Bethlehem

Bethlehem (/ˈbɛθlɪhɛm/; Arabic: بيت لحم, Bayt Laḥm, ⓘ; Hebrew: בֵּית לֶחֶם Bēṯ Leḥem) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Jerusalem. It is the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate, and has a population of approximately 25,000 people.[3][4] The city's economy is largely tourist-driven; international tourism peaks around and during Christmas, when Christians embark on a pilgrimage to the Church of the Nativity, revered as the location of the Nativity of Jesus.[5][6] At the northern entrance of the city is Rachel's Tomb, the burial place of biblical matriarch Rachel. Movement around the city is limited due to the Israeli West Bank barrier.

Bethlehem | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | بيت لحم |

| • Latin | Beit Laḥm (official) Bayt Laḥm (unofficial) |

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Hebrew | בֵּית לֶחֶם |

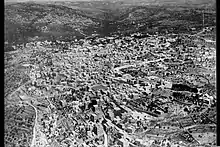

Skyline of Bethlehem near the Church of the Nativity (2009) | |

Municipal Seal (PNA) | |

Bethlehem Location of Bethlehem within the West Bank  Bethlehem Location of Bethlehem within the State of Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°42′11″N 35°11′44″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Bethlehem |

| Founded | 1400 BCE (est.) |

| Government | |

| • Type | Area A City (from 1995) |

| • Head of Municipality | Anton Salman[1] |

| Area | |

| • Municipality type A | 10,611 dunams (10.611 km2 or 4.097 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Municipality type A | 28,591 |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 97,559 |

| Demonym | Bethlehemi |

| Etymology | House of Meat (Arabic); House of Bread (Hebrew, Aramaic) |

| Website | www.bethlehem-city.org |

The earliest-known mention of Bethlehem is in the Amarna correspondence of ancient Egypt, dated to 1350–1330 BCE, when the town was inhabited by the Canaanites. In the Hebrew Bible, the period of the Israelites is described; it identifies Bethlehem as the birthplace of David as well as the city where he was anointed as the third monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel, and also states that it was built up as a fortified city by Rehoboam, the first monarch of the Kingdom of Judah.[7] In the New Testament, the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke identify the city as the birthplace of Jesus of Nazareth. Under the Roman Empire, the city of Bethlehem was destroyed by Hadrian, who was in the process of defeating Jews involved in the Bar Kokhba revolt. However, Bethlehem's rebuilding was later promoted by Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great; Constantine expanded on his mother's project by commissioning the Church of the Nativity in 327 CE. In 529, the Church of the Nativity was heavily damaged by Samaritans involved in the Samaritan revolts; following the victory of the Byzantine Empire, it was rebuilt a century later by Justinian I.

Amidst the Muslim conquest of the Levant, Bethlehem became part of Jund Filastin in 637. Muslims continued to rule the city until 1099, when it was conquered by the Crusaders, who replaced the local Christian clergy—composed of representatives from the Greek Orthodox Church—with representatives from the Catholic Church. In the mid-13th century, Bethlehem's walls were demolished by the Mamluk Sultanate. However, they were rebuilt by the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, following the Ottoman–Mamluk War.[8] At the end of World War I, the defeated Ottomans lost control of Bethlehem to the British Empire. It was governed under the British Mandate for Palestine until 1948, when it was captured by Jordan during the First Arab–Israeli War (see Jordanian annexation of the West Bank). In 1967, the city was captured by Israel during the Third Arab–Israeli War. Since the Oslo Accords, which comprise a series of agreements between Israel and the Palestinian National Authority, Bethlehem has been designated as part of Area A of the West Bank, nominally rendering it as being under full Palestinian control.[8]

While it was historically a city of Arab Christians, Bethlehem now has a majority of Arab Muslims; it is still home to a significant community of Palestinian Christians, however.[9][10] Presently, Bethlehem has become encircled by dozens of Israeli settlements, which effectively separate Palestinians in the city from being able to openly access their land and livelihoods, and has likewise triggered their steady exodus.[11]

Etymology

The current name for Bethlehem in local languages is ⓘ in Arabic (Arabic: بيت لحم), literally meaning "house of meat", and Bet Leḥem in Hebrew (Hebrew: בֵּית לֶחֶם), literally "house of bread" or "house of food."[12] The city was called in Ancient Greek: Βηθλεέμ Greek pronunciation: [bɛːtʰle.ém] and in Latin: Bethleem.[13]

The earliest mention of Bethlehem as a place appears in the Amarna correspondence (c. 1400 BCE), in which it is referred to as Bit-Laḫmi,[14] a name for which the origins remain unknown. One longstanding suggestion in scholarship is that it derives from the Mesopotamian or Canaanite fertility god Laḫmu and his consort sister Lahamu,[15] lahmo being the Chaldean word for "fertility".[13][16] Biblical scholar William F. Albright believed that this hypothesis, first put forth by Otto Schroeder, was "certainly accurate".[lower-alpha 1] Albright noted that the pronunciation of the name had remained essentially the same for 3,500 years, even if the perceived meaning had shifted over time: "'Temple of the God Lakhmu' in Canaanite, 'House of Bread' in Hebrew and Aramaic, 'House of Meat' in Arabic."[17] While Schroeder's theory is not widely accepted,[12] it continues to find favour in academic literature over the later literal translations.[18] Another suggestion is an association with the root l-h-m "to fight", but this is thought unlikely.[12]

History

Canaanite period

The earliest reference to Bethlehem appears in the Amarna correspondence (c. 1400 BCE). In one of his six letters to Pharaoh, Abdi-Heba, the Egyptian-appointed governor of Jerusalem, appeals for aid in retaking Bit-Laḫmi in the wake of disturbances by Apiru mercenaries:[14] "Now even a town near Jerusalem, Bit-Lahmi by name, a village which once belonged to the king, has fallen to the enemy... Let the king hear the words of your servant Abdi-Heba, and send archers to restore the imperial lands of the king!"

It is thought that the similarity of this name to its modern forms indicates that it was originally a settlement of Canaanites who shared a Semitic cultural and linguistic heritage with the later arrivals.[19] Laḫmu was the Akkadian god of fertility,[20] worshipped by the Canaanites as Leḥem. Some time in the third millennium BCE, Canaanites erected a temple on the hill now known as the Hill of the Nativity, probably dedicated to Laḫmu. The temple, and subsequently the town that formed around it, was then known as Beit Lahama, "House (Temple) of Lahmu". By 1200 BC, the area of Bethlehem, as well as much of the region, was conquered by the Philistines, which led the region to be known to the Greeks as "Philistia", later corrupted to "Palestine".[21]

A burial ground discovered in spring 2013, and surveyed in 2015 by a joint Italian–Palestinian team found that the necropolis covered 3 hectares (more than 7 acres) and originally contained more than 100 tombs in use between roughly 2200 BCE and 650 BCE. The archaeologists were able to identify at least 30 tombs.[22]

Israelite and Judean period

Archaeological confirmation of Bethlehem as a city in the Kingdom of Judah was uncovered in 2012 at the archaeological dig at the City of David in the form of a bulla (seal impression in dried clay) in ancient Hebrew script that reads "From the town of Bethlehem to the King." According to the excavators, it was used to seal the string closing a shipment of grain, wine, or other goods sent as a tax payment in the 8th or 7th century BCE.[23]

Biblical scholars believe Bethlehem, located in the "hill country" of Judea, may be the same as the Biblical Ephrath,[24] which means "fertile", as there is a reference to it in the Book of Micah as Bethlehem Ephratah.[25] The Hebrew Bible also calls it Beth-Lehem Judah,[26] and the New Testament describes it as the "City of David".[27] It is first mentioned in the Bible as the place where the matriarch Rachel died and was buried "by the wayside" (Genesis 48:7). Rachel's Tomb, the traditional grave site, stands at the entrance to Bethlehem. According to the Book of Ruth, the valley to the east is where Ruth of Moab gleaned the fields and returned to town with Naomi. In the Books of Samuel, Bethlehem is mentioned as the home of Jesse,[28] father of King David of Israel, and the site of David's anointment by the prophet Samuel.[29] It was from the well of Bethlehem that three of his warriors brought him water when he was hiding in the cave of Adullam.[30]

Writing in the 4th century, the Pilgrim of Bordeaux reported that the sepulchers of David, Ezekiel, Asaph, Job, Jesse, and Solomon were located near Bethlehem.[31] There has been no corroboration of this.

Classical period

.jpg.webp)

The Gospel of Matthew Matthew 1:18–2:23[35] and the Gospel of Luke Luke 2:1–39[36] represent Jesus as having been born in Bethlehem.[32][33][34] Modern scholars, however, regard the two accounts as contradictory[33][34] and the Gospel of Mark, the earliest gospel, mentions nothing about Jesus having been born in Bethlehem, saying only that he came from Nazareth.[34] Current scholars are divided on the actual birthplace of Jesus: some believe he was actually born in Nazareth,[37][38][39] while others still hold that he was born in Bethlehem.[40]

Nonetheless, the tradition that Jesus was born in Bethlehem was prominent in the early church.[32] In around 155, the apologist Justin Martyr recommended that those who doubted Jesus was really born in Bethlehem could go there and visit the very cave where he was supposed to have been born.[32] The same cave is also referenced by the apocryphal Gospel of James and the fourth-century church historian Eusebius.[32] After the Bar Kokhba revolt (c. 132–136 CE) was crushed, the Roman emperor Hadrian converted the Christian site above the Grotto into a shrine dedicated to the Greek god Adonis, to honour his favourite, the Greek youth Antinous.[41][42]

In around 395 CE, the Church Father Jerome wrote in a letter: "Bethlehem... belonging now to us... was overshadowed by a grove of Tammuz, that is to say, Adonis, and in the cave where once the infant Christ cried, the lover of Venus was lamented."[43] Many scholars have taken this letter as evidence that the cave of the nativity over which the Church of the Nativity was later built had at one point been a shrine to the ancient Near Eastern fertility god Tammuz.[43][44] Eusebius, however, mentions nothing about the cave having been associated with Tammuz[43] and there are no other Patristic sources that suggest Tammuz had a shrine in Bethlehem.[43] Peter Welten has argued that the cave was never dedicated to Tammuz[43] and that Jerome misinterpreted Christian mourning over the Massacre of the Innocents as a pagan ritual over Tammuz's death.[43] Joan E. Taylor has countered this contention by arguing that Jerome, as an educated man, could not have been so naïve as to mistake Christian mourning over the Massacre of the Innocents as a pagan ritual for Tammuz.[43]

In 326–328, the empress Helena, consort of the emperor Constantius Chlorus, and mother of the emperor Constantine the Great, made a pilgrimage to Syra-Palaestina, in the course of which she visited the ruins of Bethlehem.[8][32] The Church of the Nativity was built at her initiative over the cave where Jesus was purported to have been born.[32] During the Samaritan revolt of 529, Bethlehem was sacked and its walls and the Church of the Nativity destroyed; they were rebuilt on the orders of the Emperor Justinian I.[8][32] In 614, the Persian Sassanid Empire, supported by Jewish rebels, invaded Palestina Prima and captured Bethlehem.[45] A story recounted in later sources holds that they refrained from destroying the church on seeing the magi depicted in Persian clothing in a mosaic.[46][8]

Middle Ages

_-_Geographicus_-_Bethlehem-bruijn-1698.jpg.webp)

In 637, shortly after Jerusalem was captured by the Muslim armies, 'Umar ibn al-Khattāb, the second Caliph, promised that the Church of the Nativity would be preserved for Christian use.[8] A mosque dedicated to Umar was built upon the place in the city where he prayed, next to the church.[47] Bethlehem then passed through the control of the Islamic caliphates of the Umayyads in the 8th century, then the Abbasids in the 9th century. A Persian geographer recorded in the mid-9th century that a well preserved and much venerated church existed in the town. In 985, the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi visited Bethlehem, and referred to its church as the "Basilica of Constantine, the equal of which does not exist anywhere in the country-round."[48] In 1009, during the reign of the sixth Fatimid Caliph, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, the Church of the Nativity was ordered to be demolished, but was spared by local Muslims, because they had been permitted to worship in the structure's southern transept.[49]

In 1099, Bethlehem was captured by the Crusaders, who fortified it and built a new monastery and cloister on the north side of the Church of the Nativity. The Greek Orthodox clergy were removed from their sees and replaced with Latin clerics. Up until that point the official Christian presence in the region was Greek Orthodox. On Christmas Day 1100, Baldwin I, first king of the Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem, was crowned in Bethlehem, and that year a Latin episcopate was also established in the town.[8]

In 1187, Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria who led the Muslim Ayyubids, captured Bethlehem from the Crusaders. The Latin clerics were forced to leave, allowing the Greek Orthodox clergy to return. Saladin agreed to the return of two Latin priests and two deacons in 1192. However, Bethlehem suffered from the loss of the pilgrim trade, as there was a sharp decrease of European pilgrims.[8] William IV, Count of Nevers had promised the Christian bishops of Bethlehem that if Bethlehem should fall under Muslim control, he would welcome them in the small town of Clamecy in present-day Burgundy, France. As a result, the Bishop of Bethlehem duly took up residence in the hospital of Panthenor, Clamecy, in 1223. Clamecy remained the continuous 'in partibus infidelium' seat of the Bishopric of Bethlehem for almost 600 years, until the French Revolution in 1789.[50]

Bethlehem, along with Jerusalem, Nazareth, and Sidon, was briefly ceded to the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem by a treaty between Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and Ayyubid Sultan al-Kamil in 1229, in return for a ten-year truce between the Ayyubids and the Crusaders. The treaty expired in 1239, and Bethlehem was recaptured by the Muslims in 1244.[51] In 1250, with the coming to power of the Mamluks under Rukn al-Din Baibars, tolerance of Christianity declined. Members of the clergy left the city, and in 1263 the town walls were demolished. The Latin clergy returned to Bethlehem the following century, establishing themselves in the monastery adjoining the Basilica of the Nativity. The Greek Orthodox were given control of the basilica and shared control of the Milk Grotto with the Latins and the Armenians.[8]

Ottoman era

From 1517, during the years of Ottoman control, custody of the Basilica was bitterly disputed between the Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches.[8] By the end of the 16th century, Bethlehem had become one of the largest villages in the District of Jerusalem, and was subdivided into seven quarters.[52] The Basbus family served as the heads of Bethlehem among other leaders during this period.[53] The Ottoman tax record and census from 1596 indicates that Bethlehem had a population of 1,435, making it the 13th largest village in Palestine at the time. Its total revenue amounted to 30,000 akce.[54]

Bethlehem paid taxes on wheat, barley and grapes. The Muslims and Christians were organized into separate communities, each having its own leader. Five leaders represented the village in the mid-16th century, three of whom were Muslims. Ottoman tax records suggest that the Christian population was slightly more prosperous or grew more grain than grapes (the former being a more valuable commodity).[55]

From 1831 to 1841, Palestine was under the rule of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty of Egypt. During this period, the town suffered an earthquake as well as the destruction of the Muslim quarter in 1834 by Egyptian troops, apparently as a reprisal for the murder of a favored loyalist of Ibrahim Pasha.[56] In 1841, Bethlehem came under Ottoman rule once again and remained so until the end of World War I. Under the Ottomans, Bethlehem's inhabitants faced unemployment, compulsory military service, and heavy taxes, resulting in mass emigration, particularly to South America.[8] An American missionary in the 1850s reported a population of under 4,000, nearly all of whom belonged to the Greek Church. He also noted that a lack of water limited the town's growth.[57]

Socin found from an official Ottoman village list from about 1870 that Bethlehem had a population of 179 Muslims in 59 houses, 979 "Latins" in 256 houses, 824 "Greeks" in 213 houses, and 41 Armenians in 11 houses, a total of 539 houses. The population count only included men.[58] Hartmann found that Bethlehem had 520 houses.[59]

Modern era

Bethlehem was administered by the British Mandate from 1920 to 1948.[60] In the United Nations General Assembly's 1947 resolution to partition Palestine, Bethlehem was included in the international enclave of Jerusalem to be administered by the United Nations.[61] Jordan captured the city during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[62] Many refugees from areas captured by Israeli forces in 1947–48 fled to the Bethlehem area, primarily settling in what became the official refugee camps of 'Azza (Beit Jibrin) and 'Aida in the north and Dheisheh in the south.[63] The influx of refugees significantly transformed Bethlehem's Christian majority into a Muslim one.[64]

Jordan retained control of the city until the Six-Day War in 1967, when Bethlehem was captured by Israel, along with the rest of the West Bank. Following the Six-Day War, Israel took control of the city.

During the early months of First Intifada, on 5 May 1989, Milad Anton Shahin, aged 12, was shot dead by Israeli soldiers. Replying to a Member of Knesset in August 1990 Defence Minister Yitzak Rabin stated that a group of reservists in an observation post had come under attack by stone throwers. The commander of the post, a senior non-commissioned officer, fired two plastic bullets in deviation of operational rules. No evidence was found that this caused the boy's death. The officer was found guilty of illegal use of a weapon and sentenced to 5 months imprisonment, two of them actually in prison doing public service. He was also demoted.[65]

On December 21, 1995, Israeli troops withdrew from Bethlehem,[66] and three days later the city came under the administration and military control of the Palestinian National Authority in accordance with the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.[67] During the Second Palestinian Intifada in 2000–2005, Bethlehem's infrastructure and tourism industry were damaged.[68][69] In 2002, it was a primary combat zone in Operation Defensive Shield, a major military counteroffensive by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).[70] The IDF besieged the Church of the Nativity, where dozens of Palestinian militants had sought refuge. The siege lasted 39 days. Several militants were killed. It ended with an agreement to exile 13 of the militants to foreign countries.[71]

Today, the city is surrounded by two bypass roads for Israeli settlers, leaving the inhabitants squeezed between thirty-seven Jewish enclaves, where a quarter of all West Bank settlers, roughly 170,000, live; the gap between the two roads is closed by the 8-metre high Israeli West Bank barrier, which cuts Bethlehem off from its sister city Jerusalem.[72]

Christian families that have lived in Bethlehem for hundreds of years are being forced to leave as land in Bethlehem is seized, and homes bulldozed, for construction of thousands of new Israeli homes.[11] Land seizures for Israeli settlements have also prevented construction of a new hospital for the inhabitants of Bethlehem, as well as the barrier separating dozens of Palestinian families from their farmland and Christian communities from their places of worship.[11]

Geography

Bethlehem is located at an elevation of about 775 meters (2,543 ft) above sea level, 30 meters (98 ft) higher than nearby Jerusalem.[73] Bethlehem is situated on the Judean Mountains.

The city is located 73 kilometers (45 mi) northeast of Gaza City and the Mediterranean Sea, 75 kilometers (47 mi) west of Amman, Jordan, 59 kilometers (37 mi) southeast of Tel Aviv, Israel and 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) south of Jerusalem.[74] Nearby cities and towns include Beit Safafa and Jerusalem to the north, Beit Jala to the northwest, Husan to the west, al-Khadr and Artas to the southwest, and Beit Sahour to the east. Beit Jala and the latter form an agglomeration with Bethlehem. The Aida and Azza refugee camps are located within the city limits.[75]

In the center of Bethlehem is its old city. The old city consists of eight quarters, laid out in a mosaic style, forming the area around the Manger Square. The quarters include the Christian an-Najajreh, al-Farahiyeh, al-Anatreh, al-Tarajmeh, al-Qawawsa and Hreizat quarters and al-Fawaghreh—the only Muslim quarter.[76] Most of the Christian quarters are named after the Arab Ghassanid clans that settled there.[77] Al-Qawawsa Quarter was formed by Arab Christian emigrants from the nearby town of Tuqu' in the 18th century.[78] There is also a Syriac quarter outside of the old city,[76] whose inhabitants originate from Midyat and Ma'asarte in Turkey.[79] The total population of the old city is about 5,000.[76]

Climate

Bethlehem has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa), with hot and dry summers and mild, wetter winters. Winter temperatures (mid-December to mid-March) can be cool and rainy. January is the coldest month, with temperatures ranging from 1 to 13 degree Celsius (33–55 °F). From May through September, the weather is warm and sunny. August is the hottest month, with a high of 30 degrees Celsius (86 °F). Bethlehem receives an average of 700 millimeters (28 in) of rainfall annually, 70% between November and January.[80]

Bethlehem's average annual relative humidity is 60% and reaches its highest rates between January and February. Humidity levels are at their lowest in May. Night dew may occur in up to 180 days per year. The city is influenced by the Mediterranean Sea breeze that occurs around mid-day. However, Bethlehem is affected also by annual waves of hot, dry, sandy and dust Khamaseen winds from the Arabian Desert, during April, May and mid-June.[80]

| Climate data for Bethlehem | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12 (54) |

13 (55) |

16 (61) |

22 (72) |

26 (79) |

28 (82) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

20 (68) |

14 (57) |

22 (72) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5 (41) |

5 (41) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

14 (57) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

19 (66) |

17 (63) |

15 (59) |

11 (52) |

7 (45) |

12 (54) |

| Average rainy days | 12 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 59 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Source: myweather2.com[81] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Population

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1867 | 3,000–4,000[82] |

| 1945 | 8,820[83][84] |

| 1961 | 22,453[85] |

| 1983 | 16,300[86] |

| 1997 | 21,930[87] |

| 2007 | 25,266[87] |

According to Ottoman tax records, Christians made up roughly 60% of the population in the early 16th century, while the Christian and Muslim population became equal by the mid-16th century. However, there were no Muslim inhabitants counted by the end of the century, with a recorded population of 287 adult male tax-payers. Christians, like all non-Muslims throughout the Ottoman Empire, were required to pay the jizya tax.[52] In 1867, an American visitor describes the town as having a population of 3,000 to 4,000; of whom about 100 were Protestants, 300 were Muslims and "the remainder belonging to the Latin and Greek Churches with a few Armenians."[82] Another report from the same year puts the Christian population at 3,000, with an additional 50 Muslims.[88] An 1885 source put the population at approximately 6,000 of "principally Christians, Latins and Greeks" with no Jewish inhabitants.[89]

The census of 1922 lists Bethlehem as having 6,658 residents (5,838 Christians, 818 Muslims, and two Jews),[90] increasing in 1931 to 6,804 (5,588 Christians, 1,219 Muslims, five with no religion, and two Jews) with 506 in the suburbs (251 Muslims, 216 Christians, and 39 Jews).[91]

In 1948, the religious makeup of the city was 85% Christian, mostly of the Greek Orthodox and Roman Catholic denominations, and 13% Muslim.[92] In the 1967 census taken by Israel authorities, the town of Bethlehem proper numbered 14,439 inhabitants, its 7,790 Muslim inhabitants represented 53.9% of the population, while the Christians of various denominations numbered 6,231 or 46.1%.[93]

In the PCBS's 1997 census, the city had a population of 21,670, including a total of 6,570 refugees, accounting for 30.3% of the city's population.[87][94] In 1997, the age distribution of Bethlehem's inhabitants was 27.4% under the age of 10, 20% from 10 to 19, 17.3% from 20 to 29, 17.7% from 30 to 44, 12.1% from 45 to 64 and 5.3% above the age of 65. There were 11,079 males and 10,594 females.[87] In the 2007 PCBS census, Bethlehem had a population of 25,266, of which 12,753 were males and 12,513 were females. There were 6,709 housing units, of which 5,211 were households. The average household consisted of 4.8 family members.[95]

Christian population

After the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s, the local Christians were Arabized even though large numbers were ethnically Arabs of the Ghassanid clans.[96] Bethlehem's two largest Arab Christian clans trace their ancestry to the Ghassanids, including al-Farahiyyah and an-Najajreh.[96] The former have descended from the Ghassanids who migrated from Yemen and from the Wadi Musa area in present-day Jordan and an-Najajreh descend from Najran.[96] Another Bethlehem clan, al-Anatreh, also trace their ancestry to the Ghassanids.[96]

The percentage of Christians in the town has been in a steady decline since the mid-twentieth century.[92][97][98][99] In 1947, Christians made up 85% of the population, but by 1998, the figure had declined to 40%.[92][97] In 2005, the mayor of Bethlehem, Victor Batarseh, explained that "due to the stress, either physical or psychological, and the bad economic situation, many people are emigrating, either Christians or Muslims, but it is more apparent among Christians, because they already are a minority."[100] The Palestinian Authority is officially committed to equality for Christians, although there have been incidents of violence against them by the Preventive Security Service and militant factions.[101][102] In 2006, the Palestinian Centre for Research and Cultural Dialogue conducted a poll among the city's Christians according to which 90% said they had had Muslim friends, 73.3% agreed that the PNA treated Christian heritage in the city with respect and 78% attributed the exodus of Christians to the Israeli blockade.[103] The only mosque in the Old City is the Mosque of Omar, located in the Manger Square.[47] By 2016, the Christian population of Bethlehem had declined to only 16%.[98]

A study by Pew Research Center concluded that the decline in the Arab Christian population of the area was partially a result of a lower birth rate among Christians than among Muslims,[98][104] but also partially due to the fact that Christians were more likely to emigrate from the region than any other religious group.[98][104] Amon Ramnon, a researcher at the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research, stated that the reason why more Christians were emigrating than Muslims is because it is easier for Arab Christians to integrate into western communities than for Arab Muslims, since many of them attend church-affiliated schools, where they are taught European languages.[98] A higher percentage of Christians in the region are urban-dwellers, which also makes it easier for them to emigrate and assimilate into western populations.[98] A statistical analysis of the Christian exodus cited lack of economic and educational opportunity, especially due to the Christians' middle-class status and higher education.[105] Since the Second Intifada, 10% of the Christian population have left the city.[100] However, it is likely that there are many other factors, most of which are shared with the Palestinian population as a whole.[106]

Economy

Shopping is a major attraction, especially during the Christmas season. The city's main streets and old markets are lined with shops selling Palestinian handicrafts, Middle Eastern spices, jewelry and oriental sweets such as baklawa.[107] Olive wood carvings [108] are the item most purchased by tourists visiting Bethlehem.[109] Religious handicrafts include ornaments handmade from mother-of-pearl, as well as olive wood statues, boxes, and crosses.[108] Other industries include stone and marble-cutting, textiles, furniture and furnishings.[110] Bethlehem factories also produce paints, plastics, synthetic rubber, pharmaceuticals, construction materials and food products, mainly pasta and confectionery.[110]

Cremisan Wine, founded in 1885, is a winery run by monks in the Monastery of Cremisan. The grapes are grown mainly in the al-Khader district. In 2007, the monastery's wine production was around 700,000 liters per year.[111]

In 2008, Bethlehem hosted the largest economic conference to date in the Palestinian territories. It was initiated by Palestinian Prime Minister and former Finance Minister Salam Fayyad to convince more than a thousand businessmen, bankers and government officials from throughout the Middle East to invest in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. A total of 1.4 billion US dollars was secured for business investments in the Palestinian territories.[112]

Tourism

Tourism is Bethlehem's main industry.[99][68] Unlike other Palestinian localities prior to 2000, the majority of the employed residents did not have jobs in Israel.[68] More than 20% of the working population is employed in the industry.[113] Tourism accounts for approximately 65% of the city's economy and 11% of the Palestinian National Authority.[114] The city has more than two million visitors every year.[113] Tourism in Bethlehem ground to a halt for over a decade after the Second Intifada,[99] but gradually began to pick back up in the early 2010s.[99]

The Church of the Nativity is one of Bethlehem's major tourist attractions and a magnet for Christian pilgrims. It stands in the center of the city — a part of the Manger Square — over a grotto or cave called the Holy Crypt, where Jesus is believed to have been born. Nearby is the Milk Grotto where the Holy Family took refuge on their Flight to Egypt and next door is the cave where St. Jerome spent thirty years creating the Vulgate, the dominant Latin version of the Bible until the Reformation.[8]

There are over thirty hotels in Bethlehem.[115] Jacir Palace, built in 1910 near the church, is one of Bethlehem's most successful hotels and its oldest. It was closed down in 2000 due to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but reopened in 2005 as the Jacir Palace InterContinental at Bethlehem.[116]

Religious significance and commemoration

Birthplace of Jesus

In the New Testament, the Gospel of Luke says that Jesus' parents traveled from Nazareth to Bethlehem, where Jesus was born.[27] The Gospel of Matthew mentions Bethlehem as the place of birth,[117] and adds that King Herod was told that a 'King of the Jews' had been born in the town, prompting Herod to order the killing of all the boys who were two years old or under in the town and surrounding area. Joseph, warned of Herod's impending action by an angel of the Lord, decided to flee to Egypt with his family and then later settled in Nazareth after Herod's death.

Early Christian traditions describe Jesus as being born in Bethlehem: in one account, a verse in the Book of Micah is interpreted as a prophecy that the Messiah would be born there.[118] The second century Christian apologist Justin Martyr stated in his Dialogue with Trypho (written c. 155–161) that the Holy Family had taken refuge in a cave outside of the town and then placed Jesus in a manger.[119] Origen of Alexandria, writing around the year 247, referred to a cave in the town of Bethlehem which local people believed was the birthplace of Jesus.[120] This cave was possibly one which had previously been a site of the cult of Tammuz.[121][122][123][124][125] The Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of John do not include a nativity narrative, but refer to him only as being from Nazareth.[126] In a 2005 article in Archaeology magazine, archaeologist Aviram Oshri points to an absence of evidence for the settlement of Bethlehem near Jerusalem at the time when Jesus was born, and postulates that Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Galilee.[127] In a 2011 article in Biblical Archaeology Review magazine, Jerome Murphy-O'Connor argues for the traditional position that Jesus was born in Bethlehem near Jerusalem.[128]

Christmas celebrations

Christmas rites are held in Bethlehem on three different dates: December 25 is the traditional date by the Roman Catholic and Protestant denominations, but Greek, Coptic and Syrian Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas on January 6 and Armenian Orthodox Christians on January 19. Most Christmas processions pass through Manger Square, the plaza outside the Basilica of the Nativity. Roman Catholic services take place in St. Catherine's Church and Protestants often hold services at Shepherds' Fields.[129]

Other religious festivals

Bethlehem celebrates festivals related to saints and prophets associated with Palestinian folklore. One such festival is the annual Feast of Saint George (al-Khadr) on May 5–6. During the celebrations, Greek Orthodox Christians from the city march in procession to the nearby town of al-Khader to baptize newborns in the waters around the Monastery of St. George and sacrifice a sheep in ritual.[130] The Feast of St. Elijah is commemorated by a procession to Mar Elias, a Greek Orthodox monastery north of Bethlehem.

Culture

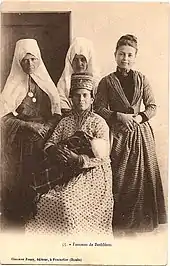

Embroidery

The women embroiderers of Bethlehem were known for their bridalwear.[131] Bethlehem embroidery was renowned for its "strong overall effect of colors and metallic brilliance."[132] Less formal dresses were made of indigo fabric with a sleeveless coat (bisht) from locally woven wool worn over top. Dresses for special occasions were made of striped silk with winged sleeves with a short taqsireh jacket known as the Bethlehem jacket. The taqsireh was made of velvet or broadcloth, usually with heavy embroidery.[131]

Bethlehem work was unique in its use of couched gold or silver cord, or silk cord onto the silk, wool, felt or velvet used for the garment, to create stylized floral patterns with free or rounded lines. This technique was used for "royal" wedding dresses (thob malak), taqsirehs and the shatwehs worn by married women. It has been traced by some to Byzantium, and by others to the formal costumes of the Ottoman Empire's elite. As a Christian village, local women were also exposed to the detailing on church vestments with their heavy embroidery and silver brocade.[131]

Mother-of-pearl carving

The art of mother-of-pearl carving is said to have been a Bethlehem tradition since the 15th century when it was introduced by Franciscan friars from Italy.[133] A constant stream of pilgrims generated a demand for these items, which also provided jobs for women.[134] The industry was noted by Richard Pococke, who visited Bethlehem in 1727.[135]

Cultural centers and museums

Bethlehem is home to the Palestinian Heritage Center, established in 1991. The center aims to preserve and promote Palestinian embroidery, art and folklore.[136] The International Center of Bethlehem is another cultural center that concentrates primarily on the culture of Bethlehem. It provides language and guide training, woman's studies and arts and crafts displays, and training.[6]

The Bethlehem branch of the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music has about 500 students. Its primary goals are to teach children music, train teachers for other schools, sponsor music research, and the study of Palestinian folklore music.[137]

Bethlehem has four museums: The Crib of the Nativity Theatre and Museum offers visitors 31 three-dimensional models depicting the significant stages of the life of Jesus. Its theater presents a 20-minute animated show. The Badd Giacaman Museum, located in the Old City of Bethlehem, dates back to the 18th century and is primarily dedicated to the history and process of olive oil production.[6] Baituna al-Talhami Museum, established in 1972, contains displays of Bethlehem culture.[6] The International Museum of Nativity was built by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to exhibit "high artistic quality in an evocative atmosphere".[6]

Local government

Bethlehem is the muhfaza (seat) or district capital of the Bethlehem Governorate.

Bethlehem held its first municipal elections in 1876, after the mukhtars ("heads") of the quarters of Bethlehem's Old City (excluding the Syriac Quarter) made the decision to elect a local council of seven members to represent each clan in the town. A Basic Law was established so that if the victor for mayor was a Catholic, his deputy should be of the Greek Orthodox community.[138]

Throughout, Bethlehem's rule by the British and Jordan, the Syriac Quarter was allowed to participate in the election, as were the Ta'amrah Bedouins and Palestinian refugees, hence ratifying the number of municipal members in the council to 11. In 1976, an amendment was passed to allow women to vote and become council members and later the voting age was increased from 21 to 25.[138]

There are several branches of political parties on the council, including Communist, Islamist, and secular. The leftist factions of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Palestinian People's Party (PPP) usually dominate the reserved seats. Hamas gained the majority of the open seats in the 2005 Palestinian municipal elections.[139]

Mayors

In the October 2012 municipal elections, Fatah member Vera Baboun won, becoming the first female mayor of Bethlehem.[140]

|

|

Education

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), in 1997, approximately 84% of Bethlehem's population over the age of 10 was literate. Of the city's population, 10,414 were enrolled in schools (4,015 in primary school, 3,578 in secondary and 2,821 in high school). About 14.1% of high school students received diplomas.[143] There were 135 schools in the Bethlehem Governorate in 2006; 100 run the Education Ministry of the Palestinian National Authority, seven by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) and 28 were private.[144]

Bethlehem is home to Bethlehem University, a Catholic Christian co-educational institution of higher learning founded in 1973 in the Lasallian tradition, open to students of all faiths. Bethlehem University is the first university established in the West Bank, and can trace its roots to 1893 when the De La Salle Christian Brothers opened schools throughout Palestine and Egypt.[145]

Transportation

Bethlehem has three bus stations owned by private companies which offer service to Jerusalem, Beit Jala, Beit Sahour, Hebron, Nahalin, Battir, al-Khader, al-Ubeidiya and Beit Fajjar. There are two taxi stations that make trips to Beit Sahour, Beit Jala, Jerusalem, Tuqu' and Herodium. There are also two car rental departments: Murad and 'Orabi. Buses and taxis with West Bank licenses are not allowed to enter Israel, including Jerusalem, without a permit.[146]

The Israeli construction of the West Bank barrier has affected Bethlehem politically, socially, and economically. The barrier is located along the northern side of the town's built-up area, within distance of houses in the Aida refugee camp on one side, and the Jerusalem municipality on the other.[68] Most entrances and exits from the Bethlehem agglomeration to the rest of the West Bank are currently subjected to Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks. The level of access varies based on Israeli security directives. Travel for Bethlehem's Palestinian residents from the West Bank into Jerusalem is regulated by a permit-system.[147] Palestinians require a permit to enter the Jewish holy site of Rachel's Tomb. Israeli citizens are barred from entering Bethlehem and the nearby biblical Solomon's Pools.[68]

Twin towns – sister cities

Bethlehem is twinned with:[148][149][150]

Abu Dhabi, U.A.E.

Abu Dhabi, U.A.E. Assisi, Italy

Assisi, Italy Athens, Greece

Athens, Greece Barranquilla, Colombia

Barranquilla, Colombia Brescia, Italy

Brescia, Italy Burlington, USA

Burlington, USA Capri, Italy

Capri, Italy Catanzaro, Italy

Catanzaro, Italy Chartres, France

Chartres, France Chivasso, Italy

Chivasso, Italy Civitavecchia, Italy

Civitavecchia, Italy Cologne, Germany

Cologne, Germany Concepción, Chile

Concepción, Chile Cori, Italy

Cori, Italy Creil, France

Creil, France Cusco, Peru

Cusco, Peru Częstochowa, Poland

Częstochowa, Poland Dakhla, Western Sahara

Dakhla, Western Sahara Este, Italy

Este, Italy Faggiano, Italy

Faggiano, Italy Florence, Italy

Florence, Italy Gallipoli, Italy

Gallipoli, Italy Għajnsielem, Malta

Għajnsielem, Malta Glasgow, Scotland, U.K.

Glasgow, Scotland, U.K. Greccio, Italy

Greccio, Italy Grenoble, France

Grenoble, France Lourdes, France

Lourdes, France Monterrey, Mexico

Monterrey, Mexico Montevarchi, Italy

Montevarchi, Italy Montpellier, France

Montpellier, France Natal, Brazil

Natal, Brazil Pratovecchio Stia, Italy

Pratovecchio Stia, Italy Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Sarpsborg, Norway

Sarpsborg, Norway Steyr, Austria

Steyr, Austria Villa Alemana, Chile

Villa Alemana, Chile Zaragoza, Spain

Zaragoza, Spain

Notes

- The explanation of Bet-leḥem as the "House of (the god) Lahmu" is due to Otto Schroeder, OLZ, 1915, pp. 294 f. This explanation is certainly correct [...][17]

References

- "Members of the Municipal Council". Bethlehem municipality. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- "Main Indicators by Type of Locality - Population, Housing and Establishments Census 2017" (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- Amara, 1999, p. 18 Archived May 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- Brynen, 2000, p. 202 Archived May 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- Kaufman, David; Katz, Marisa S. (April 16, 2006). "In the West Bank, Politics and Tourism Remain Bound Together Inextricably – New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Places to Visit In & Around Bethlehem". Bethlehem Hotel. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- 2 Chronicles 11:5–6 (Note: Though v. 6 is frequently translated to say simply that Rehoboam built the city, the Hebrew phrase in v. 5, just prior, וַיִּ֧בֶן עָרִ֛ים לְמָצ֖וֹר wayyiḇen ‘ārîm lemāṣôr means "(and) he built cities into fortresses". Verse 5 is cited by at least one prominent Hebrew lexicon in illustration of this fact. See Koehler, L., Baumgartner, W., Richardson, M. E. J., & Stamm, J. J., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (electronic edition; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), entry for the pertinent root בנה bnh, p. 139. Def. 3 reads as follows: "—3. with לְ to develop buildings: עָרִים לְמָצוֹר cities into fortresses 2C[hronicles] 11:5".)

- "History and Mithology of Bethlehem". Bethlehem Municipality. Archived from the original on January 13, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- Kamin, Debra. "Are Bethlehem's Christians losing grip on their city?". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- Klein, Aaron; Daily, World Net (December 27, 2005). "'Muslims persecuting Bethlehem's Christians'". Ynetnews. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- Philp, Catherine (December 24, 2013). "Settlements choke peace in the little town of Bethlehem". The Times. pp. 28–29.

- Corpus inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: a multi-lingual corpus of the inscriptions from Alexander to Muhammad. Vol. IV: Iudaea / Idumaea. Eran Lupu, Marfa Heimbach, Naomi Schneider, Hannah Cotton. Berlin: de Gruyter. 2010. p. 635. ISBN 978-3-11-022219-7. OCLC 663773367.

The name Bethlehem (Hebr. Bet Leḥem; LXX Βηθλέεμ; Βαιθλέεμ; Aramaic Bêt leḥem) combines the Hebrew words bayit "house" and leḥem "bread" and thus means "house of bread/food." Some claim that it is connected with the verb root lḥm "to fight," whence it would mean "house of war/fighting." That seems less likely. It has also been suggested that there is a connection with the name of the Mesopotamian goddess, Laḫmu, the mother of Anšar (sky) and Kišar (earth) in the Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, but this is generally rejected.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Losch, Richard R. (2005). The uttermost part of the earth: a guide to places in the Bible (Illustrated ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8028-2805-7. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "Oxford Archeological Guides: The Holy Land", Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, pp. 198–199, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-19-288013-0

- "Bethledhem". Etymology Online.

- Wright, G. R. H. (January 1, 1986). "The Mother-Maid at Bethlehem". Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 98 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1515/zatw.1986.98.1.56. ISSN 1613-0103. S2CID 170130221.

The form of the name Bethlehem certainly connotes that the latter element is not a common noun but a proper noun, the name of a god who has his temple (house) there - cf. Beth Shemesh etc. Accordingly the literal version, House of Bread, has been put down as folk etymology. Divine names can be found to fit the bill; e.g., Lahmu and Lahamu mentioned in the Babylonian creation epic as offspring of Apsu and Tiamat (v. Staples, AJSL 52, 149—50). Since, however, the name as generally understood is so apt for an agricultural fertility cult centre, it is possible that the question has not been fully probed (cf. Interpreters' Bible Vol. 2, 853).

- Albright 1936.

- Wasilewski, E. (2016). "Pastoral exhortations – a key to preliminary homiletic research". The Biblical and Liturgical Movement. 69 (2): 125–142. doi:10.21906/rbl.187.

- "International Dictionary of Historic Places: Vol 4, Middle East and Africa", Trudy Ring, K.A Berney, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger, p. 133, Taylor & Francis, 1996, ISBN 978-1-884964-03-9.

- Losch, Richard R. (2005). The Uttermost Part of the Earth: A Guide to Places in the Bible. Wm. A. Eerdmans. p. 51.

- Losch, Richard R. (2005). The uttermost part of the earth: a guide to places in the Bible (Illustrated ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8028-2805-7. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "Ancient Burial Ground with 100 Tombs Found Near Biblical Bethlehem". LiveScience.com. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- "Israel Antiquities Authority". antiquities.org.il. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- Gen. 35:16, Gen. 48:7, Ruth 4:11

- Micah 5:2

- 1 Sam 17:12

- Luke 2:4

- 1Sam 16:1

- 1Sam 16:4–13

- 2Sam 23:13–17

- "The Bordeaux Pilgrim @". Centuryone.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Brownrigg, Ronald (2002) [1971]. "Jesus: The Birth Stories". Who's Who in the New Testament. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-0-203-01712-8. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Sanders, E. P. (1993). The Historical Figure of Jesus. London, England, New York City, New York, Ringwood, Australia, Toronto, Ontario, and Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-0-14-014499-4.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. New York City, New York and London, England: T & T Clark. pp. 145–158. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- 1:18–2:23

- 2:1–39

- Brown, Raymond Edward (1999). The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-49447-2.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The roots of the problem and the person. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-26425-9.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512474-3.

- Murphy O'Connor, Jerome (August 24, 2015). "Bethlehem…Of Course". Biblical Archaeology Review. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- Giuseppe Ricciotti, Vita di Gesù Cristo, Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana (1948) p. 276 n.

- Maier, Paul L., "The First Christmas: The True and Unfamiliar Story." 2001

- Taylor, Joan E. (1993). Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-19-814785-5. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Marcello Craveri, The Life of Jesus, Grove Press (1967) pp. 35–36

- Klein 2018, p. 234.

- Russell 1991, pp. 523–528.

- "Mosque of Omar, Bethlehem". Atlas Travel and Tourist Agency. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- le Strange, 1890, pp. 298–300.

- "Church of the Nativity – Bethlehem". Bethlehem, West Bank, Israel: Sacred-destinations.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- de Sivry, L: "Dictionnaire de Géographie Ecclésiastique", p. 375., 1852 ed, from ecclesiastical record of letters between the Bishops of Bethlehem 'in partibus' to the bishops of Auxerre.

- Paul Reed, 2000, p. 206.

- Singer, 1994, p. 80 Archived December 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Singer, 1994, p. 33 Archived December 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Petersen, 2005, p. 141.

- Singer, 1994, p. 84 Archived December 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Thomson, 1860, p. 647.

- W. M. Thomson, p. 647.

- Socin, 1879, p. 146

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 124

- Bethlehem. Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "IMEU: Maps: 2.7 – Jerusalem and the Corpus Separatum proposed in 1947". Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- A Jerusalem Timeline, 3,000 Years of The City's History Archived January 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine (2001–02) National Public Radio and BBC News.

- "About Bethlehem". Archived from the original on November 13, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2016. The Centre for Cultural Heritage Preservation via Bethlehem.ps.

- Population in the Bethlehem District Bethlehem.ps.

- Talmor, Ronny (translated by Ralph Mandel) (1990) The Use of Firearms - By the Security Forces in the Occupied Territories. B'Tselem. download Archived September 14, 2014, at the Wayback Machine p. 75 MK Yair Tsaban to defence ministers Yitzhak Rabin & Yitzhak Shamir p.81 Rabin's reply

- "Palestine Facts Timeline: 1994–1995". Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

- Kessel, Jerrold (December 24, 1995). "Muslims, Christians celebrate in Bethlehem". CNN. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) & Office of the Special Coordinator for the Peace Process in the Middle East (December 2004). "Costs of Conflict: The Changing Face of Bethlehem" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 29, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- Patience, Martin (December 22, 2007). "Better times return to Bethlehem". BBC News. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Vatican outrage over church siege". BBC News. April 8, 2002. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

- "Chronology of the Siege". Frontline. PBS. Archived from the original on December 27, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2013.

- Nicholas Blincoe, 'Phantom Bids,' Archived January 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine London Review of Books, August 14, 2014

- "Tourism In Bethlehem Governorate". Palestinian National Information Center. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007.

- Distance from Bethlehem to Tel Aviv Archived November 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Distance from Bethlehem to Gaza Archived November 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Time and Date AS / Steffen Thorsen.

- Detailed map of the West Bank.

- Bethlehem's Quarters Centre for Cultural Heritage Preservation

- Clans −2 Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Mediterranean Voices: Oral History and Cultural Practice in Mediterranean Cities

- Tqoa' area Zeiter, Leila. Centre for Preservation of Culture and History.

- Short Overview of the Bato Family BatoFamily.com

- "Bethlehem City: Climate". Bethlehem Municipality. Archived from the original on November 28, 2007.

- "January Climate History for Bethlehem | Local | Israel". Myweather2.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- Ellen Clare Miller, 'Eastern Sketches – notes of scenery, schools and tent life in Syria and Palestine'. Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Company. 1871. p. 148.

- Hadawi, Sami. "Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine". Palestine Liberation Organization – Research Center. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 7 Archived January 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Census by Israel Central Bureau of Statistics

- Palestinian Population by Locality, Sex and Age Groups in Years: Bethlehem Governorate (1997) Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- William Wyndham Malet (1868). The olive leaf: a pilgrimage to Rome, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, in 1867, for the reunion of the faithful. T. Bosworth. p. 116. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- '"Bethlehem". The Jewish Intelligence: 5. January 1885. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2014.

- Palestine Census ( 1922).

- Palestine Census 1931.

- Andrea Pacini (1998). Socio-Political and Community Dynamics of Arab Christians in Jordan, Israel, and the Autonomous Palestinian Territories. Clarendon Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0.

- "Bethlehem". Archived from the original on July 29, 2013.

- "Palestinian Population by Locality and Refugee Status". Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "2007 PCBS Census" (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. p. 117. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- Bethlehem, The Holy Land's Collective Cultural National Identity: A Palestinian Arab Historical Perspective Musallam, Adnan. Bethlehem University. Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Malek, Cate (April 4, 2017). "Bethlehem is Struggling to Protect the Church of the Nativity". Newsweek. The Newsweek Daily Beast Company. Archived from the original on February 29, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Lidman, Melanie (December 24, 2016). "Christians Worry 'Silent Night' May Soon Refer to their own Community in Bethlehem". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- O'Connor, Anne-Marie (December 21, 2013). "Little Palestinian town of Bethlehem wants its tourists, Christian residents to come back". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company LLC. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Jim Teeple (December 24, 2005). "Christians Disappearing in the Birthplace of Jesus". Voice of America. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- Raab, David (January 5, 2003). "The Beleaguered Christians of the Palestinian-Controlled Areas: Official PA Domination of Christians". Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- Shragai, Nadav (December 26, 2012). "Why are Christians leaving Bethlehem?". Yisrael HaYom. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- "Americans not sure where Bethlehem is, survey shows". Ekklesia. December 20, 2006. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- Connor, Phillip; Hackett, Conrad (May 19, 2014). "Middle East's Christian population in flux as Pope Francis visits Holy Land". pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on February 2, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Marsh, Leonard (July 2005). "Palestinian Christianity – A Study in Religion and Politics". International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church. 57 (7): 147–66. doi:10.1080/14742250500220228. S2CID 143729196.

- "Report on Christian Emigration: Palestine". Holy Land Christian Ecumenical Foundation. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014.

- "Bethlehem Municipality(Site Under Construction)". Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Bethlehem: Shopping". TouristHub. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- "Handicrafts: Olive-wood carving". Bethlehem Municipality. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007.

- "Bethlehem Information". Bethlehem Chamber of Commerce & Industry. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- Jahsan, Ruby. "Wine". The Centre for Cultural Heritage Preservation. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- Palestinians bidding for business Maqbool, Aleem. BBC News. BBC. May 21, 2008. Retrieved on 2008-05-22. Archived January 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "The City Economy". Bethlehem Municipality. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- "Bethlehem's struggles continue". Al Jazeera English. December 25, 2007. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- Patience, Martin (December 22, 2007). "Better times return to Bethlehem". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- Jacir Palace, InterContinental Bethlehem re-opens for business InterContinental Hotels Group Archived December 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press 1999, page 38.

- Freed, 2004, p. 77. (citing Micah 5:2)

- Taylor, 1993, pp. 99–100. "Joseph ... took up his quarters in a certain cave near the village; and while they were there Mary brought forth the Christ and placed him in a manger, and here the Magi who came from Arabia found him."(Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, chapter LXXVIII).

- In Bethlehem the cave is pointed out where he was born, and the manger in the cave where he was wrapped in swaddling clothes. And the rumor is in those places, and among foreigners of the Faith, that indeed Jesus was born in this cave who is worshipped and reverenced by the Christians. (Origen, Contra Celsum, book I, chapter LI).

- Taylor, 1993, pp. 96–104./ref> Many modern scholars question the idea that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, seeing the biblical stories not as historical accounts but as symbolic narratives invented to present the birth as fulfillment of prophecy and imply a connection to the lineage of King David.ref>Vermes, 2006, p. 22.

- Sanders, 1993, p. 85.

- Crossan and Watts, p. 19.

- Dunn, 2003, pp. 344–345.

- Marcus J. Borg, Meeting Jesus for the First Time (Harper San Francisco, 1995) page 22–23.

- Mills and Bullard, 1990, pp. 445–446. See Mark 6:1–4 Archived November 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; and John 1:46 Archived December 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- Aviram Oshri, "Where was Jesus Born?", Archaeology, Volume 58 Number 6, November/December 2005.

- Jerome Murphy-O'Connor, Bethlehem ... Of Course Archived March 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Biblical Archaeology Review. ; see also A. Puig i Tàrrech, "The Birth of Jesus and History: The Interweaving of the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke", B. Estrada, E. Manicardi, A. Puig i Tàrrech (ed.), ≤The Gospels, History and Christology. The Search of Joseph Ratzinger≥, Vatican City:LEV, 2013, 353–97.

- "Christmas in Bethlehem". Sacred Destinations. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- St. George's Feast Bethlehem.ps.

- "Palestine costume before 1948: by region". Palestine Costume Archive. Archived from the original on September 13, 2002. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- Stillman, Yedida Kalfon (1979). Palestinian costume and jewelry. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8263-0490-2.

- "Tourist Products". Palestine-Family.net. January 23, 2007. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- Weir, pp. 128, 280, n.30

- A Description of the East and Some other Countries, p. 436

- "Palestinian Heritage Center: Objectives". Archived from the original on November 12, 2007.

- "The Edward Said National Conservatory of Music". Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- Municipal Council Elections during the British and Jordanian Periods Archived August 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Bethlehem Municipal Council.

- "Bethlehem Municipality(Site Under Construction)". Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- Kuttab, Daoud (December 23, 2012). "Bethlehem Has New Female Mayor, Yet Same Old Problems". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- "Municipalities Info". Archived from the original on February 21, 2007.

- "Bethlehem Municipality". Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Palestinian Population (10 Years and Over) by Locality, Sex and Educational Attainment". Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Statistics about General Education in Palestine 2005–2006" (PDF). Education Minister of the Palestinian National Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2008.

- "Mission and History". Bethlehem University. Archived from the original on February 7, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- "Bethlehem Public Transport System". Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2008. Bethlehem Municipality.

- "Impact of Israel's separation barrier on affected West Bank communities – OCHA update report #2". September 30, 2003. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- "Twinning Cities". bethlehem-city.org. Bethlehem. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Zaragoza Internacional". zaragoza.es (in Spanish). Zaragoza. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Jumelages". montpellier.fr (in French). Montpellier. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

Bibliography

- Albright, W. F. (October 1, 1936). "The Canaanite God Ḥaurôn (Ḥôrôn)". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 53 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1086/370495. ISSN 1062-0516. S2CID 170454212.

- Amara, Muhammad (1999). Politics and sociolinguistic reflexes: Palestinian border villages (Illustrated ed.). John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-4128-3.

- Brynen, Rex (2000). A very political economy: peacebuilding and foreign aid in the West Bank and Gaza (Illustrated ed.). US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1-929223-04-6.

- Crossan, John Dominic; Watts, Richard G. Who Is Jesus?: Answers to Your Questions About the Historical Jesus. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Dunn, J. (2003). Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- Freed, Edwin D. (2004). Stories of Jesus' Birth. Continuum International.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Klein, Konstantin (2018). "Bethlehem". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 5. Mercer University Press.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 978-1-84171-821-7. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012.

- Russell, James R. (1991). "CHRISTIANITY i. In Pre-Islamic Persia: Literary Sources". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. V, Fasc. 5. pp. 523–528. Archived from the original on November 17, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- Read, P.P. (2000). The Templars. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-26658-5.

- Sanders, E.P. (1993). "The Historical Figure of Jesus".

- Sawsan & Shomali, Q., Bethlehem 2000. A Guide to Bethlehem and it Surroundings. Waldbrol, Flamm Druck Wagener GMBH, 1997.

- Singer, A. (1994). Palestinian Peasants and Ottoman Officials: Rural Administration Around Sixteenth-Century Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47679-9. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Taylor, J.E. (1993). Christians and the Holy Places. Oxford University Press.

- Thomson, W.M. (1860). The Land and the Book.

- Vermes, G. (2006). The Nativity: History and Legend. Penguin Press.

External links

- Pastor's Vision to put Christ back in Bethlehem during Christmas

- Bethlehem Municipality

- Welcome To The City of Bethlehem

- Bethlehem Peace Center

- Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land website – pages on Bethlehem

- Bible Land Library*

- Open Bethlehem civil society project Archived April 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Bethlehem: Muslim-Christian living together Archived February 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Photo: Christmas in Bethlehem, 2008 Archived November 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Photo Gallery of Bethlehem from 2007

- Bethlehem Fair Trade Artisans

- Bethlehem University

- Bethlehem City (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem, ARIJ

- Bethlehem City Profile, ARIJ

- Bethlehem aerial photo, ARIJ

- The priorities and needs for development in Bethlehem city based on the community and local authorities' assessment, ARIJ