Angiostrongyliasis

| Angiostrongyliasis | |

|---|---|

| |

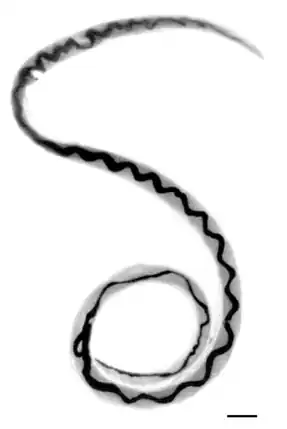

| Adult female worm of Angiostrongylus cantonensis | |

| Symptoms | Severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weakness |

| Causes | Angiostrongylus cantonensis |

| Diagnostic method | Lumbar puncture, brain imaging |

| Prevention | Limiting contact with infected vectors |

| Treatment | Antiparasitic drug |

Angiostrongyliasis is an infection by a roundworm of the Angiostrongylus type. Symptoms may vary from none, to mild, to meningitis.[1]Infection with Angiostrongylus cantonensis (rat lungworm) can occur after ingestion of raw or undercooked snails or slugs, and less likely unwashed fruits and vegetables.[2][3][4]

In humans, A. cantonensis is the most common cause of eosinophilic meningitis or meningoencephalitis.[5] Frequently the infection will resolve without treatment or serious consequences, but in cases with a heavy load of parasites the infection can be so severe it can cause permanent damage to the central nervous system or death.[6][4]

Symptoms and signs

Infection first presents with severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weakness, which gradually lessens and progresses to fever, and then to central nervous system symptoms and severe headache.[2][7]

CNS infection

CNS symptoms begin with mild cognitive impairment and slowed reactions, and in a very severe form often progress to unconsciousness.[8] Patients may present with neuropathic pain early in the infection. Eventually, severe infection will lead to ascending weakness, quadriparesis, areflexia, respiratory failure, and muscle atrophy, and will lead to death if not treated. Occasionally patients present with cranial nerve palsies, usually in nerves 7 and 8, and rarely larvae will enter ocular structures.[9] Even with treatment, damage to the CNS may be permanent and result in a variety of negative outcomes depending on the location of the infection, and the patient may experience chronic pain as a result of infection.[8]

Eye invasion

Symptoms of eye invasion include visual impairment, pain, keratitis, and retinal edema. Worms usually appear in the anterior chamber and vitreous and can sometimes be removed surgically.[2][10][11]

Incubation period

The incubation period in humans is usually from 1 week to 1 month after infection, and can be as long as 47 days.[9] This interval varies, since humans are accidental hosts and the life cycle does not continue predictably as it would in a rat.[6]

Cause

Transmission

Transmission of the parasite is usually from eating raw or undercooked snails or other vectors. Infection is also frequent from ingestion of contaminated water or unwashed salad that may contain small snails and slugs, or have been contaminated by them.[2][12]

Reservoirs

Rats are the definitive host and the main reservoir for A. cantonensis, though other small mammals may also become infected. While Angiostrongylus can infect humans, humans do not act as reservoirs since the worm cannot reproduce in humans and therefore humans cannot contribute to their life cycle.[6]

Vectors

Angiostrongylus cantonensis has many vectors among invertebrates, with the most common being several species of snails, including the giant African land snail (Achatina) in the Pacific islands and apple snails of the genus Pila in Thailand and Malaysia. The golden apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata, is the most important vector in areas of China.[8] Freshwater prawns, crabs, or other paratenic, or transport, hosts can also act as vectors.[6]

Organism

Morphology

A. cantonensis is a nematode roundworm with 3 outer protective collagen layers, and a simple stomal opening or mouth with no lips or buccal cavity leading to a fully developed gastrointestinal tract.[5][2] Males have a small copulatory bursa at the posterior. Females have a "barber pole" shape down the middle of the body, which is created by the twisting together of the intestine and uterine tubules. The worms are long and slender - males are 15.9–19 mm in length, and females are 21–25 mm in length.[13]

Life cycle

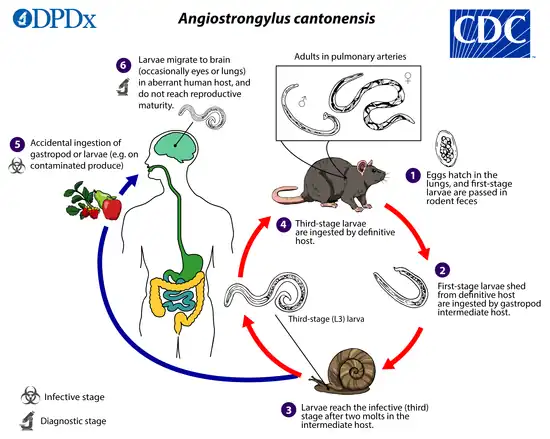

The adult form of A. cantonensis resides in the pulmonary arteries of rodents, where it reproduces. After the eggs hatch in the arteries, larvae migrate up the pharynx and are then swallowed again by the rodent and passed in the stool. These first stage larvae then penetrate or are swallowed by snail intermediate hosts, where they transform into second stage larvae and then into third stage infective larvae. Humans and rats acquire the infection when they ingest contaminated snails or paratenic (transport) hosts including prawns, crabs, and frogs, or raw vegetables containing material from these intermediate and paratenic hosts. After passing through the gastrointestinal tract, the worms enter circulation.[9] In rats, the larvae then migrate to the meninges and develop for about a month before migrating to the pulmonary arteries, where they fully develop into adults.[6]

Humans are incidental hosts; the larvae cannot reproduce in humans and therefore humans do not contribute to the A. cantonensis life cycle. In humans, the circulating larvae migrate to the meninges, but do not move on to the lungs. Sometimes the larvae will develop into the adult form in the brain and CSF, but they quickly die, inciting the inflammatory reaction that causes symptoms of infection.[6]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Angiostrongyliasis is complicated due to the difficulty of presenting the angiostrongylus larvae themselves, and will usually be made based on the presence of eosinophilic meningitis and history of exposure to snail hosts. Eosinophilic meningitis is generally characterized as a meningitis with >10 eosinophils/μL in the CSF or at least 10% eosinophils in the total CSF leukocyte count.[9] Occasionally worms found in the cerebrospinal fluid can be identified in order to diagnose Angiostrongyliasis.[14]

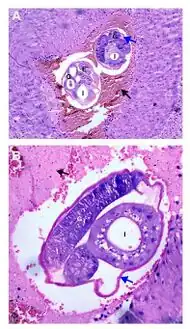

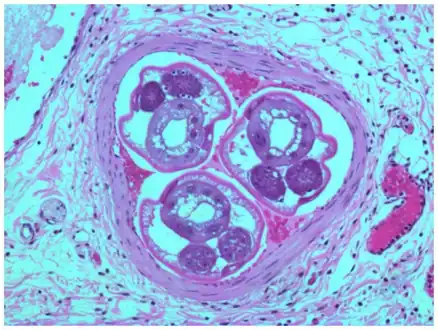

a,b)Adult female worms cross-sectioned at different levels are observed

a,b)Adult female worms cross-sectioned at different levels are observed Angiostrongylus cantonensis lesions in brain

Angiostrongylus cantonensis lesions in brain Angiostrongylus costaricensis inside mensenteric artery

Angiostrongylus costaricensis inside mensenteric artery.jpg.webp) Lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture

Lumbar puncture should always be done in cases of suspected meningitis. In cases of eosinophilc meningitis it will rarely produce worms even when they are present in the CSF, because they tend to cling to the end of nerves. Larvae are present in the CSF in only 1.9-10% of cases.[8] However, as a case of eosinophilic meningitis progresses, intracranial pressure and eosinophil counts should rise. Increased levels of eosinophils in the CSF is a hallmark of the eosinophilic meningitis.[8][15]

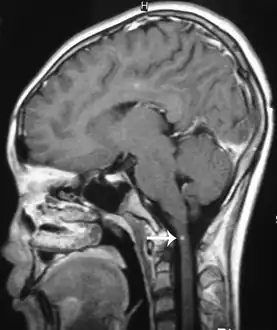

Brain image

Brain lesions, with invasion of brain matter, can be seen on a CT or MRI; however MRI findings may be inconclusive. Sometimes a hemorrhage, probably produced by migrating worms, is present and of diagnostic value.[2][11]

Serology

In patients with elevated eosinophils, serology can be used to confirm a diagnosis of angiostrongyliasis rather than infection with another parasite.[5] There are a number of immunoassays that can aid in diagnosis, however serologic testing is available in few labs in the endemic area, and is frequently too non-specific.[2][15]

The most definitive diagnosis always arises from the identification of larvae found in the CSF or eye, however due to this rarity a clinical diagnosis based on the above tests is most likely.[16]

Prevention

There are public health strategies that can limit the transmission of A. cantonensis by limiting contact with infected vectors. Vector control may be possible, but has not been very successful in the past. Education to prevent the introduction of rats or snail vectors outside endemic areas is important to limit the spread of the disease.[17]

Recommendations

To avoid infection when in endemic areas, travelers should:[18]

- Avoid consumption of uncooked vectors, such as snails and freshwater prawns

- Avoid drinking water from open sources, which may have been contaminated by vectors

Treatment

Treatment of angiostrongyliasis is not well defined, but most strategies include a combination of anti-parasitics to kill the worms, steroids to limit inflammation as the worms die, and pain medication to manage the symptoms of meningitis.[19][20]

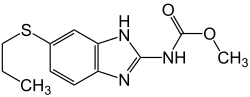

Anthelmintics

Anthelmintics are often used to kill off the worms, however in some cases this may cause patients to worsen due to toxins released by the dying worms. Albendazole, ivermectin, mebendazole, and pyrantel are all commonly used, though albendazole is usually the drug of choice. Studies have shown that anthelmintic drugs may shorten the course of the disease and relieve symptoms. Therefore, anthelmintics are generally recommended, but should be administered gradually so as to limit the inflammatory reaction.[8]

Anti-inflammatories

Anthelmintics should generally be paired with corticosteroids in severe infections to limit the inflammatory reaction to the dying parasites. Studies suggest that a two-week regimen of a combination of mebendazole and prednisolone significantly shortened the course of the disease and length of associated headaches without observed harmful side effects.[21] Other studies suggest that albendazole may be more favorable, because it may be less like to incite an inflammatory reaction.[22][23]

Symptomatic treatment

Symptomatic treatment is indicated for symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headache, and in some cases, chronic pain due to muscle atrophy.[19][2]

Epidemiology

.svg.png.webp)

A. cantonensis and its vectors are endemic to Southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin.[5][24] The infection is becoming increasingly important as globalization allows it to spread to more locations, and as more travelers encounter the parasites. The parasites probably travel effectively through rats traveling (as stowaways) on ships, and through the introduction of snail vectors outside endemic areas.[25][2]

Although mostly found in Asia and the Pacific where asymptomatic infection can be a high percentage, human cases have been reported in the Caribbean, where a lower percentage of the population may be infected. In the United States, cases have been reported in Hawaii, which is in the endemic area. The infection is now endemic in wildlife and a few human cases have also been reported in areas where the parasite was not originally endemic, such as New Orleans and Egypt.[26][5][27]

The disease has also arrived in Brazil, where there were 34 confirmed cases from 2006 to 2014, including one death.[28] The giant African land snail, which can be a vector of the parasite, has been introduced to Brazil as an invasive species and is spreading the disease. There may be more undiagnosed cases, as Brazilian physicians are not familiar with the eosinophilic meningitis associated to angiostrongyliasis and misdiagnose it as bacterial or viral.[28]The parasite is rarely seen outside of endemic areas, and in these cases the individual(s) generally have a history of travel to an endemic area.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Liu, EW; Schwartz, BS; Hysmith, ND; DeVincenzo, JP; Larson, DT; Maves, RC; Palazzi, DL; Meyer, C; Custodio, HT; Braza, MM; Al Hammoud, R; Rao, S; Qvarnstrom, Y; Yabsley, MJ; Bradbury, RS; Montgomery, SP (3 August 2018). "Rat Lungworm Infection Associated with Central Nervous System Disease - Eight U.S. States, January 2011-January 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (30): 825–828. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6730a4. PMC 6072054. PMID 30070981.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sohal, Raman J.; Gilotra, Tarvinder S.; Lui, Forshing (2022). "Angiostrongylus Cantonensis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32310527. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ "Angiostrongyliasis - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- 1 2 Wang, Qiao-Ping; Lai, De-Hua; Zhu, Xing-Quan; Chen, Xiao-Guang; Lun, Zhao-Rong (October 2008). "Human angiostrongyliasis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 8 (10): 621–630. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70229-9. ISSN 1473-3099. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baheti NN; Sreedharan M; et al. (2008). "Eosinophilic meningitis and an ocular worm in a patient from Kerala, south India". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 79 (271): 271. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.122093. PMID 18281446. S2CID 207001013. Archived from the original on 2019-04-24. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 David, John T. and Petri, William A Jr. Markell and Voge's Medical Parasitology. St. Louis, MO: El Sevier, 2006.

- ↑ "Angiostrongyliasis (Concept Id: C0392662) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hua Li; Feng Xu; Jin-Bao Gu & Xiao-Guang Chen (2008). "Case Report: A Severe Eosinophilic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Infection of Angiostrongylus cantonensis". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 79 (4): 568–570. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2008.79.568. PMID 18840746. S2CID 2094357.

- 1 2 3 4 L. Ramirez-Avila (2009). "Eosinophilic Meningitis due to Angiostrongylus and Gnathostoma Species". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (3): 322–327. doi:10.1086/595852. PMID 19123863. S2CID 6773178.

- ↑ Diao, Zongli; Wang, Jing; Qi, Haiyu; Li, Xiaoli; Zheng, Xiaoyan; Yin, Chenghong (April 2011). "Human ocular angiostrongyliasis: a literature review". Tropical Doctor. 41 (2): 76–78. doi:10.1258/td.2010.100294. ISSN 1758-1133. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- 1 2 Martins, Yuri C.; Tanowitz, Herbert B.; Kazacos, Kevin R. (January 2015). "Central nervous system manifestations of Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection". Acta Tropica. 141: 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.10.002. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ↑ Cowie, RH (June 2013). "Pathways for transmission of angiostrongyliasis and the risk of disease associated with them". Hawai'i journal of medicine & public health : a journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health. 72 (6 Suppl 2): 70–4. PMID 23901388. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Syed, Sofia. Mulcrone, Renee Sherman; O'Connor, Barry (eds.). "Angiostrongylus cantonensis". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 2006-02-12. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- ↑ Cross, J.H.; Chen, E.R. (2007). "Angiostrongyliasis". Food-Borne Parasitic Zoonoses: Fish and Plant-Borne Parasites. Springer US. pp. 263–290. ISBN 978-0-387-71358-8. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Angiostrongyliasis - Infectious Diseases". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ Graeff-Teixeira, Carlos; Rodriguez, Rubens (1 January 2020). "123 - Abdominal Angiostrongyliasis". Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases (Tenth Edition). Elsevier. pp. 895–897. ISBN 978-0-323-55512-8. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ↑ Alicata JE (1991). "The Discovery of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis as a Cause of Human Eosinophilic Meningitis". Parasitology Today. 7 (6): 151–153. doi:10.1016/0169-4758(91)90285-v. PMID 15463478.

- ↑ "Angiostrongyliasis, Neurologic - Chapter 4 - 2020 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- 1 2 Sawanyawisuth, Kanlayanee; Sawanyawisuth, Kittisak (October 2008). "Treatment of angiostrongyliasis". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 102 (10): 990–996. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.021. ISSN 1878-3503. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ↑ Ortega, Ynés R.; Sterling, Charles R. (24 January 2018). Foodborne Parasites. Springer. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-319-67664-7. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ↑ Chotmongkol V, Sawadpanitch K, et al. (2006). "Treatment of Eosinophilic Meningitis with a Combination of Prednisolone and Mebendazole". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74 (6): 1122–1124. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.1122. PMID 16760531.

- ↑ Lai SC, Chen KM, Chang YH, Lee HH (2008). "Comparative efficacies of albendazole and the Chinese herbal medicine long-dan-xie-gan-tan, used alone or in combination, in the treatment of experimental eosinophilic meningitis induced by Angiostrongylus cantonensis". Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 102 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1179/136485908x252304. PMID 18318936. S2CID 28697541.

- ↑ Knight, Richard (March 2020). "Angiostrongyliasis". Oxford Textbook of Medicine: C8.9.6–C8.9.6.P44. doi:10.1093/med/9780198746690.003.0178. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Chopra, Jagjit; Sawhney, Indermohan (10 November 2015). Neurology in Tropics (e-Book). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 293. ISBN 978-81-312-4233-9. Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ↑ Prevention, CDC-Centers for Disease Control and (11 April 2019). "CDC - Angiostrongylus - Epidemiology & Risk Factors". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ↑ Johnston, David I.; Dixon, Marlena C.; Elm, Joe L.; Calimlim, Precilia S.; Sciulli, Rebecca H.; Park, Sarah Y. (4 September 2019). "Review of Cases of Angiostrongyliasis in Hawaii, 2007–2017". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 101 (3): 608–616. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.19-0280. Archived from the original on 14 December 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ↑ Xiao, Lihua; Ryan, Una; Feng, Yaoyu (6 April 2015). Biology of Foodborne Parasites. CRC Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4665-6885-3. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- 1 2 Thomé, Clarissa (2014-08-04). "Meningite transmitida por parasita avança no Brasil" [Meningitis transmitted by parasite increases in Brazil]. O Estado de S. Paulo (in português). Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

Further reading

- "Parasites - Angiostrongyliasis (also known as Angiostrongylus Infection)". CDC. 2015-12-28. Archived from the original on 2019-11-20. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- "DPDx - Angiostrongyliasis". CDC. 2016-10-17. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2017-04-04. Tabs for Parasite Biology, Image Gallery, Laboratory Diagnosis, and Treatment Information.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|