Barbacoan languages

Barbacoan (also Barbakóan, Barbacoano, Barbacoana) is a language family spoken in Colombia and Ecuador.

| Barbacoan | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Colombia and Ecuador |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Barbacoan |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | barb1265 |

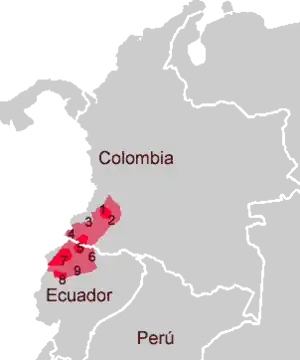

Barbacoan language at present, and probable areas in the 16th century:

| |

Genealogical relations

The Barbacoan languages may be related to the Páez language. Barbacoan is often connected with the Paezan languages (including Páez); however, Curnow (1998) shows how much of this proposal is based on misinterpretation of an old document of Douay (1888). (See: Paezan languages.)

Other more speculative larger groupings involving Barbacoan include the Macro-Paesan "cluster", the Macro-Chibchan stock, and the Chibchan-Paezan stock.

Language contact

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Atakame, Cholon-Hibito, Kechua, Mochika, Paez, Tukano, Umbra, and Chibchan (especially between Guaymí and Southern Barbacoan branches) language families due to contact.[1]

Languages

Barbacoan consists of 6 languages:

- Northern

- Awan (also known as Awa or Pasto)

- Awa Pit (also known as Cuaiquer, Coaiquer, Kwaiker, Awá, Awa, Telembi, Sindagua, Awa-Cuaiquer, Koaiker, Telembí)

- Pasto–Muellama

- Coconucan (also known as Guambiano–Totoró)

- Southern ? (Cayapa–Tsafiki)

Pasto, Muellama, Coconuco, and Caranqui are now extinct.

Pasto and Muellama are usually classified as Barbacoan, but the current evidence is weak and deserves further attention. Muellama may have been one of the last surviving dialects of Pasto (both extinct, replaced by Spanish) — Muellama is known only by a short wordlist recorded in the 19th century. The Muellama vocabulary is similar to modern Awa Pit. The Cañari–Puruhá languages are even more poorly attested, and while often placed in a Chimuan family, Adelaar (2004:397) thinks they may have been Barbacoan.

The Coconucan languages were first connected to Barbacoan by Daniel Brinton in 1891. However, a subsequent publication by Henri Beuchat and Paul Rivet placed Coconucan together with a Paezan family (which included Páez and Paniquita) due a misleading "Moguex" vocabulary list. The "Moguex" vocabulary turned out to be a mix of both Páez and Guambiano languages (Curnow 1998). This vocabulary has led to misclassifications by Greenberg (1956, 1987), Loukotka (1968), Kaufman (1990, 1994), and Campbell (1997), among others. Although Páez may be related to the Barbacoan family, a conservative view considers Páez a language isolate pending further investigation. Guambiano is more similar to other Barbacoan languages than to Páez, and thus Key (1979), Curnow et al. (1998), Gordon (2005), and Campbell (2012)[2] place Coconucan under Barbacoan. The moribund Totoró is sometimes considered a dialect of Guambiano instead of a separate language, and, indeed, Adelaar & Muysken (2004) state that Guambiano-Totoró-Coconuco is best treated as a single language.

The Barbácoa (Barbacoas) language itself is unattested, and is only assumed to be part of the Barbacoan family. Nonetheless, it has been assigned an ISO code, though the better-attested and classifiable Pasto language has not.

Loukotka (1968)

Below is a full list of Barbacoan language varieties listed by Loukotka (1968), including names of unattested varieties.[3]

- Barbacoa group

- Barbácoa of Colima - extinct language once spoken on the Iscuandé River and Patia River, Nariño department, Colombia. (Unattested.)

- Pius - extinct language once spoken around the Laguna Piusbi, in the Nariño region. (Unattested.)

- Iscuandé - extinct language once spoken on the Iscuandé River in the Nariño region. (Unattested.)

- Tumaco - extinct language once spoken around the modern city of Tumaco, department of Nariño. (Unattested.)

- Guapi - extinct language once spoken on the Guapi River, department of Cauca. (Unattested.)

- Cuaiquer / Koaiker - spoken on the Cuaiquer River in Colombia.

- Telembi - extinct language once spoken in the Cauca region on the Telembi River. (Andre 1884, pp. 791–799.)

- Panga - extinct language once spoken near the modern city of Sotomayor, Nariño department. (Unattested.)

- Nulpe - extinct language once spoken in the Nariño region on the Nulpe River. (Unattested.)

- Cayápa / Nigua - language spoken now by a few families on the Cayapas River, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador.

- Malaba - extinct language once spoken in Esmeraldas province on the Mataje River. (Unattested.)

- Yumbo - extinct language once spoken in the Cordillera de Intag and the Cordillera de Nanegal, Pichincha province, Ecuador. The population now speaks only Quechua. (Unattested.)

- Colorado / Tsachela / Chono / Campaz / Satxíla / Colime - language still spoken on the Daule River, Vinces River, and Esmeraldas River, provinces of Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas and Los Ríos, Ecuador.

- Colima - extinct language once spoken on the middle course of the Daule River, Guayas province. (Unattested.)

- Cara / Caranqui / Imbaya - extinct language once spoken in the province of Imbabura and on the Guayllabamba River, Ecuador. The population now speaks Spanish or Quechua.

- Sindagua / Malla - extinct language once spoken on the Tapaje River, Iscuandé River, Mamaonde River, and Patia River, department of Nariño, Colombia. (H. Lehmann 1949; Ortiz 1938, pp. 543–545, each only a few patronyms and toponyms.)

- Muellama - extinct language of the Nariño region, once spoken in the village of Muellama.

- Pasta - extinct language once spoken in Carchi province, Ecuador, and in the department of Nariño in Colombia around the modern city of Pasto, Colombia.

- Mastele - extinct language once spoken on the left bank of the Guaitara River near the mouth, department of Nariño. (Unattested.)

- Quijo - once spoken on the Napo River and Coca River, Oriente province, Ecuador. The tribe now speaks only Quechua. (Ordónez de Ceballos 1614, f. 141-142, only three words.)

- Mayasquer - extinct language once spoken in the villages of Mayasquer and Pindical, Carchi province, Ecuador. The present population speaks only Quechua. (Unattested.)

- Coconuco group

- Coconuco - language spoken by a few families at the sources of the Cauca River, department of Cauca, Colombia.

- Guamíca / Guanuco - extinct language once spoken in the village of Plata Vieja in Colombia.

- Guambiana / Silviano - spoken in the villages of Ambató, Cucha and partly in Silvia.

- Totaró - spoken in the villages of Totoró and Polindara.

- Tunía - once spoken on the Tunía River and Ovejas River. (Unattested.)

- Chesquio - extinct language once spoken on the Sucio River. (Unattested.)

- Patia - once spoken between the Timbío River and Guachicono River. (Unattested.)

- Quilla - original and extinct language of the villages of Almaguer, Santiago, and Milagros. The present population speaks only a dialect of Quechua. (Unattested.)

- Timbío - once spoken on the Timbío River. (Unattested.)

- Puracé - once spoken around the Laguna de las Papas and Puracé Volcano. (Unattested.)

- Puben / Pubenano / Popayan - extinct language of the plains of Popayán, department of Cauca. (Unattested.)

- Moguex - spoken in the village of Quisgó and in a part of the village of Silvia.

Vocabulary

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items.[3]

gloss Cuaiquer Telembi Cayápa Colorado Cara Muellama one marabashpá tumuni main manga two pas pas pályo paluga pala three kotiá kokia péma paiman ear kail puːngi punki tongue maulcha nigka ohula hand chitoé chʔto fiapapa tädaʔé foot mitá mito rapapa medaʔé mit water pil pil pi pi bi pi stone uʔúk shúpuga chu su pegrané maize piaʔá pishu piox pisa fish shkarbrodrúk changúko guatsá guasa kuas house yaʔál yal ya yá ya

Proto-language

| Proto-Barbacoan | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Barbacoan languages |

Proto-Barbacoan reconstructions and reflexes (Curnow & Liddicoat 1998):[4]

no. gloss Proto-Barbacoan Guambiano Totoró Awapit Cha’palaachi Tsafiqui 1 be *i- i- i- 2 blow *ut- utʂ- otʂ- us- 3 come *ha- a- ha- ha- 4 cook *aj- aj- (a-) aj- 5 corn *pijo pija pijo 6 do *ki- ki- ki- ki- 7 dry *pur pur pul 8 eye *kap kap kap-[tʂul] (kasu) ka-[puka] ka-[’ka] 9 feces *pi pɨ pe pe 10 firewood *tɨ tʂɨ sɨ te te 11 flower *uʃ u o uʃ 12 fog *waniʃ waɲi wapi waniʃ 13 get up *kus- ku̥s- kuh- (ku’pa-) 14 go *hi- i- hi- hi- 15 go up *lo- nu- lu- lo- 16 hair *aʃ aʃ a 17 house *ja ja ja (jal) ja ja 18 I *la na na na la 19 land *to su tu to 20 lie down *tso tsu tsu tu tsu tso 21 listen *miina- mina- meena- 22 louse *mũũ (mũi) muuŋ mu mu 23 mouth *ɸit pit fiʔ-[paki] ɸi-[’ki] 24 no/negative *ti ʃi ti 25 nose *kim-ɸu kim kim kimpu̥ kinɸu 26 path *mii mii mi-[ɲu] mi-[nu] 27 river, water *pii pi pi pii pi pi 28 rock *ʃuk ʂuk ʂuk uk ʃu-[puka] su 29 smoke *iʃ iʃ iʃ 30 sow *wah- waa- wah- wa’-[ke-] 31 split *paa- paa- paa- 32 tear ("eye-water") *kap pi kappi kappi kapi ka’pĩ 33 that *sun sun hun hun 34 thorn *po pu pu pu po 35 tree, stick *tsik tsik tʃi tsi-[de] 36 two *paa pa pa (paas) paa (palu) 37 what? *ti tʃi (tʃini) ʃi ti-[n] ti 38 who? *mo mu mu-[n] mo 39 wipe clean *kis- ki̥s- kih- 40 yellow *lah- na-[tam] lah-[katata] (la’ke) 41 you (sg.) *nu (ɲi) (ɲi) nu ɲu nu 42 armadillo *ʃul ? ʂulə ʂolɨ ulam 43 dirt *pil ? pirə pirɨ pil 44 moon *pɨ ? pəl pɨl pe 45 suck *tsu- ? tuk- tsu- 46 tail *mɨ ? məʃ, mətʂ mɨʂ mɨta me 47 three *pɨ ? pən pɨn pema pemã 48 tooth *tu ? tʂukul tʂokol sula

See also

References

- Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho de Valhery (2016). Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas (Ph.D. dissertation) (2 ed.). Brasília: University of Brasília.

- Campbell, Lyle (2012). "Classification of the indigenous languages of South America". In Grondona, Verónica; Campbell, Lyle (eds.). The Indigenous Languages of South America. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 59–166. ISBN 9783110255133.

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- Curnow, Timothy J.; Liddicoat, Anthony J. (1998). The Barbacoan languages of Colombia and Ecuador. Anthropological Linguistics, 40 (3).

Bibliography

- Adelaar, Willem F. H.; & Muysken, Pieter C. (2004). The languages of the Andes. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge University Press.

- Brend, Ruth M. (Ed.). (1985). From phonology to discourse: Studies in six Colombian languages (p. vi, 133). Language Data, Amerindian Series (No. 9). Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Beuchat, Henri; & Rivet, Paul. (1910). Affinités des langues du sud de la Colombie et du nord de l'Équateur. Le Mouséon, 11, 33-68, 141-198.

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. (1981). Comparative Chibchan phonology. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania).

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. (1991). Las lenguas del área intermedia: Introducción a su estudio areal. San José: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo. (1993). La familia chibcha. In (M. L. Rodríguez de Montes (Ed.), Estado actual de la clasificación de las lenguas indígenas de Colombia (pp. 75–125). Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

- Curnow, Timothy J. (1998). Why Paez is not a Barbacoan language: The nonexistence of "Moguex" and the use of early sources. International Journal of American Linguistics, 64 (4), 338-351.

- Curnow, Timothy J.; & Liddicoat, Anthony J. (1998). The Barbacoan languages of Colombia and Ecuador. Anthropological Linguistics, 40 (3).

- Douay, Léon. (1888). Contribution à l'américanisme du Cauca (Colombie). Compte-Rendu du Congrès International des Américanistes, 7, 763-786.

- Gerdel, Florence L. (1979). Paez. In Aspectos de la cultura material de grupos étnicos de Colombia 2, (pp. 181–202). Bogota: Ministerio de Gobierno and Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Key, Mary R. (1979). The grouping of South American languages. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

- Landaburu, Jon. (1993). Conclusiones del seminario sobre clasificación de lenguas indígenas de Colombia. In (M. L. Rodríguez de Montes (Ed.), Estado actual de la clasificación de las lenguas indígenas de Colombia (pp. 313–330). Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

- Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Studies Center, University of California.

- Slocum, Marianna C. (1986). Gramática páez (p. vii, 171). Lomalinda: Editorial Townsend.

- Stark, Louisa R. (1985). Indigenous languages of lowland Ecuador: History and current status. In H. E. Manelis Khan & L. R. Stark (Eds.), South American Indian languages: Retrospect and prospect (pp. 157–193). Austin: University of Texas Press.

External links

- Proel: Familia Barbacoana

- Proel: Sub-tronco Paezano