Piedmontese language

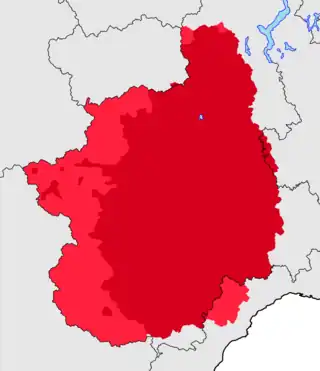

Piedmontese (English: /ˌpiːdmɒnˈtiːz/ PEED-mon-TEEZ; autonym: piemontèis [pjemʊŋˈtɛjz] or lenga piemontèisa; Italian: piemontese) is a language spoken by some 2,000,000 people mostly in Piedmont, a region of Northwest Italy. Although considered by most linguists a separate language, in Italy it is often mistakenly regarded as an Italian dialect.[2] It is linguistically included in the Gallo-Italic languages group of Northern Italy (with Lombard, Emilian, Ligurian and Romagnolo), which would make it part of the wider western group of Romance languages, which also includes French, Occitan, and Catalan. It is spoken in the core of Piedmont, in northwestern Liguria (near Savona), and in Lombardy (some municipalities in the westernmost part of Lomellina near Pavia).

| Piedmontese | |

|---|---|

| piemontèis | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Northwest Italy: Piedmont Liguria Lombardy Aosta Valley |

Native speakers | 2,000,000 (2012)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pms |

| Glottolog | piem1238 |

| ELP | Piemontese |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-of |

| |

It has some support from the Piedmont regional government but is considered a dialect rather than a separate language by the Italian central government.[2]

Due to the Italian diaspora Piedmontese has spread in the Argentinian Pampas, where many immigrants from Piedmont settled. The Piedmontese language is also spoken in some states of Brazil, along with the Venetian language.

Literature

The first documents in the Piedmontese language were written in the 12th century, the sermones subalpini, when it was extremely close to Occitan, dating from the 12th century, a document devoted to the education of the Knights Templar stationed in Piedmont.

During reinassance are attested the oldest Piedmontese literary work of secular character, are the works of Zan Zòrs Alion, poet of the duchy of Montferrat, the most famous work being the opera Jocunda.

In the 500s and 600s there are several pastoral comedies with parts in Piedmontese.

In the Baroque period, El Cont Piolèt, a comedy by Giovan Battista Tan-na d'entraive, was published.

Literary Piedmontese developed in the 17th and 18th centuries, but it did not gain literary esteem comparable to that of French or Italian, other languages used in Piedmont. Nevertheless, literature in Piedmontese has never ceased to be produced: it includes poetry, theatre pieces, novels, and scientific work.[3]

History

The first documents in the Piedmontese language were written in the 12th century, the sermones subalpini, when it was extremely close to Occitan.

Current status

In 2004, Piedmontese was recognised as Piedmont's regional language by the regional parliament,[4][5][6] although the Italian government has not yet recognised it as such. In theory, it is now supposed to be taught to children in school,[7] but this is happening only to a limited extent.

The last decade has seen the publication of learning materials for schoolchildren, as well as general-public magazines. Courses for people already outside the education system have also been developed. In spite of these advances, the current state of Piedmontese is quite grave, as over the last 150 years the number of people with a written active knowledge of the language has shrunk to about 2% of native speakers, according to a recent survey.[8] On the other hand, the same survey showed Piedmontese is still spoken by over half the population, alongside Italian. Authoritative sources confirm this result, putting the figure between 2 million (Assimil,[9] IRES Piemonte[10] and 3 million speakers (Ethnologue[11]) out of a population of 4.2 million people. Efforts to make it one of the official languages of the Turin 2006 Winter Olympics were unsuccessful.

Regional variants

Piedmontese is divided into three major groups

- Western which include the dialects of Turin and Cuneo.

- Eastern which in turn is divided into south-eastern (Astigiano, Roero, Monregalese, High Montferrat, Langarolo, Alessandrino) and north-eastern (Low Montferrat, Biellese, Vercellese, Valsesiano).

- Canavese, spoken in the Canavese region in north-western Piedmont.

The variants can be detected in the variation of the accent and variation of words. It is sometimes difficult to understand a person that speaks a different Piedmontese from the one you are used to, as the words or accents are not the same.

Eastern and western group

The Eastern Piedmontese group is more phonologically evolved than its western counterpart.

The words that in the west end with jt, jd or t in the east end with [dʒ] e/o [tʃ] for example the westerns [lajt], [tyjt], and [vɛj] (milk, all and old) in the east are [lɑtʃ], [tytʃ] and [vɛdʒ].

A typical eastern features is [i] as allophone of [e]: in word end, at the end of infinitive time of the verb, like in to read and to be (western [leze], [ese] vs. eastern [lezi], [esi]) and at words feminine plural gender. Although this development is shared partially (in the case of the infinitive time) also by most of the western dialects, including the Turin one, that is the most spoken dialect of western piedmontese (and also of the whole piedmontese language).

A morphological variation that sharply divides east and west is the indicative imperfect conjugation of irregular verbs, in the east is present the suffix ava/iva, while in the west is asìa/isìa.

And different conjugation of the present simple of the irregular verbs: dé, andé, sté (to give, to go, to stay).

| english | eastern | western | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| to give | to go | to stay | to give | to go | to stay | |

| I | dagh | vagh | stagh | don | von | ston |

| you | dè | vè | stè | das | vas | stas |

| he/she/it | da | va | sta | da | va | sta |

| we | doma | andoma | stoma | doma | andoma | stoma |

| you | déj | andéj | stéj | deve | andeve | steve |

| they | dan | van | stan | dan | van | stan |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | ||||

| voiced | d͡ʒ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | |||

| voiced | v | z | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||

/v/ is realized as labio-velar [w] between /a/ and /u/ and as [w] or [f] when in word-final position.[12][13]

Phonological process

- Apocope, i.e., dropping of all of the unstressed vowels at word end,[14]: 92–94 except /a/, which is usually centralized to [ɐ].[14]: 296–297

- Syncope i.e., weakening or dropping of unstressed pro-tonic[15]: 169–171 and post-tonic vowels: /me'luŋ/ > /mə'luŋ/ > /m'luŋ/,[16]: 37 same happens in French, and other Gallo-Romance languages. In some cases, prothesis of [ə] or [ɐ] is also present to make some consonant clusters easier to pronounce (ex. novod, "nephew" , [nʊˈvud] > [nvud] > [ɐnˈvud],[15][16] this feature is also present in Emilian.[15]

- Nasalization of vowels in front of /n/, as in Western Romance, and then shift of nasalization from the vowel to /n/ with development of the /ŋn/ cluster, and subsequent dropping of [n] (/'buna/> /'bũna/> /'buŋna/ > /'buŋa/).[16]: 51

- Development of vowels /ø/ and /y/ from [ɔ] and [uː] of Latin, respectively.[16]: 36–37

- Consonantal degemination: SERRARE > saré.

- Latin groups of occlusives [kt] and [gd] become [jd]-, as in Gallo-Romance: NOCTEM > neuit [nøi̯d]; LACTEM > làit [lɑi̯d]. Some dialects have reached the more advanced stage, with palatalization of [i̯d] to [d͡ʒ] (for example Vercelli dialect [nød͡ʒ] and [lad͡ʒ]), as happens in Spanish, Occitan, and Brazilian Portuguese.[14]: 350–351

- Palatization of [kl] and [gl] : Latin CLARUS > ciàr [tʃɑi̯r], "light", GLANDIA > gianda [ˈdʒɑŋdɐ] "nut".[14]: 552–558 [16]: 39

- The Latin unvoiced occlusive /p/, /t/, /k/, are voiced (becoming /b/, /d/, /g/), and then lenited and usually drop: FORMICAM > formìa; APRILEM > avril, CATHÉDRA > careja.[16]: 50

- Latin /k/-/g/ before front vowels, became post-alveolar affricates /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/, then /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ due to typical Western Romance assibilation, later /t͡s/ and /d͡z/ became fricatives: /s/ and /z/: CINERE > sënner; CENTUM > sent; GINGIVA > zanziva. [16]: 38

Alphabet

Piedmontese is written with a modified Latin alphabet. The letters, along with their IPA equivalent, are shown in the table below.

| Letter | IPA value | Letter | IPA value | Letter | IPA value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /a/, [ɑ] | H h | ∅ | P p | /p/ | ||

| B b | /b/ | I i | /i/ or (semivocalic) /j/ | Q q | /k/[lower-roman 1] | ||

| C c | /k/ or /tʃ/[lower-roman 2] | J j | /j/ | R r | /r/~/ɹ/ | ||

| D d | /d/ | L l | /l/ | S s | /s/, /z/[lower-roman 3] | ||

| E e | /e/ or /ɛ/[lower-roman 4] | M m | /m/ | T t | /t/ | ||

| Ë ë | /ə/ | N n | /n/ or /ŋ/[lower-roman 5] | U u | /y/, or (semivocalic) /w/, /ʊ̯/ | ||

| F f | /f/ | O o | /ʊ/, /u/ or (semivocalic), /ʊ̯/ | V v | /v/, /ʋ/, or /w/[lower-roman 6] | ||

| G g | /ɡ/ or /dʒ/[lower-roman 2] | Ò ò | /ɔ/ | Z z | /z/ | ||

- Always before u.

- Before i, e or ë, c and g represent /tʃ/ and /dʒ/, respectively.

- s is voiced [z] between vowels, at the end of words, immediately before nasal/voiced consonants.

- e is /e/ or /ɛ/ in open syllables and just /e/ in closed.

- Before consonants and at the end of words, n represents the velar nasal /ŋ/.

- v is generally /v/, /ʋ/ before dental consonants and between vowels, /w/ ([f] by some speakers) at the end of words.

Certain digraphs are used to regularly represent specific sounds as shown below.

| Digraph | IPA value | Digraph | IPA value | Digraph | IPA value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gg | /dʒ/ | gh | /ɡ/ | cc | /tʃ/ | ||

| gli | /ʎ/[lower-alpha 1] | ss | /s/ | gn | /ɲ/ | ||

| sc | /sk/, /stʃ/ | sc, scc | /stʃ/ | eu | /ø/ | ||

| sg, sgg | /zdʒ/ | ||||||

- Represents /ʎ/ in some Italian loanwords.

All other combinations of letters are pronounced as written. Grave accent marks stress (except for o which is marked by an acute to distinguish it from ò) and breaks diphthongs, so ua and uà are /wa/, but ùa is pronounced separately, /ˈya/.

Numbers

| number | piedmontese | number | piedmontese | number | piedmontese | number | piedmontese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | un | 11 | ondes | 30 | tranta | 200 | dosent |

| 2 | doi (m), doe (f) | 12 | dodes | 40 | quaranta | 300 | tersent |

| 3 | trei | 13 | terdes | 50 | sinquanta | 400 | quatsent |

| 4 | quatr | 14 | quatordes | 60 | sessanta | 500 | sinchsent |

| 5 | sinch | 15 | quindes | 70 | stanta | 600 | sessent |

| 6 | ses | 16 | sedes | 80 | otanta | 700 | setsent |

| 7 | set | 17 | disset | 90 | novanta | 800 | eutsent |

| 8 | eut | 18 | diseut | 100 | sent | 900 | neuvsent |

| 9 | neuv | 19 | disneuv | 101 | sent e un | 1000 | mila |

| 10 | des | 20 | vint | 110 | sentdes |

Characteristics

Some of the characteristics of the Piedmontese language are:

- The presence of clitic so-called verbal pronouns for subjects, which give a Piedmontese verbal complex the following form: (subject) + verbal pronoun + verb, as in (mi) i von 'I go'. Verbal pronouns are absent only in the imperative form.

- The bound form of verbal pronouns, which can be connected to dative and locative particles (a-i é 'there is', i-j diso 'I say to him').

- The interrogative form, which adds an enclitic interrogative particle at the end of the verbal form (Veus-to…? 'Do you want to...?'])

- The absence of ordinal numerals higher than 'sixth', so that 'seventh' is col che a fà set 'the one which makes seven'.

- The existence of three affirmative interjections (that is, three ways to say yes): si, sè (from Latin sic est, as in Italian); é (from Latin est, as in Portuguese); òj (from Latin hoc est, as in Occitan, or maybe hoc illud, as in Franco-Provençal, French and Old Catalan and Occitan).

- The absence of the voiceless postalveolar fricative /ʃ/ (like the sh in English sheep), for which an alveolar S sound (as in English sun) is usually substituted.

- The existence of an S-C combination pronounced [stʃ].

- The existence of a velar nasal [ŋ] (like the ng in English going), which usually precedes a vowel, as in lun-a 'moon'.

- The existence of the third Piedmontese vowel Ë, which is very short (close to the vowel in English sir).

- The absence of the phonological contrast that exists in Italian between short (single) and long (double) consonants, for example, Italian fata 'fairy' and fatta 'done (F)'.

- The existence of a prosthetic Ë sound when consonantal clusters arise that are not permitted by the phonological system. So 'seven stars' is pronounced set ëstèile (cf. stèile 'stars').

Piedmontese has a number of varieties that may vary from its basic koiné to quite a large extent. Variation includes not only departures from the literary grammar, but also a wide variety in dictionary entries, as different regions maintain words of Frankish or Lombard origin, as well as differences in native Romance terminology. Words imported from various languages are also present, while more recent imports tend to come from France and from Italian.

A variety of Piedmontese was Judeo-Piedmontese, a dialect spoken by the Piedmontese Jews until the Second World War.

Lexical comparison

Lexical comparison with other Romance languages and English:

| Gallo-Italic and Venetian | Occitano-Romance | Occitano- and Ibero-Romance | Gallo-Romance | Italo-Dalmatian | Ibero-Romance | Eastern Romance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Piedmontese | Ligurian | Emilian | Venetian | Occitan | Catalan | Aragonese | Arpitan | French | Sicilian | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | Romanian |

| chair | cadrega/ careja | carêga | scrâna | carèga | cadièra | cadira | silla | cheyére | chaise | sìeggia | sedia | silla | cadeira | scaun, catedră |

| to take | pijé/ciapé | pigiâ/ciapà | ciapèr | ciapar | prene, agafar | agafar, agarrar, replegar | agafar, replegar | prendre/acrapar | prendre | pigghiàri | prendere, pigliare | coger, tomar, pillar | pegar, tomar | a lua |

| to go/come out | surtì/seurte | sciortì | sortìr | isìr/sortir | sortir, sal(h)ir, eissir | sortir/eixir | salir, sallir, ixir, salldre | sortir/salyir | sortir | nèsciri | uscire | salir | sair | a ieși |

| to fall | droché/tombé | càzze | crodèr | cajar | caire/tombar | caure | cayer, caire | chèdre | tomber | càriri | cadere, cascare | caer, tumbar | cair, tombar | cădere |

| home | ca/meison | ca | ca | caxa/cà | casa/meison | ca/casa | casa | mêson/cà | maison | casa | casa | casa | casa | casă |

| arm | brass | brasso | brâs | bras | braç | braç | braço | brès | bras | vrazzu | braccio | brazo | braço | braț |

| number | nùmer | nùmero | nómmer | nùmaro | nòmbre | nombre | número | nombro | nombre/numéro | nùmmuru | numero | número | número | număr |

| name | nòm | nòme | nóm | nòme | nom | nom | nombre, nom | nom | nom | nomu | nome | nombre | nome | nume |

| apple | pom | méia/póma | pàm | pómo | poma | poma, maçana | maçana, poma | poma | pomme | muma/mela | mela | manzana | maçã | măr |

| to work | travajé | travagiâ | lavorè | travajar | trabalhar | treballar | treballar | travalyér | travailler | travagghiari | lavorare | trabajar | trabalhar | a lucra |

| bat (animal) | ratavolòira | ràttopenûgo | papastrel | signàpola/nòtoła | ratapenada | ratpenat, moricec | moriziego, moricec | rata volage | chauve-souris | taddarita | pipistrello | murciélago | morcego | liliac |

| school | ëscòla | schêua | scöa | scóła | escòla | escola | escuela, escola | ècuola | école | scola | scuola | escuela | escola | școală |

| wood (land) | bòsch | bòsco | bòsch | bósco | bosc | bosc | bosque | bouesc | bois | voscu | bosco | bosque | bosque | pădure |

| Mr | monsù | sciô | sior | siór | sénher | senyor | sinyor | monsior | monsieur | gnuri | signore | señor | senhor, seu | domn |

| Mrs | madama | sciâ | siora | sióra | sénhera | senyora | sinyora | madama | madame | gnura | signora | señora | senhora, dona | doamnă |

| summer | istà | istà | istê | istà | estiu | estiu | verano | étif | été | astati | estate | verano, estío | verão, estio | vară |

| today | ancheuj | ancheu | incō | incò | uèi/ancuei | avui/hui | hue | enqu'houè | aujourd'hui | ùoggi | oggi | hoy | hoje | azi |

| tomorrow | dman | domân | dmân | domàn | deman | demà | manyana, deman, maitín | deman | demain | rumani | domani | mañana | amanhã | mâine |

| yesterday | jer | vêi | iêr | jéri | gèr/ier | ahir | ahiere | hièr | hier | aìeri | ieri | ayer | ontem | ieri |

| Monday | lùn-es | lunesdì | munedé | luni | diluns | dilluns | luns | delon | lundi | lunidìa | lunedì | lunes | segunda-feira | luni |

| Tuesday | màrtes | mâtesdì | martedé | marti | dimars | dimarts | març | demârs | mardi | màrtiri | martedì | martes | terça-feira | marți |

| Wednesday | mèrcol | mâcordì | mercordé | mèrcore | dimecrès | dimecres | miercres | demécro | mercredi | mèrcuri | mercoledì | miércoles | quarta-feira | miercuri |

| Thursday | giòbia | zéuggia | giovedé | zòba | dijòus | dijous | jueus | dejo | jeudi | iòviri | giovedì | jueves | quinta-feira | joi |

| Friday | vënner | venardì | venerdé | vénare | divendres | divendres | viernes | devendro | vendredi | viènniri | venerdì | viernes | sexta-feira | vineri |

| Saturday | saba | sabbò | sâbet | sabo | dissabte | dissabte | sabado | dessandro | samedi | sabbatu | sabato | sábado | sábado | sâmbătă |

| Sunday | dominica/domigna | dumenega | dumenica | doménega | dimenge | diumenge | dominge | demenge | dimanche | rumìnica | domenica | domingo | domingo | duminică |

References

- Piedmontese on Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- La Stampa. "Per la Consulta il piemontese non è una lingua". Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- "Tàula ëd Matemàtica e Fìsica" [University-level course material - physics and calculus]. digilander.libero.it.

- "Atti del Consiglio - Mozioni e Ordini del Giorno". Consiglio regionale del Piemonte. 30 November 1999.

- "Approvazione da parte del Senato del Disegno di Legge che tutela le minoranze linguistiche sul territorio nazionale - Approfondimenti" [Text of motion 1118 in the Piedmontese Regional Parliament] (PDF). Consiglio Regionale del Piemonte. 15 December 1999.

- Piemontèis d'amblé - Avviamento Modulare alla conoscenza della Lingua piemontese; R. Capello, C. Comòli, M.M. Sánchez Martínez, R.J.M. Nové; Regione Piemonte/Gioventura Piemontèisa; Turin, 2001

- "Arbut - Ël piemontèis a scòla" [Piedmontese courses at School]. www.gioventurapiemonteisa.net.

- Knowledge and Usage of the Piedmontese Language in Turin and its Province Archived 2006-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, carried out by Euromarket, a Turin-based market research company on behalf of the Riformisti per l'Ulivo party in the Piedmontese Regional Parliament in 2003 (in Italian).

- F. Rubat Borel, M. Tosco, V. Bertolino. Il Piemontese in Tasca, a Piedmontese basic language course and conversation guide, published by Assimil Italia (the Italian branch of Assimil, the leading French producer of language courses) in 2006. ISBN 88-86968-54-X. assimil.it

- E. Allasino, C. Ferrer, E. Scamuzzi, T. Telmon (October 2007). "Le Lingue del Piemonte". www.ires.piemonte.it. Istituto di Ricerche Economiche e Sociali Piemonte.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International ISO 639-3, pms (Piemontese) Retrieved 13 June 2012

- Brero, Camillo; Bertodatti, Remo (2000). Grammatica della lingua piemontese. Torino: Ed.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Parry, Mair (1997). Piedmont. The dialects of Italy: London: Routledge. pp. 237–244.

- Hull, Geoffrey (2017). The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language. Volume 1: Historical Introduction, Phonology.

- Rohlfs, Gerhard. Grammatica storica della lingua italiana e dei suoi dialetti (in Italian).

- Cornagliotti, Anna (2015). Repertorio Etimologico Piemontese (in Italian).

Further reading

- Zallio, A. G. (1927). "The Piedmontese Dialects in the United States". American Speech. 2 (12): 501–4. doi:10.2307/452803. JSTOR 452803.

External links

- Piedmontese language at Curlie

- Cultural Association "Nòste Rèis": features online Piedmontese courses for Italian, French, English, and Spanish speakers with drills and tests

- Piemunteis.it - Online resources about piedmontese language: poems, studies, audio, free books

- Piemontese basic lexicon (several dialects) at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Omniglot's entry on Piedmontese