Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

Prevenar 13 | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Streptococcus pneumoniae |

| Type | Conjugate vaccine |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Prevnar 20, Prevnar 13, Synflorix, others |

| Clinical data | |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Routes of use | Intramuscular |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607021 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) is a pneumococcal vaccine that prevents pneumonia due to the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae in infants, young children, and adults.[5] It is a conjugate vaccine and contains purified capsular polysaccharide of pneumococcal serotypes conjugated to a carrier protein to improve antibody response compared to the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.[5][6]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of the conjugate vaccine in routine immunizations given to children.[5]

The most common side effects in children are decreased appetite, fever (only very common in children aged six weeks to five years), irritability, reactions at the site of injection (reddening or hardening of the skin, swelling, pain or tenderness), somnolence (sleepiness) and poor quality sleep.[7] In adults and the elderly, the most common side effects are decreased appetite, headaches, diarrhea, fever (only very common in adults aged 18 to 29 years), vomiting (only very common in adults aged 18 to 49 years), rash, reactions at the site of injection, limitation of arm movement, arthralgia and myalgia (joint and muscle pain), chills and fatigue.[7] Paracetamol may reduce common, minor adverse reactions (fever, pain, swelling, tenderness).[8]

Efficacy

Prevnar-7 is designed to stop seven of about ninety pneumococcal serotypes which have the potential to cause invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). In 2010, a 13-valent vaccine was introduced. Each year, IPD kills approximately one million children worldwide.[10] Since approval, Prevnar's efficacy in preventing IPD has been documented by a number of epidemiologic studies.[11][12][13] There is evidence that other people in the same household as a vaccinee also become relatively protected.[14] There is evidence that routine childhood vaccination reduces the burden of pneumococcal disease in adults and especially high-risk adults, such as those living with HIV/AIDS.[15]

The vaccine is, however, primarily developed for the U.S. and European epidemiological situation, and therefore it has only a limited coverage of serotypes causing serious pneumococcal infections in most developing countries.[16]

Routine vaccination

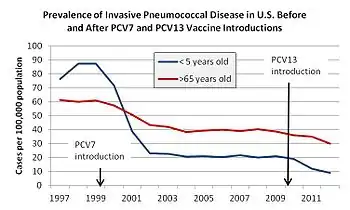

After introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in 2000, several studies described a decrease in invasive pneumococcal disease in the United States. One year after its introduction, a group of investigators found a 69% drop in the rate of invasive disease in those of less than two years of age.[11] By 2004, all-cause pneumonia admission rates had declined by 39% (95% CI 22–52) and rates of hospitalizations for pneumococcal meningitis decreased by 66% (95% CI 56.3-73.5) in children younger than 2.[17][18]

Rates of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults have also declined since the introduction of the vaccine.[11][18]

Low-income countries

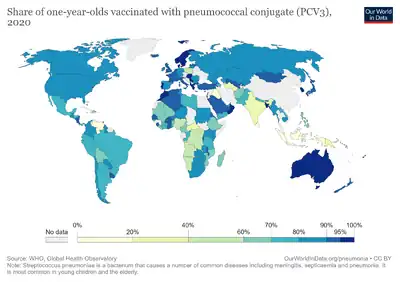

Pneumococcal disease is the leading vaccine-preventable killer of young children worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). It killed more than 500,000 children younger than five years of age in 2008 alone.[19] Approximately ninety percent of these deaths occur in the developing world.[19] Historically 15–20 years pass before a new vaccine reaches one quarter of the population of the developing world.[20]

Pneumococcal vaccines Accelerated Development and Introduction Plan (PneumoADIP) was a GAVI Alliance (GAVI) funded project to accelerate the introduction of pneumococcal vaccinations into low-income countries through partnerships between countries, donors, academia, international organizations and industry. GAVI continues this work and as of March 2013, 25 GAVI-eligible and supported countries have introduced the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Further, 15 additional GAVI countries have plans to introduce the vaccine into their national immunization program and 23 additional countries have approved GAVI support to introduce the vaccine.[21]

Side effects

Local reactions such as pain, swelling, or redness occur in up to 50% of those vaccinated with PCV13; of these, 8% are considered severe. Local reactions are more likely after the 4th dose than the earlier doses.[22] In clinical trials, fever greater than 100.4 F (38 C) was reported at a rate of 24-35% following any dose in the primary series and nonspecific symptoms such as decreased appetite or irritability occur in up to 80% of recipients.[22] In a vaccine safety datalink study, febrile seizures occurred in roughly 1 in 83,000 to 1 in 6,000 children given PCV 13, and 1 in 21,000 to 1 in 2,000 of those who were given PCV13 and trivalent influenza vaccine at the same time.[22]

Types

Pneumosil

Pneumosil is a decavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine produced by the Serum Institute of India. It contains the serotypes 1, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 19A, 19F, and 23F, and was prequalified by WHO in January 2020.[23][24]

Prevnar

Prevnar 13 (PCV13) is produced by Pfizer (formerly Wyeth) and replaced Prevnar. It is a tridecavalent vaccine, it contains thirteen serotypes of pneumococcus (1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, and 23F) which are conjugated to diphtheria carrier protein.[25][1] Prevnar 13 was approved for use in the European Union in December 2009.[7] On February 2010, Prevnar 13 was approved in the United States to replace the pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate vaccine.[26][27] After waiting for the outcome of a trial underway in the Netherlands, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended the vaccine for adults over age 65 in August 2014.[28]

Prevnar (PCV7) was a heptavalent vaccine, meaning that it contains the cell capsule sugars of seven serotypes of the bacteria S. pneumoniae (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F), conjugated with diphtheria proteins. It was manufactured by Wyeth (which was acquired by Pfizer).[29] Prevnar was approved for use in the United States in February 2000,[30] and vaccination with Prevnar was recommended for all children younger than two years, and for unvaccinated children between 24 and 59 months old who were at high risk for pneumococcal infections.[31]

Prevnar was produced from the seven most prevalent strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria in the U.S. The bacterial capsule sugars, a characteristic of these pathogens, are linked to CRM197, a nontoxic recombinant variant of diphtheria toxin (Corynebacterium diphtheriae).

The vaccine's polysaccharide sugars are grown separately in soy peptone broths. Through reductive amination, the sugars are directly conjugated to the protein carrier CRM197 to form the glycoconjugate. CRM197 is grown in C. diphtheriae strain C7 in a medium of casamino acids and yeast extracts.[32]

The original seven-valent formulation contained serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F, and resulted in a 98% probability of protection against these strains, which caused 80% of the pneumococcal disease in infants in the U.S. PCV7 is no longer produced.[33]

In 2010, Pfizer introduced Prevnar 13, which contains six additional strains (1, 3, 5, 6A, 19A and 7F), which protect against the majority of the remaining pneumococcal infections.[34]

On 10 June 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Prevnar 20, a 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, which includes the serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 8, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F,14, 15B, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F, and 33F, for adults 18 years of age and older.[35][2]

Synflorix

Synflorix (PCV10) is produced by GlaxoSmithKline. It is a decavalent vaccine, it contains ten serotypes of pneumococcus (1, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) which are conjugated to a carrier protein. Synflorix received a positive opinion from the European Medicines Agency for use in the European Union in January 2009[36] and GSK received European Commission authorization to market Synflorix in March 2009.[37][4]

A pentadecavalent vaccine candidate, PCV15 with serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, 19A, 22F, 23F, and 33F, has been developed by GlaxoSmithKline and was moved to Phase III clinical trial in 2018.[38]

Vaxneuvance

Vaxneuvance is a pneumococcal 15-valent conjugate vaccine that was approved for medical use in the United States in July 2021.[3][39] Vaxneuvance is indicated for the active immunization for the prevention of invasive disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F in adults 18 years of age and older.[3][39][40]

On 14 October 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Vaxneuvance, intended for prophylaxis against pneumococcal pneumonia and associated invasive disease.[41] The applicant for this medicinal product is Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V.[41]

Schedule of vaccination

As with all immunizations, whether it is available or required, and under what circumstances, varies according to the decisions made by local public health agencies.

Children under the age of two years fail to mount an adequate response to the 23-valent adult vaccine, and so a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is used. While this covers only seven strains out of more than ninety strains, these seven strains cause 80% to 90% of cases of severe pneumococcal disease, and it is considered to be nearly 100% effective against these strains.[42]

United Kingdom

The UK childhood vaccination schedule for infants born after 31 December 2019, consists of a primary course of one dose at twelve weeks of age with a second dose at one year of age.[43][44] For infants born before 1 January 2020 and those in Scotland, the childhood vaccination schedule consists of a primary course of two doses at eight and sixteen weeks of age with a final third dose at one year of age.[44][45]

Children at special risk (e.g., sickle cell disease and asplenia) require as full protection as can be achieved using the conjugated vaccine, with the more extensive polysaccharide vaccine given after the second year of life:[44]

| Age | 2–6 months | 7–11 months | 12–23 months |

| Conjugated vaccine | 3 × monthly dose | 2 × monthly dose | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

| Further dose in second year of life | |||

| 23-valent vaccine | Then after 2nd birthday single dose of 23-valent | ||

United States

In 2001, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), upon advice from its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), recommended the vaccine be administered to every infant and young child in the United States. The resulting demand outstripped production, creating shortages not resolved until 2004. All children, according to the U.S. vaccination schedule, should receive four doses, at two months, four months, six months, and again between one year and fifteen months of age.[46][47]

The CDC updated the pneumococcal vaccine guidelines for adults 65 years of age or older in 2019.[48]

In October 2021, the CDC recommended that adults 65 years of age or older who have not previously received a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine or whose previous vaccination history is unknown should receive a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (either PCV20 or PCV15).[49] If PCV15 is used, this should be followed by a dose of PPSV23.[49] The CDC recommended that adults aged 19 to 64 years with certain underlying medical conditions or other risk factors who have not previously received a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine or whose previous vaccination history is unknown should receive a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (either PCV20 or PCV15).[49] If PCV15 is used, this should be followed by a dose of PPSV23.[49]

Society and culture

Legal status

On 16 December 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Apexxnar, intended for prophylaxis against pneumococcal pneumonia and associated invasive disease.[50] The applicant for this medicinal product is Pfizer Europe MA EEIG.[50]

Economics

Prevnar 13 is Pfizer's best-selling product.[51] It had annual sales of US$5.85 billion in 2020.[51][52]

Brand names

The vaccines are marketed under several brand names including Prevnar 20,[2] Prevnar 13,[1] Synflorix,[7][4] Pneumosil, and Vaxneuvance.[3][39]

References

- 1 2 3 "Prevnar 13- pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine injection, suspension". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Prevnar 20- pneumococcal 20-valent conjugate vaccine injection, suspension". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vaxneuvance- pneumococcal 15-valent conjugate vaccine crm197 protein adsorbed injection, suspension". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Synflorix EPAR". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 8 January 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 World Health Organization (2019). "Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in infants and children under 5 years of age: WHO position paper –February 2019". Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 94 (8): 85–104. hdl:10665/310970.

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/who_pp_pcv_2019_summary.pdf.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/who_pp_pcv_2019_summary.pdf.

- ↑ Dagan, Ron; Ben-Shimol, Shalom (2021). "21. Pneumococcal vaccine". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 223–248. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Prevenar 13 EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 26 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2020. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ Hervé C, Laupèze B, et al. (2019). "The how's and what's of vaccine reactogenicity". NPJ Vaccines. 4 (39): 39. doi:10.1038/s41541-019-0132-6. PMC 6760227. PMID 31583123.

- ↑ "CDC - ABCs: Surveillance Reports main page - Active Bacterial Core surveillance". 19 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Arthur (21 June 2007). "What if a vaccine makes room for a new strain of a disease?". Slate.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. (May 2003). "Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (18): 1737–46. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022823. PMID 12724479.

- ↑ Poehling KA, Talbot TR, Griffin MR, et al. (April 2006). "Invasive pneumococcal disease among infants before and after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 295 (14): 1668–74. doi:10.1001/jama.295.14.1668. PMID 16609088.

- ↑ Whitney CG, Pilishvili T, Farley MM, et al. (October 2006). "Effectiveness of seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease: a matched case-control study". Lancet. 368 (9546): 1495–502. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69637-2. PMID 17071283. S2CID 11834808. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Millar EV, Watt JP, Bronsdon MA, et al. (2008). "Indirect effect of 7‐valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal colonization among unvaccinated household members". Clin Infect Dis. 47 (8): 989–996. doi:10.1086/591966. PMID 18781875.

- ↑ Siemieniuk, Reed A.C.; Gregson, Dan B.; Gill, M. John (November 2011). "The persisting burden of invasive pneumococcal disease in HIV patients: an observational cohort study". BMC Infectious Diseases. 11: 314. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-314. PMC 3226630. PMID 22078162.

- ↑ Barocchi MA, Censini S, Rappuoli R (2007). "Vaccines in the era of genomics: the pneumococcal challenge". Vaccine. 25 (16): 2963–73. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.065. PMID 17324490.

- ↑ Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Arbogast PG, Martin SW, Edwards KM, Griffin MR (April 2007). "Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis". Lancet. 369 (9568): 1179–86. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60564-9. PMID 17416262. S2CID 26494828.

- 1 2 Tsai CJ, Griffin MR, Nuorti JP, Grijalva CG (June 2008). "Changing epidemiology of pneumococcal meningitis after the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the United States". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (11): 1664–72. doi:10.1086/587897. PMC 4822508. PMID 18433334.

- 1 2 O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. (2009). "Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates". Lancet. 374 (9693): 893–902. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. PMID 19748398. S2CID 18964449.

- ↑ "PneumoADIP - Need for PneumoADIP". Pneumoasdip.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, International Vaccine Access Center (2013). "VIMS Report: Global vaccine introduction" (PDF). Jhsph.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Gierke R, Wodi P, Kobayashi M, Hall E, Hamborsky J. "Pinkbook Pneumococcal Epidemiology of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ "Gavi-supported pneumococcal conjugate vaccines profiles to support country decision making" (PDF). GAVI. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ↑ "Pneumosil, the new pneumococcal vaccine, achieves WHO prequalification, a key step toward improving access and affordability" (Press release). Serum Institute of India. PR Newswire. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ↑ "Prevnar 13". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 March 2018. STN 125324. Archived from the original on 27 November 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "FDA Approves Pneumococcal Disease Vaccine with Broader Protection" (Press release). Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Prevnar 13". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 March 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Votes to Recommend Pfizer's Prevnar 13 Vaccine in Adults Aged 65 Years and Older". MarketWatch.com. 13 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "Pneumococcal 7-valent Conjugate Vaccine (Diphtheria CRM197 Protein)". Wyeth. 2006. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006.

- ↑ "February 17, 2000 Approval Letter". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 10 July 2009.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Infectious Diseases. Policy statement: recommendations for the prevention of pneumococcal infections, including the use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar), pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, and antibiotic prophylaxis". Pediatrics. 106 (2 Pt 1): 362–6. 2000. doi:10.1542/peds.106.2.362. PMID 10920169.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "WHO SAGE evidence to recommendations table" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (March 2010). "Licensure of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and recommendations for use among children — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59 (9): 258–61. PMID 20224542. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ "Prevnar 20". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "EMEA Document" (PDF). Emea.europa.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "GSK Release". Gsk.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "Merck Announces First Phase Three Studies for PCV-15 (V114) Its Investigational Pneumococcal Disease Vaccine" (Press release). 17 April 2018. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Vaxneuvance". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 July 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Merck Announces U.S. FDA Approval of Vaxneuvance (Pneumococcal 15-valent Conjugate Vaccine) for the Prevention of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Adults 18 Years and Older Caused by 15 Serotypes" (Press release). Merck. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021 – via Business Wire.

- 1 2 "Vaxneuvance: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency. 13 October 2021. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ Childhood Pneumococcal Disease Childhood Pneumococcal Disease : Immunisation - Victorian Government Health Information, Australia at the Wayback Machine (archived 25 October 2006) - information on the disease and the Prevnar vaccine, from the Victoria State (Australia) government. Includes possible side effects.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 4 Ramsay M, ed. (January 2020). "Chapter 25: Pneumococcal". Immunisation against infectious disease. Public Health England. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ "Archive copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule for ages 18 years or younger, United States, 2019". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 February 2019. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ↑ Nuorti JP, Whitney CG (December 2010). "Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children - use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine - recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 59 (RR-11): 1–18. PMID 21150868. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, Kobayashi M, Leidner A, Pilishvili T (November 2019). "Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices" (PDF). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 68 (46): 1069–1075. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a5. PMC 6871896. PMID 31751323. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "ACIP Vaccine Recommendations and Schedules". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 "Apexxnar: Pending EC decision". European Medicines Agency. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- 1 2 "Pfizer Inc. 2020 Form 10-K Annual Report" (PDF). Pfizer. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Herper, Matthew (24 August 2020). "In the race for a Covid-19 vaccine, Pfizer turns to a scientist with a history of defying skeptics — and getting results". Stat News. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

Further reading

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015). "Chapter 17: Pneumococcal Disease". In Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S (eds.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "13-Valent Pneumococcal Vaccine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "Heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- "Pneumococcal Conjugate (PCV13) Vaccine Information Statement". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 August 2021. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2021.