Iranian cuisine

Iranian cuisine (Persian: آشپزی ایرانی, romanized: Āshpazī Irānī) are the culinary traditions of Iran. Due to the historically common usage of the term "Persia" to refer to Iran in the Western world,[2][3][4] it is alternatively known as Persian cuisine, despite Persians being only one of a multitude of Iranian ethnic groups who have contributed to Iran's culinary traditions.[lower-alpha 1]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

The cuisine of Iran has made extensive contact throughout its history with the cuisines of its neighbouring regions, including Caucasian cuisine, Central Asian cuisine, Greek cuisine, Levantine cuisine, Mesopotamian cuisine, Russian cuisine and Turkish cuisine.[6][7][8][9] Aspects of Iranian cuisine have also been significantly adopted by Indian cuisine and Pakistani cuisine through various historical Persianate sultanates that flourished during Muslim rule on the Indian subcontinent, with the most notable and impactful of these polities being the Mughal Empire.[10][11][12]

Typical Iranian main dishes are combinations of rice with meat, vegetables and nuts. Herbs are frequently used, along with fruits such as plums, pomegranates, quince, prunes, apricots and raisins. Characteristic Iranian spices and flavourings such as saffron, cardamom, and dried lime and other sources of sour flavoring, cinnamon, turmeric and parsley are mixed and used in various dishes.

Outside of Iran, a strong presence of Iranian cuisine can be found in cities with significant Iranian diaspora populations, namely the San Francisco Bay Area, Toronto,[13][14][15][16] Houston and especially Los Angeles and its environs.[13][14][17]

History

Among the writings available from the Middle Persian scripts, the treatise of Khosrow and Ridag, points about stews and foods and the way of using them and how they are obtained in the Sassanid period are found as valid references in compiling the history of cooking in Iran. The names of many of the Iranian dishes and culinary terms that have been translated can be seen in Arabic language books. Naturally the customs and habits of the Arabs influenced the Iranians, specifically in Abbasid period.

Ancient Persian philosophers and physicians have influenced the preparation of Iranian foods to follow the rules of the strengthening and weakening characteristics of foods based on the Iranian traditional medicine.[18]

Historical Iranian cookbooks

Although the Arabic cookbooks written under the rule of the Abbasid Caliphate—one of the Arab caliphates which ruled Iran after the Muslim invasion—include some recipes with Iranian names, the earliest surviving classical cookbooks in Persian are two volumes from the Safavid period. The older one is entitled "Manual on cooking and its craft" (Kār-nāmeh dar bāb e tabbāxī va sanat e ān) written in 927/1521 for an aristocratic patron at the end of the reign of Ismail I. The book originally contained 26 chapters, listed by the author in his introduction, but chapters 23 through 26 are missing from the surviving manuscript. The recipes include measurements for ingredients—often detailed directions for the preparation of dishes, including the types of utensils and pots to be used—and instructions for decorating and serving them. In general, the ingredients and their combinations in various recipes do not differ significantly from those in use today. The large quantities specified, as well as the generous use of such luxury ingredients as saffron, suggest that these dishes were prepared for large aristocratic households, even though in his introduction, the author claimed to have written it "for the benefit of the nobility, as well as the public."

The second surviving Safavid cookbook, entitled "The substance of life, a treatise on the art of cooking" (Māddat al-ḥayāt, resāla dar ʿelm e ṭabbāxī), was written about 76 years later by a chef for Abbas I. The introduction of that book includes elaborate praise of God, the prophets, the imams, and the shah, as well as a definition of a master chef. It is followed by six chapters on the preparation of various dishes: four on rice dishes, one on qalya, and one on āsh. The measurements and directions are not as detailed as in the earlier book. The information provided is about dishes prepared at the royal court, including references to a few that had been created or improved by the shahs themselves. Other contemporary cooks and their specialties are also mentioned.[19]

Staple foods

Rice

The usage of rice, at first a specialty of the Safavid Empire's court cuisine, evolved by the end of the 16th century CE into a major branch of Iranian cookery.[20] Traditionally, rice was most prevalent as a major staple item in northern Iran and the homes of the wealthy, while bread was the dominant staple in the rest of the country.

Varieties of rice in Iran include gerde, domsia (literally meaning black-tail, because it is black at one end), champa, doodi (smoked rice), Lenjan (from Lenjan County), Tarom (from Tarom County), and anbarbu.

The following table includes three primary methods of cooking rice in Iran.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Polow and chelow | Chelow is plain rice served as an accompaniment to a stew or kebab, while polow is rice mixed with something. They are, however, cooked in the same way. Rice is prepared by soaking in salted water and then boiling it. The parboiled rice (called chelow) is drained and returned to the pot to be steamed. This method results in an exceptionally fluffy rice with the rice grains separated and not sticky. A golden crust called tadig is created at the bottom of the pot using a thin layer of bread or potato slices. Often, tadig is served plain with only a rice crust. Meat, vegetables, nuts, and fruit are sometimes added in layers or mixed with the chelow and then steamed. When chelow is in the pot, the heat is reduced and a thick cloth or towel is placed under the pot lid to absorb excess steam. |

| Kateh | Rice that is cooked until the water is absorbed completely. It is the traditional dish of Gilan Province. |

| Dami | Rice that is cooked almost the same as kateh, but at the start, ingredients that can be cooked thoroughly with the rice (such as grains and beans) are added. While making kateh, the heat is reduced to a minimum until the rice and other ingredients are almost cooked. If kept long enough on the stove without burning and over-cooking, dami and kateh can also produce tadig. A special form of dami is tachin, which is a mixture of yogurt, chicken (or lamb), and rice, plus saffron and egg yolks. |

Bread

Second only to rice is the production and use of wheat. The following table lists several forms of flatbread and pastry bread commonly used in Iranian cuisine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fruits and vegetables

The agriculture of Iran produces many fruits and vegetables. Thus, a bowl of fresh fruit is common on Iranian tables, and vegetables are standard side dishes with most meals. These are not only enjoyed fresh and ripe as desserts but are also combined with meat as accompaniments to main dishes.[23] When fresh fruits are not available, a large variety of dried fruits such as dates, figs, apricots, plums and peaches are served instead. Southern Iran is one of the world's major date producers, where some special cultivars such as the Bam date are grown.

Vegetables such as pumpkins, spinach, green beans, fava beans, courgette, varieties of squash, onion, garlic and carrot are commonly used in Iranian dishes. Tomatoes, cucumbers and scallion often accompany a meal. While the eggplant is "the potato of Iran",[24] Iranians are fond of fresh green salads dressed with olive oil, lemon juice, salt, chili, and garlic.

Fruit dolma is probably a specialty of Iranian cuisine. The fruit is first cooked, then stuffed with meat, seasonings, and sometimes tomato sauce. The dolma is then simmered in meat broth or a sweet-and-sour sauce.[25]

Verjuice, a highly acidic juice made by pressing unripe grapes or other sour fruit, is used in various Iranian dishes.[26] It is mainly used within soup and stew dishes, but also to simmer a type of squash dolma. Unripe grapes are also used whole in some dishes such as khoresh e qure (lamb stew with sour grapes). As a spice, verjuice powder (pudr e qure) is sometimes reinforced by verjuice and then dried.

Typical spices

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Advieh or chāshni refers to a wide variety of pungent vegetables and dried fruits that are used in Iranian cuisine to flavor food.

One of the traditional and most widespread Iranian spices is saffron, derived from the flower of Crocus sativus. Rose water, a flavored water made by steeping rose petals in water, is also a traditional and common ingredient in many Iranian dishes.

Persian hogweed (golpar), which grows wild in the humid mountainous regions of Iran, is used as a spice in various Iranian soups and stews. It is also mixed with vinegar into which broad beans are dipped before eating.

Some other common spices are cardamom, made from the seeds of several Elettaria and Amomum plants; shevid, an annual herb in the celery family Apiaceae; mahleb, an aromatic spice made from the seeds of Prunus mahaleb; and limu amani, dried lime.

There are also several traditional combinations of spices, two of which are arde, made from toasted ground hulled sesame seeds, and delal sauce, made of heavily salted fresh herbs such as cilantro and parsley.

Typical food and drinks

Typical Iranian cuisine includes a wide variety of dishes, including several forms of kebab, stew, soup, and pilaf dishes, as well as various salads, desserts, pastries, and drinks.

Kebab

In Iran, kebabs are served either with rice or with bread. A dish of chelow white rice with kebab is called chelow kabab. The rice can also be prepared using the kateh method, and hence the dish would be called kateh kabab.

The following table lists several forms of kebab used in Iranian cuisine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stew

Khoresh is an Iranian form of stew, which is usually accompanied by a plate of white rice. A khoresh typically consists of herbs, fruits, and meat pieces, flavored with tomato paste, saffron, and pomegranate juice. Other non-khoresh types of stew such as dizi are accompanied by bread instead of rice.

Several Iranian stew dishes are listed within the following table.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

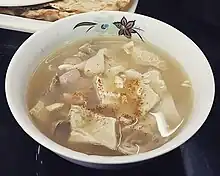

Soup and āsh

There are various forms of soup in Iranian cuisine, including sup e jow (barley soup), sup e esfenaj (spinach soup), sup e qarch (mushroom soup), and several forms of thick soup. A thick soup is referred to as āsh in Iran, which is an Iranian traditional form of soup.[37] Also, shole qalamkar is the Iranian term for "hodge-podge" soup,[38] a soup made of a mixture of various ingredients.

The following table lists a number of soup and āsh dishes in Iranian cuisine.

|

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

|

|

_cuisine.jpg.webp) |

|

Polow and dami

Apart from dishes of rice with kebab or stew, there are various rice-based Iranian dishes cooked in the traditional methods of polow and dami.

Polow is the Persian word for pilaf and it is also used in other Iranian languages, in the English language it may have variations in spelling. A polow dish includes rice stuffed with cuts of vegetables, fruits, and beans, usually accompanied by either chicken or red meat. Dami dishes are similar to polow in that they involve various ingredients with rice, however they are cooked using the dami method of cooking the dish all in one pot.

The following are a number of traditional Iranian rice-based dishes:

|

|

Albalu polow: Rice with sour cherries and slices of chicken or red meat. | .JPG.webp) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

|

_with_sliced_tomato_and_kosher_dills.jpg.webp) |

|

Sirabij: A type of garlic omelette. |

|

_Pizza.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

Appetizers

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Desserts

In 400 BC, the ancient Iranians invented a special chilled food, made of rose water and vermicelli, which was served to royalty in summertime.[49] The ice was mixed with saffron, fruits, and various other flavors. Today, one of the most famous Iranian desserts in the semi-frozen noodle dessert known as faloodeh, which has its roots in the city of Shiraz, a former capital of the country.[50][51] Bastani e zaferani, Persian for "saffron ice cream", is a traditional Iranian ice cream which is also commonly referred to as "the traditional ice cream". Other typical Iranian desserts include several forms of rice, wheat and dairy desserts.

The following is a list of several Iranian desserts.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Snacks

Cookies appear to have their origins in 7th-century Iran, shortly after the use of sugar became relatively common in the region.[53] There are numerous traditional native and adopted types of snack food in modern Iran, of which some are listed within the following table.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

Drinks

.jpg.webp)

Iran is one of the world's major tea producers,[57] mostly cultivated in its northern regions. In Iranian culture, tea (čāy) is widely consumed[58][59] and is typically the first thing offered to a guest.[60] Iranians traditionally put a lump of sugar cube in the mouth before drinking the tea.[61] Rock candies are also widely used, typically flavored with saffron.

Iran's traditional coffee (qahve, or kāfe) is served strong, sweet, and "booby-trapped with a sediment of grounds".[62] In 16th-century Safavid Iran, coffee was initially used for medical purposes among the society.[63] Traditional coffeehouses were popular gatherings, in which people drank coffee, smoked tobacco, and recited poetry—especially the epic poems of Shahnameh.[64] In present-day Iran, cafés are trendy mostly in urban areas, where a variety of brews and desserts are served.[62] Turkish coffee is also popular in Iran, more specifically among Iranian Azeris.[65][66]

Wine (mey) has also a significant presence in Iranian culture. Shirazi wine is Iran's historically most famous wine production, originating from the city of Shiraz.[67][68][69] By the 9th century, the city of Shiraz had already established a reputation for producing the finest wine in the world,[68] and was Iran's wine capital. Since the 1979 Revolution, alcoholic beverages have been prohibited in Iran; though non-Muslim recognized minorities (i.e. Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians) are allowed to produce alcoholic beverages for their own use.[70] While non-alcoholic beer (ābjow) is available from legal outlets, other citizens prepare their alcoholic beverages illegally through the minority groups[71][72][73] and largely from Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey.[74]

Araq sagi, literally meaning "doggy distillate", is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage in Iran which contains at least 65% pure ethanol. It is usually produced at homes from raisins, and is similar to Turkish rakı.[75] Prior to the 1979 Revolution, it had been produced traditionally in several cities of Iran. Since it was outlawed following the 1979 Revolution, it has become a black market and underground business.

The following table lists several Iranian cold beverages.

|

.jpg.webp) |

|

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

|

Regional Iranian cuisine

Azerbaijani cuisine

The Azerbaijani people, living primarily in the region of Azerbaijan in northwestern Iran, have a number of local dishes that include Bonab kabab (Binab kababı),[79] the dumpling dish of joshpara (düşbərə), an offal-based dish named jaqul baqul typically containing liver and heart,[80] a variety of āsh called kələcoş,[81] a variation of qeyme that is called pıçaq, and a variation of kufte that is called Tabriz meatballs. There is also the traditional pastry of shekerbura (şəkərbura), which is identical to Khorasan's shekarpare (šekarpāre). Despite the influences from Turkey, the food tastes noticeably Iranian, though also with its own unique features, such as using more lemon juice and butter than other groups of Iranians.[82]

Balochi cuisine

Meat and dates are the main ingredients in the cuisine of Iran's southeastern region of Baluchistan.[83][84] Rice is primarily cultivated in the region of Makran.[83][84] Foods that are specific to the Iranian region of Baluchistan include tanurche (tarōnča; tanurče), a local variety of grilled meat that is prepared in a tanur, doogh-pa (dōq-pâ), a type of khoresh that contains doogh, and tabahag (tabâhag), that is meat prepared with pomegranate powder.[83][84] Baluchi cuisine also includes several date-based dishes, as well as various types of bread.[83][84]

Caspian cuisine

The southern coast of the Caspian Sea, which consists of the Iranian provinces of Gilan, Mazanderan, Alborz, and Golestan, has a fertile environment that is also reflected in its cuisine.[85][86] Kateh is a method of cooking rice that originates from this region.[87] This type of rice dish is also eaten there as a breakfast meal, either heated with milk and jam or cold with cheese and garlic. Caviar fish roes also hail from this region, and are typically served with eggs in frittatas and omelettesor eaten simply with Lavash and Butter. Fish is commonly eaten in the Gilan province, where Caspian Kutum is a staple[88] and usually served fried[89] along with rice. Smoked fish (Persian: ماهی دودی, Romanized: Mahi doodi) is also popular in Gilan[90] and usually incorporated into rice by steaming the two together.[91] Local cookies (koluče) of the region are popular desert items,[86] particularly those from the region of Fuman. Another notable dessert from this region is Reshteh Khoshkar (Persian: رشتهخشکار), consisting of fried rice flour dough filled with sugar and nuts. Medlar is also commonly eaten in Gilan[92] and locally referred to as "Konos" (Persian: کونوس).

Kurdish cuisine

The region of Kurdistan in western Iran is home to a variety of local āsh, pilaf, and stew dishes.[93] Some local Kurdish dishes include a traditional grilled rib meat that is called dande kabāb,[94] a type of khoresh made of chives that is called xoreš-e tare,[95] and a dish of rice and potatoes that is called sib polow.[96]

Southern Iranian cuisine

The food of southern Iran is typically spicy.[97] Mahyawa is a tangy sauce made of fermented fish in this region. Being a coastal region, Khuzestan's cuisine includes especially seafood, as well as some unique local beverages.[98] In southern Khuzestan, there is also a variation of kufte that is known as kibbeh and is made of ground meat, cracked wheat, different types of herbs and vegetables and various spices.

Turkmen cuisine

Iran's Turkmen people are predominantly centered in the Iranian provinces of Golestan and North Khorasan. Chegderme (čekderme) is a Turkmen dish made of rice, meat, and tomato paste.[99]

Structure

Breakfast

The basic traditional Iranian breakfast consists of a variety of flat breads, butter cubes, white cheese, whipped heavy cream (sarshir; often sweetened with honey), nuts (especially walnuts) and a variety of fruit jams and spreads.

Many cities and towns across Iran feature their own distinct versions of breakfast dishes. Pache, a popular traditional dish widely eaten in Iran and the neighboring Caucasus, is almost always only served from three in the morning until sometime after dawn, and specialty restaurants (serving only pache) are only open during those hours.

Lunch and dinner

Traditional Iranian cooking is done in stages, at times needing hours of preparation and attention. The outcome is a well-balanced mixture of herbs, meat, beans, dairy products, and vegetables. Major staples of Iranian food that are usually eaten with every meal include rice, various herbs, cheese, a variety of flat breads, and some type of meat (usually poultry, beef, lamb, or fish). Stew over rice is by far the most popular dish, and the constitution of these vary by region.

Traditional table setting and etiquette

Traditional Iranian table setting firstly involves the tablecloth, called sofre, and is spread out over either a table or a rug. Main dishes are concentrated in the middle, surrounded by smaller dishes containing appetizers, condiments, and side dishes, all of which are nearest to the diners. When the food is perfectly served, an invitation is made to seat at the sofre and start having the meal.

See also

- List of Iranian foods

- Mazanderani cuisine

- Kurdish cuisine

- Azerbaijani cuisine

- Agriculture in Iran

- Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, a medieval Indian Persian language cookbook

Notes

- This issue is still debated today.[5]

References

- Walker, H. (1992). Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1991: Public Eating: Proceedings. Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. Prospect Books. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-907325-47-5. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- "Cultural Life". Tehrān. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

Persian cuisine is characterized by the use of lime and saffron, the blend of meats with fruits and nuts, a unique way of cooking rice, and Iranian hospitality. Food is subtly spiced, delicate in flavour and appearance, and not typically hot or spicy. Many recipes date back to ancient times; Iran's historical contacts have assisted in the exchange of ingredients, flavours, textures, and styles with various cultures ranging from the Mediterranean Sea region to China, some of whom retain these influences today.

- Clark, Melissa (19 April 2016). "Persian Cuisine, Fragrant and Rich With Symbolism". New York Times.

- Yarshater, Ehsan Persia or Iran, Persian or Farsi Archived 2010-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, Iranian Studies, vol. XXII no. 1 (1989)

- Majd, Hooman, The Ayatollah Begs to Differ: The Paradox of Modern Iran, by Hooman Majd, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, September 23, 2008, ISBN 0-385-52842-6, 9780385528429. p. 161

- "Persian Cuisine, a Brief History". Culture of IRAN. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- electricpulp.com. "ĀŠPAZĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- "Iranian Food". Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Culture of IRAN". Cultureofiran.com. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Achaya, K. T. (1994). Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- Stanton; et al. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-4522-6662-6.

- Mina Holland (6 March 2014). The Edible Atlas: Around the World in Thirty-Nine Cuisines. Canongate Books. pp. 207–. ISBN 978-0-85786-856-5.

- Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (3 February 2016). "Top five Persian restaurants in London". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Ta, Lien (27 November 2011). "The Best Persian Food In LA (PHOTOS)". HuffPost.

- "Bay Area chef circles back to childhood with Iranian breads". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- Nuttall-Smith, Chris (13 December 2013). "The 10 best new restaurants in Toronto in 2013". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Whitcomb, Dan (4 January 2018). "Los Angeles' large Iranian community cheers anti-regime protests". Reuters.

- Seeney, Belinda (16 February 2011). "Balancing the hot and cold". Redcliffe, Queensland. The Redcliffe & Bayside Herald.

- Ghanoonparvar, Mohammad R. "Cookbooks". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Fragner, B. (1987). ĀŠPAZĪ. Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Davidson, Alan; Jaine, Tom (2014). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7.

- Tales of a Kitchen (5 March 2013). "Persian date bread with turmeric and cumin (Komaj)".

- Ramazani, Nesta. "Uses of the Fruit in Cooking". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- "Production/Crops for Eggplant in 2013". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2015. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Ghanoonparvar, M. R. "Dolma". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Ramazani, N. "ĀB-ḠŪRA". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- "Saffron and lemon chicken (Joojeh Kabab)". Irish Times. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- Burke, Andrew; Elliott, Mark (15 September 2010). "MAIN COURSES: Kabab". Iran. Ediz. Inglese. Lonely Planet. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-74220-349-2.

- Sally Butcher (10 October 2013). "Kebab-e-Chenjeh". Snackistan. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-909815-15-5.

- Aashpazi.com. "KABAB TABEI".

- Vatandoust, Soraya. (13 March 2015). "Khoresh-e Karafs". Authentic Iran: Modern Presentation of Ancient Recipes. Xlibris Corporation. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4990-4061-6.

- Ramazani, Nesta. (1997). "Khoresht-e aloo". Persian Cooking: A Table of Exotic Delights. Iranbooks. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-936347-77-6.

- Dana-Haeri, Jila; Lowe, Jason; Ghorashian, Shahrzad (28 February 2011). "Glossary". New Persian Cooking: A Fresh Approach to the Classic Cuisine of Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-85771-955-3.

- Goldstein, Joyce (12 April 2016). "Persian Stew with Lamb or Beef, Spinach, and Prunes". The New Mediterranean Jewish Table: Old World Recipes for the Modern Home. Illustrated by Hugh D'Andrade. (1st, ebook ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-520-96061-9. LCCN 2020757338. OL 27204905M. Wikidata Q114657881.

- Ramazani, Nesta. (1997). Persian Cooking: A Table of Exotic Delights. Iranbooks. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-936347-77-6.

- Dana-Haeri, Jila; Ghorashian, Shahrzad; Lowe, Jason (28 February 2011). "Khoresht-e gharch". New Persian Cooking: A Fresh Approach to the Classic Cuisine of Iran. I.B.Tauris. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-85771-955-3.

- Elāhī, ʿE. "ĀŠ (thick soup), the general term for a traditional Iranian dish comparable to the French potage.". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Trost, Alex; Kravetsky, Vadim (13 June 2014). 100 of the Most Delicious Iranian Dishes. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4944-9809-2.

- Ramazani, Nesta. (1997). "Chicken Soup (Soup-e Morgh)". Persian Cooking: A Table of Exotic Delights. Iranbooks. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-936347-77-6.

- Vatandoust, Soraya. (13 March 2015). "Soup-e Jow". Authentic Iran: Modern Presentation of Ancient Recipes. Xlibris Corporation. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4990-4061-6.

- Meftahi, Ida. (14 July 2017). Gender and Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-317-62062-4.

sirabi-va-shirdun

- Shafia, Louisa. (16 April 2013). "Morasa polo". The New Persian Kitchen. Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed. ISBN 978-1-60774-357-6.

- "Jeweled Rice (Morasa Polo)". Parisa's Kitchen. 9 October 2014.

- Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdī, ʻAlī Akbar (2006). Culture and Customs of Iran. Bloomsbury. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-313-32053-8.

- Batmanglij, Najmieh. (2007). "Adas polow". A Taste of Persia: An Introduction to Persian Cooking. I. B. Tauris, Limited. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-84511-437-4.

- Batmanglij, Najmieh. (2007). "Baqala polow". A Taste of Persia: An Introduction to Persian Cooking. I. B. Tauris, Limited. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-84511-437-4.

- Batmanglij, Najmieh. (1990). Food of Life: A Book of Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies. Mage Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-934211-27-7.

- Vatandoust, Soraya. (13 March 2015). "Zeytoon Parvardeh". Authentic Iran: Modern Presentation of Ancient Recipes. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4990-4061-6.

- "History of Ice Cream". thenibble.com.

- "Shiraz Sights" Archived 2016-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, at BestIranTravel.com

- Marks, Gil (17 November 2010). Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-94354-0.

- Vatandoust, Soraya. (13 March 2015). "Chapter 8". Authentic Iran: Modern Presentation of Ancient Recipes. p. 186. ISBN 978-1-4990-4061-6.

- "History of Cookies - Cookie History". Whatscookingamerica.net. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Ramazani, Nesta. (1997). "Rice Flour Cookies (Nan-e Berenji)". Persian Cooking: A Table of Exotic Delights. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-936347-77-6.

- Marks, Gil. (17 November 2010). "Shirini". Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. ISBN 978-0-544-18631-6.

- Butcher, Sally. (18 November 2012). "Peckham Delight". Veggiestan: A Vegetable Lover's Tour of the Middle East. ISBN 978-1-909108-22-6.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—Production FAOSTAT. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Williams, Stuart. (October 2008). "DRINKING". Iran - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. ISBN 978-1-85733-598-9.

Iranians are obsessive tea drinkers

- Maslin, Jamie. (13 October 2009). Iranian Rappers and Persian Porn: A Hitchhiker's Adventures in the New Iran. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-60239-791-0.

Iran is a nation of obsessive tea drinkers

- Burke, Andrew; Elliott, Mark; Mohammadi, Kamin & Yale, Pat (2004). Iran. Lonely Planet. pp. 75–76. ISBN 1-74059-425-8.

Iranian guest tea.

- Edelstein, Sari. (2011). Food, Cuisine, and Cultural Competency for Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professionals. p. 595. ISBN 978-0-7637-5965-0.

Tea is usually sweetened with lumps of sugar. Most Iranians sip their tea through these lumps of sugar by placing the lump inside their cheek

- Burke, Andrew; Elliott, Mark (15 September 2010). "Coffee". Iran. Ediz. Inglese. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-74220-349-2.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. (2005). The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900. p. 146. ISBN 0-691-11855-8.

- Newman, Andrew J. (31 March 2006). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-86064-667-6.

- "Getting Your Buzz with Turkish coffee". ricksteves.com. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Brad Cohen. "BBC - Travel - The complicated culture of Bosnian coffee". bbc.com. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Marjolein Muys (1 April 2010). Substance Use Among Migrants: The Case of Iranians in Belgium. Asp / Vubpress / Upa. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-90-5487-564-2.

- Entry on "Persia" in J. Robinson (ed), "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, p. 512-513, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- Hugh Johnson, "The Story of Wine", New Illustrated Edition, p. 58 & p. 131, Mitchell Beazley 2004, ISBN 1-84000-972-1

- Edelstein, Sari. (2011). Food, Cuisine, and Cultural Competency for Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professionals. p. 595. ISBN 978-0-7637-5965-0.

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, alcoholic beverages have been strictly banned...non-Muslim minority groups...are entitled to produce wine for their own consumption.

- Afshin Molavi (12 July 2010). The Soul of Iran: A Nation's Struggle for Freedom. W. W. Norton. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-393-07875-6.

- A. Christian Van Gorder (2010). Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-7391-3609-6.

- Kevin Boyle; Juliet Sheen (7 March 2013). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. Routledge. pp. 423–. ISBN 978-1-134-72229-7.

- Saeed Kamali Dehghan (25 June 2012). "Iranian pair face death penalty after third alcohol offence | World news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Abdulah Skaljic (1985). Turcizmi u srpskohrvatskom-hrvatskosrpskom jeziku. Sarajevo.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Edelstein, Sari. (2011). Food, Cuisine, and Cultural Competency for Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professionals. p. 595. ISBN 978-0-7637-5965-0.

aab-e havij, a carrot juice

- Duguid, Naomi. (6 September 2016). Taste of Persia: A Cook's Travels Through Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and Kurdistan. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-57965-727-7.

...havij bastani, a kind of ice cream float, made with Persian ice cream and carrot juice

- J. & A. Churchill. (1878). The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions, Volume 37. p. 385.

Khakshir is imported from Persia...

- "کباب بناب از کجا آمده است؟" [Where has Bonab kebab come from?]. Khabaronline News Agency (in Persian). 5 March 2011.

- "طرز تهیه جغول بغول" [Method of preparing Jaqul Baqul]. Tabnak News (in Persian). 14 February 2018.

- "آشنایی با غذاهای خوشمزه چهار گوشه ایران" [Getting to know delicious foods from the four corners of Iran]. Hamshahri (in Persian). 27 March 2013.

- Collinson, Paul; Macbeth, Helen (2014). Food in Zones of Conflict: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Berghahn Books. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-78238-403-8.

- "بفرمایید غذاهای بلوچی" [Check out Baluchi foods]. Jam-e-Jam Online (in Persian). 18 May 2013.

- "غذاهای سنتی سیستان و بلوچستان ریشه در باور و طبیعت دارد" [The traditional foods of Sistan and Baluchistan are rooted in belief and nature]. Mehr News (in Persian). 14 March 2016.

- Burke, Andrew; Maxwell, Virginia (2012). Lonely Planet Iran. ISBN 978-1-74321-320-9.

- "A foodie tour of Iran: it's poetry on a plate". The Guardian. 29 October 2016.

- Batmanglij, Najmieh (2007). A Taste of Persia: An Introduction to Persian Cooking. I.B.Tauris. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-84511-437-4.

- "Iran ranks 14th among fishery producing countries". www.payvand.com. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- "Sabzi Polo ba Mahi recipe - Fried fish with saffron and herb rice". I got it from my Maman. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- "طرز تهیه ماهی دودی خوشمزه مخصوص گیلان". خبرگزاری ایلنا (in Persian). Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- "Bibalani G.H., Mosazadeh-Sayadmahaleh F. Medicinal benefits and usage of medlar (Mespilus germanica) in Gilan Province (Roudsar District), Iran".

- "خوراک جشن دندان" [Tooth celebration food]. Hamshahri (in Persian). 20 August 2017.

- "دنده کباب' کرمانشاه ثبت ملی میشود'" ["Kermanshah's 'dande kebab' gets national registration"]. ISNA (in Persian). 15 October 2016.

- "آشنایی با روش تهیه خورش تره، غذای کردی" [Introduction to the method of preparing chives khoresh, a Kurdish food]. Hamshahri (in Persian). 15 June 2013.

- "سیب پلو" [Apple Pilaf]. IRIB - Isfahan (in Persian). Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "Taste of Persia: 10 foodie ways to see Iran". The Telegraph. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

The food of southern Iran is hot and spicy, just like its climate (...)

- "Khuzestan boasts assortment in cuisine". Iran Daily (IRNA). 4 December 2015.

- "چکدرمه'، غذای محلی ترکمنها'" ["Chekderme", local food of the Turkmen]. Jam-e-Jam Online (in Persian). 30 March 2013.

Further reading

- Daniel, Elton L.; Mahdi, Ali Akbar (2006). Culture and Customs of Iran. Greenwood Press. pp. 149–155. ISBN 978-0-313-32053-8.

- "ĀŠPAZĪ" [cooking]. Encyclopaedia Iranica. 15 December 1987.

- Matthee, Rudolph, 'Patterns of Food Consumption in Early Modern Iran', Oxford Handbook Topics in History (online edn, Oxford Academic, 5 Oct. 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935369.013.13, accessed 4 Aug. 2023.

- Neda Mollakhalili Meybodi; Maryam Tajabadi Ebrahimi; Amir Mohammad Mortazavian. Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverage of Iran. Springer.