Multiracial Americans

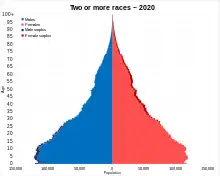

Multiracial Americans or mixed-race Americans are Americans who have mixed ancestry of two or more races. The term may also include Americans of mixed-race ancestry who self-identify with just one group culturally and socially (cf. the one-drop rule). In the 2010 United States census, roughly 9 million individuals or 3.2% of the population, self-identified as multiracial.[3][4] There is evidence that an accounting by genetic ancestry would produce a higher number.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Self-identified multiracial Americans: 10,435,797[1] 3.2% of total U.S. population (2018) According to 2020 census: 33,848,943[2] 10.2% of total U.S. population (2020) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| West: 2.4 million (3.4%) South: 1.8 million (1.6%) Midwest: 1.1 million (1.6%) Northeast: 0.8 million (1.6%) (2006 American Community Survey) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Métis Americans, Louisiana Creoles, Hapas, Melungeons |

The impact of historical racial caste systems, such as that created by admixture between white European colonists and Native Americans, has often led people to identify or be classified by only one ethnicity, generally that of the culture in which they were raised.[5] Prior to the mid-20th century, many people hid their multiracial heritage because of racial discrimination against minorities.[5] While many Americans may be considered multiracial, they often do not know it or do not identify so culturally, any more than they maintain all the differing traditions of a variety of national ancestries.[5]

After a lengthy period of formal racial segregation in the former Confederacy following the Reconstruction Era and bans on interracial marriage in various parts of the country, more people are openly forming interracial unions. In addition, social conditions have changed and many multiracial people do not believe it is socially advantageous to try to "pass" as white. Diverse immigration has brought more mixed race people into the United States, such as a significant population of Hispanics. Since the 1980s, the United States has had a growing multiracial identity movement (cf. Loving Day).[6] Because more Americans have insisted on being allowed to acknowledge their mixed racial origins, the 2000 census for the first time allowed residents to check more than one ethno-racial identity and thereby identify as multiracial. In 2008, Barack Obama was elected as the first biracial President of the United States; he acknowledges both sides of his family and identifies as African-American.[7]

Today, multiracial individuals are found in every corner of the country. Multiracial groups in the United States include many African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Métis Americans, Louisiana Creoles, Hapas, Melungeons and several other communities found primarily in the Eastern US. Many Native Americans are multiracial in ancestry while identifying fully as members of federally recognized tribes.

History

The American people are mostly multi-ethnic descendants of various culturally distinct immigrant groups, many of which have now developed nations. Some consider themselves multiracial, while acknowledging race as a social construct. Creolization, assimilation and integration have been continuing processes. The Civil Rights Movement and other social movements since the mid-twentieth century worked to achieve social justice and equal enforcement of civil rights under the constitution for all ethnicities. In the 2000s, less than 5% of the population identified as multiracial. In many instances, mixed racial ancestry is so far back in an individual's family history (for instance, before the Civil War or earlier), that it does not affect more recent ethnic and cultural identification.

Interracial relationships, common-law marriages and marriages occurred since the earliest colonial years, especially before slavery hardened as a racial caste associated with people of African descent in Colonial America. Several of the Thirteen Colonies passed laws in the 17th century that gave children the social status of their mother, according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, regardless of the father's race or citizenship. This overturned the precedent in common law by which a man gave his status to his children – this had enabled communities to demand that fathers support their children, whether legitimate or not. The change increased white men's ability to use slave women sexually, as they had no responsibility for the children. As master as well as father of mixed-race children born into slavery, the men could use these people as servants or laborers or sell them as slaves. In some cases, white fathers provided for their multiracial children, paying or arranging for education or apprenticeships and freeing them, particularly during the two decades following the Revolutionary War. (The practice of providing for the children was more common in French and Spanish colonies, where a class of free people of color developed who became educated and property owners.) Many other white fathers abandoned the mixed race children and their mothers to slavery.

The researcher Paul Heinegg found that most families of free people of color in colonial times were founded from the unions of white women, whether free or indentured servants and African men, slave, indentured or free.[8] In the early years, the working-class peoples lived and worked together. Their children were free because of the status of the white women. This was in contrast to the pattern in the post-Revolutionary era, in which most mixed-race children had white fathers and Black mothers.[8]

Anti-miscegenation laws were passed in most states during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, but this did not prevent white slaveholders, their sons, or other powerful white men from taking slave women as concubines and having multiracial children with them. In California and the rest of the American West, there were greater numbers of Latin American and Asian residents. These were prohibited from official relationships with whites. White legislators passed laws prohibiting marriage between European and Asian Americans until the 1950s.

Early United States history

Interracial relationships have had a long history in North America and the United States, beginning with the intermixing of European explorers and soldiers, who took native women as companions. After European settlement increased, traders and fur trappers often married or had unions with women of native tribes. In the 17th century, faced with a continuing, critical labor shortage, colonists primarily in the Chesapeake Bay Colony, imported Africans as laborers, sometimes as indentured servants and, increasingly, as slaves. African slaves were also imported into New York and other northern ports by European colonists. Some African slaves were freed by their masters during these early years.

In the colonial years, while conditions were more fluid, white women, indentured servant or free, and African men, servant, slave or free, made unions. Because the women were free, their mixed-race children were born free; they and their descendants formed most of the families of free people of color during the colonial period in Virginia. The scholar Paul Heinegg found that eighty percent of the free people of color in North Carolina in censuses from 1790 to 1810 could be traced to families free in Virginia in colonial years.[9]

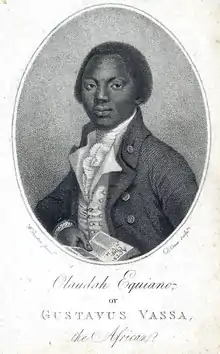

In 1789, Olaudah Equiano, a former slave from modern-day Nigeria who was enslaved in North America, published his autobiography. He advocated interracial marriage between whites and blacks.[10] By the late eighteenth century, visitors to the Upper South noted the high proportion of mixed-race slaves, evidence of miscegenation by white men.

In 1790, the first federal population census was taken in the United States. Enumerators were instructed to classify free residents as white or "other." Only the heads of households were identified by name in the federal census until 1850. Native Americans were included among "Other;" in later censuses, they were included as "Free people of color" if they were not living on Indian reservations. Slaves were counted separately from free persons in all the censuses until the Civil War and end of slavery. In later censuses, people of African descent were classified by appearance as mulatto (which recognized visible European ancestry in addition to African) or black.

After the American Revolutionary War, the number and proportion of free people of color increased markedly in the North and the South as slaves were freed. Most northern states abolished slavery, sometimes, like New York, in programs of gradual emancipation that took more than two decades to be completed. The last slaves in New York were not freed until 1827. In connection with the Second Great Awakening, Quaker and Methodist preachers in the South urged slaveholders to free their slaves. Revolutionary ideals led many men to free their slaves, some by deed and others by will, so that from 1782 to 1810, the percentage of free people of color rose from less than one percent to nearly 10 percent of blacks in the South.[11]

19th century: American Civil War, emancipation, Reconstruction and Jim Crow

Of numerous relationships between male slaveholders, overseers, or master's sons and women slaves, the most notable is likely that of President Thomas Jefferson with his slave Sally Hemings. As noted in the 2012 collaborative Smithsonian-Monticello exhibit, Slavery at Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty, Jefferson, then a widower, took Hemings as his concubine for nearly 40 years. They had six children of record; four Hemings children survived into adulthood, and he freed them all, among the very few slaves he freed. Two were allowed to "escape" to the North in 1822, and two were granted freedom by his will upon his death in 1826. Seven-eighths white by ancestry, all four of his Hemings children moved to northern states as adults; three of the four entered the white community, and all their descendants identified as white. Of the descendants of Madison Hemings who continued to identify as black, some in future generations eventually identified as white and "married out," while others continued to identify as African American. It was socially advantageous for the Hemings children to identify as white, in keeping with their appearance and the majority proportion of their ancestry. Although born into slavery, the Hemings children were legally white under Virginia law of the time.

20th century

Racial discrimination continued to be enacted in new laws in the 20th century, for instance the one-drop rule was enacted in Virginia's 1924 Racial Integrity Law and in other southern states, in part influenced by the popularity of eugenics and ideas of racial purity. People buried fading memories that many whites had multiracial ancestry. Many families were multiracial. Similar laws had been proposed but not passed in the late nineteenth century in South Carolina and Virginia, for instance. After regaining political power in Southern states by disenfranchising blacks, white Democrats passed laws to impose Jim Crow and racial segregation to restore white supremacy. They maintained these until forced to change in the 1960s and after by enforcement of federal legislation authorizing oversight of practices to protect the constitutional rights of African Americans and other minority citizens.

In 1967 the United States Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia ruled that anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional.[12]

In the twentieth century up until 1989, social service organizations typically assigned multiracial children to the racial identity of the minority parent, which reflected social practices of hypodescent.[13] Black social workers had influenced court decisions on regulations related to identity; they argued that, as the biracial child was socially considered black, it should be classified that way in order to identify with the group and learn to deal with discrimination.[14]

By 1990, the Census Bureau included more than a dozen ethnic/racial categories on the census, reflecting not only changing social ideas about ethnicity, but the wide variety of immigrants who had come to reside in the United States due to changing historical forces and new immigration laws in the 1960s. With a changing society, more citizens have begun to press for acknowledging multiracial ancestry. The Census Bureau changed its data collection by allowing people to self-identify as more than one ethnicity. Some ethnic groups are concerned about the potential political and economic effects, as federal assistance to historically underserved groups has depended on Census data. According to the Census Bureau, as of 2002, 75% of all African Americans had multiracial ancestries.[15]

The proportion of acknowledged multiracial children in the United States is growing. Interracial partnerships are on the rise, as are transracial adoptions. In 1990, around 14% of 18- to 19-year-olds, 12% of 20- to 21-year-olds, and 7% of 34- to 35-year-olds were involved in interracial relationships (Joyner and Kao, 2005).[16]

Demographics

Multiracial people who wanted to acknowledge their full heritage won a victory of sorts in 1997, when the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) changed the federal regulation of racial categories to permit multiple responses. This resulted in a change to the 2000 United States Census, which allowed participants to select more than one of the six available categories, which were, in brief: "White," "Black or African-American," "Asian," "American Indian or Alaskan Native," "Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander" and "Other." Further details are given in the article: Race and ethnicity in the United States Census. The OMB made its directive mandatory for all government forms by 2003.

In 2000, Cindy Rodriguez reported on reactions to the new census:[17]

To many mainline civil rights groups, the new census is part of a multiracial nightmare. After decades of framing racial issues in stark black and white terms, they fear that the multiracial movement will break down longstanding alliances, weakening people of color by splintering them into new subgroups.

Some multiracial individuals feel marginalized by U.S. society. For example, when applying to schools or for a job or when taking standardized tests, Americans are sometimes asked to check boxes corresponding to race or ethnicity. Typically, about five race choices are given, with the instruction to "check only one." While some surveys offer an "other" box, this choice groups together individuals of many different multiracial types (ex: European Americans/African-Americans are grouped with Asian/Native American Indians).

The 2000 U.S. Census in the write-in response category had a code listing which standardizes the placement of various write-in responses for automatic placement within the framework of the U.S. Census's enumerated races. Whereas most responses can be distinguished as falling into one of the five enumerated races, there remains some write-in responses which fall into the "Mixture" heading which cannot be racially categorized. These include "Bi Racial, Combination, Everything, Many, Mixed, Multi National, Multiple, Several and Various".[18]

In 1997, Greg Mayeda, a member of the Board of Directors person for the Hapa Issues Forum, attended a meeting regarding the new racial classifications for the 2000 U.S. Census. He was arguing against a multiracial category and for multiracial people being counted as all of their races. He argued that a

separate Multiracial Box does not allow a person who identifies as mixed race the opportunity to be counted accurately. After all, we are not just mixed race. We are representatives of all racial groups and should be counted as such. A stand alone Multiracial Box reveals very little about the person's background checking it.[19]

According to James P. Allen and Eugene Turner from California State University, Northridge, who analyzed the 2000 Census, most multiracial people identified as part white. In addition, the breakdown is as follows:

- white/Native American and Alaskan Native, at 7,015,017,

- white/black at 737,492,

- white/Asian at 727,197, and

- white/Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander at 125,628.[20]

In 2010, 1.6 million Americans checked both "black" and "white" on their census forms, a figure 134% higher than the number a decade earlier.[21] The number of interracial marriages and relationships, and transracial and international adoptions has increased the proportion of multiracial families.[22] In addition, more individuals may be identifying multiple ancestries, as the concept is more widely accepted.

Multiracial American identity

Political history

Despite a long history of miscegenation within the U.S. political territory and American continental landscape, advocacy for a unique social race classification to recognize direct, or recent, multiracial parentage did not begin until the 1970s. After the Civil Rights Era and rapid integration of African-Americans into predominately European-American institutions and residential communities, it became more socially acceptable for White-identified women to date, marry and procreate children fathered by non-White men. This trend evolved a political push that offspring of interracial unions fully inherit the social race classifications of both parents, regardless of the racial classification of the maternal parent. This advocacy countered what had been practiced in the United States since the early 1800s where a newborn's racial classification defaulted to that of their mother, which was by a variety of classifications differing from state to state over the past two centuries. In some states 3/4ths African ancestry determined African identity, in some it was more qualified, or less. The hypodescent or one-drop rule, meaning one African ancestor identified as black was adopted by Virginia in 1924. This one-drop rule was not adopted as law by South Carolina, Louisiana and other states where Creole were or had been slaveowners. White supremacist in effect practicing the one-drop rule during chattel slavery, the rule delegated the racial classification of offspring produced by White male slave masters and female slaves to be slaves, failing to acknowledge the male parentage. Similarly laws were passed punishing free people of mixed heritage, the same as free black men and women, denying their basic rights. Voting, for example, which free blacks could and did do under French rule, were denied after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 within a few years time. About ten percent of the slave population, according to observers, looked to be white, but had known African ancestors. After the end of slavery most of these people disappeared into the white population simply by moving. Walter White, President of the NAACP in 1920 reported that passing for white from 1880 to 1920 involved about 400,000 descendents of slaves. See Helen Catterall, editor, Judicial Cases Concerning American Slavery and the Negro, 5 Volumes, 1935 and A Man Called White, autobiography by Walter White, first President of NAACP.

Contemporary interracial marriage

In 2009, Keith Bardwell, a justice of the peace in Robert, Louisiana, refused to officiate a wedding for an interracial couple and was summarily sued in federal court. See refusal of interracial marriage in Louisiana.

About 15% of all new marriages in the United States in 2010 were between spouses of a different race or ethnicity from one another, more than double the share in 1980 (6.7%).[23]

Multiracial families and identity issues

Given the variety of the familial and general social environments in which multiracial children are raised, along with the diversity of their appearance and heritage, generalizations about multiracial children's challenges or opportunities are not very useful. A 1989 article written by Charlotte Nitary revealed that parents of mixed raced children often struggled between teaching their children to identify as only the race of their non-white parent, not identifying with social race at all, or identifying with the racial identities of both parents.[24]

The social identity of children and of their parents in the same multiracial family may vary or be the same.[25] Some multiracial children feel pressure from various sources to "choose" or to identify as a single racial identity. Others may feel pressure not to abandon one or more of their ethnicities, particularly if identified with culturally.

Some children grow up without race being a significant issue in their lives because they identify against the one-drop-rule construct. [26] This approach to addressing plural racial heritage is something U.S. society has slowly become socialized into as the general consensus among monoracially identified individuals is plural racial identity is a choice and presents disingenuous motives against the more oppressed inherited racial identity.[27] By the 1990s, as more multiracial identified students attended colleges and university, many were met with alienation from culturally and racially homogenous groups on campus. This common national trend saw the launch of many multi-racial campus organizations across the country. By the 2000s, these efforts for self-identification soon reached beyond educational institutions and into mainstream society.[28]

In her book Love's Revolution: Interracial Marriage, Maria P. P. Root suggests that when interracial parents divorce, their mixed-race children become threatening in circumstances where the custodial parent has remarried into a union where an emphasis is placed on racial identity.[29]

Some multiracial individuals attempt to claim a new category. For instance, the athlete Tiger Woods has said that he is not only African-American but "Cablinasian," as he is of Caucasian, African-American, Native American and Asian descent.[30]

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Keanu Reeves has an English mother and a father of English, Hawaiian, Irish, Portuguese and Chinese descent.[34][35][36]

Keanu Reeves has an English mother and a father of English, Hawaiian, Irish, Portuguese and Chinese descent.[34][35][36] Charles Mingus was born to a mother of English and Chinese descent and a father of African-American and Swedish descent.[37][38]

Charles Mingus was born to a mother of English and Chinese descent and a father of African-American and Swedish descent.[37][38]

Jennifer Beals was born to an Irish-American mother and an African-American father.[39]

Jennifer Beals was born to an Irish-American mother and an African-American father.[39] Kamala Harris was born in Oakland, California to a Tamil Indian mother[40] and an Afro-Jamaican father.[41]

Kamala Harris was born in Oakland, California to a Tamil Indian mother[40] and an Afro-Jamaican father.[41] Tiger Woods was born to an Asian-American mother and African-American father.

Tiger Woods was born to an Asian-American mother and African-American father.

Native American identity

In the 2010 Census, nearly 3 million people indicated that their race was Native American (including Alaska Native).[47] Of these, more than 27% specifically indicated "Cherokee" as their ethnic origin.[48][49] Many of the First Families of Virginia claim descent from Pocahontas or some other "Indian princess". This phenomenon has been dubbed the "Cherokee Syndrome".[50] Across the US, numerous individuals cultivate an opportunistic ethnic identity as Native American, sometimes through Cherokee heritage groups or Indian Wedding Blessings.[51]

Levels of Native American ancestry (distinct from Native American identity) differ. The genomes of self-reported African Americans averaged to 0.8% Native American ancestry, those of European Americans averaged to 0.18%, and those of Latinos averaged to 18.0%.[52][53]

Many tribes, especially those in the Eastern United States, are primarily made up of individuals with an unambiguous Native American identity, despite being predominantly of European ancestry.[51] Point in case, more than 75% of those enrolled in the Cherokee Nation have less than one-quarter Cherokee blood[54] and the current Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Bill John Baker, is 1/32 Cherokee, amounting to about 3%.

Historically, non-Native governments have forced numerous Native Americans to assimilate into colonial and later American society, e.g. through language shifts and conversions to Christianity. In many cases, this process occurred through forced assimilation of children sent off to special boarding schools far from their families. Those who could pass for white had the advantage of white privilege.[51] Today, after generations of racial whitening through hypergamy, a number of Native Americans may have fair skin like White Americans. Native Americans are more likely than any other racial group to practice racial exogamy, resulting in an ever-declining proportion of indigenous blood among those who claim a Native American identity.[55] Some tribes disenroll tribal members unable to provide proof of Native ancestry, usually through a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood. Disenrollment has become a contentious issue in Native American reservation politics.[56][57]

Bill John Baker, who is 3.13% Cherokee,[58] was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 2011 to 2019.

Bill John Baker, who is 3.13% Cherokee,[58] was the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation from 2011 to 2019. Seminole elder Billy Bowlegs III was also of Muscogee, African-American and Scottish descent through his maternal grandfather Osceola.[59]

Seminole elder Billy Bowlegs III was also of Muscogee, African-American and Scottish descent through his maternal grandfather Osceola.[59]

Charles Curtis was a Native American, born to a Kaw, Osage, a Potawatomi and French mother and an English, Scots and Welsh father.[61]

Charles Curtis was a Native American, born to a Kaw, Osage, a Potawatomi and French mother and an English, Scots and Welsh father.[61] Deb Haaland is from the Laguna Pueblo people and is the first Native American Cabinet Secretary as Secretary of Interior. Her father is Norwegian-American.[62]

Deb Haaland is from the Laguna Pueblo people and is the first Native American Cabinet Secretary as Secretary of Interior. Her father is Norwegian-American.[62]

Native American lineage and admixture in Black and African-Americans

Jimi Hendrix was born to a Cherokee mother and was part English, African-American, Irish and German.[64][65][66]

Jimi Hendrix was born to a Cherokee mother and was part English, African-American, Irish and German.[64][65][66]

.jpg.webp) James Earl Jones has said in interviews that his parents were both of mixed African-American, Irish and Native American ancestry.

James Earl Jones has said in interviews that his parents were both of mixed African-American, Irish and Native American ancestry.

Interracial relations between Native Americans and African-Americans is a part of American history that has been neglected.[74] The earliest record of African and Native American relations in the Americas occurred in April 1502, when the first Africans kidnapped were brought to Hispaniola to serve as slaves. Some escaped and somewhere inland on Santo Domingo, the first Black Indians were born.[75] In addition, an example of African slaves' escaping from European colonists and being absorbed by Native Americans occurred as far back as 1526. In June of that year, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón established a Spanish colony near the mouth of the Pee Dee River in what is now eastern South Carolina. The Spanish settlement was named San Miguel de Gualdape. Amongst the settlement were 100 enslaved Africans. In 1526, the first African slaves fled the colony and took refuge with local Native Americans.[76]

European colonists created treaties with Native American tribes requesting the return of any runaway slaves. For example, in 1726, the governor of New York exacted a promise from the Iroquois to return all runaway slaves who had joined them. This same promise was extracted from the Huron people in 1764, and from the Delaware people in 1765, though there is no record of slaves ever being returned.[77] Numerous advertisements requested the return of African-Americans who had married Native Americans or who spoke a Native American language. The primary exposure that Native Americans and Africans had to each other came through the institution of slavery.[78] Native Americans learned that Africans had what Native Americans considered 'Great Medicine' in their bodies because Africans were virtually immune to the Old-World diseases that were decimating most native populations.[79] Because of this, many tribes encouraged marriage between the two groups, to create stronger, healthier children from the unions.[79]

For African-Americans, the one-drop rule was a significant factor in ethnic solidarity. African-Americans generally shared a common cause in society regardless of their multiracial admixture or social/economic stratification. Additionally, African-Americans found it, near, impossible to learn about their Native American heritage as many family elders withheld pertinent genealogical information.[74] Tracing the genealogy of African-Americans can be a very difficult process, especially for descendants of Native Americans, because African-Americans who were slaves were forbidden to learn to read and write and a majority of Native Americans neither spoke English, nor read or wrote it.[74]

Native American lineage and admixture in White and European-Americans

Ben Campbell was born to an Azorian mother and father of Northern Cheyenne, Apache and Pueblo Indian descent.[80]

Ben Campbell was born to an Azorian mother and father of Northern Cheyenne, Apache and Pueblo Indian descent.[80]_of_Faunceway_Baptiste_or_Battice_(Mixed_Blood)_1868.jpg.webp) Faunceway Baptiste was a multi-racial Native American of Choctaw and Euro-American heritage. He was a lieutenant colonel in the Civil War.

Faunceway Baptiste was a multi-racial Native American of Choctaw and Euro-American heritage. He was a lieutenant colonel in the Civil War.

Ruth Gordon's ancestor Parthena was an African mistress of Joseph Pendarvis a member of the notable, Native American descended, Landgrave family of South Carolina.[81][82]

Ruth Gordon's ancestor Parthena was an African mistress of Joseph Pendarvis a member of the notable, Native American descended, Landgrave family of South Carolina.[81][82]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Interracial relations among Native Americans and Europeans occurred from the earliest years of colonization. European impact was immediate, widespread and profound—more than any other race that had contact with Native Americans during the early years of colonization and nationhood.[85]

Some early male settlers married Native American women or had informal unions with them. Early contact between Native Americans and Europeans was often charged with tension, but also had moments of friendship, cooperation and intimacy.[86] Several marriages took place in European colonies between European men and Native women. For instance, on April 5, 1614, Pocahontas, a Powhatan woman in present-day Virginia, married the Virginian colonist John Rolfe of Jamestown. Their son Thomas Rolfe was an ancestor to many descendants in First Families of Virginia. As a result, discrimanatory laws (such as those against African Americans) often excluded Native Americans during this period. In the early 19th century, the Native American woman Sacagawea, who would help translate for and guide the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the West, married the French-Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau.

Some Europeans living among Native Americans were called "White Indians". They "lived in native communities for years, learned native languages fluently, attended native councils, and often fought alongside their native companions."[87] European traders and trappers often married Native American women from tribes on the frontier and had families with them. Sometimes these marriages were done for political reasons between a Native American tribe and the European traders. Some traders, who kept bases in the cities, had what were called "country wives" among Native Americans, with legal European-American wives and children at home in the city. Not all abandoned their "natural" mixed-race children. Some arranged for sons to be sent to European-American schools for their education. Early European colonists were predominately men and Native American women were at risk for rape or sexual harassment especially if they were enslaved.[88]

Most marriages between Europeans and Native Americans were between European men and Native American women. The social identity of the children was strongly determined by the tribe's kinship system. This determined how easy it would be for the child assimilated into the tribe. Among the matrilineal tribes of the Southeast, such as the Creek and Cherokee, the mixed race children generally were accepted as and identified as Indian, as they gained their social status from their mother's clans and tribes and often grew up with their mothers and their male relatives. By contrast, among the patrilineal Omaha, for example, the child of a white man and Omaha woman was considered "white"; such mixed-race children and their mothers would be protected, but the children could formally belong to the tribe as members only if adopted by a man.

In those years, a Native American man had to get consent of the European parents in order to marry a white woman. When such marriages were approved, it was with the stipulation that "he can prove to support her as a white woman in a good home".[89]

In the early twentieth century in the West, "intermarried whites" were listed in a separate category on the Dawes Rolls, when members of tribes were listed and identified for allocation of lands to individual heads of households in the break-up of tribal communal lands in Indian Territory. This increased intermarriage as some white men married Native Americans to gain control of land. In the late 19th century, three European-American middle-class female teachers married Native American men they had met at Hampton Institute during the years when it ran its Indian program.[90] In the late nineteenth century, Charles Eastman, a physician of Sioux and European ancestry who trained at Boston University, married Elaine Goodale, a European-American woman from New England. They met and worked together in Dakota Territory when she was Superintendent of Indian Education and he was a doctor for the reservations. His maternal grandfather was Seth Eastman, an artist and Army officer from New England, who had married a Sioux woman and had a daughter with her while stationed at Fort Snelling in Minnesota.

Black and African-American identity

Americans with sub-Saharan African ancestry for historical reasons: slavery, partus sequitur ventrem, one-eighth law, the one-drop rule of 20th-century legislation, have frequently been classified as black (historically) or African-American, even if they have significant European-American or Native American ancestry. As slavery became a racial caste, those who were enslaved and others of any African ancestry were classified by what is termed "hypodescent" according to the lower status ethnic group. Many of majority European ancestry and appearance "married white" and assimilated into white society for its social and economic advantages, such as generations of families identified as Melungeons, now generally classified as white but demonstrated genetically to be of European and sub-Saharan African ancestry.

Sometimes people of mixed Native American and African-American descent report having had elder family members withholding pertinent genealogical information.[74] Tracing the genealogy of African-Americans can be a very difficult process, as censuses did not identify slaves by name before the American Civil War, meaning that most African Americans did not appear by name in those records. In addition, many white fathers who used slave women sexually, even those in long-term relationships like Thomas Jefferson's with Sally Hemings, did not acknowledge their mixed race slave children in records, so paternity was lost.

Colonial records of French and Spanish slave ships and sales and plantation records in all the former colonies, often have much more information about slaves, from which researchers are reconstructing slave family histories. Genealogists have begun to find plantation records, court records, land deeds and other sources to trace African-American families and individuals before 1870. As slaves were generally forbidden to learn to read and write, black families passed along oral histories, which have had great persistence. Similarly, Native Americans did not generally learn to read and write English, although some did in the nineteenth century.[74] Until 1930, census enumerators used the terms free people of color and mulatto to classify people of apparent mixed race. When those terms were dropped, as a result of the lobbying by the Southern Congressional bloc, the Census Bureau used only the binary classifications of black or white, as was typical in segregated southern states.

In the 1980s, parents of mixed race children began to organize and lobby for the addition of a more inclusive term of racial designation that would reflect the heritage of their children. When the U.S. government proposed the addition of the category of "biracial" or "multiracial" in 1988, the response from the public was mostly negative. Some African-American organizations and African-American political leaders, such as Congresswoman Diane Watson and Congressman Augustus Hawkins, were particularly vocal in their rejection of the category, as they feared the loss of political and economic power if African-Americans reduced their numbers by self-identification.[91]

Since the 1990s and 2000s, the terms mixed race, multiracial and biracial have been used more frequently in society. It is still most common in the United States (unlike some other countries with a history of slavery) for people seen as "African" in appearance to identify as or be classified solely as "Black" or "African-Americans", for cultural, social and familial reasons.

President Barack Obama is of European-American and East African ancestry; he identifies as African-American.[92] A 2007 poll, when Obama was a presidential candidate, found that Americans differed in their responses as to how they classified him: a majority of White and Hispanics classified him as biracial, but a majority of African-Americans classified him as black.[93]

A 2003 study found an average of 18.6% (±1.5%) European admixture in a population sample of 416 African-Americans from Washington, D.C.[94] Studies of other populations in other areas have found differing percentages of ethnicity.

Twenty percent of African-Americans have more than 25% European ancestry, reflecting the long history of unions between the groups. The "mostly African" group is substantially African, as 70% of African-Americans in this group have less than 15% European ancestry. The 20% of African Americans in the "mostly mixed" group (2.7% of US population) have between 25% and 50% European ancestry.[95]

The writer Sherrel W. Stewart's assertion that "most" African-Americans have significant Native American heritage,[96] is not supported by genetic researchers who have done extensive population mapping studies. The TV series on African-American ancestry, hosted by the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., had genetics scholars who discussed in detail the variety of ancestries among African-Americans. They noted there is popular belief in a high rate of Native American admixture that is not supported by the data that has been collected.

Genetic testing of direct male and female lines evaluates only direct male and female descent without accounting for many ancestors.[97] For this reason, individuals on the Gates show had fuller DNA testing.

The critic Troy Duster, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, thought Gates' series African American Lives should have told people more about the limitations of genetic SNP testing. He says that not all ancestry may show up in the tests, especially for those who claim part-Native American descent.[97][98] Other experts also agree.[99]

Population testing is still being done. Some Native American groups that have been sampled may not have shared the pattern of markers being searched for. Geneticists acknowledge that DNA testing cannot yet distinguish among members of differing cultural Native American nations. There is genetic evidence for three major migrations into North America, but not for more recent historic differentiation.[98] In addition, not all Native Americans have been tested, so scientists do not know for sure that Native Americans have only the genetic markers they have identified.[97][98]

Admixture

On census forms, the government depends on individuals' self-identification. Contemporary African-Americans possess varying degrees of admixture with European (and other) ancestry. They also have various degrees of Native American ancestry.[100][101] In addition to being found to have 8% Asian and 19.6% European ancestry, African-Americans, who were sampled in 2010, were found to be 72.5% African; the Asian ancestry serving as a proxy for Native-American.[102]

Many free African-American families descended from unions between white women and African men in colonial Virginia. Their free descendants migrated to the frontier of Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina in the 18th and 19th centuries. There were also similar free families in Delaware and Maryland, as documented by Paul Heinegg.[103]

In addition, many Native American women turned to African-American men due to the decline in the number of Native American men due to disease and warfare.[85] Some Native American women bought African slaves but, unknown to European sellers, the women freed the African men and married them into their respective tribes.[85] If an African-American man had children by a Native American woman, their children were free because of the status of the mother.[85]

In their attempt to ensure white supremacy decades after emancipation, in the early 20th century, most southern states created laws based on the one-drop rule, defining as black persons with any known African ancestry. This was a stricter interpretation than what had prevailed in the 19th century; it ignored the many mixed families in the state and went against commonly accepted social rules of judging a person by appearance and association. Some courts called it "the traceable amount rule." Anthropologists called it an example of a hypodescent rule, meaning that racially mixed persons were assigned the status of the socially subordinate group.

Prior to the one-drop rule, different states had different laws regarding color. More importantly, social acceptance often played a bigger role in how a person was perceived and how identity was construed than any law. In frontier areas, there were fewer questions about origins. The community looked at how people performed, whether they served in the militia and voted, which were the responsibilities and signs of free citizens. When questions about racial identity arose because of inheritance issues, for instance, litigation outcomes often were based on how people were accepted by neighbors.[104]

The first year in which the U.S. Census dropped the mulatto category was 1920; that year enumerators were instructed to classify people in a binary way as white or black. This was a result of the Southern-dominated Congress convincing the Census Bureau to change its rules.[105][106]

After the Civil War, racial segregation forced African Americans to share more of a common lot in society than they might have given widely varying ancestry, educational and economic levels. The binary division altered the separate status of the traditionally free people of color in Louisiana, for instance, although they maintained a strong Louisiana Créole culture related to French culture and language, and practice of Catholicism. African Americans began to create common cause—regardless of their multiracial admixture or social and economic stratification. In 20th-century changes, during the rise of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, the African-American community increased its own pressure for people of any portion of African descent to be claimed by the black community to add to its power.

By the 1980s, parents of mixed race children (and adults of mixed race ancestry) began to organize and lobby for the ability to show more than one ethnic category on Census and other legal forms. They refused to be put into just one category. When the U.S. government proposed the addition of the category of "biracial" or "multiracial" in 1988, the response from the general public was mostly negative. Some African-American organizations and political leaders, such as Senator Diane Watson and Representative Augustus Hawkins, were particularly vocal in their rejection of the category. They feared a loss in political and economic power if African-Americans abandoned their one category.

This reaction is characterized as "historical irony" by Reginald Daniel (2002). The African-American self-designation had been a response to the one-drop rule, but then people resisted the chance to claim their multiple heritages. At the bottom was a desire not to lose political power of the larger group. Whereas before people resisted being characterized as one group regardless of ranges of ancestry, now some of their own were trying to keep them in the same group.[91]

Definition of African-American

Since the late twentieth century, the number of African and Caribbean ethnic African immigrants have increased in the United States. Together with publicity about the ancestry of President Barack Obama, whose father was from Kenya, some black writers have argued that new terms are needed for recent immigrants. There is a consensus that suggests that the term African-American should refer strictly to the descendants of American Colonial Era chattel slave descendants which includes various, subsequent, Free People of Color ethnic groups who survived the Chattel Slavery Era in the United States.[116] It's been recognized that grouping together all Afrodescent ethnicities, regardless of their unique ancestral circumstances, would deny the lingering effects of slavery within the American Colonial Era chattel slave descended community.[116] A growing sentiment within the Descendants of American Colonial Era Chattel Slaves (DOS) population insists that ethnic African immigrants as well as all other Afro-descent and Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade descendants and those relegated, or self-designated, to the Black race social identity or classification recognize their own unique familial, genealogical, ancestral, social, political and cultural backgrounds.[116]

Stanley Crouch wrote in a New York Daily News piece "Obama's mother is of white U.S. stock. His father is a black Kenyan," in a column entitled "What Obama Isn't: Black Like Me." During the 2008 campaign, the mixed-race columnist David Ehrenstein of the LA Times accused white liberals of flocking to Obama because he was a "Magic Negro", a term that refers to a black person with no past who simply appears to assist the mainstream white (as cultural protagonists/drivers) agenda.[117] Ehrenstein went on to say "He's there to assuage white 'guilt' they feel over the role of slavery and racial segregation in American history."[117]

Reacting to media criticism of Michelle Obama during the 2008 presidential election, Charles Steele Jr., CEO of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference said, "Why are they attacking Michelle Obama and not really attacking, to that degree, her husband? Because he has no slave blood in him."[118] He later claimed his comment was intended to be "provocative" but declined to expand on the subject.[118] Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (who was famously mistaken for a "recent American immigrant" by French President Nicolas Sarkozy[119]), said "descendants of slaves did not get much of a head start, and I think you continue to see some of the effects of that." She has also rejected an immigrant designation for African-Americans and instead prefers the terms black or white.[120]

White and European-American identity

Some of the most notable families include the Van Salees,[81] Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Blacks,[121] Cheswells,[122] Newells,[123] Battises,[124] Bostons,[125] Eldings[126] of the North; the Staffords,[127] Gibsons,[128] Locklears, Pendarvises,[82] Driggers,[129][130] Galphins,[131] Fairfaxes,[132] Grinsteads (Greenstead, Grinsted and Grimsted),[133] Johnsons, Timrods, Darnalls of the South and the Picos,[134] Yturrias[135] and Bushes of the West.[136]

DNA analysis shows varied results regarding non-European ancestry in self-identified White Americans. A 2003 DNA analysis found that about 30% of self-identified White Americans have less than 90% European ancestry.[137] A 2014 study performed on data obtained from 23andme customers found that the percentage of African or American Indian ancestry among White Americans varies significantly by region, with about 5% of White Americans living in Louisiana and South Carolina having 2% or more African ancestry.[138]

Some biographical accounts include the autobiography Life on the Color Line: The True Story of a White Boy Who Discovered He Was Black by Gregory Howard Williams; One Drop: My Father's Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets written by Bliss Broyard about her father Anatole Broyard; the documentary Colored White Boy[139] about a white man in North Carolina who discovers that he is the descendant of a white plantation owner and a raped African slave and the documentary on The Sanders Women[140] of Shreveport, Louisiana.

George Herriman, who was born into a Creole family, wore a hat to conceal his hair texture. His death certificate identified him as Caucasian.[141]

George Herriman, who was born into a Creole family, wore a hat to conceal his hair texture. His death certificate identified him as Caucasian.[141] Patrick Francis Healy was born to an Irish-American plantation owner and his biracial slave. He and his siblings identified as white in their formative years and most made careers in the Catholic Church in the North.[142]

Patrick Francis Healy was born to an Irish-American plantation owner and his biracial slave. He and his siblings identified as white in their formative years and most made careers in the Catholic Church in the North.[142] Carol Channing was born to a white mother and a half African-American and German father. She passed for white during the height of her career and later publicly acknowledged her mixed race origins.[143][144]

Carol Channing was born to a white mother and a half African-American and German father. She passed for white during the height of her career and later publicly acknowledged her mixed race origins.[143][144] Mary Ellen Pleasant, born to a slave and the youngest son of James Pleasants, contributed to advancing the abolitionist movement.

Mary Ellen Pleasant, born to a slave and the youngest son of James Pleasants, contributed to advancing the abolitionist movement.

Racial passing and ambiguity

Passing is a phenomenon most widely noted in the United States, which occurs when a person who may be literally classified as a member of one racial group (by law or frequent social convention applied to others with similar ancestry) is accepted or perceived ("passes") as a member of another.

The phenomenon known as "passing as white" is difficult to explain in other countries or to foreign students. Typical questions are: "Shouldn't Americans say that a person who is passing as white is white or nearly all white and has previously been passing as black?" or "To be consistent, shouldn't you say that someone who is one-eighth white is passing as black?" ... A person who is one-fourth or less American Indian or Korean or Filipino is not regarded as passing if he or she intermarries with and joins fully the life of the dominant community, so the minority ancestry need not be hidden... It is often suggested that the key reason for this is that the physical differences between these other groups and whites are less pronounced than the physical differences between African blacks and whites and therefore are less threatening to whites... [W]hen ancestry in one of these racial minority groups does not exceed one-fourth, a person is not defined solely as a member of that group.[145]

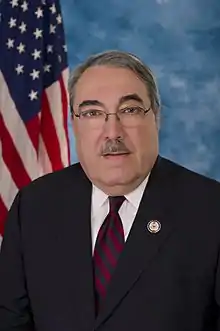

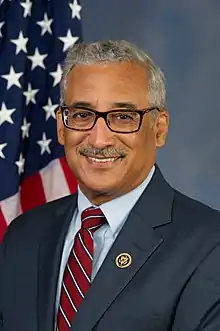

G. K. Butterfield was born to two mixed race black identified parents of Portuguese and African descent from the Azores.[146]

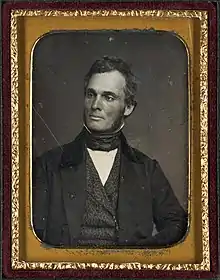

G. K. Butterfield was born to two mixed race black identified parents of Portuguese and African descent from the Azores.[146] Robert Purvis was born to a part Moorish, German Jewish and Sephardic Jewish free woman of color and an English father. He identified as black and worked to serve his community.[147][148][149]

Robert Purvis was born to a part Moorish, German Jewish and Sephardic Jewish free woman of color and an English father. He identified as black and worked to serve his community.[147][148][149]_trailer_8.jpg.webp) Imitation of Life star Fredi Washington portrayed a woman who passed in the famous film, but was against passing in her own life.[150]

Imitation of Life star Fredi Washington portrayed a woman who passed in the famous film, but was against passing in her own life.[150] Walter Francis White belonged to a middle-class hyperdescent African-American chattel slave descended family who remained negro or black-identified.

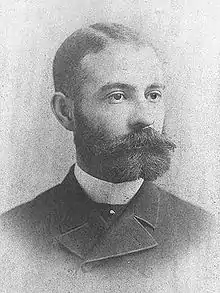

Walter Francis White belonged to a middle-class hyperdescent African-American chattel slave descended family who remained negro or black-identified. Daniel Hale Williams was of African-American and Scots-Irish ancestry. Although members of his family passed as white, he exclusively served and identified with African-Americans.

Daniel Hale Williams was of African-American and Scots-Irish ancestry. Although members of his family passed as white, he exclusively served and identified with African-Americans.

Laws dating from 17th-century colonial America defined children of African slave mothers as taking the status of their mothers and born into slavery regardless of the race or status of the father, under partus sequitur ventrem. The association of slavery with a "race" led to slavery as a racial caste. But, most families of free people of color formed in Virginia before the American Revolution were the descendants of unions between white women and African men, who frequently worked and lived together in the looser conditions of the early colonial period.[151] While interracial marriage was later prohibited, white men frequently took sexual advantage of slave women, and numerous generations of multiracial children were born. By the late 1800s it had become common among African Americans to use passing to gain educational opportunities as did the first African-American graduate of Vassar College, Anita Florence Hemmings.[152] Some 19th-century categorization schemes defined people by proportion of African ancestry: a person whose parents were black and white was classified as mulatto, with one black grandparent and three white as quadroon, and with one black great-grandparent and the remainder white as octoroon. The latter categories remained within an overall black or colored category, but before the Civil War, in Virginia and some other states, a person of one-eighth or less black ancestry was legally white.[153] Some members of these categories passed temporarily or permanently as white.

After whites regained power in the South following Reconstruction, they established racial segregation to reassert white supremacy, followed by laws defining people with any apparent or known African ancestry as black, under the principle of hypodescent.[153]

However, since several thousand blacks have been crossing the color line each year, millions of white Americans have relatively recent African ancestors (of the last 250 years). A statistical analysis done in 1958 estimated that 21 percent of the white population had some African ancestors. The study concluded that the majority of Americans of African descent were today classified as white and not black.[154]

Hispanic and Latino American identity

A typical Latino American family may have members with a wide range of racial phenotypes, meaning a Latino couple may have children who look white and black and/or Native American and/or Asian.[155] Latino Americans have several self-identifications; most Latinos identify as "Some other race", while others identify as white and/or black and/or Native American and/or Asian.

Latinos of darker skin tones are noted as having limited media appearance; critics and Latinos of color have accused Latin American media of overlooking dark-skinned individuals in favor of those that are of lighter complexion, blonde-haired and blue/green-eyed – especially in regards to actors and actresses on telenovelas – rather than the typical nonwhite Latin Americans.[156][157][158][159][160][161][162][163][164]

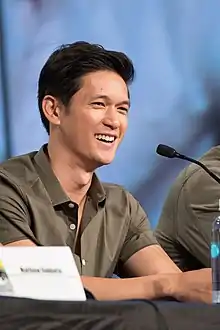

Harry Shum Jr. was born in Limón, Costa Rica, the son of Chinese immigrants. His mother is a native of Hong Kong and his father is from Guangzhou, China.

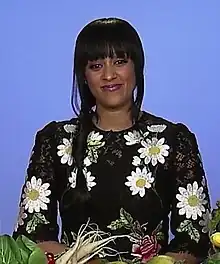

Harry Shum Jr. was born in Limón, Costa Rica, the son of Chinese immigrants. His mother is a native of Hong Kong and his father is from Guangzhou, China. Stacey Dash is the daughter of a Mexican-American mother Linda Dash (née Lopez;[165][166] d. 2017)[167] and Dennis Dash, an African-American.[166]

Stacey Dash is the daughter of a Mexican-American mother Linda Dash (née Lopez;[165][166] d. 2017)[167] and Dennis Dash, an African-American.[166]

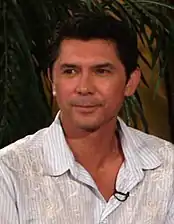

Adrian Grenier mother is Mexican (Spanish, Indigenous) and some French.[171] His father is of English, Scottish, Irish and German ancestry.[171]

Adrian Grenier mother is Mexican (Spanish, Indigenous) and some French.[171] His father is of English, Scottish, Irish and German ancestry.[171]

John H. Sununu was born to a Salvadoran mother of Lebanese descent and an American father of Palestinian and Lebanese descent.

John H. Sununu was born to a Salvadoran mother of Lebanese descent and an American father of Palestinian and Lebanese descent. According to DNA testing, Eva Longoria's Mexican-American ancestry consists of 70% European, 27% Asian and Indigenous and 3% African origin.[174]

According to DNA testing, Eva Longoria's Mexican-American ancestry consists of 70% European, 27% Asian and Indigenous and 3% African origin.[174]

Pacific Islander American identity

During the 19th century, Christian missionaries from Europe and the United States followed Western traders to the Hawaiian Islands, leading to a wave of Western migration to the Kingdom of Hawaii. Westerners in the Hawaiian Islands often intermarried with Native Hawaiian women, including Hawaiian royalty. These developments eventually led to a gradual change in the beauty standards of Native Hawaiian women to a more westernized standard, which was reinforced by the refusal of Westerners to marry dark-skinned Hawaiians.[175]

While some American Pacific Islanders continue traditional cultural endogamy, many within this population now have mixed racial ancestry, sometimes combining European, Native American, as well as East Asian ancestry. The Hawaiians originally described the mixed race descendants as hapa. The term has evolved to encompass all people of mixed Asian and/or Pacific Islander ancestry. Subsequently, many ethnic Chinese also settled on the islands and married into the Pacific Islander populations.

There are many other Pacific Islanders outside of Hawaii that do not share this common history with Hawaii and Asian populations are not the only race that Pacific Islanders mix with.

.jpg.webp) Princess Kaʻiulani was of Indigenous Hawaiian and Scots-American descent.[176]

Princess Kaʻiulani was of Indigenous Hawaiian and Scots-American descent.[176]

Jason Momoa was born to a mother of Native American, Irish and German ancestry and a father of Indigenous Hawaiian ancestry.[182]

Jason Momoa was born to a mother of Native American, Irish and German ancestry and a father of Indigenous Hawaiian ancestry.[182]

Eurasian-American identity

In its original meaning, an Amerasian is a person born in Asia to an Asian mother and a U.S. military father. Colloquially, the term has sometimes been considered synonymous with Asian-American, to describe any person of mixed American and Asian parentage, regardless of the circumstances. The term "wasian" is also common slang to describe the individuals.

According to the United States Census Bureau, concerning multiracial families in 1990, the number of children in interracial families grew from less than one-half million in 1970 to about two million in 1990.[186]

According to James P. Allen and Eugene Turner from California State University, Northridge, by some calculations the largest part white biracial population is white/American Indian and Alaskan Native, at 7,015,017; followed by white/black at 737,492; then white/Asian at 727,197; and finally white/Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander at 125,628.[20]

The U.S. Census categorizes Eurasian responses in the "some other race" section as part of the Asian race.[18] The Eurasian responses which the U.S. Census officially recognizes are Indo-European, Amerasian, and Eurasian.[18]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Norah Jones was born in Brooklyn, New York to an English-American mother and Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar of Bengali descent.

Norah Jones was born in Brooklyn, New York to an English-American mother and Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar of Bengali descent. Sean Lennon is the son of Japanese multimedia artist Yoko Ono, and English and Irish descended John Lennon.[191]

Sean Lennon is the son of Japanese multimedia artist Yoko Ono, and English and Irish descended John Lennon.[191]

.jpg.webp)

Afro-Asian-American identity

Chinese men entered the United States as laborers, primarily on the West Coast and in western territories. Following the Reconstruction era, as blacks set up independent farms, white planters imported Chinese laborers to satisfy their need for labor. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed and Chinese workers who chose to stay in the U.S. were unable to have their wives join them. In the South, some Chinese married into the black and mulatto communities, as generally, discrimination meant they did not take white spouses. They rapidly left working as laborers and set up groceries in small towns throughout the South. They worked to get their children educated and socially mobile.[198]

The Afro-Asian population drastically increased by the 1950s, with a number of Afro-Asians born to African American fathers and Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or Filipino mothers due to African Americans who enrolled in the military and developed relationships with Asian women abroad. Other groups of Afro-Asians are those who are of Caribbean American descent and are considered Dougla, or of Indian or Indo-Caribbean and African or Afro-Caribbean descent.

As of the census of 2000, there were 106,782 Afro-Asian individuals in the United States.[199]

Sonja Sohn is part African-American and Korean.[204]

Sonja Sohn is part African-American and Korean.[204]

Tommy Pham is an American baseball player whose mother is black and his father was born in Vietnam to a Vietnamese mother and an African-American father.

Tommy Pham is an American baseball player whose mother is black and his father was born in Vietnam to a Vietnamese mother and an African-American father.

In fiction

The figure of the "tragic octoroon" was a stock character of abolitionist literature: a mixed-race woman raised as if a white woman in her white father's household, until his bankruptcy or death has her reduced to a menial position[206] She may even be unaware of her status before being reduced to victimization.[207] The first character of this type was the heroine of Lydia Maria Child's "The Quadroons" (1842), a short story.[207] This character allowed abolitionists to draw attention to the sexual exploitation in slavery and, unlike portrayals of the suffering of the field hands, did not allow slaveholders to retort that the sufferings of Northern mill hands were no easier. The Northern mill owner would not sell his own children into slavery.[208]

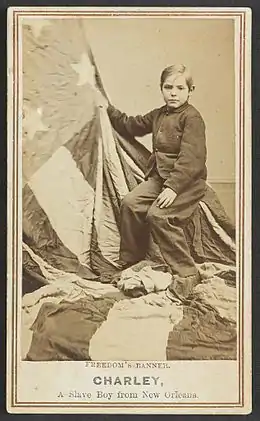

Abolitionists sometimes featured attractive, escaped mulatto slaves in their public lectures to arouse sentiments against slavery. They showed Northerners those slaves who looked like them rather than an "Other"; this technique, which is labeled White slave propaganda, collapsed the separation between peoples and made it impossible for the public to ignore the brutality of slavery.[209]

Charles W. Chesnutt, an author of the post-Civil War era, explored stereotypes in his portrayal of multiracial characters in southern society in the postwar years. Even characters who had been free and possibly educated before the war had trouble making a place for themselves in the postwar years. His stories feature mixed-race characters with complex lives. William Faulkner also portrayed the lives of mixed-race people and complex interracial families in the postwar South.

Comic book writer and filmmaker Greg Pak wrote that while white filmmakers have used multiracial characters explore themes about race and racism, many of these characters created stereotypes that Pak described were: "Wild Half-Castes", "sexually destructive antagonists explicitly or implicitly perceived as unable to control the instinctive urges of their non-white heritage" who exhibited the same racial stereotypes of their "full blood" counterparts, symbolically used by filmmakers to "[perpetuate] the association of multiraciality with sexual aberration and violence"; the "Tragic Mulatto", "a typically female character who tries to pass for white but finds disaster when her non-white heritage is revealed" whose plight used by filmmakers to "to critique racism by inspiring pity"; and the "Half Breed Hero", an "empowering" stereotype whose objective of "[inspiring] identification as he actively resists white racism" is contradicted by the character being played by a white actor, reinforcing a "white liberal's dream of inclusion and authenticity than an honest depiction of a multiracial character's experiences." Pak noted that "Wild Half Caste" and "Tragic Mulatto" characters possess little to no character development and that while many multiracial characters have appeared more frequently in films without reinforcing stereotypes, white filmmakers have mostly avoided addressing their ethnicities.[210]

See also

References

- "ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. December 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country". United States census. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- Jones, Nicholas A.; Smith, Amy Symens. "The Two or More Races Population: 2000. Census 2000 Brief" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- "B02001. RACE – Universe: TOTAL POPULATION". 2006 American Community Survey. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2008. has 6.1 million (2.0%)

- Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (2010). Faces of America: How 12 Extraordinary Americans Reclaimed Their Pasts. New York University Press.

- Root, Multiracial Experience, pp. xv–xviii

- "Obama raises profile of mixed-race Americans", San Francisco Chronicle July 21, 2008.

- "Home Page". www.freeafricanamericans.com.

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1995–2012

- "Campaigners From History: Olaudah Equiano". Anti-Slavery International. 2007. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Kolchin, Peter (1993). Slavery in America, 1619–1877. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-2568-X.

- PBS (May 1999). "Jefferson's Blood: Mixed Race America". WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- Yuen Thompson, Beverly (2006). The Politics of Bisexual/Biracial Identity: A Study of Bisexual and Mixed Race Women of Asian/Pacific Islander Descent (PDF) (Reprint ed.). Snakegirl Press. pp. 25–26. OCLC 654851035. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- Nitardy, Charlotte (May 14, 2008). "Identity Problems in Biracial Youth". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Stephen M. Quintana, Clark McKown (ed.) (2008). Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child. John Wiley & Sons. p. 211. ISBN 978-0470189801. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Lang, Susan S. (November 2, 2005). "Interracial relationships are on the increase in U.S., but decline with age, Cornell study finds". Chronicle Online. Cornell University. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Rodriguez, Cindy (December 8, 2000). "Civil rights groups wary of Census data on race". The Boston Globe. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- "Census 1990: Ancestry Codes". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on May 2, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- Tate, Eric (July 8, 1997). "Multiracial Group Views Change to Census as a Victory". The Multiracial Activist. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Cohn, D'Vera (April 6, 2011). "Multi-Race and the 2010 Census". Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- "Multiracial Children". aacap.org. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "The Rise of Intermarriage". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- {{quote="Wardle (1989) says that today, parents assume one of three positions as to the identity of their interracial children. Some insist that their child is 'human above all else' and that race or ethnicity is irrelevant, while others choose to raise their children with the identity of the parent of color. Another growing group of parents is insisting that the child have the ethnic, racial, cultural and genetic heritage of both parents."}}

- "Thandie Newton – Actress". Mixed-Race Celebrities. Intermix. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Leland, John; Beals, Gregory (February 1, 2008). "In Living Colors". Newsweek. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

Being multiracial can still be problematic. Most constructions of race in America revolve around a peculiar institution known as the 'one-drop rule' ... The one-drop conceit shapes both racism—creating an arbitrary 'caste'—and the collective response against it. To identify as multiracial is to challenge this logic, and consequently, to fall outside both camps.

-

"Many monoracials do view a multiracial identity as a choice that denies loyalty to the oppressed racial group. We can see this issue enacted currently over the debate of the U.S. census to include a multiracial category— some oppressed monoracial groups believe this category would decrease their numbers and 'benefits."

- Thiphavong, Chris. "Recognizing the Legitimacy of Multiracial Individuals Through Hapa Issues Forum and the UCLA Hapa Club". UCLA Hapa Club. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

Many students who called themselves 'half black/Asian/etc.' came to college in search of cultural knowledge but found themselves unwelcome in groups of peers that were 'whole' ethnicities.' (Renn, 1998) She found that as a result of this exclusion, many multiracial students expressed the need to create and maintain a self-identified multiracial community on campus. Multiracial people may identify more with each other, because "they share the experience of navigating campus life as multiracial people," (Renn, 1998) than with their component ethnic groups. Multiracial students of different ancestries have their own experiences in common.

- Root, Maria P. P. (2001). Love's Revolution: Interracial Marriage. Temple University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-56639-826-8. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

Women with children, especially biracial children, have fewer chances for remarriage than childless women. And because the children of divorce tend to remain with mothers, becoming incorporated into new families when their mothers remarry, interracial children are more threatening markers of race and racial authenticity for families in which race matters.

- Johnson, Kevin R. (August 2000). "Multiracialism: The Final Piece of the Puzzle". How Did You Get to Be Mexican, A White/Brown Man's Search for Identity. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Wallace, Don. ""Moana" Star Auli'i Cravalho is Not Your Average Disney Princess". Honolulu Magazine. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- @auliicravalho (January 21, 2017). "Yes indeed! I've got the luck of the Irish" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Wang, Frances Kai-Hwa (October 7, 2015). "The Next Disney Princess is Native Hawaiian AuliCravalho". NBC News. New York: NBCUniversal. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- "Keanu Reeves Film Reference biography". Film Reference. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- Hoover, Will (August 18, 2002). "Rooted in Kuli'ou'ou Valley". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- "NEHGS – Articles". Newenglandancestors.org. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Myself When I am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus, Gene Santoro (Oxford University Press, 1994) ISBN 0-19-509733-5

- Mingus, Charles: Beneath the Underdog: His Life as Composed by Mingus. New York, NY: Vintage, 1991.

- Sarah Warn (December 2003). "Jennifer Beals Tackles Issues of Race, Sexuality on The L Word". AfterEllen. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- "The New Face of Politics…An Interview with Kamala Harris". DesiClub. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- "PM Golding congratulates Kamala Harris-daughter of Jamaican – on appointment as California's First Woman Attorney General". Jamaican Information Service. December 2, 2010. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- Hattenstone, Simon (June 12, 2010). "Who, me? Why everyone is talking about Rebecca Hall". The Guardian. London. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- Isenberg, Barbara (November 8, 1992). "MUSIC No-Risk Opera? Not Even Close Maria Ewing, one of the most celebrated sopranos in opera, leaps again into the role of Tosca, keeping alive her streak of acclaimed performances while remaining true to herself". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- McLellan, Joseph (November 15, 1990). "Article: Extra-Sensuous Perception;Soprano Maria Ewing, a Steamy 'Salome'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- Marsh, Robert C. (December 18, 1988). "Growth of Maria Ewing continues with 'Salome' // Role of princess proves crowning achievement". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- Stated on Finding Your Roots, January 4, 2022

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "Why Do So Many People Claim They Have Cherokee In Their Blood? - Nerve". www.nerve.com. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Smithers, Gregory D. (October 1, 2015). "Why Do So Many Americans Think They Have Cherokee Blood?". Slate. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "The Cherokee Syndrome - Daily Yonder". www.dailyyonder.com. February 10, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Hitt, Jack (August 21, 2005). "The Newest Indians". The New York Times. Retrieved October 22, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- Bryc, Katarzyna; Durand, Eric Y.; Macpherson, J. Michael; Reich, David; Mountain, Joanna L. (January 2015). "The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 4289685. PMID 25529636.

- Carl Zimmer (December 24, 2014). "White? Black? A Murky Distinction Grows Still Murkier". The New York Times. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

The researchers found that European-Americans had genomes that were on average 98.6 percent European, .19 percent African, and .18 Native American.

- Nieves, Evelyn (March 3, 2007). "Putting to a Vote the Question 'Who Is Cherokee?'". The New York Times. Retrieved October 22, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- Adams, Paul (July 10, 2011). "Blood affects US Indian identity". BBC News. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "What Percentage Indian Do You Have to Be in Order to Be a Member of a Tribe or Nation? - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "Disappearing Indians, Part II: The Hypocrisy of Race In Deciding Who's Enrolled - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "How much Cherokee is he?: Editor's Note. Cherokee Phoenix". June 1, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- Bell, Steve; et al. "IndiVisible: African-Native American Lives in the Americans – Shared Spirits". Billy Bowlegs III (1862–1965) This Seminole Indian elder and historian, said to be a descendant of African American intermarriage with the Seminole, adopted the name of the legendary resistance fighter Billy Bowlegs II (1810–64). The "patchwork" pattern covering his turban expresses the influence of African ovpispisi (bits and pieces)—sewing typical of the Suriname Maroons and Ashanti who married into the tribe. Smithsonian Institution: National Museum of the American Indian. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- Biography ramillacody.net. Accessed July 15, 2010.

- "Kansapedia: Charles Curtis". Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved January 13, 2012.