Sézary syndrome

| Sézary disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Sézary's disease, Sézary syndrome[1] | |

| |

| The bright red rash of Sezary syndrome | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Oncology, dermatology |

| Symptoms |

|

| Prognosis | Poor[3] |

| Frequency | Rare, age > 60, males>females[2] |

Sézary syndrome (SS), is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), characterised by redness of skin, general swollen lymph glands and abnormal T-cells, known as Sézary's cells.[2]

Although considered related to mycosis fungoides (MF), both are distinct entities due to their cell of origin and behaviour.[2] If extreme redness of skin and blood involvement occurs in a person with classic MF, the diagnosis maybe considered as 'SS preceded by MF' or 'secondary erythrodermic CTCL'.[3]

It accounts for around 2% to 3% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas.[3] It was first described by Albert Sézary.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Sézary disease and mycosis fungoides are cutaneous T-cell lymphomas having a primary manifestation in the skin.[5] The disease's origin is a peripheral CD4+ T-lymphocyte,[6] although rarer CD8+/CD4- cases have been observed.[6] Epidermotropism (lymphocytes residing in the epidermis)[7] by neoplastic CD4+ lymphocytes with the formation of Pautrier's microabscesses is the hallmark sign of the disease. Although the condition can affect people of all ages, it is commonly diagnosed in adults over age 60.[8][6] The dominant signs and symptoms of the disease are:

- Generalized erythroderma– redness of the skin[6]

- Lymphadenopathy – swollen, enlarged lymph nodes[6]

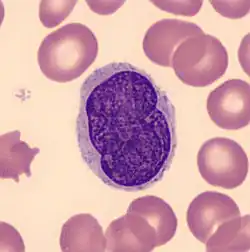

- Atypical T-cells – malignant lymphocytes known as "Sézary cells" seen in the peripheral blood with typical cerebriform nuclei (brain-shaped, convoluted nuclei)[9][6]

- Hepatosplenomegaly– enlarged liver and spleen[10]

- Palmoplantar keratoderma – thickening of the palms of the hands, and soles of the feet[11][12]

.jpg.webp) Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome.jpg.webp) Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome.jpg.webp) Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome.jpg.webp) Sézary syndrome

Sézary syndrome

Diagnosis

Those who have Sézary disease often present with skin lesions that do not heal with normal medication.[13] A blood test generally reveals any change in the levels of lymphocytes in the blood, which is often associated with a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[13] Finally, a biopsy of a skin lesion can be performed to rule out any other causes.[13]

The immunohistochemical features are very similar to those presented in mycosis fungoides except for the following differences:[14]

- More monotonous cellular infiltrates (large, clustered atypical pagetoid cells) in Sézary syndrome

- Sometimes absent epidermotropism

- Increased lymph node involvement with infiltrates of Sézary syndrome.

Sézary cell: pleomorphic abnormal T cell with the characteristic cerebriform nuclei (Peripheral blood - MGG stain).

Sézary cell: pleomorphic abnormal T cell with the characteristic cerebriform nuclei (Peripheral blood - MGG stain). Sézary syndrome in a 61-year-old man presenting in 1972 with unrelenting itchiness of six months’ duration. On the right is his peripheral blood film stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) showing a neoplastic T cell (Sézary cell).

Sézary syndrome in a 61-year-old man presenting in 1972 with unrelenting itchiness of six months’ duration. On the right is his peripheral blood film stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) showing a neoplastic T cell (Sézary cell).

Treatment

Treatment typically includes some combination of photodynamic therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and biologic therapy.[15]

Treatments are often used in combination with phototherapy and chemotherapy, though pure chemotherapy is rarely used today.[6] No single treatment type has revealed clear-cut benefits in comparison to others, treatment for all cases remains problematic.[16]

Radiation

A number of types of radiation therapy may be used including total skin electron therapy.[17] While this therapy does not generally result in systemic toxic effects it can produce side effects involving the skin.[17] It is only available at a few institutions.[17]

Chemotherapy

Romidepsin, vorinostat and a few others are a second-line drug for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[18] Mogamulizumab has been approved in Japan and the United States.[19]

Epidemiology

In the Western population, there are around 3 cases of Sézary syndrome per 1,000,000 people.[6] Sézary disease is more common in males with a ratio of 2:1,[6] and the mean age of diagnosis is between 55 and 60 years of age.[6][10]

See also

References

- ↑ Reference, Genetics Home. "Sézary syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DE, Elder; D, Massi; RA, Scolyer; R, Willemze (2018). "Tumors of haemopoietic and lymphoid origin: Sézary disease". WHO Classification of Skin Tumours. Vol. 11 (4th ed.). Lyon (France): World Health Organization. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-92-832-2440-2. Archived from the original on 2022-07-11. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- 1 2 3 García-Díaz, Nuria; Piris, Miguel Ángel; Ortiz-Romero, Pablo Luis; Vaqué, José Pedro (16 April 2021). "Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome: An Integrative Review of the Pathophysiology, Molecular Drivers, and Targeted Therapy". Cancers. 13 (8): 1931. doi:10.3390/cancers13081931. ISSN 2072-6694. PMID 33923722. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ Sézary's cell at Who Named It?

- ↑ Cerroni, Lorenzo; Kevin Gatter; Helmut Kerl (2005). An illustrated guide to Skin Lymphomas. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4051-1376-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cuneo, A; Castoldi, GL (2005). "Mycosis fungoidses/Sezary's syndrome". Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol. 9 (3): 242–243. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Mutasim, Diya F. (2015). "What Is Dermatitis with Epidermotropism?". Practical Skin Pathology. Springer International Publishing. pp. 37–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-14729-1_8. ISBN 978-3-319-14728-4.

- ↑ "Sezary syndrome". genetic and rare diseases information center. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Park, HS; McIntosh, L; Braschi-Amirfarzan, M; Shinagare, AB; Krajewski, KM (January 2017). "T-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas: Spectrum of Disease and the Role of Imaging in the Management of Common Subtypes". Korean Journal of Radiology. 18 (1): 71–83. doi:10.3348/kjr.2017.18.1.71. PMC 5240486. PMID 28096719.

- 1 2 Lorincz, A. I. "Sezary syndrome". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Fragkos, Konstantinos C. (2017). "Plantar keratoderma of Sézary syndrome". Clinical Case Reports. 5 (10): 1726–1727. doi:10.1002/ccr3.1168. ISSN 2050-0904. PMC 5628207. PMID 29026585.

- ↑ Martin, Stephanie J.; Duvic, Madeleine (2012-10-01). "Prevalence and treatment of palmoplantar keratoderma and tinea pedis in patients with Sézary syndrome". International Journal of Dermatology. 51 (10): 1195–1198. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05204.x. ISSN 1365-4632. PMID 22994666.

- 1 2 3 "Diagnosis". Archived from the original on 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Beigi, Pooya Khan Mohammad (2017). "Diagnosis and Management". Clinician's Guide to Mycosis Fungoides. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. Vol. 35. Springer International Publishing. pp. 13–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47907-1_4. ISBN 9783319479064. PMC 1806090. PMID 13618707.

- ↑ "Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 7 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Cerroni, Lorenzo; Kevin Gatter; Helmut Kerl (2005). An illustrated guide to Skin Lymphomas. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4051-1376-2.

- 1 2 3 "Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 12 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Jawed, SI; Myskowski, PL; Horwitz, S; Moskowitz, A; Querfeld, C (February 2014). "Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 70 (2): 223.e1–17, quiz 240–2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.033. PMID 24438970.

- ↑ "FDA approves mogamulizumab-kpkc for mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2018-08-08. Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Illustration of Sezary cells Archived 2011-06-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Sezary Syndrome lymphoma information Archived 2021-01-15 at the Wayback Machine