Santali language

Santali (Pronounced: [santaɽi], Ol Chiki: ᱥᱟᱱᱛᱟᱲᱤ), Bengali: সাঁওতালী, Odia: ସାନ୍ତାଳୀ, Devanagari: सान्ताळी, also known as Santal or Santhali, is the most widely-spoken language of the Munda subfamily of the Austroasiatic languages, related to Ho and Mundari, spoken mainly in the Indian states of Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Mizoram, Odisha, Tripura and West Bengal[5] by Santals. It is a recognised regional language of India per the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.[6] It is spoken by around 7.6 million people in India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal, making it the third most-spoken Austroasiatic language after Vietnamese and Khmer.[5]

| Santali | |

|---|---|

| ᱥᱟᱱᱛᱟᱲᱤ, সাওঁতালী, ସାନ୍ତାଳୀ, চাওঁতালি | |

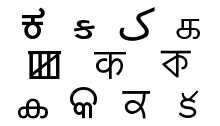

The word "Santali" in Ol Chiki script | |

| Native to | India, Bangladesh, Nepal |

| Ethnicity | Santal |

Native speakers | 7.6 million (2011 census[1])[2] |

Austroasiatic

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Official: Ol Chiki script[3] Others: Bengali-Assamese script,[4] Odia script, Roman script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | sat |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:sat – Santalimjx – Mahali |

| Glottolog | sant1410 Santalimaha1291 Mahali |

| Part of a series on | |

|---|---|

| |

| Constitutionally recognised languages of India | |

| Category | |

| 22 Official Languages of the Indian Republic | |

| Related | |

Santali was a mainly oral language until the development of the Ol Chiki script by Pandit Raghunath Murmu in 1925. Ol Chiki is alphabetic, sharing none of the syllabic properties of the other Indic scripts, and is now widely used to write Santali in India.

History

According to linguist Paul Sidwell, Munda languages probably arrived on the coast of Odisha from Indochina about 4000–3500 years ago, and spread after the Indo-Aryan migration to Odisha.[7]

Until the nineteenth century, Santali had no written language and all shared knowledge was transmitted by word of mouth from generation to generation. European interest in the study of the languages of India led to the first efforts at documenting the Santali language. Bengali, Odia and Roman scripts were first used to write Santali before the 1860s by European anthropologists, folklorists and missionaries including A. R. Campbell, Lars Skrefsrud and Paul Bodding. Their efforts resulted in Santali dictionaries, versions of folk tales, and the study of the morphology, syntax and phonetic structure of the language.

The Ol Chiki script was created for Santali by Mayurbhanj poet Raghunath Murmu in 1925 and first publicised in 1939.[8]

Ol Chiki as a Santali script is widely accepted among Santal communities. Presently in West Bengal, Odisha, and Jharkhand, Ol Chiki is the official script for Santali literature & language.[9][10] However, users from Bangladesh use Bengali script instead.

Santali was honoured in December 2013 when the University Grants Commission of India decided to introduce the language in the National Eligibility Test to allow lecturers to use the language in colleges and universities.[11]

Geographic distribution

The highest concentrations of Santali language speakers are in Santhal Pargana division, as well as East Singhbhum and Seraikela Kharsawan districts of Jharkhand, the Jangalmahals region of West Bengal (Jhargram, Bankura and Purulia districts) and Mayurbhanj district of Odisha.

Smaller pockets of Santali language speakers are found in the northern Chota Nagpur plateau (Hazaribagh, Giridih, Ramgarh, Bokaro and Dhanbad districts), Balesore and Kendujhar districts of Odisha, and throughout western and northern West Bengal (Birbhum, Paschim Medinipur, Hooghly, Paschim Bardhaman, Purba Bardhaman, Malda, Dakshin Dinajpur, Uttar Dinajpur, Jalpaiguri and Darjeeling districts), Banka district and Purnia division of Bihar (Araria, Katihar, Purnia and Kishanganj districts), and tea-garden regions of Assam (Kokrajhar, Sonitpur, Chirang and Udalguri districts). Outside India, the language is spoken in pockets of Rangpur and Rajshahi divisions of northern Bangladesh as well as the Morang and Jhapa districts in the Terai of Province No. 1 in Nepal.[12][13]

Santali is spoken by over seven million people across India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and Nepal.[5] According to 2011 census, India has a total of 7,368,192 Santali speakers (including 3,58,579 Karmali, 26,399 Mahli).[14][15] State wise distribution is Jharkhand (2.75 million), West Bengal (2.43 million), Odisha (0.86 million), Bihar (0.46 million), Assam (0.21 million) and a few thousand in each of Chhattisgarh, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh and Tripura.[16]

Official status

Santali is one of India's 22 scheduled languages.[6] It is also recognised as the additional official language of the states of Jharkhand and West Bengal.[17][18]

Phonology

Consonants

Santali has 21 consonants, not counting the 10 aspirated stops which occur primarily, but not exclusively, in Indo-Aryan loanwords and are given in parentheses in the table below.[21]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɳ)* | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Stop | voiceless | p (pʰ) | t (tʰ) | ʈ (ʈʰ) | c (cʰ) | k (kʰ) | |

| voiced | b (bʱ) | d (dʱ) | ɖ (ɖʱ) | ɟ (ɟʱ) | ɡ (ɡʱ) | ||

| Fricative | s | h | |||||

| Trill/Flap | r | ɽ | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||

In native words, the opposition between voiceless and voiced stops is neutralised in word-final position. A typical Munda feature is that word-final stops are "checked", i. e. glottalised and unreleased.

Morphology

Santali, like all Munda languages, is a suffixing agglutinating language.

Nouns

Nouns are inflected for number and case.[22]

Number

Three numbers are distinguished: singular, dual and plural.[23]

| Singular | ᱥᱮᱛᱟ | 'dog' |

|---|---|---|

| Dual | ᱥᱮᱛᱟᱼᱠᱤᱱ | 'two dogs' |

| Plural | ᱥᱮᱛᱟᱼᱠᱚ | 'dogs' |

Case

The case suffix follows the number suffix. The following cases are distinguished:[24]

| Case | Marker | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -Ø | Subject and object |

| Genitive | ᱼᱨᱮᱱ (animate) ᱼᱟᱜ, ᱼᱨᱮᱭᱟᱜ (inanimate) |

Possessor |

| Comitative | ᱼᱴᱷᱮᱱ/ -ᱴᱷᱮᱡ | Goal, place |

| Instrumental-Locative | ᱼᱛᱮ | Instrument, cause, motion |

| Sociative | ᱼᱥᱟᱶ | Association |

| Allative | ᱼᱥᱮᱱ/ᱼᱥᱮᱡ | Direction |

| Ablative | ᱼᱠᱷᱚᱱ/ᱼᱠᱷᱚᱡ | Source, origin |

| Locative | ᱼᱨᱮ | Spatio-temporal location |

Transcript version:

| Case | Marker | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -Ø | Subject and object |

| Genitive | -rɛn (animate) -ak', -rɛak' (inanimate) |

Possessor |

| Comitative | -ʈhɛn/-ʈhɛc' | Goal, place |

| Instrumental-Locative | -tɛ | Instrument, cause, motion |

| Sociative | -são | Association |

| Allative | -sɛn/-sɛc' | Direction |

| Ablative | -khɔn/-khɔc' | Source, origin |

| Locative | -rɛ | Spatio-temporal location |

Possession

Santali has possessive suffixes which are only used with kinship terms: 1st person -ɲ, 2nd person -m, 3rd person -t. The suffixes do not distinguish possessor number.[25]

Pronouns

The personal pronouns in Santali distinguish inclusive and exclusive first person and anaphoric and demonstrative third person.[26]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | iɲ | əliɲ | alɛ |

| inclusive | alaŋ | abo | ||

| 2nd person | am | aben | apɛ | |

| 3rd person | Anaphoric | ac' | əkin | ako |

| Demonstrative | uni | unkin | onko | |

The interrogative pronouns have different forms for animate ('who?') and inanimate ('what?'), and referential ('which?') vs. non-referential.[27]

| Animate | Inanimate | |

|---|---|---|

| Referential | ɔkɔe | oka |

| Non-referential | cele | cet' |

The indefinite pronouns are:[28]

| Animate | Inanimate | |

|---|---|---|

| 'any' | jãheã | jãhã |

| 'some' | adɔm | adɔmak |

| 'another' | ɛʈak'ic' | ɛʈak'ak' |

The demonstratives distinguish three degrees of deixis (proximate, distal, remote) and simple ('this', 'that', etc.) and particular ('just this', 'just that') forms.[29]

| Simple | Particular | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animate | Inanimate | Animate | Inanimate | |

| Proximate | nui | noa | nii | niə |

| Distal | uni | ona | ini | inə |

| Remote | həni | hana | hini | hinə |

Numerals

The basic cardinal numbers (transcribed into Latin script IPA)[30] are:

| 1 | ᱢᱤᱫ | mit' |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ᱵᱟᱨ | bar |

| 3 | ᱯᱮ | pɛ |

| 4 | ᱯᱩᱱ | pon |

| 5 | ᱢᱚᱬᱮ | mɔ̃ɽɛ̃ |

| 6 | ᱛᱩᱨᱩᱭ | turui |

| 7 | ᱮᱭᱟᱭ | ɛyae |

| 8 | ᱤᱨᱟᱹᱞ | irəl |

| 9 | ᱟᱨᱮ | arɛ |

| 10 | ᱜᱮᱞ | gɛl |

| 20 | ᱤᱥᱤ | -isi |

| 100 | ᱥᱟᱭ | -sae |

The numerals are used with numeral classifiers. Distributive numerals are formed by reduplicating the first consonant and vowel, e.g. babar 'two each'.

Numbers basically follow a base-10 pattern. Numbers from 11 to 19 are formed by addition, "gel" ('10') followed by the single-digit number (1 through 9). Multiples of ten are formed by multiplication: the single-digit number (2 through 9) is followed by "gel" ('10'). Some numbers are part of a base-20 number system. 20 can be "bar gel" or "isi".

ᱯᱮ

pe

(3

×

ᱜᱮᱞ

gel

10)

or

or

or

(ᱢᱤᱫ)

(mit’)

((1)

×

ᱤᱥᱤ

isi

20

+

ᱜᱮᱞ

gel

10)

30

Verbs

Verbs in Santali inflect for tense, aspect and mood, voice and the person and number of the subject and sometimes of the object.[31]

Subject markers

| singular | dual | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | -ɲ(iɲ) | -liɲ | -lɛ |

| inclusive | -laŋ | -bon | ||

| 2nd person | -m | -ben | -pɛ | |

| 3rd person | -e | -kin | -ko | |

Object markers

Transitive verbs with pronominal objects take infixed object markers.

| singular | dual | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | exclusive | -iɲ- | -liɲ- | -lɛ- |

| inclusive | -laŋ- | -bon- | ||

| 2nd person | -me- | -ben- | -pɛ- | |

| 3rd person | -e- | -kin- | -ko- | |

Syntax

Santali is an SOV language, though topics can be fronted.[32]

Influence on other languages

Borrowing between Santali and other Indian languages has not yet been studied fully. In modern Indian languages, like Western Hindi, the steps of evolution from Midland Prakrit Sauraseni could be traced clearly. In the case of Bengali such steps of evolution are not always clear and distinct, and one has to look at other influences that moulded Bengali's essential characteristics.

A notable work in this field was initiated by linguist Byomkes Chakrabarti in the 1960s. Chakrabarti investigated the complex process of assimilation of Austroasiatic family, particularly Santali elements, into Bengali. He showed the overwhelming influence of Bengali on Santali. His formulations are based on the detailed study of two-way influences on all aspects of both languages and tried to bring out the unique features of the languages. More research is awaited in this area.

Notable linguist Khudiram Das authored the 'Santali Bangla Samashabda Abhidhan' (সাঁওতালি বাংলা সমশব্দ অভিধান), a book focusing on the influence of the Santali language on Bengali and providing a basis for further research on this subject. 'Bangla Santali Bhasha Samparka (বাংলা সান্তালী ভাষা-সম্পর্ক) is a collection of essays in E-book format authored by him and dedicated to linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji on the relationship between the Bengali and Santali languages.

See also

References

- "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Santali at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Mahali at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- "P and AR & e-Governance Dept". wbpar.gov.in. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Redirected". 19 November 2019.

- Santali at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Mahali at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages". censusindia.gov.in. Census of India. 20 May 2013.

- Sidwell, Paul. 2018. Austroasiatic Studies: state of the art in 2018. Archived 22 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Presentation at the Graduate Institute of Linguistics, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan, 22 May 2018.

- Hembram, Phatik Chandra (2002). Santhali, a Natural Language. U. Hembram. p. 165.

- "Ol Chiki (Ol Cemet', Ol, Santali)". Scriptsource.org. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Santali Localization". Andovar.com. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Syllabus for UGC NET Santali, Dec 2013" (PDF). Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Santhali". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Santhali becomes India's first tribal language to get own Wikipedia edition". Hindustan Times. 9 August 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- "SCHEDULED LANGUAGES IN DESCENDING ORDER OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH - 2011" (PDF). census.gov.in. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2011" (PDF). census.gov.in. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "PART-A: DISTRIBUTION OF THE 22 SCHEDULED LANGUAGES-INDIA/STATES/UNION TERRITORIES - 2011 CENSUS" (PDF). census.gov.in. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Second language". India Today. 22 October 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Roy, Anirban (27 May 2011). "West Bengal to have six more languages for official use". India Today. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Glottolog 3.2 – Santali". glottolog.org.

- "Santali: Paharia language". Global recordings network. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- Anderson, Gregory D.S. (2007). The Munda verb: typological perspectives. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 32.

- Ghosh (2008), pp. 32–33.

- Ghosh (2008), pp. 34–38.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 38.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 41.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 43.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 44.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 45.

- "Santali". The Department of Linguistics, Max Planck Institute (Leipzig, Germany). 2001. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Ghosh (2008), p. 53ff..

- Ghosh (2008), p. 74.

Works cited

- Ghosh, Arun (2008). "Santali". In Anderson, Gregory D.S. (ed.). The Munda Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 11–98.

Further reading

- Byomkes Chakrabarti (1992). A comparative study of Santali and Bengali. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 81-7074-128-9

- Hansda, Kali Charan (2015). Fundamental of Santhal Language. Sambalpur.

- Hembram, P. C. (2002). Santali, a natural language. New Delhi: U. Hembram.

- Newberry, J. (2000). North Munda dialects: Mundari, Santali, Bhumia. Victoria, B.C.: J. Newberry. ISBN 0-921599-68-4

- Mitra, P. C. (1988). Santali, the base of world languages. Calcutta: Firma KLM.

- Зограф Г. А. (1960/1990). Языки Южной Азии. М.: Наука (1-е изд., 1960).

- Лекомцев, Ю. K. (1968). Некоторые характерные черты сантальского предложения // Языки Индии, Пакистана, Непала и Цейлона: материалы научной конференции. М: Наука, 311–321.

- Grierson, George A. (1906). Linguistic Survey of India. Vol. IV, Mundā and Dravidian languages. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India.

- Maspero, Henri. (1952). Les langues mounda. Meillet A., Cohen M. (dir.), Les langues du monde, P.: CNRS.

- Neukom, Lukas. (2001). Santali. München: LINCOM Europa.

- Pinnow, Heinz-Jürgen. (1966). A comparative study of the verb in the Munda languages. Zide, Norman H. (ed.) Studies in comparative Austroasiatic linguistics. London—The Hague—Paris: Mouton, 96–193.

- Sakuntala De. (2011). Santali : a linguistic study. Memoir (Anthropological Survey of India). Kolkata: Anthropological Survey of India, Govt. of India.

- Vermeer, Hans J. (1969). Untersuchungen zum Bau zentral-süd-asiatischer Sprachen (ein Beitrag zur Sprachbundfrage). Heidelberg: J. Groos.

- 2006-d. Santali. In E. K. Brown (ed.) Encyclopedia of Languages and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier Press.

Dictionaries

- Bodding, Paul O. (1929). A Santal dictionary. Oslo: J. Dybwad.

- A. R. Campbell (1899). A Santali-English dictionary. Santal Mission Press.

- English-Santali/Santali-English dictionaries

- Macphail, R. M. (1964). An Introduction to Santali, Parts I & II. Benagaria: The Santali Literature Board, Santali Christian Council.

- Minegishi, M., & Murmu, G. (2001). Santali basic lexicon with grammatical notes. Tōkyō: Institute for the Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. ISBN 4-87297-791-2

Grammars and primers

- Bodding, Paul O. 1929/1952. A Santal Grammar for the Beginners, Benagaria: Santal Mission of the Northern Churches (1st edition, 1929).

- Cole, F. T. (1896). Santạli primer. Manbhum: Santal Mission Press.

- Macphail, R. M. (1953) An Introduction to Santali. Firma KLM Private Ltd.

- Muscat, George. (1989) Santali: A New Approach. Sahibganj, Bihar : Santali Book Depot.

- Skrefsrud, Lars Olsen (1873). A Grammar of the Santhal Language. Benares: Medical Hall Press.

- Saren, Jagneswar "Ranakap Santali Ronor" (Progressive Santali Grammar), 1st edition, 2012.

Literature

- Pandit Raghunath Murmu (1925) ronor : Mayurbhanj, Odisha Publisher ASECA, Mayurbhanj

- Bodding, Paul O., (ed.) (1923—1929) Santali Folk Tales. Oslo: Institutet for sammenlingenden kulturforskning, Publikationen. Vol. I—III.

- Campbell, A. (1891). Santal folk tales. Pokhuria, India: Santal Mission Press.

- Murmu, G., & Das, A. K. (1998). Bibliography, Santali literature. Calcutta: Biswajnan. ISBN 81-7525-080-1

- Santali Genesis Translation.

- The Dishom Beura, India's First Santali Daily News Paper. Publisher, Managobinda Beshra, National Correspondent: Mr. Somenath Patnaik