Diphyllobothrium mansonoides

| Diphyllobothrium mansonoides | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | |

| Subclass: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | Diphyllobothriidae |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | D. mansonoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Diphyllobothrium mansonoides Mueller, 1935 | |

Diphyllobothrium mansonoides (also known as Spirometra mansonoides) is a species of tapeworm (cestodes) that is endemic to North America. Infection with D. mansonoides in humans can result in sparganosis. Justus F. Mueller first reported this organism in 1935. D. mansonoides is similar to D. latum and Spirometra erinacei. When the organism was discovered, scientist did not know if D. mansonoides and S. erinacei were separate species. PCR analysis of the two worms has shown the two to be separate but closely related organisms.[1]

Morphology

Cestodes have a dorso-ventrally flattened shape. Cestodes are segmented worms, and their bodies are divided into three distinct regions: the scolex, the neck, and the strobila.

The scolex is the head of the cestode, and it functions as a holdfast organ that is specialized to attach to intestines using a variety of mechanisms.

Posterior to the scolex is the neck, which is an unsegmented, poorly differentiated region. The neck is where asexual reproduction of proglottid segments occurs. Proglottid segments are individual sets of reproductive organs that compose the rest of the cestode body.

The most posterior section of the cestode body consists of multiple strobila, each being made up of several proglottids. There are 3 stages that proglottids go through in their maturation. The first proglottid stage is the immature stage, characterized by functional reproductive organs. The immature stage is the most anterior proglottid, and consists of anywhere between 200 and 300 proglottids. The mature proglottid is located medially to the other proglottids, and is reproductively functional and hermaphroditic. The most posterior proglottid is the gravid stage, and it is packed with eggs. These eggs are eventually released from the gravid proglottid either through a pore in the proglottid or by disintegration of the proglottid.

Cestodes also have sensory organs in the scolex that detect tactile stimulation. The sensory organs are attached to longitudinal nerves that run along the body and are attached to organs.

Distribution

D. mansonoides is typically found in the southern US. It is especially common in Florida and along the Gulf Coast. D. mansonoides is found in freshwater. The eggs, coracidia and copepods (1st intermediate hosts) inhabit freshwater. The plerocercoids are found in the muscles of hosts. The adult stage is found in various organs (CNS, eye, muscles, etc.) of the definitive host (cat, dog, birds, and other mammals).

Digestion/Metabolism

Cestodes have no digestive tract, and instead, they absorb nutrients along their tegument, which contains microvilli and glycocalyxes. The microvilli are used to absorb nutrients. The glycocalyx is a fuzzy coat that absorbs host enzymes and inhibits host proteases.

Life cycle

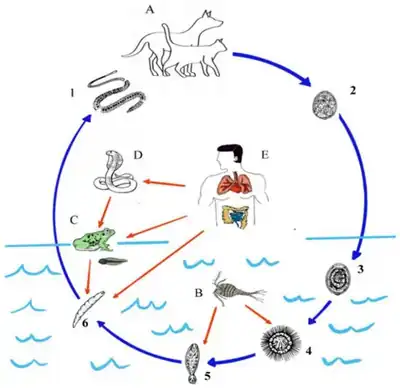

The life cycle is as follows:

- The adult dog or cat drops eggs, which hatch between 9 and 120 days. The coracidium exit the egg through the operculum, a cap in the egg.

- The coracidium is ciliated and swims around in the water, where it is ingested by a copepod.

- The coracidium then sheds its ciliated epithelium, penetrates the midgut wall of the copepod, and develops into the infective procercoid after 18 days.

- The copepod is the 1st intermediate host.

- The procercoid cause the copepod to be sluggish, making it susceptible to be ingested by a 2nd intermediate host, often a frog, snake, or mammal.

- The procercoid penetrates the gut wall and enters the muscles or connective tissues. The procercoid then develops into the plerocercoid.

- The 2nd intermediate host is then eaten by either the definitive host (the bobcat) or a secondary definitive host (a dog or cat). The adult penetrates the intestinal wall and enters the muscles, where it absorbs nutrients.

- Humans can acquire the parasite by ingesting an infected copepod from drinking contaminated water or by eating infected secondary definitive hosts. Therefore, humans can act as 2nd intermediate hosts or paratenic hosts.

Infection

Infection with Diphyllobothrium mansonoides results in sparganosis. Sparganosis is the development of plerocercoids in tissues. There are several routes of human infection:

- When a human mistakenly eats or drinks the procercoid-containing copepod, becoming the 2nd intermediate host.

- When a human ingests the plerocercoid-containing 2nd intermediate host (frog or snake). The human then becomes the paratenic host.

- When a human uses the 2nd intermediate host as a poultice on the skin, vagina, or eyes.

A biopsy of the infected area is conducted to identify the pathogen. Surgical removal of the tapeworm is usually the best method. However, drugs like praziquantel can be administered to treat the infection.

A study was conducted on free-range Florida panthers on the effectiveness of anthelmintic treatment. In the study, the intensity of infection of S. mansonoides increased 6 months after treatment instead of decreasing.[3]

References

- ↑ Lee SU, Huh S, Phares CK (December 1997). "Genetic comparison between Spirometra erinacei and S. mansonoides using PCR-RFLP analysis". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 35 (4): 277–82. doi:10.3347/kjp.1997.35.4.277. PMID 9446910. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ Liu, Wei; Gong, Tengfang; Chen, Shuyu; Liu, Quan; Zhou, Haoying; He, Junlin; Wu, Yong; Li, Fen; Liu, Yisong (18 June 2022). "Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Prevention of Sparganosis in Asia". Animals: an open access journal from MDPI. 12 (12): 1578. doi:10.3390/ani12121578. ISSN 2076-2615. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ↑ Foster GW, Cunningham MW, Kinsella JM, McLaughlin G, Forrester DJ. "Gastrointestinal helminths of free-ranging Florida panthers (Puma concolor coryi) and the efficacy of the current anthelmintic treatment protocol." Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2006 Apr;42(2):402-6