Child mortality

Error: Dataset name contains invalid characters.

Child mortality is the mortality of children under the age of five.[1] The child mortality rate, also under-five mortality rate, refers to the probability of dying between birth and exactly five years of age expressed per 1,000 live births.[2]

It encompasses neonatal mortality and infant mortality (the probability of death in the first year of life).[3]

Reduction of child mortality is reflected in several of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals. Target 3.2 is "by 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce … under‑5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births."[4]

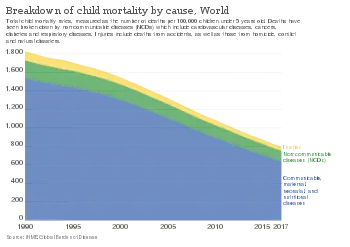

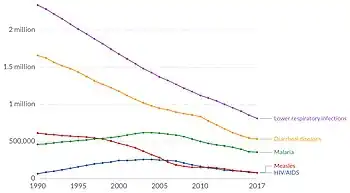

Rapid progress has resulted in a significant decline in preventable child deaths since 1990, with the global under-5 mortality rate declining by over half between 1990 and 2016.[3] While in 1990, 12.6 million children under age five died, in 2016 that number fell to 5.6 million children.[3] However, despite advances, there are still 15,000 under-five deaths per day from largely preventable causes.[3] About 80 per cent of these occur in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and just 6 countries account for half of all under-five deaths: China, India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[3] 45% of these children died during the first 28 days of life.[5] Death rates were highest among children under age 1, followed by children ages 15 to 19, 1 to 4, and 5 to 14.[6]

Many child deaths go unreported for a variety of reasons, including lack of death registration and lack of data on child migrants.[7][8] Without accurate data on child deaths, we cannot fully discover and combat the greatest risks to a child's life.

Measurement

Child mortality refers to number of child deaths under the age of 5 per 1000 live births. More specific terms include:

- Perinatal mortality rate: Number of child deaths within first week of birth ÷ total number of births.[9]

- Neonatal mortality rate: Number of child deaths within first 28 days of life ÷ total number of births.[9]

- Infancy mortality rate: Number of child deaths within first 12 months of life ÷ total number of births.[9]

- Under 5 mortality rates: Number of child deaths within 5th birthday ÷ total number of births.[9]

Causes

The leading causes of death of children under five include:

- Preterm birth complications (18%)

- Pneumonia (16%)

- Interpartum-related events (12%)

- Neonatal sepsis (7%)

- Diarrhea (8%)

- Malaria (5%)

- Malnutrition and Under nutrition

There is variation of child mortality around the world. Countries that are in the second or third stage of the Demographic Transition Mode (DTM) have higher rates of child mortality than countries in the fourth or fifth stage. Chad infant mortality is about 96 per 1,000 live births, compared to only 2.2 per 1,000 live births in Japan.[9] In 2010, there was a global estimate of 7.6 million child deaths with most occurring in less developed countries. Among those, 4.7[10] million died from infection and disorder.[10] Child mortality is not only caused by infection and disorder: it is also caused by premature birth; birth defect; new born infection; birth complication; and diseases like malaria, sepsis, and diarrhea.[11] In less developed countries, malnutrition is the main cause of child mortality.[11] Pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria together are the cause of 1 out of every 3 deaths before the age of 5 while nearly half of under-five deaths globally are attributable to under-nutrition.[12]

Prevention

Child survival is a field of public health concerned with reducing child mortality. Child survival interventions are designed to address the most common causes of child deaths that occur, which include diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and neonatal conditions. Of the portion of children under the age of 5 alone, an estimated 5.6 million children die each year mostly from such preventable causes.[13]

The child survival strategies and interventions are in line with the fourth Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which focused on reducing child mortality by 2/3 of children under five before the year 2015. In 2015, the MDGs were replaced with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to end these deaths by 2030. In order to achieve SDG targets, progress must be accelerated in more than 1/4 of all countries (most of which are in sub-Saharan Africa) in order to achieve targets for under-5 mortality, and in 60 countries (many in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia) to achieve targets for neonatal mortality.[13] Without accelerated progress, 60 million children under age 5 will die between 2017 and 2030, about half of which would be newborns. China achieved its target of reduction in under-5 mortality rates well ahead of schedule.[14]

Low-cost interventions

Two-thirds of child deaths are preventable.[15] Most of the children who die each year could be saved by low-tech, evidence-based, cost-effective measures such as vaccines, antibiotics, micronutrient supplementation, insecticide-treated bed nets, improved family care and breastfeeding practices,[16] and oral rehydration therapy.[17] Empowering women, removing financial and social barriers to accessing basic services, developing innovations that make the supply of critical services more available to the poor and increasing local accountability of health systems are policy interventions that have allowed health systems to improve equity and reduce mortality.[18]

In developing countries, child mortality rates related to respiratory and diarrheal diseases can be reduced by introducing simple behavioral changes, such as handwashing with soap. This simple action can reduce the rate of mortality from these diseases by almost 50 per cent.[19]

Proven, cost-effective interventions can save the lives of millions of children per year. The UN Vaccine division as of 2014 supported 36% of the world's children in order to best improve their survival chances, yet still, low-cost immunization interventions do not reach 30 million children despite success in reducing polio, tetanus, and measles.[20] Measles and tetanus still kill more than 1 million children under 5 each year. Vitamin A supplementation costs only $0.02 for each capsule and given 2–3 times a year will prevent blindness and death. Although vitamin A supplementation has been shown to reduce all-cause mortality by 12 to 24 per cent, only 70 per cent of targeted children were reached in 2015.[13] Between 250,000 and 500,000 children become blind every year, with 70 percent of them dying within 12 months. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is an effective treatment for lost liquids through diarrhea; yet only 4 in 10 (44 per cent) of children ill with diarrhea are treated with ORT.[13]

Essential newborn care - including immunizing mothers against tetanus, ensuring clean delivery practices in a hygienic birthing environment, drying and wrapping the baby immediately after birth, providing necessary warmth, and promoting immediate and continued breastfeeding, immunization, and treatment of infections with antibiotics - could save the lives of 3 million newborns annually. Improved sanitation and access to clean drinking water can reduce childhood infections and diarrhea. Over 30% of the world's population does not have access to basic sanitation, and 844 million people use unsafe sources of drinking water.[21]

Efforts

Agencies promoting and implementing child survival activities worldwide include UNICEF and non-governmental organizations; major child survival donors worldwide include the World Bank, the British Government's Department for International Development, the Canadian International Development Agency and the United States Agency for International Development. In the United States, most non-governmental child survival agencies belong to the CORE Group, a coalition working, through collaborative action, to save the lives of young children in the world's poorest countries.

Epidemiology

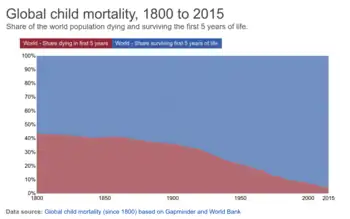

Child mortality has been dropping as each country reaches a high stage of DTM. From 2000 to 2010, child mortality has dropped from 9.6 million to 7.6 million. In order to reduce child mortality rates, there needs to be better education, higher standards of healthcare and more caution in childbearing. Child mortality could be reduced by attendance of professionals at birth and by breastfeeding and through access to clean water, sanitation, and immunization.[11] In 2016, the world average was 41 (4.1%), down from 93 (9.3%) in 1990.[3] This is equivalent to 5.6 million children less than five years old dying in 2016.[3]

Global child mortality over time

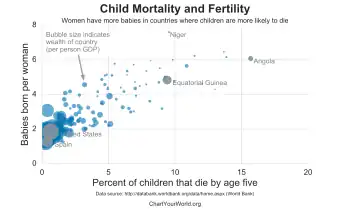

Global child mortality over time Child mortality is high in countries where women have many children (high fertility rates). Wealthy countries have lower child mortality rates than poor ones.

Child mortality is high in countries where women have many children (high fertility rates). Wealthy countries have lower child mortality rates than poor ones.

Variation

Huge disparities in under-5 mortality rates exist. Globally, the risk of a child dying in the country with the highest under-5 mortality rate is about 60 times higher than in the country with the lowest under-5 mortality rate.[3] Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the highest under-5 mortality rates in the world: All six countries with rates above 100 deaths per 1,000 live births are in sub-Saharan Africa, with Somalia having the highest under-5 mortality rates.[22][3]

Furthermore, approximately 80% of under-5 deaths occur in only two regions: sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.[3] 6 countries account for half of the global under-5 deaths, namely, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia and China.[3] India and Nigeria alone account for almost a third (32 per cent) of the global under-five deaths.[3] Within low- and middle-income countries, there is also substantial variation in child mortality rates across administrative divisions.[23][24]

Likewise, there are disparities between wealthy and poor households in developing countries. According to a Save the Children paper, children from the poorest households in India are three times more likely to die before their fifth birthday than those from the richest households.[25] A systematic study reports for all the low- and middle-income countries (not including China), the children among the poorest households are twice as likely to die before the age of 5 years old compare to those in the richest household.[26]

A large team of researchers published a major study on the global distribution of child mortality in Nature in October 2019.[27] It was the first global study that mapped child death on the level of subnational district (17,554 units). The study was described as an important step to make action possible that further reduces child mortality.[28]

The child survival rate of nations varies with factors such as fertility rate and income distribution; the change in distribution shows a strong correlation between child survival and income distribution as well as fertility rate, where increasing child survival allows the average income to increase as well as the average fertility rate to decrease.[29][30]

See also

References

- ↑ "WHO | Child mortality and causes of death". WHO. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ↑ "UNICEF - Definitions". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "UNICEF Child Mortality Statistics". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Martin. "Health". United Nations Sustainable Development. Archived from the original on 2019-09-20. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ↑ Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, Zhu J, et al. (December 2016). "Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals". Lancet. 388 (10063): 3027–3035. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31593-8. PMC 5161777. PMID 27839855.

- ↑ "Infant, Child, and Teen Mortality". Archived from the original on 2022-01-28. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ "A Snapshot of Civil Registration in Sub-Saharan Africa". UNICEF. 2017-12-05. Archived from the original on 2022-01-28. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "A Child is a Child: Protecting children on the move from violence, abuse and exploitation". UNICEF. 2017-05-18. Archived from the original on 2018-04-05. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Weeks JR (2015-01-01). Population : an introduction to concepts and issues (Twelfth ed.). Boston, MA. ISBN 9781305094505. OCLC 884617656.

- 1 2 "Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000". ProQuest 1023015914.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 "Child mortality: Top causes, best solutions | World Vision". World Vision. 2016-01-13. Archived from the original on 2018-04-11. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ↑ "UNICEF STATISTICS". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "UNICEF STATISTICS". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "MDGs Global Report 2015". United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 2021-05-18. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ UNICEF - Young child survival and development Archived 2013-10-14 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "UNICEF - Goal: Reduce child mortality". Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "WHO - New formula for oral rehydration salts will save millions of lives". Archived from the original on August 25, 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "Surveys - UNICEF MICS" (PDF). www.childinfo.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ Curtis V, Cairncross S (May 2003). "Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 3 (5): 275–81. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00606-6. PMID 12726975.

- ↑ Jadhav S, Gautam M, Gairola S (May 2014). "Role of vaccine manufacturers in developing countries towards global healthcare by providing quality vaccines at affordable prices". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 Suppl 5: 37–44. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12568. PMID 24476201.

- ↑ "Water, sanitation and hygiene overview". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 2020-04-19. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ "Under-five mortality". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 2020-04-23. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ↑ Golding N, Burstein R, Longbottom J, Browne AJ, Fullman N, Osgood-Zimmerman A, et al. (November 2017). "Mapping under-5 and neonatal mortality in Africa, 2000-15: a baseline analysis for the Sustainable Development Goals". Lancet. 390 (10108): 2171–2182. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31758-0. PMC 5687451. PMID 28958464.

- ↑ Burstein R, Henry NJ, Collison ML, Marczak LB, Sligar A, Watson S, et al. (October 2019). "Mapping 123 million neonatal, infant and child deaths between 2000 and 2017". Nature. 574 (7778): 353–358. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..353B. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1545-0. PMC 6800389. PMID 31619795.

- ↑ Inequalities in child survival: looking at wealth and other socio-economic disparities in developing countries Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Chao, Fengqing; You, Danzhen; Pedersen, Jon; Hug, Lucia; Alkema, Leontine (May 2018). "National and regional under-5 mortality rate by economic status for low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic assessment". Lancet Global Health. 6 (5): e535–e547. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30059-7. PMC 5905403. PMID 29653627.

- ↑ Burstein, Roy; Henry, Nathaniel J.; Collison, Michael L.; Marczak, Laurie B.; Sligar, Amber; Watson, Stefanie; Marquez, Neal; Abbasalizad-Farhangi, Mahdieh; Abbasi, Masoumeh; Abd-Allah, Foad; Abdoli, Amir (October 2019). "Mapping 123 million neonatal, infant and child deaths between 2000 and 2017". Nature. 574 (7778): 353–358. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..353B. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1545-0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6800389. PMID 31619795.

- ↑ Bachelet, Michelle (2019-10-16). "Data on child deaths are a call for justice". Nature. 574 (7778): 297. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..297B. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03058-6. PMID 31619786.

- ↑ Dadonaite, Bernadeta; Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (10 May 2013). "Child & Infant Mortality". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ↑ "Hans Rosling shows the best stats you've ever seen". TED talks. TED Conferences. February 2006. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

External links

- "Child mortality estimates for all countries". UNICEF]. Archived from the original on 2015-04-24. Retrieved 2022-03-15.

- "Visualization of child mortality from 2000-2017 in low- and middle-income countries". Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Archived from the original on 2022-01-28. Retrieved 2021-12-13.