Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Segmental glomerulosclerosis, focal sclerosis with hyalinosis, familial idiopathic nephrotic syndrome[1] | |

| |

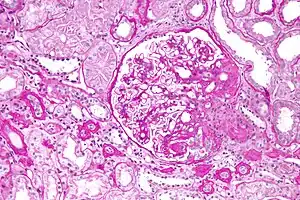

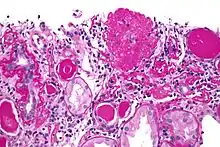

| Light micrograph of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, hilar variant. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain. | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| Symptoms | Foamy urine, swelling[2][1] |

| Complications | High blood pressure, kidney failure[2][3] |

| Types | Primary, secondary[3] |

| Causes | Unknown, genetics, certain medications, vesicoureteral reflux, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, HIV/AIDS[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Kidney biopsy[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, lupus, other causes of nephrotic syndrome[3] |

| Treatment | Immunosuppressants, blood pressure control[2][3] |

| Frequency | 7 per million people[4] |

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) is a type of scarring in the kidney.[4] Symptoms may include protein in the urine and swelling.[1][2] Complications may include high blood pressure and kidney failure.[2][3]

The cause is often unclear.[1] Other cases may occur due to genetics, certain medications, vesicoureteral reflux, obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, or HIV/AIDS.[1][3] The underlying mechanism involves scarring of parts of some of the glomeruli due to injury of podocytes.[3] A kidney biopsy may confirm the diagnosis, but early in the disease a normal biopsy may not exclude it.[2]

Treatment involves the use of immunosuppressants such as steroids, tacrolimus, or rituximab.[3] Blood pressure may be managed with ACE inhibitors and swelling may be treated with diuretics.[2][3] If kidney failure occurs, dialysis or kidney transplant may be requires.[4]

FSGS affects about 7 per million people.[4] It is the cause of about 40% of cases of nephrotic syndrome (high levels of protein in the urine) in adults and 20% in children.[3] The condition was first described in 1925 by Fahr.[5]

Classification

Depending on the cause it is broadly classified as:

- Primary, when no underlying cause is found; usually presents as nephrotic syndrome

- Secondary, when an underlying cause is identified; usually presents with kidney failure and proteinuria. This is actually a heterogeneous group including numerous causes such as

- Toxins and drugs such as heroin and pamidronate

- Familial forms

- Secondary to nephron loss and hyperfiltration, such as with chronic pyelonephritis and reflux, morbid obesity, diabetes mellitus

There are many other classification schemes also.

Pathologic variants

Five mutually exclusive variants of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis may be distinguished by the pathologic findings seen on renal biopsy:[6]

- Collapsing variant

- Glomerular tip lesion variant

- Cellular variant

- Perihilar variant

- Not otherwise specified (NOS) variant.

Recognition of these variants may have prognostic value in individuals with primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (i.e. where no underlying cause is identified). The collapsing variant is associated with higher rate of progression to end-stage renal disease, whereas glomerular tip lesion variant has a low rate of progression to end-stage renal disease in most patients. Cellular variant shows similar clinical presentation to collapsing and glomerular tip variant but has intermediate outcomes between these two variants. However, because collapsing and glomerular tip variant show overlapping pathologic features with cellular variant, this intermediate difference in clinical outcomes may reflect a sampling bias in cases of cellular focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (i.e. unsampled collapsing variant or glomerular tip variant). The prognostic significance of perihilar and NOS variants has not yet been determined. The NOS variant is the most common subtype. Collapsing variant is the most common type of glomerulopathy caused by HIV infection.

Causes

Some general secondary causes are listed below:

- Glomerular hypertrophy/hyperfiltration

- Unilateral renal agenesis

- Morbid obesity

- Scarring due to previous injury

- Focal proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Vasculitis

- Lupus

- Toxins (pamidronate)

- Human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy

- Heroin nephropathy[7]

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis may develop following acquired loss of nephrons from reflux nephropathy. Proteinuria is nonselective in most cases and may be in subnephrotic range (nephritic range <3.0gm/24hr) or nephritic range.[8]

Genetics

There are currently several known genetic causes of the hereditary forms of FSGS.

| Gene | OMIM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| FSGS1: ACTN4 | 603278 | The first gene involved with this disorder is ACTN4, which encodes alpha-actinin 4. This protein crosslinks bundles of actin filaments and is present in the podocyte. Mutations in this protein associated with FSGS result in increased affinity for actin binding, formation of intracellular aggregates, and decreased protein half-life. While it is unclear how these effects might lead to FSGS there are a number of theories. Firstly, protein aggregation may have a toxic effect on the podocyte. Secondly, decreased protein half-life or increased affinity for actin binding may alter actin polymerization and thereby affect the podocytes cytoskeletal architecture.[9] |

| FSGS2: TRPC6 | 603965 | A second gene associated with FSGS is TRPC6, which encodes a member of the canonical family of TRP channels. This family of ion channels conduct cations in a largely non-selective manner. As with ACTN4, TRPC6 is expressed in podocytes. While TRP channels can be activated through a variety of methods, TRPC6 is known to be activated by phospholipase C stimulation. There are at least 6 mutations in this channel, located throughout the channel. At least one of these mutations, P112Q, leads to increased intracellular calcium influx. It is unclear how this might lead to FSGS, though it has been proposed that it may result in alteration of podocyte dynamics or podocytopenia.[9] |

| FSGS3: CD2AP | 607832 | Another gene that may be involved in hereditary forms of FSGS is the gene known as CD2AP (CD2 associated protein) or CMS (Cas binding protein with multiple SH3 domains). The protein expressed by this gene is expressed in podocytes where it interacts with fyn and synaptopodin. There is a report that a splicing mutation in this gene was found in two patients with HIV associated FSGS and this led to altered protein translation. This has been theorized to result in altered actin binding and, thus, alteration of the cytoskeletal podocyte architecture.[9] |

| FSGS4: APOL1 | 612551 | In people of African descent, two common variants in APOL1 have been associated with FSGS. It is believed that these variants arose as a defensive mechanism against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense or some other sub-Saharan parasite despite conferring high susceptibility to FSGS when inherited from both parents.[10] |

| FSGS5: INF2 | 613237 | Another gene associated with FSGS is INF2, which encodes a member of the formin family of actin-regulating proteins. The observation that alterations in this podocyte-expressed formin cause FSGS emphasizes the importance of fine regulation of actin polymerization in podocyte function.[11] |

| SRN1: NPHS2 | 600995 | Mutations in the NPHS2 gene, which codes for the protein called podocin,[12] can cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis.[13] This is a recessive form of FSGS.[14] An affected individual has two mutant copies of the NPHS2 gene, in contrast to ACTN4 and TRPC6 mediated forms of disease, which are dominant and require only one mutant copy of the gene. NPHS2-mediated FSGS is resistant to treatment with steroids. |

Some researchers found SuPAR as a cause of FSGS. [15] Another gene that has been associated with this syndrome is the COL4A5 gene.[16]

Diagnosis

In children and some adults, FSGS presents as a nephrotic syndrome, which is characterized by edema (associated with weight gain), hypoalbuminemia (low serum albumin, a protein in the blood), hyperlipidemia and hypertension (high blood pressure). In adults, it may also present as kidney failure and proteinuria, without a full-blown nephrotic syndrome.

Tests

- Urinalysis

- Blood tests — cholesterol

- Kidney biopsy

Differential diagnosis

- Minimal change disease (MCD), especially in children

- Membranous glomerulonephritis

- Several other

MCD is a more common cause of nephrotic syndrome in children: MCD and primary FSGS may have a similar cause.[17]

Treatment

Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs

Epidemiology

FSGS affects about 7 per million people.[4] It is the cause of about 40% of cases of nephrotic syndrome (high levels of protein in the urine) in adults and 20% in children.[3] African Americans are more frequently affected.[18]

Word origin

The individual components of the name refer to the appearance of the kidney tissue on biopsy: focal—only some of the glomeruli are involved (as opposed to diffuse), segmental—only part of each glomerulus is involved (as opposed to global),[19] glomerulosclerosis—refers to scarring of the glomerulus (a part of the nephron (the functional unit of the kidney)). The glomerulosclerosis is usually indicated by heavy PAS staining and findings of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and C3-convertase (C3) in the sclerotic segment.[20]

Notable cases

- Former NBA basketball players Sean Elliott and Alonzo Mourning have both survived bouts with FSGS. Mourning is an Ambassador to the NephCure Foundation. Pro bodybuilder Flex Wheeler was diagnosed with FSGS and had a kidney transplant. Former MLS player Clyde Simms retired from professional soccer in 2014 due to FSGS.[21]

- Gary Coleman American actor, known for his childhood role as Arnold Jackson in the American sitcom Diff'rent Strokes.

- Andy Cole, former Newcastle Utd, Manchester United and England international football player[22]

- Ed Hearn, former Major League Baseball player for the New York Mets and Kansas City Royals

- Aries Merritt, 110 metres hurdles world record holder and 2012 Olympic champion, had a kidney transplant for collapsing FSGS days after coming third in the 2015 World Championships.[23]

- Natalie Cole, American singer[24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Glomerular Diseases | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Guruswamy Sangameswaran, KD; Baradhi, KM (January 2020). "Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis". PMID 30335305.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 "Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Jennette, J. Charles (2007). Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-7817-4750-9. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ↑ Thomas DB, Franceschini N, Hogan SL, et al. (2006). "Clinical and pathologic characteristics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis pathologic variants". Kidney Int. 69 (5): 920–6. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000160. PMID 16518352.

- ↑ Burtis, C.A.; Ashwood, E.R. and Bruns, D.E. Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics. 5th Edition. Elsevier. pp1566

- ↑ Harrison

- 1 2 3 Mukerji N, Damodaran TV, Winn MP (2007). "TRPC6 and FSGS: The latest TRP channelopathy" (PDF). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1772 (8): 859–68. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.03.005. PMID 17459670. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-03. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- ↑ Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, Bernhardy AJ, Hicks PJ, Nelson GW, Vanhollebeke B, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Pays E, Pollak MR (Jul 2010). "Association of Trypanolytic ApoL1 Variants with Kidney Disease in African-Americans". Science. 329 (5993): 841–5. Bibcode:2010Sci...329..841G. doi:10.1126/science.1193032. PMC 2980843. PMID 20647424.

- ↑ Brown EJ, Schlöndorff JS, Becker DJ, Tsukaguchi H, Uscinski AL, Higgs HN, Henderson JM, Pollak MR (Jan 2010). "Mutations in the formin protein INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis". Nature Genetics. 42 (1): 72–6. doi:10.1038/ng.505. PMC 2980844. PMID 20023659.

- ↑ Tsukaguchi H, Sudhakar A, Le TC, et al. (December 2002). "NPHS2 mutations in late-onset focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: R229Q is a common disease-associated allele". J. Clin. Invest. 110 (11): 1659–66. doi:10.1172/JCI16242. PMC 151634. PMID 12464671.

- ↑ Franceschini N, North KE, Kopp JB, McKenzie L, Winkler C (February 2006). "NPHS2 gene, nephrotic syndrome and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a HuGE review". Genet. Med. 8 (2): 63–75. doi:10.1097/01.gim.0000200947.09626.1c. PMID 16481888.

- ↑ Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, Benessy F, Lee H, Fuchshuber A, Dahan K, Gubler MC, Niaudet P, Antignac C (May 2000). "NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome". Nature Genetics. 24 (4): 349–354. doi:10.1038/74166. PMID 10742096.

- ↑ https://www.revistanefrologia.com/en-supar-focal-segmental-glomerulosclerosis-articulo-X2013251414053834.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website=|title=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Zhang J, Yang J, Hu Z (2017) Study of a family affected with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis due to mutation of COL4A5 gene. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi 34(3):373-376 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2017.03.013

- ↑ Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A, eds. (2003). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Saunders. pp. 982–3. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ↑ Rhadhakrishnan, Jai M.; Appel, Gerald B. (2020). "113. Glomerular disorders and nephrotic syndromes". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 1 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 756. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ↑ "Focal_segmental_glomerulosclerosis of the Kidney". Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ↑ "Focal_segmental_glomerulosclerosis of the Kidney". Archived from the original on 2014-08-22. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ↑ "Kidney disease forces former New England Revolution, DC United M Clyde Simms to retire". 2014-02-13. Archived from the original on 2014-07-09. Retrieved 2014-02-13.

- ↑ "Andy Cole reveals he's been suffering from kidney failure". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ↑ Clarey, Christopher (28 August 2015). "Days Before Kidney Transplant, Aries Merritt Wins Bronze in Hurdles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ↑ "Autopsy: The Last Hours of Natalie Cole." Autopsy. Nar. Eric Meyers. Exec. Prod. Ed Taylor and Michael Kelpie. Reelz, 27 May 2017. Television.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |