boehringer Ingelheim) used for topical treatment of musculoskeletal system disorders: sprains, strains, bursitis, tendinitis, synovitis, myalgia, periarthritis.

Recreational

Benzydamine has been used recreationally. In overdosages it acts as a deliriant and CNS stimulant.[3] Such use, particularly among teenagers, has been reported in Poland,[3] Brazil[4][5] and Romania.

Contraindications

There are no contraindications to the use of benzydamine except for known hypersensitivity.

Side effects

Benzydamine is well tolerated. Occasionally oral tissue numbness or stinging sensations may occur, as well as itching, a skin rash, skin swelling or redness, difficulty breathing and wheezing.

Pharmacology

It selectively binds to inflamed tissues (Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor) and is normally free of adverse systemic effects. Unlike other NSAIDs, it does not inhibit cyclooxygenase or lipooxygenase, and is not ulcerogenic.[3][6] It has powerful reinforcing effect and has cross sensitization with drugs of abuse such as heroin and cocaine in animals. It is hypothesized that it has cannabinoid agonistic activity.[7]

Pharmacokinetic

Benzydamine is poorly absorbed through skin[8] and vagina.[9]

Synthesis

Synthesis starts with the reaction of the N-benzyl derivative from methyl anthranilate with nitrous acid to give the N-nitroso derivative. Reduction by means of sodium thiosulfate leads to the transient hydrazine (3), which undergoes spontaneous internal hydrazide formation. Treatment of the enolate of this amide with 3-chloro-1-dimethylamkino propane gives benzydamine (5). Please note there is an error in this section: US3318905 states that the nitroso derivative is reduced with sodium hydrosulfite (sodium dithionite) and not with sodium hyposulfite (sodium thiosulfate), as shown in the above scheme and stated in text.

An interesting alternative synthesis of this substance starts by sequential reaction of N-benzylaniline with phosgene, and then with sodium azide to product the corresponding carbonyl azide. On heating, nitrogen is evolved and a separatable mixture of nitrene insertion product and the desired ketoindazole # results. The latter reaction appears to be a Curtius rearrangement type product to produce an N-isocyanate #, which then cyclizes. Alkylation of the enol with sodium methoxide and 3-dimethylaminopropyl chloride gives benzydamine.

Alternatively, use of chloroacetamide in the alkylation step followed by acid hydrolysis produces bendazac instead.

Research

Studies indicate that benzydamine has notable in vitro antibacterial activity and also shows synergism in combination with other antibiotics, especially tetracyclines, against antibiotic-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[13][14]

It also has some cannabinoid activity in rats but has not been tested in humans.[7] It is also hypothesized to act on 5-HT2A receptors due to its structural similarity with serotonin.[2]

See also

- AB-FUBINACA

- Pravadoline

- GW-405,833

- Bendazac

References

- ↑ Turnbull RS (February 1995). "Benzydamine Hydrochloride (Tantum) in the management of oral inflammatory conditions". Journal. 61 (2): 127–34. PMID 7600413.

- 1 2 "DEXTROMETHORPHAN AND BENZYDAMINE'S USE AND MISUSE".

- 1 2 3 Anand JS, Glebocka ML, Korolkiewicz RP (2007). "Recreational abuse with benzydamine hydrochloride (tantum rosa)". Clinical Toxicology. 45 (2): 198–9. doi:10.1080/15563650600981210. PMID 17364645.

- ↑ Opaleye ES, Noto AR, Sanchez Z, Moura YG, Galduróz JC, Carlini EA (September 2009). "Recreational use of benzydamine as a hallucinogen among street youth in Brazil". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 31 (3): 208–13. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462009000300005. PMID 19784487.

- ↑ Mota DM, Costa AA, Teixeira C, Bastos AA, Dias MF (May 2010). "Use abusive of benzydamine in Brazil: an overview in pharmacovigilance". Ciencia & Saude Coletiva (in Portuguese). 15 (3): 717–24. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232010000300014. PMID 20464184.

- ↑ Müller-Peddinghaus R (May 1987). "New pharmacologic and biochemical findings on the mechanism of action of the non-steroidal antiphlogistic, benzydamine. A synopsis". Arzneimittel-Forschung (in German). 37 (5A): 635–45. PMID 3304305.

- 1 2 Avvisati R, Meringolo M, Stendardo E, Malavasi E, Marinelli S, Badiani A (March 2018). "Intravenous self-administration of benzydamine, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug with a central cannabinoidergic mechanism of action" (PDF). Addiction Biology. 23 (2): 610–619. doi:10.1111/adb.12516. PMID 28429885. S2CID 206970991.

- ↑ Baldock GA, Brodie RR, Chasseaud LF, Taylor T, Walmsley LM, Catanese B (October 1991). "Pharmacokinetics of benzydamine after intravenous, oral, and topical doses to human subjects". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 12 (7): 481–92. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510120702. PMID 1932611. S2CID 42167110.

- ↑ Maamer M, Aurousseau M, Colau JC (1987). "Concentration of benzydamine in vaginal mucosa following local application: an experimental and clinical study". International Journal of Tissue Reactions. 9 (2): 135–45. PMID 3610512.

- 1 2 Palazzo G, Corsi G, Baiocchi L, Silvestrini B (January 1966). "Synthesis and pharmacological properties of 1-substituted 3-dimethylaminoalkoxy-1H-indazoles". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (1): 38–41. doi:10.1021/jm00319a009. PMID 5958958.

- ↑ FR 1382855; Palazzo, U.S. Patent 3,318,905 (1964, 1967 both to Angelini Francesco).

- ↑ Baiocchi L, Corsi G, Palazzo G (1965). "Ricerche nel campo degli indazoli.—Nota 1. Sulla ciclizzazione termica di azidi di acidi N-aril-N-benzil-carbamici". Annali di Chimica. 55: 116–25.

- ↑ Fanaki NH, el-Nakeeb MA (December 1992). "Antimicrobial activity of benzydamine, a non-steroid anti-inflammatory agent". Journal of Chemotherapy. 4 (6): 347–52. doi:10.1080/1120009X.1992.11739190. PMID 1287137.

- ↑ Fanaki NH, El-Nakeeb MA (March 1996). "Antibacterial activity of benzydamine and antibiotic-benzydamine combinations against multifold resistant clinical isolates". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 46 (3): 320–3. PMID 8901158.

External links

- "Benzydamine oral rinse". Medicinenet.

- "Difflam spray (benzydamine)". Net Doctor, UK. 8 March 2020.

- "Tantum Verde (benzydamine)". Carysfort Healthcare Limited, Ireland. Archived from the original on 2015-11-25.