Adult polyglucosan body disease

| Adult polyglucosan disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: AFBD | |

| |

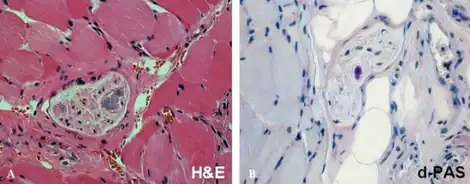

| a,b)Adult polyglucosan body disease-Pathological findings revealed a few polyglucosan bodies in peripheral nerves of perimysium | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD) is a rare genetic glycogen storage disorder caused by an inborn error of metabolism. Symptoms can emerge any time after the age of 30; early symptoms include trouble controlling urination, trouble walking, and lack of sensation in the legs. People eventually develop dementia.

A person inherits loss-of-function mutations in the GBE1 gene from each parent, and the lack of glycogen branching enzyme (the protein encoded by GBE1) leads to buildup of unbranched glycogen in cells, which harms neurons more than other kinds of cells.

Most people first go to the doctor due to trouble with urination. The condition is diagnosed by gathering symptoms, a neurological examination, laboratory tests including genetic testing, and medical imaging. As of 2015 there was no cure or treatment, but the symptoms could be managed. People diagnosed with APBD can live a long time after diagnosis, but will probably die earlier than people without the condition.

Signs and symptoms

Adult polyglucosan body disease is a condition that affects the nervous system. People with this condition have problems walking due to reduced sensation in their legs (peripheral neuropathy) and progressive muscle weakness and stiffness (spasticity). Damage to the nerves that control bladder function (neurogenic bladder) causes progressive difficulty in controlling the flow of urine. About half of people with adult polyglucosan body disease experience dementia.[1] Most people with the condition first complain of bladder issues.[2]

People with adult polyglucosan body disease typically first experience signs and symptoms related to the condition between ages 30 and 60.[1]

Causes

APBD is an autosomal recessive disorder that is caused when a person inherits genes from both parents containing one or more loss-of-function mutations in the gene GBE1 which encodes for glycogen branching enzyme, also called 1,4-alpha-glucan-branching enzyme.[3]

Mechanism

The GBE1 gene provides instructions for making the glycogen branching enzyme. This enzyme is involved in the production of a complex sugar called glycogen, which is a major source of stored energy in the body. Most GBE1 gene mutations result in a shortage (deficiency) of the glycogen branching enzyme, which leads to the production of abnormal glycogen molecules. These abnormal glycogen molecules, called polyglucosan bodies, accumulate within cells and cause damage. Neurons appear to be particularly vulnerable to the accumulation of polyglucosan bodies in people with this disorder, leading to impaired neuronal function.[1]

Some mutations in the GBE1 gene that cause adult polyglucosan body disease do not result in a shortage of glycogen branching enzyme. In people with these mutations, the activity of this enzyme is normal. How mutations cause the disease in these individuals is unclear. Other people with adult polyglucosan body disease do not have identified mutations in the GBE1 gene. In these individuals, the cause of the disease is unknown.[1]

Diagnosis

Along with evaluation of the symptoms and a neurological examination, a diagnosis can be made based on genetic testing. Whether or not a person is making sufficient amounts of functional glycogen branching enzyme can be determined by taking a skin biopsy and testing for activity of the enzyme. Examination of tissue biopsied from the sural nerve under a microscope can reveal the presence of polyglucosan bodies. There will also be white matter changes visible in a magnetic resonance imaging scans.[4]

Classification

Adult polyglucosan body disease is an orphan disease and a glycogen storage disorder that is caused by an inborn error of metabolism, that affects the central and peripheral nervous systems.[4][5]

The condition in newborns caused by the same mutations is called glycogen storage disease type IV.[3]

Prevention

APBD can only be prevented if parents undergo genetic screening to understand their risk of producing a child with the condition; if in vitro fertilization is used, then preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be done to identify fertilized eggs that do not carry two copies of mutated GBE1.[4]

Management

As of 2015 there was no cure for APDB, instead symptoms are managed.[6] There are various approaches to managing neurogenic bladder dysfunction, physical therapy and mobility aids to help with walking, and dementia can be managed with occupational therapy, counseling and drugs.[3] Presently a number of promising research initiatives are underway in universities and hospitals in the United States, Canada, and Israel. These studies are in need of funding but due to the small number of known cases both research funding and participation is small. It is estimated that there are upwards of 12,000 cases in the United States, most of which are undiagnosed.

Outcomes

The rate of progression varies significantly from person to person.[4][6]

There is not good data on outcomes; it appears that APBD likely leads to earlier death, but people with APBD can live many years after diagnosis with relatively good quality of life.[4]

Epidemiology

The prevalence is unknown; about 70 cases had been reported in the medical literature as of 2016.[1] As of 2016 the largest set of case studies included 50 people; about 70% of them were of Ashkenazic Jewish descent.[3][7]

Society and culture

A person with APBD named Gregory Weiss created a foundation, the Adult Polyglucosan Body Disease Research Foundation, to fund research into the disease and its management.[2][8]

Research directions

In 2015 the first transgenic mouse that appeared to be a useful model organism for studying APBD was published.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Adult polyglucosan body disease". NIH Genetics Home Reference. July 2016. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- 1 2 DiMauro, S; Spiegel, R (October 2011). "Progress and problems in muscle glycogenoses". Acta Myologica. 30 (2): 96–102. PMC 3235878. PMID 22106711.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McKusick, Victor A.; Kniffin, Cassandra L. (May 2, 2016). "OMIM Entry 263570 - Polyglucosan body neuropathy, adult form". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Johns Hopkins University. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Klein, Christopher J. (December 19, 2013). "Adult Polyglucosan Body Disease". In Pagon, RA; et al. (eds.). GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Adult polyglucosan body disease". Orphanet. September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- 1 2 "Adult Polyglucosan Body Disease". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ Mochel; et al. (September 2012). "Adult polyglucosan body disease: Natural History and Key Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings". Annals of Neurology. 72 (3): 433–41. doi:10.1002/ana.23598. PMC 4329926. PMID 23034915.

- ↑ "Adult Polyglucosan Body Disease Research Foundation (APBDRF)". Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Health and Human Services document: "Adult polyglucosan body disease".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Health and Human Services document: "Adult polyglucosan body disease".

External links

| Classification |

|---|