Baylisascaris

| Baylisascaris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Baylisascaris procyonis larvae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Nematoda |

| Class: | Chromadorea |

| Order: | Ascaridida |

| Family: | Ascarididae |

| Genus: | Baylisascaris Sprent, 1968[1] |

Baylisascaris is a genus of roundworms that infect more than fifty animal species.

Life cycle

Baylisascaris eggs are passed in feces and become active within a month. They can remain viable in the environment for years, withstanding heat and cold.[2] Animals become infested either by swallowing the eggs or eating another animal infested with Baylisascaris.[2]

Baylisascaris species

Each Baylisascaris species has a host species that it uses to reproduce. The eggs appear in the host species' feces. They can then be ingested by, and infest, a variety of other animals (including humans) that serve as paratenic hosts.

Baylisascaris species include:

- Baylisascaris procyonis (of raccoons)[3]

- Baylisascaris melis (of European badgers)

- Baylisascaris transfuga (of bears)

- Baylisascaris columnaris (of skunks and American badgers)

- Baylisascaris devosi (of fishers and martens)

- Baylisascaris laevis (of marmots)

- Baylisascaris schroederi (of giant pandas)

- Baylisascaris potosis (of kinkajous)[4]

Baylisascaris procyonis

Baylisascaris procyonis is found in the intestines of raccoons in North America, Japan and Germany. It infests 68 to 82% of some raccoon populations, according to the House Rabbit Society.[5] According to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, nearly 100 percent of raccoons in the Midwestern US are infected. This parasite can be extremely harmful or deadly to humans.[6]

Baylisascaris columnaris

Skunks carry Baylisascaris columnaris, a similar species to B. procyonis. Many pet skunks have died from this parasite. According to several skunk experts, many baby skunks from skunk farms have B. columnaris present in their bodies.[7] The exact proportion of skunks that are infested is unknown. Since the worms are often at too early a stage in development to begin shedding eggs into the feces, a fecal test may not detect the parasite, and the pet should be pre-emptively treated with dewormers antiparasitacides.

Baylisascaris eggs are highly resistant to decontamination procedures because of their dense shell and sticky surface. They can survive hot or freezing weather and certain chemicals, remaining viable for several years. Bleach can prevent the eggs from sticking, but will not ensure destruction. According to Parasitism in Companion Animals by Olympic Veterinary Hospital, hand washing is an important countermeasure against ingestion, and decontamination of other surfaces is accomplished by thoroughly flaming with a propane torch or treating with lye.[8] Other forms of high heat such as boiling water or steam will accomplish the same result. Children are more likely to be infected than adults because of their tendency towards pica, particularly geophagy. In spite of the numerous raccoons living in close contact with humans, less than 30 serious infections of humans by Baylisascaris had been reported by 2012; but it is thought that some cases are misdiagnosed as other infections or are never identified.

Disease

Human infection

- Skin irritations from larvae migrating within the skin.

- Respiratory discomfort, liver enlargement, and fever due to reaction to larvae migration.

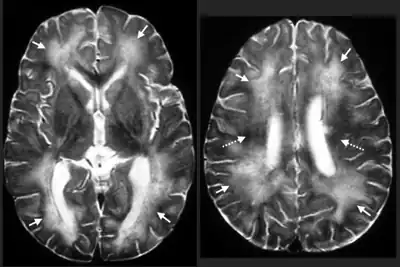

- Eye and brain tissue damage due to the random migration of the larvae.

- Nausea, a lethargic feeling, incoordination and loss of eyesight.

- Severe neurological signs including imbalance, circling and abnormal behavior, caused by extensive tissue damage due to larval migration through the brain, eventually seizures and coma.

Treatment

While deworming can rid the intestine of adult Baylisascaris, no treatment has been shown to alleviate illness caused by migrating larvae.[6] Despite lack of larvicidal effects, albendazole (20–40 mg/kg/d for 1–4 weeks) has been used to treat many cases.[9]

Animals

After an animal swallows the eggs, the microscopic larvae hatch in the intestine and invade the intestinal wall. If they are in their definitive host they develop for several weeks, then enter the intestinal lumen, mature, mate, and produce eggs, which are carried out in the fecal stream. If the larvae are in a paratenic host, they break into the bloodstream and enter various organs, particularly the central nervous system. A great deal of damage occurs wherever the larva try to make a home. In response to the attack, the body attempts to destroy it by walling it off or killing it. The larva moves rapidly to escape, seeking out the liver, eyes, spinal cord or brain. Occasionally they can be found in the heart, lungs, and other organs. Eventually the larva dies and is reabsorbed by the body. In very small species such as mice, it might take only one or two larvae in the brain to be fatal. If the larva does not cause significant damage in vital organs, then the victim will show no signs of disease. On the other hand, if it causes behavioral changes by destroying parts of the brain, the host becomes easier prey, bringing the larva into the intestine of a new host.

See also

References

- ↑ IRMNG (2018). "Baylisascaris Sprent, 1968". Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- 1 2 Ferris, Howard (3 August 2020). "Baylisascaris procyonis". nemaplex.ucdavis.edu. University of California. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2021.

- ↑ Yeitz JL, Gillin CM, Bildfell RJ, Debess EE (January 2009). "Prevalence of Baylisascaris procyonis in raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Portland, Oregon, USA". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 45 (1): 14–8. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-45.1.14. PMID 19204331.

- ↑ Tokiwa, T; Nakamura, S; Taira, K; Une, Y (2014). "Baylisascaris potosis n. sp., a new ascarid nematode isolated from captive kinkajou, Potos flavus, from the Cooperative Republic of Guyana". Parasitology International. 63 (4): 591–6. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2014.03.003. PMID 24662055.

- ↑ Baylisascaris procyonis Article Archived December 5, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Gavin PJ, Kazacos KR, Shulman ST (2005). "Baylisascariasis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (4): 703–18. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.4.703-718.2005. PMC 1265913. PMID 16223954.

- ↑ "Information on Parasites in Skunks". Archived from the original on 2006-02-20.

- ↑ "www.olympicvet.com". Archived from the original on 2005-09-29. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Gaensbauer, James; Levin, Myron J. (2020). "Infections: Parasitic & Mycotic". Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Pediatrics (25th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. Archived from the original on 2023-02-08. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

External links

- Old Rabbit Paralysis Part III: Baylisascaris Procyonis House Rabbit Society

- Baylisascaris procyonis in Dogs Archived 2005-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, D. D. Bowman, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Mar. 11, 2000.

- Information on Parasites in Skunks by Matt Bolek, Diagnostic Parasitologist (link via InternetArchive, as original page no longer valid).

- Parasitism in Companion Animals by Olympic Veterinary Hospital.

- Baylisascaris procyonis: An Emerging Helminthic Zoonosis Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine, Centers for Disease Control.

- Baylisascaris at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)