American Sign Language grammar

The grammar of American Sign Language (ASL) has rules just like any other sign language or spoken language. ASL grammar studies date back to William Stokoe in the 1960s.[1][2] This sign language consists of parameters that determine many other grammar rules. Typical word structure in ASL conforms to the SVO/OSV and topic-comment form, supplemented by a noun-adjective order and time-sequenced ordering of clauses. ASL has large CP and DP syntax systems, and also doesn't contain many conjunctions like some other languages do.

Morphology

ASL morphology consists of two different processes: derivational morphology and inflectional morphology.[3]

Derivational morphology in ASL occurs when movement in a sign changes the meaning - often between a noun and a verb.[4] For example, for the sign CHAIR, a noun, a person would tap their dominant pointer and middle fingers against their non-dominant pointer and middle fingers twice or more. For the sign SIT, a verb, a person would tap these fingers together only once and with more force.

Inflectional morphology adds units of language to other words.[3] For example, this would be changing 'watch' to 'watches' or 'watching.' In ASL, the sign may remain unchanged as WATCH, or the meaning may change based on NMM (Non-Manual-Markers).

ASL morphology is demonstrated with reduplication and indexicality as well.

Derivation

Compounding is used to derive new words in ASL, which often differ in meaning from their constituent signs.[5] For example, the signs FACE and STRONG compound to create a new sign FACE^STRONG, meaning 'to resemble'.[5] Compounds undergo the phonetic process of "hold deletion", whereby the holds at the end of the first constituent and the beginning of the second are elided:[5]

| Individual signs | Compound sign | |

|---|---|---|

| FACE | STRONG | FACE^STRONG |

| MH | HMH | MMH |

Many ASL nouns are derived from verbs.[6] This may be done either by reduplicating the movement of the verb if the verb has a single movement, or by restraining (making smaller and faster) the movement of the verb if it already has repeated movement.[7] For example, the noun CHAIR is derived from the verb SIT through reduplication.[7] Another productive method is available for deriving nouns from non-stative verbs.[8] This form of derivation modifies the verb's movement, reduplicating it in a "trilled" manner ("small, quick, stiff movements").[8] For example, this method is used to derive the noun ACTING from the verb ACT.[8]

Characteristic adjectives, which refer to inherent states, may be derived from adjectives which refer to "incidental or temporary states".[9] Characteristic adjectives always use both hands, even if the source adjective only uses one, and they always have repeated, circular movement.[9] Additionally, if the source adjective was one-handed, the derived adjective has alternating movement.[9] "Trilling" may also be used productively to derive adjectives with an "ish" meaning, e.g. BLUE becomes BLUISH.[10]

ASL occasionally uses suffixation in derivation, but less often than in English.[10] Agent nouns may be derived from verbs by adding the suffix AGENT and deleting the final hold of the verb, e.g. TEACH+AGENT 'teacher'.[10] Superlatives are also formed by suffixation, e.g. SMART+MOST 'smartest'.[11]

Certain types of signs, for example those relating to time and age, may incorporate numbers by assimilating their handshape.[11] For example, the word WEEK has handshape /B/ with the weak hand and /1/ with the active hand; the active hand's handshape may be changed to the handshape of any number up to 9 to indicate that many weeks.[11]

There are about 20 non-manual modifiers in ASL, which are either adjectival or adverbial.[12] For example, the adverb 'th', realized as the tongue being placed between the teeth, means 'carelessly / lazily' when combined with a verb:[13]

JOHN

WRITE

LETTER

'John writes a letter.'

JOHN

WRITE

th

LETTER

'John writes a letter carelessly.'

Degree

Mouthing is when an individual appears to be making speech sounds, and this is very important for fluent signing. It also has specific morphological uses. For example, one may sign 'man tall' to indicate the man is tall, but by mouthing the syllable cha while signing 'tall', the phrase becomes that man is enormous!

There are other ways of modifying a verb or adjective to make it more intense. These are all more or less equivalent to adding the word "very" in English; which morphology is used depends on the word being modified. Certain words which are short in English, such as 'sad' and 'mad', are sometimes fingerspelled rather than signed to mean 'very sad' and 'very mad'. However, the concept of 'very sad' or 'very mad' can be portrayed with the use of exaggerated body movements and facial expressions. Reduplication of the signs may also occur to emphasize the degree of the statement. Some signs are produced with an exaggeratedly large motion, so that they take up more sign space than normal. This may involve a back-and-forth scissoring motion of the arms to indicate that the sign ought to be yet larger, but that one is physically incapable of making it big enough. Many other signs are given a slow, tense production. The fact that this modulation is morphological rather than merely mimetic can be seen in the sign for 'fast': both 'very slow' and 'very fast' are signed by making the motion either unusually slowly or unusually quickly than it is in the citation forms of 'slow' and 'fast'—not exclusively by making it slower for 'very slow' and faster for 'very fast'.

Reduplication

Reduplication is morphological repetition, and this is extremely common in ASL. Generally the motion of the sign is shortened as well as repeated. Nouns may be derived from verbs through reduplication. For example, the noun chair is formed from the verb to sit by repeating it with a reduced degree of motion. Similar relationships exist between acquisition and to get, airplane and to fly (on an airplane), also window and to open/close a window. Reduplication is commonly used to express intensity as well as several verbal aspects (see below). It is also used to derive signs such as 'every two weeks' from 'two weeks', and is used for verbal number (see below), where the reduplication is iconic for the repetitive meaning of the sign.

Compounds

Many ASL words are historically compounds. However, the two elements of these signs have fused, with features being lost from one or both, to create what might be better called a blend than a compound. Typically only the final hold (see above) remains from the first element, and any reduplication is lost from the second.

An example is the verb AGREE, which derives from the two signs THINK and ALIKE. The verb THINK is signed by bringing a 1 hand inward and touching the forehead (a move and a hold). ALIKE is signed by holding two 1 hands parallel, pointing outward, and bringing them together two or three times. The compound/blend AGREE starts as THINK ends: with the index finger touching the forehead (the final hold of that sign). In addition, the weak hand is already in place, in anticipation of the next part of the sign. Then the hand at the forehead is brought down parallel to the weak hand; it approaches but does not make actual contact, and there is no repetition.

Affixes

ASL, like other mature signed languages, makes extensive use of morphology.[14] Many of ASL's affixes are combined simultaneously rather than sequentially. For example, Ted Supalla's seminal work on ASL verbs of motion revealed that these signs consist of many different affixes, articulated simultaneously according to complex grammatical constraints.[15] This differs from the concatenative morphology of many spoken languages, which except for suprasegmental features such as tone are tightly constrained by the sequential nature of voice sounds.

ASL does have a limited number of concatenative affixes. For example, the agentive suffix (similar to the English '-er') is made by placing two B or 5 hands in front of the torso, palms facing each other, and lowering them. On its own this sign means 'person'; in a compound sign following a verb, it is a suffix for the performer of the action, as in 'drive-er' and 'teach-er'. However, it cannot generally be used to translate English '-er', as it is used with a much more limited set of verbs. It is very similar to the '-ulo' suffix in Esperanto, meaning 'person' by itself and '-related person' when combined with other words.

An ASL prefix, (touching the chin), is used with number signs to indicate 'years old'. The prefix completely assimilates with the initial handshape of the number. For instance, 'fourteen' is signed with a B hand that bends several times at the knuckles. The chin-touch prefix in 'fourteen years old' is thus also made with a B hand. For 'three years old', however, the prefix is made with a 3 hand.

Numeral incorporation and classifiers

Rather than relying on sequential affixes, ASL makes heavy use of simultaneous modification of signs. One example of this is found in the aspectual system (see below); another is numeral incorporation: There are several families of two-handed signs which require one of the hands to take the handshape of a numeral. Many of these deal with time. For example, drawing the dominant hand lengthwise across the palm and fingers of a flat B hand indicates a number of weeks; the dominant hand takes the form of a numeral from one to nine to specify how many weeks. There are analogous signs for 'weeks ago' and 'weeks from now', etc., though in practice several of these signs are only found with the lower numerals.

ASL also has a system of classifiers which may be incorporated into signs.[16] A fist may represent an inactive object such as a rock (this is the default or neutral classifier), a horizontal ILY hand may represent an aircraft, a horizontal 3 hand (thumb pointing up and slightly forward) a motor vehicle, an upright G hand a person on foot, an upright V hand a pair of people on foot, and so on through higher numbers of people. These classifiers are moved through sign space to iconically represent the actions of their referents. For example, an ILY hand may 'lift off' or 'land on' a horizontal B hand to sign an aircraft taking off or landing; a 3 hand may be brought down on a B hand to sign parking a car; and a G hand may be brought toward a V hand to represent one person approaching two.

The frequency of classifier use depends greatly on genre, occurring at a rate of 17.7% in narratives but only 1.1% in casual speech and 0.9% in formal speech.[17]

Frames

Frames are a morphological device that may be unique to sign languages (Liddell 2004). They are incomplete sets of the features which make up signs, and they combine with existing signs, absorbing features from them to form a derived sign. It is the frame which specifies the number and nature of segments in the resulting sign, while the basic signs it combines with lose all but one or two of their original features.

One, the WEEKLY frame, consists of a simple downward movement. It combines with the signs for the days of the week, which then lose their inherent movement. For example, 'Monday' consists of an M/O hand made with a circling movement. 'MondayWEEKLY' (that is, 'on Mondays') is therefore signed as an M/O hand that drops downward, but without the circling movement. A similar ALL DAY frame (a sideward pan) combines with times of the day, such as 'morning' and 'afternoon', which likewise keep their handshape and location but lose their original movement. Numeral incorporation (see above) also uses frames. However, in ASL frames are most productively utilized for verbal aspect.

Verbal aspect

While there is no grammatical tense in ASL, there are numerous verbal aspects. These are produced by modulating the verb: Through reduplication, by placing the verb in an aspectual frame (see above), or with a combination of these means.

An example of an aspectual frame is the unrealized inceptive aspect ('just about to X'), illustrated here with the verb 'to tell'. 'To tell' is an indexical (directional) verb, where the index finger (a G hand) begins with a touch to the chin and then moves outward to point out the recipient of the telling. 'To be just about to tell' retains just the locus and the initial chin touch, which now becomes the final hold of the sign; all other features from the basic verb (in this case, the outward motion and pointing) are dropped and replaced by features from the frame (which are shared with the unrealized inceptive aspects of other verbs such as 'look at', 'wash the dishes', 'yell', 'flirt', etc.). These frame features are: Eye gaze toward the locus (which is no longer pointed at with the hand), an open jaw, and a hand (or hands, in the case of two-hand verbs) in front of the trunk which moves in an arc to the onset location of the basic verb (in this case, touching the chin), while the trunk rotates and the signer inhales, catching her breath during the final hold. The hand shape throughout the sign is whichever is required by the final hold, in this case a G hand.

The variety of aspects in ASL can be illustrated by the verb 'to be sick', which involves the middle finger of the Y/8 hand touching the forehead, and which can be modified by a large number of frames. Several of these involve reduplication, which may but need not be analyzed as part of the frame. (The appropriate non-manual features are not described here.)

- stative "to be sick" is made with simple iterated contact, typically with around four iterations. This is the basic, citation form of the verb.

- inchoative "to get sick, to take sick" is made with a single straight movement to contact and a hold of the finger on the forehead.

- predisposional "to be sickly, to be prone to get sick" is made with incomplete motion: three even circular cycles without contact. This aspect adds reduplication to verbs such as 'to look at' which do not already contain repetition.

- susceptative "to get sick easily" is made with a thrusting motion: The onset is held; then there is a brief, tense thrust that is checked before actual contact can be made.

- frequentative "to be often sick" is given a marcato articulation: A regular beat, with 4–6 iterations, and marked onsets and holds.

- susceptive and frequentative may be combined to mean "to get sick easily and often": Four brief thrusts on a marked, steady beat, without contact with the forehead.

- protractive "to be continuously sick" is made with a long, tense hold and no movement at all.

- incessant "to get sick incessantly" has a reduplicated tremolo articulation: A dozen tiny, tense, uneven iterations, as rapid as possible and without contact.

- durative "to be sick for a long time" is made with a reduplicated elliptical motion: Three slow, uneven cycles, with a heavy downward brush of the forehead and an arching return.

- iterative "to get sick over and over again" is made with three tense movements and slow returns to the onset position.

- intensive "to be very sick" is given a single tense articulation: A tense onset hold followed by a single very rapid motion to a long final hold.

- resultative "to become fully sick" (that is, a complete change of health) is made with an accelerando articulation: A single elongated tense movement which starts slowly and heavily, accelerating to a long final hold.

- approximative "to be sort of sick, to be a little sick" is made with a reduplicated lax articulation: A spacially extremely reduced, minimal movement, involving a dozen iterations without contact.

- semblitive "to appear to be sick" [no description]

- increasing "to get more and more sick" is made with the movements becoming more and more intense.

These modulations readily combine with each other to create yet finer distinctions. Not all verbs take all aspects, and the forms they do take will not necessarily be completely analogous to the verb illustrated here. Conversely, not all aspects are possible with this one verb.

Aspect is unusual in ASL in that transitive verbs derived for aspect lose their transitivity. That is, while you can sign 'dog chew bone' for the dog chewed on a bone, or 'she look-at me' for she looked at me, you cannot do the same in the durative to mean the dog gnawed on the bone or she stared at me. Instead, you must use other strategies, such as a topic construction (see below) to avoid having an object for the verb.

Verbal number

Reduplication is also used for expressing verbal number. Verbal number indicates that the action of the verb is repeated; in the case of ASL it is apparently limited to transitive verbs, where the motion of the verb is either extended or repeated to cover multiple object or recipient loci. (Simple plurality of action can also be conveyed with reduplication, but without indexing any object loci; in fact, such aspectual forms do not allow objects, as noted above.) There are specific dual forms (and for some signers trial forms), as well as plurals. With dual objects, the motion of the verb may be made twice with one hand, or simultaneously with both; while with plurals the object loci may be taken as a group by using a single sweep of the signing hand while the verbal motion is being performed, or individuated by iterating the move across the sweep. For example, 'to ask someone a question' is signed by flexing the index finger of an upright G hand in the direction of that person; the dual involves flexing it at both object loci (sequentially with one hand or simultaneously with both), the simple plural involves a single flexing which spans the object group while the hand arcs across it, and the individuated plural involves multiple rapid flexings while the hand arcs. If the singular verb uses reduplication, that is lost in the dual and plural forms.

Name signs

There are three types of personal name signs in ASL: fingerspelled, arbitrary, and descriptive. Fingerspelled names are simply spelled out letter-by-letter. Arbitrary name signs only refer to a person's name, while descriptive name signs refer to a person's personality or physical characteristics.[18] Once given, names are for life, apart from changing from one of the latter types to an arbitrary sign in childhood.[19] Name signs are usually assigned by another member of the Deaf community, and signal inclusion in that community. Name signs are not used to address people, as names are in English, but are used only for third-person reference, and usually only when the person is absent.[20]

The majority of people, probably well in excess of 90%, have arbitrary name signs. These are initialized signs: The hand shape is the initial of one of the English names of the person, usually the first.[21] The sign may occur in neutral space, with a tremble; with a double-tap (as a noun) at one of a limited number of specific locations, such as the side of the chin, the temple, or the elbow;[22] or moving across a location or between two locations, with a single tap at each.[23] Single-location signs are simpler in connotation, like English "Vee"; double-location signs are fancier, like English "Veronica". Sam Supalla (1992) collected 525 simple arbitrary name signs like these.

There are two constraints on arbitrary signs. First, it should not mean anything. That is, it should not duplicate an existing ASL word.[24] Second, there should not be more than one person with the name sign in the local community. If a person moves to a new community where someone already has their name sign, then the newcomer is obligated to modify theirs. This is usually accomplished by compounding the hand shape, so that the first tap of the sign takes the initial of the person's first English name, and the second tap takes the initial of their last name. There are potentially thousands of such compound-initial signs.

Descriptive name signs are not initialized, but rather use non-core ASL signs. They tend to be assigned and used by children, rather like "Blinky" in English. Parents do not give such names to their children, but most Deaf people do not have deaf parents and are assigned their name sign by classmates in their first school for the deaf. At most 10% of Deaf people retain such name signs into adulthood.. Arbitrary name signs became established very early in the history of ASL. Descriptive name signs refer to a person's appearance or personality.

The two systems, arbitrary and descriptive, are sometimes combined, usually for humorous purposes. Hearing people learning ASL are also often assigned combined name signs. This is not traditional for Deaf people. Sometimes people with very short English names, such as "Ann" or "Lee", or ones that flow easily, such as "Larry", may never acquire a name sign, but may instead be referred to with finger-spelling.

Parameters

There are 5 official parameters in American Sign Language that dictate meaning and grammar.[25] There is a 6th honorary parameter known as proximalization.[26]

Signs can share several of the same parameters. The difference in at least one parameter accounts for the difference in meaning or grammar.[27]

Handshape

Handshapes in ASL consist of the fingerspelling alphabet (A-Z) as well as other variations.[25] For BROWN and TAN, the location, movement, and palm orientation are the same, but the handshape differs. It consists of B for BROWN, and T for TAN.

The ASL handshape parameter contains over 55 handshapes, which is over double the amount contained in the Latin-script alphabet.[28] Some of the differences between these handshapes are small. These handshapes play into morphology and how meaning changes based on miniscule details.

Depending on the handshape, a different grammatical meaning can be portrayed.

Palm Orientation

The palm orientation in ASL refers to which direction the hand's center faces during a sign. There are documented differences possible for palm orientation:[25]

- Palm facing in/out

- Palm facing up/down

- Palm facing left/right

- Palm facing horizontal

- Palm facing toward other palm

These differences result in different semantic and structural meanings. The signs MAYBE and BALANCE have all of the same parameters except for palm orientation, resulting in different meanings.[28]

Movement

The movement parameter determines how and where the hand moves for a particular sign.[28] The hand can move up and down, forward and backward, in a circular motion, in a tapping rhythm, or many other ways. Like all other parameters, hand movement determines ASL grammar and diction meaning.

This parameter is also where derivational morphology in ASL is most noticeable.[4] Words change between nouns and verbs depending on the movement of the hand. Some examples of these differences are below:

SCISSORS (noun) → pointer and middle finger tap together in a 'cutting' fashion at least twice.

CUT (verb) → pointer and middle finger tap together once and more intensely.

AIRPLANE (noun) → sign for I LOVE YOU is moved forward and backward.

FLY (verb) → sign for I LOVE YOU is moved forward once.

EXAMPLE (noun) → dominant pointer points at non-dominant palm and is shaken in a particular direction at least twice.

SHOW (verb) → dominant pointer points at non-dominant palm and is moved in a particular direction once.

Location

The location parameter is the space in which your hands reside for a certain sign. This space is measured in adjacence to one's body, and resides within the signing space.

A sign may move from one location to another from the beginning to end.[25] Signs in ASL are fluid, and are not always stagnant in one location.

Some common locations for signing are:

- Chin

- Forehead

- Upper chest

- Shoulder

- Along the non-dominant arm

This list is non-exhaustive but a good indicator of where many signs reside.

Location changes word and sentence meaning, just like all other parameters.[29] APPLE and ONION have the same handshape, but different locations along the side of the face.

Non-Manual Markers (NMM)

Non-Manual Markers (NMM), or Non-Manual Signals (NMS) are communication methods not found in the hands. They typically consist of facial expressions and body language. NMMs can change the grammar of a sentence. Not every sign uses non-manual markers, but for many others, these markers determine what sign is being produced.[25]

Some examples of non-manual markers would be the shifting of shoulders, the lowering or raising of eyebrows, a head nod or shake, scrunching of the nose, pursing of the lips, or an open mouth.[30]

NMMs are important for indicating if a question is being asked. For WH- questions, the eyebrows are lowered, and for YES/NO questions, the eyebrows are raised.[31] It is hard to indicate if a question is being asked otherwise without facial indicators.

Another example would be between I UNDERSTAND and I DON'T UNDERSTAND. The sign for this is the same; the hand is held up near the forehead with the palm facing the self. The pointer finger is then extended. If the person is nodding and has their eyebrows raised, it means I UNDERSTAND. If they are shaking their head with eyebrows lowered, it means I DON'T UNDERSTAND.

Proximalization

This parameter is a linguistic feature only found in infants with ASL as a primary language. Babies learn and acquire more motor skills in the arms, shoulders, knuckles, and fingers thanks to the early acquisition of signed language.[27]

Due to the exclusivity of this characteristic, as well as being a physical attribute rather than a performed one, this parameter is not widely talked about. It is mostly shared between members of the Deaf community.[32]

Hand dominance

Understanding ASL grammar requires understanding the difference between a signer's dominant and non-dominant hand. If a person is right-handed, then their right hand is their dominant hand, and their left hand is their non-dominant hand. Almost all signs are completed with the more active, dominant hand, while the non-dominant hand serves as a base. For signs requiring two hands, the dominant hand performs more of the active component.[30]

Word order

ASL is a subject-verb-object (SVO) language.[33] However, OSV is also an accepted sentence form.[27]

Topic-comment order

The default SVO word order is sometimes altered by processes including topicalization and null elements.[34] This is marked either with non-manual signals like eyebrow or body position, or with prosodic marking such as pausing.[33] These non-manual grammatical markings (such as eyebrow movement or head-shaking) may optionally spread over the c-command domain of the node which it is attached to.[35] However, ASL is a pro-drop language, and when the manual sign that a non-manual grammatical marking is attached to is omitted, the non-manual marking obligatorily spreads over the c-command domain.[36]

The full sentence structure in ASL is [topic] [subject] verb [object] [subject-pronoun-tag]. Topics and tags are both indicated with non-manual features, and both give a great deal of flexibility to ASL word order.[37] Within a noun phrase, the word order is noun-number and noun-adjective.

ASL does not have a copula (linking 'to be' verb).[38] For example:

MY

HAIR

WET

my hair is wet

[name

my]TOPIC

P-E-T-E

my name is Pete

Noun-adjective order

In addition to its basic topic–comment structure, ASL typically places an adjective after a noun, though it may occur before the noun for stylistic purposes. Numerals also occur after the noun, a very rare pattern among oral languages.

DOG

BROWN

I

HAVE

I have a brown dog.

Adverbs, however, occur before the verbs. Most of the time adverbs are simply the same sign as an adjective, distinguished by the context of the sentence.

HOUSE

I

QUIET

ENTER

I enter the house quietly.

When the scope of the adverb is the entire clause, as in the case of time, it comes before the topic. This is the only thing which can appear before the topic in ASL: time–topic–comment.

9-HOUR

MORNING

STORE

I

GO

I'm going to the store at 9:00AM.

Modal verbs come after the main verb of the clause:

FOR

YOU,

STORE

I

GO

CAN

I can go to the store for you.

Time-sequenced clause ordering

ASL makes heavy use of time-sequenced ordering, meaning that events are signed in the order in which they occur. For example, for I was late to class last night because my boss handed me a huge stack of work after lunch yesterday, one would sign 'YESTERDAY LUNCH FINISH, BOSS GIVE-me WORK BIG-STACK, NIGHT CLASS LATE-me'. In stories, however, ordering is malleable, since one can choose to sequence the events either in the order in which they occurred or in the order in which one found out about them.

Tense and aspect

It has been claimed that tense in ASL is marked adverbially, and that ASL lacks a separate category of tense markers.[39] However, Aarons et al. (1992, 1995) argue that "Tense" (T) is indeed a distinct category of syntactic head, and that the T node can be occupied either by a modal (e.g. SHOULD) or a lexical tense marker (e.g. FUTURE-TENSE).[39] They support this claim by noting that only one such item can occupy the T slot:[40]

REUBEN

CAN

RENT

VIDEO-TAPE

'Reuben can rent a video tape.'

REUBEN

WILL

RENT

VIDEO-TAPE

'Reuben will rent a video tape.'

*

REUBEN

CAN

WILL

RENT

VIDEO-TAPE

* 'Reuben can will rent a video tape.'

Aspect may be marked either by verbal inflection or by separate lexical items.[41]

These are ordered: Tense – Negation – Aspect – Verb:[42]

neg (non-manual negation marker) GINGER SHOULD NOT EAT BEEF 'Ginger should not eat beef.' neg DAVE NOT FINISH SEE MOVIE 'Dave did not see (to completion) the movie.'

Aspect, topics, and transitivity

As noted above, in ASL aspectually marked verbs cannot take objects. To deal with this, the object must be known from context so that it does not need to be further specified. This is accomplished in two ways:

- The object may be made prominent in a prior clause, or

- It may be used as the topic of the utterance at hand.

Of these two strategies, the first is the more common. For my friend was typing her term paper all night to be used with a durative aspect, this would result in

my friend type T-E-R-M paper. typeDURATIVE all-night

The less colloquial topic construction may come out as,

[my friend]TOPIC, [T-E-R-M paper]TOPIC, typeDURATIVE all-night

CP Syntax

Topics and main clauses

A topic sets off background information that will be discussed in the following main clause. Topic constructions are not often used in standard English, but they are common in some dialects, as in,

That dog, I never could hunt him.

Topicalization is used productively in ASL and often results in surface forms that do not follow the basic SVO word order.[43] In order to non-manually mark topics, the eyebrows are raised and the head is tilted back during the production of a topic. The head is often lowered toward the end of the sign, and sometimes the sign is followed rapidly nodding the head. A slight pause follows the topic, setting it off from the rest of the sentence:[44]

[MEAT]tm,

I

LIKE

LAMB

As for meat, I prefer lamb.

Another way topics may be signed is by shifting the body. The signer may use the space on one side of his/her body to sign the topic, and then shifts to the other side for the rest of the sentence.[44]

ASL utterances do not require topics, but their use is extremely common. They are used for purposes of information flow, to set up referent loci (see above), and to supply objects for verbs which are grammatically prevented from taking objects themselves (see below).

Without a topic, the dog chased my cat is signed:

DOG

CHASE

MY

CAT

The dog chased my cat

However, people tend to want to set up the object of their concern first and then discuss what happened to it. English does this with passive clauses: my cat was chased by the dog. In ASL, topics are used with similar effect:

[MY

CAT]tm

DOG

CHASE

lit. 'my cat, the dog chased it.'

If the word order of the main clause is changed, the meaning of the utterance also changes:

[MY

CAT]tm

CHASE

DOG

'my cat chased the dog,'

lit. 'my cat, it chased the dog.'

There are three types of non-manual topic markers, all of which involve raised eyebrows.[45] The three types of non-manual topic markers are used with different types of topics and in different contexts, and the topic markings cannot spread over other elements in the utterance. Topics can be moved from and remain null in the main clause of an utterance, or topics can be base-generated and either be co-referential to either the subject or object in the main clause or be related to the subject of object by a semantic property.[46]

The first type of non-manual marking, topic marking 1 (tm1), is only used with a moved topic.[47] Tm1 is characterized by raised eyebrows, widened eyes, and head tilted backwards. At the end of the sign the head moves down and there is a pause, often with an eye blink, before the sentence is continued.[48] The following is an example of a context in which the tm1 marking is used:

Topic marking 2 (tm2) and topic marking 3 (tm3) are both used with base-generated topics. Tm2 is characterized by raised eyebrows, widened eyes, and the head tilted backwards and to the side. Toward the end of the sign the head moves forward and to the opposite side, and there is a pause and often an eye blink before continuing.[50] For tm3 the eyebrows are raised and the eyes are opened wide, the head starts tilted down and jerks up and down, the lips are opened and raised, and the head is nodded rapidly a few times before pausing and continuing the sentence. Although both tm2 and tm3 accompany base-generated topics, they are used in different contexts. Tm2 is used to introduce new information and change the topic of a conversation to something that the signer is going to subsequently characterize, while tm3 is used to introduce new information that the signer believes is already known by his/her interlocutor.[51] Tm2 may be used with any base-generated topic, whereas only topics that are co-referential with an argument in the sentence may be marked with tm3.[52]

An example of a tm2 marking used with a topic related to the object of the main clause is:

An example of a tm2 marking used with a co-referential topic is:

IX-3rd represents a 3rd person index.

Another example of a tm2 marking with a co-referential topic is:

An example of a tm3 topic marking is:

ASL sentences may have up to two marked topics.[45] Possible combinations of topic types are two tm2 topics, two tm3 topics, tm2 preceding tm1, tm3 preceding tm1, and tm2 preceding tm3. Sentences with these topic combinations in the opposite orders or with two tm1 topics are considered ungrammatical by native signers.[55]

Relative clauses

Relative clauses are signaled by tilting back the head and raising the eyebrows and upper lip. This is done during the performance of the entire clause. There is no change in word order. For example:

[recently

dog

chase

cat]RELATIVE

come

home

The dog which recently chased the cat came home

where the brackets here indicate the duration of the non-manual features. If the sign 'recently' were made without these features, it would lie outside the relative clause, and the meaning would change to "the dog which chased the cat recently came home".

Negated clauses

Negated clauses may be signaled by shaking the head during the entire clause. A topic, however, cannot be so negated; the headshake can only be produced during the production of the main clause. (A second type of negation starts with the verb and continues to the end of the clause.)

In addition, in many communities, negation is put at the end of the clause, unless there is a wh- question word. For example, the sentence, "I thought the movie was not good," could be signed as, "BEFORE MOVIE ME SEE, THINK WHAT? IT GOOD NOT."

There are two manual signs that negate a sentence, NOT and NONE, which are accompanied by a shake of the head. NONE is typically used when talking about possession:

DOG

I

HAVE

NONE

I don't have any dogs.

NOT negates a verb:

TENNIS

I

LIKE

PLAY

NOT

I don't like to play tennis.

Interrogative clauses

There are three types of questions with different constructions in ASL: wh- questions, yes/no questions, and rhetorical questions.[56]

Non-manual grammatical markings

Non-manual grammatical markings are grammatical and semantic features that do not include the use of hands. They can include mouth shape, eye gazes, facial expressions, body shifting, head tilting, and eyebrow raising. Non -manual grammatical markings can also aid in identifying sentence type, which is especially relevant to our discussion of different types of interrogatives.[57]

Wh-questions

Wh-questions can be formed in a variety of ways in ASL. The wh-word can appear solely at the end of the sentence, solely at the beginning of the sentence, at both the beginning and end of the sentence (see section 4.4.2.1 on 'double-occurring wh-words', or in situ (i.e. where the wh-word is in the sentence structure before movement occurs)).[58] Manual wh-signs are also accompanied by a non-manual grammatical marking (see section 4.4.1), which can include a variety of features.[59] This non-manual grammatical marking can spread optionally over the entire wh-phrase or just a small part.

Some languages have very few wh-words, where context and discourse are sufficient to elicit the information that one needs. ASL has many different wh-words, with certain wh-words having multiple variations. A list of the wh-words of ASL can be found below. WHAT, WHAT-DO, WHAT-FOR, WHAT-PU, WHAT- FS, WHEN, WHERE, WHICH, WHO (several variations), WHY, HOW, HOW-MANY[60]

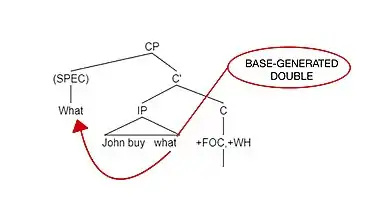

Double-occurring wh-words

As mentioned above, ASL possesses wh-questions with word initial placement, word final placement, in situ structure, but the most unique style of wh-word occurrence in ASL is where the wh-word occurs twice, copied in final position.[61] This doubling can be seen in the table below.

| WHAT | JOHN | BUY | WHAT |

| 'what did John buy' | |||

This doubling provides a useful template to analyze two separate analyses about whether wh-words move rightward or leftward in ASL. While some researchers argue for rightward movement in wh- questions such as Aarons and Neidle,[62] others, including Petronio and Lillo-Martin, have argued that ASL has leftward movement and wh- words that appear to the right of the clause move by other processes.[63] Both analyses agree upon the fact that there is wh-movement present in these interrogative phrases, but it is a matter of what direction the wh-movement is moving in that causes controversy. No matter what direction the wh-movement is analyzed to go in, it is crucial to the analysis that the movement of the wh-element is to the position of SPEC CP[64]

Lillo-Martin & Fischer's, and Petronio's leftward wh-movement analysis

Summary of the leftward wh-movement analysis in American Sign Language:

The leftward movement analysis is congruent with cross linguistic data that wh-movement is always leftward. It can be seen as the less controversial of the two proposals. The main arguments presented by the Leftward Wh-movement analysis are: That the spec-CP is on the left, that the wh-movement is leftward, and that the final wh-word in a sentence is a base-generated double. This is illustrated in the syntax tree located to the right of this paragraph.[65] Arguments for leftward movement are based on the facts that if wh-movement in ASL were rightward, ASL would be an exception to cross-linguistic generalizations that wh-movement is leftward.[63]

It has also been hypothesized that wh-elements cannot be topicalized, as topicalized elements must be presupposed and interrogatives are not.[66] This would be detrimental to the rightward analysis, as they are analyzing the doubled wh-word as a 'base generated topic'.

Aarons et al.'s rightward wh-movement analysis

Summary of the rightward wh-movement analysis in American Sign Language

The rightward movement analysis is a newer, more abstract argument of how wh-movement occurs in ASL. The main arguments for rightward movement begin by analyzing spec-CP as being on the right, the wh-movement as being rightward, and as the initial wh-word as a base-generated topic.[67] This can be seen in the syntax tree on the right.

One of the rightward movement analysis' main arguments is in regards to the non-manual grammatical markings, and their optional spreading over the sentence. In ASL the use of non-manual grammatical markings is optional depending on the type of wh-question being asked. In the rightward analysis both partial and full spreading of non-manual grammatical markers can be accounted for due to the association with the +WH feature over its c-command domain.[68] In the leftward analysis, the partial or full spreading of non manual grammatical markings cannot be accounted for in this same way. The leftward movement analysis requires wh-marking to extend over the entirety of the question, regardless (which is not what is attested in ASL).

Yes/no questions

In spoken language Yes/no questions will oftentimes differ in their word order from the statement form. For example, in English:

English Statement:

HE WILL BUY THE SHIRT.

English Yes/no Q:

WILL HE BUY THE SHIRT?[69]

In ASL, yes/no questions are marked by the non-manual grammatical markings (as discussed in section 4.4.1). This eyebrow raise, slight tilt of the head and lean forward are what indicate that a yes/no question is being asked, without any change in word order from the statement form. There is speculation amongst linguists that these non-manual grammatical markings that indicate a yes/no questions are similar to the question intonation of spoken languages.[70]

Yes/no questions differ from wh-questions as they do not differ in word order from the original statement form of the sentence, whereas wh-questions do. As well, in yes/no questions, the non-manual marking must be used over the whole utterance in order for it to be judged as a statement opposed to a question.[71] The yes/no question is the same word order as the statement form of the sentence, with the addition of non-manual grammatical markings. This can be seen in the examples below.

ASL Statement:

JUAN WILL BUY SHOES TODAY "Juan will buy shoes today"

ASL Yes/no Question:

_____________________brow raise

JUAN WILL BUY SHOES TODAY

"Will Juan buy shoes today?"[72]

Rhetorical questions

Non-manual grammatical markings are also used for rhetorical questions, which are questions that do not intend to elicit an answer. To distinguish the non-manual marking for rhetorical questions from that of yes/no questions, the body is in a neutral position opposed to tilted forward, and the head is tilted in a different way than in yes/no questions.[73] Rhetorical questions are much more common in ASL than in English. For example, in ASL:

[I

LIKE]NEGATIVE

[WHAT?]RHETORICAL,

GARLIC.

"I don't like garlic"

This strategy is commonly used instead of signing the word 'because' for clarity or emphasis. For instance:

PASTA

I

EAT

ENJOY

TRUE

[WHY?]RHETORICAL,

ITALIAN

I.

"I love to eat pasta because I am Italian"

DP syntax

Subject pronoun tags

Information may also be added after the main clause as a kind of 'afterthought'. In ASL this is commonly seen with subject pronouns. These are accompanied by a nod of the head, and make a statement more emphatic:

boy

fall

"The boy fell down."

versus

boy

fall

[he]TAG

"The boy fell down, he did."

The subject need not be mentioned, as in

fall

"He fell down."

versus

fall

[he]TAG

"He fell down, he did."

Deixis

In ASL signers set up regions of space (loci) for specific referents (see above); these can then be referred to indexically by pointing at those locations with pronouns and indexical verbs.

Pronouns

Personal pronouns in ASL are indexic. That is, they point to their referent, or to a locus representing their referent. When the referent is physically present, pronouns involve simply pointing at the referent, with different handshapes for different pronominal uses: A 'G' handshape is a personal pronoun, an extended 'B' handshape with an outward palm orientation is a possessive pronoun, and an extended-thumb 'A' handshape is a reflexive pronoun; these may be combined with numeral signs to sign 'you two', 'us three', 'all of them', etc.

If the referent is not physically present, the speaker identifies the referent and then points to a location (the locus) in the sign space near their body. This locus can then be pointed at to refer to the referent. Theoretically, any number of loci may be set up, as long as the signer and recipient remember them all, but in practice, no more than eight loci are used.

Meier 1990 demonstrates that only two grammatical persons are distinguished in ASL: First person and non-first person, as in Damin. Both persons come in several numbers as well as with signs such as 'my' and 'by myself'.

Meier provides several arguments for believing that ASL does not formally distinguish second from third person. For example, when pointing to a person that is physically present, a pronoun is equivalent to either 'you' or '(s)he' depending on the discourse. There is nothing in the sign itself, nor in the direction of eye gaze or body posture, that can be relied on to make this distinction. That is, the same formal sign can refer to any of several second or third persons, which the indexic nature of the pronoun makes clear. In English, indexic uses also occur, as in 'I need you to go to the store and you to stay here', but not so ubiquitously. In contrast, several first-person ASL pronouns, such as the plural possessive ('our'), look different from their non-first-person equivalents, and a couple of pronouns do not occur in the first person at all, so first and non-first persons are formally distinct.

Personal pronouns have separate forms for singular ('I' and 'you/(s)he') and plural ('we' and 'you/they'). These have possessive counterparts: 'my', 'our', 'your/his/her', 'your/their'. In addition, there are pronoun forms which incorporate numerals from two to five ('the three of us', 'the four of you/them', etc.), though the dual pronouns are slightly idiosyncratic in form (i.e., they have a K rather than 2 handshape, and the wrist nods rather than circles). These numeral-incorporated pronouns have no possessive equivalents.

Also among the personal pronouns are the 'self' forms ('by myself', 'by your/themselves', etc.). These only occur in the singular and plural (there is no numeral incorporation), and are only found as subjects. They have derived emphatic and 'characterizing' forms, with modifications used for derivation rather like those for verbal aspect. The 'characterizing' pronoun is used when describing someone who has just been mentioned. It only occurs as a non-first-person singular form.

Finally, there are formal pronouns used for honored guests. These occur as singular and plural in the non-first person, but only as singular in the first person.

ASL is a pro-drop language, which means that pronouns are not used when the referent is obvious from context and is not being emphasized.

Indexical verbs

Within ASL there is a class of indexical (often called 'directional') verbs. These include the signs for 'see', 'pay', 'give', 'show', 'invite', 'help', 'send', 'bite', etc. These verbs include an element of motion that indexes one or more referents, either physically present or set up through the referent locus system. If there are two loci, the first indicates the subject and the second the object, direct or indirect depending on the verb, reflecting the basic word order of ASL. For example, 'give' is a bi-indexical verb based on a flattened M/O handshape. For 'I give you', the hand moves from myself toward you; for 'you give me', it moves from you to me. 'See' is indicated with a V handshape. Two loci for a dog and a cat can be set up, with the sign moving between them to indicate 'the dog sees the cat' (if it starts at the locus for dog and moves toward the locus for cat) or 'the cat sees the dog' (with the motion in the opposite direction), or the V hand can circulate between both loci and myself to mean 'we (the dog, the cat, and myself) see each other'. The verb 'to be in pain' (index fingers pointed at each other and alternately approaching and separating) is signed at the location of the pain (head for headache, cheek for toothache, abdomen for stomachache, etc.). This is normally done in relation to the signer's own body, regardless of the person feeling the pain, but may take also use the locus system, especially for body parts which are not normally part of the sign space, such as the leg. There are also spatial verbs such as put-up and put-below, which allow signers to specify where things are or how they moved them around.

Conjunctions

There is no separate sign in ASL for the conjunction and. Instead, multiple sentences or phrases are combined with a short pause between. Often, lists are specified with a listing and ordering technique, a simple version of which is to show the length of the list first with the nondominant hand, then to describe each element after pointing to the nondominant finger that represents it.

- English: I have three cats and they are named Billy, Bob, and Buddy.

- ASL: CAT I HAVE THREE-LIST. NAME, FIRST-OF-THREE-LIST B-I-L-L-Y, SECOND-OF-THREE-LIST B-O-B, THIRD-OF-THREE-LIST B-U-D-D-Y.

There is a manual sign for the conjunction or, but the concept is usually signed nonmanually with a slight shoulder twist.

- English: I'll leave at 5 or 6 o'clock.

- ASL: I LEAVE TIME 5 [shoulder shift] TIME 6.

The manual sign for the conjunction but is similar to the sign for different. It is more likely to be used in Pidgin Signed English than in ASL. Instead, shoulder shifts can be used, similar to "or" with appropriate facial expression.

- English: I like to swim, but I don't like to run.

- ASL/PSE: SWIM I LIKE, BUT RUN I LIKE-NOT

- ASL: SWIM I LIKE, [shoulder shift] RUN I LIKE-NOT

Notes

- Armstrong, David F.; Karchmer, Michael A. (2009). "William C. Stokoe and the Study of Signed Languages". Sign Language Studies. 9 (4): 389–397. ISSN 0302-1475. JSTOR 26190588.

- Stokoe, William C. (October 1980). "Sign Language Structure". Annual Review of Anthropology. 9 (1): 365–390. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.09.100180.002053. ISSN 0084-6570.

- "Morphology". Asl linguistics. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- Lillo-Martin, Diane; Sandler, Wendy, eds. (2006), "Derivational morphology", Sign Language and Linguistic Universals, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–75, ISBN 978-0-521-48395-7, retrieved October 16, 2023

- Bahan (1996:20)

- Bahan (1996:21)

- Bahan (1996:21–22)

- Bahan (1996:22–23)

- Bahan (1996:23)

- Bahan (1996:24)

- Bahan (1996:25)

- Bahan (1996:50)

- Bahan (1996:50–51)

- Aronoff, M., Meir, I., & Sandler, W. (2005). The paradox of sign language morphology. Language, 81(2), 301.

- Supalla, T. R. (1982). Structure and acquisition of verbs of motion and location in American Sign Language (Doctoral dissertation, ProQuest Information & Learning).

- Supalla, T. (1986). The classifier system in American sign language. Noun classes and categorization, 181–214.

- Morford, Jill; MacFarlane, James (2003). "Frequency Characteristics of American Sign Language". Sign Language Studies. 3 (2): 213. doi:10.1353/sls.2003.0003. S2CID 6031673.

- Supalla, Samuel J. (1990). "The Arbitrary Name Sign System in American Sign Language". Sign Language Studies. 1067 (1): 99–126. doi:10.1353/sls.1990.0006. ISSN 1533-6263. S2CID 144191789.

- "Types and trends of name signs in the Swedish Sign Language community" (PDF).

- Samuel J. Supalla (1992) The Book of Name Signs: Naming in American Sign Language.

- The J hand shape is articulated with a brush of the pinkie finger against the sign location. It cannot occur in neutral space. There is no provision for Z: that is, there are no Z-initial arbitrary name signs.

- Contrastive locations are limited to the temple, forehead, side of chin, chin, shoulder, chest, outside of elbow, inside of elbow, palm of a vertical flat hand, back of a horizontal back hand. Some name signs are distinguished by orientation. For example, an I hand shape may make contact with either the tip of the pinkie finger or the side of the thumb; the M hand shape with either the tips of the three fingers or the side of the index finger, etc.

- The two locations are usually close by, such as the hand moving across the chin or down the chest, but may occasionally be further apart, as from the shoulder to the back of the hand.

- There are occasional exceptions to this constraint. For example, I. King Jordan's name sign is homophonous with "king" (K hand moving from the shoulder to the hip).

- Mt. San Antonio College. https://www.mtsac.edu/llc/passportrewards/languagepartners/5ParametersofASL.pdf

- "Proximalization in sign language linguistics". www.handspeak.com. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- "Log In to Canvas". asl.instructure.com. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- "Parameters: handshape, location, movement, palm orientation". www.handspeak.com. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- Mauk CE, Tyrone ME. Location in ASL: Insights from phonetic variation. Sign Lang Linguist. 2012 Apr 1;15(1):128-146. doi: 10.1075/sll.15.1.06mau. PMID: 26478715; PMCID: PMC4606891.

- Brentari, Diane; Crossley, Laurinda (January 1, 2002). "Prosody on the hands and face: Evidence from American Sign Language". Sign Language & Linguistics. 5 (2): 105–130. doi:10.1075/sll.5.2.03bre. ISSN 1387-9316.

- Watson, Katharine L (January 1, 2010). "WH-questions in American Sign Language: Contributions of non-manual marking to structure and meaning". Theses and Dissertations Available from ProQuest: 1–130.

- Mirus, G., Rathmann, Christian & Meier, Richard. (2001, January). Proximalization and distalization of sign movement in adult learners. Signed languages: Discoveries from international research, 103, 119. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313238398_Proximalization_and_distalization_of_sign_movement_in_adult_learners

- Bahan (1996:30)

- Pichler, Deborah Chen (2001). Word order variation and acquisition in American Sign Language. pp. 14–15.

- Bahan (1996:31)

- Neidle, Carol (2002). "Language across modalities". Linguistic Variation Yearbook. 2 (1): 71–98. doi:10.1075/livy.2.05nei.

- Aarons, DebraAspects of the syntax of American Sign Language (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 55.

- Pichler, Deborah Chen (2001). Word order variation and acquisition in American Sign Language. p. 23.

- Bahan (1996:33)

- Bahan (1996:33–34)

- Bahan (1996:27)

- Bahan (1996:34–37)

- Pichler, Deborah Chen (2001). Word order variation and acquisition in American Sign Language. p. 15.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 70.

- Bahan (1996:41–42)

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. pp. 151–153.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 155.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. pp. 156–157.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 157.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 160.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. pp. 163–165.

- Pichler, Deborah Chen (2001). Word order variation and acquisition in American Sign Language. pp. 28–29.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 162.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the Syntax of American Sign Language. p. 165.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. pp. 177–181.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. pp. 67–69.

- "Non-manual signals in sign language". www.handspeak.com. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- Petronio, Karen; Diane Lillo-Martin (1997). "Wh-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language" (PDF). Linguistic Society of America. 73 (1): 18–57. doi:10.2307/416592. JSTOR 416592.

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 69.

- Joseph Christopher Hill; Diane C. Lillo-Martin; Sandra K. Wood (2019). Sign languages: structures and contexts. London. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-429-02087-2. OCLC 1078875378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Josep Quer; Roland Pfau; Annika Herrmann (2021). The Routledge handbook of theoretical and experimental sign language research. Abingdon, Oxon. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-317-62427-1. OCLC 1182020388.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Neidle, Carol (2002). "Language across modalities: ASL focus and question constructions". Linguistic Variation Yearbook. 2 (1): 71–98. doi:10.1075/livy.2.05nei.

- Petronio, Karen; Lillo-Martin, Diane (1997). "WH-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language". Language. 73 (1): 18–57. doi:10.2307/416592. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 416592.

- Petronio, Karen; Lillo-Martin, Diane (March 1997). "WH-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language". Language. 73 (1): 21. doi:10.2307/416592. JSTOR 416592.

- Josep Quer; Roland Pfau; Annika Herrmann (2021). The Routledge handbook of theoretical and experimental sign language research. Abingdon, Oxon. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-317-62427-1. OCLC 1182020388.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Petronio, Karen; Lillo-Martin, Diane (March 1997). "WH-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language". Language. 73 (1): 22. doi:10.2307/416592. JSTOR 416592.

- Petronio, Karen; Lillo-Martin, Diane (March 1997). "WH-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language". Language. 73 (1): 18. doi:10.2307/416592. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 416592.

- Neidle, Carol; MacLaughlin, Dawn; Lee, Robert G.; Bahan, Benjamin; Kegl, Judy (1998). "The Rightward Analysis of wh-Movement in ASL: A Reply to Petronio and Lillo-Martin". Language. 74 (4): 823–825. doi:10.2307/417004. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 417004.

- Baker, Anne; et al. (2016). The Linguistics of Sign Languages: An Introduction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 130. ISBN 9789027212306.

- Baker, Anne (July 8, 2016). The linguistics of sign languages : an introduction. Amsterdam. p. 131. ISBN 978-90-272-6734-4. OCLC 936433607.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 92.

- Hill, Joseph C.; Lillo-Martin, Diane C.; Wood, Sandra K. (2018), "Syntax", Sign Languages, New York: Routledge, pp. 55–81, doi:10.4324/9780429020872-4, ISBN 978-0-429-02087-2, S2CID 239556102, retrieved April 18, 2022

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language. p. 68.

References

- Aarons, Debra (1994). Aspects of the syntax of American Sign Language (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Boston University, Boston, MA.

- Bahan, Benjamin (1996). Non-Manual Realization of Agreement in American Sign Language (PDF). Boston University. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- Klima, Edward & Bellugi, Ursula (1979). The Signs of Language. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- Liddell, Scott K. (2003). Grammar, Gesture, and Meaning in American Sign Language. Cambridge University Press.

- Neidle, Carol (2002). Language across Modalities: ASL focus and question constructions. Linguistic Variation Yearbook, 2(1), 71–98.

- Petronio, Karen, & Lillo-Martin, Diane (1997). WH-Movement and the Position of Spec-CP: Evidence from American Sign Language. Language, 73(1), 18–57.

- Pichler, Debora Chen (2001). Word order variation and acquisition in American Sign Language (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Connecticut.

- Stokoe, William C. (1976). Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Linstok Press. ISBN 0-932130-01-1.

- Stokoe, William C. (1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No. 8). Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- Mirus, G., Rathmann, Christian & Meier, Richard. (2001, January). Proximalization and distalization of sign movement in adult learners. Signed languages: Discoveries from international research, 103, 119.

Further reading

- Signing Naturally by Ken Mikos

- The Syntax of American Sign Language: Functional Categories and Hierarchical Structure by Carol Jan Neidle

- Grammar, Gesture, and Meaning in American Sign Language by Scott K. Liddell

- Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction, 4th Ed. by Clayton Valli