Pentavalent vaccine

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| DTP vaccine | Vaccine |

| Hepatitis B vaccine | Vaccine |

| Haemophilus vaccine | Vaccine |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Quintavax, Pentavac, Pentacel, Pediacel, others |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Routes of use | Intramuscular injection |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| ATC code | |

A pentavalent vaccine, also known as a 5-in-1 vaccine, is a combination vaccine that contains five vaccines to protect against five different infections.[1]

Pentavalent vaccine frequently refers to the 5-in-1 vaccine protecting against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type B,[1][2] which is generally used in middle- and low-income countries, where polio vaccine is given separately.[3][4]

Another pentavalent vaccine is the 5-in-1 vaccine that protects against diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, and Haemophilus influenza type B, which was used in the UK until 2017, following which a 6-in-1 vaccine became available containing the additional protection against hepatitis B.[1]

By 2013, pentavalent vaccines accounted for 100% of the DTP-containing vaccines procured by UNICEF, which supplies vaccines to a large proportion of the world's children.[5]

Safety

During studies and tests, the conjugated liquid DTPw-HepB-Hib vaccine was found to have positive safety when given as a booster to young children who have been given a vaccination course with another pentavalent booster that requires a change in constitution and was also found to be adequately immunogenic.[6]

History

In October 2004, the European Medicines Agency granted marketing approval within the EU to the pentavalent vaccine Quintanrix, manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline.[7] Quintanrix was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer in 2008.[8]

In September 2006, the first pentavalent vaccine formulation received pre-qualification approval from the World Health Organization.[9]

In 2012, UNICEF and the World Health Organization issued and recommended a joint statement to the Immunization Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and other developing nations in separate documents about the use of pentavalent vaccines to protect against five of the leading causes of vaccine-preventable death in children.[10]

By 2013, pentavalent vaccines accounted for 100% of the DTP-containing vaccines procured by UNICEF, which supplies vaccines to a large proportion of the world's children.[5]

In 2014, South Sudan became the last of the 73 GAVI-supported countries to introduce the five-in-one vaccine.[11]

Society and culture

In May 2010, Crucell N.V. announced a US$110 million award from UNICEF to supply its pentavalent pediatric vaccine Quinvaxem to the developing world.[12]

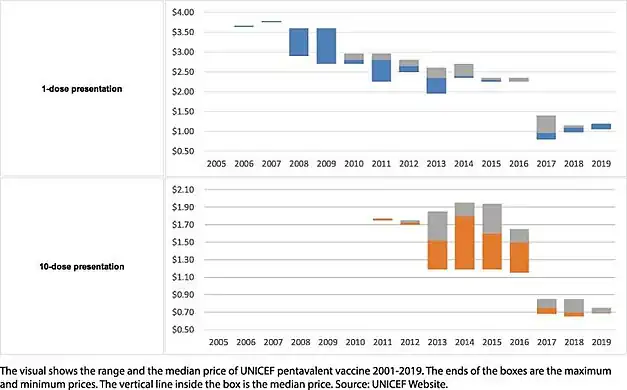

In November 2010, the public-private consortium GAVI announced that the cost of the pentavalent vaccine for emerging-market countries had dropped below $3.00 USD per dose.[13]

High-income countries tend to use alternative formulations using acellular pertussis (Pa), which has a more favourable profile of side-effects, rather than whole-cell pertussis components.[14][1] In Europe, hexavalent vaccines that also contain inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) are in wide use.[15] In the USA, the two pentavalent vaccines that have received marketing approval contain IPV rather than hepatitis B vaccine (DTaP-IPV/Hib vaccine) or Hib vaccine (DTaP-IPV-HepB vaccine).[16]

The number of manufacturers making certified pentavalent vaccine.[17]

The number of manufacturers making certified pentavalent vaccine.[17] All pentavalent vaccine prices fell and price discrimination almost vanished. Graph by GAVI; non-UNICEF prices not shown[17]

All pentavalent vaccine prices fell and price discrimination almost vanished. Graph by GAVI; non-UNICEF prices not shown[17]

India

In 2013, it was found that Pentavac PFS vaccines were being supplied with two different sets of packaging: One set with manufacturing and expiry dates was being provided to private hospitals, whereas the other set without manufacturing and expiry dates was being distributed to government hospitals.[18] It was later clarified that the undated vaccines were supplied by UNICEF and complied with Indian Law.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka introduced Quinvaxem in January 2008. Within three months, four reports of deaths and 24 reports of suspected hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes prompted regulatory attention and precautionary suspension of the initial vaccine lot. A subsequent death that occurred with the next lot in April 2009 led the authorities to suspend pentavalent vaccine use and resume DTwP and hepatitis B vaccination. Following an investigation by independent national and international experts, the vaccine was reintroduced in 2010.[19]

Bhutan

Bhutan introduced Easyfive-TT in September 2009. The identification of five cases with encephalopathy and/or meningoencephalitis shortly after pentavalent vaccination prompted the authorities to suspend vaccination on 23 October 2009. Subsequently, four additional serious cases related to vaccine administered prior to suspension were identified and investigated. After a comprehensive review by independent national and international experts, the vaccine was reintroduced in 2011.[19]

Vietnam

Between December 2012 and March 2013 nine deaths were reported in Viet Nam of children who had recently received injections of the pentavalent vaccine Quinvaxem.[20] On 4 May 2013, the Ministry of Health of Viet Nam announced that use of Quinvaxem was suspended.[21]

After a review of the cases conducted by national experts together with staff from WHO and UNICEF and an independent clinician, no link with vaccination could be identified.[20] The fatalities reported in Viet Nam were attributed to coincidental health problems related in time but not related to the use of Quinvaxem, or cases for which the information available did not allow for a definite conclusion but there were no clinical signs that were consistent with the use of the vaccine. The WHO report emphasized that more than 400 million doses of Quinvaxem had been administered and that no fatal adverse event had ever been associated with Quinvaxem or similar vaccines.[21]

Following additional reports from India, Sri Lanka, and Bhutan of a small number of serious adverse events following immunization with pentavalent vaccines, the WHO asked a global panel of independent experts to review the safety of the vaccine. This review took place 12-13 June 2013 and concluded that no unusual reaction could be attributed to pentavalent vaccines.[22] On 20 June 2013, the Ministry of Health announced that Viet Nam would resume use of Quinvaxem.[19]

The reported events in these Asian nations caused public uncertainty regarding the use of pentavalent vaccines to spread to other developing nations.[23] In response to this, and a corresponding spread of inaccurate information about vaccine safety, the Indian Academy of Pediatrics released a statement in support of pentavalent vaccines.[24]

Formulations

Common versions of pentavalent vaccines include Quinvaxem, Pentavac PFS, Easyfive TT, ComBE Five, Shan5, and Pentabio.[25][26]

| Vaccine | Manufacturer | Date pre-qualified by WHO[9] |

|---|---|---|

| Quinvaxem | Crucell [lower-alpha 1] | 26 September 2006 |

| Pentavac PFS | Serum Institute of India | 23 June 2010 |

| Easyfive TT | Panacea Biotec | 2 October 2013[lower-alpha 2] |

| ComBE Five | Biological E. Limited | 1 September 2011 |

| Shan5 | Shantha Biotechnics | 29 April 2014 |

| Pentabio | Bio Farma | 19 December 2014 |

Notes

- ↑ The vaccine was developed and manufactured by Crucell in Korea and co-produced by Chiron Corporation (later purchased by Novartis International AG on April 20, 2006), which provides four out of the five vaccine elements in bulk.[27][28]

- ↑ Easyfive was removed from the WHO's list of pre-approved and prequalified vaccines in mid-2011.[29] It was re-approved by WHO on 2 October 2013.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "5-in-1 Vaccine (also called Pentavalent Vaccine)". Vaccine Knowledge Project. 22 March 2018. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "Pentavalent vaccine support". www.gavi.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ Organization, World Health; Biologicals, World Health Organization Department of Immunization, Vaccines and (2004). Immunization in Practice: A Practical Guide for Health Staff. World Health Organization. p. 20. ISBN 9789241546515. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ Malhame M, Baker E, Gandhi G, Jones A, Kalpaxis P, Iqbal R, et al. (August 2019). "Shaping markets to benefit global health - A 15-year history and lessons learned from the pentavalent vaccine market". Vaccine. 2: 100033. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100033. PMC 6668221. PMID 31384748.

- 1 2 "Diphtheria Tetanus and Pertussis Vaccine Supply Update" (PDF). UNICEF. October 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ↑ Suárez E, Asturias EJ, Hilbert AK, Herzog C, Aeberhard U, Spyr C (February 2010). "A fully liquid DTPw-HepB-Hib combination vaccine for booster vaccination of toddlers in El Salvador". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 27 (2): 117–24. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892010000200005. PMID 20339615.

- ↑ "Quintanrix : EPAR - Summary for the public" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ "Public statement on Quintanrix: Withdrawal of the marketing authorisation in the European Union". European Medicines Agency. 29 August 2008. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "WHO Prequalified Vaccines". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ↑ "Pentavalent Vaccine" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "With GAVI support, pentavalent vaccine is available in the 73 poorest countries". GAVI Alliance. Archived from the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "Crucell Announces New Award of $110 Million..." PRNewswire (Press release). Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "Price of life-saving vaccine expected to drop significantly in 2011". GAVI. 26 November 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "Vaccine Market". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ↑ Obando-Pacheco P, Rivero-Calle I, Gómez-Rial J, Rodríguez-Tenreiro Sánchez C, Martinón-Torres F (August 2018). "New perspectives for hexavalent vaccines". Vaccine. 36 (36): 5485–5494. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.063. PMID 28676382.

- ↑ "Vaccines Licensed for Use in the United States". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- 1 2 Malhame M, Baker E, Gandhi G, Jones A, Kalpaxis P, Iqbal R, et al. (August 2019). "Shaping markets to benefit global health - A 15-year history and lessons learned from the pentavalent vaccine market". Vaccine. 2: 100033. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2019.100033. PMC 6668221. PMID 31384748.

- ↑ Rajiv G (13 December 2013). "Pentavalent vaccine maker claims Unicef exemption on manufacturing dates". Times Of India. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Update on quality and safety of Quinvaxem (DTwP-HepB-Hib) pentavalent vaccine". World Health Organization. 5 July 2013. Archived from the original on August 30, 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Quinvaxem vaccine" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Safety of Quinvaxem (DTwP-HepB-Hib) pentavalent vaccine". World Health Organization. 10 May 2013. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ "Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, report of meeting held 12-13 June 2013". World Health Organization. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on December 22, 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Datta PT (22 September 2013). "Infant deaths cast shadow on scale-up of pentavalent vaccine use". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Express News Service (13 September 2013). "Pentavalent vaccine is safe, assures IAP". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ "Products". Vaccine World. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "'Shan5' vaccine gets WHO nod". Business Standard. 2014-05-05. Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "Crucell's Quinvaxem gets WHO prequalification". The Pharma Letter. Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "Crucell Announces Product Approval in Korea for Quinvaxem Vaccine". Marketwired. Archived from the original on 2018-06-29. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ↑ "Pentavalent vaccine, Easyfive, removed from WHO list of prequalified vaccines". WHO. Archived from the original on August 12, 2013.

Further reading

- Dodoo AN, Renner L, van Grootheest AC, Labadie J, Antwi-Agyei KO, Hayibor S, et al. (2007). "Safety monitoring of a new pentavalent vaccine in the expanded programme on immunisation in Ghana". Drug Safety. 30 (4): 347–56. doi:10.2165/00002018-200730040-00007. PMID 17408311. S2CID 37633844.

- Verma R, Khanna P, Chawla S (July 2013). "Pentavalent DTP vaccine: need to be incorporated in the vaccination program of India". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 9 (7): 1497–9. doi:10.4161/hv.24382. PMID 23571225.

External links

- Quinn B (6 June 2011). "Drugs companies to lower price of vaccines in developing countries". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Dhar A (2013-10-11). "Pentavalent vaccine gets clean chit, set for national scale-up". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- Sinha V (June 10, 2011). "Health Organization, Gates Foundation Promote Greater Use of Vaccines". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.