Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne (/seɪˈzæn/ say-ZAN, also UK: /sɪˈzæn/ sə-ZAN, US: /seɪˈzɑːn/ say-ZAHN;[1][2] French: [pɔl sezan]; 19 January 1839 – 22 October 1906) was a French artist and Post-Impressionist painter whose work introduced new modes of representation and influenced avant-garde artistic movements of the early 20th century. Cézanne is said to have formed the bridge between late 19th-century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism.

Paul Cézanne | |

|---|---|

Cezanne in 1899 | |

| Born | 19 January 1839 Aix-en-Provence, France |

| Died | 22 October 1906 (aged 67) Aix-en-Provence, France |

| Resting place | Saint-Pierre Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Académie Suisse Aix-Marseille University |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Mont Sainte-Victoire (1885–1906) Apothéose de Delacroix (1890–1894) Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier (1893–94) The Card Players (1890–1895) The Bathers (1898–1905) |

| Movement | Impressionism, Post-Impressionism |

| Awards | Cézanne medal |

While his early works are still influenced by Romanticism – such as the murals in the Jas de Bouffan country house – and Realism, Cézanne arrived at a new pictorial language through intensive examination of Impressionist forms of expression. He altered conventional approaches to perspective and broke established rules of academic art by emphasizing the underlying structure of objects in a composition and the formal qualities of art. Cézanne strived for a renewal of traditional design methods on the basis of the impressionistic colour space and colour modulation principles. Cézanne's often repetitive, exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. He used planes of colour and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields. The paintings convey Cézanne's intense study of his subjects. Both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso are said to have remarked that Cézanne "is the father of us all".

His painting provoked incomprehension and ridicule in contemporary art criticism. Until the late 1890s it was mainly fellow artists such as Camille Pissarro and the art dealer and gallery owner Ambroise Vollard who discovered Cézanne's work and were among the first to buy his paintings. In 1895, Vollard opened the first solo exhibition in his Paris gallery, which led to a broader examination of the artist's work.[3]

Life and work

Early years and family

Paul Cézanne was born the son of the milliner and later banker Louis-Auguste Cézanne and Anne-Elisabeth-Honorine Aubert at 28 rue de l'Opera in Aix-en-Provence. His parents only married after the birth of Paul and his sister Marie (born 1841) on 29 January 1844. His youngest sister Rose was born in June 1854. The Cézannes came from the commune of Saint-Sauveur (Hautes-Alpes, Occitania). Paul Cézanne was born on 19 January 1839 in Aix-en-Provence.[4] On 22 February, he was baptized in the Église de la Madeleine, with his grandmother and uncle Louis as godparents,[4][5][6][7] and became a devout Catholic later in life.[8] His father, Louis Auguste Cézanne (1798–1886),[9] a native of Saint-Zacharie (Var),[10] was the co-founder of a banking firm (Banque Cézanne et Cabassol) that prospered throughout the artist's life, affording him financial security that was unavailable to most of his contemporaries and eventually resulting in a large inheritance.[11]

His mother, Anne Elisabeth Honorine Aubert (1814–1897),[12] was "vivacious and romantic, but quick to take offence".[13] It was from her that Cézanne got his conception and vision of life.[13] He also had two younger sisters, Marie and Rose, with whom he went to a primary school every day.[4][14]

At the age of ten Cézanne entered the Saint Joseph school in Aix.[15] Classmates were the later sculptor Philippe Solari and Henri Gasquet, father of the writer Joachim Gasquet, who was to publish his book Cézanne in 1921, a testament to the life of the artist. In 1852 Cézanne entered the Collège Bourbon in Aix[16] (now Collège Mignet), where he became friends with Émile Zola, who was in a less advanced class,[11][14] as well as Baptistin Baille—three friends who came to be known as "Les Trois Inséparables" (The Three Inseparables).[17] It was probably the most carefree time of his life as the friends swam and fished on the banks of the Arc. They debated art, read Homer and Virgil and practiced writing their own poems. Cézanne often wrote his verses in Latin. Zola urged him to take poetry more seriously, but Cézanne saw it as just a pastime.[18] He stayed there for six years, though in the last two years he was a day scholar.[19] In 1857, he began attending the Free Municipal School of Drawing in Aix, where he studied drawing under Joseph Gibert, a Spanish monk.[20]

At the request of his authoritarian father, who traditionally saw in his son the heir to his bank Cézanne & Cabassol, Paul Cézanne enrolled in the law faculty of the University of Aix-en-Provence in 1859 and attended lectures for the study of jurisprudence. He spent two years with his unloved studies, but increasingly neglected them and preferred to devote himself to drawing exercises and writing poems. From 1859, Cézanne took evening courses at the École de dessin d'Aix-en-Provence, which was housed in the art museum of Aix, the Musée Granet. His teacher was the academic painter Joseph Gibert (1806–1884). In August 1859 he won second prize in the figure studies course there.[21]

His father bought the Jas de Bouffan (House of the Wind) estate that same year. This partly derelict baroque residence of the former provincial governor later became the painter's home and workplace for a long time.[22][23] The building and the old trees in the park of the property were among the artist's favorite subjects. In 1860, Cézanne obtained permission to paint the walls of the drawing room, and created the large-format murals of the four seasons: spring, summer, autumn and winter (today in the Petit Palais in Paris), which Cézanne ironically signed as Ingres, whose works he did not appreciate. The winter picture is additionally dated 1811, alluding to Ingres' painting Jupiter and Thetis, painted at that time and on display in the Musée Granet.[24]

Going against the objections of his banker father, he committed himself to pursue his artistic development and left Aix for Paris in 1861. He was strongly encouraged to make this decision by Zola, who was already living in the capital at the time and urged Cézanne to abandon his hesitancy and follow him there. Eventually, his father reconciled with Cézanne and supported his choice of career, on condition that he begin a regular course of study, having given up hope of finding Paul as his successor in the banking business. Cézanne later received an inheritance of 400,000 francs from his father, which rid him of all financial worries.[25]

Studies in Paris

Cézanne moved to Paris in April 1861. The high hopes he had set in Paris were not fulfilled, as he had applied to the École des Beaux-Arts, but was turned down there. He attended the free Académie Suisse, where he was able to devote himself to life drawing. There he met Camille Pissarro, ten years his senior, and Achille Emperaire from his hometown of Aix. He often copied at the Louvre from works by old masters such as Michelangelo, Rubens and Titian. But the city remained alien to him, and he soon thought of returning to Aix-en-Provence. Initially, the friendship formed in the mid-1860s between Pissarro and Cézanne was that of master and disciple, in which Pissarro exerted a formative influence on the younger artist. Over the course of the following decade, their landscape painting excursions together, in Louveciennes and Pontoise, led to a collaborative working relationship between equals.

Zola's faith in Cézanne's future was shaken, so in June he wrote to their childhood friend Baille: "Paul is still the excellent and strange fellow I knew at school. To prove that he hasn't lost any of his originality, I have only to tell you that as soon as he got here he talked about returning."[26] Cézanne painted a portrait of Zola that Zola had asked him to paint to encourage his friend; but Cézanne was unsatisfied with the result and destroyed the picture. In September 1861, disappointed by his rejection at the École, Cézanne returned to Aix-en-Provence and worked again in his father's bank.[27]

But already in the late autumn of 1862 he moved to Paris again. His father secured his subsistence level with a monthly bill of over 150 francs. The traditional École des Beaux-Arts rejected him again. He therefore attended the Académie Suisse again, which promoted Realism. During this time he got to know many young artists, after Pissarro also Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley.

In contrast to the official artistic life of France, Cézanne was under the influence of Gustave Courbet and Eugène Delacroix, who strove for a renewal of art and demanded the depiction of unembellished reality. Courbet's followers called themselves "realists" and followed his principle Il faut encanailler l'art ("One must throw art into the gutter"), formulated as early as 1849, which means that art must be brought down from its ideal height and become a matter of everyday life be made. Édouard Manet made the definitive break with historical painting, who was not concerned with analytical observation, but with the reproduction of his subjective perception and the liberation of the pictorial object from symbolic burdens.

The exclusion of the works of Manet, Pissarro and Monet from the official salon, the Salon de Paris, in 1863 provoked such outrage among artists that Napoleon III had a “Salon des Refusés” (salon of the rejected) set up next to the official salon. Cézanne's paintings were shown in the first exhibition of the Salon des Refusés in 1863. The Salon rejected Cézanne's submissions every year from 1864 to 1869. He continued to submit works to the Salon until 1882. In that year artist Antoine Guillemet, a friend of Cézanne's, became a member of the Salon jury. Since each jury member had the privilege of showing a picture of one of his students, he passed off Cézanne as his student and secured his first participation at the Salon. He exhibited Portrait de M. L. A., probably Portrait of Louis-Auguste Cézanne, The Artist's Father, Reading "L'Événement", 1866 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.),[28] although the painting was hung in a poorly lit spot in the top row of a secluded hall and received no attention. This was to be his first and last successful submission to the Salon.[29][30]

In 2022 a portrait was discovered beneath the 1865 Still Life with Bread and Eggs when the Cincinnati Art Museum's museum's chief conservator, Serena Urry, removing the painting from an exhibit in which it had been included and examining it for potential maintenance requirements, noticed unusual patterns in the cracking and "on a hunch" had it x-rayed.[31] Because Cézanne dated few paintings, it is believed to be the earliest firmly dated portrait by the artist.[32] Museum curators believe it is likely a self-portrait; if so it may also be one of the earliest depictions of the artist, who was in his 20s the year he painted the still life.[31]

In the summer of 1865, Cézanne returned to Aix. Zola's debut novel La Confession de Claude was published, it was dedicated to his childhood friends Cézanne and Baille. In the autumn of 1866, Cézanne executed a whole series of paintings using the palette knife technique, mainly still lifes and portraits. He spent most of 1867 in Paris and the second half of 1868 in Aix. At the beginning of 1869 he returned to Paris and met the bookbinder's assistant Marie-Hortense Fiquet, eleven years his junior, at the Académie Suisse[33]

L'Estaque – Auvers-sur-Oise – Pontoise 1870–1874

On 31 May 1870, Cézanne was best man at Zola's wedding in Paris. During the Franco-Prussian War, Cézanne and Hortense Fiquet lived in the fishing village of L'Estaque near Marseille, which Cézanne would later visit and paint frequently, as the place's Mediterranean atmosphere fascinated him. He avoided conscription for military service. Although Cézanne had been denounced as a deserter in January 1871, he managed to hide. No further details are known as documents from this period are missing.[34]

After the Paris Commune was crushed the couple returned to Paris in May 1871. Paul fils, the son of Paul Cézanne and Hortense Fiquet was born on 4 January 1872. Cézanne's mother was kept a party to family events, but his father was not informed of Hortense for fear of risking his wrath and so as not to lose the financial allowances that his father gave him to live as an artist. The artist received from his father a monthly allowance of 100 francs.[35]

When Cézanne's friend, the crippled painter Achille Emperaire, sought refuge with the family in Paris in 1872 due to financial hardship, he soon left his friend however "[...] it was necessary, otherwise I would not have escaped the fate of the others. I found him here abandoned by everyone. […] Zola, Solari and all the others are no longer mentioned. He's the strangest guy imaginable."[36]

From late 1872 to 1874, Cézanne lived with his wife and child in Auvers-sur-Oise, where he met the doctor and art lover Paul Gachet, later the painter Vincent van Gogh's doctor. Gachet was also an ambitious hobby painter and made his studio available to Cézanne.

In 1872, Cézanne accepted an invitation from his friend Pissarro to work in Pontoise in the Oise Valley. Pissarro, as a sensitive artist became a mentor to the shy, irritable Cézanne; he was able to persuade him to turn away from the darker colours on his colour palette and gave him the advice: "Always only paint with the three primary colours (red, yellow, blue) and their immediate deviations." In addition, he should refrain from linear contouring, the shape of things results from the gradation of the colour tonal values. Cézanne felt that the Impressionist technique was bringing him closer to his goal and heeded his friend's advice. Pissarro later reported: "We were always together, but still each of us kept what counts alone: our own feelings."[37]

First Impressionist group exhibitions from 1874

The young painters in Paris did not see any support for their works in the Salon de Paris and therefore took up Claude Monet's plan for their own exhibition, which had been made in 1867. From 15 April to 15 May 1874, the first group exhibition of the Société anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, engravers, later known as the Impressionists, took place. This name derives from the title of the exhibited painting Impression soleil levant by Monet. In the satirical magazine Le Charivari, the critic Louis Leroy described the group as "Impressionists" and thus created the term for this new art movement. The place of exhibition was the studio of the photographer Nadar on Boulevard des Capucines.

Pissarro pushed through Cézanne's participation despite concerns from some members who feared Cézanne's bold paintings would harm the exhibition. Cézanne was influenced by their style but his social relations with them were inept—he seemed rude, shy, angry, and given to depression. In addition to Cézanne, Renoir, Monet, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas and Pissarro, among others exhibited. Manet declined participation, for him Cézanne was "a mason who paints with a trowel".[38] Cézanne in particular caused a sensation, arousing indignation and derision from the critics with his paintings such as the Landscape near Auvers and the Modern Olympia.[39] In A Modern Olympia, created as a quote from Manet's 1863 painting Olympia, which was often reviled, Cézanne sought an even more drastic depiction and in addition to the prostitute and servant, also showed the suitor, whose figure is believed to be a self-portrait.[40]

The exhibition proved a financial failure; the final accounts showed a deficit of over 180 francs for each of the participating artists. Cézanne's The Hanged Man's House was one of the few pictures that could be sold. The collector Count Doria bought it for 300 francs.[41]

In 1875, Cézanne met the customs inspector and art collector Victor Chocquet, who, mediated by Renoir, bought three of his works and became his most loyal collector and whose commissions provided some financial relief. Cézanne did not take part in the group's second exhibition, but instead presented 16 of his works in the third exhibition in 1877, which in turn drew considerable criticism. Reviewer Louis Leroy said of Cézanne's portrait of Chocquet: "This peculiar looking head, the colour of an old boot might give [a pregnant woman] a shock and cause yellow fever in the fruit of her womb before its entry into the world."[42] It was the last time he exhibited with the Impressionists.[43] Another patron was the paint merchant Julien "Père" Tanguy, who supported the young painters by supplying them with paint and canvas in exchange for paintings.

In March 1878, Cézanne's father found out about the long-hidden relationship with Hortense and their illegitimate son Paul through a thoughtless letter by Victor Chocquet. He then cut the monthly bill in half, and Cézanne entered a financially tense period in which he had to ask Zola for help.[44] But in September he relented and decided to give him 400 francs for his family. Cézanne continued to migrate between the Paris region and Provence until Louis-Auguste had a studio built for him at his home, Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, in the early 1880s. This was on the upper floor, and an enlarged window was provided, allowing in the northern light but interrupting the line of the eaves; this feature remains. Cézanne stabilized his residence in L'Estaque. He painted with Renoir there in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.[45]

In 1881 Cézanne worked in Pontoise with Paul Gauguin and Pissarro; Cézanne returned to Aix at the end of the year. He later accused Gauguin of having stolen his "little sensation" from him and that Gauguin, on the other hand only painted chinoiseries.[46] In the spring of 1882, Cézanne worked with Renoir in Aix and – for the first time – in L'Estaque, a small fishing village near Marseille, which he also visited in 1883 and 1888. One of the first two stays was The Bay of Marseille seen from L'Estaque.[47] During the autumn of 1885 and the months that followed, Cézanne stayed in Gardanne, a small hilltop town near Aix-en-Provence, where he produced several paintings whose faceted forms were already anticipating the cubist style.

Break with Zola and marriage

Cézanne's long friendly relationship with Émile Zola had by now become more distant. In 1878 the urbane, successful writer had set up a luxurious summer house in Médan near Auvers, where Cézanne had visited him repeatedly in the years 1879 to 1882 and in 1885; but his friend's lavish lifestyle made Cézanne, who lived an unassuming life, aware of his own inadequacy and caused him to doubt himself.[48]

Zola, who meanwhile regarded the childhood friend as a failure, published his roman à clef L'Œuvre from the novel cycle of Rougon-Macquart in March 1886, whose protagonist, the painter Claude Lantier, did not achieve the realization of his goals and committed suicide. In order to further emphasize the parallels between fiction and biography, Zola placed the successful writer Sandoz alongside the painter Lantier in his work. Monet and Edmond de Goncourt tended to see Édouard Manet in the fictional painter described, but Cézanne found himself reflected in many details. He formally thanked him for sending the work supposedly related to him. For a long time it was thought that contact between the two childhood friends then broke off forever.[49][50] Recently letters have been discovered that refute this. A letter from 1887 demonstrates that their friendship did endure for at least some time after.[51][52]

_in_a_Red_Dress%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_116.5_x_89.5_cm%252C_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art%252C_New_York.jpg.webp)

On April 28, 1886, Paul Cézanne and Hortense Fiquet were married in Aix in the presence of his parents. The connection to Hortense was not legalized out of love, as their relationship had long since broken down. Cézanne was shy of women and terrified of being touched, a trauma that stemmed from his childhood when, by his own admission, a classmate had kicked him from behind on the stairs.[53] Rather, the marriage was intended to secure the rights of the now fourteen-year-old son Paul, whom Cézanne loved very much, as a legitimate son. In the early 1880s the Cézanne family stabilized their residence in Provence where they remained, except for brief sojourns abroad, from then on. The move reflects a new independence from the Paris-centered impressionists and a marked preference for the south, Cézanne's native soil. Hortense's brother had a house within view of Montagne Sainte-Victoire at L'Estaque. A run of paintings of this mountain from 1880 to 1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885 to 1888 are sometimes known as "the Constructive Period".[54]

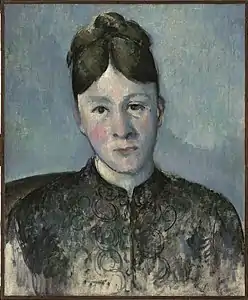

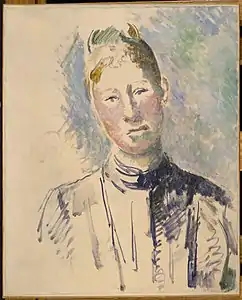

Despite the strained relationship, Hortense was the person who was most often portrayed by Cézanne. From the early 1870s to the early 1890s, 26 paintings of Hortense are known. She endured the strenuous sessions motionless and patiently. In October 1886, after the death of his father, Cézanne, his mother and sisters inherited his estate, which included the Jas de Bouffan estate, so that Cézanne's financial situation became much easier. "My father was a brilliant man," he said in retrospect, "he left me an income of 25,000 francs."[55] By 1888 the family was in the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, a substantial house and grounds with outbuildings, which afforded a new-found comfort. As of 2001, this house, with much-reduced grounds, is now owned by the city and was open to the public on a restricted basis.[56]

Exhibition at Les XX 1890 and first solo exhibition in Paris in 1895

Cézanne lived in Paris and increasingly in Aix without his family. Renoir visited him there in January 1888 and they worked together in Jas de Bouffan's studio. In 1890, Cézanne contracted diabetes; the illness made it even more difficult for him to deal with his fellow human beings. Cézanne spent a few months in Switzerland with her and his son Paul in the hope that the troubled relationship with Hortense could be stabilized. The attempt failed, so he returned to Provence, with Hortense and Paul fils going to Paris. Financial need prompted Hortense's return to Provence but in separate living quarters. Cézanne moved in with his mother and sister. In 1891 he turned to Catholicism.[57]

In the same year he exhibited three of his works at the group Les XX in Brussels. The Société des Vingt, short Les XX or Les Vingt, was an association founded around 1883 by Belgian artists or artists living in Belgium, including Fernand Khnopff, Théo van Rysselberghe, James Ensor and the siblings Anna and Eugène Boch.

In May 1895 he attended Monet's exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery with Pissarro. He was enthusiastic but later, significantly, identified 1868 as Monet's strongest period, when he was even more influenced by Courbet. With his fellow student from the Académie Suisse, Achille Emperaire, Cézanne went to the area around the village of Le Tholonet, where he lived in the "Château Noir", which is located on the Montagne Sainte-Victoire. He often took the mountains as a theme in his paintings. He rented a hut at the nearby Bibémus quarry; Bibémus became another motif for his paintings.

Ambroise Vollard, an aspiring gallery owner, opened Cézanne's first one-man show in November 1895. In his gallery, he showed a selection of 50 of around 150 works that Cézanne had sent him as a package. Vollard met Degas and Renoir in 1894 when he was exhibiting a bundle of Manet in his small shop, and they exchanged Manet works for their own works with him. Vollard also established relationships with Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard, and in the same year the well-known paint dealer Père Tanguy. When Tanguy died, Vollard was able to buy works by three artists who were still unknown at the time: Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh. The first buyer of a Cézanne painting was Monet, followed by colleagues like Degas, Renoir, Pissarro and later art collectors. Prices for works by Cézanne rose a hundredfold and Vollard, as always, profited from his stocks.[58]

In 1897, a Cézanne painting was purchased by a museum for the first time. Hugo von Tschudi acquired Cézanne's landscape painting The Mill on the Couleuvre near Pontoise in the Durand-Ruel Gallery for the Berlin National Gallery.

Cézanne's mother died on 25 October 1897. In November 1899, at the insistence of his sister, he sold the now practically deserted property "Jas de Bouffan" and moved into a small city apartment at 23, Rue Boulegon in Aix-en-Provence; the planned purchase of the “Château Noir” property could not be realized. He hired a housekeeper, Mme Bremond, to look after him until his death.

Homage to Cézanne

The art market, meanwhile continued to react positively to Cézanne's works; Pissarro wrote from Paris in June 1899 about the auction of the Chocquet collection from his estate: “These include thirty-two Cézannes of the first rank [...]. The Cézannes will fetch very high prices and are already estimated at four to five thousand francs.” In this auction, market prices for Cézanne paintings were achieved for the first time, but they were still “far below those for paintings by Manet, Monet or Renoir.”[59]

In 1901 Maurice Denis exhibited his 1900 large painting Hommage à Cézanne in Paris and Brussels. The subject of the picture is Ambroise Vollard's gallery, which presents a picture – Cézanne's painting Still Life with Bowl of Fruit – formerly owned by Paul Gauguin. The writer André Gide acquired Hommage à Cézanne and gave it to the Musée du Luxembourg in 1928. It is currently in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Among the people portrayed: Odilon Redon is in the foreground on the left, listening to Paul Sérusier opposite him. Also depicted from left to right are Édouard Vuillard, the critic André Mellerio with a top hat, Vollard behind the easel, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, Ker-Xavier Roussel, Pierre Bonnard with a pipe, and on the far right Marthe Denis, the painter's wife.[60]

Last years

In 1901, Cézanne acquired a piece of land north of the city of Aix-en-Provence along the Chemin des Lauves, an isolated road on some high ground, where he had his studio built on the Chemin des Lauves in 1902 according to his needs (Atelier de Cézanne, now open to the public). He moved there in 1903. For large-format paintings such as The Bathers, which he created in the Les Lauves studio, he had a long, narrow gap in the wall built through which natural light could flow. That year Zola died, leaving Cézanne in mourning despite the estrangement. His health deteriorated with age; In addition to his diabetes, he suffered from depression in old age, which manifested itself in growing distrust of his fellow human beings to the point of delusions of persecution.

Despite the artist's increasing recognition, hateful press releases appeared and he received numerous threatening letters.[61] Cézanne's paintings were not well received among the petty bourgeoisie of Aix. In 1903 Henri Rochefort visited the auction of paintings that had been in Zola's possession and published on 9 March 1903 in L'Intransigeant a highly critical article entitled "Love for the Ugly".[62] Rochefort describes how spectators had supposedly experienced laughing fits, when seeing the paintings of "an ultra-impressionist named Cézanne".[62] The public in Aix was outraged, and for many days, copies of L'Intransigeant appeared on Cézanne's door-mat with messages asking him to leave the town "he was dishonouring".[63] "I don't understand the world and the world doesn't understand me, so I withdrew from the world," said old Cézanne to his coachman.[64] When Cézanne deposited his will with a notary in September 1902, he excluded his wife Hortense from the inheritance and declared his son Paul to be the sole heir. Hortense is said to have burned the mementos of his mother.[65]

In 1903 he exhibited for the first time at the newly established Salon d'Automne (Paris Autumn Salon). The painter and art theorist Émile Bernard first visited him for a month in February 1904 and published an article about the painter in L'Occident magazine in July. Cézanne was then working on a vanitas still life with three skulls on an oriental carpet. Bernard reported that this painting changed colour and form every day during his stay, although it appeared complete from day one. He later regarded this work as Cézanne's legacy and summed it up: "Truly, his way of working was a reflection with a brush in his hand."[66] In the memento mori still lifes that he created several times, Cézanne's increasing depression of old age was evident, which in his letters since 1896 with comments such as "life is beginning to be deadly monotonous for me" were echoed.[67] An exchange of letters with Bernard continued until Cézanne's death; he first published his memoirs Souvenirs sur Paul Cézanne in the Mercure de France in 1907, and in 1912 they appeared in book form.

From 15 October to 15 November 1904, an entire room of the Salon d'Automne was furnished with the works of Cézanne. In 1905 an exhibition was held in London, in which his work was also shown; the Galerie Vollard exhibited his works in June, and the Salon d'Automne followed in turn from 19 October to 25 November with 10 paintings. The art historian and patron Karl Ernst Osthaus, who had founded the Museum Folkwang in 1902, visited Cézanne on 13 April 1906 in the hope of being able to purchase a painting by the artist. His wife Gertrud probably took the last photograph of Cézanne.[68] Osthaus described his visit in his work A Visit to Cézanne, published in the same year.

Despite the later successes, Cézanne was only ever able to approach his goals. On 5 September 1906, he wrote to his son Paul: "Finally, I want to tell you that as a painter I am becoming more clairvoyant to nature, but that it is always very difficult for me to realize my feelings. I cannot reach the intensity that unfolds before my senses, I do not possess that wonderful richness of colour that animates nature."[69]

Death

On 15 October 1906, Cézanne was caught in a storm while working in the field.[70] After working for two hours he decided to go home; but on the way he collapsed and lost consciousness. He was taken home by a passing driver of a laundry cart.[70] Due to hypothermia, he contracted severe pneumonia. His old housekeeper rubbed his arms and legs to restore the circulation; as a result, he regained consciousness.[70] The next day, Cézanne went out into the garden[71] to work on his last painting, Portrait of the Gardener Vallier, and wrote an impatient letter to his paint dealer, bemoaning the delay in the delivery of paint, but later on he fainted. Vallier with whom he was working called for help; he was put to bed, and he never left it.[70] His wife Hortense and son Paul received a telegram from the housekeeper, but they were too late. He died a few days later, on 22 October 1906[70] of pneumonia at the age of 67, and was buried at the Saint-Pierre Cemetery in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence.[72]

Main periods of Cézanne's work

Various periods in the work and life of Cézanne have been defined.[73]

Dark period, Paris, 1861–1870

Cézanne's early "dark" period was influenced by the works of French Romanticism and early Realism. Models were Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet. His paintings are characterized by a thick application of paint, high-contrast, dark tones with pronounced shadows, the use of pure black and other tones mixed with black, brown, gray and Prussian blue; occasionally a few white dots or green and red brushstrokes are added to brighten up, enlivening the monochrome monotony.[74] The themes of his pictures from this period are portraits of family members or demonic-erotic content, in which his own traumatic experiences are reminiscent.They differ sharply from his earlier watercolours and sketches at the École Spéciale de dessin at Aix-en-Provence in 1859, and their violence of expression is in contrast to his subsequent works.[75]

In 1866–67, inspired by the example of Courbet, Cézanne painted a series of paintings with a palette knife. He later called these works, mostly portraits, une couillarde ("a coarse word for ostentatious virility").[76] Lawrence Gowing has written that Cézanne's palette knife phase "was not only the invention of modern expressionism, although it was incidentally that; the idea of art as emotional ejaculation made its first appearance at this moment".[76]

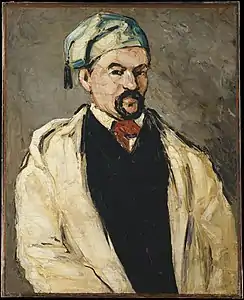

Among the couillarde paintings are a series of portraits of his uncle Dominique in which Cézanne achieved a style that "was as unified as Impressionism was fragmentary".[77] Later works of the dark period include several erotic or violent subjects, such as Women Dressing (c. 1867), The Abduction (c. 1867), and The Murder (c. 1867–68), which depicts a man stabbing a woman who is held down by his female accomplice.[78]

Impressionist period, Provence and Paris, 1870–1878

Camille Pissarro lived in Pontoise. There and in Auvers he and Cézanne painted landscapes together. For a long time afterwards, Cézanne described himself as Pissarro's pupil, referring to him as "God the Father", as well as saying: "We all stem from Pissarro."[79] Under Pissarro's influence Cézanne began to abandon dark colours and his canvases grew much brighter,[80] and he now used a colour palette based purely on the basic tones, yellow, red and blue. In doing so, he broke away from his technique of heavy, often overloaded-looking application of paint and adopted the loose painting technique of his role models, consisting of brushstrokes placed side by side.

Portraits and figurative compositions receded in these years. Cézanne subsequently created landscape paintings in which the illusionistic deep space was canceled more and more clearly. The “objects” continue to be understood as volumes and reduced to their basic geometric shapes. This design method is transferred to the entire picture area. The painterly gesture now treats the “distance” in a similar way to the “objects” themselves, giving the impression of a long-distance effect. In this way, Cézanne left the traditional pictorial space on the one hand, but on the other hand counteracted the dissolving impression of Impressionist pictorial works.

Mature period, Provence, 1878–1890

The "period of synthesis" followed, in which Cézanne completely broke away from the Impressionist style of painting. He solidified the forms by applying paint diagonally across the surface, eliminated the perspective representation to create the depth of the picture and directed his attention to the balance of the composition. During this period he increasingly created landscape and figure paintings. In a letter to his friend Joachim Gasquet he wrote: "The coloured surfaces, always the surfaces! The colourful place where the soul of the surfaces trembles, the prismatic warmth, the encounter of the surfaces in the sunlight. I design my surfaces with my shades on the palette, understand me! […] The areas must be clearly visible. Definitely [...] but they have to be distributed correctly, they have to flow into one another. Everything has to play together and yet create contrasts. It's all about the volume!"[81]

_-_BF20_-_Barnes_Foundation.jpg.webp)

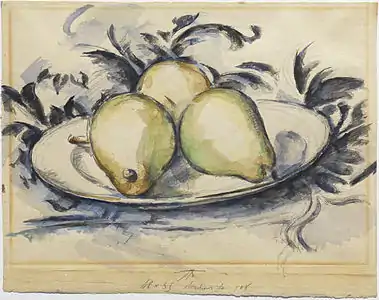

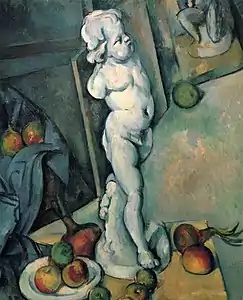

The still lifes that Cézanne painted from the late 1880s are another focus of his work. He refrained from rendering the motifs in linear perspective and instead depicted them in the dimensions that made sense to him in terms of composition; a pear, for example, can be oversized in order to achieve inner balance and an exciting composition. He built his arrangements in the studio. In addition to the fruit, there are jugs, pots and plates, and occasionally a putto, often surrounded by a white, puffy tablecloth that lends the subject a baroque opulence. It is not the objects that should attract attention, but the arrangement of the shapes and colours on the surface.

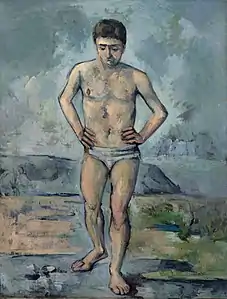

Cézanne developed the composition from individual dabs of paint spread across the canvas, from which the form and volume of the object gradually build up. Achieving the balance of these patches of colour on the canvas required a slow process, so Cézanne often worked on a painting for a long time.[82] Initially only portraying family members or friends, Cézanne's better financial position allowed him to hire a professional model, a young Italian named Michelangelo di Rosa, for The Boy in the Red Vest (1888–1890), one of his best-known paintings. Di Rosa was represented in four paintings and two watercolours.[83]

Final period, Provence, 1890–1906

Many of his later works, the so-called "lyrical period", such as the cycle of the bathers, are characterized by a turn to freely invented figures in the landscape; Cézanne created about 140 paintings and sketches on the theme of the bathing scenes. Here you can find his admiration for classical painting, which seeks to unite man and nature in harmony in Arcadian idylls. In the last seven years he created three large-format versions of The Great Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), with the 208 × 249 cm work on display in Philadelphia being the largest. Cézanne was concerned with the composition and the interplay of shapes and colours, of nature and figures. For his paintings at this time he used sketches and photographs as templates, since he did not like the presence of naked models.[84]

%252C_60_x_73_cm%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_Courtauld_Institute_of_Art%252C_London.jpg.webp)

Cézanne painted five versions of The Card Players (Les Joueurs de cartes) in 1890 and 1895, in which the same person is represented in different variants. For The Card Players, he used farmers and day laborers who worked in the fields near the Jas de Bouffan as models. They are not genre pictures, even if they show scenes from everyday life; the motif is constructed according to strict laws of colour and form.

The area around the Montagne Sainte-Victoire was one of the most important themes of his later years. From a vantage point above his studio, later called Terrain des Paintres, he painted several views of the mountain. A precise observation of nature was a prerequisite for Cézanne's painting: "In order to paint a landscape correctly, I first have to recognize the geological stratification."[85] In total he painted more than 30 oil paintings and 45 watercolours of the mountains, and he wrote to a friend in the 1890s "art is a harmony parallel to nature".[86]

Cézanne was primarily concerned with watercolour painting in his late work, as he realized that the specific application of his method could be particularly evident in this medium. The late watercolours also had an effect on his oil paintings, for example in the study with bathers (1902–1906), in which a depiction full of “empty spaces” flanked by colour appears to be complete.[87] The painter and art critic Roger Fry emphasized this in his seminal Cézanne publication Cézanne: A Study of His Development from 1927 that after 1885 the watercolour technique had a strong influence on his painting with oil paints. The watercolours in Vollard's Cézanne monograph of 1914 and in Julius Meier-Graefe's picture portfolio edited in 1918 with ten facsimiles based on the watercolours became known to a larger group of interested parties.[88] Only lightly coloured pencil studies, which occasionally appeared in sketch albums, stand next to carefully coloured works. Many watercolours are equal to the realizations on canvas and form an autonomous group of works. In terms of subject matter, landscape watercolours dominate, followed by figure paintings and still lifes, while portraits, in contrast to paintings and drawings, are rarer.[89]

Method

Artistic style

Cézanne's early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape and includes many paintings of groups of large, heavy figures in the landscape, imaginatively painted. Later in his career, he became more interested in working from direct observation and gradually developed a light, airy painting style. Nevertheless, in Cézanne's mature work there is the development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. Throughout his life he struggled to develop an authentic observation of the seen world by the most accurate method of representing it in paint that he could find. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and colour planes. His statement "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums",[90] and his contention that he was recreating Poussin "after nature" underscored his desire to unite observation of nature with the permanence of classical composition.

As with the old masters, for Cézanne the basis of painting was drawing, but the prerequisite for all work was subordination to the object, or the eye or pure looking: "All the painter’s intentions must be silent. He should silence all voices of prejudice. Forget! Forget! create silence! Be a perfect echo. […] The landscape is reflected, becomes human, thinks in me. […] I climb with her to the roots of the world. we germinate A tender excitement seizes me and from the roots of this excitement then rises the juice, the colour. I was born in the real world. I see! […] In order to paint that, then, the craft must be used, but a humble craft that obeys and is ready to transmit unconsciously."[91]

In addition to oil paintings and watercolours, Cézanne left behind an extensive oeuvre of more than 1200 drawings, which, hidden in the cupboards and folders of the studio during his lifetime only began to interest collectors in the 1930s. They form the working material for his works and show detailed sketches, observation notes and traces of Cézanne's sometimes difficult to decipher stages on the way to the realization of the picture. Their task, linked to the process of creating the respective work, was to give the overall structure and the object designations within the pictorial organism. Even in old age, portraits and figure drawings were made based on models from antique sculptures and baroque paintings from the Louvre, which gave him clarity about the isolation of plastic phenomena. Therefore, the black and white of the drawings was an essential prerequisite for Cézanne's colour designs.[92]

Paul Cézanne was the first artist to begin breaking down objects into simple geometric shapes. In his much-quoted letter of 15 April 1904 to the painter and art theorist Émile Bernard, who had met Cézanne in his last years, he wrote: "Treat nature according to cylinder, sphere, and cone and put the whole in perspective, like this that each side of an object, of a surface, leads to a central point […]"[93] Cézanne realized his painting ideas in the paintings of Montagne Sainte-Victoire and his still-lifes. In his pictorial conception, even a mountain is understood as a superimposition of forms, spaces and structures that rise above the ground.[94]

Émile Bernard wrote of Cézanne's unusual way of working: "He began with the shadow parts and with one spot, on which he put a second, larger one, then a third, until all these shades, covering each other, modelled the object with their colouring. It was then that I realized that a law of harmony was guiding his work and that these modulations had a direction preordained in his mind.”[95] In this preordained direction, for Cézanne, lay the real secret of painting in the context of harmony and the illusion of depth. To the collector Karl Ernst Osthaus Cézanne emphasized on 13 April 1906 during his visit to Aix that the main thing in a picture is the meeting of the distance. The colour must express every leap into the depths.[96]

Optical phenomena

Cézanne was interested in the simplification of naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials: he wanted to "treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone"[97] (a tree trunk may be conceived of as a cylinder, an apple or orange a sphere, for example). Additionally, Cézanne's desire to capture the truth of perception led him to explore binocular vision graphically, rendering slightly different, yet simultaneous visual perceptions of the same phenomena to provide the viewer with an aesthetic experience of depth different from those of earlier ideals of perspective, in particular single-point perspective. His interest in new ways of modelling space and volume derived from the stereoscopy obsession of his era and from reading Hippolyte Taine’s Berkelean theory of spatial perception.[98][99] Cézanne's innovations have prompted critics to suggest such varied explanations as sick retinas,[100] pure vision,[101] and the influence of the steam railway.[102]

Aller sur le motif, sensation and realization

Cézanne preferred to use these terms when describing his painting process. First of all, there is the "motif", by which he not only meant the representational concept of the picture, but also the motivation for his tireless work of observing and painting. Aller sur le motif, as he called his approach to work, therefore meant entering into a relationship with an external object that moved the artist inwardly and that had to be translated into a picture.

Sensation is another key term in Cézanne's vocabulary. First of all, he meant visual perception in the sense of "impression", i.e. an optical sensory stimulus emanating from the object. At the same time, it includes the emotion as a psychological reaction to what is perceived. Cézanne expressly did not place the object to be depicted at the center of his painterly efforts, but rather the sensation: "Painting from nature does not mean copying the object, it means realizing its sensations." The medium that mediated between things and sensations was the colour, although Cézanne left it open to what extent it arises from things or is an abstraction of his vision.

Cézanne used the third term réalisation to describe the actual painterly activity, which he feared would fail to the end. Several things had to be “realized” at the same time: first the motif in all its diversity, then the feelings that the motif triggered in him, and finally the painting itself, the realization of which could bring the other “realizations” to light. "Painting" therefore meant letting those opposing movements of taking in and giving, of "impression" and "expression" merge into one another in a single gesture.[103] The "realization in art" became a key concept in Cézanne's thinking and acting.

Dating and cataloguing

The sometimes longer dates for creation in the catalogues of Cézanne's works do not always indicate that the exact dating cannot be clarified, even if Cézanne rarely dated his pictures, especially since he worked on some pictures for months if not years before he was satisfied with the result.[104] The artist himself regarded many of his paintings as unfinished, for painting was a never-ending process for him.

Cataloging Cézanne's works turned out to be a difficult task. Ambroise Vollard made the first attempt, a multi-volume photo album, similar to his catalogue of Renoir. Vollard's catalogue never materialized however. Georges Rivière, the father-in-law of Cézanne's son published a biography of the artist in 1923 (Le Maître Paul Cézanne) that included a chronological and annotated list of many of the painter’s works. Conceived by the art dealer Paul Rosenberg, the first complete catalogue raisonné was published by Lionello Venturi in 1936. The two volume Cézanne: Son Art, Son Oeuvre became the definitive catalogue of the artist's work for over five decades, although requiring a supplement as additional works were discovered and new scholarship and documentation introduced. Adrien Chappuis' The Drawings of Paul Cézanne – A Catalog Raisonné was published by Thames and Hudson in London in 1973 and has remained the classic source for the artist's graphic work.[105]

John Rewald continued Venturi's work after his death. Rewald was tasked with combining Venturi’s planned supplement with his own research, an agreement that did not work out as intended. After years of studying Cézanne’s works, Rewald found that he not only disagreed with many of his predecessor’s dates but a number of his attributions as well. He therefore set about developing an entirely new catalogue raisonné.[105] Rewald's Paul Cézanne – The Watercolours: A Catalog Raisonné was published by Thames and Hudson, London with 645 illustrations in 1983. The missing dating of the paintings (Rewald only found one) and imprecise formulations of the pictorial motif such as Paysage or Quelques pommes caused confusion. In his early treatment of the Venturi Rewald made a list of all the works that could be dated without a stylistic analysis, because Rewald rejected such an analysis as unscientific. He continued his list by following the various whereabouts of Cézanne that could be verified by documents. Another scheme of his approach was to rely on the memories of the people portrayed, especially if they were Cézanne's contemporaries. Based on his own interviews, he made chronological assignments. Among the works that could be dated with certainty were Cézanne's Portrait of the Critic Gustave Geffroy, which the sitter confirmed as 1895, and Lake Annecy, which the artist visited only once, in 1896.

Rewald died in 1994, he was not able to fully complete his work. When in doubt, Rewald's tendency was to include rather than exclude. This method was adopted by his closest associates, Walter Feilchenfeldt Jr., son of the art dealer Walter Feilchenfeldt, and Jayne Warman, who completed the catalog and provided it with introductions. The catalog was published in 1996 under the title The Paintings of Paul Cézanne: A Catalog Raisonne – Review. It includes the 954 works that Rewald wanted to record.[106] Feilchenfeldt, Warman and David Nash went on to produce the first complete catalogue of the artist work since with The Paintings, Watercolours and Drawings of Paul Cézanne, an online catalogue raisonné.

Legacy

Testimonies of contemporary friends and painters

Yes, Cézanne, he is the greatest of us all![107]

Cézanne's childhood friend, the writer Émile Zola, was skeptical about Cézanne's human and artistic qualities, saying as early as 1861 that "Paul may have the genius of a great painter, but he will never have the genius to actually become one. The slightest obstacle drives him to despair."[108] In fact, it was Cézanne's self-doubt and refusal to make artistic compromises, as well as his rejection of social concessions, that led his contemporaries to regard him as an oddball.[109]

Cézanne's works were rejected numerous times by the official Salon in Paris and ridiculed by art critics when exhibited with the Impressionists. Yet during his lifetime, Cézanne was considered a master by younger artists who visited his studio in Aix.[110] In the circle of the Impressionists, however, Cézanne was given special recognition; Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet and Edgar Degas spoke enthusiastically about his work, and Pissarro said: "I think it will be centuries before we get an account of it."[111]

A portrait of Cézanne was painted by his friend and mentor Pissarro in 1874, and in 1901 the co-founder of the Nabis group, Maurice Denis, created Hommage à Cézanne, showing Cézanne's painting Still Life with Fruit[112] on the easel amidst artist friends at the Vollard Gallery. Originally owned by Paul Gauguin, Hommage à Cézanne was later acquired by French writer and Denis' friend, André Gide, who owned it until 1928. It is now on display at the Musée d'Orsay .

Contemporary art criticism

The first joint Impressionist exhibition, in Paris from April to May 1874, attracted extensive criticism. Audiences and art critics, for whom "the ideal" of the École de Beaux Arts was proof of the existence of art, burst out laughing. One critic claimed that Monet painted by loading his paints in a gun and shooting them at the canvas. A colleague performed an Indian dance in front of a painting by Cézanne and shouted: “Hugh! […] I am the walking impression, the avenging palette knife, Monet's 'Boulevard des Capucines', 'The House of the Hanged Man' and 'The Modern Olympia' by Mr. Cézanne. Hugh! Hugh![113]

In 1883, the French writer Joris-Karl Huysmans replied to Pissarro in a letter to Pissarro's accusation that Cézanne was only briefly mentioned in Huysman's book L'Art Moderne by suggesting that Cézanne's view of the motifs was distorted by astigmatism : "[...] but it There is certainly an eye defect involved, which I am assured he is also aware of.” Five years later, in La Cravache magazine, his judgment became more positive when he described Cézanne's works as “strange yet real” and as “revelations”. designated.[114]

The art dealer Ambroise Vollard first came into contact with Cézanne's works in 1892 through the paint dealer Tanguy, who had exhibited them in his shop in the Rue Clauzel in Montmartre in return for the delivery of painting utensils . Vollard recalled the lack of response: the shop was rarely visited, "since it was not yet fashionable at the time to buy 'atrocious works' expensively, not even cheaply." Tanguy even took interested parties to the painter's studio, to which he had a key where small pictures and 100 francs large pictures could be bought at a fixed price of 40 francs.[115] The Journal des Artistes echoed the general tone of the time, anxious to ask whether its sensitive readers would not be sickened at the sight of "these oppressive abominations, which exceed the measure of evil permitted by law."

The art critic Gustave Geffroy was one of the few critics who judged Cézanne's work fairly and unreservedly during his lifetime. As early as 25 March 1894, he wrote in the Journal about the then current relationship between Cézanne's painting and the efforts of younger artists, that Cézanne had become a kind of forerunner to which the Symbolists referred, and that there was a direct connection between Cézanne's painting and of the Gauguins, Bernards and even Vincent van Goghs. A year later, after the successful exhibition at the Vollard Gallery in 1895, Geffroy again led the Journal: "He is a great truth fanatic, fiery and naive, harsh and nuanced. He will go to the Louvre.” Between these two chronicles, Cézanne painted the portrait of Geffroy, which Cézanne left unfinished because he was dissatisfied with it.[116]

Posthumous exhibitions

Two retrospectives posthumously paid tribute to the artist in 1907. From 17 to 29 June, the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris showed 79 watercolours by Cézanne. The 5th Salon d'Automne then paid homage to him from 5 October to 15 November, exhibiting 49 paintings and seven watercolours in two rooms in the Grand Palais. Visitors included the art historian Julius Meier-Graefe, who would write the first Cézanne biography in 1910, Harry Graf Kessler and Rainer Maria Rilke. The two exhibitions motivated many artists, such as Georges Braque, André Derain, Wassily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, on their crucial insights for 20th century art.[117][118]

In 1910, some of Cézanne's paintings were shown in the Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition in London (another one followed in 1912). The exhibition had been initiated by the painter and art critic Roger Fry in the Grafton Galleries, which wanted to introduce English art lovers to the work of Édouard Manet, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin and Cézanne. Fry used the name to describe the Post-Impressionist style . Although the exhibition was judged negatively by critics and the public, it was to be significant in the history of modern art. Fry recognized the extraordinary value of the path that artists such as van Gogh and Cézanne had taken in expressing their personal feelings and worldview through their paintings, even if visitors at the time could not yet understand this.[119] Cézanne's first exhibition in the United States took place in 1910/11 at Gallery 291 in New York. In 1913 his works were exhibited at the Armory Show in New York ; it was a groundbreaking exhibition of modern art and sculpture, although here too the exhibits were met with criticism and ridicule. Today, these artists, who were criticized and ridiculed even by their own art academies during their lifetime, are regarded as the fathers of modern art.

Influence on modernity and misinterpretations

Cézanne! Cézanne was the father of all of us.

— Pablo Picasso[120]

A kind of dear god of painting.

— Henri Matisse[121]

Many "productive" misunderstandings lie hidden in the reception of the works and the supposed intentions of Cézanne, which had a considerable influence on the further course and development of modern art.[122] The list of those artists who more or less justifiably referred to him and who coined individual elements from the wealth of his creative approaches for their own pictorial inventions shows an almost complete art history of the 20th century. As early as 1910, Guillaume Apollinaire stated that "most of the new painters claim to be successors of this serious painter who was only interested in art".[123]

Immediately after Cézanne's death in 1906, stimulated by a comprehensive exhibition of his watercolours in the spring of 1907 at the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune and a retrospective in October 1907 at the Salon d'Automne in Paris, a lively examination of his work began.[124] Among young French artists, Henri Matisse and André Derain were the first to become passionate about Cézanne, followed by Picasso, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp and Piet Mondrian.[125] This enthusiasm was lasting, as the eighty-year-old Matisse said in 1949 that he owed the most to the art of Cézanne.[126] Braque also described the influence of Cézanne on his art as an "initiation" and said in 1961: "Cézanne was the first to turn away from the learned mechanized perspective."[127] Picasso admitted that "he was the only master for me ..., he was a father figure to us: it was he who offered us protection."[128]

Cézanne expert Götz Adriani notes, however, that the Cézanne's reception by Cubists – particularly by the Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, who placed Cézanne at the beginning of their way of painting in their 1912 treatise Du "Cubisme" – was arbitrary because they largely ignored the motivation gained from observing nature.[129] In this context, he points to the formalistic misinterpretations that refer to Émile Bernard's published paper from 1907, which refers to a 1904 letter Cézanne wrote advising him to "treat nature according to cylinder, sphere and cone"[130] Further misinterpretations of this kind can be found in Kazimir Malevich's 1919 text On the New Systems in Art.[131] In his quote, Cézanne did not intend to reinterpret the experience of nature in the sense of orienting himself towards cubic form elements; he was more concerned with corresponding to the object forms and their colouring under the various aspects in the picture.

One of the many examples of Cézanne's influence on modernism is the 1888 painting Mardi Gras in the Pushkin Museum, which shows his son Paul with his friend Louis Guillaume and in costumes from the Commedia dell'arte. Picasso took inspiration from it for the harlequin theme in his pink period. Matisse, in turn, took up the theme of the most classic painting in the Bathers series, The Great Bathers from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in his 1909 painting The Bathers.[132]

Numerous artists were inspired by Cézanne's work.[133] The painter Paula Modersohn-Becker saw Cézanne's paintings in Paris in 1900, which deeply impressed her. Shortly before her death, she wrote to Clara Westhoff in a letter on 21 October 1907 : "I am thinking and thinking a lot these days about Cézanne and how he is one of the three or four painters who struck me like a thunderstorm or a major event.”[134] Paul Klee noted in his diary in 1909: “Cézanne is a teacher par excellence for me” after seeing more than a dozen paintings by Cézanne in the Munich Secession.[135] The artist group Der Blaue Reiter referred to him in their 1912 almanac when Franz Marc reported on the kinship between El Greco and Cézanne, whose works he understood as the gateways to a new era of painting.[136] Again, Kandinsky, who had seen Cézanne's painting at the 1907 retrospective at the Salon d'Automne, refers to Cézanne in his 1912 treatise On the Spiritual in Art, in whose work he found a "strong resonance of the abstract." recognized and found the spiritual part of his beliefs predetermined in him.[137] El Lissitzky emphasized his importance for the Russian avant-garde around 1923, and Lenin suggested erecting monuments to the heroes of the world revolution in 1918; on the roll of honor were Courbet and Cézanne.[138] Next to Matisse, Alberto Giacometti dealt most extensively with Cézanne's style of representation. Aristide Maillol worked on a Cézanne monument in 1909, but failed due to rejection by the city of Aix-en-Provence.[139] Cézanne was also an important authority for artists of the newer generation. Jasper Johns described him as the most important role model alongside Duchamp and Leonardo da Vinci.

Inspired by Cézanne, Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger wrote:

Cézanne is one of the greatest of those who changed the course of art history ... From him we have learned that to alter the colouring of an object is to alter its structure. His work proves without doubt that painting is not—or not any longer—the art of imitating an object by lines and colours, but of giving plastic [solid, but alterable] form to our nature. (Du "Cubisme", 1912)[110][140]

Along with the work of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, the work of Cézanne, with its sense of immediacy and incompletion, critically influenced Matisse and others prior to Fauvism and Expressionism.[141][142] Cézanne's explorations of geometric simplification and optical phenomena inspired Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Gris and others to experiment with ever more complex views of the same subject and eventually to the fracturing of form. Cézanne thus sparked one of the most revolutionary areas of artistic enquiry of the 20th century, one which was to affect profoundly the development of modern art. Picasso referred to Cézanne as "the father of us all" and claimed him as "my one and only master!" Other painters such as Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Kasimir Malevich, Georges Rouault, Paul Klee, and Henri Matisse acknowledged Cézanne's genius.[110]

Ernest Hemingway compared his writing to Cézanne's landscapes.[143][144] As he describes in A Moveable Feast, I was "learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them."

Cézanne's painting The Boy in the Red Vest was stolen from a Swiss museum in 2008. It was recovered in a Serbian police raid in 2012.[145]

Films about Cézanne

Une visite au Louvre, 2004. Filmed and directed by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet about Cézanne, based on the posthumously published conversations with the painter, handed down by his admirer Joachim Gasquet. The film describes a walk by Cézanne in the Louvre past the paintings of his fellow artists.[146]

On the 100th anniversary of Cézanne's death in 2006, two documentaries from 1995 and 2000 about Paul Cézanne and his motif La Montagne Sainte-Victoire were re-released. Cézanne's triumph was re-shot for the 2006 anniversary year.[147]

The Violence of the Motive, 1995. A film directed by Alain Jaubert. A mountain near his hometown of Aix-en-Provence becomes Cézanne's main motif. He shows La Montagne Sainte-Victoire from different perspectives and at different times of the year more than 80 times. The motif becomes an obsession that Jaubert gets to the bottom of in his film.

Cézanne – the Painter, 2000. A film by Elisabeth Kapnist. The story of a passion and a lifelong artistic search: the painter Cézanne, his childhood, his friendship with Zola and his encounter with Impressionism are portrayed.

The Triumph of Cézanne, 2006. A film by Jacques Deschamps. Deschamps takes the 100th anniversary of Cézanne's death in October 2006 as an opportunity to trace the genesis of a legend. Cézanne encountered rejection and incomprehension before he was allowed to rise to the Olympus of art history and the international art market.

The 2016 film Cézanne and I explores the friendship between the artist and Émile Zola.[148]

Cézanne and philosophy

The French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard argues in his work Misère de la philosophie, that Cézanne has, so to speak, the sixth sense: he senses the reality in the making before it is completed in normal perception. So the painter touches on the sublime when he sees the overwhelming quality of the mountainous landscape, which can neither be represented with normal language nor with the usual painting technique. Lyotard sums it up: "One can also say that the uncanniness of the oil paintings and watercolours dedicated to mountains and fruits derives both from a deep sense of the disappearance of appearances and from the demise of the visible world."[149]

Cézanne's stylistic approaches and beliefs regarding how to paint were analyzed and written about by the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty who is primarily known for his association with phenomenology and existentialism.[150] In his 1945 essay entitled "Cézanne's Doubt", Merleau-Ponty discusses how Cézanne gave up classic artistic elements such as pictorial arrangements, single view perspectives, and outlines that enclosed colour in an attempt to get a "lived perspective" by capturing all the complexities that an eye observes. He wanted to see and sense the objects he was painting, rather than think about them. Ultimately, he wanted to get to the point where "sight" was also "touch". He would take hours sometimes to put down a single stroke because each stroke needed to contain "the air, the light, the object, the composition, the character, the outline, and the style". A still life might have taken Cézanne one hundred working sessions while a portrait took him around one hundred and fifty sessions. Cézanne believed that while he was painting, he was capturing a moment in time, that once passed, could not come back. The atmosphere surrounding what he was painting was a part of the sensational reality he was painting. Cézanne claimed: "Art is a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations and which I ask the understanding to organize into a painting."[151]

Art market

The increase in value of Cézanne's work can be seen from the auction of his painting Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier on 10 May 1999, which sold for $60.5 million at Sotheby's in New York,[152] the fourth-highest price paid for a painting up to that time, and the most expensive still life painting at the time.

Cézanne's watercolour Still Life with Green Melon set the record for a work on paper at an auction, when it sold for $25.5 million in 8 May 2007, far above its estimate of $18 million.[153] A preparatory watercolour for The Card Players series previously thought lost for sixty years sold for $19.1 million on 1 May 2012 to an anonymous bidder.[154]

One of the five versions of Cézanne's The Card Players was sold in 2011 to the Royal Family of Qatar for a price variously estimated at between $250 million ($325.2 million today) and possibly as high as $300 million ($390.3 million today), either price signifying a new mark for highest price for a painting up to that date. The record price was surpassed in November 2017 by Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci.[155][156] The Card Players is now the third most expensive painting of all time after the sale of Interchange by Willem de Kooning.

On 8 November 2022, $138 million US was paid for the painting La Montagne Sainte-Victoire as part of the Paul Allen collection sale at Christie's in New York City to setting a new mark for a price paid for his work at auction.[157]

Nazi-looted art

In 2000 French courts ordered the seizure of Cézanne's "The sea at l'Estaque" which was part of the "From Fra Angelico to Bonnard: masterpieces from the Rau Collection" exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg because of a claim that it had been looted by Nazis from the gallery owner Josse Bernheim-Jeune.[158]

In 2020 the provenance of a Cézanne from the Buehrle collection came under scrutiny.[159] The painting, Paysage, had already been flagged as potentially problematic in the 2015 Schwarzbuch Bührle: Raubkunst für das Kunsthaus Zürich?[160]. In Die Wochenzeitung, Keller said the provenance of Paysage had been "whitewashed". "Among Keller's objections to the provenance description on the foundation's website is the failure to note that the pre-war owners, Berthold and Martha Nothmann, were forced to flee Germany as Jews in 1939."[161]

Cézanne's Provence

Visitors to Aix-en-Provence can discover Cézanne's landscape motifs along five marked trails from the city center. They lead to Le Tholonet, the Jas de Bouffan, the Bibémus quarry, the banks of the River Arc and the Les Lauves workshop.[162]

The Atelier Les Lauves has been open to the public since 1954. An American foundation initiated by James Lord and John Rewald made this possible with funds provided by 114 donors. They bought it from the previous owner Marcel Provence and transferred it to the University of Aix. In 1969 the studio was transferred to the city of Aix. The visitor will find Cézanne's furniture, easel and palette, the objects that appear in his still lifes, and some original drawings and watercolours.

During their lifetime, most of the residents of Aix mocked their fellow citizen Cézanne. More recently, they even named a university after their world-famous artist: in 1973 it was founded in Aix-en-Provence, the Paul Cézanne University with the departments of law and political science, business administration as well as natural sciences and technology. In 2011 it was dissolved and combined with the other two universities in Aix and Marseille to form the University of Aix-Marseille.

As a result of their rejection of his works in the past, the Musée Granet in Aix had to make do with a loan of paintings from the Louvre in order to be able to present visitors with Cézanne, the son of their city. In 1984, the museum received eight paintings and some watercolours, including a motif from the Bathers series and a portrait of Mme Cézanne. Thanks to another donation in 2000, nine paintings by Cézanne are now on display there.[163]

Gallery

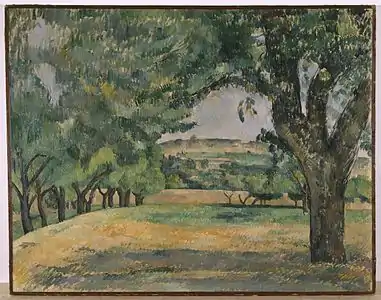

Landscapes

.jpg.webp)

L'Estaque

L'Estaque

1883–1885 Houses in Provence: The Riaux Valley near L'Estaque

Houses in Provence: The Riaux Valley near L'Estaque

1883 The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque

The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque

1885 The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan

1885-1887

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Thannhauser Collection

Still life paintings

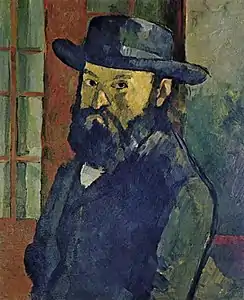

Portraits and self-portraits

_-_BF141_-_Barnes_Foundation.jpg.webp) Femme au Chapeau Vert (Woman in a Green Hat, Madame Cézanne) 1894–1895

Femme au Chapeau Vert (Woman in a Green Hat, Madame Cézanne) 1894–1895

Bathers

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Bathers,

Bathers,

1900-05,

Private collection

Watercolours

Boy with Red Vest

Boy with Red Vest

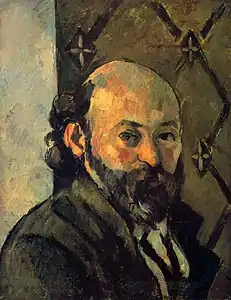

1890 Self-portrait

Self-portrait

1895 Three Pears, ca. 1888–1890, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Three Pears, ca. 1888–1890, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum The Plaster Kiln,

The Plaster Kiln,

1890-94,

Private collection Pine Tree in Front of the Caves above Château Noir, ca. 1900, Princeton University Art Museum

Pine Tree in Front of the Caves above Château Noir, ca. 1900, Princeton University Art Museum Mill at the River

Mill at the River

1900–1906 Study of a Skull, 1902–1904, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Study of a Skull, 1902–1904, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit, 1906, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

Still Life with Carafe, Bottle, and Fruit, 1906, Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection on long-term loan to the Princeton University Art Museum

See also

Notes

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Adriani, Götz. Cézanne: Life and Work. p. 110.

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 6

- Dominique Auzias, Le Petit Futé, 2008 p. 142 Archived 10 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Dominique Auzias, Jean-Paul Labourdette, Aix-en-Provence 2012, Le Petit Futé, 2012, p. 299 Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Olivier-René Veillon, Seul comme Cézanne, Maisonneuve et Larose, 1995, p. 24.

- "Paul Cézanne". TotallyHistory. June 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- "Louis Auguste Cézanne". Guarda-Mor, Edição de Publicações Multimédia Lda. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Danchev, Alex (2012). Cézanne: A Life. Pantheon. p. 45. ISBN 0307377075.

- "Paul Cézanne Biography (1839–1906)". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- "Louis Auguste Cézanne". Guarda-Mor, Edição de Publicações Multimédia Lda. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- A. Vollard First Impressions, p. 16

- A. Vollard, First Impressions, p. 14

- P. Machotka Narration and Vision, p. 9

- "Paul Cézanne | French artist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "National Gallery of Art timeline, retrieved 11 February 2009". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulricke. Cézanne. p. 7.

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 12

- Gowing 1988, p. 215

- P. Cézanne Paul Cézanne, letters, p. 10

- "Bastide du Jas de Bouffan". Cezanne in Provence. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulricke. Cézanne. p. 8.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulricke. Cézanne. p. 10.

- J. Lindsay Cézanne; his life and art, p. 232

- Leonhard, Kurt. Cézanne. p. 111.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulricke. Cézanne. p. 10.

- "The Artist's Father, Reading "L'Événement", 1866, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C". 1866. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- Gowing 1988, p. 110

- "Société des artistes français, catalogue illustré, Salon 1882, Cézanne, Portrait de M. L. A., p. 32, no. 520". 1879. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Feldman, Ella (19 December 2022). "For 158 Years, a Cézanne Portrait Hid Behind a Still Life of Bread and Eggs". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- "Cincinnati Art Museum discovers hidden work under a Cézanne painting in its collection". Cincinnati Art Museum. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- Adriani, Götz. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 121.

- Tillier, Bertrand (2013). La Commune de Paris, révolution sans images?. Seyssel. p. 84. ISBN 9782876733909.

- "Cézanne in Provence: A Provençal Chronology of Cézanne: 1870–1879" Archived 22 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 20.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 20.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 30.

- Leonhard, Kurt. Cézanne. p. 148.

- Adriani, Götz. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 17.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 34.

- Brion 1974, p. 34

- Leonhard, Kurt. Cézanne. p. 49.

- Adriani. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 30.

- "Cézanne in Provence: A Provençal Chronology of Cézanne: 1880–1889" Archived 15 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Bernard, Émile. Cézanne: On Art. p. 88.

- Adriani. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 123.

- Adrianni. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 32.

- Adrianni. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 33.

- "Paul Cézanne, Claude Lantier and Artistic Impotence, by Aruna D'Souza". Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- Elderfield, John; Morton, Mary; Rey, Xavier; Danchev, Alex; Warman, Jayne S. (2017). Cézanne Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery. p. 224. ISBN 9781855147317. OCLC 1006293797.

- Lethbridge, Robert (Winter 2014). "The End of the Affair: Zola and Cézanne". French Studies Bulletin. 35 (133): 95–99. doi:10.1093/frebul/ktu026.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 19.

- Anne Distel, Michel Hoog, Charles S. Moffett, Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archived 30 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 12 December 1974 – 10 February 1975, p. 56, ISBN 0870990977

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 50.

- Ulrike Becks-Malorny, Cézanne Archived 1 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Taschen, 2001, p. 48, ISBN 3822856428

- Susan Sidlauskas, Cézanne's Other: The Portraits of Hortense Archived 28 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, University of California Press, 2009, p. 240, ISBN 0520257456

- Tobias Timm (30 November 2006). "Der Mann, der Cézanne entdeckte". Die Zeit. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018.

- Adriani. Cézanne. Life and Work. p. 85.

- "Hommage à Cézanne". Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 17 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- Becks-Malorny. Cézanne. p. 81.

- Rochefort, Henri, L'Amour du laid, L'Intransigeant Archived 19 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Numéro 8272, 9 March 1903, Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France (French)

- The Unknown Matisse: A Life of Henri Matisse. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Leonhard, Kurt. Cézanne. p. 77.