Eurovision Song Contest 1993

The Eurovision Song Contest 1993 was the 38th edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, held on 15 May 1993 at the Green Glens Arena in Millstreet, Ireland. Organised by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) and host broadcaster Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ), and presented by Fionnuala Sweeney, the contest was held in Ireland following the country's victory at the 1992 contest with the song "Why Me?" by Linda Martin.

| Eurovision Song Contest 1993 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dates | |

| Final | 15 May 1993 |

| Host | |

| Venue | Green Glens Arena, Millstreet, Ireland |

| Presenter(s) | Fionnuala Sweeney |

| Musical director | Noel Kelehan |

| Directed by | Anita Notaro |

| Executive supervisor | Christian Clausen |

| Executive producer | Liam Miller |

| Host broadcaster | Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ) |

| Website | eurovision |

| Participants | |

| Number of entries | 25 |

| Debuting countries | |

| Returning countries | None |

| Non-returning countries | |

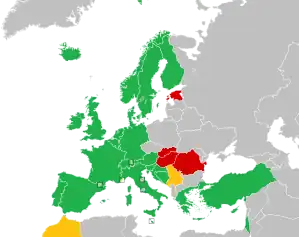

Participation map

| |

| Vote | |

| Voting system | Each country awarded 12, 10, 8–1 point(s) to their 10 favourite songs |

| Winning song | "In Your Eyes" |

Twenty-five countries participated in the contest – the largest event yet held. Twenty-two of the twenty-three countries which had participated in the previous year's event returned, with Yugoslavia prevented from competing following the closure of its national broadcaster and the placement of sanctions against the country as a response to the Yugoslav Wars. In response to an increased interest in participation from former Eastern Bloc countries following the collapse of communist regimes, three spaces in the event were allocated to first-time participating countries, which would be determined through a qualifying competition. Held in April 1993 in Ljubljana, Slovenia, Kvalifikacija za Millstreet featured entries from seven countries and resulted in the entries from the former Yugoslav republics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia progressing to the contest in Millstreet.

For the second year in a row the winner was Ireland with the song "In Your Eyes", written by Jimmy Walsh and performed by Niamh Kavanagh. The United Kingdom, Switzerland, France, and Norway completed the top five, with the United Kingdom achieving their second consecutive runner-up placing. Ireland achieved their fifth victory in the contest, matching the overall record held by France and Luxembourg, and joined Israel, Luxembourg and Spain as countries with wins in successive contests.

Location

The 1993 contest took place in Millstreet, Ireland, following the country's victory at the 1992 edition with the song "Why Me?", performed by Linda Martin. It was the fourth time that Ireland had hosted the contest, having previously staged the event in 1971, 1981 and 1988, with all previous events held in the country's capital city Dublin.[1][2]

The Green Glens Arena, an indoor arena used primarily for equestrian events, was chosen as the contest venue, with its owner Noel C Duggan offering the use of the venue for free, as well as pledging a further £200,000 from local businesses for the staging of the event.[3][4] Individuals within RTÉ, including the organisation's Director-General Joe Barry, were interested in staging the event outside of Dublin for the first time, and alongside Dublin RTÉ production teams scouted locations in rural Ireland in the months following Ireland's win.[5] Although the contest had previously been held in smaller towns, such as Harrogate, a English town of 70,000 people which staged the 1982 contest, with a population of 1,500 Millstreet became the smallest settlement to stage the event at that time and continues to hold the record as of 2023.[6] The arena would have an audience of around 3,500 during the contest.[3] The choice of Millstreet and the Green Glens Arena to stage the contest was met with some ridicule, with BBC journalist Nicholas Witchell referring to the venue as a "cowshed", however Millstreet had won out over more conventional locations, including Dublin and Galway, due to the facilities available in the Green Glens Arena and the town's local community which were hugely enthusiastic about the event being staged in their area.[6][5][7]

Due to the small size of Millstreet, delegations were primarily based in surrounding settlements, including Killarney and other towns in counties Cork and Kerry.[5][8] Alongside Millstreet itself, Killarney and Cork City held receptions for the competing delegates during the week of the contest, at the Great Southern Hotel in Killarney and Cork's City Hall, the latter hosted by the Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht.[9]

Participating countries

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the Eurovision Song Contest regularly featured over twenty participating countries in each edition, and by 1992 an increasing number of countries had begun expressing an interested in joining the event for the first time. This came as a result of revolutions among many European countries that led to the fall of communist regimes and the formation of liberal democratic government among existing states and newly sovereign countries formed from entities within the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.[1][10] In an effort to incorporate these new countries into the contest, the contest organisers the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) raised the maximum number of participating countries to twenty-five – the highest number yet seen in the contest – creating space for three new countries to participate alongside twenty-two of the twenty-three countries which had participated in the 1992 contest.[4][10] Yugoslavia – which had participated in the contest since 1961[lower-alpha 1] – was unable to participate as its EBU member broadcaster Jugoslovenska radiotelevizija (JRT) was disbanded in 1992 and its successor organisations Radio-televizija Srbije (RTS) and Radio-televizija Crne Gore (RTCG) were barred from joining the EBU due to sanctions against the country as part of the Yugoslav Wars.[4][12]

As a temporary solution for the 1993 contest, a qualifying round was organised to determine the three countries which would join the contest for the first time. Subsequently, for the 1994 contest, a relegation system was introduced which would bar the lowest-scoring countries from participating in the following year's event.[1][4][10] At the running order draw, held in December 1992 at the National Concert Hall in Dublin and hosted by Pat Kenny and Linda Martin, the three new countries were represented as Countries A, B and C, corresponding with the countries that placed first, second and third in the qualifying competition respectively.[10][13] Entitled Kvalifikacija za Millstreet, the qualifying round took place on 3 April 1993 in Ljubljana, Slovenia.[1][10] Initially broadcasters in as many as fourteen countries registered an interest in competing in the event, however only seven countries eventually submitted entries, representing Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.[10] Ultimately the entries from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia were chosen to progress to the contest proper in Millstreet;[1][4][10] as constituent republics of SFR Yugoslavia, representatives from all three countries had previously competed in the contest.[14]

The contest featured three artists who had previously participated in the contest: Tony Wegas represented Austria for a second consecutive year; Katri Helena made a second appearance for Finland, having previously competed in 1979; and Denmark's Tommy Seebach, having previously competed in 1979 as a solo artist and in 1981 alongside Debbie Cameron, competed in the 1993 contest as part of the Seebach Band.[15]

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) | Conductor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | Tony Wegas | "Maria Magdalena" | German |

|

Christian Kolonovits | |

| BRTN | Barbara | "Iemand als jij" | Dutch |

|

Bert Candries | |

| RTVBiH | Fazla | "Sva bol svijeta" | Bosnian | Noel Kelehan[lower-alpha 2] | ||

| HRT | Put | "Don't Ever Cry" | Croatian, English |

|

Andrej Baša | |

| CyBC | Zymboulakis and Van Beke | "Mi stamatas" (Μη σταματάς) | Greek |

|

George Theofanous | |

| DR | Seebach Band | "Under stjernerne på himlen" | Danish | George Keller | ||

| YLE | Katri Helena | "Tule luo" | Finnish |

|

Olli Ahvenlahti | |

| France Télévision | Patrick Fiori | "Mama Corsica" | French, Corsican | François Valéry | Christian Cravero | |

| MDR[lower-alpha 3] | Münchener Freiheit | "Viel zu weit" | German | Stefan Zauner | Norbert Daum | |

| ERT | Katerina Garbi | "Ellada, hora tou fotos" (Ελλάδα, χώρα του φωτός) | Greek | Dimosthenis Stringlis | Haris Andreadis | |

| RÚV | Inga | "Þá veistu svarið" | Icelandic |

|

Jon Kjell Seljeseth | |

| RTÉ | Niamh Kavanagh | "In Your Eyes" | English | Jimmy Walsh | Noel Kelehan | |

| IBA | Lehakat Shiru | "Shiru" (שירו) | Hebrew, English |

|

Amir Frohlich | |

| RAI | Enrico Ruggeri | "Sole d'Europa" | Italian | Enrico Ruggeri | Vittorio Cosma | |

| CLT | Modern Times | "Donne-moi une chance" | French, Luxembourgish |

|

Francis Goya | |

| PBS | William Mangion | "This Time" | English | William Mangion | Joseph Sammut | |

| NOS | Ruth Jacott | "Vrede" | Dutch | Harry van Hoof | ||

| NRK | Silje Vige | "Alle mine tankar" | Norwegian | Bjørn Erik Vige | Rolf Løvland | |

| RTP | Anabela | "A cidade até ser dia" | Portuguese |

|

Armindo Neves | |

| RTVSLO | 1X Band | "Tih deževen dan" | Slovene |

|

Jože Privšek | |

| TVE | Eva Santamaría | "Hombres" | Spanish | Carlos Toro | Eduardo Leiva | |

| SVT | Arvingarna | "Eloise" | Swedish |

|

Curt-Eric Holmquist | |

| SRG SSR | Annie Cotton | "Moi, tout simplement" | French |

|

Marc Sorrentino | |

| TRT | Burak Aydos, Öztürk Baybora and Serter | "Esmer Yarim" | Turkish | Burak Aydos | No conductor | |

| BBC | Sonia | "Better the Devil You Know" | English |

|

Nigel Wright |

| Country | Broadcaster | Artist | Song | Language | Songwriter(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETV | Janika Sillamaa | "Muretut meelt ja südametuld" | Estonian |

| |

| MTV | Andrea Szulák | "Árva reggel" | Hungarian |

| |

| TVR | Dida Drăgan | "Nu pleca" | Romanian |

| |

| STV | Elán | "Amnestia na neveru" | Slovak |

|

Production and format

The Eurovision Song Contest 1993 was produced by the Irish public broadcaster Radio Telefís Éireann (RTÉ). Liam Miller served as executive producer, Kevin Linehan served as producer, Anita Notaro served as director, Alan Farquharson served as designer, and Noel Kelehan served as musical director, leading the RTÉ Concert Orchestra.[1][19][20][21] A separate musical director could be nominated by each country to lead the orchestra during their performance, with the host musical director also available to conduct for those countries which did not nominate their own conductor.[15]

Each participating broadcaster submitted one song, which was required to be no longer than three minutes in duration and performed in the language, or one of the languages, of the country which it represented.[22][23] A maximum of six performers were allowed on stage during each country's performance, and all participants were required to have reached the age of 16 in the year of the contest.[22][24] Each entry could utilise all or part of the live orchestra and could use instrumental-only backing tracks, however any backing tracks used could only include the sound of instruments featured on stage being mimed by the performers.[24][25]

The results of the 1993 contest were determined through the same scoring system as had first been introduced in 1975: each country awarded twelve points to its favourite entry, followed by ten points to its second favourite, and then awarded points in decreasing value from eight to one for the remaining songs which featured in the country's top ten, with countries unable to vote for their own entry.[26] The points awarded by each country were determined by an assembled jury of sixteen individuals, which was required to be split evenly between members of the public and music professionals, between men and women, and between those over and under 30 years of age. Each jury member voted in secret and awarded between one and ten votes to each participating song, excluding that from their own country and with no abstentions permitted. The votes of each member were collected following the country's performance and then tallied by the non-voting jury chairperson to determine the points to be awarded. In any cases where two or more songs in the top ten received the same number of votes, a show of hands by all jury members was used to determine the final placing.[27][28]

The 1993 contest was at the time the largest outside broadcast production ever undertaken by RTÉ, and the broadcaster was reported to have spent over £2,200,000 on producing the event.[29][30] In order to stage the event Millstreet and the Green Glens Arena underwent major infrastructure improvements, which were led by local groups and individuals.[5][29] The floor area within the arena had to be dug out in order to create additional height to facilitate the stage and equipment, extra phone lines had to be installed, and the town's railway line and station required an extension at an extra cost of over £1,000,000.[3][4][31]

The stage design for the Millstreet contest featured the largest stage yet constructed for the event, covering 2,500ft² (232m²) of translucent material which was illuminated from below by lighting strips. A mirror image of the triangular shaped stage was suspended from above, and a slanted background created a distorted perspective for the viewer. A hidden doorway featured in the centre of the stage, which was used by the presenter at the beginning of the show, and by the winning artist as they re-entered the arena following the broadcast.[4][30][32] The contest logo was designed by Conor Cassidy and was adapted from aspects of the coat of arms of County Cork.[30]

Contest overview

The contest took place on 15 May 1993 at 20:00 (IST) and lasted 3 hours and 1 minute.[1][15] The show was presented by the Irish journalist Fionnuala Sweeney.[1][33]

The contest was opened by an animated sequence designed by Gary Keenan and inspired by Celtic mythology, set to Irish traditional music by composers Ronan Johnston and Shea Fitzgerald and featuring uilleann pipes player Davy Spillane.[5][30][34] The interval act comprised performances by previous Eurovision winners Linda Martin, reprising her winning song from the previous year's contest "Why Me?", and Johnny Logan, performing the song "Voices (Are Calling)" with choirs from the Cork School of Music and local children of Millstreet.[34][35][36] The trophy awarded to the winners was crafted by Waterford Crystal and was presented by Linda Martin.[34][35]

The winner was Ireland represented by the song "In Your Eyes", written by Jimmy Walsh and performed by Niamh Kavanagh.[37] This marked Ireland's fifth contest win, putting them level with Luxembourg and France for the country with the most wins, and its second win in a row, matching the same feat previously achieved by Spain (1968 and 1969), Luxembourg (1972 and 1973) and Israel (1978 and 1979).[2][27] The United Kingdom finished in second place for the second year in a row, and for a record-extending fourteenth time overall.[27][38]

| R/O | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enrico Ruggeri | "Sole d'Europa" | 45 | 12 | |

| 2 | Burak Aydos, Öztürk Baybora and Serter | "Esmer Yarim" | 10 | 21 | |

| 3 | Münchener Freiheit | "Viel zu weit" | 18 | 18 | |

| 4 | Annie Cotton | "Moi, tout simplement" | 148 | 3 | |

| 5 | Seebach Band | "Under stjernerne på himlen" | 9 | 22 | |

| 6 | Katerina Garbi | "Ellada, hora tou fotos" | 64 | 9 | |

| 7 | Barbara | "Iemand als jij" | 3 | 25 | |

| 8 | William Mangion | "This Time" | 69 | 8 | |

| 9 | Inga | "Þá veistu svarið" | 42 | 13 | |

| 10 | Tony Wegas | "Maria Magdalena" | 32 | 14 | |

| 11 | Anabela | "A cidade até ser dia" | 60 | 10 | |

| 12 | Patrick Fiori | "Mama Corsica" | 121 | 4 | |

| 13 | Arvingarna | "Eloise" | 89 | 7 | |

| 14 | Niamh Kavanagh | "In Your Eyes" | 187 | 1 | |

| 15 | Modern Times | "Donne-moi une chance" | 11 | 20 | |

| 16 | 1X Band | "Tih deževen dan" | 9 | 22 | |

| 17 | Katri Helena | "Tule luo" | 20 | 17 | |

| 18 | Fazla | "Sva bol svijeta" | 27 | 16 | |

| 19 | Sonia | "Better the Devil You Know" | 164 | 2 | |

| 20 | Ruth Jacott | "Vrede" | 92 | 6 | |

| 21 | Put | "Don't Ever Cry" | 31 | 15 | |

| 22 | Eva Santamaría | "Hombres" | 58 | 11 | |

| 23 | Zymboulakis and Van Beke | "Mi stamatas" | 17 | 19 | |

| 24 | Lehakat Shiru | "Shiru" | 4 | 24 | |

| 25 | Silje Vige | "Alle mine tankar" | 120 | 5 |

Spokespersons

Each country nominated a spokesperson, connected to the contest venue via telephone lines and responsible for announcing, in English or French, the votes for their respective country.[22][40] Known spokespersons at the 1993 contest are listed below.

France – Olivier Minne[41]

France – Olivier Minne[41] Ireland – Eileen Dunne[42]

Ireland – Eileen Dunne[42] Malta – Kevin Drake[43]

Malta – Kevin Drake[43] Sweden – Gösta Hanson[44]

Sweden – Gösta Hanson[44] United Kingdom – Colin Berry[27]

United Kingdom – Colin Berry[27]

Detailed voting results

Jury voting was used to determine the points awarded by all countries.[27] The announcement of the results from each country was conducted in the order in which they performed, with the spokespersons announcing their country's points in English or French in ascending order. However, due to a technical problem with the telephone connection, Malta, which had been scheduled to be the eighth country to vote, was passed over and instead voted last.[27][34] The detailed breakdown of the points awarded by each country is listed in the tables below.

| Italy | 45 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 10 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | 18 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | 148 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 6 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Denmark | 9 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Greece | 64 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| Belgium | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Malta | 69 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||

| Iceland | 42 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Austria | 32 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | 60 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 5 | |||||||||||

| France | 121 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 6 | |||||||

| Sweden | 89 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| Ireland | 187 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 12 | |

| Luxembourg | 11 | 1 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slovenia | 9 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Finland | 20 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 27 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| United Kingdom | 164 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 8 | |||

| Netherlands | 92 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Croatia | 31 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spain | 58 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||||||

| Cyprus | 17 | 2 | 10 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Israel | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Norway | 120 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 8 | ||||||||||

12 points

The below table summarises how the maximum 12 points were awarded from one country to another. The winning country is shown in bold. Ireland received the maximum score of 12 points from seven of the voting countries, with the United Kingdom receiving four sets of 12 points, Norway and Switzerland receiving three sets of maximum scores each, France and Portugal two sets each, and Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Greece and the Netherlands each receiving one maximum score.[45][46]

| N. | Contestant | Nation(s) giving 12 points |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 1 | ||

Broadcasts

Each participating broadcaster was required to relay the contest via its networks. Non-participating EBU member broadcasters were also able to relay the contest as "passive participants". Broadcasters were able to send commentators to provide coverage of the contest in their own native language and to relay information about the artists and songs to their television viewers.[24] Known details on the broadcasts in each country, including the specific broadcasting stations and commentators are shown in the tables below.

| Country | Broadcaster | Channel(s) | Commentator(s) | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBS | SBS TV[lower-alpha 6] | [79] | ||

| ETV | [57] | |||

| MTV | MTV1 | István Vágó | [80] | |

| TVP | TVP1 | Artur Orzech and Maria Szabłowska | [81][82] | |

| RTR | RTR[lower-alpha 7] | [83] | ||

| STV | STV2[lower-alpha 8] | [84] | ||

Notes and references

Footnotes

- Yugoslavia's participants had represented the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1961 and 1991 and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1992.[11]

- The nominated conductor for Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sinan Alimanović, was unable to safely commute to the flight to Ireland due to the ongoing Bosnian War; the contest's musical director, Noel Kelehan, subsequently led the orchestra during the Bosnian entry.[15]

- On behalf of the German public broadcasting consortium ARD[18]

- Deferred broadcast at 23:05 CEST (21:05 UTC)[58][67]

- Deferred broadcast on RTP Internacional at 21:45 WEST (20:45 UTC)[58]

- Deferred broadcast on 16 May at 20:30 AEST (10:30 UTC)[79]

- Deferred broadcast at 23:30 MSD (19:30 UTC) [57][83]

- Deferred broadcast on 16 May at 21:35 CEST (20:35 UTC)[84]

References

- "Millstreet 1993 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- "Ireland – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. pp. 132–145. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- Knox, David Blake (2015). "15. The Cowshed in Cork". Ireland and the Eurovision: The Winners, the Losers and the Turkey. Stillorgan, Republic of Ireland: New Island Books. pp. 129–140. ISBN 978-1-84840-429-8.

- "Hosting Eurovision: A city in the spotlight". European Broadcasting Union. 30 July 2016. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Fitzpatrick, Richard (14 May 2013). "The Eurovision in Millstreet: Looking back 20 years on". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Bobé, Raúl; Aja, Javier (16 May 2021). "Millstreet, the town that saw its Eurovision dream come true". La Prensa Latina. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 132–135. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Escudero, Victor M. (17 September 2017). "Rock me baby! Looking back at Yugoslavia at Eurovision". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "RTS: "Evrosong" treba da bude mesto zajedništva naroda" [RTS: "Eurosong" should be a place of unity of the people] (in Serbian). Radio Television of Serbia. 14 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- Harding, Peter (December 1992). Linda Martin and Pat Kenny (1992) (Photograph). National Concert Hall, Dublin, Ireland. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- "Yugoslavia – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 137–143. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- "Participants of Millstreet 1993". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 23 March 2023. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- "1993 – 38th edition". diggiloo.net. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- "Alle deutschen ESC-Acts und ihre Titel" [All German ESC acts and their songs]. www.eurovision.de (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- Harding, Peter (May 1993). Eurovision Song Contest production team (1993) (Photograph). Green Glens Arena, Millstreet, Ireland. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- "How it works – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 18 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Jerusalem 1999 – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

For the first time since the 1970s participants were free to choose which language they performed in.

- "The Rules of the Contest". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Escudero, Victor M. (18 April 2020). "#EurovisionAgain travels back to Dublin 1997". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

The orchestra also saw their days numbered as, from 1997, full backing tracks were allowed without restriction, meaning that the songs could be accompanied by pre-recorded music instead of the live orchestra.

- "In a Nutshell – Eurovision Song Contest". European Broadcasting Union. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. pp. 143–145. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Roxburgh, Gordon (2020). Songs for Europe: The United Kingdom at the Eurovision Song Contest. Vol. Four: The 1990s. Prestatyn, United Kingdom: Telos Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-84583-163-9.

- Tarrant, John (11 May 2023). "Millstreet remembers when the Cork town hosted Eurovision in 1993". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Connolly, Colm; McSweeney, Tom (9 May 1993). Bringing Eurovision to Millstreet (News report). Millstreet, Ireland: RTÉ News. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- Ó Liatháin, Concubhar (11 May 2023). "The night Millstreet was the centre of Europe as Eurovision came to town". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- Model of Eurovision Song Contest stage set (1993) (Computer model). April 1993. Archived from the original on 24 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023 – via RTÉ Libraries and Archives.

- "Fionnuala Sweeney: The atmosphere in Millstreet was electric!". European Broadcasting Union. 12 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Eurovision Song Contest 1993 (Television programme). Millstreet, Ireland: Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 15 May 1993.

- O'Connor, John Kennedy (2010). The Eurovision Song Contest: The Official History (2nd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Carlton Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-84732-521-1.

- "Johnny Logan: What the original double winner did next". European Broadcasting Union. 14 September 2023. Archived from the original on 18 September 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Niamh Kavanagh – Ireland – Millstreet". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- "United Kingdom – Participation history". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- "Final of Millstreet 1993". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- "Lugano to Liverpool: Broadcasting Eurovision". National Science and Media Museum. 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- "Introducing Hosts: Carla, Élodie Gossuin and Olivier Minne". European Broadcasting Union. 18 December 2021. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

Olivier is no stranger to the Eurovision family, too, having presented the French votes in 1992 and 1993, as well as providing broadcast commentary from 1995 through 1997.

- O'Loughlin, Mikie (8 June 2021). "RTE Eileen Dunne's marriage to soap star Macdara O'Fatharta, their wedding day and grown up son Cormac". RSVP Live. Reach plc. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- "Malta eighth in Eurovision contest". Times of Malta. 16 May 1993. p. 1.

- Thorsson, Leif; Verhage, Martin (2006). Melodifestivalen genom tiderna : de svenska uttagningarna och internationella finalerna (in Swedish). Stockholm: Premium Publishing. pp. 236–237. ISBN 91-89136-29-2.

- "Results of the Final of Millstreet 1993". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- "Eurovision Song Contest 1993 – Scoreboard". European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- "Fernsehen" [Television]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). 15 May 1993. pp. 27, 30. Retrieved 26 October 2022 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- Halbhuber, Axel (22 May 2015). "Ein virtueller Disput der ESC-Kommentatoren" [A virtual dispute between Eurovision commentators]. Kurier (in German). Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- "Programma's RTV Zaterdag" [Radio TV programmes on Saturday]. Leidsch Dagblad (in Dutch). 15 May 1993. p. 8. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Smolders, Thomas (8 April 2014). "VRT schuift André Vermeulen opzij bij Eurovisiesongfestival" [VRT pushes André Vermeulen aside at the Eurovision Song Contest]. De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- "Televisie en radio zaterdag" [Television and radio on Saturday]. Limburgs Dagblad (in Dutch). Heerlen, Netherlands. 15 May 1993. p. 46. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Delpher.

- "rtv – vrijeme" [radio TV – weather]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Split, Croatia. 15 May 1993. p. 55. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- Šćepanović, I. (6 May 1993). "Spremni za Millstreet" [Ready for Millstreet]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian). Split, Croatia. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- Karnakis, Kostas (24 February 2019). "H Eυριδίκη επιστρέφει στην... Eurovision! Όλες οι λεπτομέρειες... trans-title=Evridiki returns to... Eurovision! All the details..." AlphaNews (in Greek). Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - "Programoversigt – 15/05/1993" [Program overview – 15/05/1993] (in Danish). LARM.fm. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "Televisio & Radio" [Television & Radio]. Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 15 May 1993. pp. D17–D18. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Televisiooni nädalakava 10. mai – 16. mai" [Television weekly schedule 10th May – 16th May]. Päevaleht (in Estonian). 10 May 1993. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 28 October 2022 – via DIGAR Eesti artiklid.

- "Programmes TV – samedi 15 mai" [TV programmes – Saturday 15 May]. TV8 (in French). Cheseaux-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland: Ringier. 13 May 1993. pp. 10–15. Retrieved 26 October 2022 – via Scriptorium Digital Library.

- "Jan Hofer sagt "Tschau" zur Tagesschau" [Jan Hofer says "goodbye" to the Tagesschau]. egoFM (in German). 14 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- "Το πρόγραμμα της τηλεόρασης" [TV schedule] (PDF). Imerisia (in Greek). 15 May 1993. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Public Central Library of Veria.

- "Eurovision 2020: Γιώργος Καπουτζίδης -Μαρία Κοζάκου στον σχολιασμό του διαγωνισμού για την ΕΡΤ" [Eurovision 2020: Giorgos Kapoutzidis and Maria Kozakou to comment on the contest for ERT] (in Greek). Matrix24. 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- "Útvarp sjónvarp – laugurdagur 15. mai" [Radio television – Saturday 15 May]. DV (in Icelandic). 13 May 1995. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Timarit.is.

- "Saturday's Television". The Irish Times Weekend. 15 May 1993. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Walsh, Niamh (3 September 2017). "Pat Kenny: 'As Long As People Still Want Me I'll Keep Coming To Work'". evoke.ie. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- "Radio Highlights". The Irish Times Weekend. 15 May 1993. p. 6. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- "שבת 15.5 – טלוויזיה" [Saturday 15.5 – TV]. Hadashot (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv, Israel. 14 May 1993. p. 156. Retrieved 22 May 2023 – via National Library of Israel.

- "I programmi di oggi" [Today's programmes]. La Stampa (in Italian). 15 May 1993. p. 21. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "Ettore Andenna: «All'Eurovision meglio una classifica reale, non un voto popolare»" [Ettore Andenna: "At Eurovision a real ranking is better, not a popular vote"] (in Italian). Radio Number One. 18 May 2022. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Television". Times of Malta. 15 May 1993. p. 22.

- "Radio og TV – lørdag 15. mai" [Radio and TV – Saturday 15th May]. Moss Avis (in Norwegian). 15 May 1993. p. 37. Retrieved 26 October 2022 – via National Library of Norway.

- "P2 – Kjøreplan lørdag 15. mai 1993" [P2 – Schedule Saturday 15 May 1993] (in Norwegian). NRK. 30 April 1994. p. 17. Retrieved 4 November 2022 – via National Library of Norway. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- "Programa da televisão" [Television schedule]. A Comarca de Arganil (in Portuguese). 13 May 1993. p. 6. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "Spored za soboto" [Schedule for Saturday]. Delo: Sobotna priloga (in Slovenian). Ljubljana, Slovenia. 15 May 1993. p. 15. Retrieved 26 October 2023 – via Digital Library of Slovenia.

- "Televisión" [Television]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 15 May 1993. p. 6. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Albert, Antonio (15 May 1993). "Festival de Eurovisión" [Eurovision Destival]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- "L'Eurocanzone in cronaca diretta dall'Irlanda" [Eurovision live commentary from Ireland]. Giornale del Popolo (in Italian). Lugano, Switzerland. 15 May 1993. p. 31. Retrieved 12 December 2022 – via Sistema bibliotecario ticinese.

- "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC One". Radio Times. 15 May 1993. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- "Eurovision Song Contest – BBC Radio 2". Radio Times. 15 May 1993. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via BBC Genome Project.

- "Today's television". The Canberra Times. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 16 May 1993. p. 32. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via Trove.

- "TV – szombat május 15" [TV – Saturday 15 May]. Rádió és TeleVízió újság (in Hungarian). 10 May 1993. p. 46. Archived from the original on 23 July 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2022 – via MTVA Archívum.

- "Program telewizyjny" [Television programme]. Gazeta Jarocińska (in Polish). 14 May 1993. p. 22. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "Marek Sierocki i Aleksander Sikora skomentują Eurowizję! Co za duet!" [Marek Sierocki and Aleksander Sikora will comment on Eurovision! What a duo!]. pomponik.pl (in Polish). 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- "Неделя телевизионного экрана" [Weekly television screen] (PDF). Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian). 7 May 1993. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- "TV – Kűlfőldi műsorok – vasárnap május 16" [TV – Foreign programmes – Sunday 16th May]. Rádió és TeleVízió újság (in Hungarian). 10 May 1993. p. 57. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022 – via MTVA Archívum.