Mochica language

Mochica (also Yunga, Yunca, Chimú, Muchic, Mochika, Muchik, Chimu) is an extinct language formerly spoken along the northwest coast of Peru and in an inland village. First documented in 1607, the language was widely spoken in the area during the 17th century and the early 18th century. By the late 19th century, the language was dying out and spoken only by a few people in the village of Etén, in Chiclayo. It died out as a spoken language around 1920, but certain words and phrases continued to be used until the 1960s.[1]

| Mochica | |

|---|---|

| Chimu | |

| Yunga | |

| Native to | Peru |

| Region | Lambayeque |

| Extinct | c. 1920 |

Chimuan?

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | omc |

omc | |

| Glottolog | moch1259 |

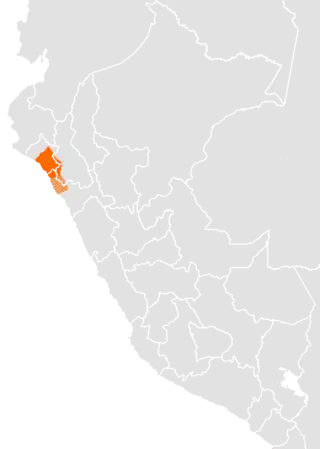

Approximate extent of Mochica before replacement by Spanish. | |

It is best known as the supposed language of the Moche culture, as well as the Chimú culture/Chimor.

Classification

Mochica is usually considered to be a language isolate,[2] but has also been hypothesized as belonging to a wider Chimuan language family. Stark (1972) proposes a connection with Uru–Chipaya as part of a Maya–Yunga–Chipayan macrofamily hypothesis.[3]

Language contact

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Trumai, Arawak, Kandoshi, Muniche, Barbakoa, Cholon-Hibito, Kechua, Mapudungun, Kanichana, and Kunza language families due to contact. Jolkesky (2016) also suggests that similarities with Amazonian languages may be due to the early migration of Mochica speakers down the Marañón and Solimões.[4]

Varieties

"Southern Chimú" varieties listed by Loukotka (1968) are given below.[5]

- Chimú - around Trujillo, Peru

- Eten - Loukotka (1968) reported a few speakers in the villages of Eten and Monsefú, department of Lambayeque

- Mochica - once spoken on the coast of the department of Libertad

- Casma - once spoken on the Casma River, department of Ancash (unattested)

- Paramonga - once spoken on the Fortaleza River, department of Ancash (unattested)

Typology

Mochica is typologically different from the other main languages on the west coast of South America, namely the Quechuan languages, Aymara, and the Mapuche language. Further, it contains rare features such as:

- a case system in which cases are built on each other in a linear sequence; for example, the ablative case suffix is added to the locative case, which in turn is added to an oblique case form;

- all nouns have two stems, possessed and non-possessed;

- an agentive case suffix used mainly for the agent in passive clauses; and

- a verbal system in which all finite forms are formed with the copula.

Phonology

The reconstruction or recovery of the Mochican sounds is problematic. Different scholars who worked with the language used different notations. Both Carrera Daza like Middendorf, devoted much space to justify the phonetic value of the signs they used, but neither was completely successful in clearing the doubts of interpretation of these symbols. In fact their interpretations differ markedly, casting doubt on some sounds.

Lehman made a useful comparison of existing sources, enriched with observations of 1929. The long-awaited field notes of Brüning from 1904 to 1905 have been kept in the Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg, though still unpublished. An additional complication in spellings interpretation of different scholars is the fact that between the 16th and the 19th century the language experienced a remarkable phonological change that make even more risky to use the latest data to understand older material.[6]

Vowels

The language probably had six simple vowels and six more elongated vowels: /i, iː, ä, äː, e, eː, ø, øː, o, oː, u, uː/. Carrera Daza and Middendorf gave mismatched systems that can be put in approximate correspondence:

| Carrera Daza | a, â | e | i | o, ô | u, û | œ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middendorf | a, ā, ă | e (ē) | ī, (i), ĭ | ō, (o), ŏ | u, ū, ŭ | ä, ů |

Morphology

Some suffixes in Mochica as reconstituted by Hovdhaugen (2004):[7]

- sequential suffix: -top

- purpose suffix: -næm

- gerund suffixes: -læc and -ssæc

- gerund suffix: -(æ)zcæf

- gerund suffix: -(æ)d

Lexicon

Some examples of lexical items in Mochica from Hovdhaugen (2004):[7]

Nouns

Possessed and non-possessed nouns in Mochica:

| gloss | possessed noun | non-possessed noun |

|---|---|---|

| 'lord' | çiec | çiequic |

| 'father' | ef | efquic |

| 'son' | eiz | eizquic |

| 'nostrils' | fon | fænquic |

| 'eyes' | locɥ | lucɥquic |

| 'soul' | moix | moixquic |

| 'hand' | mæcɥ | mæcɥquic |

| 'farm' | uiz | uizquic |

| 'bread, food' | xllon | xllonquic |

| 'head' | falpæng | falpic |

| 'leg' | tonæng | tonic |

| 'human flesh' | ærqueng | ærquic |

| 'ear' (but med in medec 'in the ears') | medeng | medquic |

| 'belly, heart' (pol and polæng appear to be equivalents) | polæng / pol | polquic |

| 'lawyer' | capæcnencæpcæss | capæcnencæpæc |

| 'heaven' | cuçias | cuçia |

| 'dog' | fanuss | fanu |

| 'duck' | felluss | fellu |

| 'servant' | ianass | yana |

| 'sin' | ixllæss | ixll |

| 'ribbon' | llaftuss | llaftu |

| 'horse' | colæd | col |

| 'fish' | xllacæd | xllac |

| '(silver) money' | xllaxllæd | xllaxll |

| 'maiz' | mangæ | mang |

| 'ceiling' | cɥapæn | cɥap |

| 'creator' | chicopæcæss | chicopæc |

| 'sleeping blanket' | cunur | cunuc |

| 'chair' (< fel 'to sit') | filur | filuc |

| 'cup' (< man 'to drink, to eat') | manir | manic |

| 'toy' (< ñe(i)ñ 'to play') | ñeñur | ñeñuc |

Locative forms of Mochica nouns:

| noun stem | locative form |

|---|---|

| fon 'nostrils' | funæc 'in the nostrils' |

| loc 'foot' | lucæc 'on the feet' |

| ssol 'forehead' | ssulæc 'in the forehead' |

| locɥ 'eye' | lucɥæc 'in the eyes' |

| mæcɥ 'hand' | mæcɥæc 'in the hand' |

| far 'holiday' | farræc 'on holidays' |

| olecɥ 'outside' | olecɥæc 'outside' |

| ssap 'mouth' | ssapæc 'in the mouth' |

| lecɥ 'head' | lecɥæc 'on the head' |

| an 'house' | enec 'in the house' |

| med 'ear' | medec 'in the ears' |

| neiz 'night' | ñeizac 'in the nights' |

| xllang 'sun' | xllangic 'in the sun' |

Quantifiers

Quantifiers in Mochica:

| quantifier | meaning and semantic categories |

|---|---|

| felæp | pair (counting birds, jugs, etc.) |

| luc | pair (counting plates, drinking vessels, cucumbers, fruits) |

| cɥoquixll | ten (counting fruits, ears of corn, etc.) |

| cæss | ten (counting days) |

| pong | ten (counting fruits, cobs, etc.) |

| ssop | ten (counting people, cattle, reed, etc., i.e. everything that is not money, fruits, and days) |

| chiæng | hundred (counting fruits, etc.) |

Numerals

Mochica numerals:

| Numeral | Mochica |

|---|---|

| 1 | onæc, na- |

| 2 | aput, pac- |

| 3 | çopæl, çoc- |

| 4 | nopæt, noc- |

| 5 | exllmætzh |

| 6 | tzhaxlltzha |

| 7 | ñite |

| 8 | langæss |

| 9 | tap |

| 10 | çiæcɥ, -pong, ssop, -fælæp, cɥoquixll |

| 20 | pacpong, pacssop, etc. |

| 30 | çocpong, çocssop, etc. |

| 40 | nocpong, nocssop, etc. |

| 50 | exllmætzhpong, exllmætzhssop, etc. |

| 60 | tzhaxlltzhapong, tzhaxlltzhassop, etc. |

| 70 | ñitepong, ñitessop, etc. |

| 80 | langæsspong, langæssop, etc. |

| 90 | tappong, tapssong, etc. |

| 100 | palæc |

| 1000 | cunô |

Surviving records

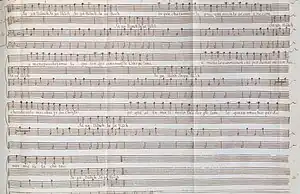

The only surviving song in the language is a single tonada, Tonada del Chimo, preserved in the Codex Martínez Compañón among many watercolours illustrating the life of Chimú people during the 18th century:

1st voice: Ja ya llũnch, ja ya llõch

Ja ya llũnch, ja ya lloch [sic]

In poc cha tanmuisle pecan muisle pecan e necam

2nd voice: Ja ya llũnch, ja ya llõch

Ja ya llũnch

1st voice: E menspocehifama le qui

ten que consmuiſle Cuerpo lens

e menslocunmunom chi perdonar moitin Roc

2nd voice: Ja ya llõch

Ja ya llũnh,[sic] ja ya llõch

1st voice: Chondocolo mec checje su chriſto

po que si ta mali muis le cuer po[sic] lem.

lo quees aoscho perdonar

me ñe fe che tas

2nd voice: Ja ya llũnch, ja ya llõch

Ja ya llũnch, ja ya llõch— [8]

Quingnam, possibly the same as Lengua (Yunga) Pescadora, is sometimes taken to be a dialect, but a list of numerals was discovered in 2010 and is suspected to be Quingnam or Pescadora, not Mochica.

Learning program

The Gestión de Cultura of Morrope in Peru has launched a program to learn this language, in order to preserve the ancient cultural heritage in the area. This program has been well received by people and adopted by many schools, and also have launched other activities such as the development of ceramics, mates, etc.

Further reading

- Brüning, Hans Heinrich (2004). Mochica Wörterbuch / Diccionario mochica: Mochica-castellano, castellano-mochica. Lima: Universidad San Martín de Porres.

- Hovdhaugen, Even (2004). Mochica. Munich: LINCOM Europa.

- Schumacher de Peña, G. (1992). El vocabulario mochica de Walter Lehmann (1929) comparado con otras fuentes léxicas. Lima: UNSM, Instituto de Investigación de Lingüística Aplicada.

References

- Adelaar, Willem F. H. (1999). "Unprotected languages, the silent death of the languages in Northern Peru". In Herzfeld, Anita; Lastra, Yolanda (eds.). The social causes of the disappearance and maintenance of languages in the nations of America: papers presented at the 49° International Congress of Americanists, Quito, Ecuador, July 7–11, 1997. Hermosillo: USON. ISBN 978-968-7713-70-0.

- Campbell, Lyle (2012). "Classification of the indigenous languages of South America". In Grondona, Verónica; Campbell, Lyle (eds.). The Indigenous Languages of South America. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 59–166. ISBN 978-3-11-025513-3.

- Stark, Louisa R. (1972). "Maya-Yunga-Chipayan: A New Linguistic Alignment". International Journal of American Linguistics. 38 (2): 119–135. doi:10.1086/465193. ISSN 0020-7071. S2CID 145380780.

- Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho de Valhery (2016). Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas (Ph.D. dissertation) (2 ed.). Brasília: University of Brasília.

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- Cerrón Palomino, Rodolfo (1995). The language of Naimlap. Reconstruction and obsolescence of the mochica. Lima: Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. ISBN 978-84-8390-986-7.

- Hovdhaugen, Even (2004). Mochica. Munich: LINCOM Europa.

- "Bajo y Tamboril para baylar cantando. [Índice:] Tonada del Chimo.". Trujillo del Perú . Volumen 2 (in Spanish). Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. p. 180. Retrieved 13 September 2023.