Erik Satie

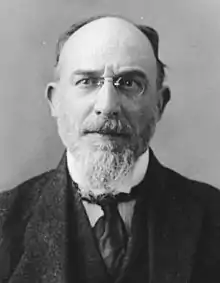

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie (UK: /ˈsæti, ˈsɑːti/, US: /sæˈtiː, sɑːˈtiː/;[1][2] French: [eʁik sati]; 17 May 1866 – 1 July 1925), who signed his name Erik Satie after 1884, was a French composer and pianist. He was the son of a French father and a British mother. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire, but was an undistinguished student and obtained no diploma. In the 1880s he worked as a pianist in café-cabaret in Montmartre, Paris, and began composing works, mostly for solo piano, such as his Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes. He also wrote music for a Rosicrucian sect to which he was briefly attached.

After a spell in which he composed little, Satie entered Paris's second music academy, the Schola Cantorum, as a mature student. His studies there were more successful than those at the Conservatoire. From about 1910 he became the focus of successive groups of young composers attracted by his unconventionality and originality. Among them were the group known as Les Six. A meeting with Jean Cocteau in 1915 led to the creation of the ballet Parade (1917) for Serge Diaghilev, with music by Satie, sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso, and choreography by Léonide Massine.

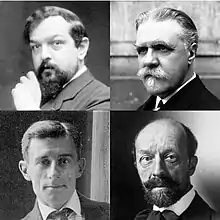

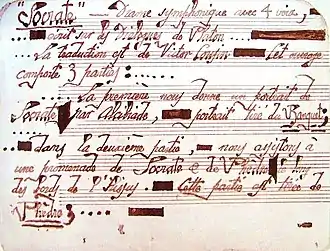

Satie's example guided a new generation of French composers away from post-Wagnerian impressionism towards a sparer, terser style. Among those influenced by him during his lifetime were Maurice Ravel, Claude Debussy, and Francis Poulenc, and he is seen as an influence on more recent, minimalist composers such as John Cage and John Adams. His harmony is often characterised by unresolved chords, he sometimes dispensed with bar-lines, as in his Gnossiennes, and his melodies are generally simple and often reflect his love of old church music. He gave some of his later works absurd titles, such as Veritables Preludes flasques (pour un chien) ("True Flabby Preludes (for a Dog)", 1912), Croquis et agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois ("Sketches and Exasperations of a Big Wooden Man", 1913) and Sonatine bureaucratique ("Bureaucratic Sonatina", 1917). Most of his works are brief, and the majority are for solo piano. Exceptions include his "symphonic drama" Socrate (1919) and two late ballets Mercure and Relâche (1924).

Satie never married, and his home for most of his adult life was a single small room, first in Montmartre and, from 1898 to his death, in Arcueil, a suburb of Paris. He adopted various images over the years, including a period in quasi-priestly dress, another in which he always wore identically coloured velvet suits, and is known for his last persona, in neat bourgeois costume, with bowler hat, wing collar, and umbrella. He was a lifelong heavy drinker, and died of cirrhosis of the liver at the age of 59.

Life and career

Early years

Satie was born on 17 May 1866 in Honfleur, Normandy, the first child of Alfred Satie and his wife Jane Leslie (née Anton). Jane Satie was an English Protestant of Scottish descent; Alfred Satie, a shipping broker, was a Roman Catholic anglophobe.[3] A year later, the Saties had a daughter, Olga, and in 1869 a second son, Conrad. The children were baptised in the Anglican church.[3]

After the Franco-Prussian War, Alfred Satie sold his business and the family moved to Paris, where he eventually set up as a music publisher.[4] In 1872 Jane Satie died and Eric and his brother were sent back to Honfleur to be brought up by Alfred's parents. The boys were rebaptised as Roman Catholics and educated at a local boarding school, where Satie excelled in history and Latin but nothing else.[5] In 1874 he began taking music lessons with a local organist, Gustave Vinot, a former pupil of Louis Niedermeyer. Vinot stimulated Satie's love of old church music, and in particular Gregorian chant.[6]

In 1878 Satie's grandmother died,[n 1] and the two boys returned to Paris to be informally educated by their father. Satie did not attend a school, but his father took him to lectures at the Collège de France and engaged a tutor to teach Eric Latin and Greek. Before the boys returned to Paris from Honfleur, Alfred had met a piano teacher and salon composer, Eugénie Barnetche, whom he married in January 1879, to the dismay of the twelve-year-old Satie, who did not like her.[7]

Eugénie Satie resolved that her elder stepson should become a professional musician, and in November 1879 enrolled him in the preparatory piano class at the Paris Conservatoire.[8] Satie strongly disliked the Conservatoire, which he described as "a vast, very uncomfortable, and rather ugly building; a sort of district prison with no beauty on the inside – nor on the outside, for that matter".[n 2] He studied solfeggio with Albert Lavignac and piano with Émile Decombes, who had been a pupil of Frédéric Chopin.[10] In 1880 Satie took his first examinations as a pianist: he was described as "gifted but indolent". The following year Decombes called him "the laziest student in the Conservatoire".[8] In 1882 he was expelled from the Conservatoire for his unsatisfactory performance.[4]

In 1884 Satie wrote his first known composition, a short Allegro for piano, written while on holiday in Honfleur. He signed himself "Erik" on this and subsequent compositions, though continuing to use "Eric" on other documents until 1906.[11] In 1885, he was readmitted to the Conservatoire, in the intermediate piano class of his stepmother's former teacher, Georges Mathias. He made little progress: Mathias described his playing as "Insignificant and laborious" and Satie himself "Worthless. Three months just to learn the piece. Cannot sight-read properly".[12][n 3] Satie became fascinated by aspects of religion. He spent much time in Notre-Dame de Paris contemplating the stained glass windows and in the National Library examining obscure medieval manuscripts.[15] His friend Alphonse Allais later dubbed him "Esotérik Satie".[16] From this period comes Ogives, a set of four piano pieces inspired by Gregorian chant and Gothic church architecture.[17]

Keen to leave the Conservatoire, Satie volunteered for military service, and joined the 33rd Infantry Regiment in November 1886.[18] He quickly found army life no more to his liking than the Conservatoire, and deliberately contracted acute bronchitis by standing in the open, bare-chested, on a winter night.[19] After three months' convalescence he was invalided out of the army.[8][20]

Montmartre

In 1887, at the age of 21, Satie moved from his father's residence to lodgings in the 9th arrondissement. By this time he had started what was to be an enduring friendship with the romantic poet Contamine de Latour, whose verse he set in some of his early compositions, which Satie senior published.[8] His lodgings were close to the popular Chat Noir cabaret on the southern edge of Montmartre where he became an habitué and then a resident pianist. The Chat Noir was known as the "temple de la 'convention farfelue'" – the temple of zany convention,[21] and as the biographer Robert Orledge puts it, Satie, "free from his restrictive upbringing … enthusiastically embraced the reckless bohemian lifestyle and created for himself a new persona as a long-haired man-about-town in frock coat and top hat". This was the first of several personas that Satie invented for himself over the years.[8]

In the late 1880s Satie styled himself on at least one occasion "Erik Satie – gymnopédiste",[22][n 4] and his works from this period include the three Gymnopédies (1888) and the first Gnossiennes (1889 and 1890). He earned a modest living as pianist and conductor at the Chat Noir, before falling out with the proprietor and moving to become second pianist at the nearby Auberge du Clou. There he became a close friend of Claude Debussy, who proved a kindred spirit in his experimental approach to composition. Both were bohemians, enjoying the same café society and struggling to survive financially.[24] At the Auberge du Clou Satie first encountered the flamboyant, self-styled "Sâr" Joséphin Péladan, for whose mystic sect, the Ordre de la Rose-Croix Catholique du Temple et du Graal, he was appointed composer.[25] This gave him scope for experiment, and Péladan's salons at the fashionable Galerie Durand-Ruel gained Satie his first public hearings.[8][26] Frequently short of money, Satie moved from his lodgings in the 9th arrondissement to a small room in the rue Cortot not far from Sacre-Coeur,[27] so high up the Butte Montmartre that he said he could see from his window all the way to the Belgian border.[n 5]

By mid-1892, Satie had composed the first pieces in a compositional system of his own making (Fête donnée par des Chevaliers Normands en l'honneur d'une jeune demoiselle), provided incidental music to a chivalric esoteric play (two Préludes du Nazaréen), had a hoax published (announcing the premiere of his non-existent Le bâtard de Tristan, an anti-Wagnerian opera),[29] and broken away from Péladan, starting that autumn with the "Uspud" project, a "Christian Ballet", in collaboration with Latour.[30] He challenged the musical establishment by proposing himself – unsuccessfully – for the seat in the Académie des Beaux-Arts made vacant by the death of Ernest Guiraud.[31][n 6] Between 1893 and 1895, Satie, affecting a quasi-priestly dress, was the founder and only member of the Eglise Métropolitaine d'Art de Jésus Conducteur. From his "Abbatiale" in the rue Cortot, he published scathing attacks on his artistic enemies.[8]

In 1893 Satie had what is believed to be his only love affair, a five-month liaison with the painter Suzanne Valadon. After their first night together, he proposed marriage. The two did not marry, but Valadon moved to a room next to Satie's at the rue Cortot. Satie became obsessed with her, calling her his Biqui and writing impassioned notes about "her whole being, lovely eyes, gentle hands, and tiny feet".[33] During their relationship Satie composed the Danses gothiques as a means of calming his mind,[34] and Valadon painted his portrait, which she gave him. After five months she moved away, leaving him devastated. He said later that he was left with "nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness".[33]

In 1895 Satie attempted to change his image once again: this time to that of "the Velvet Gentleman". From the proceeds of a small legacy he bought seven identical dun-coloured suits. Orledge comments that this change "marked the end of his Rose+Croix period and the start of a long search for a new artistic direction".[8]

Move to Arcueil

In 1898, in search of somewhere cheaper and quieter than Montmartre, Satie moved to a room in the southern suburbs, in the commune of Arcueil-Cachan, eight kilometres (five miles) from the centre of Paris.[35][36] This remained his home for the rest of his life. No visitors were ever admitted.[8] He joined a radical socialist party (he later switched his membership to the Communist Party),[37] but adopted a thoroughly bourgeois image: the biographer Pierre-Daniel Templier, writes, "With his umbrella and bowler hat, he resembled a quiet school teacher. Although a Bohemian, he looked very dignified, almost ceremonious".[38]

Satie earned a living as a cabaret pianist, adapting more than a hundred compositions of popular music for piano or piano and voice, adding some of his own. The most popular of these were Je te veux, text by Henry Pacory; Tendrement, text by Vincent Hyspa; Poudre d'or, a waltz; La Diva de l'Empire, text by Dominique Bonnaud/Numa Blès; Le Picadilly, a march; Légende californienne, text by Contamine de Latour (lost, but the music later reappears in La belle excentrique); and others. In his later years Satie rejected all his cabaret music as vile and against his nature.[39] Only a few compositions that he took seriously remain from this period: Jack in the Box, music to a pantomime by Jules Depaquit (called a "clownerie" by Satie); Geneviève de Brabant, a short comic opera to a text by "Lord Cheminot" (Latour); Le poisson rêveur (The Dreamy Fish), piano music to accompany a lost tale by Cheminot, and a few others that were mostly incomplete. Few were presented, and none published at the time.[40]

A decisive change in Satie's musical outlook came after he heard the premiere of Debussy's opera Pelléas et Mélisande in 1902. He found it "absolutely astounding", and he re-evaluated his own music.[8] In a determined attempt to improve his technique, and against Debussy's advice, he enrolled as a mature student at Paris's second main music academy, the Schola Cantorum in October 1905, continuing his studies there until 1912.[41] The institution was run by Vincent d'Indy, who emphasised orthodox technique rather than creative originality.[42] Satie studied counterpoint with Albert Roussel and composition with d'Indy, and was a much more conscientious and successful student than he had been at the Conservatoire in his youth.[43]

It was not until 1911, when he was in his mid-forties, that Satie came to the notice of the musical public in general. In January of that year Maurice Ravel played some early Satie works at a concert by the Société musicale indépendante, a forward-looking group set up by Ravel and others as a rival to the conservative Société nationale de musique.[44][n 7] Satie was suddenly seen as "the precursor and apostle of the musical revolution now taking place";[46] he became a focus for young composers. Debussy, having orchestrated the first and third Gymnopédies, conducted them in concert. The publisher Demets asked for new works from Satie, who was finally able to give up his cabaret work and devote himself to composition. Works such as the cycle Sports et divertissements (1914) were published in de luxe editions. The press began to write about Satie's music, and a leading pianist, Ricardo Viñes, took him up, giving celebrated first performances of some Satie pieces.[8]

Last years

Satie became the focus of successive groups of young composers, whom he first encouraged and then distanced himself from, sometimes rancorously, when their popularity threatened to eclipse his or they otherwise displeased him.[47] First were the "jeunes" – those associated with Ravel – and then a group known at first as the "nouveaux jeunes", later called Les Six, including Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, and Germaine Tailleferre, joined later by Francis Poulenc and Darius Milhaud.[8] Satie dissociated himself from the second group in 1918, and in the 1920s he became the focal point of another set of young composers including Henri Cliquet-Pleyel, Roger Désormière, Maxime Jacob and Henri Sauguet, who became known as the "Arcueil School".[48] In addition to turning against Ravel, Auric and Poulenc in particular,[49] Satie quarrelled with his old friend Debussy in 1917, resentful of the latter's failure to appreciate the more recent Satie compositions.[50] The rupture lasted for the remaining months of Debussy's life, and when he died the following year, Satie refused to attend the funeral.[51] A few of his protégés escaped his displeasure, and Milhaud and Désormière were among those who remained friends with him to the last.[52]

The First World War restricted concert-giving to some extent, but Orledge comments that the war years brought "Satie's second lucky break", when Jean Cocteau heard Viñes and Satie perform the Trois morceaux in 1916. This led to the commissioning of the ballet Parade, premiered in 1917 by Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, with music by Satie, sets and costumes by Pablo Picasso, and choreography by Léonide Massine. This was a succès de scandale, with jazz rhythms and instrumentation including parts for typewriter, steamship whistle and siren. It firmly established Satie's name before the public, and thereafter his career centred on the theatre, writing mainly to commission.[8]

In October 1916 Satie received a commission from the Princesse de Polignac that resulted in what Orledge rates as the composer's masterpiece, Socrate, two years later. Satie set translations from Plato's Dialogues as a "symphonic drama". Its composition was interrupted in 1917 by a libel suit brought against him by a music critic, Jean Poueigh, which nearly resulted in a jail sentence for Satie. When Socrate was premiered, Satie called it "a return to classical simplicity with a modern sensibility", and among those who admired the work was Igor Stravinsky, a composer whom Satie regarded with awe.[8][13]

In his later years Satie became known for his prose. He was in demand as a journalist, making contributions to the Revue musicale, Action, L'Esprit nouveau, the Paris-Journal [53] and other publications from the Dadaist 391[54] to the English-language magazines Vanity Fair and The Transatlantic Review.[8][55] As he contributed anonymously or under pen names to some publications it is not certain how many titles he wrote for, but Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians lists 25.[8] Satie's habit of embellishing the scores of his compositions with all kinds of written remarks became so established that he had to insist that they must not be read out during performances.[n 8]

In 1920 there was a festival of Satie's music at the Salle Erard in Paris.[57] In 1924 the ballets Mercure (with choreography by Massine and décor by Picasso) and Relâche ("Cancelled") (in collaboration with Francis Picabia and René Clair), both provoked headlines with their first night scandals.[8]

Despite being a musical iconoclast, and encourager of modernism, Satie was uninterested to the point of antipathy about innovations such as the telephone, the gramophone and the radio. He made no recordings, and as far as is known heard only a single radio broadcast (of Milhaud's music) and made only one telephone call.[13] Although his personal appearance was customarily immaculate, his room at Arcueil was in Orledge's word "squalid", and after his death the scores of several important works believed lost were found among the accumulated rubbish.[58] He was incompetent with money. Having depended to a considerable extent on the generosity of friends in his early years, he was little better off when he began to earn a good income from his compositions, as he spent or gave away money as soon as he received it.[13] He liked children, and they liked him, but his relations with adults were seldom straightforward. One of his last collaborators, Picabia, said of him:

Satie's case is extraordinary. He's a mischievous and cunning old artist. At least, that's how he thinks of himself. Myself, I think the opposite! He's a very susceptible man, arrogant, a real sad child, but one who is sometimes made optimistic by alcohol. But he's a good friend, and I like him a lot.[13]

Throughout his adult life Satie was a heavy drinker, and in 1925 his health collapsed. He was taken to the Hôpital Saint-Joseph in Paris, diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver. He died there at 8.00 p.m. on 1 July, at the age of 59.[59] He was buried in the cemetery at Arcueil.[60]

Works

Music

In the view of the Oxford Dictionary of Music, Satie's importance lay in "directing a new generation of French composers away from Wagner‐influenced impressionism towards a leaner, more epigrammatic style".[61] Debussy christened him "the precursor" because of his early harmonic innovations.[62] Satie summed up his musical philosophy in 1917:

To have a feeling for harmony is to have a feeling for tonality… the melody is the Idea, the outline; as much as it is the form and the subject matter of a work. The harmony is an illumination, an exhibition of the object, its reflection.[63]

Among his earliest compositions were sets of three Gymnopédies (1888) and his Gnossiennes (1889 onwards) for piano. They evoke the ancient world by what the critics Roger Nichols and Paul Griffiths describe as "pure simplicity, monotonous repetition, and highly original modal harmonies".[62] It is possible that their simplicity and originality were influenced by Debussy; it is also possible that it was Satie who influenced Debussy.[61] During the brief spell when Satie was composer to Péladan's sect he adopted a similarly austere manner.[61]

While Satie was earning his living as a café pianist in Montmartre he contributed songs and little waltzes. After moving to Arcueil he began to write works with quirky titles, such as the seven-movement suite Trois morceaux en forme de poire ("Three Pear-shaped Pieces") for piano four-hands (1903), simply-phrased music that Nichols and Griffiths describe as "a résumé of his music since 1890" – reusing some of his earlier work as well as popular songs of the time.[62] He struggled to find his own musical voice. Orledge writes that this was partly because of his "trying to ape his illustrious peers … we find bits of Ravel in his miniature opera Geneviève de Brabant and echoes of both Fauré and Debussy in the Nouvelles pièces froides of 1907".[8]

After concluding his studies at the Schola Cantorum in 1912 Satie composed with greater confidence and more prolifically. Orchestration, despite his studies with d'Indy, was never his strongest suit,[64] but his grasp of counterpoint is evident in the opening bars of Parade,[65] and from the outset of his composing career he had original and distinctive ideas about harmony.[66] In his later years he composed sets of short instrumental works with absurd titles, including Veritables Preludes flasques (pour un chien) ("True Flabby Preludes (for a Dog)", 1912), Croquis et agaceries d'un gros bonhomme en bois ("Sketches and Exasperations of a Big Wooden Man", 1913) and Sonatine bureaucratique ("Bureaucratic Sonata", 1917).

In his neat, calligraphic hand,[67] Satie would write extensive instructions for his performers, and although his words appear at first sight to be humorous and deliberately nonsensical, Nichols and Griffiths comment, "a sensitive pianist can make much of injunctions such as 'arm yourself with clairvoyance' and 'with the end of your thought'".[62] His Sonatine bureaucratique anticipates the neoclassicism soon adopted by Stravinsky.[8] Despite his rancorous falling out with Debussy, Satie commemorated his long-time friend in 1920, two years after Debussy's death, in the anguished "Elégie", the first of the miniature song cycle Quatre petites mélodies.[68] Orledge rates the cycle as the finest, though least known, of the four sets of short songs of Satie's last decade.[8]

Satie invented what he called Musique d'ameublement – "furniture music" – a kind of background not to be listened to consciously. Cinéma, composed for the René Clair film Entr'acte, shown between the acts of Relâche (1924), is an example of early film music designed to be unconsciously absorbed rather than carefully listened to.[69]

Satie is regarded by some writers as an influence on minimalism, which developed in the 1960s and later. The musicologist Mark Bennett and the composer Humphrey Searle have said that John Cage's music shows Satie's influence,[70] and Searle and the writer Edward Strickland have used the term "minimalism" in connection with Satie's Vexations, which the composer implied in his manuscript should be played over and over again 840 times.[71] John Adams included a specific homage to Satie's music in his 1996 Century Rolls.[72]

Writings

Satie wrote extensively for the press, but unlike his professional colleagues such as Debussy and Dukas he did not write primarily as a music critic. Much of his writing is connected to music tangentially if at all. His biographer Caroline Potter describes him as "an experimental creative writer, a blagueur[n 9] who provoked, mystified and amused his readers".[73] He wrote jeux d'esprit claiming to eat dinner in four minutes with a diet of exclusively white food (including bones and fruit mould), or to drink boiled wine mixed with fuchsia juice, or to be woken by a servant hourly throughout the night to have his temperature taken;[74] he wrote in praise of Beethoven's non-existent but "sumptuous" Tenth Symphony, and the family of instruments known as the cephalophones, "which have a compass of thirty octaves and are absolutely unplayable".[75]

Satie grouped some of these writings under the general headings Cahiers d'un mammifère (A Mammal's Notebook) and Mémoires d'un amnésique (Memoirs of an Amnesiac), indicating, as Potter comments, that "these are not autobiographical writings in the conventional manner".[76] He claimed the major influence on his humour was Oliver Cromwell, adding "I also owe much to Christopher Columbus, because the American spirit has occasionally tapped me on the shoulder and I have been delighted to feel its ironically glacial bite".[77]

His published writings include:

- A Mammal's Notebook: Collected Writings of Erik Satie (Serpent's Tail; Atlas Arkhive, No 5, 1997) ISBN 0-947757-92-9 (with introduction and notes by Ornella Volta, translations by Anthony Melville, contains several drawings by Satie)

- Correspondence presque complète: Réunie, établie et présentée par Ornella Volta (Paris: Fayard/Imes, 2000; 1265 pages) ISBN 2-213-60674-9 (an almost complete edition of Satie's letters, in French)

- Nigel Wilkins, The Writings of Erik Satie, London, 1980.

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Her death was mysterious: she was found drowned on the beach at Honfleur in unexplained circumstances.[3]

- "un vaste bâtiment très inconfortable et assez vilain à voir – une sorte de local pénitencier sans aucun agrément extérieur – ni intérieur du reste".[9]

- Satie's biographer Robert Orledge has conjectured that Satie had dyslexia, a condition that can make reading music as difficult as reading words.[13][14]

- Later he referred to himself at least once as a "phonometrician" (meaning "someone who measures sounds") after being called "a clumsy but subtle technician" in a book about contemporary French composers published in 1911.[23]

- "La vu s'étend jusqu'à la frontière belge".[28]

- Satie repeated this gesture twice – on the deaths of Charles Gounod in 1894 and Ambroise Thomas in 1896. Professors from the Conservatoire were elected on both occasions.[32]

- The pieces were the second Sarabande, the first prelude to Le Fils des étoiles and the third of the Gymnopédies.[45]

- He wrote in the first edition of Heures séculaires et instantanées, I forbid anyone to read the text aloud during the musical performance. Ignorance of my instructions will incur my righteous indignation against the presumptuous culprit. No exception will be allowed".[56]

- A blagueur is "a joker or prankster" according to the Merriam-Webster French-English dictionary.

References

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Rey, p. 11: "Erik Alfred Leslie Satie est né le 17 mai 1866 à Honfleur (Normandie) d'une mère anglaise et protestante, d'un père catholique et anglophobe, courtier maritime"

- Gillmor, p. xix

- Gillmor, p. 8

- Gillmor, p. 9

- Orledge, p. xix

- Orledge, Robert, revised by Caroline Potter. Satie, Erik (Eric) (Alfred Leslie)", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021

- Satie, p. 67

- Cooper, Martin, and Charles Timbrell. "Cortot, Alfred", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2001. Retrieved 20 September 2021 (subscription required)

- Orledge, p. xx

- Gillmor, p. xx

- Orledge, Robert. "Erik Satie: His music, the vision, his legacy" Archived 2020-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, Gresham College, 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021

- Ganschow, Leonore, Jenafer Lloyd-Jones, and T. R. Miles. "Dyslexia and Musical Notation", Annals of Dyslexia 1994, pp. 185–202 (subscription required)

- Gillmor, p. 33

- Harding, p. 35

- Rey, p. 22; and Gillmor, p. 64

- Gillmor, p. 12

- Templier, pp. 10–11

- Templier, p. 11

- Rey, p. 14

- Orledge, p. 6

- Innes and Shevtsova, p. 151

- Whiting, p. 172

- Rey, p. 33

- Gillmor, pp. 76–77

- Rey, p. 17

- Lajoinie, p. 21

- Whiting, p. 151

- Whiting, p. 156.

- Whiting, p. 152

- Pasler, Jann. "Dubois, (François Clément) Théodore", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 September 2021(subscription required); and Duchen, p. 120

- Rosinsky, p. 49

- Orledge, p. 157

- Giilmor, pp. 112–113

- Journey planner, ViaMichelin. Retrieved 17 September 2021

- Orledge, p. 233

- Templier, p. 56

- Gillmor, p. xxix

- Whiting, p. 259

- Rey, p. 61

- "Schola Cantorum" Archived 2021-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Orledge, pp. 86 and 95

- Kelly, Barbara L. "Ravel, Maurice", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 17 September 2021 (subscription required)

- "Courrier Musicale" Archived 2021-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Le Figaro, 14 January 1911, p. 7; and Gillmor, p. xxiii

- Orledge, p. 2

- Gillmor, p. 259; Potter (2017), p. 233; and Whiting, p. 493

- Nichols, p. 264

- Kelly, p. 15 (Ravel); and Schmidt, p. 13 (Auric and Poulenc)

- Lesure, p. 333

- Dietschy, p. 190

- Orledge, p. 255

- Gillmor, p. xxv

- "Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection" Archived 2015-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, Artic.edu. Retrieved 17 September 2021

- Orledge, p. xxxviii

- Williamson, p, 176

- Gillmor, p. xxiv

- Potter (2016), pp. 239 and 241

- Gillmor, p. 258

- Gillmor, p. 259

- Kennedy, Joyce, Michael Kennedy, and Tim Rutherford-Johnson. "Satie, Erik (Eric) Alfred Leslie", The Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford University Press, 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2021 (subscription required)

- Griffiths, Paul, and Roger Nichols. "Satie, Erik (Eric) (Alfred Leslie)", The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford University Press, 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2021 (subscription required)

- Quoted in Orledge, p. 68

- Orledge, p. 95; and Gillmor, p. 137

- Orledge, pp. 116 and 174

- Gillmor, p. 37

- Gillmor, p. 208

- Orledge, p. 39

- Shattuck, Roger. "Satie, Erik", The International Encyclopedia of Dance, Oxford University Press, 2005. Retrieved 18 September 2021 (subscription required)

- Bennett, p. 7

- Potter (2016), p. 230; and Strickland, p. 124

- Potter (2016), p. 252

- Potter (2016), pp. 206–207

- Weeks, pp. 83–84

- Dickinson, pp. 248 and 249

- Potter (2016), p. 207

- Quoted in Dickinson, p. 247

Sources

- Bennett, Mark (1995). A Brief History of Minimalism. Ann Arbor: UMI. OCLC 964203894.

- Dickinson, Peter (2016). Words and Music. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-106-1.

- Dietschy, Marcel (1999). A Portrait of Claude Debussy. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-315469-8.

- Duchen, Jessica (2000). Gabriel Fauré. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3932-5.

- Gillmor, Alan (1988). Erik Satie. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-9472-4.

- Harding, James (1975). Erik Satie. London: Secker & Warburg. OCLC 251432509.

- Innes, Christopher; Maria Shevtsova (2013). The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Directing. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84449-9.

- Kelly, Barbara L. (2000). "History and Homage". In Deborah Mawer (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-164856-1.

- Lajoinie, Vincent (1985). Erik Satie (in French). Lausanne: Age d'homme. OCLC 417094292.

- Lesure, François (2019). Claude Debussy: A Critical Biography. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-903-6.

- Nichols, Roger (2002). The Harlequin Years: Music in Paris 1917–1929. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51095-7.

- Orledge, Robert (1990). Satie the Composer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35037-2.

- Potter, Caroline (2016). Erik Satie: A Parisian Composer and his World. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-083-5.

- Potter, Caroline (2017). French Music Since Berlioz. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-09389-5.·

- Rey, Anne (1974). Erik Satie (in French). Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-000255-4.

- Rosinsky, Thérèse Diamand (1994). Suzanne Valadon. New York: Universe. ISBN 978-0-87663-777-7.

- Satie, Erik (1981). Ornella Volta (ed.). Écrits (second ed.). Paris: Éditions Champ libre. ISBN 978-2-85184-073-8.

- Strickland, Edward (2000). Minimalism: Origins. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21388-4.

- Templier, Pierre-Daniel (1969). Erik Satie. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. OCLC 1034659768.

- Weeks, David (1995). Eccentrics. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-81447-4.

- Whiting, Steven Moore (1999). Satie the Bohemian: From Cabaret to Concert Hall. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816458-6.

- Williamson, John (2005). Words and Music. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-619-1.

Further reading

- Shattuck, Roger (1958). The Banquet Years: The Arts in France, 1885–1918: Alfred Jarry, Henri Rousseau, Erik Satie, Guillaume Apollinaire. U.S.: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-394-70415-0.

- Shattuck, Roger (1968). The Banquet Years: The Origins of the Avant-Garde in France, 1885 to World War I. U.S.: Freeport, N.Y., Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 0836928261. Revised edition of 1958 book.

External links

- Free scores by Erik Satie at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Erik Satie in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- "Maisons Satie" Archived 13 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine – Satie birthplace museum, Honfleur.