Fasciolopsis

| Fasciolopsis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fasciolopsis buski egg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Trematoda |

| Order: | Plagiorchiida |

| Family: | Fasciolidae |

| Genus: | Fasciolopsis Looss, 1899 |

| Species: | F. buski |

| Binomial name | |

| Fasciolopsis buski Morakote & Yano, 1990 | |

Fasciolopsis (/ˌfæsioʊˈlɒpsɪs, fəˌsaɪ-/[1][2]) is a genus of trematodes. They are also known as giant intestinal flukes.

Only one species is recognised: Fasciolopsis buski. It is a notable parasite of medical importance in humans and veterinary importance in pigs. It is prevalent in Southern and Eastern Asia. The term for infestation with Fasciolopsis is fasciolopsiasis.

Fasciolopsis buski

Fasciolopsis buski is commonly called the giant intestinal fluke, because it is an exceptionally large parasitic fluke, and the largest known to parasitise humans. Its size is variable and a mature specimen might be as little as 2 cm long, but the body may grow to a length of 7.5 cm and a width of 2.5 cm. It is a common parasite of humans and pigs and is most prevalent in Southern and Southeastern Asia. It is a member of the family Fasciolidae in the order Plagiorchiida. The Echinostomida are members of the class Trematoda, the flukes. The fluke differs from most species that parasitise large mammals, in that they inhabit the gut rather than the liver as Fasciola species do. Fasciolopsis buski generally occupies the upper region of the small intestine, but in heavy infestations can also be found in the stomach and lower regions of the intestine. Fasciolopsis buski is the cause of the pathological condition fasciolopsiasis.[3]

In London, George Busk first described Fasciolopsis buski in 1843 after finding it in the duodenum of a sailor. After years of careful study and self experimentation, in 1925, Claude Heman Barlow determined its life cycle in humans.[4][5][6]

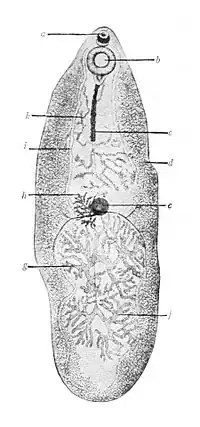

Morphology

Fasciolopsis buski is a large, dorsoventrally flattened fluke characterized by a blunt anterior end, undulating, unbranched ceca (sac-like cavities with single openings), tandem dendritic testes, branched ovaries, and ventral suckers to attach itself to the host. The acetabulum is larger than the oral sucker. The fluke has extensive vitelline follicles. It can be distinguished from other fasciolids by a lack of cephalic cone or "shoulders" and the unbranched ceca.

Life cycle

Adults produce over 25,000 eggs every day; these take up to seven weeks to mature and hatch at 27–32 °C. Immature, unembryonated eggs are discharged into the intestine and stool. In two weeks, eggs become embryonated in water, and after about seven weeks, tiny parasitic organisms called miracidia hatch from the eggs, which then go on to invade a suitable snail intermediate host. Several species in the genera Segmentina and Hippeutis serve as intermediate hosts. In the snail the parasite undergoes several developmental stages (sporocysts, rediae, and cercariae). The cercariae are released from the snail and encyst as metacercariae on aquatic plants such as water chestnut, water caltrop, lotus, bamboo, and other edible plants. The mammalian final host becomes infected by ingesting metacercariae on the aquatic plants. After ingestion, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum in about three months and attach to the intestinal wall. There they develop into adults (20 to 75 mm by 8 to 20 mm) in approximately three months, remaining attached to the intestinal wall of the mammalian hosts (humans and pigs). The adults have a life span of about one year.[7]

Fasciolopsiasis

In infected individuals abdominal pain and diarrhea may occur; asymptomatic individuals are common. The diagnosis is done via a stool sample and the medication that is recommended is called praziquantel[8]

References

- ↑ "Fasciolopsis". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ "Fasciolopsis". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Roberts LS, Janovy, J, Jr. (2009). "Foundations of Parasitology." McGraw Hill, New York, USA, pp. 272–273. ISBN 0-07-302827-4

- ↑ Barlow, Claude Heman (1921). "Experimental Ingestion of the Ova of Fasciolopsis buski; Also the Ingestion of Adult Fasciolopsis buski for the Purpose of Artificial Infestation". The Journal of Parasitology. 8 (1): 40–44. doi:10.2307/3270940. JSTOR 3270940.

- ↑ Dr. Claude Heman Barlow Archived 2017-12-13 at the Wayback Machine. Barlowgenealogy.com. Retrieved on 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Barlow, Claude Heman (1925). "The Life Cycle of the Human Intestinal Fluke Fasciolopsis Buski (Lankester)". American Journal of Hygiene: 98. Archived from the original on 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ↑ Nakagawa, K. (1922). "The development of Fasciolopsis buski Lankester". J Parasitol. 8 (4): 161–166. doi:10.2307/3271232. JSTOR 3271232. Archived from the original on 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ↑ "CDC - Fasciolopsiasis - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)". www.cdc.gov. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

Further reading

- Fasciolopsiasis in children: Clinical,Sociodemographic Profile and outcome. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology2017 vol 35, issue 4 page 551-554 DOI:10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_17_7

External links

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- North-Eastern Hill University Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- BioLib Archived 2018-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- The Taxonomicon Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Atlas of Medical Parasitology

- ZipcodeZoo Archived 2012-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Parasites in Humans Archived 2010-08-11 at the Wayback Machine