Pentosan polysulfate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Pentosan polysulfate sodium, (1->4)-β-Xylan 2,3-bis(hydrogen sulfate) with a 4 O-methyl-α-D-glucuronate |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Heparinoid[1] |

| Main uses | Interstitial cystitis[1] |

| Side effects | Hair loss, diarrhea, nausea, blood in the stool, rash, liver problems, abdominal pain[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 100 mg TID[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Chemical and physical data | |

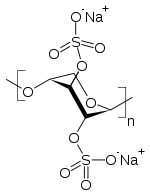

| Formula | (C5H6Na2O10S2)n |

Pentosan polysulfate (PPS), sold under the brand name Elmiron among others, is a medication used for bladder pain syndrome.[1] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include hair loss, diarrhea, nausea, blood in the stool, rash, liver problems, and abdominal pain.[1] Other side effects may include eye problems and infection.[2] It is a partly manufactured heparinoid.[1] It is believed to work by attaching to the bladder wall protecting it.[3]

Pentosan polysulfate was approved for medical use in the United States in 1996 and Europe in 2017.[1] In the United States it costs about 900 USD per month as of 2021.[3] In the United Kingdom this amount costs the NHS about £450.[2]

Medical uses

Bladder pain syndrome

Pentosan polysulfate may be used either by mouth or in the bladder to treat interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (IC/PBS).[4] An older review found improvements in pain (36%), urgency (28%), and frequency (54%), but that it does not change the frequency of urination at night.[4][5] More recent trials, however, found it to be of no benefit.[4]

Osteoarthritis

PPS has been studied in knee osteoarthritis, though evidence to support such use is poor as of 2003.[6] There is some theoretical evidence that it should help.[7]

Dosage

It is taken at a dose of 100 mg three times per day.[1]

Side effects

People who have taken PPS orally report a variety of side effects, primarily gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea, heartburn, and stomach pain.[8] Hair loss, headache, rash, and insomnia have also been reported.[8] Due to Elmiron's anticoagulant effects, some patients report bruising more easily. In some cases, patients are asked to stop taking the medication before any major surgical procedures to reduce the likelihood of bleeding. Recent report based on clinical observation hypothesizes that chronic exposure to PPS can cause retinal toxicity, mimicking pigmentary pattern dystrophy.[9][10][11]

Mechanism of action

In IC, PPS is believed to work by providing a protective coating to the damaged bladder wall. PPS is similar in structure to the natural glycosaminoglycan coating of the inner lining of the bladder, and may replace or repair the lining, reducing its permeability.[9]

History

The calcium salt of PPS was one of the first reported disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOAD).[10]

Society and culture

Names

The IUPAC name for pentosan polysulfate is [(2R,3R,4S,5R)-2-hydroxy-5-[(2S,3R,4S,5R)-5-hydroxy-3,4-disulfooxyoxan-2-yl]oxy-3-sulfooxyoxan-4-yl] hydrogen sulfate.

There are 40 synonyms listed for pentosan polysulfate on PubChem including BAY-946, HOE-946, pentosan sulfuric polyester, polypentose sulfate, polysulfated xylan, PZ-68, SP-54, xylan SP54 and xylan sulfate.

Various brand names include Elmiron (as sodium salt), Hemoclar, Anarthron, Fibrase, Fibrocid, Thrombocid and SP54. PPS capsules are sold in India under the brand names Comfora, Pentossan-100, Cystopen and For-IC. In the veterinary field, pentosan polysulfate is sold as Cartrophen Vet and Sylvet by Biopharm Australia, Pentosan by Naturevet Australia, Anarthron by Randlab Australia and Zydax by Parnell.

Research

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

PPS is being studied as a potential treatment of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD). The rationale for this treatment was unclear but it was subsequently shown in prion-infected mouse neuroblastoma cells that PPS could rapidly reduce the levels of abnormal (scrapie) prion without affecting the normal cellular isoform.[12] As PPS can bind to the cellular isoform of the prion protein, it may stabilise this form and prevent its conversion to the pathological (scrapie) isoform.[13]

The treatment[14] of one patient in Northern Ireland and around six other patients in mainland Britain was reported in the press.[15]

Other animals

Dogs

Read et al. (1996) [16] used three different doses of sodium PPS to treat 40 geriatric dogs with well-established clinical signs of chronic OA with SC injection. The 3 mg/kg dose was the most effective. In a study conducted with 10 elderly dogs with osteoarthritis given calcium PPS (3 mg/kg intramuscularly) once weekly for four weeks, the improvement in symptoms (seen at 1, 2, 3 and 7 weeks after initiation of therapy) was found to correlate with plasma indices of fibrinolytic activity and lipid profiles.[17] In a study in dogs with OA secondary to cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) deficiency, although no differences were identified in either functional outcome or radiographic progression using the oral calcium PPS compared with placebo, there were significantly lower levels of proteoglycan breakdown products in the synovial fluid of the osteoarthritic joints.[18] The efficacy of subcutaneous sodium PPS (3 mg/kg) was tested in 40 dogs with cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) instability and found to hasten recovery, as measured by more rapidly improved ground reaction forces (GRF), over 48 weeks.[19]

Horses

There are few published reports describing the use of PPS for equine joint disease; however, the drug is being used for this indication in Australia. When administered to racing Thoroughbreds with chronic osteoarthritis (2 to 3 mg/kg, intramuscularly, once weekly for 4 weeks, then as required), PPS treatment improved but did not eliminate clinical signs of joint disease.[20] Articular cartilage fibrillation was substantially reduced by similar NaPPS treatment intramuscularly in nine horse with experimentally-induced carpal osteoarthritis.[21] Despite limited published studies on the effect of PPS in horses, most surveyed owners and trainers in Australia found the intramuscular PPS treatment to be highly efficacious when used as a prophylactic prior to competition.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Pentosan Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- 1 2 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 835. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- 1 2 "Elmiron Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Giusto, LL; Zahner, PM; Shoskes, DA (July 2018). "An evaluation of the pharmacotherapy for interstitial cystitis". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 19 (10): 1097–1108. doi:10.1080/14656566.2018.1491968. PMID 29972328. S2CID 49674883.

- ↑ Hwang P, Auclair B, Beechinor D, Diment M, Einarson TR (July 1997). "Efficacy of pentosan polysulfate in the treatment of interstitial cystitis: a meta-analysis". Urology. 50 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00110-6. PMID 9218016.

- ↑ Uthman, I; Raynauld, JP; Haraoui, B (August 2003). "Intra-articular therapy in osteoarthritis". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (934): 449–53. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.934.449. PMC 1742771. PMID 12954956.

- ↑ Ghosh, P (1999). "The pathobiology of osteoarthritis and the rationale for the use of pentosan polysulfate for its treatment". Semin Arthritis Rheum. 28 (4): 211–67. doi:10.1016/s0049-0172(99)80021-3. PMID 10073500.

- 1 2 Pubmed Health (2012). "Pentosan Polysulfate". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- 1 2 Parsons CL (1994). "The therapeutic role of sulfated polysaccharides in the urinary bladder". Urol Clin North Am. 21 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1016/S0094-0143(21)00597-8. PMID 7904388.

- 1 2 Ghosh, P; Smith, M (2002). "Osteoarthritis, genetic and molecular mechanisms". Biogerontology. 3 (1–2): 85–8. doi:10.1023/a:1015219716583. PMID 12014849. S2CID 33755966.

- ↑ Hanif, Adam M.; Armenti, Stephen T.; Taylor, Stanford C.; Shah, Rachel A.; Igelman, Austin D.; Jayasundera, K. Thiran; Pennesi, Mark E.; Khurana, Rahul N.; Foote, Jenelle E.; o'Keefe, Ghazala A.; Yang, Paul; Hubbard, G. Baker; Hwang, Thomas S.; Flaxel, Christina J.; Stein, Joshua D.; Yan, Jiong; Jain, Nieraj (2019). "Phenotypic Spectrum of Pentosan Polysulfate Sodium–Associated Maculopathy". JAMA Ophthalmology. 137 (11): 1275–1282. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.3392. PMC 6735406. PMID 31486843.

- ↑ Yamasaki, Takeshi; Suzuki, Akio; Hasebe, Rie; Horiuchi, Motohiro (2014). "Comparison of the Anti-Prion Mechanism of Four Different Anti-Prion Compounds, Anti-PrP Monoclonal Antibody 44B1, Pentosan Polysulfate, Chlorpromazine, and U18666A, in Prion-Infected Mouse Neuroblastoma Cells". PLOS ONE. 9 (9): e106516. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j6516Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106516. PMC 4152300. PMID 25181483.

- ↑ Kamatari, Yuji O; Hayano, Yosake; Yamaguchi, Kei-ichi; Hosokawa-Muto, Junji; Kuwata, Kazuo (2012). "Characterizing antiprion compounds based on their binding properties to prion proteins: Implications as medical chaperones". Protein Sci. 22 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1002/pro.2180. PMC 3575857. PMID 23081827.

- ↑ Whittle, IR; Knight, RS; Will, RG (2006). "Unsuccessful intraventricular pentosan polysulphate treatment of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 148 (6): 677–679. doi:10.1007/s00701-006-0772-y. PMID 16598408. S2CID 37400744.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | Health | Research will now assess CJD drug". Archived from the original on 2021-01-29. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ↑ Read, RA; Cullis-Hill, D; Jones, MP (1996). "Systemic use of pentosan polysulphate in the treatment of osteoarthritis". J Small Anim Pract. 37 (3): 108–114. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1996.tb02355.x. PMID 8683953.

- ↑ Ghosh, P; Cheras, PA (2001). "Vascular mechanisms in osteoarthritis". Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 15 (5): 693–709. doi:10.1053/berh.2001.0188. PMID 11812016.

- ↑ Innes, JF; Barr, AR; Sharif, M (2000). "Efficacy of oral calcium pentosan polysulphate for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the canine stifle joint secondary to cranial cruciate ligament deficiency". Vet Rec. 146 (15): 433–437. doi:10.1136/vr.146.15.433. PMID 10811265. S2CID 46623547.

- ↑ Budsberg, SC; Bergh, MS; Reynolds, LR; Streppa, HK (2007). "Evaluation of pentosan polysulfate sodium in the postoperative recovery from cranial cruciate injury in dogs: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial". Vet Surg. 36 (3): 234–244. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950x.2007.00256.x. PMID 17461948.

- ↑ Little, CB; Ghosh, P (1996). McIlwraith, CW; Trotter, GW (eds.). Joint Disease in the Horse. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company. pp. 281–292.

- ↑ McIlwraith, CW; Frisbie, DD; Kawcak, CE (2012). "Evaluation of intramuscularly administered sodium pentosan polysulfate for treatment of experimentally induced osteoarthritis in horses". Am J Vet Res. 73 (5): 628–633. doi:10.2460/ajvr.73.5.628. PMID 22533393.

- ↑ Kramer, CM; Tsang, AS; Koenig, T; Jeffcott, LB; Dart, CM; Dart, AJ (2014). "Survey of the therapeutic approach and efficacy of pentosan polysulfate for the prevention and treatment of equine osteoarthritis in veterinary practice in Australia". Aust Vet J. 92 (12): 482–487. doi:10.1111/avj.12266. PMID 25424761.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|