Anthrax vaccine adsorbed

| |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target | Anthrax |

| Vaccine type | Subunit |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Biothrax |

| Other names | rPA102 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a607013 |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | SQ, IM |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| | |

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) is the only FDA-licensed human anthrax vaccine in the United States. It is produced under the trade name BioThrax by the Emergent BioDefense Corporation (formerly known as BioPort Corporation) in Lansing, Michigan. The parent company of Emergent BioDefense is Emergent BioSolutions of Rockville, Maryland. It is sometimes called MDPH-PA or MDPH-AVA after the former Michigan Department of Public Health (MDPH; succeeded by the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services), which formerly was involved in its production.

AVA originated in studies done in the 1950s and was first licensed for use in humans in 1970. In the US, the principal purchasers of the vaccine are the Department of Defense and Department of Health and Human Services. Ten million courses (60 million doses) of the vaccine have been purchased for the US Strategic National Stockpile in anticipation of the need for mass vaccinations owing to a future bio-terrorist anthrax attack. The product has attracted some controversy owing to alleged adverse events and questions as to whether it is effective against the inhalational form of anthrax.

Description

Antigen

AVA is classified as a subunit vaccine that is cell-free and containing no whole or live anthrax bacteria.[1] The antigen (immunologically active) portions are produced from culture filtrates of a toxigenic, but avirulent, nonencapsulated mutant — known as V770-NP1-R — of the B. anthracis Vollum strain.[2] (The Vollum strain was the same one weaponized by the old U.S. biological warfare program.) As with the Sterne (veterinary) anthrax vaccine strain and the similar British anthrax vaccine (known as AVP), AVA lacks the capsule plasmid pXO2 (required for full virulence) and is composed chiefly of the anthrax protective antigen (PA)[3] with small amounts of edema factor (EF) and lethal factor (LF) that may vary from lot to lot. Other uncharacterized bacterial byproducts are also present. Whether or not the EF and LF contribute to the vaccine's efficacy is not known.[4] AVA has smaller amounts of EF and LF than AVP.[5]

Adjuvant

AVA contains aluminium hydroxide (alhydrogel) to adsorb PA as well as to serve as an adjuvant (immune enhancer).[1] As such it is believed to stimulate humoral, but not cell-mediated, immunity.[6] Each dose of the vaccine contains no more than 0.83 mg aluminum per 0.5 mL dose. (This is near the allowed upper limit of 0.85 mg/dose.[7]) It also contains 0.0025% benzethonium chloride as a preservative and 0.0037% formaldehyde as a stabilizer.[1] The mechanism of action of the adjuvant is not entirely understood.

Potency/immunogenicity

Vaccination of humans with AVA induces an immune response to PA. More than 1/3 of subjects develop detectable anti-PA IgG after a single inoculation; 95% do so after a 2nd injection; and 100% after 3 doses. The peak IgG response occurs after the 4th (6 month) dose. The potency of AVA vaccine lots is routinely determined both by the survival rates of parenterally challenged guinea pigs and their anti-PA antibody titres as measured by an enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA). The shelf-life of AVA is reported to be three years when stored between 2 °C and 8 °C (36 °F and 46 °F) and never frozen.

History

Initial research and development (1954-1970)

The vaccine efficacy of AVA in humans was initially established by Philip S. Brachman of the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) in a controlled study undertaken between 1954 and 1959. The study field sites were four wool-sorting mills in the northeastern United States where employees were sometimes exposed to anthrax spores in the course of their work. Over the five years, 379 vaccinees were compared against 414 unvaccinated control subjects. There were 23 cases among controls (5 of them inhalation anthrax) compared with 3 cases among vaccinated (0 inhalation cases). The vaccine was judged to have a 92.5% vaccine efficacy against all types of anthrax experienced.[8] Subsequently, there were no controlled clinical trials in humans of the efficacy of AVA[9] due to the rarity of the condition (especially in the inhalational form) in humans and the ethical inadmissibility of conducting dangerous challenge studies in human subjects. Supportive animal challenge studies were done, however, showing that unvaccinated animals uniformly die whereas vaccinated animals are protected. About 95% of rhesus monkeys (62 of 65) survived challenge, as did 97% of rabbits (114 of 117). Guinea pigs (which are a poorer model for human anthrax than are monkeys or rabbits) showed a 22% protection (19 of 88).

Licensure and limited occupational use (1970-1991)

In 1970, AVA was first licensed by the USPHS for protection against cutaneous anthrax to a state-owned facility operated by the Michigan Department of Public Health. In 1973, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first published standards for making, using and storing AVA.[10] In the mid-1980s, the FDA approved it specifically for two limited preventive indications: 1) individuals who may come in contact with animal products or high-risk persons such as veterinarians and others handling potentially infected animals; and 2) individuals engaged in diagnostic or investigational activities involving anthrax spores. In 1985, the FDA published a Proposed Rule for a specific product review of the AVA, stating that the vaccine's "efficacy against inhalation anthrax is not well documented" (a statement quoted controversially many years later). For many years, AVA was a little known product considered to be safe for pre-exposure use in the US in at-risk veterinarians, laboratory workers, livestock handlers, and textile plant workers who process animal hair. In 1990, the State of Michigan changed the name of its original production plant facility to the Michigan Biologic Products Institute (MBPI) as it gave up state ownership and converted it to a private entity. The same year (as later revealed) MBPI changed both the fermenters and the filters used in manufacturing AVA without notifying the FDA, thus reportedly causing a 100 fold increase in the PA levels present in vaccine lots.

Only several thousand people had ever received the vaccine up to 1991 when — coincident with Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent Gulf War — MBPI and the U.S. Army entered into an agreement for the manufacture of the vaccine. Later that year, the Army awarded MBPI the Commander's Award for Public Service for their efforts in supplying the US military with increased amounts of AVA for use during the conflict in which the use of anthrax bio-weapons by Iraq had been anticipated.

Initial use in US military (1991-1997)

Use of AVA expanded dramatically in 1991, when the US military, concerned that Iraq possessed anthrax bioweapons, administered it to some 150,000 service members deployed for the Gulf War. Hussein never deployed his bio-weapons, but subsequent confirmation of an Iraqi bioweapons program — including 8,500 liters of concentrated anthrax spores (6,500 liters of it filled into munitions) — came in 1995 and later when the Iraqi government began to fully disclose the scope and scale of the effort, which it had pursued since the 1980s.

Meanwhile, MBPI fell afoul of FDA inspectors and reviewers when it failed inspections (1993, 1997) and received warning letters (1995) and Notices of Intention to Revoke (1997) from the agency. At issue were a failure to validate the AVA manufacturing process to the FDA's satisfaction and various quality control failures, including reuse of expired vaccine, inadequate testing procedures, and use of lots that had failed testing. All of these developments vexed the Army, not only in its efforts to obtain sufficient vaccine for the troops, but in its desire to have AVA validated and fully licensed for prevention of inhalational anthrax, which is the expected weaponized form of the disease (as opposed to the cutaneous form for which the vaccine had been licensed in 1970). In 1995, the Army contracted with the Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) to develop a plan to obtain FDA approval for a license amendment for AVA in order to add inhalational anthrax exposure to the product license thus enabling the manufacturer to list on the product license that the vaccine was effective against that form of the disease. The following year, MBPI submitted an "IND application" to modify the product's license to add an indication for inhalation anthrax, thus formally establishing AVA as an "experimental" vaccine when used to prevent anthrax in the inhalational form.

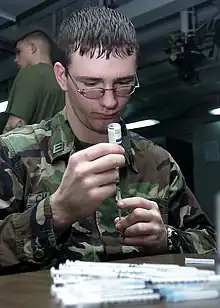

In 1996, the US Department of Defense (DoD) sought and received permission from the FDA to begin vaccinations of all military personnel without obtaining a new licensed indication for AVA. It announced a plan the following year for the mandatory vaccination of all US service members. Under the plan all military personnel, including new recruits, would begin receiving what was then a six-shot series of inoculations in the following fashion: Phase 1: Forces assigned now, or soon rotating, to high threat areas in Southwest Asia and Korea; Phase 2: Early deploying forces into high threat areas; Phase 3: Remainder of the force and new recruits; and Phase 4: Continuation of the program with annual booster shots.

The AVIP and initial mandatory military use (1997-2000)

There were no published studies of AVA's safety in humans[11] until the advent of the Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program (AVIP). This program, initiated by the Clinton administration and announced by Secretary of Defense William Cohen in 1997, made the vaccine mandatory for active duty US service personnel. Vaccinations began in March 1998 with personnel sent to high-risk areas, such as South Korea and Southwest Asia. Also in 1998, MBPI was purchased by BioPort Corporation of Lansing, Michigan (jointly with former MBPI laboratory directors) for approximately $24 million. The same year, a particularly damning FDA report was issued resulting in the temporary suspension of AVA shipments from the production plant. Much controversy ensued due to the FDA infractions, the mandatory nature of the program, and to a public perception that AVA was unsafe — possibly causing sometimes serious side effects — and might be contributing to the highly politically charged malady known as "Gulf War syndrome". Hundreds of service members were compelled to leave the military (some of them court-martialed) for resisting the inoculations during the first six years of the program.

Adverse events following AVA administration were assessed in several studies conducted by the DoD in the context of the routine anthrax vaccination program. Between 1998 and 2000, at U.S. Forces, Korea, data were collected at the time of anthrax vaccination from 4,348 service personnel regarding adverse events experienced from a previous dose of anthrax vaccine. Most reported events were localized, minor, and self-limited. After the first or second dose, 1.9% reported limitations in work performance or had been placed on limited duty. Only 0.3% reported >1 day lost from work; 0.5% consulted a clinic for evaluation; and one person (0.02%) required hospitalization for an injection-site reaction. Adverse events were reported more commonly among women than among men. A second study, also between 1998 and 2000, at Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii, assessed adverse events among 603 military health-care workers. Rates of events that resulted in seeking medical advice or taking time off work were 7.9% after the first dose; 5.1% after the second dose; 3.0% after the third dose; and 3.1% after the fourth dose. Events most commonly reported included muscle or joint aches, headache, and fatigue. However, these studies are subject to several methodological limitations, including sample size, the limited ability to detect adverse events, loss to follow-up, exemption of vaccine recipients with previous adverse events, observational bias, and the absence of unvaccinated control groups.[12]

By 2000, some 425,976 US service members had received 1,620,793 doses of AVA.

The IOM review (2000-2004)

In October 2000, a committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academy of Sciences was asked by the US Congress to review AVA according to the best available evidence. It issued its study in March 2002. The IOM panel noted that human data on inhalational anthrax prevention is limited due to the natural low incidence of disease and that therefore animal model data are the best we are ever likely to have. Primates and rabbits were considered the best models for human disease. As regards vaccine effectiveness, "The committee finds that the available evidence from studies with humans and animals, coupled with reasonable assumptions of analogy, show that AVA as licensed is an effective vaccine for the protection of humans against anthrax, including inhalational anthrax, caused by all known or plausible engineered strains of B. anthracis." With regard to safety, "The committee found no evidence that people face an increased risk of experiencing life-threatening or permanently disabling adverse events immediately after receiving AVA, when compared with the general population. Nor did it find any convincing evidence that people face elevated risk of developing adverse health effects over the longer term, although data are limited in this regard (as they are for all vaccines)." Side effects of AVA were found to be "comparable to those observed with other vaccines regularly administered to adults". The committee concluded that AVA is "safe and efficacious" for pre-exposure prevention of inhalational anthrax. It also asserted that a new and improved anthrax vaccine might have greater assurance of consistency than AVA and recommended licensure of a new vaccine requiring fewer doses and producing fewer local reactions.[13]

In the months after the October 2001 anthrax letters attacks, Washington and New York area mail sorters were advised to receive prophylactic vaccination with AVA. Owing to the controversy surrounding the administration of the vaccine to military personnel, however, some 6,000 US Postal Service employees balked at this, preferring to take their chances with the risks of residual anthrax spores in the workplace.[14]

BioPort changed its name to Emergent BioSolutions in 2004.

Injunctions and FDA re-reviews (2004-2006)

Despite the positive IOM assessment, mandatory vaccinations of military personnel were halted due to an injunction which was put into place on October 27, 2004. The injunction cast questions about numerous substantive challenges regarding the anthrax vaccine in footnote #10,[15] yet the procedural findings centered on FDA procedural issues, stating that additional public comment should have been sought before the FDA issued its Final Rule declaring the vaccine safe and effective on 30 December 2003.[16] The FDA's incomplete rulemaking from 1985 effectively rendered the anthrax vaccine program illegal. The basis was the never finalized FDA Proposed Rule. In that rulemaking the FDA published, but never finalized, a licensing rule for the anthrax vaccine in the Federal Register, which included an expert review panel's findings. Those findings included the fact that the "Anthrax vaccine efficacy against inhalation anthrax is not well documented," and that "No meaningful assessment of its value against inhalation anthrax is possible due to its low incidence," and that "The vaccine manufactured by the Michigan Department of Public Health has not been employed in a controlled field trial."[17]

On December 15, 2005, the FDA re-issued a Final Rule & Order on the license status of the anthrax vaccine.[18] After reviewing the extensive scientific evidence and carefully considering comments from the public, the FDA again determined that the vaccine is appropriately licensed for the prevention of anthrax, regardless of the route of exposure. Also in 2005, the George W. Bush administration established a policy to ensure that the Strategic National Stockpile retains a current unexpired inventory of 60 million doses of AVA. (The US GAO reports that 4 million doses of the inventory will expire every year, requiring vaccine destruction services.) These would be used for pre- or post-exposure vaccination — of emergency first responders (police, firefighters), federal responders, medical practitioners, and private citizens — in the event of a bioterrorist anthrax attack.

Reinstatement of the AVIP (2006-2016)

On October 16, 2006, the DoD announced the reinstatement of mandatory anthrax vaccinations for more than 200,000 troops and defense contractors. (Another lawsuit was filed by the same attorneys as before, challenging the basis of the vaccine's license on scientific grounds.) The reinstated policy required vaccinations for most military units and civilian contractors assigned to homeland bioterrorism defense or deployed in Iraq, Afghanistan or South Korea.[19] A modification of previous policy allowed military personnel no longer deployed to higher threat areas to receive follow up doses and booster shots on a voluntary basis. As of June 2008, over 8 million doses of AVA had been administered to over 2 million US military personnel as part of the AVIP.

In December 2008, the FDA approved the new BioThrax IM formulation for intramuscular injections thus reducing the immunization schedule from a total of 6 shots to 5 shots (see below).

On February 12, 2009, Emergent BioSolutions announced that the Drugs Controller General of India (DGCI) had approved licensing of BioThrax for distribution by Biological E. of Hyderabad.[20]

In 2011, BioThrax was approved for sale in Singapore by the Singapore Health Sciences Authority.[21]

Building 55 approval (2016)

The FDA approved the company's license (officially called a supplemental Biologics License Application, or sBLA) to manufacture BioThrax in a large building in Lansing, Michigan known as "Building 55." According to Homeland Preparedness News, "The use of Building 55 to manufacture BioThrax could expand manufacturing capacity to an estimated 20 to 25 million doses annually."[22]

The US federal government has a goal to stockpile 75 million doses of anthrax vaccines. The new facility and its capacity will help Emergent meet the government's security needs.[22]

Emergent worked with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the United States Department of Health and Human Services on the project. The facility's value is estimated at $104 million, according to Yahoo Finance.[23]

Administration

Vaccination schedule

Vaccination with Emergent BioSolutions BioThrax AVA and BioThrax IM intramuscular injections in the deltoid is given at 0 and 4 weeks, with three vaccinations at 6, 12, and 18 months, followed by annual boosters.

As of 11 December 2008, the new BioThrax IM for intramuscular injections in the deltoid was approved by the US FDA which changes the immunity initialization sequence from 6 to 5 shots given at 0 and 4 weeks and then at 6, 12, and 18 months, followed by annual boosters. This prolonged initialization sequence is required with annual booster shots, because the anthrax vaccine's primary ingredient, the Anthrax Protective Antigen, can impair the life-cycle of the human immune system's memory B-Cells and memory T-cells, through inducing the production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) which sequesters furin.

The loss of memory B-Cells leads to declining concentrations of IgG which can sequester APA, and therefore declining tolerance to the presence of anthrax bacteria. There is the potential that other memory B-Cell populations will be adversely affected as well.

Furin is the protein activator for pro-parathyroid hormone, transforming growth factor beta 1, von Willebrand factor, pro-albumin, pro-beta-secretase, membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase, gonadotropin, and nerve growth factor. Furin is also essential to maintain peripheral immune tolerance by creating memory T-cells and suppressor T-cells.[24]

Based on a retrospective cohort study of female military members inoculated during pregnancy, there may be a small risk of birth defect for inoculation during first trimester. However, the difference between the vaccinated and unvaccinated control groups was not large enough to be conclusive.[25]

The approved US FDA package insert for AVA contains the following notice:

Pregnant women should not be vaccinated against anthrax unless the potential benefits of vaccination have been determined to outweigh the potential risk to the fetus. If this drug is used during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while taking this product, the patient should be apprised of the potential hazard to the fetus.[26]

Contraindications

The approved US FDA package insert for AVA contains the following notice:

- Severe allergic reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis) after a previous dose of BioThrax.

- Administer with caution to patients with a possible history of latex sensitivity because the vial stopper contains dry natural rubber and may cause allergic reactions.[26]

Adverse reactions

There have been no long-term sequelae of the known adverse events (local or systemic reactions) and no pattern of frequently reported serious adverse events for AVA.[12]

The approved FDA package insert for AVA contains the following notice: "The most common (>10%) local (injection-site) adverse reactions observed in clinical studies were tenderness, pain, erythema and arm motion limitation. The most common (>5%) systemic adverse reactions were muscle aches, fatigue and headache." Also, "Serious allergic reactions, including anaphylactic shock, have been observed during post-marketing surveillance in individuals receiving BioThrax".[26]

Drug interactions

The approved US FDA package insert for AVA contains the following notice:

Immunosuppressive therapies may diminish the immune response to BioThrax.[26]

Post-exposure vaccination

Some studies show that use of antibiotics effective against anthrax plus administration of AVA is the most beneficial approach for purposes of post-exposure prophylaxis. This practice has been endorsed by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the Johns Hopkins Working Group on Civilian Biodefense, and the 2002 Institute of Medicine report on the vaccine. However, AVA is not licensed for post-exposure prophylaxis for inhalational anthrax or for use in a 3-dose regimen. Any such use, therefore, would be on an off-label or IND (officially experimental) basis. "... the safety and efficacy of BioThrax for post-exposure setting have not been established.".[26]

Controversy

In the United States

Although many individuals have expressed health concerns after receiving anthrax vaccine, a congressionally directed study by the Institute of Medicine (part of the National Academy of Sciences) concluded that this anthrax vaccine is as safe as other vaccines. The Academy considered more than a dozen studies using various scientific designs, and heard personally from many concerned US military service members.[13]

Development of a replacement vaccine

While effective in protecting against anthrax, the licensed vaccine schedule is not very efficient, involving a cumbersome five (previously six) dose injection series. Typically, five injections are given over a period of 18 months in order to induce a protective immune system response. In addition, in 2004 the US Department of Health and Human Services contracted with Vaxgen Inc. to supply up to 75 million doses of a recombinant anthrax vaccine, for $877 million.[27] To be acceptable to HHS, this vaccine was to be protective against anthrax in three doses or less. On December 19, 2006, HHS voided the contract, because of stability problems with the vaccine, and a failure to start a Phase 2 clinical trial on time.[28] In May 2008, Emergent Biosolutions, the Maryland-based successor to BioPort, both controlled by former Lebanese banker Faud el Hibri, acquired rights to Vaxgen's patents and processes.[29]

On 30 October 2012, the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases agreed to provide $6.5 million to the United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency for initial work on a potential future anthrax vaccine that could be delivered through the nasal passage instead of via a needle. The HPA has long produced the UK's AVP anthrax vaccine.

Research is being continuously done to develop and test new improved candidate anthrax vaccines.[30][31][32] The primary immunogen of acellular existing vaccines, i.e., Protective Antigen (PA), is highly thermolabile due to inherent structural and chemical instability.[33][34][35][36] Various endeavors are underway to thermostabilize PA molecule by solvent engineering and genetic engineering approaches to generate a thermostable anthrax vaccine formulation without compromising on the immunogenicity and its protective potential.[32] The generation of a thermostable anthrax vaccine would minimize the current cold chain requirement for its storage and transport. Anthrax vaccines which would be amenable to other modes of administration such as oral, nasal, skin patch etc., are also being experimented.

Human Genome Sciences announced in 2007, the development of a new anthrax neutralizing monoclonal antibody with the trademark name of 'ABthrax'. The vaccine sensitizes the human immune system to the presence of the Anthrax Toxin Factor. In 2008, HGS reported on testing on 400 human volunteers given ABthrax. In 2009, HGS announced that they had made first delivery of 20,000 doses of ABthrax to the United States Department of Defense.[37] Currently three anthrax antitoxin antibodies, namely, Anthrax immune globulin intravenous or 'AIGIV' (polyclonal), 'Obiltoxaximab' or 'ANTHIM' (monoclonal), and 'Raxibacumab' or 'ABthrax' (monoclonal) are approved for the treatment of inhalation anthrax.[38]

References

- 1 2 3 BioThrax Package Insert

- ↑ Puziss M, Manning LC, Lynch JW, et al. (1963). "Large-scale production of protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis in anaerobic cultures". Appl Microbiol. 11 (4): 330–334. doi:10.1128/AEM.11.4.330-334.1963. PMC 1057997. PMID 13972634.

- ↑ Leppla SH, Klimpel KR, Singh Y, et al (June 1996), "Interaction of anthrax toxin with mammalian cells", Salisbury Medical Bulletin, Special Supplement #87, pg 91.

- ↑ Nass M (March 1999). "Anthrax vaccine. Model of a response to the biologic warfare threat". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 13 (1): 187–208, viii. doi:10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70050-7. PMID 10198799. Archived from the original on 2013-01-09. Retrieved 2012-10-31.

- ↑ Turnbull PC (August 1991). "Anthrax vaccines: past, present and future". Vaccine. 9 (8): 533–9. doi:10.1016/0264-410x(91)90237-z. PMID 1771966.

- ↑ Welkos SL, Friedlander AM (August 1988). "Comparative safety and efficacy against Bacillus anthracis of protective antigen and live vaccines in mice". Microbial Pathogenesis. 5 (2): 127–39. doi:10.1016/0882-4010(88)90015-0. PMID 3148815.

- ↑ Baylor NW, Egan W, Richman P (May 2002). "Aluminum salts in vaccines--US perspective". Vaccine. 20 Suppl 3: S18-23. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00166-4. PMID 12184360.

- ↑ Brachman PS, Gold H, Plotkin SA, Fekety FR, Werrin M, Ingraham NR (April 1962). "Field Evaluation of a Human Anthrax Vaccine". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 52 (4): 632–45. doi:10.2105/ajph.52.4.632. PMC 1522900. PMID 18017912.

- ↑ Brachman PS and Friedlander AM (1994), "Anthrax", In: Plotkin SA and Mortimer EA (eds): Vaccines, 2nd ed.; Philadelphia, WB Saunders, pg 729.

- ↑ 21 CFR Section 620.20.

- ↑ Brachman (1994), Op. cit., pg 729.

- 1 2 Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (April 2000). "Surveillance for adverse events associated with anthrax vaccination--U.S. Department of Defense, 1998-2000". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 49 (16): 341–5. PMID 10817479.

- 1 2 Institute of Medicine (April 2002). The Anthrax Vaccine: Is It Safe? Does It Work?. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10310. ISBN 978-0-309-08309-6. LCCN 2002104241. PMID 25057597. Lay summary (PDF).

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - ↑ Allen, Arthur (2007), Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine's Greatest Lifesaver; W.W. Norton & Co., pp 13-14.

- ↑ "John Doe #1 v. Donald H. Rumsfeld, et al" (PDF). Military Vaccine (MILVAX) Agency. 2004-10-27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Federal Register, 5 Jan 2006, vol 69: pp 255-67.

- ↑ "50 FR 51002 published on Dec. 13, 1985" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ↑ FDA Final Order. Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Issued December 15, 2005.

- ↑ Mandatory Vaccine Article - 'Mandatory Anthrax Shots to Return', Christopher Lee, Washington Post (October 17, 2006)

- ↑ "Emergent BioSolutions Announces That BioThrax (Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed) Receives Market Authorization in India (Press Release)". 12 February 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Clabaugh J (24 June 2011). "Emergent gets entry to Singapore". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- 1 2 "FDA approves sBLA for Biothrax manufacture at Emergent BioSolutions' Building 55". Homeland Preparedness News. 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ↑ "Emergent BioSolutions Receives FDA Approval for Large-Scale Manufacturing of BioThrax in Building 55". Yahoo Finance. 2016-08-15. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ↑ Pesu M, Watford WT, Wei L, Xu L, Fuss I, Strober W, et al. (September 2008). "T-cell-expressed proprotein convertase furin is essential for maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance". Nature. 455 (7210): 246–50. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..246P. doi:10.1038/nature07210. PMC 2758057. PMID 18701887.

- ↑ Ryan MA, Smith TC, Sevick CJ, Honner WK, Loach RA, Moore CA, Erickson JD (August 2008). "Birth defects among infants born to women who received anthrax vaccine in pregnancy". American Journal of Epidemiology. 168 (4): 434–42. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn159. PMID 18599489.

- 1 2 3 4 5 US FDA, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research CBER, Product Approval Information for Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (December 2008)

- ↑ Vaxgen anthrax vaccine contract information. Archived December 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Heavey S (20 December 2006). "U.S. cancels VaxGen anthrax vaccine contract". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ "VaxGen sells anthrax vaccine candidate to Emergent BioSolutions". Forbes Magazine. 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009.

- ↑ Goodman L (October 2004). "Taking the sting out of the anthrax vaccine". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 114 (7): 868–9. doi:10.1172/JCI23259. PMC 518679. PMID 15467819.

- ↑ Friedlander AM, Grabenstein JD, Brachman PS (2013-01-01). "Anthrax vaccines". In Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA (eds.). Vaccines (Sixth ed.). London: W.B. Saunders. pp. 127–140. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-0090-5.00022-7. ISBN 978-1-4557-0090-5.

- 1 2 Manish M, Verma S, Kandari D, Kulshreshtha P, Singh S, Bhatnagar R (August 2020). "Anthrax prevention through vaccine and post-exposure therapy". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 20 (12): 1405–1425. doi:10.1080/14712598.2020.1801626. PMID 32729741. S2CID 220877509.

- ↑ Singh S, Singh A, Aziz MA, Waheed SM, Bhat R, Bhatnagar R (September 2004). "Thermal inactivation of protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis and its prevention by polyol osmolytes". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 322 (3): 1029–37. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.020. PMID 15336568.

- ↑ Powell BS, Enama JT, Ribot WJ, Webster W, Little S, Hoover T, et al. (August 2007). "Multiple asparagine deamidation of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen causes charge isoforms whose complexity correlates with reduced biological activity". Proteins. 68 (2): 458–79. doi:10.1002/prot.21432. PMID 17469195. S2CID 21178350.

- ↑ Singh S, Ahuja N, Chauhan V, Rajasekaran E, Mohsin Waheed S, Bhat R, Bhatnagar R (September 2002). "Gln277 and Phe554 residues are involved in thermal inactivation of protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 296 (5): 1058–62. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02049-1. PMID 12207879.

- ↑ D'Souza AJ, Mar KD, Huang J, Majumdar S, Ford BM, Dyas B, et al. (February 2013). "Rapid deamidation of recombinant protective antigen when adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide gel correlates with reduced potency of vaccine". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 102 (2): 454–61. doi:10.1002/jps.23422. PMID 23242822.

- ↑ BioWatch: HGS shipping anthrax treatment in $150M deal Archived 2011-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Gazette.Net - Maryland Community Newspapers Online

- ↑ Bower WA, Schiffer J, Atmar RL, Keitel WA, Friedlander AM, Liu L, et al. (December 2019). "Use of Anthrax Vaccine in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2019". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 68 (4): 1–14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6804a1. PMC 6918956. PMID 31834290.

Further reading

- Donegan S, Bellamy R, Gamble CL (April 2009). "Vaccines for preventing anthrax". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006403. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006403.pub2. PMC 6532564. PMID 19370633.

- Borio LL (July 2005). "The Second Generation Anthrax Vaccine Candidate: rPA102". Clinicians' Biosecurity News.</ref>

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |

- "Anthrax Vaccine Information Statement". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 8 January 2020.

- "Biothrax". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. STN: BL 103821.

- Anthrax Vaccines at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)