Culture of India

Indian culture is the heritage of social norms and technologies that originated in or are associated with the ethno-linguistically diverse India. The term also applies beyond India to countries and cultures whose histories are strongly connected to India by immigration, colonisation, or influence, particularly in South Asia and Southeast Asia. India's languages, religions, dance, music, architecture, food and customs differ from place to place within the country.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

Indian culture, often labelled as a combination of several cultures, has been influenced by a history that is several millennia old, beginning with the Indus Valley civilization and other early cultural areas.[1][2] Many elements of Indian culture, such as Indian religions, mathematics, philosophy, cuisine, languages, dance, music and movies have had a profound impact across the Indosphere, Greater India, and the world According to Jean Przyluski, there is evidence for regional influence from Austroasiatic (Mon Khmer) groups on certain cultural and political elements of Ancient India, which may have arrived together with the spread of rice cultivation from Mainland Southeast Asia. An ethnic minority in Eastern India is still speaking Austroasiatic languages, most notably the Munda languages.[3][4] The British Raj further influenced Indian culture, such as through the widespread introduction of the English language,[5] and a local dialect developed.

Religious culture

| |||||

Indian-origin religions Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism,[6] are all based on the concepts of dharma and karma. Ahimsa, the philosophy of nonviolence, is an important aspect of native Indian faiths whose most well known proponent was Mahatma Gandhi, who used civil disobedience to unite India during the Indian independence movement – this philosophy further inspired Martin Luther King Jr. during the American civil rights movement. Foreign-origin religion, including Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, are also present in India,[7] as well as Zoroastrianism[8][9] and Baháʼí Faith[10][11] both escaping persecution by Islam[12][13][14] have also found shelter in India over the centuries.[15][16]

India has 28 states and 8 union territories with different culture and it is the most populated country in the world.[17] The Indian culture, often labeled as an amalgamation of several various cultures, spans across the Indian subcontinent and has been influenced and shaped by a history that is several thousand years old.[1][2] Throughout the history of India, Indian culture has been heavily influenced by Dharmic religions.[18] Influence from East/Southeast Asian cultures onto ancient India and early Hinduism, specifically Austroasiatic groups, such as early Munda and Mon Khmer, but also Tibetic and other Tibeto-Burmese groups, had noteworthy impact on local Indian peoples and cultures. Several scholars, such as Professor Przyluski, Jules Bloch, and Lévi, among others, concluded that there is a significant cultural, linguistic, and political Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) influence on early India, which can also be observed by Austroasiatic loanwords within Indo-Aryan languages and rice cultivation, which was introduced by East/Southeast Asian rice-agriculturalists using a route from Southeast Asia through Northeast India into the Indian subcontinent.[3][4] They have been credited with shaping much of Indian philosophy, literature, architecture, art and music.[19] Greater India was the historical extent of Indian culture beyond the Indian subcontinent. This particularly concerns the spread of Hinduism, Buddhism, architecture, administration and writing system from India to other parts of Asia through the Silk Road by the travelers and maritime traders during the early centuries of the Common Era.[20][21] To the west, Greater India overlaps with Greater Persia in the Hindu Kush and Pamir Mountains.[22] Over the centuries, there has been a significant fusion of cultures between Buddhists, Hindus, Muslims, Jains, Sikhs and various tribal populations in India.[23][24]

India is the birthplace of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, and other religions. They are collectively known as Indian religions.[25] Indian religions are a major form of world religions along with Abrahamic ones. Today, Hinduism and Buddhism are the world's third and fourth-largest religions respectively, with over 2 billion followers altogether,[26][27][28] and possibly as many as 2.5 or 2.6 billion followers.[26][29] Followers of Indian religions – Hindus, Sikhs, Jains and Buddhists make up around 80–82% population of India.

India is one of the most religiously and ethnically diverse nations in the world, with some of the most deeply religious societies and cultures. Religion plays a central and definitive role in the life of many of its people. Although India is a secular Hindu-majority country, it has a large Muslim population. Except for Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram and Lakshadweep, Hindus form the predominant population in all 27 states and 9 union territories. Muslims are present throughout India, with large populations in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Kerala, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal and Assam; while only Jammu and Kashmir and Lakshadweep have majority Muslim populations. Christians are other significant minorities of India.

Because of the diversity of religious groups in India, there has been a history of turmoil and violence between them. India has been a theatre for violent religious clashes between members of different religions such as Hindus, Christians, Muslims, and Sikhs.[30] Several groups have founded various national-religious political parties, and in spite of government policies minority religious groups are being subjected to prejudice from more dominant groups in order to maintain and control resources in particular regions of India.[30]

According to the 2011 census, 79.8% of the population of India practice Hinduism. Islam (14.2%), Christianity (2.3%), Sikhism (1.7%), Buddhism (0.7%) and Jainism (0.4%) are the other major religions followed by the people of India.[31] Many tribal religions, such as Sarnaism, are found in India, though these have been affected by major religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity.[32] Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and the Baháʼí Faith are also influential but their numbers are smaller.[32] Atheism and agnostics also have visible influence in India, along with a self-ascribed tolerance to other faiths.[32]

Atheism and agnosticism have a long history in India and flourished within Śramaṇa movement. The Cārvāka school originated in India around the 6th century BCE.[33][34] It is one of the earliest form of materialistic and atheistic movement in ancient India.[35][36] Sramana, Buddhism, Jainism, Ājīvika and some schools of Hinduism consider atheism to be valid and reject the concept of creator deity, ritualism and superstitions.[37][38][39] India has produced some notable atheist politicians and social reformers.[40] According to the 2012 WIN-Gallup Global Index of Religion and Atheism report, 81% of Indians were religious, 13% were not religious, 3% were convinced atheists, and 3% were unsure or did not respond.[41][42]

Philosophy

| |||||

Indian philosophy comprises the philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. There are six schools of orthodox Hindu philosophy—Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā and Vedanta—and four heterodox schools—Jain, Buddhist, Ājīvika and Cārvāka – last two are also schools of Hinduism.[44][45] However, there are other methods of classification; Vidyarania for instance identifies sixteen schools of Indian philosophy by including those that belong to the Śaiva and Raseśvara traditions.[46] Since medieval India (ca.1000–1500), schools of Indian philosophical thought have been classified by the Brahmanical tradition[47][48] as either orthodox or non-orthodox – āstika or nāstika – depending on whether they regard the Vedas as an infallible source of knowledge.[42]

The main schools of Indian philosophy were formalized chiefly between 1000 BCE to the early centuries of the Common Era. According to philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the earliest of these, which date back to the composition of the Upanishads in the later Vedic period (1000–500 BCE), constitute "the earliest philosophical compositions of the world."[49] Competition and integration between the various schools were intense during their formative years, especially between 800 BCE and 200 CE. Some schools like Jainism, Buddhism, Śaiva, and Advaita Vedanta survived, but others, like Samkhya and Ājīvika, did not; they were either assimilated or became extinct. Subsequent centuries produced commentaries and reformulations continuing up to as late as the 20th century. Authors who gave contemporary meaning to traditional philosophies include Shrimad Rajchandra, Swami Vivekananda, Ram Mohan Roy, and Swami Dayananda Saraswati.[50]

Family structure and marriage

For generations, India has had a prevailing tradition of the joint family system. It is when extended members of a family – parents, children, the children's spouses, and their offspring, etc. – live together. Usually, the oldest male member is the head of the joint Indian family system. He mostly makes all important decisions and rules, and other family members are likely to abide by them. With the current economy, lifestyle, and cost of living in most of the metro cities are high, the population is leaving behind the joint family model and adapting to the nuclear family model. Earlier living in a joint family was with the purpose of creating love and concern for the family members. However, now it's a challenge to give time to each other as most of them are out for survival needs.[51] Rise in the trends of nuclear family settings has led to a change in the traditional family headship structure and older males are no longer the mandated heads of the family owing to the fact that they mostly live alone during old age and are far more vulnerable than before.[52]

In a 1966 study, Orenstein and Micklin analysed India's population data and family structure. Their studies suggest that Indian household sizes had remained similar over the 1911 to 1951 period. Thereafter, with urbanisation and economic development, India has witnessed a break up of traditional joint family into more nuclear-like families.[53][54] Sinha, in his book, after summarising the numerous sociological studies done on the Indian family, notes that over the last 60 years, the cultural trend in most parts of India has been an accelerated change from joint family to nuclear families, much like population trends in other parts of the world. The traditionally large joint family in India, in the 1990s, accounted for a small percent of Indian households, and on average had lower per capita household income. He finds that joint family still persists in some areas and in certain conditions, in part due to cultural traditions and in part due to practical factors.[53] Youth in lower socio-economic classes are more inclined to spend time with their families than their peers due to differing ideologies in rural and urban parenting.[55] With the spread of education and growth of economics, the traditional joint-family system is breaking down rapidly across India and attitudes towards working women have changed.

Arranged marriage

|

|

Arranged marriages have long been the norm in Indian society. Even today, the majority of Indians have their marriages planned by their parents and other respected family members. In the past, the age of marriage was young.[56] The average age of marriage for women in India has increased to 21 years, according to the 2011 Census of India.[57] In 2009, about 7% of women got married before the age of 18.[58]

In most marriages, the bride's family provides a dowry to the bridegroom. Traditionally, the dowry was considered a woman's share of the family wealth, since a daughter had no legal claim on her natal family's real estate. It also typically included portable valuables such as jewelry and household goods that a bride could control throughout her life.[59] Historically, in most families the inheritance of family estates passed down the male line. Since 1956, Indian laws treat males and females as equal in matters of inheritance without a legal will.[60] Indians are increasingly using a legal will for inheritance and property succession, with about 20 percent using a legal will by 2004.[61]

In India, the divorce rate is low — 1% compared with about 40% in the United States.[62][63] These statistics do not reflect a complete picture, though. There is a dearth of scientific surveys or studies on Indian marriages where the perspectives of both husbands and wives were solicited in-depth. Sample surveys suggest the issues with marriages in India are similar to trends observed elsewhere in the world. The divorce rates are rising in India. Urban divorce rates are much higher. Women initiate about 80 percent of divorces in India.[64]

Opinion is divided over what the phenomenon means: for traditionalists, the rising numbers portend the breakdown of society while, for some modernists, they speak of healthy new empowerment for women.[65]

Recent studies suggest that Indian culture is trending away from traditional arranged marriages. Banerjee et al. surveyed 41,554 households across 33 states and union territories in India in 2005. They find that the marriage trends in India are similar to trends observed over the last 40 years in China, Japan, and other nations.[66] The study found that fewer marriages are purely arranged without consent and that the majority of surveyed Indian marriages are arranged with consent. The percentage of self-arranged marriages (called love marriages in India) was also increasing, particularly in the urban parts of India.[67]

Wedding rituals

Weddings are festive occasions in India with extensive decorations, colors, music, dance, costumes and rituals that depend on the religion of the bride and the groom, as well as their preferences.[68] The nation celebrates about 10 million weddings per year,[69] of which over 80% are Hindu weddings.

While there are many festival-related rituals in Hinduism, vivaha (wedding) is the most extensive personal ritual an adult Hindu undertakes in his or her life.[70][71] Typical Hindu families spend significant effort and financial resources to prepare and celebrate weddings. The rituals and processes of a Hindu wedding vary depending on the region of India, local adaptations, family resources and preferences of the bride and the groom. Nevertheless, there are a few key rituals common in Hindu weddings – Kanyadaan, Panigrahana, and Saptapadi; these are respectively, gifting away of daughter by the father, voluntarily holding hand near the fire to signify impending union, and taking seven circles before firing with each circle including a set of mutual vows. Mangalsutra necklace of bond a Hindu groom ties with three knots around the bride's neck in a marriage ceremony. The practice is integral to a marriage ceremony as prescribed in Manusmriti, the traditional law governing Hindu marriage. After the seventh circle and vows of Saptapadi, the couple is legally husband and wife.[71][72][73] Sikhs get married through a ceremony called Anand Karaj. The couple walks around the holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib four times. Indian Muslims celebrate a traditional Islamic wedding following customs similar to those practiced in the Middle East. The rituals include Nikah, payment of financial dower called Mahr by the groom to the bride, signing of a marriage contract, and a reception.[74] Indian Christian weddings follow customs similar to those practiced in the Christian countries in the West in states like Goa but have more Indian customs in other states.

Festivals

Procession of the famous “Lalbaug cha Raja” Ganesha idol during the Ganesh Chaturthi festival in Mumbai, Maharashtra

Procession of the famous “Lalbaug cha Raja” Ganesha idol during the Ganesh Chaturthi festival in Mumbai, Maharashtra Vallamkali snakeboat races are a part of Onam festival tradition.

Vallamkali snakeboat races are a part of Onam festival tradition. Dahi Handi, a Krishna Janmashtami festive tradition, in progress near Adi Shankaracharya Road, Mumbai, India

Dahi Handi, a Krishna Janmashtami festive tradition, in progress near Adi Shankaracharya Road, Mumbai, India Durga Puja is a multi-day festival in Eastern India that features elaborate temple and stage decorations (pandals), scripture recitation, performance arts, revelry, and processions.[76]

Durga Puja is a multi-day festival in Eastern India that features elaborate temple and stage decorations (pandals), scripture recitation, performance arts, revelry, and processions.[76] The Hornbill Festival, Kohima, Nagaland. The festival involves colourful performances, crafts, sports, food fairs, games and ceremonies.[77]

The Hornbill Festival, Kohima, Nagaland. The festival involves colourful performances, crafts, sports, food fairs, games and ceremonies.[77]

Rath Yatra celebration a major festival in Puri.

Rath Yatra celebration a major festival in Puri. Carnival in Goa or Viva Carnival is a Celebration prior to fasting season of Lent. It refers to the festival of carnival, or Mardi Gras, in the Indian state of Goa.

Carnival in Goa or Viva Carnival is a Celebration prior to fasting season of Lent. It refers to the festival of carnival, or Mardi Gras, in the Indian state of Goa. Gommateshwara statue during the Grand Consecration Mahamastakabhisheka in August 2018 at Shravanabelagola, Karnataka. Mahamastakabhisheka is held every 12 years and it is considered Jainism's one of the most auspicious festival or celebration.

Gommateshwara statue during the Grand Consecration Mahamastakabhisheka in August 2018 at Shravanabelagola, Karnataka. Mahamastakabhisheka is held every 12 years and it is considered Jainism's one of the most auspicious festival or celebration.

India, being a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-religious society, celebrates holidays and festivals of various religions. The three national holidays in India, the Independence Day, the Republic Day and the Gandhi Jayanti, are celebrated with zeal and enthusiasm across India. In addition, many Indian states and regions have local festivals depending on prevalent religious and linguistic demographics. Popular religious festivals include the Hindu festivals of Navratri, Janmashtami, Diwali, Maha Shivratri, Ganesh Chaturthi, Durga Puja, Holi, Rath Yatra, Ugadi, Vasant Panchami, Rakshabandhan, and Dussehra. Several harvest festivals such as Makar Sankranti, Sohrai, Pusnâ, Hornbill, Chapchar Kut, Pongal, Onam and Raja sankaranti swinging festival are also fairly popular.

India celebrates a variety of festivals due to the large diversity of India. Many religious festivals like Diwali (Hindu) Eid (Muslim) Christmas (Christian), etc. are celebrated by all. The government also provides facilities for the celebration of all religious festivals with equality and grants road bookings, security, etc. providing equality to the diverse religions and their festivals.

The Indian New Year festival is celebrated in different parts of India with a unique style at different times. Ugadi, Bihu, Gudhi Padwa, Puthandu, Vaisakhi, Pohela Boishakh, Vishu and Vishuva Sankranti are the New Year festival of different part of India.

Certain festivals in India are celebrated by multiple religions. Notable examples include Diwali, which is celebrated by Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains across the country and Buddha Purnima, Krishna Janmashtami, Ambedkar Jayanti celebrated by Buddhists and Hindus. Sikh festivals, such as Guru Nanak Jayanti, Baisakhi are celebrated with full fanfare by Sikhs and Hindus of Punjab and Delhi where the two communities together form an overwhelming majority of the population. Adding colours to the culture of India, the Dree Festival is one of the tribal festivals of India celebrated by the Apatanis of the Ziro valley of Arunachal Pradesh, which is the easternmost state of India. Nowruz is the most important festival among the Parsi community of India.

Islam in India is the second largest religion with over 172 million Muslims, according to India's 2011 census.[31] The Islamic festivals which are observed and are declared public holiday in India are; Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha (Bakri Eid), Milad-un-Nabi, Muharram and Shab-e-Barat.[78] Some of the Indian states have declared regional holidays for the particular regional popular festivals; such as Arba'een, Jumu'ah-tul-Wida and Shab-e-Qadar.

Christianity in India is the third-largest religion with over 27.8 million Christians, according to India's 2011 census.[79] With over 27.8 million Christians, of which 17 million are Roman Catholics, India is home to many Christian festivals. The country celebrates Christmas and Good Friday as public holidays.[78]

Regional and community fairs are also a common festivals in India. For example, Pushkar Fair of Rajasthan is one of the world's largest markets of cattle and livestock.

Greetings

Right: Entrance pillar relief (Thrichittatt Maha Vishnu Temple, Kerala, India)

Indian greetings are based on Añjali Mudrā, including Pranāma and Puja.

Greetings include Namaste (Hindi,Sanskrit and Kannada), Nômôskar in Odia, Khulumkha (Tripuri), Namaskar (Marathi), Namaskara (Kannada and Sanskrit), Paranaam (Bhojpuri), Namaskaram (Telugu, Malayalam), Vanakkam (Tamil), Nômôshkar (Bengali), Nomoskar (Assamese), Aadab (Urdu), and Sat Shri Akal (Punjabi). All these are commonly spoken greetings or salutations when people meet and are forms of farewell when they depart. Namaskar is considered slightly more formal than Namaste but both express deep respect. Namaskar is commonly used in India and Nepal by Hindus, Jains and Buddhists, and many continue to use this outside the Indian subcontinent. In Indian and Nepali culture, the word is spoken at the beginning of written or verbal communication. However, the same hands folded gesture may be made wordlessly or said without the folded hand gesture. The word is derived from Sanskrit (Namah): to bow, reverential salutation, and respect, and (te): "to you". Taken literally, it means "I bow to you".[80] In Hinduism it means "I bow to the divine in you."[81][82] In most Indian families, younger men and women are taught to seek the blessing of their elders by reverentially bowing to their elders. This custom is known as Pranāma.

Other greetings include Jai Jagannath (used in Odia) Ami Aschi (used in Bengali), Jai Shri Krishna (in Gujarati and the Braj Bhasha and Rajasthani dialects of Hindi), Ram Ram/(Jai) Sita Ram ji (Awadhi and Bhojpuri dialects of Hindi and other Bihari dialects), and Sat Sri Akal (Punjabi; used by followers of Sikhism), As-salamu alaykum (Urdu; used by follower of Islam), Jai Jinendra (a common greeting used by followers of Jainism), Jai Bhim (used by followers of Ambedkarism), Namo Buddhay (used by followers of Buddhism), Allah Abho (used by followers of the Baháʼí Faith), Shalom aleichem (used by followers of Judaism), Hamazor Hama Ashobed (used by followers of Zoroastrianism), Sahebji (Persian and Gujarati; used by the Parsi people), Dorood (Persian and Gujarati; used by the Irani people), Om Namah Shivaya/Jai Bholenath Jaidev (used in Dogri and Kashmiri, also used in the city of Varanasi), Jai Ambe Maa/Jai Mata di (used in Eastern India), Jai Ganapati Bapa (used in Marathi and Konkani), etc.

These traditional forms of greeting may be absent in the world of business and in India's urban environment, where a handshake is a common form of greeting.[83]

Animals

| |||

The varied and rich wildlife of India has a profound impact on the region's popular culture. Common name for wilderness in India is Jungle which was adopted by Britons living in India to the English language. The word has been also made famous in The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling. India's wildlife has been the subject of numerous other tales and fables such as the Panchatantra and the Jataka tales.[84]

In Hinduism, the cow is regarded as a symbol of ahimsa (non-violence), mother goddess and bringer of good fortune and wealth.[85] For this reason, cows are revered in Hindu culture and feeding a cow is seen as an act of worship. This is why beef remains a taboo food in mainstream Hindu and Jain society.[86]

The Article 48 of the Constitution of India is one of the Directive Principles which directs that the state shall endeavor to prohibit slaughtering and smuggling of cattle, calves and other milch and draught cattle.[87][88] As of January 2012, cow remains a divisive and controversial topic in India. Several states of India have passed laws to protect cows, while many states have no restrictions on the production and consumption of beef. Some groups oppose the butchering of cows, while other secular groups argue that what kind of meat one eats ought to be a matter of personal choice in a democracy. Madhya Pradesh enacted a law in January 2012, namely the Gau-Vansh Vadh Pratishedh (Sanshodhan) Act, which makes cow slaughter a serious offence.[89]

Gujarat, a western state of India, has the Animal Preservation Act, enacted in October 2011, that prohibits the killing of cows along with buying, selling and transport of beef. In contrast, Assam and Andhra Pradesh allow butchering of cattle with a fit-for-slaughter certificate. In the states of West Bengal and Kerala, consumption of beef is not deemed an offence. Contrary to stereotypes, a sizeable number of Hindus eat beef, and many argue that their scriptures, such as Vedic and Upanishadic texts do not prohibit its consumption. In southern Indian state Kerala, for instance, beef accounts for nearly half of all meat consumed by all communities, including Hindus. Sociologists theorise that the widespread consumption of cow meat in India is because it is a far cheaper source of animal protein for the poor than mutton or chicken, which retail at double the price. For these reasons, India's beef consumption post-independence in 1947 has witnessed a much faster growth than any other kind of meat; currently, India is one of the five largest producers and consumers of cattle livestock meat in the world. A beef ban has been made in Maharashtra and other states as of 2015. While states such as Madhya Pradesh are passing local laws to prevent cruelty to cows, other Indians are arguing "If the real objective is to prevent cruelty to animals, then why single out the cows when hundreds of other animals are maltreated?"[90][91][92]

Cuisine

Indian food is as diverse as India. Indian cuisines use numerous ingredients, deploy a wide range of food preparation styles, cooking techniques, and culinary presentations. From salads to sauces, from vegetarian to meat, from spices to sensuous, from bread to desserts, Indian cuisine is invariably complex. Harold McGee, a favourite of many Michelin-starred chefs, writes "for sheer inventiveness with the milk itself as the primary ingredient, no country on earth can match India."[93]

I travel to India at least three to four times a year. It's always inspirational. There is so much to learn from India because each and every state is a country by itself and each has its own cuisine. There are lots of things to learn about the different cuisines – it just amazes me. I keep my mind open and like to explore different places and pick up different influences as I go along. I don't actually think that there is a single state in India that I haven't visited. Indian food is a cosmopolitan cuisine that has so many ingredients. I don't think any cuisine in the world has got so many influences on the way that Indian food has. It is a very rich cuisine and is very varied. Every region in the world has its own sense of how Indian food should be perceived.

... it takes me back to the first Christmas I can remember, when the grandmother I hadn't yet met, who was Indian and lived in England, sent me a box. For me it still carries the taste of strangeness and confusion and wonder.

According to Sanjeev Kapoor, a member of Singapore Airlines' International Culinary Panel, Indian food has long been an expression of world cuisine. Kapoor claims, "if you looked back in India's history and study the food that our ancestors ate, you will notice how much attention was paid to the planning and cooking of a meal. Great thought was given to the texture and taste of each dish."[96] One such historical record is Mānasollāsa, (Sanskrit: मानसोल्लास, The Delight of Mind), written in the 12th century. The book describes the need to change cuisine and food with seasons, various methods of cooking, the best blend of flavours, the feel of various foods, planning and style of dining amongst other things.[97]

India is known for its love of food and spices. Indian cuisine varies from region to region, reflecting the local produce, cultural diversity, and varied demographics of the country. Generally, Indian cuisine can be split into five categories – northern, southern, eastern, western, and northeastern. The diversity of Indian cuisine is characterised by the differing use of many spices and herbs, a wide assortment of recipes and cooking techniques. Though a significant portion of Indian food is vegetarian, many Indian dishes also include meats like chicken, mutton, beef (both cow and buffalo), pork and fish, egg and other seafood. Fish-based cuisines are common in eastern states of India, particularly West Bengal and the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.[98]

Despite this diversity, some unifying threads emerge. Varied uses of spices are an integral part of certain food preparations and are used to enhance the flavour of a dish and create unique flavours and aromas. Cuisine across India has also been influenced by various cultural groups that entered India throughout history, such as the Central Asians, Arabs, Mughals, and European colonists. Sweets are also very popular among Indians, particularly in West Bengal where both Bengali Hindus and Bengali Muslims distribute sweets to mark joyous occasions.

Indian cuisine is one of the most popular cuisines across the globe.[100] In most Indian restaurants outside India, the menu does not do justice to the enormous variety of Indian cuisine available – the most common cuisine served on the menu would be Punjabi cuisine (chicken tikka masala is a very popular dish in the United Kingdom). There do exist some restaurants serving cuisines from other regions of India, although these are few and far between. Historically, Indian spices and herbs were one of the most sought after trade commodities. The spice trade between India and Europe led to the rise and dominance of Arab traders to such an extent that European explorers, such as Vasco da Gama and Christopher Columbus, set out to find new trade routes with India leading to the Age of Discovery.[101] The popularity of curry, which originated in India, across Asia has often led to the dish being labeled as the "pan-Asian" dish.[102]

Regional Indian cuisine continues to evolve. A fusion of East Asian and Western cooking methods with traditional cuisines, along with regional adaptations of fast food are prominent in major Indian cities.[103]

The cuisine of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana consists of the Telugu cuisine, of the Telugu people as well as Hyderabadi cuisine (also known as Nizami cuisine), of the Hyderabadi Muslim community.[104][105] Hyderabadi food is based heavily on non-vegetarian ingredients while, Telugu food is a mix of both vegetarian and non-vegetarian ingredients. Telugu food is rich in spices and chillies are abundantly used. The food also generally tends to be more on the tangy side with tamarind and lime juice both used liberally as souring agents. Rice is the staple food of Telugu people. Starch is consumed with a variety of curries and lentil soups or broths.[106][107] Vegetarian and non-vegetarian foods are both popular. Hyderabadi cuisine includes popular delicacies such as Biryani, Haleem, Baghara baingan and Kheema, while Hyderabadi day to day dishes see some commonalities with Telanganite Telugu food, with its use of tamarind, rice, and lentils, along with meat.[106] Yogurt is a common addition to meals, as a way of tempering spiciness.[108]

Clothing

Traditional clothing in India greatly varies across different parts of the country and is influenced by local culture, geography, climate, and rural/urban settings. Popular styles of dress include draped garments such as sari and mekhela sador for women and dhoti or lungi or panche (in Kannada) for men. Stitched clothes are also popular such as churidar or salwar-kameez for women, with dupatta (long scarf) thrown over shoulder completing the outfit. The salwar is often loose fitting, while churidar is a tighter cut.[109] The dastar, a headgear worn by Sikhs is common in Punjab.

Indian women perfect their sense of charm and fashion with makeup and ornaments. Bindi, mehendi, earrings, bangles and other jewelry are common. On special occasions, such as marriage ceremonies and festivals, women may wear cheerful colours with various ornaments made with gold, silver or other regional stones and gems. Bindi is often an essential part of a Hindu woman's make up. Worn on their forehead, some consider the bindi as an auspicious mark. Traditionally, the red bindi was worn only by married Hindu women, and coloured bindi was worn by single women, but now all colours and glitter have become a part of women's fashion. Some women wear sindoor – a traditional red or orange-red powder (vermilion) in the parting of their hair (locally called mang). Sindoor is the traditional mark of a married woman for Hindus. Single Hindu women do not wear sindoor; neither do over 1 million Indian women from religions other than Hindu and agnostics/atheists who may be married.[109] The make up and clothing styles differ regionally between the Hindu groups, and also by climate or religion, with Christians preferring Western and Muslim preferring the Arabic styles.[110] For men, stitched versions include kurta-pyjama and European-style trousers and shirts. In urban and semi-urban centres, men and women of all religious backgrounds, can often be seen in jeans, trousers, shirts, suits, kurtas and variety of other fashions.[111]

The Didarganj Yakshi (3rd century BCE) depicting the dhoti wrap

The Didarganj Yakshi (3rd century BCE) depicting the dhoti wrap Achkan sherwani and churidar (lower body) worn by Arvind Singh Mewar and his kin during a Hindu wedding in Rajasthan, India

Achkan sherwani and churidar (lower body) worn by Arvind Singh Mewar and his kin during a Hindu wedding in Rajasthan, India.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Indian actress Shriya Saran in woman's kameez with dupatta draped over the neck and decorative bindi on the centre of her forehead

Indian actress Shriya Saran in woman's kameez with dupatta draped over the neck and decorative bindi on the centre of her forehead

J. L. Nehru wearing Nehru jacket and Chooridar.

J. L. Nehru wearing Nehru jacket and Chooridar. Maharani Gayatri Devi, in Nivi sari. The Nivi style drape was created during the colonial era of Indian history in order to create a fashion style which would conform to the Victorian-era sensibilities

Maharani Gayatri Devi, in Nivi sari. The Nivi style drape was created during the colonial era of Indian history in order to create a fashion style which would conform to the Victorian-era sensibilities

Languages and literature

History

|

|

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit ...

— Sir William Jones, 1786[113]

The Rigvedic Sanskrit is one of the oldest attestations of any Indo-Aryan languages, and one of the earliest attested members of the Indo-European languages. The discovery of Sanskrit by early European explorers of India led to the development of comparative Philology. The scholars of the 18th century were struck by the far-reaching similarity of Sanskrit, both in grammar and vocabulary, to the classical languages of Europe. Intensive scientific studies that followed have established that Sanskrit and many Indian derivative languages belong to the family which includes English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Celtic, Greek, Baltic, Armenian, Persian, Tocharian, and other Indo-European languages.[114]

Tamil, one of India's major classical language, descends from Proto-Dravidian languages spoken around the third millennium BCE in peninsular India. The earliest inscriptions of Tamil have been found on pottery dating back to 500 BC. Tamil literature has existed for over two thousand years[115] and the earliest epigraphic records found date from around the 3rd century BCE.[116]

The evolution of language within India may be distinguished over three periods: old, middle and modern Indo-Aryan. The classical form of old Indo-Aryan was Sanskrit meaning polished, cultivated and correct, in distinction to Prakrit – the practical language of the migrating masses evolving without concern to proper pronunciation or grammar, the structure of language changing as those masses mingled, settled new lands and adopted words from people of other native languages. Prakrita became middle Indo-Aryan leading to Pali (the language of early Buddhists and Ashoka era in 200–300 BCE), Prakrit (the language of Jain philosophers) and Apabhramsa (the language blend at the final stage of middle Indo-Aryan). It is Apabhramsa, scholars claim,[114] that flowered into Hindi, Gujarati, Bengali, Marathi, Punjabi, and many other languages now in use in India's north, east and west. All of these Indian languages have roots and structures similar to Sanskrit, to each other and to other Indo-European languages. Thus we have in India three thousand years of continuous linguistic history recorded and preserved in literary documents. This enables scholars to follow language evolution and observe how, by changes hardly noticeable from generation to generation, an original language alters into descendant languages that are now barely recognisable as the same.[114]

_Bandanna_Sweet_Pink.jpg.webp)    |

Sanskrit has had a profound impact on the languages and literature of India. Hindi, India's most spoken language, is a "Sanskritised register" of the Delhi dialect. In addition, all modern Indo-Aryan languages, Munda languages and Dravidian languages, have borrowed many words either directly from Sanskrit (tatsama words), or indirectly via middle Indo-Aryan languages (tadbhava words).[119] Words originating in Sanskrit are estimated to constitute roughly fifty percent of the vocabulary of modern Indo-Aryan languages,[120] and the literary forms of (Dravidian) Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada. Tamil, although to a slightly smaller extent, has also been significantly influenced by Sanskrit.[119] Part of the Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, the Bengali language arose from the eastern Middle Indic languages and its roots are traced to the 5th-century BCE Ardhamagadhi language.[121][122]

Another major Classical Dravidian language, Kannada is attested epigraphically from the mid-1st millennium AD, and literary Old Kannada flourished in the 9th- to 10th-century Rashtrakuta Dynasty. Pre-old Kannada (or Purava Hazhe-Gannada) was the language of Banavasi in the early Common Era, the Satavahana and Kadamba periods and hence has a history of over 2000 years.[123][124][125][126] The Ashoka rock edict found at Brahmagiri (dated 230 BCE) has been suggested to contain a word in identifiable Kannada.[127] Odia is India's 6th classical language in addition to Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam.[128] It is also one of the 22 official languages in the 8th schedule of Indian constitution. Odia's importance to Indian culture, from ancient times, is evidenced by its presence in Ashoka's Rock Edict X, dated to the 2nd century BC.[129][130]

The language with the largest number of speakers in India is Hindi and its various dialects. Early forms of present-day Hindustani developed from the Middle Indo-Aryan apabhraṃśa vernaculars of present-day North India in the 7th–13th centuries. During the time of Islamic rule in parts of India, it became influenced by Persian.[131] The Persian influence led to the development of Urdu, which is more Persianized and written in the Perso-Arabic script. Modern standard Hindi has a lesser Persian influence and is written in the Devanagari script.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Indian English literature developed during the British Raj, pioneered by Rabindranath Tagore, Mulk Raj Anand and Munshi Premchand.[132]

In addition to Indo-European and Dravidian languages, Austro-Asiatic and Tibeto-Burman languages are in use in India.[133][134] The 2011 Linguistic Survey of India states that India has over 780 languages and 66 different scripts, with its state of Arunachal Pradesh with 90 languages.[135]

Epics

The Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa are the oldest preserved and well-known epics of India. Versions have been adopted as the epics of Southeast Asian countries like Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. The Ramayana consists of 24,000 verses in seven books (kāṇḍas) and 500 cantos (sargas),[136] and tells the story of Rama (an incarnation or Avatar of the Hindu preserver-god Vishnu), whose wife Sita is abducted by the demon king of Lanka, Ravana. This epic played a pivotal role in establishing the role of dhárma as a principal ideal guiding force for Hindu way of life.[137] The earliest parts of the Mahabharata text date to 400 BC[138] and is estimated to have reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century AD).[139] Other regional variations of these, as well as unrelated epics include the Tamil Ramavataram, Assamese Saptakanda Ramayana, Kannada Pampa Bharata, Hindi Ramacharitamanasa, and Malayalam Adhyathmaramayanam. In addition to these two great Indian epics, there are The Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature composed in classical Tamil language — Manimegalai, Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi, Silappadikaram, Valayapathi and Kundalakesi.

A manuscript illustration of the Battle of Kurukshetra, fought between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, recorded in the Mahābhārata

A manuscript illustration of the Battle of Kurukshetra, fought between the Kauravas and the Pandavas, recorded in the Mahābhārata The Battle at Lanka, Ramayana by Sahibdin. It depicts the monkey army of the protagonist Rama (top left, blue figure) fighting Ravana—the demon-king of the Lanka—to save Rama's kidnapped wife, Sita. The painting depicts multiple events in the battle against the three-headed demon general Trisiras, in the bottom left. Trisiras is beheaded by Hanuman, the monkey-companion of Rama.

The Battle at Lanka, Ramayana by Sahibdin. It depicts the monkey army of the protagonist Rama (top left, blue figure) fighting Ravana—the demon-king of the Lanka—to save Rama's kidnapped wife, Sita. The painting depicts multiple events in the battle against the three-headed demon general Trisiras, in the bottom left. Trisiras is beheaded by Hanuman, the monkey-companion of Rama. Rama and Hanuman fighting Ravana from Ramavataram, an album painting on paper from Tamil Nadu, c. 1820 CE

Rama and Hanuman fighting Ravana from Ramavataram, an album painting on paper from Tamil Nadu, c. 1820 CE Ilango Adigal is the author of Silappatikaram, one of the five great epics of Tamil literature.[140]

Ilango Adigal is the author of Silappatikaram, one of the five great epics of Tamil literature.[140]

Performing arts

Dance

Let drama and dance (Nātya, नाट्य) be the fifth vedic scripture. Combined with an epic story, tending to virtue, wealth, joy and spiritual freedom, it must contain the significance of every scripture, and forward every art.

India has had a long romance with the art of dance. The Hindu Sanskrit texts Natya Shastra (Science of Dance) and Abhinaya Darpana (Mirror of Gesture) are estimated to be from 200 BCE to early centuries of the 1st millennium CE.[142][143][144]

The Indian art of dance as taught in these ancient books, according to Ragini Devi, is the expression of inner beauty and the divine in man.[145] It is a deliberate art, nothing is left to chance, each gesture seeks to communicate the ideas, each facial expression the emotions.

Indian dance includes eight classical dance forms, many in narrative forms with mythological elements. The eight classical forms accorded classical dance status by India's National Academy of Music, Dance, and Drama are: bharatanatyam of the state of Tamil Nadu, kathak of Uttar Pradesh, kathakali and mohiniattam of Kerala, kuchipudi of Andhra Pradesh, yakshagana of Karnataka, manipuri of Manipur, odissi (orissi) of the state of Odisha and the sattriya of Assam.[146][147]

In addition to the formal arts of dance, Indian regions have a strong free form, folksy dance tradition. Some of the folk dances include the bhangra of Punjab; the bihu of Assam; the zeliang of Nagaland; the Jhumair, Domkach, chhau of Jharkhand; the Ghumura Dance, Gotipua, Mahari dance and Dalkhai of Odisha; the qauwwalis, birhas and charkulas of Uttar Pradesh; the jat-jatin, nat-natin and saturi of Bihar; the ghoomar of Rajasthan and Haryana; the dandiya and garba of Gujarat; the kolattam of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana; the yakshagana of Karnataka; lavani of Maharashtra; Dekhnni of Goa. Recent developments include adoption of international dance forms particularly in the urban centres of India, and the extension of Indian classical dance arts by the Kerala Christian community, to tell stories from the Bible.[148]

Drama

Kathakali one of the classical theatre forms from Kerala, India

Kathakali one of the classical theatre forms from Kerala, India Rasa lila theatrical performance in Manipuri dance style

Rasa lila theatrical performance in Manipuri dance style

A street play (nukkad natak) in Dharavi slums in Mumbai.

A street play (nukkad natak) in Dharavi slums in Mumbai. Yakshagana An Ancient dance drama of Tulunadu.

Yakshagana An Ancient dance drama of Tulunadu. Koodiyattam performer Kapila Venu

Koodiyattam performer Kapila Venu

Indian drama and theatre has a long history alongside its music and dance. Kalidasa's plays like Shakuntala and Meghadoota are some of the older dramas, following those of Bhasa. Kutiyattam of Kerala, is the only surviving specimen of the ancient Sanskrit theatre, thought to have originated around the beginning of the Common Era, and is officially recognised by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. It strictly follows the Natya Shastra.[149] Nātyāchārya Māni Mādhava Chākyār is credited for reviving the age old drama tradition from extinction. He was known for mastery of Rasa Abhinaya. He started to perform the Kalidasa plays like Abhijñānaśākuntala, Vikramorvaśīya and Mālavikāgnimitra; Bhasa's Swapnavāsavadatta and Pancharātra; Harsha's Nagananda.[150][151]

Puppetry

India has a long tradition of puppetry. In the ancient Indian epic Mahabharata there are references to puppets. Kathputli, a form of string puppet performance native to Rajasthan, is notable and there are many Indian ventriloquists and puppeteers. The first Indian ventriloquist, Professor Y. K. Padhye, introduced this form of puppetry to India in the 1920s and his son, Ramdas Padhye, subsequently popularised ventriloquism and puppetry. Ramdas Padhye's son, Satyajit Padhye is also a ventriloquist and puppeteer. Almost all types of puppets are found in India.

- String puppets

_at_Raja_Dinkar_Kelkar_Museum%252C_Pune.JPG.webp)

India has a rich and ancient tradition of string puppets or marionettes. Marionettes with jointed limbs controlled by strings allow far greater flexibility and are therefore the most articulate of the puppets. Rajasthan, Orissa, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu are some of the regions where this form of puppetry has flourished. The traditional marionettes of Rajasthan are known as Kathputli. Carved from a single piece of wood, these puppets are like large dolls that are colourfully dressed. The string puppets of Orissa are known as Kundhei. The string puppets of Karnataka are called Gombeyatta. Puppets from Tamil Nadu, known as Bommalattam, combine the techniques of rod and string puppets.

- Rod puppets

Rod puppets are an extension of glove-puppets, but are often much larger and supported and manipulated by rods from below. This form of puppetry now is found mostly in West Bengal and Orissa. The traditional rod puppet form of West Bengal is known as Putul Nautch. They are carved from wood and follow the various artistic styles of a particular region. The traditional rod puppet of Bihar is known as Yampuri.

- Glove puppets

Glove puppets are also known as sleeve, hand or palm puppets. The head is made of either papier mâché, cloth or wood, with two hands emerging from just below the neck. The rest of the figure consists of a long, flowing skirt. These puppets are like limp dolls, but in the hands of an able puppeteer, are capable of producing a wide range of movements. The manipulation technique is simple the movements are controlled by the human hand, the first finger inserted in the head and the middle finger and the thumb in the two arms of the puppet. With the help of these three fingers, the glove puppet comes alive.

The tradition of glove puppets in India is popular in Uttar Pradesh, Orissa, West Bengal and Kerala. In Uttar Pradesh, glove puppet plays usually present social themes, whereas in Orissa such plays are based on stories of Radha and Krishna. In Orissa, the puppeteer plays a dholak (hand drum) with one hand and manipulates the puppet with the other. The delivery of the dialogue, the movement of the puppet and the beat of the dholak are well synchronised and create a dramatic atmosphere. In Kerala, the traditional glove puppet play is called Pavakoothu.

Shadow play

Shadow puppets are an ancient part of India's culture and art, particularly regionally as the keelu bomme and Tholu bommalata of Andhra Pradesh, the Togalu gombeyaata in Karnataka, the charma bahuli natya in Maharashtra, the Ravana chhaya in Odisha, the Tholpavakoothu in Kerala and the thol bommalatta in Tamil Nadu. Shadow puppet play is also found in pictorial traditions in India, such as temple mural painting, loose-leaf folio paintings, and the narrative paintings.[152] Dance forms such as the Chhau of Odisha literally mean "shadow".[153] The shadow theatre dance drama theatre are usually performed on platform stages attached to Hindu temples, and in some regions these are called Koothu Madams or Koothambalams.[154] In many regions, the puppet drama play is performed by itinerant artist families on temporary stages during major temple festivals.[155] Legends from the Hindu epics Ramayana and the Mahabharata dominate their repertoire.[155] However, the details and the stories vary regionally.[156][157]

During the 19th century and early parts of the 20th century of the colonial era, Indologists believed that shadow puppet plays had become extinct in India, though mentioned in its ancient Sanskrit texts.[155] In the 1930s and thereafter, states Stuart Blackburn, these fears of its extinction were found to be false as evidence emerged that shadow puppetry had remained a vigorous rural tradition in central Kerala mountains, most of Karnataka, northern Andhra Pradesh, parts of Tamil Nadu, Odisha and southern Maharashtra.[155] The Marathi people, particularly of low caste, had preserved and vigorously performed the legends of Hindu epics as a folk tradition. The importance of Marathi artists is evidenced, states Blackburn, from the puppeteers speaking Marathi as their mother tongue in many non-Marathi speaking states of India.[155]

According to Beth Osnes, the tholu bommalata shadow puppet theatre dates back to the 3rd century BCE, and has attracted patronage ever since.[158] The puppets used in a tholu bommalata performance, states Phyllis Dircks, are "translucent, lusciously multicolored leather figures four to five feet tall, and feature one or two articulated arms".[159] The process of making the puppets is an elaborate ritual, where the artist families in India pray, go into seclusion, produce the required art work, then celebrate the "metaphorical birth of a puppet" with flowers and incense.[160]

The tholu pava koothu of Kerala uses leather puppets whose images are projected on a backlit screen. The shadows are used to creatively express characters and stories in the Ramayana. A complete performance of the epic can take forty-one nights, while an abridged performance lasts as few as seven days.[161] One feature of the tholu pava koothu show is that it is a team performance of puppeteers, while other shadow plays such as the wayang of Indonesia are performed by a single puppeteer for the same Ramayana story.[161] There are regional differences within India in the puppet arts. For example, women play a major role in shadow play theatre in most parts of India, except in Kerala and Maharashtra.[155] Almost everywhere, except Odisha, the puppets are made from tanned deer skin, painted and articulated. Translucent leather puppets are typical in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, while opaque puppets are typical in Kerala and Odisha. The artist troupes typically carry over a hundred puppets for their performance in rural India.[155]

Music

Music is an integral part of India's culture. Natyasastra, a 2000-year-old Sanskrit text, describes five systems of taxonomy to classify musical instruments.[164] One of these ancient Indian systems classifies musical instruments into four groups according to four primary sources of vibration: strings, membranes, cymbals, and air. According to Reis Flora, this is similar to the Western theory of organology. Archeologists have also reported the discovery of a 3000-year-old, 20-key, carefully shaped polished basalt lithophone in the highlands of Odisha.[165]

The oldest preserved examples of Indian music are the melodies of the Samaveda (1000 BC) that are still sung in certain Vedic Śrauta sacrifices; this is the earliest account of Indian musical hymns.[166] It proposed a tonal structure consisting of seven notes, which were named, in descending order, as Krusht, Pratham, Dwitiya, Tritiya, Chaturth, Mandra and Atiswār. These refer to the notes of a flute, which was the only fixed frequency instrument. The Samaveda, and other Hindu texts, heavily influenced India's classical music tradition, which is known today in two distinct styles: Carnatic and Hindustani music. Both the Carnatic music and Hindustani music systems are based on the melodic base (known as Rāga), sung to a rhythmic cycle (known as Tāla); these principles were refined in the nātyaśāstra (200 BC) and the dattilam (300 AD).[167]

The current music of India includes multiple varieties of religious, classical, folk, filmi, rock and pop music and dance. The appeal of traditional classical music and dance is on the rapid decline, especially among the younger generation.

Prominent contemporary Indian musical forms included filmi and Indipop. Filmi refers to the wide range of music written and performed for mainstream Indian cinema, primarily Bollywood, and accounts for more than 70 percent of all music sales in the country.[168] Indipop is one of the most popular contemporary styles of Indian music which is either a fusion of Indian folk, classical or Sufi music with Western musical traditions.[169]

Visual arts

Painting

A Prehistoric cave painting in Bhimbetka rock shelters.

A Prehistoric cave painting in Bhimbetka rock shelters. The Jataka tales from Ajanta Caves

The Jataka tales from Ajanta Caves_001.jpg.webp)

Hindu iconography shown in Pattachitra

Hindu iconography shown in Pattachitra Raja Ravi Varma's Shakuntala (1870); oil on canvas

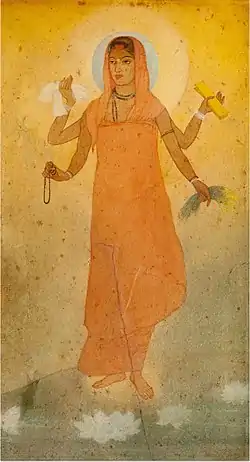

Raja Ravi Varma's Shakuntala (1870); oil on canvas Bharat Mata by Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951), a nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore, and a pioneer of the Bengal School of Art

Bharat Mata by Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951), a nephew of the poet Rabindranath Tagore, and a pioneer of the Bengal School of Art

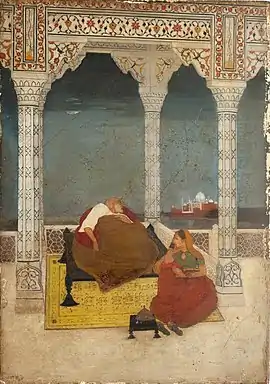

Emperor Jahangir weighs Prince Khurram by Manohar Das, 1610–15, from Jahangir's own copy of the Tuzk-e-Jahangiri. The names of the main figures are noted on their clothes, and the artist shown at bottom.

Emperor Jahangir weighs Prince Khurram by Manohar Das, 1610–15, from Jahangir's own copy of the Tuzk-e-Jahangiri. The names of the main figures are noted on their clothes, and the artist shown at bottom.

Cave paintings from Ajanta, Bagh, Ellora and Sittanavasal and temple paintings testify to a love of naturalism. Most early and medieval art in India is Hindu, Buddhist or Jain. A freshly made coloured floor design (Rangoli) is still a common sight outside the doorstep of many (mostly South Indian) Indian homes. Raja Ravi Varma is one of the classical painters from medieval India.

Pattachitra, Madhubani painting, Mysore painting, Rajput painting, Tanjore painting and Mughal painting are some notable Genres of Indian Art; while Nandalal Bose, M. F. Husain, S. H. Raza, Geeta Vadhera, Jamini Roy and B. Venkatappa[170] are some modern painters. Among the present day artists, Atul Dodiya, Bose Krishnamacnahri, Devajyoti Ray and Shibu Natesan represent a new era of Indian art where global art shows direct amalgamation with Indian classical styles. These recent artists have acquired international recognition. Jehangir Art Gallery in Mumbai, Mysore Palace has on display a few good Indian paintings.

Sculpture

Woman riding two bulls (bronze), from Kausambi, c. 2000-1750 BCE

Woman riding two bulls (bronze), from Kausambi, c. 2000-1750 BCE

5th-century Buddha statue in Kanheri caves, Mumbai

5th-century Buddha statue in Kanheri caves, Mumbai_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Bhutesvara Yakshis, reliefs from Mathura, 2nd century CE

Bhutesvara Yakshis, reliefs from Mathura, 2nd century CE Intricately carved sculptures on the exterior of one of the Khajuraho Group of Monuments

Intricately carved sculptures on the exterior of one of the Khajuraho Group of Monuments

The Thiruvalluvar Statue, or the Valluvar Statue, is a 133-feet (40.6 m) tall stone sculpture of the Tamil poet and philosopher Tiruvalluvar

The Thiruvalluvar Statue, or the Valluvar Statue, is a 133-feet (40.6 m) tall stone sculpture of the Tamil poet and philosopher Tiruvalluvar The Statue of Unity is the world's tallest statue, with a height of 182 metres (597 feet), located in the state of Gujarat.It depicts Indian statesman and independence activist Vallabhbhai Patel (1875–1950), who was the first deputy prime minister and home minister of independent India. It was inaugurated by the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, on 31 October 2018.

The Statue of Unity is the world's tallest statue, with a height of 182 metres (597 feet), located in the state of Gujarat.It depicts Indian statesman and independence activist Vallabhbhai Patel (1875–1950), who was the first deputy prime minister and home minister of independent India. It was inaugurated by the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, on 31 October 2018.

The first sculptures in India date back to the Indus Valley civilisation, where stone and bronze figures have been discovered. Later, as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism developed further, India produced some extremely intricate bronzes as well as temple carvings. Some huge shrines, such as the one at Ellora were not constructed by using blocks but carved out of solid rock.

Sculptures produced in the northwest, in stucco, schist, or clay, display a very strong blend of Indian and Classical Hellenistic or possibly even Greco-Roman influence. The pink sandstone sculptures of Mathura evolved almost simultaneously. During the Gupta period (4th to 6th centuries) sculpture reached a very high standard in execution and delicacy in modeling. These styles and others elsewhere in India evolved leading to classical Indian art that contributed to Buddhist and Hindu sculptures throughout Southeast Central and East Asia.

Architecture

North Gate of Dholavira, an Indus valley civilisation archeological site built around the 3rd Millennium B.C in modern day Gujarat.

North Gate of Dholavira, an Indus valley civilisation archeological site built around the 3rd Millennium B.C in modern day Gujarat. Great Stupa of Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh built in the 3rd century BCE.

Great Stupa of Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh built in the 3rd century BCE. Kailasa temple is one of the largest rock-cut ancient Hindu temples located in Ellora, Maharashtra, India.

Kailasa temple is one of the largest rock-cut ancient Hindu temples located in Ellora, Maharashtra, India. The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.

The granite tower of Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur was completed in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I._(14465165685).jpg.webp) Chennakesava Temple is a model example of the Hoysala architecture.

Chennakesava Temple is a model example of the Hoysala architecture. Chaturbhuj Temple at Orchha, is noted for having one of the tallest Vimana among Hindu temples standing at 344 feet. It was the tallest structure in the Indian subcontinent from 1558 CE to 1970 CE.

Chaturbhuj Temple at Orchha, is noted for having one of the tallest Vimana among Hindu temples standing at 344 feet. It was the tallest structure in the Indian subcontinent from 1558 CE to 1970 CE. The rock-cut Shore Temple of the temples in Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, 700–728. Showing the typical dravida form of tower.

The rock-cut Shore Temple of the temples in Mahabalipuram, Tamil Nadu, 700–728. Showing the typical dravida form of tower. Considered to be an "unrivalled architectural wonder", the Taj Mahal in Agra is a prime example of Indo-Islamic architecture. One of the world's seven wonders.[171]

Considered to be an "unrivalled architectural wonder", the Taj Mahal in Agra is a prime example of Indo-Islamic architecture. One of the world's seven wonders.[171].jpg.webp) Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s and is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Tawang Monastery in Arunachal Pradesh, was built in the 1600s and is the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world after the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet.

Thakur Dalan of Itachuna Rajbari, Khanyan

Thakur Dalan of Itachuna Rajbari, Khanyan

Dravidian style in form of Tamil architecture of Meenakshi Temple

Dravidian style in form of Tamil architecture of Meenakshi Temple The Charminar, built in the 16th century by the Golconda Sultanate.

The Charminar, built in the 16th century by the Golconda Sultanate.

.jpg.webp)

Pachin Kari or Pietra Dura on Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah

Pachin Kari or Pietra Dura on Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah The Stone Chariot in Hampi

The Stone Chariot in Hampi The Viceregal Lodge, now Rashtrapati Niwas, in Shimla designed by Henry Irwin in the Jacobethan style and built in the late 19th century.

The Viceregal Lodge, now Rashtrapati Niwas, in Shimla designed by Henry Irwin in the Jacobethan style and built in the late 19th century. Fort Dansborg, built by the 17th century Danish admiral Ove Gjedde, reminiscences of Danish India, Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu

Fort Dansborg, built by the 17th century Danish admiral Ove Gjedde, reminiscences of Danish India, Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu

Indian architecture encompasses a multitude of expressions over space and time, constantly absorbing new ideas. The result is an evolving range of architectural production that nonetheless retains a certain amount of continuity across history. Some of its earliest production are found in the Indus Valley civilisation (2600–1900 BC) which is characterised by well-planned cities and houses. Religion and kingship do not seem to have played an important role in the planning and layout of these towns.[172]

During the period of the Mauryan and Gupta empires and their successors, several Buddhist architectural complexes, such as the caves of Ajanta and Ellora and the monumental Sanchi Stupa were built. Later on, South India produced several Hindu temples like Chennakesava Temple at Belur, the Hoysaleswara Temple at Halebidu, and the Kesava Temple at Somanathapura, Brihadeeswara Temple, Thanjavur built by Raja Raja Chola, the Sun Temple, Konark, Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple at Srirangam, and the Buddha stupa (Chinna Lanja dibba and Vikramarka kota dibba) at Bhattiprolu. Rajput kingdoms oversaw the construction of Khajuraho Temple Complex, Chittor Fort and Chaturbhuj Temple, etc. during their reign. Angkor Wat, Borobudur and other Buddhist and Hindu temples indicate strong Indian influence on South East Asian architecture, as they are built in styles almost identical to traditional Indian religious buildings.

The traditional system of Vaastu Shastra serves as India's version of Feng Shui, influencing town planning, architecture, and ergonomics. It is unclear which system is older, but they contain certain similarities. Feng Shui is more commonly used throughout the world. Though Vastu is conceptually similar to Feng Shui in that it also tries to harmonise the flow of energy, (also called life-force or Prana in Sanskrit and Chi/Ki in Chinese/Japanese), through the house, it differs in the details, such as the exact directions in which various objects, rooms, materials, etc. are to be placed.

With the advent of Islamic influence from the west, Indian architecture was adapted to allow the traditions of the new religion, creating the Indo-Islamic style of architecture. The Qutb complex, a group of monuments constructed by successive sultanas of the Delhi Sultanate is one of the earliest examples. Fatehpur Sikri,[174] Taj Mahal,[175] Gol Gumbaz, Red Fort of Delhi[176] and Charminar are creations of this era, and are often used as the stereotypical symbols of India.

British colonial rule in India saw the development of Indo-Saracenic style and mixing of several other styles, such as European Gothic. The Victoria Memorial and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus are notable examples.

Indian architecture has influenced eastern and southeastern Asia, due to the spread of Buddhism. A number of Indian architectural features such as the temple mound or stupa, temple spire or shikhara, temple tower or pagoda and temple gate or torana, have become famous symbols of Asian culture, used extensively in East Asia and South East Asia. The central spire is also sometimes called a vimanam. The southern temple gate, or gopuram is noted for its intricacy and majesty.

Contemporary Indian architecture is more cosmopolitan. Cities are extremely compact and densely populated. Mumbai's Nariman Point is famous for its Art Deco buildings. Recent creations such as the Lotus Temple,[177] Golden Pagoda and Akshardham, and the various modern urban developments of India like Bhubaneswar and Chandigarh, are notable.

Sports and martial arts

Sports

|

|

|

Field hockey was considered to be the national game of India, but this has been recently denied by the Government of India, clarifying on a Right to Information Act (RTI) filed that India has not declared any sport as the national game.[178][179][180] At a time when it was especially popular, the India men's national field hockey team won the 1975 Men's Hockey World Cup, and 8 gold, 1 silver, and 2 bronze medals at the Olympic Games. However, field hockey in India no longer has the following that it once did.[180]

Cricket is considered the most popular sport in India.[179] The India national cricket team won the 1983 Cricket World Cup, the 2011 Cricket World Cup, the 2007 ICC World Twenty20, the 2013 ICC Champions Trophy and shared the 2002 ICC Champions Trophy with Sri Lanka. Domestic competitions include the Ranji Trophy, the Duleep Trophy, the Deodhar Trophy, the Irani Trophy and the Challenger Series. In addition, BCCI conducts the Indian Premier League, a Twenty20 competition.

Football is popular in the Indian state of Kerala also considered as home of football in India.The city of Kolkata is the home to the largest stadium in India, and the second largest stadium in the world by capacity, Salt Lake Stadium.National clubs such as Mohun Bagan A.C., Kingfisher East Bengal F.C., Prayag United S.C., and the Mohammedan Sporting Club.[181]

Chess is commonly believed to have originated in northwestern India during the Gupta empire,[182][183][184][185] where its early form in the 6th century was known as chaturanga. Other games which originated in India and continue to remain popular in wide parts of northern India include Kabaddi, Gilli-danda, and Kho kho. Traditional southern Indian games include Snake boat race and Kuttiyum kolum. The modern game of polo is derived from Manipur, India, where the game was known as 'Sagol Kangjei', 'Kanjai-bazee', or 'Pulu'.[186][187] It was the anglicised form of the last, referring to the wooden ball that was used, which was adopted by the sport in its slow spread to the west. The first polo club was established in the town of Silchar in Assam, India, in 1833.

In 2011, India inaugurated a privately built Buddh International Circuit, its first motor racing circuit. The 5.14-kilometre circuit is in Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, near Delhi. The first Formula One Indian Grand Prix event was hosted here in October 2011.[188][189]

Indian martial arts

One of the best known forms of ancient Indian martial arts is the Kalarippayattu from Kerala. This ancient fighting style is mentioned in Sangam literature 400 BCE and 600 CE and is regarded as one of the oldest surviving martial arts.[192][193] In this form of martial arts, various stages of physical training include ayurvedic massage with sesame oil to impart suppleness to the body (uzichil); a series of sharp body movements so as to gain control over various parts of the body (miapayattu); and, complex sword fighting techniques (paliyankam).[194]Silambam, which was developed around 200 AD, traces its roots to the Sangam period in southern India.[195] Silambam is unique among Indian martial arts because it uses complex footwork techniques (kaaladi), including a variety of spinning styles. A bamboo staff is used as the main weapon.[195] The ancient Tamil Sangam literature mentions that between 400 BCE and 600 CE, soldiers from southern India received special martial arts training which revolved primarily around the use of spear (vel), sword (val) and shield (kedaham).[196]

Among eastern states, Paika akhada is a martial art found in Odisha. Paika akhada, or paika akhara, roughly translates as "warrior gymnasium" or "warrior school".[197] In ancient times, these were training schools of the peasant militia. Today's Paika akhada teach physical exercises and martial arts in addition to the Paika dance, performance art with rhythmic movements and weapons being hit in time to the drum. It incorporates acrobatic manoeuvres and use of the khanda (straight sword), patta (guantlet-sword), sticks, and other weapons.

In northern India, the musti yuddha evolved in 1100 AD and focussed on mental, physical and spiritual training.[198] In addition, the Dhanur Veda tradition was an influential fighting arts style which considered the bow and the arrow to be the supreme weapons. The Dhanur Veda was first described in the 5th-century BCE Viṣṇu Purāṇa[193] and is also mentioned in both of the major ancient Indian epics, the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata. A distinctive factor of Indian martial arts is the heavy emphasis laid on meditation (dhyāna) as a tool to remove fear, doubt and anxiety.[199]

Indian martial arts techniques have had a profound impact on other martial arts styles across Asia. The 3rd-century BCE Yoga Sutras of Patanjali taught how to meditate single-mindedly on points located inside one's body, which was later used in martial arts, while various mudra finger movements were taught in Yogacara Buddhism. These elements of yoga, as well as finger movements in the nata dances, were later incorporated into various martial arts.[200] According to some historical accounts, the South Indian Buddhist monk Bodhidharma was one of the main founders of the Shaolin Kungfu.[201]

Popular media

Television

.jpg.webp)

Indian television started off in 1959 in New Delhi with tests for educational telecasts.[202][203] Indian small screen programming started off in the mid-1970s. Only one national channel, the government-owned Doordarshan existed around that time. The year 1982 marked a revolution in TV programming in India, as the New Delhi Asian games became the first to be broadcast on the colour version of TV. The Ramayana and Mahabharat were among the popular television series produced. By the late 1980s television set ownership rapidly increased.[204] Because a single channel was catering to an ever-growing audience, television programming quickly reached saturation. Hence the government started another channel that had part of national programming and part regional. This channel was known as DD 2 (later DD Metro). Both channels were broadcast terrestrially.

In 1991, the government liberated its markets, opening them up to cable television. Since then, there has been a spurt in the number of channels available. Today, the Indian small screen is a huge industry by itself and offers hundreds of programmes in almost all the regional languages of India. The small screen has produced numerous celebrities of their own kind, some even attaining national fame for themselves. TV soaps enjoy popularity among women of all classes. Indian TV also consists of Western channels such as Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon, HBO, and FX. In 2016 the list of TV channels in India stood at 892.[205]

Cinema

|

|

Bollywood is the informal name given to the popular Mumbai-based film industry in India. Bollywood and the other major cinematic hubs (in Bengali Cinema, Oriya film industry, Assamese, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Tamil, Punjabi and Telugu) constitute the broader Indian film industry, whose output is considered to be the largest in the world in terms of number of films produced and number of tickets sold.

India has produced many cinema-makers like S.S.Rajamouli, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, J. C. Daniel, K. Viswanath, Ram Gopal Varma, Bapu, Ritwik Ghatak, Guru Dutt, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shaji N. Karun, Girish Kasaravalli, Shekhar Kapoor, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Nagraj Manjule, Shyam Benegal, Shankar Nag, Girish Karnad, G. V. Iyer, Mani Ratnam, and K. Balachander (see also: Indian film directors). With the opening up of the economy in recent years and consequent exposure to world cinema, audience tastes have been changing. In addition, multiplexes have mushroomed in most cities, changing the revenue patterns.

Perceptions of Indian culture

India's diversity has inspired many writers to pen their perceptions of the country's culture. These writings paint a complex and often conflicting picture of the culture of India. India is one of the most ethnically and religiously diverse countries in the world. The concept of "Indian culture" is a very complex and complicated matter. Indian citizens are divided into various ethnic, religious, caste, linguistic and regional groups, making the realities of "Indianness" extremely complicated. This is why the conception of Indian identity poses certain difficulties and presupposes a series of assumptions about what concisely the expression "Indian" means. However, despite this vast and heterogeneous composition, the creation of some sort of typical or shared Indian culture results from some inherent internal forces (such as a robust Constitution, universal adult franchise, flexible federal structure, secular educational policy, etc.) and from certain historical events (such as Indian Independence Movement, Partition, wars against Pakistan, etc.) Hindu Sanskriti Ankh is an ancient series of books originally from northern part of India highlighting the Bharatiya sanskriti, that is, the culture of India.

According to industry consultant Eugene M. Makar, for example, traditional Indian culture is defined by a relatively strict social hierarchy. He also mentions that from an early age, children are reminded of their roles and places in society.[206] This is reinforced, Makar notes, by the way, many believe gods and spirits have an integral and functional role in determining their life. Several differences such as religion divide the culture. However, a far more powerful division is the traditional Hindu bifurcation into non-polluting and polluting occupations. Strict social taboos have governed these groups for thousands of years, claims Makar. In recent years, particularly in cities, some of these lines have blurred and sometimes even disappeared. He writes important family relations extend as far as 1 gotra, the mainly patrilinear lineage or clan assigned to a Hindu at birth. In rural areas & sometimes in urban areas as well, it is common that three or four generations of the family live under the same roof. The patriarch often resolves family issues.[206]