Immigration to Finland

Immigration to Finland is the process by which people migrate to Finland to reside in the country. Some, but not all, become Finnish citizens. Immigration has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of Finland. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants, settlement patterns, impact on upward social mobility, crime, and voting behaviour.

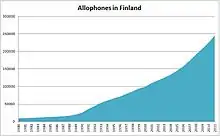

As of 2021, there are 469,633 foreigners residing in Finland, which corresponds to around 8.5% of the population. Numerous polls in 2010 indicated that the majority of the Finnish people want to limit immigration to the country in order to preserve its regional and native cultural diversity.[2] It was estimated in 2016 that by 2050, there will be 1–1.2 million foreigners in Finland.[3]

Immigrants from specific countries are divided into several ethnic groups. For example, there are both Turks and Kurds from Turkey, Moroccans and Berbers from Morocco. Immigrants from Iran are divided into Persians, Azeris, Kurds and Lurs.[4]

History

Under Swedish control

Under Swedish control, soldiers, priests and officers from Sweden started to arrive in Finland. With them came also Walloons. During this time Romanis migrated from Sweden to Finland. Nowadays there are around 10,000 Finnish Kale in Finland.[5] Many Germans, Norwegians, Danes, Swiss people, Poles, Dutch people and Scottish people settled in Finland during this period. Many big modern-day companies in Finland were started by these emigrants, including Finlayson, Fazer, Fiskars, Stockmann, Sinebrychoff, Stora Enso and Paulig.[6]

Under Russian control

When Finland became under Russian rule in the 1800s, Russians, Jews, Tatars and during World War I Chinese people started moving to Finland. This established small Jewish and Tatar communities in Finland. There are around 1,800 Jews and 1,000 Tatars living in Finland. When Finland gained independence in 1917, majority of the Russians and Chinese left Finland.[7]

After independence and WW1

Finland's first immigrants arrived in the years 1917–1922, thousands of Russians escaped to Finland as a result of the Russian Revolution. Many of them died in the Finnish Civil War. In the beginning of 1919, statistics showed there were 15,457 Russians in Finland, however the actual number was likely higher. The largest refugee flow was in 1922, when 33,500 crossed over the eastern border to Finland. The refugees were St. Petersburg Finns, Ingrian Finns, Karelians, officers, factory owners and nobles, among them was the cousin of the Romanov Family, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich. In 1921, after the Kronstadt rebellion, 6,400 seamen escaped over the frozen Gulf of Finland to Finland. Many of them integrated to the Finnish society, while others continued to Continental Europe. Between 1917 and 1939, 44,000 refugees sought asylum in Finland. In other estimates, between 1917 and 1939 as many as 100,000 sought security in Finland.[8]

Immigrant statistics from 1924:

| Country | 1924 |

|---|---|

| 16,921 | |

| 4,080 | |

| 1,645 | |

| 457 | |

| 379 | |

| 269 | |

| Total | 24,451 |

World War II

Immigrants from opposing sides of the war were sent to Internment camps and Nazi concentration camps in Nazi Germany. During the war, Ingrian Finns and Estonians migrated to Finland. Most of the people that did not manage to escape to the west were sent to the Soviet Union.[9] When Finland ceded parts of its territory to the Soviet Union, 430,000 people from there had to be evacuated. This was 12% of Finland's population at the time. When Finland annexed these parts back in the Continuation War, 260,000 of them returned home. After the Soviet Union annexed these parts again, the population there had to be evacuated yet again. These evacuees were housed and settled to the remaining parts of Finland by the state.[10]

After WW2

Immigration after the war stopped. The geopolitical state of the country and difficult economic situation did not attract immigrants. The number of foreign citizens during this time stayed stable, at 10,000. Between 1950 and 1975 it only grew by 1,000.

The immigration during the 1970s and 1980s consisted mainly by returning Finnish expats. Between 1981 and 1989, 70% of all immigration were Finns returning. In 1980, there were 12,843 foreign citizens. The largest groups were from Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and Denmark.[6]

| Country | 1980 |

|---|---|

| 3,105 | |

| 1,493 | |

| 980 | |

| 858 | |

| 403 | |

| 306 | |

| 290 | |

| 282 | |

| 275 | |

| 262 | |

| 252 | |

| 240 | |

| 162 | |

| 123 | |

| 114 | |

| 81 | |

| 44 | |

| 42 | |

| 38 | |

| 34 | |

| 31 | |

| 25 | |

| 20 | |

| Other Europe | 53 |

| Americas | 1,650 |

| Asia | 833 |

| Africa | 349 |

| Oceania | 157 |

| No citizenship | 340 |

| Unknown | 1 |

Refugee waves

The first refugee wave to Finland after the wars happened when the 1973 Chilean coup d'état started. 200 Chilean refugees arrived in Finland during the 1970s. They were not welcomed warmly, as they were one of Finland's very first non-white minorities. Most of the original 200 refugees returned to Chile. In 2017 there were 1,000 Chileans in Finland.[12]

The second, and much larger refugee wave happened when Vietnamese boat people came to Finland in the 1980s. Around 800 of them arrived. The Vietnamese community has grown into 10,817 by 2017.[13] In 1990 after the Breakup of Yugoslavia, thousands of refugees came to Finland, with most being Kosovars and Bosniaks. Immigrants from Yugoslavia now constitute the fourth or third largest immigrant group in Finland. They have established huge communities in Vantaa, Turku, Espoo and Närpes.[14]

The most notable refugee waves are from Somalia and Iraq. The first Somalis arrived to Finland via the Soviet Union. 90% of Somali refugees are illiterate when first arriving to Finland. Somali speaking population in Finland has grown from zero to 21,000 between 1990 and 2018. 55% of Somalis in Finland are unemployed, the highest of any ethnic group in Finland.

In 2014, Finland took 1,030 quota refugees, and an additional 3,651 people sought asylum. Of the asylum seekers, 1,346 were positive and 2,050 negative. Nearly one in two asylum seekers identity is not verified, mainly due to lack of passports. In 2008, 4,000 asylum seekers arrived in Finland. This grew to 6,000 in 2009, though it dropped to 4,000 in 2010. In 2011, 2012 and 2013 3,000 asylum seekers arrived in each year. The number grew to 32,400 in 2015, which was Europe's fourth largest in terms of population. It then dropped to 5,600 in 2016 and 5,100 in 2017.

On 13 September 2015, it was reported that the local authorities had estimated the flow of 300 asylum seekers per day entering via the northern land border from Sweden into Tornio, which is the main route of migration flow into Finland.[15] The total number of asylum seekers for the year was reported to be over 2.6 times the total amount for the whole of the previous year.[16] During October 2015, 7,058 new asylum seekers arrived in Finland. In mid-October the number of asylum seekers entering Finland during 2015 reached 27,000, which is, in relation to the country's size, the fourth-largest in Europe.[17] In late November, the number passed 30,000, nearly ten-fold increase compared to the previous year.[18][19]

More than 60% of asylum seekers who arrived during 2015 came from Iraq.[20] In late October, The Finnish Immigration Service (Migri) changed its guidelines about areas in Iraq which are recognised as safe by the Finnish authorities,[21] putting Iraqi asylum seekers under closer scrutiny.[22] The Interior Minister Petteri Orpo estimated that two in three of recent asylum seekers come to Finland in hopes of higher standard of living. In November, the Permanent Secretary of the Interior Ministry stated that approximately 60–65% of the recent applications for asylum will be denied.

In 2017, hundreds Muslim asylum seekers from Iraq and Afghanistan converted to Christianity after having had their first asylum application rejected by the Finnish Immigration Service (Migri), in order to re-apply for asylum on the grounds of religious persecution.[23]

| Country | 1990–2019 |

|---|---|

| 33,448 | |

| 11,007 | |

| 10,708 | |

| 9,504 | |

| 8,101 | |

| 3,504 | |

| 3,235 | |

| 3,172 | |

| 2,896 | |

| 2,813 | |

| 1,960 | |

| 1,953 | |

| 1,603 | |

| 1,569 | |

| 1,088 | |

| 1,034 | |

| 1,030 | |

| Other | 18,403 |

| Total | 117,028 |

Other refugee groups have arrived from Eritrea, Lebanon, DR Congo, Nigeria, Cameroon, Georgia and Pakistan.

EU membership and the 1990s

The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Since then immigration into Finland has greatly increased. By joining the Schengen Area, immigration to Finland has been easier. Finland allowed Ingrian Finns to migrate back to Finland as returnees. Since then, around 35,000 Ingrians have moved to Finland.

Finland joined the EU in 1995. This enabled freedom of movement. This has brought construction workers from France, Estonia and Poland.[26]

Change in immigrant population of the EU 2004 and 2007 enlargement countries between 2003 and 2021:

Estonia +41,837

Estonia +41,837 Romania +4,721

Romania +4,721 Poland +4,464

Poland +4,464 Latvia +3,234

Latvia +3,234 Bulgaria +2,524

Bulgaria +2,524 Hungary +1,789

Hungary +1,789 Lithuania +1,499

Lithuania +1,499 Czech Republic +751

Czech Republic +751 Slovakia +419

Slovakia +419 Slovenia +92

Slovenia +92 Cyprus +63

Cyprus +63 Malta +29

Malta +29

- Total +61,422

During 2021, 2,368 Estonian citizens, 655 Romanian citizens, 604 Latvian citizens and 453 Polish citizens immigrated to Finland. A total of 4,954 people immigrated from the Eastern EU member states, 61% of all incoming EU immigrants and 18% of all immigrants.[27]

Around 30,000 people migrate to Finland annually, with most coming from Iraq, Syria and Russia. While most immigrants are from Europe, 108,000 are from Asia and 50,000 from Africa.

Modern day

The most common reasons to immigrate to Finland were family reasons (32%), work (30%) and studying (21%).

In 2017, hundreds of Muslim asylum seekers from Iraq and Afghanistan converted to Christianity after having had their first asylum application rejected by the Finnish Immigration Service (Migri), in order to re-apply for asylum on the grounds of religious persecution.[28]

Chronology of 2015

- On 13 September 2015, it was reported that the local authorities had estimated the flow of 300 asylum seekers per day entering via the northern land border from Sweden into Tornio, which is the main route of migration flow into Finland.[29] The total number of asylum seekers for the year was reported to be over 2.6 times the total amount for the whole of the previous year.[30]

- During October 2015, 7,058 new asylum seekers arrived in Finland. In mid-October the number of asylum seekers entering Finland during 2015 reached 27,000, which is, in relation to the country's size, the fourth-largest in Europe.[31] In late November, the number passed 30,000, nearly ten-fold increase compared to the previous year.[32] In September, The Finnish Immigration Service (Migri) estimated that processing time of an asylum application may be extended from normal six months up to two years.[33] In late November, the reception centers were reported to be rapidly running out of space, forcing the authorities resorting to refurbished shipping containers and tents to house new asylum seekers.[32][34] The Interior Minister Petteri Orpo estimated that two in three asylum seekers come to Finland in hopes of higher standard of living.

- In November, the Permanent Secretary of the Interior Ministry stated that approximately 60–65% of the recent applications for asylum will be denied.[31] More than 60% of asylum seekers who arrived during 2015 came from Iraq.[21]

- In late October, The Finnish Immigration Service (Migri) changed its guidelines about areas in Iraq which are recognised as safe by the Finnish authorities,[21] putting Iraqi asylum seekers under closer scrutiny.[35]

- In late November, it was reported that more than 700 Iraqis had voluntarily cancelled their asylum applications during September and October. According to the officials of Migri, some of the Iraqi asylum seekers have had erroneous assumptions about the country's asylum policy.[21]

- On 22 November 2015, it was reported that Finland had appealed to Russia with a proposal to prohibit the crossings at some of the land borders by bicycle.[36]

- On 27 December 2015, it was reported that Finland had blocked access for people to cross over two Russian border crossings (Raja-Jooseppi and Salla) by bicycles. Many asylum seekers were reported to have earlier crossed the border by bicycles.[37]

- On 3 December, the Interior Minister Petteri Orpo announced that special repatriation centers would be established. These centers would be inhabited by the asylum seekers whose applications were declined. While he stressed that these camps would not be prisons, he described the inhabitants would be under strict surveillance.[38]

- On 4 December 2015, Finland reportedly closed one of its northern border checkpoints before the scheduled time along the Finnish–Russian border. According to Russian media, due to the closure, asylum seekers could not enter the country.[39]

- On 12 December 2015, Finnish Interior Minister Petteri Orpo announced that if the external borders of EU cannot be secured, then Schengen, Dublin and in a way the whole EU is under serious threat. Further he noted that Finland has imprisoned two asylum seekers, charging them with 11 cases of murder. According to Orpo, because of the failure in registering asylum seekers at the external borders, they can travel all the way to Finland via northern Sweden. He noted that border controls have been improved in harbours, airports and land border crossings with Sweden.[40][41][42]

Chronology of 2016

- On 2 January 2016, it was reported that Finland had issued a command for the Finnlines ferry crossing from Germany to Finland to refuse boarding asylum seekers without visa. German NGOs criticised the decision, and it was still unclear how it could be enforced, especially as a direct visa from Germany to Finland is not available.[43]

- On 23 January 2016, it was reported, that Finnish Foreign Minister Timo Soini concluded that "closing the eastern border is possible". He stated that if an asylum seeker does not have need for protection, they will lose their money and get themselves deported. As Finland was struggling with a declining economy and increasing unemployment, he noted that resources of police forces, border control, security "need to be organized".[44] On 24 January, YLE, Finland's national public-broadcasting company, reported that a Russian border guard had admitted that the Federal Security Service was enabling migrants to enter Finland.[45]

- On 23 February, the Finnish press reported that the profile of national origin of asylum seekers had changed, with a rise of Indian and Bangladeshi asylum seekers, so that the third largest group of asylum seekers after Afghans and Iraqis were Indians, the fourth Syrians and the fifth Bangladeshis.[46]

Demographics

Sources of immigration

Adoption

Between 1987 and 2021, a total of 5,708 people were adopted in Finland who were born in another country. This comprised 42% of all adoptions during the time period.[48]

Adoptions by country of birth 1987–2021:

China (1,033)

China (1,033) Russia (860)

Russia (860) Thailand (785)

Thailand (785) Colombia (594)

Colombia (594) South Africa (541)

South Africa (541) Soviet Union (288)

Soviet Union (288) Ethiopia (287)

Ethiopia (287) Philippines (239)

Philippines (239) India (202)

India (202) Estonia (152)

Estonia (152)

608 were adopted from other countries while for 119 adoptions the country was unknown.

Countries of origin

| Country | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9,987 | 37,783 | 63,665 | 94,304 | |

| 0 | 10,839 | 29,080 | 51,805 | |

| 24,541 | 28,040 | 31,160 | 33,692 | |

| 203 | 3,686 | 9,127 | 26,653 | |

| 49 | 6,256 | 12,868 | 23,409 | |

| 128 | 5,538 | 10,340 | 15,811 | |

| 441 | 2,291 | 6,926 | 14,339 | |

| 1,841 | 4,079 | 6,566 | 13,291 | |

| 5 | 384 | 3,421 | 12,044 | |

| 387 | 1,794 | 6,747 | 11,974 | |

| 412 | 2,323 | 6,072 | 11,392 | |

| 434 | 1,182 | 4,306 | 10,749 | |

| 516 | 2,650 | 5,164 | 10,129 | |

| 38 | 211 | 521 | 9,332 | |

| 2,437 | 3,582 | 5,921 | 7,402 | |

| 1,638 | 2,731 | 4,547 | 7,208 | |

| 0 | 961 | 2,103 | 7,202 | |

| 248 | 752 | 1,775 | 7,087 | |

| 2,398 | 2,903 | 4,082 | 6,217 | |

| 965 | 1,193 | 2,880 | 5,807 | |

| 153 | 760 | 1,880 | 5,628 | |

| 6 | 89 | 1,176 | 5,012 | |

| 130 | 436 | 1,514 | 4,882 | |

| 95 | 479 | 1,673 | 4,731 | |

| 89 | 303 | 1,496 | 4,607 | |

| 395 | 1,151 | 2,136 | 4,106 | |

| 6 | 451 | 1,548 | 4,068 | |

| 9 | 256 | 1,071 | 3,626 | |

| 475 | 958 | 1,790 | 3,395 | |

| 473 | 779 | 1,650 | 3,371 | |

| 507 | 1,089 | 1,936 | 3,129 | |

| 248 | 508 | 1,169 | 3,123 | |

| 108 | 642 | 1,455 | 3,100 | |

| 540 | 933 | 1,669 | 2,777 | |

| 67 | 322 | 1,070 | 2,611 | |

| 153 | 289 | 980 | 2,368 | |

| 7 | 73 | 1,425 | 2,154 | |

| 0 | 204 | 786 | 2,130 | |

| 11 | 72 | 1,227 | 2,080 | |

| 71 | 173 | 881 | 2,062 | |

| 852 | 954 | 1,520 | 1,971 | |

| 391 | 732 | 1,272 | 1,874 | |

| 195 | 422 | 808 | 1,808 | |

| 302 | 468 | 698 | 1,779 | |

| 4 | 33 | 600 | 1,773 | |

| 905 | 1,181 | 1,453 | 1,755 | |

| 107 | 330 | 773 | 1,704 | |

| 0 | 17 | 94 | 1,680 | |

| 240 | 507 | 997 | 1,547 | |

| 210 | 467 | 826 | 1,521 | |

| 0 | 42 | 197 | 1,465 | |

| 426 | 656 | 960 | 1,402 | |

| 124 | 418 | 854 | 1,380 | |

| 0 | 1,627 | 1,779 | 1,329 | |

| 23 | 206 | 492 | 1,281 | |

| 409 | 615 | 912 | 1,247 | |

| 63 | 153 | 518 | 1,224 | |

| 108 | 208 | 621 | 1,216 | |

| 145 | 312 | 671 | 1,197 | |

| 527 | 708 | 865 | 1,167 | |

| 245 | 342 | 611 | 1,139 | |

| 0 | 91 | 159 | 1,129 | |

| 54 | 118 | 349 | 937 | |

| 109 | 325 | 537 | 903 | |

| 36 | 108 | 348 | 896 | |

| 34 | 133 | 332 | 876 | |

| 107 | 206 | 452 | 852 | |

| 330 | 465 | 708 | 795 | |

| 0 | 12 | 100 | 778 | |

| 0 | 167 | 393 | 739 | |

| 83 | 200 | 433 | 736 | |

| 238 | 312 | 512 | 715 | |

| 0 | 0 | 894 | 715 | |

| 0 | 51 | 258 | 711 | |

| 3 | 143 | 497 | 684 | |

| 66 | 176 | 402 | 678 | |

| 183 | 227 | 369 | 668 | |

| 17 | 153 | 359 | 637 | |

| 56 | 146 | 424 | 630 | |

| 16 | 201 | 243 | 599 | |

| 134 | 224 | 372 | 585 | |

| 2 | 29 | 238 | 576 | |

| 101 | 157 | 290 | 571 | |

| 42 | 70 | 148 | 547 | |

| 0 | 260 | 281 | 535 | |

| 0 | 295 | 318 | 490 | |

| 51 | 135 | 253 | 458 | |

| 78 | 149 | 283 | 429 | |

| 3 | 23 | 38 | 423 | |

| 7 | 29 | 145 | 416 | |

| 14 | 34 | 107 | 388 | |

| 13 | 36 | 78 | 353 | |

| 3 | 49 | 116 | 330 | |

| 19 | 68 | 162 | 313 | |

| 29 | 60 | 148 | 308 | |

| 34 | 86 | 178 | 294 | |

| 15 | 45 | 150 | 292 | |

| 10 | 34 | 123 | 272 | |

| 0 | 144 | 199 | 270 | |

| 9 | 41 | 121 | 240 | |

| 0 | 10 | 83 | 228 | |

| 40 | 76 | 121 | 228 | |

| 74 | 120 | 150 | 199 | |

| 5 | 49 | 86 | 198 | |

| 20 | 52 | 119 | 194 | |

| 15 | 50 | 122 | 191 | |

| 6 | 46 | 138 | 191 | |

| 0 | 10 | 80 | 184 | |

| 12 | 50 | 98 | 179 | |

| 17 | 18 | 114 | 172 | |

| 48 | 29 | 71 | 170 | |

| 9 | 23 | 62 | 168 | |

| 0 | 65 | 65 | 163 | |

| 0 | 25 | 85 | 162 | |

| 3 | 6 | 49 | 159 | |

| 4 | 9 | 55 | 153 | |

| 4 | 15 | 37 | 144 | |

| 32 | 51 | 80 | 134 | |

| 0 | 5 | 80 | 133 | |

| 18 | 32 | 75 | 122 | |

| 3 | 14 | 56 | 114 | |

| 1 | 16 | 48 | 111 | |

| 1 | 7 | 32 | 108 | |

| 8 | 21 | 31 | 84 | |

Distribution

| № | Municipality | Immigrants | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Helsinki | 116,004 | 17.6 |

| 2. | Espoo | 59,837 | 20.1 |

| 3. | Vantaa | 56,027 | 23.4 |

| 4. | Turku | 25,756 | 13.2 |

| 5. | Tampere | 20,935 | 8.6 |

| 6. | Oulu | 10,245 | 4.9 |

| 7. | Lahti | 9,645 | 8.0 |

| 8. | Jyväskylä | 8,219 | 5.7 |

| 9. | Vaasa | 6,793 | 10.0 |

| 10. | Lappeenranta | 6,073 | 8.4 |

Immigrants overwhelmingly settle in cities; 85% of immigrants in Finland live in cities and their surroundings. Only 11% live in the countryside, with most of them being from other European countries. Immigrants from the Middle East and Africa are the most heavily concentrated group in cities.[51]

Employment

The most common job for immigrants in 2017 was real estate cleaner, at 11,328. The second most common was restaurant jobs at 10,696, and the third was labour hire at 8,437. Immigrants make up 26.9% of real estate cleaners, despite only making up 6.3% of the population.[52]

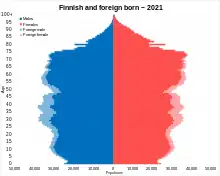

Around 20,000 immigrants in Finland are searching for jobs.[53] Around 70% of net immigrants are in the working age (18–64), and most of them are young adults.[54]

The unemployment rate among Finnish-born was 12.4% in 2020, while it was 23.6% among immigrants born abroad. Immigrants from other EU-countries had the lowest unemployment rate (16.9%), while African immigrants had the highest rate (32.5%).[55]

Immigrant languages

Immigration has greatly increased the number of languages spoken in Finland. In 1990, there were 6 foreign languages in Finland with over 1,000 speakers. In 2021, that number has jumped to 46. The most spoken immigrant languages are Russian (87,600), Estonian (50,200), Arabic (36,500), English (25,600), Somali (23,700), Persian (16,400) and Kurdish (16,000). In total 458,000 people speak an immigrant language, which is 8.3% of the population.

In 1990, the most spoken ones were Russian (3,900), English (3,600), German (2,400), Vietnamese (1,600), Estonian (1,400) and Arabic (1,100). The total number of foreign language speakers was less than 25,000 (0.5%).[56]

Citizenship

From 1990 to 2021, a total of 159,342 foreigners have acquired Finnish citizenship. In 2018, 97% of foreigners who were granted Finnish citizenship, kept their previous nationality.[57] Finland had the fourth highest naturalisation rate in the EU in 2020.[58] 16% of Finnish citizenships granted were granted to other EU citizens in 2021.

| Country | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,728 | 2,028 | 2,758 | 1,766 | 1,946 | 1,546 | 1,161 | |

| 560 | 534 | 742 | 621 | 589 | 602 | 744 | |

| 955 | 1,066 | 957 | 856 | 583 | 541 | 436 | |

| 420 | 459 | 705 | 541 | 658 | 516 | 370 | |

| 28 | 47 | 118 | 118 | 299 | 205 | 360 | |

| 165 | 206 | 212 | 210 | 248 | 196 | 282 | |

| 242 | 376 | 469 | 339 | 309 | 264 | 227 | |

| 150 | 193 | 261 | 249 | 281 | 304 | 209 | |

| 145 | 163 | 281 | 202 | 255 | 220 | 171 | |

| 140 | 222 | 309 | 244 | 205 | 156 | 155 | |

| 146 | 225 | 249 | 197 | 221 | 148 | 140 | |

| 229 | 264 | 313 | 210 | 260 | 172 | 125 | |

| 74 | 123 | 178 | 125 | 132 | 119 | 106 | |

| 137 | 193 | 245 | 154 | 174 | 181 | 105 | |

| 79 | 106 | 141 | 182 | 225 | 124 | 97 | |

| 131 | 150 | 223 | 183 | 138 | 100 | 96 | |

| 73 | 108 | 42 | 183 | 214 | 134 | 81 | |

| 26 | 31 | 147 | 134 | 211 | 126 | 80 | |

| 100 | 140 | 176 | 105 | 97 | 72 | 80 | |

| 179 | 175 | 283 | 157 | 113 | 100 | 67 | |

| 135 | 143 | 228 | 110 | 121 | 70 | 59 | |

| 56 | 87 | 118 | 80 | 53 | 39 | 58 | |

| 61 | 69 | 111 | 72 | 93 | 64 | 55 | |

| 77 | 67 | 110 | 71 | 77 | 69 | 43 | |

| 66 | 83 | 87 | 120 | 66 | 84 | 37 | |

| 130 | 140 | 190 | 91 | 89 | 70 | 35 | |

| 89 | 129 | 130 | 162 | 105 | 75 | 35 | |

| 63 | 90 | 112 | 80 | 61 | 38 | 20 | |

| Total | 7,921 | 9,375 | 12,219 | 9,211 | 9,649 | 7,816 | 6,643 |

Effects of immigration

Costs

According to a macroeconomic study immigrants, refugees and migrants, arriving Finland benefits its economy within five years of arrival. In the case of asylum seekers the reach positive effect to the economy takes longer, from three to seven years. In Finland, asylum seekers face many restrictions on working that slows down their possibilities to contribute to the economy.[60]

Most of immigration's cost to the society consists of welfare. Because immigrant families have on average more children than their Finnish counterparts, they receive more welfare.[61] Income support, housing benefits and unemployment benefits of immigrants cost nearly 300 million euros in 2009, and the social and health benefits of immigrants cost 200 million euro annually. Around 110–112 million euros goes to refugee quotas.[62]

According to the Ministry of the Interior (Finland) in 2009, asylum seekers in Finland during their asylum process received one of the highest rates of benefits in Europe.[63]

Crime

First records of immigrant crime was in 1919–1932, when the Prohibition in Finland started. Most of the alcohol were smuggled from Estonia or other European countries, like Poland and Germany. The smugglers were usually Finns, Germans, Swedes or Estonians.[64] In the late 1990s, Estonia became a transit country for drugs that were brought to Finland. Both Finns and Estonians have managed the trade together.[65]

In the last 10 years immigrant crime has increased by 56%. As high as 90% of burglaries in Finland are done by immigrants.[66]

In 2016, illegal drugs like Rivotril were beginning to be sold in Helsinki Railway Square, Itäkeskus and Kallio by foreigners from Central Europe. Furthermore, seizures of cocaine have been increasing to some extent in recent years.[67]

In 2011, of all the immigrants in prison, 27% were Estonian citizens, 13% Romanian citizens, 10% Russian citizens and 6% Lithuanian citizens.[68]

Even though less than 5% of the Finnish population consists of foreign citizens, they account for 25% of reported sex crimes. In 2018, 1393 cases of rape were reported to the police.[69] According to official statistics from 2005, 27% of all rapes in Finland were committed by foreigners, even though they only comprised 2.2% of the population back then.[70] Many of them are Afghans, Iraqis and Turks.[71][72]

Discrimination

According to a study done by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights in 2017, 60% of Sub-Saharan African immigrants in Finland had experienced discrimination in the past five years. This was significantly higher than the EU average of 39%. Women and first-generation immigrants experienced the most discrimination. Most discrimination was faced in public and private services. It was also experienced during studying, job seeking and at work. Most discrimination goes unreported, though the ones living in Finland reported the most. Roughly a third of respondents had reported their discrimination.[74]

24.1% of Finnish women with a foreign-background and 32.4% of men had experienced physical or psychological abuse over the previous year in 2018. Asian women (excluding West Asia) experienced the least amount of abuse (19.7%) while Sub-Saharan African men experienced the most (49%). Harassment experienced by people with a foreign-background varies depending on the region. Foreigners in Ostrobothnia had the lowest share of people who had experienced abuse (15.2%) while those in Päijät-Häme had the highest share (32.1%). The region which contains the vast majority of foreigners had the second highest share (30.3%).[75]

Public opinion

In 1993, Finns were most accepting of Norwegian, Ingrian, British, American and Swedish migrants. They were least accepting of Russian, Yugoslavian, Turkish, African, Vietnamese and Chilean migrants.[14]

In a 2015 online survey by YLE, Finns were most accepting of German, Swedish, Estonian, British and US American immigrants. In the same survey Iran, Iraq and Romania were the least accepted countries of origin of foreign immigrants.[76]

According to a 2016 poll, many Finns were concerned simultaneously about unemployed immigrants and immigrants taking local jobs.[77]

See also

References

- Rapo, Markus. "Statistikcentralen -". Stat.fi. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- "HS.fi". Archived from the original on 2010-10-21. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- "Varissuo on maahanmuuton mallioppilas". ts.fi. March 24, 2016.

- Huttunen, Markku. "Statistics Finland - Statistics". www.stat.fi.

- Vilkuna, Kustaa H. J.: Arkielämää patriarkaalisessa työmiesyhteisössä: rautaruukkilaiset suurvalta-ajan Suomessa. Helsinki: Suomen historiallinen seura, 1996.

- "Maahanmuuton historia Suomessa Jouni Korkiasaari (2017)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- JYRKI PAASKOSKI: Vanhan Suomen donataarit ja tilanhoitajat – katsaus aatelisten lahjoitusmaatalouteen vuosina 1710–1811 Archived 2007-10-26 at the Wayback Machine - Genos 64 (1993), s. 138–152

- Leitzinger, Antero (2008), Ulkomaalaispolitiikka Suomessa 1812–1972, Helsinki: East-West Books.

- Leo Yllö: Inkerin maa ja luonto. – Inkerin suomalaisten historia. Inkerin kulttuuriseura, Helsinki 1969

- Seppo Varjus: Vieroksutut evakot. Evakot: Ilta-Sanomien erikoislehti 3. joulukuuta 2015, s. 52–54. Helsinki: Sanoma Media Finland.

- Statistical Yearbook of Finland (PDF). Helsinki, Finland: Tilaskokeskus. 2014. ISBN 978-952-244-516-2.

- "Ensimmäiset pakolaiset tulivat Suomeen Chilestä 1970-luvulla – "Meitä pelättiin, eikä linja-autossa istuttu viereen"". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 30 August 2015.

- "Ensimmäiset pakolaiset olleet Suomessa jo yli 40 vuotta – vietnamilaiset sopeutuivat, somalit kohtasivat ennakkoluuloja". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 25 October 2015.

- "Ohjataan uudelleen..." otavanopisto.muikkuverkko.fi.

- Sami Koski (2015-09-13). "Turvapaikanhakijoiden määrä räjähti Torniossa: "Satoja tullut tänään"". Iltalehti. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- Olli Waris (2015-09-14). "Viime viikolla ennätyksellinen määrä turvapaikanhakijoita". Iltalehti. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Interior Ministry: Finland set to reject two thirds of asylum seekers". YLE. 2015-11-11. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Eurajoki resorting to containers to house asylum seekers". YLE. 2015-11-13. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Reception centres use containers to house new arrivals". YLE. 2015-11-28. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Disappointed Iraqis cancel asylum applications". YLE. 2015-11-24. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Disappointed Iraqis cancel asylum applications". YLE. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Finland adopts one-stop approach to slash asylum processing queues". YLE. 2015-11-30. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Stort finländskt fenomen - hundratals muslimer blir kristna". 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018.

- "Turvapaikanhakijat - Euroopan muuttoliikeverkosto". www.emn.fi.

- "Tilastot — Maahanmuuttovirasto". tilastot.migri.fi.

- "Muuttoliike". www.stat.fi.

- "11vz -- Maahan- ja maastamuutto muuttomaan, sukupuolen ja kansalaisuuden mukaan, 1990-2021 (in Finnish)". Stat.fi. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "Stort finländskt fenomen - hundratals muslimer blir kristna". 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018.

- Sami Koski (13 September 2015). "Turvapaikanhakijoiden määrä räjähti Torniossa: "Satoja tullut tänään"". Iltalehti. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Olli Waris (14 September 2015). "Viime viikolla ennätyksellinen määrä turvapaikanhakijoita". Iltalehti. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Interior Ministry: Finland set to reject two thirds of asylum seekers". YLE. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Reception centres use containers to house new arrivals". YLE. 28 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Turvapaikkahakemusten käsittelyajat venyvät – "Täällä on tuhansia turvapaikanhakijoita monta vuotta"". YLE. 10 September 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Eurajoki resorting to containers to house asylum seekers". YLE. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Finland adopts one-stop approach to slash asylum processing queues". YLE. 30 November 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Border Guard: Rise in Syrians entering Finland illegally through Russia". YLE. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Finland prohibits crossing border with Russia on bikes - media". TASS. 27 December 2015. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Interior Minister: Finland to set up asylum seeker repatriation centres". YLE. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "TASS: World - Finnish border guards block 15 Mideast, African immigrants in Russia's Murmansk region". TASS. 5 December 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Markku Saarinen (12 December 2015). "Orpo Ylellä: EU:lla kriittiset hetket keväällä - "Schengen vakavasti uhattuna"". Iltalehti. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Olli Waris (12 December 2015). "11 murhasta epäillyt kaksoset: oikeudenkäynti Suomessa". Iltalehti. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Antti Honkamaa (12 December 2015). "Ministeri Orpo Ylellä: Tämän takia Isis-murhaajiksi epäillyt onnistuivat tulemaan Suomeen". Ilta-Sanomat. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Maria Gestrin-Hagner (2 January 2016). "Visumkrav satte stopp för flyktingar från Tyskland". Hbl.fi - Finlands ledande nyhetssajt på svenska. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Maarit Simoska (23 January 2016). "Soini: Itärajan sulkeminen on mahdollista - video". Iltalehti. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Russian border guard to STT: Russian security service behind northeast asylum traffic". YLE. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Rajalla uusi havainto: turvapaikanhakijoita saapuu Suomeen nyt myös Intiasta". Iltalehti. 23 February 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- "Immigration and emigration by country of departure or arrival, age group and region, 1990–2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "Adoptions by country of birth, age group and sex of child and type of adoption, 1987-2021". stat.fi. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- "Origin and background country by sex, by municipality, 1990–2021". Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 2022-06-01. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- "Key figures on population by region, 1990–2021". Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 2019-04-06. Retrieved 2022-06-08.

- Juopperi, Jukka (2019-02-07). "Maahanmuuttajat suuntaavat kaupunkeihin – Euroopasta tulleita asettunut maaseudullekin". Tieto & Trendit (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Hiitola, Netta. "Tilastokeskus - Työssäkäynti 2017". www.stat.fi.

- "Poliisiylijohtaja Mikko Paatero haluaa lisää maahanmuuttajia poliisin palvelukseen".

- Myrskylä, Pekka (2015-09-30). "Mihin maahanmuuttajia tarvitaan kun meillä on 350 000 työtöntä?". Tieto & Trendit (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Unemployment rate" (in Finnish). Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- Statistics Finland

- "Liki kaikki Suomen kansalaisuuden saaneet säilyttävät entisen kansalaisuutensa". 13 September 2019.

- "Citizenship granted to 729 000 people in 2020".

- "Citizenships granted according to previous nationality, 1990-2021". stat.fi. Statistics Finland. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- Maxmen, Amy (2018-06-20). "Migrants and refugees are good for economies". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05507-0. S2CID 169653469.

- "Maahanmuuton hinta". yle.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Raportti: Maahanmuutto hyödyttää julkista taloutta". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 18 June 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Turvapaikanhakija saa Suomessa eniten". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 21 November 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Toomas Hiio: 150 aastat Eesti Üliõpilaste Seltsi asutamisest". Tuglas-Seura.

- "T lt tulevat huumeet Suomeen | Uutiset | Iltalehti.fi". Archived from the original on 2009-12-18.

- "Poliisi: Suurin osa asuntomurroista ulkomaista käsialaa". Yle Uutiset. 19 January 2015.

- "Finland Country Drug Report 2019". emcdda.europa.eu. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "National Enforcement Authority Finland". National Enforcement Authority Finland.

- "Development of selected offences". stat.fi. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- Hannu Niemi. Rikollisuustilanne Suomessa — II.B.3. Oikeuspoliittinen tutkimuslaitos 2005. "Oikeuspoliittinen tutkimuslaitos - RIKOLLISUUSTILANNE 2005". Archived from the original on 2007-05-02. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- Viljakainen, Miika; Lakka, Päivi (2018-12-15). "Iso selvitys ulkomaalaisten seksuaalirikollisuudesta – määrät, syyt, ratkaisukeinot". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Statistics Finland: Rape reports increased by 7.5% in Finland in 2017–2018". www.helsinkitimes.fi. 18 January 2019.

- "Mikko Urmi Photography" (PDF).

- "Raportti: Suomi Euroopan kärjessä maahanmuuttajien syrjinnässä" (in Finnish). Ihmisoikeusliitto. 11 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- "Experienced harassment". Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- Raivio, Petri (22 April 2015). "Maahanmuuton vastustajat: Saksalaisia voisimme ehkä ottaa vastaan" (in Finnish). Yle. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- "Do refugees take away jobs?". Debating Europe. 4 April 2018.