Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia

| Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia | |

|---|---|

| |

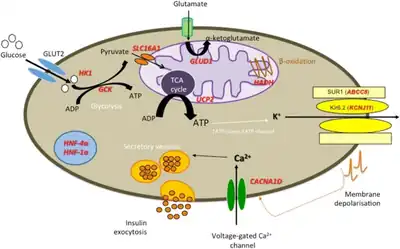

| Diagrammatic representation of β-cell function, genetic defects are included in red.[1] | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia describes the condition and effects of low blood glucose caused by excessive insulin. Hypoglycemia due to excess insulin is the most common type of serious hypoglycemia. It can be due to endogenous or injected insulin.

Types

There are several genetic forms of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia:

| Type | OMIM | Gene | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| HHF1 | 256450 | ABCC8 | 11p15.1 |

| HHF2 | 601820 | KCNJ11 | 11p15.1 |

| HHF3 | 602485 | GCK | 7p15-p13 |

| HHF4 | 609975 | HADH | 4q22-q26 |

| HHF5 | 609968 | INSR | 19p13.2 |

| HHF6 | 606762 | GLUD1 | 10q23.3 |

| HHF7 | 610021 | SLC16A1 | 1p13.2-p12 |

Signs and symptoms

Manifestations of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia vary by age and severity of the hypoglycemia. In general, most signs and symptoms can be attributed to (1) the effects on the brain of insufficient glucose (neuroglycopenia) or (2) to the adrenergic response of the autonomic nervous system to hypoglycemia. A few miscellaneous symptoms are harder to attribute to either of these causes. In most cases, all effects are reversed when normal glucose levels are restored.

There are uncommon cases of more persistent harm, and rarely even death due to severe hypoglycemia of this type. One reason hypoglycemia due to excessive insulin can be more dangerous is that insulin lowers the available amounts of most alternate brain fuels, such as ketones. Brain damage of various types ranging from stroke-like focal effects to impaired memory and thinking can occur. Children who have prolonged or recurrent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in infancy can suffer harm to their brains and may be developmentally delayed.

Causes

Hypoglycemia due to endogenous insulin can be congenital or acquired, apparent in the newborn period, or many years later. The hypoglycemia can be severe and life-threatening or a minor, occasional nuisance. By far the most common type of severe but transient hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia occurs accidentally in persons with type 1 diabetes who take insulin.

- Hypoglycemia due to endogenous insulin

- Congenital hyperinsulinism

- Transient neonatal hyperinsulinism (mechanism not known)

- Focal hyperinsulinism (KATP channel disorders)

- Paternal SUR1 mutation with clonal loss of heterozygosity of 11p15

- Paternal Kir6.2 mutation with clonal loss of heterozygosity of 11p15

- Diffuse hyperinsulinism

- KATP channel disorders

- SUR1 mutations

- Kir6.2 mutations

- Glucokinase gain-of-function mutations

- Hyperammonemic hyperinsulinism (glutamate dehydrogenase gain-of-function mutations)

- Short chain acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency

- Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome (Jaeken's Disease)

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome(suspected due to hyperinsulinism but pathophysiology uncertain: 11p15 mutation or IGF2 excess)

- KATP channel disorders

- Acquired forms of hyperinsulinism

- Insulinomas (insulin-secreting tumors)

- Islet cell adenoma or adenomatosis

- Islet cell carcinoma

- Adult nesidioblastosis

- Autoimmune insulin syndrome

- Noninsulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia

- Reactive hypoglycemia (also see idiopathic postprandial syndrome)

- Gastric dumping syndrome

- Congenital hyperinsulinism

- Drug induced hyperinsulinism

- Sulfonylurea

- Aspirin

- Pentamidine

- Quinine

- Disopyramide

- Bordetella pertussis vaccine or infection

- D-chiro-inositol and myo-inositol[2]

- Hypoglycemia due to exogenous (injected) insulin

- Insulin self-injected for treatment of diabetes (i.e., diabetic hypoglycemia)

- Insulin self-injected surreptitiously (e.g., Munchausen syndrome)

- Insulin self-injected in a suicide attempt or fatality

- Various forms of diagnostic challenge or "tolerance tests"

- Insulin tolerance test for pituitary or adrenergic response assessment

- Protein challenge

- Leucine challenge

- Tolbutamide challenge

- Insulin potentiation therapy

- Insulin-induced coma for depression treatment

Diagnosis

When the cause of hypoglycemia is not obvious, the most valuable diagnostic information is obtained from a blood sample (a "critical specimen") drawn during the hypoglycemia. Detectable amounts of insulin are abnormal and indicate that hyperinsulinism is likely to be the cause. Other aspects of the person's metabolic state, especially low levels of free fatty acids, beta-hydroxybutyrate and ketones, and either high or low levels of C-peptide and proinsulin can provide confirmation.

Clinical features and circumstances can provide other indirect evidence of hyperinsulinism. For instance, babies with neonatal hyperinsulinism are often large for gestational age and may have other features such as enlarged heart and liver. Knowing that someone takes insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents for diabetes obviously makes insulin excess the presumptive cause of any hypoglycemia.

Most sulfonylureas and aspirin can be detected on a blood or urine drug screen tests, but insulin cannot. Endogenous and exogenous insulin can be distinguished by the presence or absence of C-peptide, a by-product of endogenous insulin secretion which is not present in pharmaceutical insulin. Some of the newer analog insulins are not measured by the usual insulin level assays.

Treatment

Acute hypoglycemia is reversed by raising the blood glucose. Glucagon should be injected intramuscularly or intravenously, or dextrose can be infused intravenously to raise the blood glucose. Oral administration of glucose can worsen the outcome, as more insulin is eventually produced. Most people recover fully even from severe hypoglycemia after the blood glucose is restored to normal. Recovery time varies from minutes to hours depending on the severity and duration of the hypoglycemia. Death or permanent brain damage resembling stroke can occur rarely as a result of severe hypoglycemia. See hypoglycemia for more on effects, recovery, and risks.

Further therapy and prevention depends upon the specific cause.

Most hypoglycemia due to excessive insulin occurs in people who take insulin for type 1 diabetes. Management of this hypoglycemia is sugar or starch by mouth (or in severe cases, an injection of glucagon or intravenous dextrose). When the glucose has been restored, recovery is usually complete. Prevention of further episodes consists of maintaining balance between insulin, food, and exercise. Management of hypoglycemia due to treatment of type 2 diabetes is similar, and the dose of the oral hypoglycemic agent may need to be reduced. Reversal and prevention of hypoglycemia is a major aspect of the management of type 1 diabetes.

Hypoglycemia due to drug overdose or effect is supported with extra glucose until the drugs have been metabolized. The drug doses or combination often needs to be altered.

Hypoglycemia due to a tumor of the pancreas or elsewhere is usually curable by surgical removal. Most of these tumors are benign. Streptozotocin is a specific beta cell toxin and has been used to treat insulin-producing pancreatic carcinoma.

Hyperinsulinism due to diffuse overactivity of beta cells, such as in many of the forms of congenital hyperinsulinism, and more rarely in adults, can often be treated with diazoxide or a somatostatin analog called octreotide. Diazoxide is given by mouth, octreotide by injection or continuous subcutaneous pump infusion. When congenital hyperinsulinism is due to focal defects of the insulin-secretion mechanism, surgical removal of that part of the pancreas may cure the problem. In more severe cases of persistent congenital hyperinsulinism unresponsive to drugs, a near-total pancreatectomy may be needed to prevent continuing hypoglycemia. Even after pancreatectomy, continuous glucose may be needed in the form of gastric infusion of formula or dextrose.

High dose glucocorticoid is an older treatment used for presumptive transient hyperinsulinism but incurs side effects with prolonged use.

See also

References

- ↑ Gϋemes, Maria; Rahman, Sofia Asim; Kapoor, Ritika R.; Flanagan, Sarah; Houghton, Jayne A. L.; Misra, Shivani; Oliver, Nick; Dattani, Mehul Tulsidas; Shah, Pratik (1 December 2020). "Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in children and adolescents: Recent advances in understanding of pathophysiology and management". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 21 (4): 577–597. doi:10.1007/s11154-020-09548-7. ISSN 1573-2606. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ Villeneuve, MC; Ostlund RE, Jr; Baillargeon, JP (January 2009). "Hyperinsulinemia is closely related to low urinary clearance of D-chiro-inositol in men with a wide range of insulin sensitivity". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 58 (1): 62–8. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2008.08.007. PMID 19059532.