Azerbaijanis

Azerbaijanis (/ˌæzərbaɪˈdʒæni, -ɑːni/; Azerbaijani: Azərbaycanlılar, آذربایجانلیلار), Azeris (Azerbaijani: Azərilər, آذریلر), or Azerbaijani Turks (Azerbaijani: Azərbaycan Türkləri, آذربایجان تۆرکلری)[45][46][47] are a Turkic ethnic group living mainly in the Azerbaijan region of northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are predominantly Shia Muslims.[42] They comprise the largest ethnic group in the Republic of Azerbaijan and the second-largest ethnic group in neighboring Iran and Georgia.[48] They speak the Azerbaijani language, belonging to the Oghuz branch of the Turkic languages.

Azərbaycanlılar آذربایجانلیلار | |

|---|---|

Azerbaijani girls in traditional dresses | |

| Total population | |

| 30–35 million[1] (2002) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 12–23 million[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] | |

| 8,172,800[11] | |

| 603,070[12] | |

| 530,000–2 million[13][1] | |

| 233,178[14] | |

| 114,586[15] | |

| 45,176[16] | |

| 44,400[17] | |

| 33,365[18] | |

| 24,377[19][20][21] | |

| 20,000–30,000[22] | |

| 18,000[23] | |

| 17,823[24] | |

| 70,000[25] | |

| 9,915[26] | |

| 8,000[27][28][29] | |

| 7,000[30] | |

| 6,220[31] | |

| 5,567[32] | |

| 2,935[33] | |

| 1,567–2,032[34][35] | |

| 1,036[36] | |

| 1,000[37] | |

| 940[38] | |

| 806[39] | |

| 648[40] | |

| 552[41] | |

| Languages | |

| Azerbaijani Persian, Turkish | |

| Religion | |

| Mainly Islam (predominantly Shia Islam,[42] minority Sunni Islam) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turkish people[43] and Turkmen people[44] | |

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Persecution |

Following the Russo-Persian Wars of 1813 and 1828, the territories of Qajar Iran in the Caucasus were ceded to the Russian Empire and the treaties of Gulistan in 1813 and Turkmenchay in 1828 finalized the borders between Russia and Iran.[49][50] After more than 80 years of being under the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was established in 1918 which defined the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

Etymology

Azerbaijan is believed to be named after Atropates, a Persian[51][52][53] satrap (governor) who ruled in Atropatene (modern Iranian Azerbaijan) circa 321 BC.[54][55]: 2 The name Atropates is the Hellenistic form of Old Persian Aturpat which means 'guardian of fire'[56] itself a compound of ātūr (![]() ) 'fire' (later ādur (آذر) in (early) New Persian, and is pronounced āzar today)[57] + -pat (

) 'fire' (later ādur (آذر) in (early) New Persian, and is pronounced āzar today)[57] + -pat (![]() ) suffix for -guardian, -lord, -master[57] (-pat in early Middle Persian, -bod (بُد) in New Persian).

) suffix for -guardian, -lord, -master[57] (-pat in early Middle Persian, -bod (بُد) in New Persian).

Present-day name Azerbaijan is the Arabicized form of Āzarpāyegān (Persian: آذرپایگان) meaning 'the guardians of fire' later becoming Azerbaijan (Persian: آذربایجان) due to the phonemic shift from /p/ to /b/ and /g/ to /dʒ/ which is a result of the medieval Arabic influences that followed the Arab invasion of Iran, and is due to the lack of the phoneme /p/ and /g/ in the Arabic language.[58] The word Azarpāyegān itself is ultimately from Old Persian Āturpātakān (Persian: آتورپاتکان)[59][60] meaning 'the land associated with (satrap) Aturpat' or 'the land of fire guardians' (-an, here garbled into -kān , is a suffix for association or forming adverbs and plurals;[57] e.g.: Gilan 'land associated with Gil people').[61]

Ethnonym

The modern ethnonym "Azerbaijani" or "Azeri" refers to the Turkic peoples of Iran's northwestern historic region of Azerbaijan (also known as Iranian Azerbaijan) and the Republic of Azerbaijan.[62] They historically called themselves or were referred to by others as Muslims, Turks. They were also referred to as Ajam (meaning from Iran), using the term incorrectly to denote their Shia belief rather than ethnic identity.[63] When the Southern Caucasus became part of the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century, the Russian authorities, who traditionally referred to all Turkic people as Tatars, defined Tatars living in the Transcaucasus region as Caucasian Tatars or more rarely[64] Aderbeijanskie (Адербейджанские) Tatars or even[65] Persian Tatars in order to distinguish them from other Turkic groups and the Persian speakers of Iran.[65][66] The Russian Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, written in the 1890s, also referred to Tatars in Azerbaijan as Aderbeijans (адербейджаны),[67] but noted that the term had not been widely adopted.[68] This ethnonym was also used by Joseph Deniker in 1900.[69] In Azerbaijani language publications, the expression "Azerbaijani nation" referring to those who were known as Tatars of the Caucasus first appeared in the newspaper Kashkul in 1880.[70]

During the early Soviet period, the term "Transcaucasian Tatars" was supplanted by "Azerbaijani Turks" and ultimately "Azerbaijanis."[71][72][73] For some time afterwards, the term "Azerbaijanis" was then applied to all Turkic-speaking Muslims in Transcaucasia, from the Meskhetian Turks in southwestern Georgia, to the Terekemes of southern Dagestan, as well as assimilated Tats and Talysh.[72] The temporary designation of Meskhetian Turks as "Azerbaijanis" was most likely related to the existing administrative framework of the Transcaucasian SFSR, as the Azerbaijan SSR was one of its founding members.[74] After the establishment of the Azerbaijan SSR,[75] on the order of Soviet leader Stalin, the "name of the formal language" of the Azerbaijan SSR was also "changed from Turkic to Azerbaijani".[75]

Exonym

The Chechen and Ingush names for Azerbaijanis[lower-alpha 1] are Ghezloy/Ghoazloy (ГӀезлой/ГӀоазлой) and Ghazaroy/Ghazharey (ГӀажарой/ГӀажарей). The former goes back to the name of Qizilbash while the latter goes back to the name of Qajars, having presumably emerged in Chechen and Ingush languages during the reign of Qajars in Iran in the 18th-19th centuries.[77]

History

Ancient residents of the area spoke Old Azeri from the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages.[78] In the 11th century AD with Seljuq conquests, Oghuz Turkic tribes started moving across the Iranian Plateau into the Caucasus and Anatolia. The influx of the Oghuz and other Turkmen tribes was further accentuated by the Mongol invasion.[79] These Turkmen tribes spread as smaller groups, a number of which settled down in the Caucasus and Iran, resulting in the Turkification of the local population. Over time they converted to Shia Islam and gradually absorbed Azerbaijan and Shirvan.[80]

Ancient period

Caucasian-speaking Albanian tribes are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of the region in the north of Aras river, where the Republic of Azerbaijan is located.[81] The region also saw Scythian settlement in the ninth century BC, following which the Medes came to dominate the area to the south of the Aras River.[82]

Alexander the Great defeated the Achaemenids in 330 BC, but allowed the Median satrap Atropates to remain in power. Following the decline of the Seleucids in Persia in 247 BC, an Armenian Kingdom exercised control over parts of Caucasian Albania.[83] Caucasian Albanians established a kingdom in the first century BC and largely remained independent until the Persian Sassanids made their kingdom a vassal state in 252 AD.[2]: 38 Caucasian Albania's ruler, King Urnayr, went to Armenia and then officially adopted Christianity as the state religion in the fourth century AD, and Albania remained a Christian state until the 8th century.[84][85]

Medieval period

Sassanid control ended with their defeat by the Rashidun Caliphate in 642 AD through the Muslim conquest of Persia.[86] The Arabs made Caucasian Albania a vassal state after the Christian resistance, led by Prince Javanshir, surrendered in 667.[2]: 71 Between the ninth and tenth centuries, Arab authors began to refer to the region between the Kura and Aras rivers as Arran.[2]: 20 During this time, Arabs from Basra and Kufa came to Azerbaijan and seized lands that indigenous peoples had abandoned; the Arabs became a land-owning elite.[87]: 48 Conversion to Islam was slow as local resistance persisted for centuries and resentment grew as small groups of Arabs began migrating to cities such as Tabriz and Maraghah. This influx sparked a major rebellion in Iranian Azerbaijan from 816 to 837, led an Iranian Zoroastrian commoner named Babak Khorramdin.[88] However, despite pockets of continued resistance, the majority of the inhabitants of Azerbaijan converted to Islam. Later, in the 10th and 11th centuries, parts of Azerbaijan were ruled by the Kurdish dynasty of Shaddadid and Arab Radawids.

In the middle of the eleventh century, the Seljuq dynasty overthrew Arab rule and established an empire that encompassed most of Southwest Asia. The Seljuk period marked the influx of Oghuz nomads into the region. The emerging dominance of the Turkic language was chronicled in epic poems or dastans, the oldest being the Book of Dede Korkut, which relate allegorical tales about the early Turks in the Caucasus and Asia Minor.[2]: 45 Turkic dominion was interrupted by the Mongols in 1227, but it returned with the Timurids and then Sunni Qara Qoyunlū (Black Sheep Turkmen) and Aq Qoyunlū (White Sheep Turkmen), who dominated Azerbaijan, large parts of Iran, eastern Anatolia, and other minor parts of West Asia, until the Shi'a Safavids took power in 1501.[2]: 113 [87]: 285

Early modern period

The Safavids, who rose from around Ardabil in Iranian Azerbaijan and lasted until 1722, established the foundations of the modern Iranian state.[89] The Safavids, alongside their Ottoman archrivals, dominated the entire West Asian region and beyond for centuries. At its peak under Shah Abbas the Great, it rivaled its political and ideological archrival the Ottoman empire in military strength. Noted for achievements in state-building, architecture, and the sciences, the Safavid state crumbled due to internal decay (mostly royal intrigues), ethnic minority uprisings and external pressures from the Russians, and the eventually opportunistic Afghans, who would mark the end of the dynasty. The Safavids encouraged and spread Shi'a Islam, as well as the arts and culture, and Shah Abbas the Great created an intellectual atmosphere that according to some scholars was a new "golden age".[90] He reformed the government and the military and responded to the needs of the common people.[90]

After the Safavid state disintegrated, it was followed by the conquest by Nader Shah Afshar, a Shia chieftain from Khorasan who reduced the power of the ghulat Shi'a and empowered a moderate form of Shi'ism,[87]: 300 and, exceptionally noted for his military genius, making Iran reach its greatest extent since the Sassanid Empire. The brief reign of Karim Khan came next, followed by the Qajars, who ruled what is the present-day Azerbaijan Republic and Iran from 1779.[2]: 106 Russia loomed as a threat to Persian and Turkish holdings in the Caucasus in this period. The Russo-Persian Wars, despite already having had minor military conflicts in the 17th century, officially began in the eighteenth century and ended in the early nineteenth century with the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813 and the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828, which ceded the Caucasian portion of Qajar Iran to the Russian Empire.[55]: 17 While Azerbaijanis in Iran integrated into Iranian society, Azerbaijanis who used to live in Aran, were incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Despite the Russian conquest, throughout the entire 19th century, preoccupation with Iranian culture, literature, and language remained widespread amongst Shia and Sunni intellectuals in the Russian-held cities of Baku, Ganja and Tiflis (Tbilisi, now Georgia).[91] Within the same century, in post-Iranian Russian-held East Caucasia, an Azerbaijani national identity emerged at the end of the 19th century.[92] In 1891, the idea of recognizing oneself as a "Azerbaijani Turk" was first popularized amongst the Caucasus Tatars in the periodical Kashkül.[93] The articles printed in Kaspiy and Kashkül in 1891 are typically credited as being the earliest expressions of a cultural Azerbaijani identity.[94]

Modernisation—compared to the neighboring Armenians and Georgians—was slow to develop amongst the Tatars of the Russian Caucasus. According to the 1897 Russian Empire census, less than five percent of the Tatars were able to read or write. The intellectual and newspaper editor Ali bey Huseynzade (1864-1940) led a campaign to ‘Turkify, Islamise, modernise’ the Caucasian Tatars, whereas Mammed Said Ordubadi (1872-1950), another journalist and activist, criticized superstition amongst Muslims.[95]

Modern period in Republic of Azerbaijan

.gif)

.svg.png.webp)

After the collapse of the Russian Empire during World War I, the short-lived Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was declared, constituting what are the present-day republics of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia. This was followed by March Days massacres[97][98] that took place between 30 March and 2 April 1918 in the city of Baku and adjacent areas of the Baku Governorate of the Russian Empire.[99] When the republic dissolved in May 1918, the leading Musavat party adopted the name "Azerbaijan" for the newly established Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, which was proclaimed on 27 May 1918,[100] for political reasons,[101][102] even though the name of "Azerbaijan" had been used to refer to the adjacent region of contemporary northwestern Iran.[103][104] The ADR was the first modern parliamentary republic in the Turkic world and Muslim world.[97][105][106] Among the important accomplishments of the Parliament was the extension of suffrage to women, making Azerbaijan the first Muslim nation to grant women equal political rights with men.[105] Another important accomplishment of ADR was the establishment of Baku State University, which was the first modern-type university founded in Muslim East.[105]

By March 1920, it was obvious that Soviet Russia would attack the much-needed Baku. Vladimir Lenin said that the invasion was justified as Soviet Russia could not survive without Baku's oil.[107][108] Independent Azerbaijan lasted only 23 months until the Bolshevik 11th Soviet Red Army invaded it, establishing the Azerbaijan SSR on 28 April 1920. Although the bulk of the newly formed Azerbaijani army was engaged in putting down an Armenian revolt that had just broken out in Karabakh, Azeris did not surrender their brief independence of 1918–20 quickly or easily. As many as 20,000 Azerbaijani soldiers died resisting what was effectively a Russian reconquest.[109]

The brief independence gained by the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in 1918–1920 was followed by over 70 years of Soviet rule.[110]: 91 Neverthelesss, it was in the early Soviet period that the Azerbaijani national identity was finally forged.[92] After the restoration of independence in October 1991, the Republic of Azerbaijan became embroiled in a war with neighboring Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh region.[110]: 97

The First Nagorno-Karabakh War resulted in the displacement of approximately 725,000 Azerbaijanis and 300,000–500,000 Armenians from both Azerbaijan and Armenia.[111] As a result of 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Azerbaijan took back 5 cities, 4 towns, 286 villages in the region.[112] According to 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement, internally displaced persons and refugees shall return to the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent areas under the supervision of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.[113]

Modern period in Iran

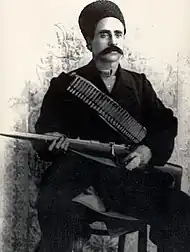

In Iran, Azerbaijanis such as Sattar Khan sought constitutional reform.[114] The Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906–11 shook the Qajar dynasty. A parliament (Majlis) was founded on the efforts of the constitutionalists, and pro-democracy newspapers appeared. The last Shah of the Qajar dynasty was soon removed in a military coup led by Reza Khan. In the quest to impose national homogeneity on a country where half of the population were ethnic minorities, Reza Shah banned in quick succession the use of the Azerbaijani language in schools, theatrical performances, religious ceremonies, and books.[115]

Upon the dethronement of Reza Shah in September 1941, Soviet forces took control of Iranian Azerbaijan and helped to set up the Azerbaijan People's Government, a client state under the leadership of Sayyid Jafar Pishevari backed by Soviet Azerbaijan. The Soviet military presence in Iranian Azerbaijan was mainly aimed at securing the Allied supply route during World War II. Concerned with the continued Soviet presence after World War II, the United States and Britain pressured the Soviets to withdraw by late 1946. Immediately thereafter, the Iranian government regained control of Iranian Azerbaijan. According to Professor Gary R. Hess, local Azerbaijanis favored the Iranian rule, while the Soviets forewent the Iranian Azerbaijan due to the exaggerated sentiment for autonomy and oil being their top priority.[116]

Origins

In many references, Azerbaijanis are designated as a Turkic people,[43][117] while some sources describe the origin of Azerbaijanis as "unclear",[118] mainly Caucasian,[119] mainly Iranian,[120][121] mixed Caucasian Albanian and Turkish,[122] and mixed with Caucasian, Iranian, and Turkic elements.[123] Russian historian and orientalist Vladimir Minorsky writes that largely Iranian and Caucasian populations became Turkic-speaking following the Oghuz occupation of the region, though the characteristic features of the local Turkic language, such as Persian intonations and disregard of the vocalic harmony, were a remnant of the non-Turkic population.[124]

Historical research suggests that the Old Azeri language, belonging to the Northwestern branch of the Iranian languages and believed to have descended from the language of the Medes,[125] gradually gained currency and was widely spoken in said region for many centuries.[126][127][128][129][130]

Some Azerbaijanis of the Republic of Azerbaijan are believed to be descended from the inhabitants of Caucasian Albania, an ancient country located in the eastern Caucasus region, and various Iranian peoples which settled the region.[131] They claim there is evidence that, due to repeated invasions and migrations, the aboriginal Caucasian population may have gradually been culturally and linguistically assimilated, first by Iranian peoples, such as the Persians,[132] and later by the Oghuz Turks. Considerable information has been learned about the Caucasian Albanians, including their language, history, early conversion to Christianity, and relations with the Armenians and Georgians, under whose strong religious and cultural influence the Caucasian Albanians came in the coming centuries.[133][134]

Turkic origin and Turkification

Turkification of the non-Turkic population derives from the Turkic settlements in the area now known as Azerbaijan, which began and accelerated during the Seljuk period.[43] The migration of Oghuz Turks from present-day Turkmenistan, which is attested by linguistic similarity, remained high through the Mongol period, as many troops under the Ilkhanates were Turkic. By the Safavid period, the Turkic nature of Azerbaijan increased with the influence of the Qizilbash, an association of the Turkoman[135] nomadic tribes that was the backbone of the Safavid Empire.

According to Soviet scholars, the Turkicization of Azerbaijan was largely completed during the Ilkhanid period. Faruk Sümer posits three periods in which Turkicization took place: Seljuk, Mongol and Post-Mongol (Qara Qoyunlu, Aq Qoyunlu and Safavid). In the first two, Oghuz Turkic tribes advanced or were driven to Anatolia and Arran. In the last period, the Turkic elements in Iran (Oghuz, with lesser admixtures of Uyghur, Qipchaq, Qarluq as well as Turkicized Mongols) were joined now by Anatolian Turks migrating back to Iran. This marked the final stage of Turkicization.[43]

Iranian origin

10th-century Arab historian Al-Masudi attested the Old Azeri language and described that the region of Azerbaijan was inhabited by Persians.[136] Archaeological evidence indicates that the Iranian religion of Zoroastrianism was prominent throughout the Caucasus before Christianity and Islam.[137][138][139] According to Encyclopaedia Iranica, Azerbaijanis mainly originate from the earlier Iranian speakers, who still exist to this day in smaller numbers, and a massive migration of Oghuz Turks in the 11th and 12th centuries gradually Turkified Azerbaijan as well as Anatolia.[140]

Caucasian origin

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, the Azerbaijanis are of mixed descent, originating in the indigenous population of eastern Transcaucasia and possibly the Medians from northern Iran.[141] There is evidence that, due to repeated invasions and migrations, aboriginal Caucasians may have been culturally assimilated, first by Ancient Iranian peoples and later by the Oghuz. Considerable information has been learned about the Caucasian Albanians including their language, history, early conversion to Christianity. The Udi language, still spoken in Azerbaijan, may be a remnant of the Albanians' language.[142]

Genetics

Contemporary Western Asian genomes, a region that includes Azerbaijan, have been greatly influenced by early agricultural populations in the area; later population movements, such as those of Turkic speakers, also contributed.[143] However, as of 2017, there is no whole genome sequencing study for Azerbaijan; sampling limitations such as these prevent forming a "finer-scale picture of the genetic history of the region".[143]

A 2014 study comparing the genetics of the populations from Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, (which were grouped as "Western Silk Road") Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan (grouped as "Eastern Silk Road") found that the samples from Azerbaijan were the only group from the Western Silk Road to show significant contribution from the Eastern Silk Road, despite the overall clustering with the other samples from the Western Silk Road. The eastern input into the Azerbaijani genetics was estimated to be roughly 25 generations ago, corresponding to the time of the Mongolian expansion.[144]

A 2002 study focusing on eleven Y-chromosome markers suggested that Azerbaijanis are genetically more related to their Caucasian geographic neighbors than to their linguistic neighbors.[145] Iranian Azerbaijanis are genetically more similar to northern Azerbaijanis and the neighboring Turkic population than they are to geographically distant Turkmen populations.[146] Iranian-speaking populations from Azerbaijan (the Talysh and Tats) are genetically closer to Azerbaijanis of the Republic than to other Iranian-speaking populations (Persian people and Kurds from Iran, Ossetians, and Tajiks).[147] Several genetic studies suggested that the Azerbaijanis originate from a native population long resident in the area who adopted a Turkic language through language replacement, including possibility of elite dominance scenario.[148][149][145] However, the language replacement in Azerbaijan (and in Turkey) might not have been in accordance with the elite dominance model, with estimated Central Asian contribution to Azerbaijan being 18% for females and 32% for males.[150] A subsequent study also suggested 33% Central Asian contribution to Azerbaijan.[151]

A 2001 study which looked into the first hypervariable segment of the MtDNA suggested that "genetic relationships among Caucasus populations reflect geographical rather than linguistic relationships", with Armenians and Azerbaijanians being "most closely related to their nearest geographical neighbours".[152] Another 2004 study that looked into 910 MtDNAs from 23 populations in the Iranian plateau, the Indus Valley, and Central Asia suggested that populations "west of the Indus basin, including those from Iran, Anatolia [Turkey] and the Caucasus, exhibit a common mtDNA lineage composition, consisting mainly of western Eurasian lineages, with a very limited contribution from South Asia and eastern Eurasia".[153] While genetic analysis of mtDNA indicates that Caucasian populations are genetically closer to Europeans than to Near Easterners, Y-chromosome results indicate closer affinity to Near Eastern groups.[145]

The range of haplogroups across the region may reflect historical genetic admixture,[154] perhaps as a result of invasive male migrations.[145]

In a comparative study (2013) on the complete mitochondrial DNA diversity in Iranians has indicated that Iranian Azeris are more related to the people of Georgia, than they are to other Iranians, as well as to Armenians. However the same multidimensional scaling plot shows that Azeris from the Caucasus, despite their supposed common origin with Iranian Azeris, "occupy an intermediate position between the Azeris/Georgians and Turks/Iranians grouping".[155]

A 2007 study which looked into class two Human leukocyte antigen suggested that there were "no close genetic relationship was observed between Azeris of Iran and the people of Turkey or Central Asians".[156] A 2017 study which looked into HLA alleles put the samples from Azeris in Northwest Iran "in the Mediterranean cluster close to Kurds, Gorgan, Chuvash (South Russia, towards North Caucasus), Iranians and Caucasus populations (Svan and Georgians)". This Mediterranean stock includes "Turkish and Caucasian populations". Azeri samples were also in a "position between Mediterranean and Central Asian" samples, suggesting Turkification "process caused by Oghuz Turkic tribes could also contribute to the genetic background of Azeri people".[157]

Demographics and society

The vast majority of Azerbaijanis live in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iranian Azerbaijan. Between 12 and 23 million Azerbaijanis live in Iran,[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] mainly in the northwestern provinces. Approximately 9.1 million Azerbaijanis are found in the Republic of Azerbaijan. A diaspora of over a million is spread throughout the rest of the world. According to Ethnologue, there are over 1 million speakers of the northern Azerbaijani dialect in southern Dagestan, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russian proper, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.[158] No Azerbaijanis were recorded in the 2001 census in Armenia,[159] where the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict resulted in population shifts. Other sources, such as national censuses, confirm the presence of Azerbaijanis throughout the other states of the former Soviet Union.

In the Republic of Azerbaijan

Azerbaijanis are by far the largest ethnic group in The Republic of Azerbaijan (over 90%), holding the second-largest community of ethnic Azerbaijanis after neighboring Iran. The literacy rate is very high, and is estimated at 99.5%.[160] Azerbaijan began the twentieth century with institutions based upon those of Russia and the Soviet Union, with an official policy of atheism and strict state control over most aspects of society. Since independence, there is a secular system.

Azerbaijan has benefited from the oil industry, but high levels of corruption have prevented greater prosperity for the population.[161] Despite these problems, there is a financial rebirth in Azerbaijan as positive economic predictions and an active political opposition appear determined to improve the lives of average Azerbaijanis.[162][163]

In Iran

The exact number of Azerbaijanis in Iran is heavily disputed. Since the early twentieth century, successive Iranian governments have avoided publishing statistics on ethnic groups.[164] Unofficial population estimates of Azerbaijanis in Iran are around the 16% area put forth by the CIA and Library of Congress.[165][166] An independent poll in 2009 placed the figure at around 20–22%.[167] According to the Iranologist Victoria Arakelova in peer-reviewed journal Iran and the Caucasus, estimating the number of Azeris in Iran has been hampered for years since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when the "once invented theory of the so called separated nation (i.e. the citizens of the Azerbaijan Republic, the so-called Azerbaijanis, and the Azaris in Iran), was actualised again (see in detail Reza 1993)". Arakelova adds that the number of Azeris in Iran, featuring in the politically biased publications as "Azerbaijani minority of Iran", is considered to be the "highly speculative part of this theory". Even though all Iranian censuses of population distinguish exclusively religious minorities, numerous sources have presented different figures regarding Iran's Turkic-speaking communities, without "any justification or concrete references".[168]

In the early 1990s, right after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the most popular figure depicting the number of "Azerbaijanis" in Iran was thirty-three million, at a time when the entire population of Iran was barely sixty million. Therefore, at the time, half of Iran's citizens were considered "Azerbaijanis". Shortly after, this figure was replaced by thirty million, which became "almost a normative account on the demographic situation in Iran, widely circulating not only among academics and political analysts, but also in the official circles of Russia and the West". Then, in the 2000s, the figure decreased to 20 million; this time, at least within the Russian political establishment, the figure became "firmly fixed". This figure, Arakelova adds, has been widely used and kept up to date, only with a few minor adjustments. A cursory look at Iran's demographic situation however, shows that all these figures have been manipulated and were "definitely invented on political purpose". Arakelova estimates the number of Azeris i.e. "Azerbaijanis" in Iran based on Iran's population demographics at 6 to 6.5 million.[168]

Azerbaijanis in Iran are mainly found in the northwest provinces: West Azerbaijan, East Azerbaijan, Ardabil, Zanjan, parts of Hamadan, Qazvin, and Markazi.[166] Azerbaijani minorities live in the Qorveh[169] and Bijar[170] counties of Kurdistan, in Gilan,[171][172][173][174] as ethnic enclaves in Galugah in Mazandaran, around Lotfabad and Dargaz in Razavi Khorasan,[175] and in the town of Gonbad-e Qabus in Golestan.[176] Large Azerbaijani populations can also be found in central Iran (Tehran # Alborz) due to internal migration. Azerbaijanis make up 25%[177] of Tehran's population and 30.3%[178] – 33%[179][180] of the population of the Tehran Province, where Azerbaijanis are found in every city.[181] They are the largest ethnic groups after Persians in Tehran and the Tehran Province.[182][183] Arakelova notes that the widespread "cliché" among residents of Tehran on the number of Azerbaijanis in the city ("half of Tehran consists of Azerbaijanis"), cannot be taken "seriously into consideration". Arakelova adds that the number of Tehran's inhabitants who have migrated from northwestern areas of Iran, who are currently Persian-speakers "for the most part", is not more than "several hundred thousands", with the maximum being one million.[168] Azerbaijanis have also emigrated and resettled in large numbers in Khorasan,[184] especially in Mashhad.[185]

Generally, Azerbaijanis in Iran were regarded as "a well integrated linguistic minority" by academics prior to Iran's Islamic Revolution.[186][187] Despite friction, Azerbaijanis in Iran came to be well represented at all levels of "political, military, and intellectual hierarchies, as well as the religious hierarchy".[164]

Resentment came with Pahlavi policies that suppressed the use of the Azerbaijani language in local government, schools, and the press.[188] However, with the advent of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, emphasis shifted away from nationalism as the new government highlighted religion as the main unifying factor. Islamic theocratic institutions dominate nearly all aspects of society. The Azerbaijani language and its literature are banned in Iranian schools.[189][190] There are signs of civil unrest due to the policies of the Iranian government in Iranian Azerbaijan and increased interaction with fellow Azerbaijanis in Azerbaijan and satellite broadcasts from Turkey and other Turkic countries have revived Azerbaijani nationalism.[191] In May 2006, Iranian Azerbaijan witnessed riots over publication of a cartoon depicting a cockroach speaking Azerbaijani[192] that many Azerbaijanis found offensive.[193][194] The cartoon was drawn by Mana Neyestani, an Azeri, who was fired along with his editor as a result of the controversy.[195][196] One of the major incidents that happened recently was Azeris protests in Iran (2015) started in November 2015, after children's television programme Fitileha aired on 6 November on state TV that ridiculed and mocked the accent and language of Azeris and included offensive jokes.[197] As a result, hundreds of ethnic Azeris have protested a program on state TV that contained what they consider an ethnic slur. Demonstrations were held in Tabriz, Urmia, Ardabil, and Zanjan, as well as Tehran and Karaj. Police in Iran have clashed with protesting people, fired tear gas to disperse crowds, and many demonstrators were arrested. One of the protesters, Ali Akbar Murtaza, reportedly "died of injuries" in Urmia.[198] There were also protests held in front of Iranian embassies in Istanbul and Baku.[199] The head of the country's state broadcaster Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) Mohammad Sarafraz has apologized for airing the program, whose broadcast was later discontinued.[200]

Azerbaijanis are an intrinsic community of Iran, and their style of living closely resemble those of Persians:

The lifestyles of urban Azerbaijanis do not differ from those of Persians, and there is considerable intermarriage among the upper classes in cities of mixed populations. Similarly, customs among Azerbaijani villagers do not appear to differ markedly from those of Persian villagers.[166]

Azeris are famously active in commerce and in bazaars all over Iran their voluble voices can be heard. Older Azeri men wear the traditional wool hat, and their music & dances have become part of the mainstream culture. Azeris are well integrated, and many Azeri-Iranians are prominent in Persian literature, politics, and clerical world.[201]

There is significant cross-border trade between Azerbaijan and Iran, and Azerbaijanis from Azerbaijan go into Iran to buy goods that are cheaper, but the relationship was tense until recently.[189] However, relations have significantly improved since the Rouhani administration took office.

Subgroups

There are several Azerbaijani ethnic groups, each of which has particularities in the economy, culture, and everyday life. Some Azerbaijani ethnic groups continued in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Major Azerbaijani ethnic groups:

Diaspora

Women

In Azerbaijan, women were granted the right to vote in 1917.[203] Women have attained Western-style equality in major cities such as Baku, although in rural areas more reactionary views remain.[162] Violence against women, including rape, is rarely reported, especially in rural areas, not unlike other parts of the former Soviet Union.[204] In Azerbaijan, the veil was abandoned during the Soviet period.[205] Women are under-represented in elective office but have attained high positions in parliament. An Azerbaijani woman is the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in Azerbaijan, and two others are Justices of the Constitutional Court. In the 2010 election, women constituted 16% of all MPs (twenty seats in total) in the National Assembly of Azerbaijan.[206] Abortion is available on demand in the Republic of Azerbaijan.[207] The human rights ombudsman since 2002, Elmira Süleymanova, is a woman.

In Iran, a groundswell of grassroots movements have sought gender equality since the 1980s.[166] Protests in defiance of government bans are dispersed through violence, as on 12 June 2006 when female demonstrators in Haft Tir Square in Tehran were beaten.[208] Past Iranian leaders, such as the reformer ex-president Mohammad Khatami promised women greater rights, but the Guardian Council of Iran opposes changes that they interpret as contrary to Islamic doctrine. In the 2004 legislative elections, nine women were elected to parliament (Majlis), eight of whom were conservatives.[209] The social fate of Azerbaijani women largely mirrors that of other women in Iran.

Culture

Language and literature

The Azerbaijanis speak the Azerbaijani language, a Turkic language descended from the branches of Oghuz Turkic language that became established in Azerbaijan in the 11th and 12th centuries CE. The Azerbaijani language is closely related to Qashqai, Gagauz, Turkish, Turkmen and Crimean Tatar, sharing varying degrees of mutual intelligibility with each of those languages.[211] Certain lexical and grammatical differences formed within the Azerbaijani language as spoken in the Republic of Azerbaijan and Iran, after nearly two centuries of separation between the communities speaking the language; mutual intelligibility, however, has been preserved.[212] Additionally, the Turkish and Azerbaijani languages are mutually intelligible to a high enough degree that their speakers can have simple conversations without prior knowledge of the other.[110]

Early literature was mainly based on oral tradition, and the later compiled epics and heroic stories of Dede Korkut probably derive from it. The first written, classical Azerbaijani literature arose after the Mongol invasion, while the first accepted Oghuz Turkic text goes back to the 15th century.[213] Some of the earliest Azerbaijani writings trace back to the poet Nasimi (died 1417) and then decades later Fuzûlî (1483–1556). Ismail I, Shah of Safavid Iran wrote Azerbaijani poetry under the pen name Khatâ'i.

Modern Azerbaijani literature continued with a traditional emphasis upon humanism, as conveyed in the writings of Samad Vurgun, Shahriar, and many others.[214]

Azerbaijanis are generally bilingual, often fluent in either Russian (in Azerbaijan) or Persian (in Iran) in addition to their native Azerbaijani. As of 1996, around 38% of Azerbaijan's roughly 8,000,000 population spoke Russian fluently.[215] An independent telephone survey in Iran in 2009 reported that 20% of respondents could understand Azerbaijani, the most spoken minority language in Iran, and all respondents could understand Persian.[167]

Religion

The majority of Azerbaijanis are Twelver Shi'a Muslims. Religious minorities include Sunni Muslims (mainly Shafi'i just like other Muslims in the surrounding North Caucasus),[216][217] and Baháʼís. An unknown number of Azerbaijanis in the Republic of Azerbaijan have no religious affiliation. Many describe themselves as Shia Muslims.[162] There is a small number of Naqshbandi Sufis among Muslim Azerbaijanis.[218] Christian Azerbaijanis number around 5,000 people in the Republic of Azerbaijan and consist mostly of recent converts.[219][220] Some Azerbaijanis from rural regions retain pre-Islamic animist or Zoroastrian-influenced[221] beliefs, such as the sanctity of certain sites and the veneration of fire, certain trees and rocks.[222] In Azerbaijan, traditions from other religions are often celebrated in addition to Islamic holidays, including Nowruz and Christmas.

Performing arts

In the group dance the performers come together in a semi-circular or circular formation as, "The leader of these dances often executes special figures as well as signaling and changes in the foot patterns, movements, or direction in which the group is moving, often by gesturing with his or her hand, in which a kerchief is held."[223]

Azerbaijani musical tradition can be traced back to singing bards called Ashiqs, a vocation that survives. Modern Ashiqs play the saz (lute) and sing dastans (historical ballads).[224] Other musical instruments include the tar (another type of lute), balaban (a wind instrument), kamancha (fiddle), and the dhol (drums). Azerbaijani classical music, called mugham, is often an emotional singing performance. Composers Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Gara Garayev and Fikret Amirov created a hybrid style that combines Western classical music with mugham. Other Azerbaijanis, notably Vagif and Aziza Mustafa Zadeh, mixed jazz with mugham. Some Azerbaijani musicians have received international acclaim, including Rashid Behbudov (who could sing in over eight languages), Muslim Magomayev (a pop star from the Soviet era), Googoosh, and more recently Sami Yusuf.

After the 1979 revolution in Iran due to the clerical opposition to music in general, Azerbaijani music took a different course. According to Iranian singer Hossein Alizadeh, "Historically in Iran, music faced strong opposition from the religious establishment, forcing it to go underground."[225]

Some Azerbaijanis have been film-makers, such as Rustam Ibragimbekov, who wrote Burnt by the Sun, winner of the Grand Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1994.

Sports

Sports have historically been an important part of Azerbaijani life. Horseback competitions were praised in the Book of Dede Korkut and by poets and writers such as Khaqani.[226] Other ancient sports include wrestling, javelin throwing and fencing.

The Soviet legacy has in modern times propelled some Azerbaijanis to become accomplished athletes at the Olympic level.[226] The Azerbaijani government supports the country's athletic legacy and encourages youth participation. Iranian athletes have particularly excelled in weight lifting, gymnastics, shooting, javelin throwing, karate, boxing, and wrestling.[227] Weight lifters, such as Iran's Hossein Reza Zadeh, world super heavyweight-lifting record holder and two-time Olympic champion in 2000 and 2004, or Hadi Saei is a former Iranian[228] Taekwondo athlete who became the most successful Iranian athlete in Olympic history and Nizami Pashayev, who won the European heavyweight title in 2006, have excelled at the international level. Ramil Guliyev, an ethnic Azerbaijani who plays for Turkey, became the first world champion in athletics in the history of Turkey.

Chess is another popular pastime in the Republic of Azerbaijan.[229] The country has produced many notable players, such as Teimour Radjabov, Vugar Gashimov and Shahriyar Mammadyarov, all three highly ranked internationally. Karate is also popular, where Rafael Aghayev achieved particular success, becoming a five-time world champion and eleven-time European champion.

References

Citations

- Sela, Avraham (2002). The Continuum Political Encyclopedia of the Middle East. Continuum. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-8264-1413-7.

They number 30-35 million and live primarily in Iran (approximately 20 million) , the Republic of Azerbaijan (8 million), Turkey (1-2 million), Russia (1 million), and Georgia (300,000).

- Swietochowski & Collins (1999, p. 165): Today, Iranian Azerbaijan has a solid majority of Azeris with an estimated population of at least 15 million (over twice the population of the Azerbaijani Republic). (1999)

- "Iran". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

Ethnic population: 16,700,000 (2019)

- Elling, Rasmus Christian (18 February 2013). Minorities in Iran: Nationalism and Ethnicity after Khomeini. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-137-04780-9.

CIA and Library of Congress estimates range from 16 percent to 24 percent—that is, 12–18 million people if we employ the latest total figure for Iran's population (77.8 million).

- Gheissari, Ali (2 April 2009). Contemporary Iran: Economy, Society, Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-19-988860-3.

As of 2003, the ethnic classifications are estimated as: [...] Azeri (24 percent)

- Bani-Shoraka, Helena (1 July 2009). "Cross-generational bilingual strategies among Azerbaijanis in Tehran". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 2009 (198): 106. doi:10.1515/IJSL.2009.029. ISSN 1613-3668. S2CID 144993160.

The latest figures estimate the Azerbaijani population at 24% of Iran's 70 million inhabitants (NVI 2003/2004: 301). This means that there are between 15 and 20 million Azerbaijanis in Iran.

- Potter, Lawrence G. (2014). Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf. Oxford University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-19-937726-8. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Crane, Keith; Lal, Rollie; Martini, Jeffrey (6 June 2008). Iran's Political, Demographic, and Economic Vulnerabilities. RAND Corporation. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8330-4527-0. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- Moaddel, Mansoor; Karabenick, Stuart A. (4 June 2013). Religious Fundamentalism in the Middle East: A Cross-National, Inter-Faith, and Inter-Ethnic Analysis. Brill. p. 101.

The Azeris have a mixed heritage of Iranic, Caucasian, and Turkic elements(...) Between 16 to 23 million Azeris live in Iran.

- Eschment, Beate; von Löwis, Sabine, eds. (18 August 2022). Post-Soviet Borders: A Kaleidoscope of Shifting Lives and Lands. Taylor & Francis. p. 31.

Irrespective of the large Azerbaijani population in Iran (about 20 million, compared to 7 million in Azerbaijan)(...)

- Azerbaijan Republic | Population by ethnic groups stat.gov.az

- "Итоги переписи". 2010 census. Russian Federation State Statistics Service. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- van der Leeuw, Charles (2000). Azerbaijan: a quest for identity : a short history. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-312-21903-1. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- "Ethnic groups by major administrative-territorial units" (PDF). 2014 census. National Statistics Office of Georgia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2020 года". Комитет по статистике Министерства национальной экономики Республики Казахстан. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "The National Structure of the Republic of Uzbekistan". Umid World. 1989. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР. Демоскоп Weekly (in Russian) (493–494). 1–22 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "Azerbaijani-American Council rpartners with U.S. Census Bureau". News.Az. 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- http://www.azeris.org/images/proclamations/May28_BrooklynNY_2011.JPG%5B%5D

- "Obama, recognize us – St. Louis American: Letters To The Editor". Stlamerican.com. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- "A portrait of a migrant: Azerbaijanis in Germany". boell.de. HEINRICH-BÖLL-STIFTUNG – The Green Political Foundation. 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "The Kingdom of the Netherlands: Bilateral relations: Diaspora" (PDF). Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "5.01.00.03 Национальный состав населения" (PDF) (in Russian). National Statistical Committee of Kyrgyz Republic. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- İlhamqızı, Sevda (2 October 2007). "Gələn ilin sonuna qədər dünyada yaşayan azərbaycanlıların sayı və məskunlaşma coğrafiyasına dair xəritə hazırlanacaq". Trend News Agency (in Azerbaijani). Baku. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Canada Census Profile 2021". Census Profile, 2021 Census. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- "Estrangeiros em Portugal" (PDF).

- "Azerbaijani diaspora".

- "Azeris abroad".

- "UAE´s population – by nationality". BQ Magazine. 12 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- "Nationality and country of birth by age, sex and qualifications Jan – Dec 2013 (Excel sheet 60Kb)". www.ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- "Population Census 2009" (PDF). National Statistical Committee of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Foreign born after country of birth and immigration year". Statistics Sweden.

- "Population by ethnicity at the beginning of year – Time period and Ethnicity | National Statistical System of Latvia". data.stat.gov.lv.

- "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības, 01.01.2023. - PMLP".

- Azerbaijan country brief Archived 18 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine. NB According to the 2016 census, 1,036 people living in Australia identified themselves as of Azeri ancestry. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "The Republic of Austria: Bilateral relations" (PDF). Republic of Azerbaijan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- "Population Census of 2011". Statistics Estonia. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018. Select "Azerbaijani" under "Ethnic nationality".

- "2020-03-09". ssb.no. 9 March 2020. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "Population by ethnicity in 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989, 2001 and 2011". Lithuanian Department of Statistics. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- http://demo.istat.it/str2019/index.html ISTAT – Foreign resident population in 2019

- Robertson, Lawrence R. (2002). Russia & Eurasia Facts & Figures Annual. Academic International Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-87569-199-2. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples. Otto Harrasowitz. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2.

- Ismail Zardabli. Ethnic and political history of Azerbaijan. Rossendale Books. 2018. p.35 "... the ancestors of Azerbaijanis and Turkmens are the tribes that lived in these territories."

- MacCagg, William O.; Silver, Brian D. (10 May 1979). Soviet Asian ethnic frontiers. Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-024637-6. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2020 – via Google Books.

- Binder, Leonard (10 May 1962). "Iran: Political Development in a Changing Society". University of California Press. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- Hobbs, Joseph J. (13 March 2008). World Regional Geography. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-38950-7. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- "2014 General Population Census" (PDF). National Statistics Office of Georgia. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Harcave, Sidney (1968). Russia: A History: Sixth Edition. Lippincott. p. 267.

- Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (2007). Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbors in the Middle East by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field. Universal. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-58112-933-5.

- Lendering, Jona. "Atropates (Biography)". Livius.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Chamoux, Francois (2003). Hellenistic Civilization. Blackwell Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-631-22241-5.

- Bosworth, A. B.; Baynham, E. J. (2002). Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-815287-3.

- Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. I. B. Tauris. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-86064-554-9. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Altstadt, Audrey L. (1992). The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity under Russian Rule. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-9182-1.

- Chaumont 1987, pp. 17–18.

- MacKenzie, D. (1971). A concise Pahlavi dictionary (p. 5, 8, 18). London: Oxford university press.

- de Planhol 2004, pp. 205–215.

- Schippmann, K. (15 December 1987). "Azerbaijan, Pre-Islamic History". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- "Azerbaijan". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Aliyev, Igrar. (1958). History of Atropatene (تاريخ آتورپاتكان) (p. 93).

- EI. (1989). "AZERBAIJAN". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume III: Ātaš–Bayhaqī, Ẓahīr-al-Dīn. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 205–257. ISBN 978-0-71009-121-5.

- Kemp, Geoffrey; Stein, Janice Gross (1995). Powder Keg in the Middle East. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-8476-8075-7.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur. "18. 1886–1890: An Ethnolinguistic Map of the Caucasus". Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, pp. 48–50. "“Tatars” (or in rarer cases, “Azerbaijani Tatars”) to denote Turkic-speaking Transcaucasian populations that would later be called “Azerbaijanis”"

- Yilmaz, Harun (2013). "The Soviet Union and the Construction of Azerbaijani National Identity in the 1930s". Iranian Studies. 46 (4): 513. doi:10.1080/00210862.2013.784521. S2CID 144322861.

The official records of the Russian Empire and various published sources from the pre-1917 period also called them "Tatar" or "Caucasian Tatars," "Azerbaijani Tatars" and even "Persian Tatars" in order to differentiate them from the other "Tatars" of the empire and the Persian speakers of Iran.

- Алфавитный список народов, обитающих в Российской Империи (in Russian). Demoscope Weekly. 2005. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Тюрки. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1890–1907. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Тюрко-татары. Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1890–1907. Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Deniker, Joseph (1900). Races et peuples de la terre (in French). Paris, France: Schleicher frères. p. 349. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

Ce groupement ne coïncide pas non-plus avec le groupement somatologique : ainsi, les Aderbaïdjani du Caucase et de la Perse, parlant une langue turque, ont le mème type physique que les Persans-Hadjemi, parlant une langue iranienne.

- Mostashari, Firouzeh (2006). On the Religious Frontier: Tsarist Russia and Islam in the Caucasus. I. B. Tauris. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-85043-771-0. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur. "Appendix 3: Ethnic Composition of the Caucasus: Historical Population Statistics". Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, p. 192 (note 150).

- Tsutsiev, Arthur. "31. 1926: An Ethnic Map Reflecting the First Soviet Census". Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, p. 87.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur. "26. 1920: The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and Soviet Russia". Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, pp. 71–73.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur. "32. 1926: Using the Census to Identify Russians and Ukrainians". Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014, pp. 87–90

- "AZERBAIJAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2–3. 1987. pp. 205–257.

- Kurkiev 1979, p. 190.

- Akhriev 1975, p. 203.

- Yarshater, E (18 August 2011). "The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Bosworth, C. E. (12 August 2011). "Arran". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Roy, Olivier (2007). The new Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter was to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkified' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.

- Coene, Frederik (2010). The Caucasus: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-415-48660-6.

- "Countries and Territories of the World". Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Armenia-Ancient Period". Federal Research Division Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Chaumont, M. L. (29 July 2011). "Albania". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Alexidze, Zaza (Summer 2002). "Voices of the Ancients: Heyerdahl Intrigued by Rare Caucasus Albanian Text". Azerbaijan International. 10 (2): 26–27. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- "Sassanid Empire". The Islamic World to 1600. University of Calgary. 1998. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Lapidus, Ira (1988). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1992). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Longman. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- "The Safavid Empire". University of Calgary. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- Sammis, Kathy (2002). Focus on World History: The First Global Age and the Age of Revolution. J. Weston Walch. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8251-4370-0.

- Gasimov, Zaur (2022). "Observing Iran from Baku: Iranian Studies in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan". Iranian Studies. 55 (1): 38. doi:10.1080/00210862.2020.1865136. S2CID 233889871.

The preoccupation with Iranian culture, literature, and language was widespread among Baku-, Ganja-, and Tiflis-based Shia as well as Sunni intellectuals, and it never ceased throughout the nineteenth century.

- Gasimov, Zaur (2022). "Observing Iran from Baku: Iranian Studies in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan". Iranian Studies. 55 (1): 37. doi:10.1080/00210862.2020.1865136. S2CID 233889871.

Azerbaijani national identity emerged in post-Persian Russian-ruled East Caucasia at the end of the nineteenth century, and was finally forged during the early Soviet period.

- Bishku, Michael B. (2022). "The Status and Limits to Aspirations of Minorities in the South Caucasus States". Contemporary Review of the Middle East. 9 (4): 414. doi:10.1177/23477989221115917. S2CID 251777404.

- Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinburgh University Press. p. 326 (note 9). ISBN 978-1-4744-5052-2.

- Pourjavady, R. (2023). "Introduction: Iran, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia in the 19th century". In Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A. (eds.). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 20. Iran, Afghanistan and the Caucasus (1800-1914). Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. p. 20.

- Азербайджанская Демократическая Республика (1918―1920). Законодательные акты. (Сборник документов). — Баку, 1998, С.188

- Russia and a Divided Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition, by Tadeusz Świętochowski, Columbia University Press, 1995, p. 66

- Smith, Michael (April 2001). "Anatomy of Rumor: Murder Scandal, the Musavat Party and Narrative of the Russian Revolution in Baku, 1917–1920". Journal of Contemporary History. 36 (2): 228. doi:10.1177/002200940103600202. S2CID 159744435.

The results of the March events were immediate and total for the Musavat. Several hundreds of its members were killed in the fighting; up to 12,000 Muslim civilians perished; thousands of others fled Baku in a mass exodus

- Michael Smith. "Pamiat' ob utratakh i Azerbaidzhanskoe obshchestvo/Traumatic Loss and Azerbaijani. National Memory". Azerbaidzhan i Rossiia: obshchestva i gosudarstva (Azerbaijan and Russia: Societies and States) (in Russian). Sakharov Center. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Atabaki, Touraj (2006). Iran and the First World War: Battleground of the Great Powers'. I.B.Tauris. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-86064-964-6. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Yilmaz, Harun (2015). National Identities in Soviet Historiography: The Rise of Nations Under Stalin. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-317-59664-6.

On May 27, the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (DRA) was declared with Ottoman military support. The rulers of the DRA refused to identify themselves as [Transcaucasian] Tatar, which they rightfully considered to be a Russian colonial definition. (...) Neighboring Iran did not welcome the DRA's adoption of the name of "Azerbaijan" for the country because it could also refer to Iranian Azerbaijan and implied a territorial claim.

- Barthold, Vasily (1963). Sochineniya, vol II/1. Moscow. p. 706.

(...) whenever it is necessary to choose a name that will encompass all regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan, name Arran can be chosen. But the term Azerbaijan was chosen because when the Azerbaijan republic was created, it was assumed that this and the Persian Azerbaijan will be one entity because the population of both has a big similarity. On this basis, the word Azerbaijan was chosen. Of course right now when the word Azerbaijan is used, it has two meanings as Persian Azerbaijan and as a republic, its confusing and a question arises as to which Azerbaijan is talked about.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-86064-554-9.

- Rezvani, Babak (2014). Ethno-territorial conflict and coexistence in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Fereydan: academisch proefschrift. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-90-485-1928-6.

The region to the north of the river Araxes was not called Azerbaijan prior to 1918, unlike the region in northwestern Iran that has been called since so long ago.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia: 1917–1921. The New York Philosophical Library. pp. 124, 222, 229, 269–270. ISBN 978-0-8305-0076-5.

- Schulze, Reinhard (2000). A Modern History of the Islamic World. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9.

- Горянин, Александр (28 August 2003). Очень черное золото (in Russian). GlobalRus. Archived from the original on 6 September 2003. Retrieved 28 August 2003.

- Горянин, Александр. История города Баку. Часть 3. (in Russian). Window2Baku. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Pope, Hugh (2006). Sons of the conquerors: the rise of the Turkic world. New York: The Overlook Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-58567-804-4.

- Nichol, James (1995). "Azerbaijan". In Curtis, Glenn E. (ed.). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0848-4. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- Haider, Hans (2 January 2013). "Gefährliche Töne im "Frozen War"". Wiener Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- "İşğaldan azad edilmiş şəhər və kəndlərimiz". Azerbaijan State News Agency (in Azerbaijani). 1 December 2020. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- "Statement by President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia and President of the Russian Federation". Kremlin.ru. 10 November 2020.

- Pistor-Hatam, Anja (20 July 2009). "Sattār Khan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- Hess, Gary. R. (March 1974). "The Iranian Crisis of 1945–46 and the Cold War" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. 89 (1): 117–146. doi:10.2307/2148118. JSTOR 2148118. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "Turkic Peoples". Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 27. Grolier. 1998. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-7172-0130-3.

- Anna Matveeva (2002). The South Caucasus:Nationalism, Conflict and Minorities (PDF) (Report). Minority Rights Group International. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

The ethnic origins of the Azeris are unclear. The prevailing view is that Azeris are a Turkic people, but there is also a claim that Azeris are Turkicized Caucasians or, as the Iranian official history claims, Turkicized Aryans.

- Kobishchanov, Yuri M. (1979). Axum. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-271-00531-7. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Roy, Olivier (2007). The new Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4. "The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateaux, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter was to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkified' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris."

- Frye, R. N. (15 December 2004). "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN (1) A General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- Suny, Ronald G. (July–August 1988). "What Happened in Soviet Armenia?". Middle East Report (153, Islam and the State): 37–40. doi:10.2307/3012134. JSTOR 3012134. "The Albanians in the eastern plain leading down to the Caspian Sea mixed with the Turkish population and eventually became Muslims." "...while the eastern Transcaucasian countryside was home to a very large Turkic-speaking Muslim population. The Russians referred to them as Tartars, but we now consider them Azerbaijanis, a distinct people with their own language and culture."

- Svante E. Cornell (20 May 2015). Azerbaijan Since Independence. Routledge. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1-317-47621-4. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015. "If native Caucasian, Iranian, and Turkic populations – among others – dominated Azerbaijan from the fourth century CE onwards, the Turkic element would grow increasingly dominant in linguistic terms,5 while the Persian element retained strong cultural and religious influence." "Following the Seljuk great power period, the Turkic element in Azerbaijan was further strengthened by migrations during the Mongol onslaught of the thirteenth century and the subsequent domination by the Turkmen Qaraqoyunlu and Aq-qoyunlu dynasties."

- Minorsky, V. "Azarbaijan". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill.

- The Iranian languages. Windfuhr, Gernot. London: Routledge. 2009. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4. OCLC 312730458.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Planhol, Xavier de. "IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. pp. 204–212. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Frye, R. N. "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN (1) A General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. pp. 321–326. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Minorsky, V. "Azerbaijan". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; Donzel, E. van; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill.

- Roy, Olivier (2007). The new Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-84511-552-4. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

The mass of the Oghuz who crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves more to the west, in Anatolia. Here they divided into Ottomans, who were Sunni and settled, and Turkmens, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi). The latter were to keep the name 'Turkmen' for a long time: from the 13th century onwards they 'Turkised' the Iranian populations of Azerbaijan (who spoke west Iranian languages such as Tat, which is still found in residual forms), thus creating a new identity based on Shiism and the use of Turkish. These are the people today known as Azeris.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (15 December 1988). "AZERBAIJAN vii. The Iranian Language of Azerbaijan". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- Sourdel, D. (1959). "V. MINORSKY, A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th–11th centuries, 1 vol. in-8°, 187 p. et 32 p. (texte arabe), Cambridge (Heffer and Sons), 1958". Arabica. 6 (3): 326–327. doi:10.1163/157005859x00208. ISSN 0570-5398.

- Istorii︠a︡ Vostoka : v shesti tomakh. Rybakov, R. B., Kapit︠s︡a, Mikhail Stepanovich., Рыбаков, Р. Б., Капица, Михаил Степанович., Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡ (Rossiĭskai︠a︡ akademii︠a︡ nauk), Институт востоковедения (Rossiĭskai︠a︡ akademii︠a︡ nauk). Moskva: Izdatelʹskai︠a︡ firma "Vostochnai︠a︡ lit-ra" RAN. 1995–2008. ISBN 5-02-018102-1. OCLC 38520460.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Weitenberg, J.J.S. (1984). "Thomas J. SAMUELIAN (ed.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity. Proceedings of the first Dr. H. Markarian Conference on Armenian culture (University of Pennsylvania Armenian Texts and Studies 4), Scholars Press, Chico, CA 1982, xii and 233 pp., paper $ 15,75 (members $ 10,50), cloth $ 23,50 (members $ 15,75)". Journal for the Study of Judaism. 15 (1–2): 198–199. doi:10.1163/157006384x00411. ISSN 0047-2212.

- Suny, Ronald G.; Stork, Joe (July 1988). "Ronald G. Suny: What Happened in Soviet Armenia?". Middle East Report (153): 37–40. doi:10.2307/3012134. ISSN 0899-2851. JSTOR 3012134.

- David Blow. Shah Abbas: The Ruthless King Who Became an Iranian Legend. p. 165. "The primary court language remained Turkish. But it was not the Turkish of Istambul. It was a Turkish dialect, the dialect of the Qizilbash Turkomans..."

- Al Mas'udi (1894). De Goeje, M.J. (ed.). Kitab al-Tanbih wa-l-Ishraf (in Arabic). Brill. pp. 77–78. Arabic text: "قد قدمنا فيما سلف من كتبنا ما قاله الناس في بدء النسل، وتفرقهم على وجه الأرض، وما ذهب إليه كل فريق منهم في ذلك من الشرعيين وغيرهم ممن قال بحدوث العالم وأبى الانقياد إلى الشرائع من البراهمة وغيرهم، وما قاله أصحاب القدم في ذلك من الهند والفلاسفة وأصحاب الاثنين من المانوية وغيرهم على تباينهم في ذلك، فلنذكر الآن الأمم السبع ذهب من عني بأخبار سوالف الأمم ومساكنهم إلى أن أجل الأمم وعظماءهم كانوا في سوالف الدهر سبعاً يتميزون بثلاثة أشياء: بشيمهم الطبيعية، وخلقهم الطبيعية، وألسنتهم فالفرس أمة حد بلادها الجبال من الماهات وغيرها وآذربيجان إلى ما يلي بلاد أرمينية وأران والبيلقان إلى دربند وهو الباب والأبواب والري وطبرستن والمسقط والشابران وجرجان وابرشهر، وهي نيسابور، وهراة ومرو وغير ذلك من بلاد خراسان وسجستان وكرمان وفارس والأهواز، وما اتصل بذلك من أرض الأعاجم في هذا الوقت وكل هذه البلاد كانت مملكة واحدة ملكها ملك واحد ولسانها واحد، إلا أنهم كانوا يتباينون في شيء يسير من اللغات."

- "Various Zoroastrian Fire-Temples". University of Calgary. 1 February 2000. Archived from the original on 30 April 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2006.

- Geukjian, Ohannes (2012). Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict in the South Caucasus. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-3630-0. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Suny, Ronald G. (April 1996). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. DIANE Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7881-2813-4. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Frye, R. N. (15 December 2004). "Peoples of Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Azerbaijani (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Schulze, Wolfgang (2001–2002). "The Udi Language". University of Munich. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Taskent RO, Gokcumen O (2017). "The Multiple Histories of Western Asia: Perspectives from Ancient and Modern Genomes". Hum Biol. 89 (2): 107–117. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.89.2.01. PMID 29299965. S2CID 6871226.

- Mezzavilla, Massimo; Vozzi, Diego; Pirastu, Nicola; Girotto, Giorgia; d’Adamo, Pio; Gasparini, Paolo; Colonna, Vincenza (5 December 2014). "Genetic landscape of populations along the Silk Road: admixture and migration patterns". BMC Genetics. 15 (1): 131. doi:10.1186/s12863-014-0131-6. ISSN 1471-2156. PMC 4267745. PMID 25476266.

- Nasidze, Ivan; Sarkisian, Tamara; Kerimov, Azer; Stoneking, Mark (2003). "Testing hypotheses of language replacement in the Caucasus" (PDF). Human Genetics. 112 (3): 255–261. doi:10.1007/s00439-002-0874-4. PMID 12596050. S2CID 13232436. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 March 2007.

- Andonian l.; et al. (2011). "Iranian Azeri's Y-Chromosomal Diversity in the Context of Turkish-Speaking Populations of the Middle East" (PDF). Iranian J Publ Health. 40 (1): 119–123. PMC 3481719. PMID 23113065. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2011.

- Asadova, P. S.; et al. (2003). "Genetic Structure of Iranian-Speaking Populations from Azerbaijan Inferred from the Frequencies of Immunological and Biochemical Gene Markers". Russian Journal of Genetics. 39 (11): 1334–1342. doi:10.1023/B:RUGE.0000004149.62114.92. S2CID 40679768.

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Valeev, Albert; Litvinov, Sergei; Valiev, Ruslan; Akhmetova, Vita; Balanovska, Elena; Balanovsky, Oleg; Turdikulova, Shahlo; Dalimova, Dilbar (21 April 2015). "The Genetic Legacy of the Expansion of Turkic-Speaking Nomads across Eurasia". PLOS Genetics. 11 (4): e1005068. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005068. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 4405460. PMID 25898006.

Our ADMIXTURE analysis (Fig 2) revealed that Turkic-speaking populations scattered across Eurasia tend to share most of their genetic ancestry with their current geographic non-Turkic neighbors. This is particularly obvious for Turkic peoples in Anatolia, Iran, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe, but more difficult to determine for northeastern Siberian Turkic speakers, Yakuts and Dolgans, for which non-Turkic reference populations are absent. We also found that a higher proportion of Asian genetic components distinguishes the Turkic speakers all over West Eurasia from their immediate non-Turkic neighbors. These results support the model that expansion of the Turkic language family outside its presumed East Eurasian core area occurred primarily through language replacement, perhaps by the elite dominance scenario, that is, intrusive Turkic nomads imposed their language on indigenous peoples due to advantages in military and/or social organization.

- Yepiskoposian, L.; et al. (2011). "The Location of Azaris on the Patrilineal Genetic Landscape of the Middle East (A Preliminary Report)". Iran and the Caucasus. 15 (1): 73–78. doi:10.1163/157338411X12870596615395.

- Berkman, Ceren Caner (September 2006). Comparative Analyses For The Central Asian Contribution To Anatolian Gene Pool With Reference To Balkans (PDF) (PhD). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Berkman CC, Dinc H, Sekeryapan C, Togan I (2008). "Alu insertion polymorphisms and an assessment of the genetic contribution of Central Asia to Anatolia with respect to the Balkans". Am J Phys Anthropol. 136 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20772. PMID 18161848.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nasidze, S; Stoneking, M. (2001). "Mitochondrial DNA variation and language replacements in the Caucasus". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 268 (1472): 1197–1206. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1610. PMC 1088727. PMID 11375109.

- Quintana-Murci, L.; et al. (2004). "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 827–845. doi:10.1086/383236. PMC 1181978. PMID 15077202.

- Zerjal, T.; et al. (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- Derenko, M.; Malyarchuk, B.; Bahmanimehr, A.; Denisova, G.; Perkova, M.; Farjadian, S.; Yepiskoposyan, L. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Iranians". PLOS ONE. 8 (11): e80673. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880673D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080673. PMC 3828245. PMID 24244704.

- Farjadian, S.; Ghaderi, A. (2007). "HLA class II similarities in Iranian Kurds and Azeris". International Journal of Immunogenetics. 34 (6): 457–63. doi:10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00723.x. PMID 18001303. S2CID 22709345.

- Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio; Palacio-Gruber, Jose; Muñiz, Ester; Rey, Diego; Nikbin, Behrouz; Nickman, Hosein; Campos, Cristina; Martín-Villa, José Manuel; Amirzargar, Ali (31 October 2017). "Origin of Azeris (Iran) according to HLA genes". International Journal of Modern Anthropology. African Journals Online (AJOL). 1 (10): 115. doi:10.4314/ijma.v1i10.5. ISSN 1737-8176.