History of Bulgaria

The history of Bulgaria can be traced from the first settlements on the lands of modern Bulgaria to its formation as a nation-state, and includes the history of the Bulgarian people and their origin. The earliest evidence of hominid occupation discovered in what is today Bulgaria date from at least 1.4 million years ago.[1] Around 5000 BC, a sophisticated civilization already existed which produced some of the first pottery, jewellery and golden artifacts in the world. After 3000 BC, the Thracians appeared on the Balkan Peninsula. In the late 6th century BC, parts of what is nowadays Bulgaria, in particular the eastern region of the country, came under the Persian Achaemenid Empire.[2] In the 470s BC, the Thracians formed the powerful Odrysian Kingdom which lasted until 46 BC, when it was finally conquered by the Roman Empire.[3] During the centuries, some Thracian tribes fell under ancient Macedonian and Hellenistic, and also Celtic domination. This mixture of ancient peoples was assimilated by the Slavs, who permanently settled on the peninsula after 500 AD.

| History of Bulgaria |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Main category |

Meanwhile, in 632 the Bulgars formed an independent state north of the Black sea that became known as Great Bulgaria under the leadership of Kubrat. Pressure from the Khazars led to the gradual disintegration of Great Bulgaria in the second half of the 7th century. One of Kubrat's successors, Asparuh, leading some of the Bulgar tribes settled in the area around the Danube delta, and subsequently conquered Scythia Minor and Moesia Inferior from the Byzantine Empire, expanding his new kingdom further into the Balkan peninsula.[4] The crucial Battle of Ongal in 680, the peace treaty with Byzantium in 681, and the establishment of a permanent Bulgarian capital at Pliska south of the Danube mark the beginning of the First Bulgarian Empire. The new state brought together local Byzantine population and migrant population as Early Slavs under Bulgar rule, and a slow process of mutual assimilation began. In the following centuries Bulgaria established itself as a powerful empire, dominating the Balkans through its aggressive military traditions, which led to development of a distinct ethnic identity.[5] Its ethnically and culturally diverse people united under a common religion, language and alphabet which formed and preserved the Bulgarian national consciousness despite foreign invasions and influences.

In the 11th century, the First Bulgarian Empire collapsed under multiple Rus' and Byzantine attacks and wars, and was conquered and became part of the Byzantine Empire until 1185. Then, a major uprising led by two brothers, Asen and Peter of the Asen dynasty, restored the Bulgarian state to form the Second Bulgarian Empire. After reaching its apogee in the 1230s, Bulgaria started to decline due to a number of factors, most notably its geographic position which rendered it vulnerable to simultaneous attacks and invasions from many sides. A peasant rebellion, one of the few successful such in history, established the swineherd Ivaylo as a Tsar. His short reign was essential in recovering—at least partially—the integrity of the Bulgarian state. A relatively thriving period followed after 1300, but ended in 1371, when factional divisions caused Bulgaria to split into three small Tsardoms. By 1396, they were subjugated by the Ottoman Empire. The Turks eliminated the Bulgarian system of nobility and ruling clergy, and Bulgaria remained an integral Ottoman Empire territory for the next 500 years.

With the decline of the Ottoman Empire after 1700, signs of revival started to emerge. The Bulgarian nobility had vanished, leaving an egalitarian peasant society with a small but growing urban middle class. By the 19th century, the Bulgarian National Revival became a key component of the struggle for independence, which would culminate in the failed April uprising in 1876, which prompted the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and the subsequent Liberation of Bulgaria. The initial Treaty of San Stefano was rejected by the Great Powers, and the following Treaty of Berlin limited Bulgaria's territories to Moesia and the region of Sofia. This left many ethnic Bulgarians out of the borders of the new state, which defined Bulgaria's militaristic approach to regional affairs and its allegiance to Germany in both World Wars.

After World War II, Bulgaria became a Communist state, with Todor Zhivkov serving as General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party for a period of 35 years, sparking rapid economic development, increased life expectancies, and a heavier focus on industry. Bulgaria's economic advancement during the era came to an end in the 1980s, and the collapse of the Communist system in Eastern Europe marked a turning point for the country's development. A series of crises in the 1990s left much of Bulgaria's industry and agriculture in shambles, although a period of relative stabilization began with the election of Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha as prime minister in 2001. Bulgaria joined NATO in 2004 and the European Union in 2007.

Prehistory

The earliest human remains found in Bulgaria were excavated in the Kozarnika cave, with an approximate age of 1,6 million BC. This cave probably keeps the earliest evidence of human symbolic behaviour ever found. A fragmented pair of human jaws, which are 44,000 years old, were found in Bacho Kiro cave, but it is disputed whether these early humans were in fact Homo sapiens or Neanderthals.[6]

The earliest dwellings in Bulgaria – the Stara Zagora Neolithic dwellings – date from 6,000 BC and are amongst the oldest human-made structures yet discovered.[7] By the end of the neolithic, the Karanovo, Hamangia and Vinča cultures developed on what is today Bulgaria, southern Romania and eastern Serbia.[8][9] The earliest known town in Europe, Solnitsata, was located in present-day Bulgaria.[10] The Durankulak lake settlement in Bulgaria commenced on a small island, approximately 7000 BC and around 4700/4600 BC the stone architecture was already in general use and became a characteristic phenomenon that was unique in Europe.

The eneolithic Varna culture (5000 BC)[11] represents the first civilization with a sophisticated social hierarchy in Europe. The centrepiece of this culture is the Varna Necropolis, discovered in the early 1970s. It serves as a tool in understanding how the earliest European societies functioned,[12] principally through well-preserved ritual burials, pottery, and golden jewellery. The golden rings, bracelets and ceremonial weapons discovered in one of the graves were created between 4,600 and 4200 BC, which makes them the oldest gold artefacts yet discovered anywhere in the world.[13]

Some of the earliest evidence of grape cultivation and livestock domestication is associated with the Bronze Age Ezero culture.[14] The Magura Cave drawings date from the same era, although the exact years of their creation cannot be pin-pointed.

Antiquity

The Thracians

The first people to leave lasting traces and cultural heritage throughout the region were the Thracians. Their origin remains obscure. It is generally proposed that a proto-Thracian people developed from a mixture of indigenous peoples and Indo-Europeans from the time of Proto-Indo-European expansion in the Early Bronze Age[15] when the latter, around 1500 BC, conquered the indigenous peoples.[16] Thracian craftsmen inherited the skills of the indigenous civilisations before them, especially in gold working.[17]

The Thracians were generally disorganized, but had an advanced culture despite the lack of their own proper script, and gathered powerful military forces when their divided tribes formed unions under the pressure of external threats. They never achieved any form of unity beyond short, dynastic rules at the height of the Greek classical period. Similar to the Gauls and other Celtic tribes, most Thracians are thought to have lived simply in small fortified villages, usually on hilltops. Although the concept of an urban center was not developed until the Roman period, various larger fortifications which also served as regional market centers were numerous. Yet, in general, despite Greek colonization in such areas as Byzantium, Apollonia and other cities, the Thracians avoided urban life.

Early Ancient Greek coastal colonisation

The first Greek colonies in Thrace were founded in the 8th century BC.[18]

Achaemenid Persian invasions

Ever since the Macedonian king Amyntas I surrendered his country to the Persians in about 512-511 BC, Macedonians and Persians were strangers no more.[2] Subjugation of Macedonia was part of Persian military operations initiated by Darius the Great (521–486 BC). In 513 BC - after immense preparations - a huge Achaemenid army invaded the Balkans and tried to defeat the European Scythians roaming to the north of the Danube river.[2] Darius' army subjugated several Thracian peoples, and virtually all other regions that touch the European part of the Black Sea, such as parts of nowadays Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, before it returned to Asia Minor.[2][20] Darius left in Europe one of his commanders named Megabazus whose task was to accomplish conquests in the Balkans.[2] The Persian troops subjugated gold-rich Thrace, the coastal Greek cities, as well as defeating and conquering the powerful Paeonians.[2][21][22] Finally, Megabazus sent envoys to Amyntas, demanding acceptation of Persian domination, which the Macedonian accepted.[2] Following the Ionian Revolt, the Persian hold over the Balkans loosened, but was firmly restored in 492 BC through the campaigns of Mardonius.[2] The Balkans, including what is nowadays Bulgaria, provided many soldiers for the multi ethnic Achaemenid army. Several Thracian treasures dating from the Persian rule in Bulgaria have been found.[23] Most of what is today eastern Bulgaria remained firmly under the Persian sway until 479 BC.[2][24] The Persian garrison at Doriscus in Thrace held out for many years even after the Persian defeat, and reportedly never surrendered. It remained as the last Persian stronghold in Europe.[25]

Odrysian kingdom (c. 480 BC - 30 BC)

Thracian tribes remained divided and most of them fell under nominal Persian rule from the late 6th century till the first half of the 5th century,[26] until King Teres united most of them in the Odrysian kingdom around 470 BC, probably after the Persian defeat in Greece,[27] which later peaked under the leadership of King Sitalces (431–424 BC) and of Cotys I (383–359 BC). At the commencement of the Peloponnesian war Sitalces entered into alliance with the Athenians, and in 429 BC he invaded Macedon (then ruled by Perdiccas II) with a vast army that included 150,000 warriors from independent Thracian tribes. Cotys I on the other hand, went to war with the Athenians for the possession of the Thracian Chersonese.

Ancient Macedon invasions

Thereafter the Macedonian Empire incorporated the Odrysian kingdom[28] and Thracians became an inalienable component in the extra-continental expeditions of both Philip II and Alexander III (the Great).

Ancient Celtic invasions

.png.webp)

In 298 BC, Celtic tribes reached what is today Bulgaria and clashed with the forces of Macedonian king Cassander in Mount Haemos (Stara Planina). The Macedonians won the battle, but this did not stop the Celtic advancement. Many Thracian communities, weakened by the Macedonian occupation, fell under Celtic dominance.[29]

In 279 BC, one of the Celtic armies, led by Comontorius, attacked Thrace and succeeded in conquering it. Comontorius established the kingdom of Tylis in what is now eastern Bulgaria.[30] The modern-day village of Tulovo bears the name of this relatively short-lived kingdom. Cultural interactions between Thracians and Celts are evidenced by several items containing elements of both cultures, such as the chariot of Mezek and almost certainly the Gundestrup cauldron.[31]

Tylis lasted until 212 BC, when the Thracians managed to regain their dominant position in the region and disbanded it.[32] Small bands of Celts survived in Western Bulgaria. One such tribe were the serdi, from which Serdica - the ancient name of Sofia - originates.[33] Even though the Celts remained in the Balkans for more than a century, their influence on the peninsula was modest.[30] By the end of the 3rd century, a new threat appeared for the people of the Thracian region in the shape of the Roman Empire.

Roman period

.jpg.webp)

In 188 BC, the Romans invaded Thrace, and warfare continued until 46 AD when Rome finally conquered the region.

Sapaean Thracian kingdom (Roman vassal state) (1st century BC - 46 AD)

The Sapaean kingdom was an ancient Thracian state in the southeastern Balkans that existed from the middle of the 1st century BC to 46 AD. Succeeding the Classical and Hellenistic era Odrysian kingdom of Thrace, it was dominated by the Sapaean tribe, who ruled from their capital Bizye in what is now northwestern Turkey. Initially only of limited relevance, its power grew significantly in the ancient Roman world as a client state of the late Roman Republic. After the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, Octavian (later emperor Augustus) installed a new dynasty that proved to be highly loyal and expansive. Conquering and ruling much of Thrace on behalf of the Roman Empire, it lasted until 46 AD, when Emperor Claudius annexed the kingdom and made Thracia into a Roman province.

Roman rule

In 46 AD, the Romans established the province of Thracia. By the 4th century, the Thracians had a composite indigenous identity, as Christian "Romans" who preserved some of their ancient pagan rituals. Thraco-Romans became a dominant group in the region, and eventually yielded several military commanders and emperors such as Galerius and Constantine I the Great. Urban centres became well-developed, especially the territories of Serdika, what is today Sofia, due to the abundance of mineral springs. The influx of immigrants from around the empire enriched the local cultural landscape; temples of Osiris and Isis have been discovered near the Black Sea coast.[34] Sometime before 300 AD, Diocletian further divided Thracia into four smaller provinces.

Migration Period (3rd century - 7th century)

In the 4th century, a group of Goths arrived in northern Bulgaria and settled in and around Nicopolis ad Istrum. There the Gothic bishop Ulfilas translated the Bible from Greek to Gothic, creating the Gothic alphabet in the process. This was the first book written in a Germanic language, and for this reason at least one historian refers to Ulfilas as "the father of Germanic literature".[35] The first Christian monastery in Europe was founded in 344 by Saint Athanasius near modern-day Chirpan following the Council of Serdica.[36]

Due to the rural nature of the local population, Roman control of the region remained weak. In the 5th century, Attila's Huns attacked the territories of today's Bulgaria and pillaged many Roman settlements. By the end of the 6th century, Avars organized regular incursions into northern Bulgaria, which were a prelude to the en masse arrival of the Slavs.

During the 6th century, the traditional Greco-Roman culture was still influential, but Christian philosophy and culture were dominant and began to replace it.[37] From the 7th century, Greek became the predominant language in the Eastern Roman Empire's administration, Church and society, replacing Latin.[38]

Gothic Invasions 250-251

Gothic Invasions 250-251 Gothic Invasions 267-269

Gothic Invasions 267-269 Gothic Invasions 376-382

Gothic Invasions 376-382 The Bulgar and Slavic migrations 6th - 7th century

The Bulgar and Slavic migrations 6th - 7th century

Slavs

The Slavs emerged from their original homeland (most commonly thought to have been in Eastern Europe) in the early 6th century and spread to most of eastern Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, thus forming three main branches - the West Slavs, the East Slavs and the South Slavs. The easternmost South Slavs settled on the territory of modern Bulgaria during the 6th century.

Most of the Thracians were eventually Hellenized or Romanized, with some exceptions surviving in remote areas until the 5th century.[39][40] A portion of the eastern South Slavs assimilated most of them, before the Bulgar élite incorporated these peoples into the First Bulgarian Empire.[41]

Bulgars

The Bulgars were a semi-nomadic people of Turkic descent, originally from Central Asia, who from the 2nd century onwards dwelled in the steppes north of the Caucasus and around the banks of river Volga (then Itil). A branch of them gave rise to the First Bulgarian Empire. The Bulgars were governed by hereditary khans. There were several aristocratic families whose members, bearing military titles, formed a governing class. Bulgars were polytheistic, but chiefly worshiped the supreme deity Tangra.

Old Great Bulgaria

In 632, Khan Kubrat united the three largest Bulgar tribes: the Kutrigur, the Utugur and the Onogonduri, thus forming the country that now historians call Great Bulgaria (also known as Onoguria). This country was situated between the lower course of the Danube river to the west, the Black Sea and the Azov Sea to the south, the Kuban river to the east and the Donets river to the north. The capital was Phanagoria, on the Azov.

In 635, Kubrat signed a peace treaty with emperor Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire, expanding the Bulgar kingdom further into the Balkans. Later, Kubrat was crowned with the title Patrician by Heraclius. The kingdom never survived Kubrat's death. After several wars with the Khazars, the Bulgars were finally defeated and they migrated to the south, to the north, and mainly to the west into the Balkans, where most of the other Bulgar tribes were living, in a state vassal to the Byzantine Empire since the 5th century.

One of the successors of Khan Kubrat, Kotrag led nine Bulgar tribes to the north along the banks of the river Volga in what is today Russia, creating the Kingdom of the Volga Bulgars in the late 7th century. This kingdom later became the trade and cultural centre of the north, because it stood on a very strategic position creating a monopoly over the trade among the Arabs, the Norse and the Avars. The Volga Bulgars were the first to ever defeat the Mongolic horde and protected Europe for decades, but after countless Mongol invasions the Kingdom of the Volga Bulgars was destroyed and most of its citizens slaughtered or sold as slaves in Asia.

Another successor of Khan Kubrat, Asparuh (Kotrag's brother) moved west, occupying today's southern Bessarabia. After a successful war with Byzantium in 680, Asparuh's khanate conquered initially Scythia Minor and was recognised as an independent state under the subsequent treaty signed with the Byzantine Empire in 681. That year is usually regarded as the year of the establishment of present-day Bulgaria and Asparuh is regarded as the first Bulgarian ruler.

Another Bulgar horde, led by Asparuh's brother Kuber, came to settle in Pannonia and later into the region of Macedonia.[42][43]

First Bulgarian Empire (681–1018)

Under the reign of Asparuh Bulgaria expanded southwest after the Battle of Ongal and Danubian Bulgaria was created.

During the Late Roman Empire, several Roman provinces covered the territory that comprises present-day Bulgaria: Scythia (Scythia Minor), Moesia (Upper and Lower), Thrace, Macedonia (First and Second), Dacia (Coastal and Inner, both south of Danube), Dardania, Rhodope and Haemismontus, and had a mixed population of Byzantine Greeks, Thracians and Dacians, most of whom spoke either Greek or variants of Vulgar Latin. Several consecutive waves of Slavic migration throughout the 6th and the early 7th centuries led to a dramatic change of the demographics of the region and its almost complete Slavicisation.

The son and heir of Asparuh Tervel becomes ruler in the beginning of 8th century when the Byzantine emperor Justinian II asked Tervel for assistance in recovering his throne, for which Tervel received the region Zagore from the Empire and was paid large quantities of gold. He also received the Byzantine title "Caesar". Years later, the emperor decided to betray and attack Bulgaria, but his army was crushed in the battle of Anhialo. After the death of Justinian II, the Bulgarians continue their crusades against the empire and in 716 they reach Constantinople. The threat of both the Bulgarians and the Arab menace in the east, force the new emperor Theodosius III, to sign a peace treaty with Tervel. The successor, Leo III the Isaurian has to deal with an army of 100,000 Arabs led by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik and a fleet of 2,500 ships that are laying siege on Constantinople in the year 717. Relying on his treaty with Bulgaria, the emperor asks Khan Tervel to help him deal with the Arab invasion. Tervel accepts and the Arabs are decimated outside the walls of the city. The fleet is heavily damaged with the help of Greek fire. The remaining ships are destroyed by a storm, in an attempt to flee. So the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople ended. After the reign of Tervel, there were frequent changes in the ruling houses, which lead to instability and political crisis.

Decades later, in 768, Telerig of the house Dulo, ruled Bulgaria. His military campaign against Constantine V in the year 774, proved to be unsuccessful. Thrilled with his success against Telerig, the Byzantine Emperor dispatched a fleet 2,000 ships loaded with horsemen. This expedition proved to be a failure, because of strong northern winds near Mesembria. Telerig was aware of the increased presence of spies in the capital Pliska. To decrease this Byzantine influence, he sent a letter to the emperor in which he asks for refuge in Constantinople and wants to know which Byzantine spies can help him. Knowing their names, he slaughters every agent in the capital. His rule marked the end of the political crisis.

Under the reign of Krum (802–814) Bulgaria expanded vastly north-west and south, occupying the lands between the middle Danube and Moldova rivers, all of present-day Romania, Sofia in 809 and Adrianople in 813, and threatening Constantinople itself. Krum implemented law reform intending to reduce poverty and strengthen social ties in his vastly enlarged state.

During the reign of Khan Omurtag (814–831), the northwestern boundaries with the Frankish Empire were firmly settled along the middle Danube. A magnificent palace, pagan temples, ruler's residence, fortress, citadel, water mains and baths were built in the Bulgarian capital Pliska, mainly of stone and brick.

Omurtag pursued policy of repression against Christians. Menologion of Basil II, glorifies Emperor Basil II showing him as a warrior defending Orthodox Christendom against the attacks of the Bulgarian Empire, whose attacks on Christians are graphically illustrated.

Christianization

Under Boris I, Bulgaria became officially Christian, and the Ecumenical Patriarch agreed to allow an autonomous Bulgarian Archbishop at Pliska. Missionaries from Constantinople, Cyril and Methodius, devised the Glagolitic alphabet, which was adopted in the Bulgarian Empire around 886. The alphabet and the Old Bulgarian language that evolved from Slavonic[44] gave rise to a rich literary and cultural activity centered around the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools, established by order of Boris I in 886.

In the early 9th century, a new alphabet — Cyrillic — was developed at the Preslav Literary School, adapted from the Glagolitic alphabet invented by Saints Cyril and Methodius.[45] An alternative theory is that the alphabet was devised at the Ohrid Literary School by Saint Climent of Ohrid, a Bulgarian scholar and disciple of Cyril and Methodius.

By the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Bulgaria extended to Epirus and Thessaly in the south, Bosnia in the west and controlled all of present-day Romania and eastern Hungary to the north reuniting with old roots. A Serbian state came into existence as a dependency of the Bulgarian Empire. Under Tsar Simeon I of Bulgaria (Simeon the Great), who was educated in Constantinople, Bulgaria became again a serious threat to the Byzantine Empire. His aggressive policy was aimed at displacing Byzantium as major partner of the nomadic polities in the area. By subverting the principles of Byzantine diplomacy and political culture, Simeon turned his own kingdom into a society-structuring factor in the nomadic world.[46][47]

Simeon hoped to take Constantinople and become emperor of both Bulgarians and Greeks, and fought a series of wars with the Byzantines through his long reign (893–927). At the end of his rule the front had reached the Peloponnese in the south, making it the most powerful state in contemporary Southeast Europe.[47] Simeon proclaimed himself "Tsar (Caesar) of the Bulgarians and the Romans", a title which was recognised by the Pope, but not by the Byzantine Emperor. The capital Preslav was said to rival Constantinople,[48][49] the new independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church became the first new patriarchate besides the Pentarchy and Bulgarian translations of Christian texts spread all over the Slavic world of the time.[50]

Bogomilism

During the reign of Emperor Peter I (r. 927–969) a heretical movement known as Bogomilism arose in Bulgaria. The heresy was named after its founder the priest Bogomil whose name can be translated as dear (mil) to God (Bog). The main sources about Bogomilism in Bulgaria come from a letter of the Ecumenical Patriarch Theophylact of Constantinople to Peter I (c. 940), a treatise by Cosmas the Priest (c. 970) and the anti-Bogomil council of Emperor Boril of Bulgaria (1211).[51] Bogomilism was a neo-Gnostic and dualist sect that believed that God had two sons, Jesus Christ and Satan, that represented the two principles good and evil.[52] God had created light and the invisible world, while Satan rebelled and created darkness, the material world and man.[52][53]

Decline

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria was weakened by external and internal wars with Croatians, Magyars, Pechenegs and Serbs and the spread of the Bogomil heresy.[54][55] Two consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions resulted in the seizure of the capital Preslav by the Byzantine army in 971.[56] Under Samuil, Bulgaria somewhat recovered from these attacks and managed to conquer Serbia and Duklja.[57]

In 986, the Byzantine emperor Basil II undertook a campaign to conquer Bulgaria. After a war lasting several decades he inflicted a decisive defeat upon the Bulgarians in 1014 and completed the campaign four years later. In 1018, after the death of the last Bulgarian Tsar - Ivan Vladislav, most of Bulgaria's nobility chose to join the Eastern Roman Empire.[58] However, Bulgaria lost its independence and remained subject to Byzantium for more than a century and a half. With the collapse of the state, the Bulgarian church fell under the domination of Byzantine ecclesiastics who took control of the Ohrid Archbishopric.[59]

Bulgaria under Byzantine rule (1018–1185)

No evidence remains of major resistance or any uprising of the Bulgarian population or nobility in the first decade after the establishment of Byzantine rule. Given the existence of such irreconcilable opponents to the Byzantines as Krakra, Nikulitsa, Dragash and others, such apparent passivity seems difficult to explain. Some historians[60] explain this as a consequence of the concessions that Basil II granted the Bulgarian nobility to gain their allegiance.

Basil II guaranteed the indivisibility of Bulgaria in its former geographic borders and did not officially abolish the local rule of the Bulgarian nobility, who became part of Byzantine aristocracy as archons or strategoi. Secondly, special charters (royal decrees) of Basil II recognised the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and set up its boundaries, securing the continuation of the dioceses already existing under Samuil, their property and other privileges.[61]

After the death of Basil II the empire entered into a period of instability. In 1040, Peter Delyan organized a large-scale rebellion, but failed to restore the Bulgarian state and was killed. Shortly after, the Komnenos dynasty came into succession and halted the decline of the empire. During this time the Byzantine state experienced a century of stability and progress.

In 1180 the last of the capable Komnenoi, Manuel I Komnenos, died and was replaced by the relatively incompetent Angeloi dynasty, allowing some Bulgarian nobles to organize an uprising. In 1185 Peter and Asen, leading nobles of supposed and contested Bulgarian, Cuman, Vlach or mixed origin, led a revolt against Byzantine rule and Peter declared himself Tsar Peter II. The following year, the Byzantines were forced to recognize Bulgaria's independence. Peter styled himself "Tsar of the Bulgars, Greeks and Wallachians".

Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396)

.png.webp)

Resurrected Bulgaria occupied the territory between the Black Sea, the Danube and Stara Planina, including a part of eastern Macedonia, Belgrade and the valley of the Morava. It also exercised control over Wallachia[62] Tsar Kaloyan (1197–1207) entered a union with the Papacy, thereby securing the recognition of his title of "Rex" (King) although he desired to be recognized as "Emperor" or "Tsar" of Bulgarians and Vlachs. He waged wars on the Byzantine Empire and (after 1204) on the Knights of the Fourth Crusade, conquering large parts of Thrace, the Rhodopes, Bohemia, and Moldavia as well as the whole of Macedonia.

In the Battle of Adrianople in 1205, Kaloyan defeated the forces of the Latin Empire and thus limited its power from the very first year of its establishment. The power of the Hungarians and to some extent the Serbs prevented significant expansion to the west and north-west. Under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), Bulgaria once again became a regional power, occupying Belgrade and Albania. In an inscription from Turnovo in 1230 he entitled himself "In Christ the Lord faithful Tsar and autocrat of the Bulgarians, son of the old Asen".

The Bulgarian Orthodox Patriarchate was restored in 1235 with approval of all eastern Patriarchates, thus putting an end to the union with the Papacy. Ivan Asen II had a reputation as a wise and humane ruler, and opened relations with the Catholic west, especially Venice and Genoa, to reduce the influence of the Byzantines over his country. Tarnovo became a major economic and religious centre—a "Third Rome", unlike the already declining Constantinople.[63] As Simeon the Great during the first empire, Ivan Asen II expanded the territory to the coasts of three seas (Adriatic, Aegean and Black), annexed Medea - the last fortress before the walls of Constantinople, unsuccessfully besieged the city in 1235 and restored the destroyed since 1018 Bulgarian Patriarchate.

The country's military and economic might declined after the end of the Asen dynasty in 1257, facing internal conflicts, constant Byzantine and Hungarian attacks and Mongol domination.[41][64] Tsar Teodore Svetoslav (reigned 1300–1322) restored Bulgarian prestige from 1300 onwards, but only temporarily. Political instability continued to grow, and Bulgaria gradually began to lose territory. This led to a peasant rebellion led by the swineherd Ivaylo, who eventually managed to defeat the Tsar's forces and ascend the throne.

Ottoman incursions

A weakened 14th-century Bulgaria faced a new threat from the south, the Ottoman Turks, who crossed into Europe in 1354. By 1371, factional divisions between the feudal landlords and the spread of Bogomilism had caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to split into three small tsardoms—Vidin, Tarnovo and Karvuna—and several semi-independent principalities that fought among themselves, and also with Byzantines, Hungarians, Serbs, Venetians and Genoese.

The Ottomans faced little resistance from these divided and weak Bulgarian states. In 1362 they captured Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and in 1382 they took Sofia. The Ottomans then turned their attentions to the Serbs, whom they routed at Kosovo Polje in 1389. In 1393 the Ottomans occupied Tarnovo after a three-month siege. In 1396 the Tsardom of Vidin was also invaded, bringing the Second Bulgarian Empire and Bulgarian independence to an end.

Bulgaria under Ottoman rule (1396–1878)

In 1393, the Ottomans captured Tarnovo, the capital of the Second Bulgarian Empire, after a three-month siege. In 1396, the Vidin Tsardom fell after the defeat of a Christian crusade at the Battle of Nicopolis. With this the Ottomans finally subjugated and occupied Bulgaria.[39] [65][66] A Polish-Hungarian crusade commanded by Władysław III of Poland set out to free Bulgaria and the Balkans in 1444, but the Turks emerged victorious at the battle of Varna.

The new authorities dismantled Bulgarian institutions and merged the separate Bulgarian Church into the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople (although a small, autocephalous Bulgarian archbishopric of Ohrid survived until January 1767). Turkish authorities destroyed most of the medieval Bulgarian fortresses to prevent rebellions. Large towns and the areas where Ottoman power predominated remained severely depopulated until the 19th century.[67]

.png.webp)

The Ottomans did not normally require the Christians to become Muslims. Nevertheless, there were many cases of forced individual or mass Islamization, especially in the Rhodopes. Bulgarians who converted to Islam, the Pomaks, retained Bulgarian language, dress and some customs compatible with Islam.[39][66].

The Ottoman system began declining by the 17th century and at the end of the 18th had all but collapsed. Central government weakened over the decades and this had allowed a number of local Ottoman holders of large estates to establish personal ascendancy over separate regions.[68] During the last two decades of the 18th and first decades of the 19th centuries the Balkan Peninsula dissolved into virtual anarchy.[39][69]

Bulgarian tradition calls this period the kurdjaliistvo: armed bands of Turks called kurdjalii plagued the area. In many regions, thousands of peasants fled from the countryside either to local towns or (more commonly) to the hills or forests; some even fled beyond the Danube to Moldova, Wallachia or southern Russia.[39][69] The decline of Ottoman authorities also allowed a gradual revival of Bulgarian culture, which became a key component in the ideology of national liberation.

Conditions gradually improved in certain areas in the 19th century. Some towns — such as Gabrovo, Tryavna, Karlovo, Koprivshtitsa, Lovech, Skopie — prospered. The Bulgarian peasants actually possessed their land, although it officially belonged to the sultan. The 19th century also brought improved communications, transportation and trade. The first factory in the Bulgarian lands opened in Sliven in 1834 and the first railway system started running (between Rousse and Varna) in 1865.

Bulgarian nationalism was emergent in the early 19th century under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French Revolution, mostly via Greece. The Greek revolt against the Ottomans which began in 1821 also influenced the small Bulgarian educated class. But Greek influence was limited by the general Bulgarian resentment of Greek control of the Bulgarian Church and it was the struggle to revive an independent Bulgarian Church which first roused Bulgarian nationalist sentiment.

In 1870, a Bulgarian Exarchate was created by a firman and the first Bulgarian Exarch, Antim I, became the natural leader of the emerging nation. The Constantinople Patriarch reacted by excommunicating the Bulgarian Exarchate, which reinforced their will for independence. A struggle for political liberation from the Ottoman Empire emerged in the face of the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Internal Revolutionary Organisation led by liberal revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski, Hristo Botev and Lyuben Karavelov.

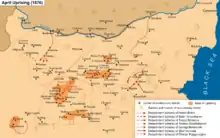

April Uprising and Russo-Turkish War (1870s)

_03.jpg.webp)

In April 1876, the Bulgarians revolted in the April Uprising. The revolt was poorly organized and started before the planned date. It was largely confined to the region of Plovdiv, though certain districts in northern Bulgaria, in Macedonia, and in the area of Sliven also took part. The uprising was crushed by the Ottomans, who brought in irregular troops (bashi-bazouks) from outside the area. Countless villages were pillaged and tens of thousands of people were massacred, the majority of them in the insurgent towns of Batak, Perushtitsa, and Bratsigovo, all in the area of Plovdiv.

The massacres aroused a broad public reaction among liberal Europeans such as William Ewart Gladstone, who launched a campaign against the "Bulgarian Horrors". The campaign was supported by many European intellectuals and public figures. The strongest reaction, however, came from Russia. The enormous public outcry which the April Uprising had caused in Europe led to the Constantinople Conference of the Great Powers in 1876–77.

Turkey's refusal to implement the decisions of the conference gave Russia a long-waited chance to realise her long-term objectives with regard to the Ottoman Empire. Having its reputation at stake, Russia declared war on the Ottomans in April 1877. The Bulgarians also fought alongside the advancing Russians. Russia established a provisional government in Bulgaria. The Russian army and the Bulgarian Opalchentsi decisively defeated the Ottomans at Shipka Pass and Pleven. By January 1878 they had liberated much of the Bulgarian lands. (See Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878).)

Third Bulgarian State (1878–1946)

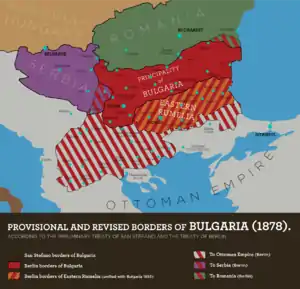

The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on 3 March 1878 and set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality on the territories of the Second Bulgarian Empire, including the regions of Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia,[70][71] though the state was de jure only autonomous but de facto functioned independently. However, trying to preserve the balance of power in Europe and fearing the establishment of a large Russian client state in the Balkans, the other Great Powers were reluctant to agree to the treaty.[70]

As a result, the Treaty of Berlin (1878), under the supervision of Otto von Bismarck of Germany and Benjamin Disraeli of Britain, revised the earlier treaty, and scaled back the proposed Bulgarian state. The new territory of Bulgaria was limited between the Danube and the Stara Planina range, with its seat at the old Bulgarian capital of Veliko Turnovo and including Sofia. This revision left large populations of ethnic Bulgarians outside the new country and defined Bulgaria's militaristic approach to foreign affairs and its participation in four wars during the first half of the 20th century.[70][72][73]

Alexander of Battenberg, a German with close ties to the Russian Tsar, was the first prince (knyaz) of modern Bulgaria from 1879. Everyone had assumed Bulgaria would become a Russian ally. To the contrary, it became a bulwark against Russian expansion, and cooperated with the British.[74] Bulgaria was attacked by Serbia in 1885, but defeated the invaders. It thereby gained respect from the great powers and defied Russia. In response Russia secured the abdication of Prince Alexander in 1886.[75]

Stefan Stambolov (1854-1895) served 1886-1894 first as regent and then prime minister for the new ruler, Ferdinand I of Bulgaria (prince 1887–1908, tsar 1908-1918). Stambolov believed that Russia's liberation of Bulgaria from Turkish rule had been an attempt by Czarist Russia to turn Bulgaria into its protectorate. His policy was characterized by the goal of preserving Bulgarian independence at all costs, working with both the Liberal majority and Conservative minority parties. During his leadership Bulgaria was transformed from an Ottoman province into a modern European state. Stambolov launched a new course in Bulgarian foreign policy, independent of the interests of any great power. His main foreign policy objective was the unification of the Bulgarian nation into a nation-state consisting of all the territories of the Bulgarian Exarchate granted by the Sultan in 1870. Stambolov established close connections with the Sultan in order to enliven Bulgarian national spirit in Macedonia and to oppose Russian-backed Greek and Serbian propaganda. As a result of Stambolov's tactics, the Sultan recognised Bulgarians as the predominant people in Macedonia and gave a green light to the creation of a strong church and cultural institutions. Stambolov negotiated loans with western European countries to develop the economic and military strength of Bulgaria. In part, this was motivated by his desire to create a modern army which could secure all of the national territory. His approach toward western Europe was one of diplomatic manoeuvring. He understood the interests of the Austrian Empire in Macedonia and warned his diplomats accordingly. His domestic policy was distinguished by the defeat of terrorist groups sponsored by Russia, the strengthening of the rule of law, and rapid economic and educational growth, leading to progressive social and cultural change, and development of a modern army capable of protecting Bulgaria's independence. Stambolov was aware that Bulgaria had to be politically, militarily, and economically strong to achieve national unification. He mapped out the political course which turned Bulgaria into a strong regional power, respected by the great powers of the day. However, Bulgaria's regional leadership was short-lived. After Stambolov's death the independent course of his policy was abandoned.[76]

Bulgaria emerged from Turkish rule as a poor, underdeveloped agricultural country, with little industry or tapped natural resources. Most of the land was owned by small farmers, with peasants comprising 80% of the population of 3.8 million in 1900. Agrarianism was the dominant political philosophy in the countryside, as the peasantry organized a movement independent of any existing party. In 1899, the Bulgarian Agrarian Union was formed, bringing together rural intellectuals such as teachers with ambitious peasants. It promoted modern farming practices, as well as elementary education.[77]

The government promoted modernization, with special emphasis on building a network of elementary and secondary schools. By 1910, there were 4,800 elementary schools, 330 lyceums, 27 post-secondary educational institutions, and 113 vocational schools. From 1878 to 1933, France funded numerous libraries, research institutes, and Catholic schools throughout Bulgaria. In 1888, a university was established. It was renamed the University of Sofia in 1904, where the three faculties of history and philology, physics and mathematics, and law produced civil servants for national and local government offices. It became the center of German and Russian intellectual, philosophical and theological influences.[78]

The first decade of the century saw sustained prosperity, with steady urban growth. The capital of Sofia grew by a factor of 600% - from 20,000 population in 1878 to 120,000 in 1912, primarily from peasants who arrived from the villages to become laborers, tradesman and office seekers. Macedonians used Bulgaria as a base, beginning in 1894, to agitate for independence from the Ottoman Empire. They launched a poorly planned uprising in 1903 that was brutally suppressed, and led to tens of thousands of additional refugees pouring into Bulgaria.[79]

The Balkan Wars

In the years following independence, Bulgaria became increasingly militarized and was often referred to as "the Balkan Prussia", with regard to its desire to revise the Treaty of Berlin through warfare.[80][81][82] The partition of territories in the Balkans by the Great Powers without regard to ethnic composition led to a wave of discontent not only in Bulgaria, but also in its neighbouring countries. In 1911, Nationalist Prime Minister Ivan Geshov formed an alliance with Greece and Serbia to jointly attack the Ottomans and revise the existing agreements around ethnic lines.[83]

In February 1912 a secret treaty was signed between Bulgaria and Serbia and in May 1912 a similar agreement was sealed with Greece. Montenegro was also brought into the pact. The treaties provided for the partition of the regions of Macedonia and Thrace between the allies, although the lines of partition were left dangerously vague. After the Ottoman Empire refused to implement reforms in the disputed areas, the First Balkan War broke out in October 1912 at a time when the Ottomans were tied down in a major war with Italy in Libya. The allies easily defeated the Ottomans and seized most of its European territory.[83]

Bulgaria sustained the heaviest casualties of any of the allies while also making the largest territorial claims. The Serbs in particular did not agree and refused to vacate any of the territory they had seized in northern Macedonia (that is, the territory roughly corresponding to the modern Republic of North Macedonia), saying that the Bulgarian army had failed to accomplish its pre-war goals at Adrianople (to capture it without Serbian help) and that the pre-war agreement on the division of Macedonia had to be revised. Some circles in Bulgaria inclined toward going to war with Serbia and Greece on this issue.

In June 1913, Serbia and Greece formed a new alliance against Bulgaria. The Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pasic promised Greece Thrace to Greece [no reference] if it helped Serbia defend the territory it had captured in Macedonia; the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos agreed [no reference]. Seeing this as a violation of the pre-war agreements, and privately encouraged by Germany and Austria-Hungary, Tsar Ferdinand declared war on Serbia and Greece on June 29.

The Serbian and Greek forces were initially beaten back from Bulgaria's western border, but they quickly gained the advantage and forced Bulgaria to retreat. The fighting was very harsh, with many casualties, especially during the key Battle of Bregalnitsa. Soon afterward, the Romania entered the war on the side of Greece and Serbia, attacking Bulgaria from the north. The Ottoman Empire saw this as an opportunity to regain its lost territories and also attacked from the south-east.

Facing war on three different fronts, Bulgaria sued for peace. It was forced to relinquish most of its territorial acquisitions in Macedonia to Serbia and Greece, Adrianapole to the Ottoman Empire, and the region of Southern Dobruja to Romania. The two Balkan wars greatly destabilized Bulgaria, stopping its hitherto steady economic growth, and leaving 58,000 dead and over 100,000 wounded. The bitterness at the perceived betrayal of its former allies empowered political movements who demanded the restoration of Macedonia to Bulgaria.[84]

World War I

.jpg.webp)

In the aftermath of the Balkan Wars Bulgarian opinion turned against Russia and the Western powers, by whom the Bulgarians felt betrayed. The government of Vasil Radoslavov aligned Bulgaria with the German Empire and Austria-Hungary, even though this meant becoming an ally of the Ottomans, Bulgaria's traditional enemy. But Bulgaria now had no claims against the Ottomans, whereas Serbia, Greece and Romania (allies of Britain and France) held lands perceived in Bulgaria as Bulgarian.

Bulgaria sat out the first year of World War I recuperating from the Balkan Wars.[85] Germany and Austria realized they needed Bulgaria's help in order to defeat Serbia militarily thereby opening supply lines from Germany to Turkey and bolstering the Eastern Front against Russia. Bulgaria insisted on major territorial gains, especially Macedonia, which Austria was reluctant to grant until Berlin insisted. Bulgaria also negotiated with the Allies, who offered somewhat less generous terms. The Tsar decided to go with Germany and Austria and signed an alliance with them in September 1915, along with a special Bulgarian-Turkish arrangement. It envisioned that Bulgaria would dominate the Balkans after the war.[86]

Bulgaria, which had the land force in the Balkans, declared war on Serbia in October 1915. Britain, France and Italy responded by declaring war on Bulgaria. In alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottomans, Bulgaria won military victories against Serbia and Romania, occupying much of Macedonia (taking Skopje in October), advancing into Greek Macedonia, and taking Dobruja from Romania in September 1916. Thus Serbia was temporarily knocked out of the war, and Turkey was temporarily rescued from collapse.[87] By 1917, Bulgaria fielded more than a quarter of its 4.5 million population in a 1,200,000-strong army,[88][89] and inflicted heavy losses on Serbia (Kaymakchalan), Great Britain (Doiran), France (Monastir), the Russian Empire (Dobrich) and the Kingdom of Romania (Tutrakan).

However, the war soon became unpopular with most Bulgarians, who suffered great economic hardship and also disliked fighting their fellow Orthodox Christians in alliance with the Muslim Ottomans. The Russian Revolution of February 1917 had a great effect in Bulgaria, spreading anti-war and anti-monarchist sentiment among the troops and in the cities. In June Radoslavov's government resigned. Mutinies broke out in the army, Stamboliyski was released and a republic was proclaimed.

Interwar years

In September 1918, Tsar Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his son Boris III in order to head off anti-monarchic revolutionary tendencies. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919) Bulgaria ceded its Aegean coastline to Greece, recognized the existence of Yugoslavia, ceded nearly all of its Macedonian territory to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, and had to give Dobruja back to Romania. The country had to reduce its army to no more than 22,000 men and pay reparations exceeding $400 million. Bulgarians generally refer to the results of the treaty as the "Second National Catastrophe."[90]

Elections in March 1920 gave the Agrarians a large majority and Aleksandar Stamboliyski formed Bulgaria's first peasant government. He faced huge social problems, but succeeded in carrying out many reforms, although opposition from the middle and upper classes, the landlords and officers of the army remained powerful. In March 1923, Stamboliyski signed an agreement with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia recognising the new border and agreeing to suppress Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), which favoured a war to regain Macedonia from Yugoslavia.[91]

This triggered a nationalist reaction and the coup d'état of 9 June 1923 eventually resulted in Stamboliykski's assassination. An extreme right-wing government under Aleksandar Tsankov took power, backed by the army and VMRO, which waged a White terror against Agrarians and Communists. In 1926, after the brief War of the Stray Dog, the Tsar persuaded Tsankov to resign, a more moderate government under Andrey Lyapchev took office and an amnesty was proclaimed, although the Communists remained banned. A popular alliance, including the re-organised Agrarians, won the elections of 1931 under the name "Popular Bloc".[91]

In May 1934 another coup took place, removing the Popular Bloc from power and establishing an authoritarian military régime headed by Kimon Georgiev. A year later, Tsar Boris managed to remove the military régime from power, restoring a form of parliamentary rule (without the re-establishment of the political parties) and under his own strict control. The Tsar's regime proclaimed neutrality, but gradually Bulgaria gravitated into alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

World War II

Upon the outbreak of World War II, the government of the Kingdom of Bulgaria under Bogdan Filov declared a position of neutrality, being determined to observe it until the end of the war, but hoping for bloodless territorial gains, especially in the lands with a significant Bulgarian population occupied by neighbouring countries after the Second Balkan War and World War I. But it was clear that the central geopolitical position of Bulgaria in the Balkans would inevitably lead to strong external pressure by both sides of World War II.[92] Turkey had a non-aggression pact with Bulgaria.[93]

Bulgaria succeeded in negotiating a recovery of Southern Dobruja, part of Romania since 1913, in the Axis-sponsored Treaty of Craiova on 7 September 1940, which reinforced Bulgarian hopes for solving territorial problems without direct involvement in the war. However, Bulgaria was forced to join the Axis powers in 1941, when German troops that were preparing to invade Greece from Romania reached the Bulgarian borders and demanded permission to pass through Bulgarian territory. Threatened by direct military confrontation, Tsar Boris III had no choice but to join the fascist bloc, which was made official on 1 March 1941. There was little popular opposition, since the Soviet Union was in a non-aggression pact with Germany.[94] However the king refused to hand over the Bulgarian Jews to the Nazis, saving 50,000 lives.[95]

Bulgaria did not join the German invasion of the Soviet Union that began on 22 June 1941 nor did it declare war on the Soviet Union. However, despite the lack of official declarations of war by both sides, the Bulgarian Navy was involved in a number of skirmishes with the Soviet Black Sea Fleet, which attacked Bulgarian shipping. Besides this, Bulgarian armed forces garrisoned in the Balkans battled various resistance groups. The Bulgarian government was forced by Germany to declare a token war on the United Kingdom and the United States on 13 December 1941, an act which resulted in the bombing of Sofia and other Bulgarian cities by Allied aircraft.

On 23 August 1944, Romania left the Axis Powers and declared war on Germany, and allowed Soviet forces to cross its territory to reach Bulgaria. On 5 September 1944 the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria and invaded. Within three days, the Soviets occupied the northeastern part of Bulgaria along with the key port cities of Varna and Burgas. Meanwhile, on 5 of September, Bulgaria declared war on Nazi Germany. The Bulgarian Army was ordered to offer no resistance.[96]

On 9 September 1944 in a coup the government of Prime Minister Konstantin Muraviev was overthrown and replaced with a government of the Fatherland Front led by Kimon Georgiev. On 16 September 1944 the Soviet Red Army entered Sofia.[96] The Bulgarian Army marked several victories against the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen (at Nish), the 22nd Infantry Division (at Strumica) and other German forces during the operations in Kosovo and at Stratsin.[97][98]

People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1991)

During this period the country was known as the "People's Republic of Bulgaria" (PRB) and was ruled by the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP). The BCP transformed itself in 1990, changing its name to "Bulgarian Socialist Party".

Communist leader Dimitrov had been in exile, mostly in the Soviet Union, since 1923. Although Stalin executed many other exiles he was close to Dimitrov and gave him high positions. Dimitrov was arrested in Berlin and showed great courage during the Reichstag fire trial of 1933. Stalin made him head of the Comintern during the period of the Popular Front'.[99]

After 1944 he was also close to the Yugoslav Communist leader Tito and believed that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, as closely related South Slav peoples, should form a federation. This idea was not favoured by Stalin. There have long been suspicions that Dimitrov's sudden death in Moscow in July 1949 was not accidental, although this has never been proven. It coincided with Stalin's expulsion of Tito from the Cominform and was followed by a "Titoist" witch hunt in Bulgaria. This culminated in the show trial and execution of Deputy Prime Minister Traicho Kostov (died 16 December 1949). The elderly Prime Minister Vasil Kolarov (born 1877) died in January 1950 and power then passed to a Stalinist, Vulko Chervenkov (1900–1980).

Bulgaria's Stalinist phase lasted less than five years. Under his leadership, agriculture was collectivised and a massive industrialisation campaign was launched. Bulgaria adopted a centrally planned economy, similar to those in other COMECON states. In the mid-1940s, when collectivisation began, Bulgaria was a primarily agrarian state, with some 80% of its population located in rural areas.[100][101] In 1950 diplomatic relations with the U.S. were broken off. But Chervenkov's support base in the Communist Party was too narrow for him to survive long once his patron Stalin was gone. Stalin died in March 1953 and in March 1954 Chervenkov was deposed as Party Secretary with the approval of the new leadership in Moscow and replaced by Todor Zhivkov. Chervenkov stayed on as Prime Minister until April 1956, when he was dismissed and replaced by Anton Yugov.

Bulgaria experienced a rapid industrial development from the 1950s onwards. From the following decade, the country's economy appeared profoundly transformed. Although many difficulties remained, such as poor housing and inadequate urban infrastructure, modernisation was a reality. The country then turned to high technology, a sector which represented 14% of its GDP between 1985 and 1990. Its factories produce processors, hard disks, floppy disk drives and industrial robots.[102]

During the 1960s, Zhivkov initiated reforms and passed some market-oriented policies on an experimental level.[103] By the mid-1950s standards of living rose significantly, and in 1957 collective farm workers benefited from the first agricultural pension and welfare system in Eastern Europe.[104] Lyudmila Zhivkova, daughter of Todor Zhivkov, promoted Bulgaria's national heritage, culture and arts on a global scale.[105] An assimilation campaign of the late 1980s directed against ethnic Turks resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 Bulgarian Turks to Turkey,[106][107] which caused a significant drop in agricultural production due to the loss of labor force.[108]

Republic of Bulgaria

By the time the impact of Mikhail Gorbachev's reform program in the Soviet Union was felt in Bulgaria in the late 1980s, the Communists, like their leader, had grown too feeble to resist the demand for change for long. In November 1989 demonstrations on ecological issues were staged in Sofia and these soon broadened into a general campaign for political reform. The Communists reacted by deposing Zhivkov and replacing him by Petar Mladenov, but this gained them only a short respite.

In February 1990 the Communist Party voluntarily gave up its monopoly on power and in June 1990 the first free elections since 1931 were held. The result was a return to power by the Communist Party, now shorn of its hardliner wing and renamed the Bulgarian Socialist Party. In July 1991 a new Constitution was adopted, in which the system of government was fixed as parliamentary republic with a directly elected President and a Prime Minister accountable to the legislature.

Like the other post-Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, Bulgaria found the transition to capitalism more painful than expected. The anti-Communist Union of Democratic Forces (UDF) took office and between 1992 and 1994 the Berov Government carried through the privatisation of land and industry through the issue of shares in government enterprises to all citizens, but these were accompanied by massive unemployment as uncompetitive industries failed and the backward state of Bulgaria's industry and infrastructure were revealed. The Socialists portrayed themselves as the defender of the poor against the excesses of the free market.

The negative reaction against economic reform allowed Zhan Videnov of the BSP to take office in 1995. By 1996 the BSP government was also in difficulties and in the presidential election of that year the UDF's Petar Stoyanov was elected. In 1997 the BSP government collapsed and the UDF came to power. Unemployment, however, remained high and the electorate became increasingly dissatisfied with both parties.

On 17 June 2001, Simeon II, the son of Tsar Boris III and himself the former Head of state (as Tsar of Bulgaria from 1943 to 1946), won a narrow victory in elections. The Tsar's party — National Movement Simeon II ("NMSII") — won 120 of the 240 seats in Parliament. Simeon's popularity declined quickly during his four-year rule as Prime Minister and the BSP won the election in 2005, but could not form a single-party government and had to seek a coalition. In the parliamentary elections in July 2009, Boyko Borisov's right-centrist party Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria won nearly 40% of the votes.

Since 1989 Bulgaria has held multi-party elections and privatized its economy, but economic difficulties and a tide of corruption have led over 800,000 Bulgarians, including many qualified professionals, to emigrate in a "brain drain". The reform package introduced in 1997 restored positive economic growth, but led to rising social inequality. The political and economic system after 1989 virtually failed to improve both the living standards and create economic growth. According to a 2009 Pew Global Attitudes Project survey, 76% of Bulgarians said they were dissatisfied with the system of democracy, 63% thought that free markets did not make people better off and only 11% of Bulgarians agreed that ordinary people had benefited from the changes in 1989.[109] Furthermore, the average quality of life and economic performance actually remained lower than in the times of socialism well into the early 2000s (decade).[110]

Bulgaria became a member of NATO in 2004 and of the European Union in 2007. In 2010 it was ranked 32nd (between Greece and Lithuania) out of 181 countries in the Globalization Index.[111] The freedom of speech and of the press are respected by the government (as of 2015), but many media outlets are beholden to major advertisers and owners with political agendas.[112] Also see Human rights in Bulgaria. Polls carried out seven years after the country's accession to the EU found only 15% of Bulgarians felt they had personally benefited from the membership.[113]

See also

- Timeline of Bulgarian history

- Hominid dispersals in Europe

- Cradle of civilization

- Neolithic Revolution

- Neolithic Europe

- Thracians

- Moesi

- Getae

- List of ancient Daco-Thracian peoples and tribes

- Dacians

- Paeonia (kingdom)

- Scythians

- Classical Antiquity

- Timeline of Varna

- Philippopolis (Thrace)

- Celtic settlement of Southeast Europe

- List of archaeological sites by country

- History of Sofia

- Edict of Serdica

- Ancient Roman architecture

- Early centers of Christianity

- List of oldest known surviving buildings

- List of oldest church buildings

- Fresco

- Migration Period

- Gothic Bible

- Bulgarian Empire

- Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian culture

- Early Cyrillic alphabet

- Balkan–Danubian culture

- Bulgarian–Latin wars

- Tsarevets (fortress)

- Architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School

- Tarnovo Literary School

- Baba Vida

- Byzantine–Bulgarian wars

- National awakening of Bulgaria

- Bulgarian unification

- List of Bulgarian monarchs

- Medieval Bulgarian army

- Medieval Bulgarian navy

- Bulgarian lands across the Danube

- Bulgarian language

- Bulgarian dialects

- List of predecessors of sovereign states in Europe

- List of sovereign states by date of formation § Europe

- Timeline of sovereign states in Europe

- List of empires

- List of medieval great powers

- List of oldest continuously inhabited cities

- History of the Balkans

- History of the Mediterranean region

- History of Europe

References

- "Sirakov et al. (2010).- an ancient continuous human presence in the Balkans and the beginnings of human settlement in western Eurasia: A Lower Pleistocene example of the Lower Palaeolithic levels in Kozarnika cave (North-western Bulgaria) | Philippe Fernandez - Academia.edu". academia.edu. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7 pp 135–138, pp 343–345

- Xenophon (8 September 2005). The Expedition of Cyrus. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191605048. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Runciman, p. 26

- Bulgaria - Introduction, Library of Congress

- Sale, Kirkpatrick (2006). After Eden: The evolution of human domination. Duke University Press. p. 48. ISBN 0822339382. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- The Neolithic Dwellings Archived 2011-11-28 at the Wayback Machine at the Stara Zagora Neolithic Dwellings Museum website

- Slavchev, Vladimir (2004–2005). Monuments of the final phase of Cultures Hamangia and Savia on the territory of Bulgaria (PDF). pp. 9–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-18.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Chapman, John (2000). Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places, and Broken Objects. London: Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-415-15803-9.

- Squires, Nick (31 October 2012). "Archaeologists find Europe's most prehistoric town". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- Vaysov, I. (2002). Атлас по история на Стария свят. Sofia. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (in Bulgarian) - The Gumelnita Culture, Government of France. The Necropolis at Varna is an important site in understanding this culture.

- Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and gemstones: Timeless natural beauty of the mineral world. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600BC and 4,200BC).

- Mallory, J.P. (1997). Ezero Culture.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Hoddinott, p. 27.

- Casson, p. 3.

- Noorbergen, Rene (2004). Treasures of Lost Races. Teach Services Inc. p. 72. ISBN 1-57258-267-7.

- Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 1515. "From the 8th century BC the coast Thrace was colonised by Greeks."

- 2002 Oxford Atlas of World History p.42 (West portion of the Achaemenid Empire) Archived 29 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine and p.43 (East portion of the Achaemenid Empire).

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth,ISBN 0-19-860641-9,"page 1515,"The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- Timothy Howe, Jeanne Reames. Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza (original from the Indiana University) Regina Books, 2008 ISBN 978-1-930053-56-4 p 239

- "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Thracian Treasures from Bulgaria". 1981. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Dimitri Romanoff. The orders, medals, and history of the Kingdom of Bulgaria Balkan Heritage, 1982 ISBN 978-87-981267-0-6 p 9

- E.O. Blunsom. The Past And Future Of Law Xlibris Corporation, 10 apr. 2013 ISBN 978-1-4628-7516-0 p 101

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (7 July 2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444351637. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Robin Waterfield. "The Expedition of Cyrus" OUP Oxford, 2005. ISBN 0-19-160504-2 p 221

-

Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Frank William Walbank (1988). A History of Macedonia: 336-167 B.C. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-19-814815-9. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

Whereas Philip had exacted from the Thracians subjugated in 344 a tribute of one tenth of their produce payable to the Macedones ... , it seems that Alexander did not impose any tribute on the Triballi or on the down-river Thracians.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (2002). The Celts: A History. Cork: The Collins Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-85115-923-0. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

This, however, had little effect on the Celts, who within some years reached as far as Bulgaria. There, in 298 BC, a large body of them clashed with Cassander's army on the slopes of Mount Haemos. ... The power of the Thracians had been reduced by the Macedonians, and now much of the area fell into Celtic hands. Many placenames of that area in ancient times bear witness to the presence of Celtic strongholds ...

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic culture: A historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 156. ISBN 1-85109-440-7. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

Their influence in Thrace (roughly modern Bulgaria and European Turkey) is very modest, with only occasional samples of armour and jewellery, but they established a kingdom known as Tylis (alternatively Tyle) on the Thracian coast of the Black Sea.

- Haywood, John (2004). The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age. Pearson Education Limited. p. 28. ISBN 0-582-50578-X. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

A clearer example of interaction between Celts and Thacians is the famous Gundestrup cauldron, which was found in a Danish peat bog. This spectacular silver cauldron is decorated with images of Celtic gods and warriors but its workmanship is quite obviously Thracian, the product of a Thracian craftsman for a celtic patron ...

- Nikola Theodossiev, "Celtic Settlement in North-Western Thrace during the Late Fourth and Third Centuries BC".

- The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond, ISBN 0-521-22717-8, 1992, page 600: "In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long being supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin."

- "Temple to Isis and Osiris unearthed near the Bulgarian Black Sea". The Sofia Echo. 17 October 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2012.

- Thompson, E.A. (2009). The Visigoths in the Time of Ulfila. Ducksworth.

... Ulfila, the apostle of the Goths and the father of Germanic literature.

- "The Saint Athanasius Monastery of Chirpan, the oldest cloister in Europe" (in Bulgarian). Bulgarian National Radio. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Christianity and the Rhetoric of Empire: The Development of Christian Discourse, Averil Cameron, University of California Press, 1994, ISBN 0-520-08923-5, PP. 189–190.

- A history of the Greek language: from its origins to the present, Francisco Rodríguez Adrados, BRILL, 2005, ISBN 90-04-12835-2, p. 226.

- R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, 1997, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-56719-X

- Ivaylo Lozanov, Roman Thrace, pp. 75-90 in Julia Valeva, Emil Nankov, Denver Graninger as ed. (2020) A Companion to Ancient Thrace, Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 1119016185.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 780.

- Иван Микулчиќ, "Средновековни градови и тврдини во Македонија", Скопје, "Македонска цивилизација", 1996, стр. 29–33.

- Mikulčik, Ivan (1996). Srednovekovni gradovi i tvrdini vo Makedonija [Medieval cities and castles in Macedonia]. Македонска цивилизација [Macedonian civilization] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite. p. 391. ISBN 9989-649-08-1.

- L. Ivanov. Essential History of Bulgaria in Seven Pages. Sofia, 2007.

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press

- Boris Todorov, "The value of empire: tenth-century Bulgaria between Magyars, Pechenegs and Byzantium," Journal of Medieval History (2010) 36#4 pp 312–326

- "The First Bulgarian Empire". Encarta. Archived from the original on 2007-12-04. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- Bakalov, Istorija na Bǎlgarija, "Simeon I Veliki"

- "About Bulgaria" (PDF). U.S. Embassy Sofia, Bulgaria. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- Castellan, Georges (1999). Istorija na Balkanite XIV–XX vek (in Bulgarian). trans. Liljana Caneva. Plovdiv: Hermes. p. 37. ISBN 954-459-901-0.

- Fine 1991, p. 172

- Fine 1991, p. 176

- Kazhdan 1991, p. 301

- Reign of Simeon I, Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2011. Quote: Under Simeon's successors Bulgaria was beset by internal dissension provoked by the spread of Bogomilism (a dualist religious sect) and by assaults from Magyars, Pechenegs, the Rus, and Byzantines.

- Browning, Robert (1975). Byzantium and Bulgaria. Temple Smith. pp. 194–5. ISBN 0-85117-064-1.

- Leo Diaconus: Historia Archived 2011-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, Historical Resources on Kievan Rus. Retrieved 4 December 2011. Quote:Так в течение двух дней был завоеван и стал владением ромеев город Преслава. (in Russian)

- Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, full translation in Russian. Vostlit - Eastern Literature Resources. Retrieved 4 December 2011. Quote: В то время пока Владимир был юношей и правил на престоле своего отца, вышеупомянутый Самуил собрал большое войско и прибыл в далматинские окраины, в землю короля Владимира. (in Russian)

- Pavlov, Plamen (2005). "Заговорите на "магистър Пресиан Българина"". Бунтари и авантюристи в Средновековна България. LiterNet. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

И така, през пролетта на 1018 г. "партията на капитулацията" надделяла, а Василий II безпрепятствено влязъл в тогавашната българска столица Охрид.

(in Bulgarian) - "Bulgaria - history - geography". 23 August 2023.

- Zlatarski, vol. II, pp. 1–41

- Averil Cameron, The Byzantines, Blackwell Publishing (2006), p. 170

- "Войните на цар Калоян (1197–1207 г.) (in Bulgarian)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Ivanov, Lyubomir (2007). ESSENTIAL HISTORY OF BULGARIA IN SEVEN PAGES. Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

The capital Tarnovo became a political, economic, cultural and religious center seen as 'the Third Rome' in contrast to Constantinople's decline after the Byzantine heartland in Asia Minor was lost to the Turks during the late 11th century.

- The Golden Horde Archived 2011-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress Mongolia country study. Retrieved 4 December 2011. Quote:"The Mongols maintained sovereignty over eastern Russia from 1240 to 1480, and they controlled the upper Volga area, the territories of the former Volga Bulghar state, Siberia, the northern Caucasus, Bulgaria (for a time), the Crimea, and Khwarizm".

- Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries, Morrow QuillPaperback Edition, 1979

- D. Hupchick, The Balkans, 2002

- Bojidar Dimitrov: Bulgaria Illustrated History. BORIANA Publishing House 2002, ISBN 954-500-044-9

- Kemal H. Karpat, Social Change and Politics in Turkey: A Structural-Historical Analysis, BRILL, 1973, ISBN 90-04-03817-5, pp. 36–39

- Dennis P. Hupchick: The Balkans: from Constantinople to Communism, 2002

- San Stefano, Berlin, and Independence, Library of Congress Country Study. Retrieved 4 December 2011

- Blamires, Cyprian (2006). World Fascism: A historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 1-57607-941-4. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

The "Greater Bulgaria" re-established in March 1878 on the lines of the medieval Bulgarian empire after liberation from Turkish rule did not last long.

- Historical Setting, The Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 December 2011

- "Timeline: Bulgaria – A chronology of key events". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- K. Theodore Hoppen, The Mid-Victorian generation, 1846–1886 (1998) pp 625–26.

- L.S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (1958) pp 425-47.

- Duncan M. Perry, Stefan Stambolov and the emergence of modern Bulgaria, 1870-1895 (Duke University Press, 1993).

- John Bell, "The Genesis of Agrarianism in Bulgaria," Balkan Studies, (1975) 16#2 pp 73–92

- Nedyalka Videva, and Stilian Yotov, "European Moral Values and their Reception in Bulgarian Education," Studies in East European Thought, March 2001, Vol. 53 Issue 1/2, pp 119–128

- Pundeff, 1992 pp 65–70

- Dillon, Emile Joseph (February 1920) [1920]. "XV". The Inside Story of the Peace Conference. Harper. ISBN 978-3-8424-7594-6. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

The territorial changes which the Prussia of the Balkans was condemned to undergo are neither very considerable nor unjust.

- Pinon, Rene (1913). L'Europe et la Jeune Turquie: les aspects nouveaux de la question d'Orient (in French). Paris: Perrin et cie. ISBN 978-1-144-41381-9.

On a dit souvent de la Bulgarie qu'elle est la Prusse des Balkans

- Balabanov, A. (1983). И аз на тоя свят. Спомени от разни времена. pp. 72–361. (in Bulgarian)

- Pundeff, 1992 pp 70–72

- Charles Jelavich and Barbara Jelavich, The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920 (1977) pp 216–21, 289

- Richard C. Hall, "Bulgaria in the First World War," Historian, (Summer 2011) 73#2 pp 300–315

- Charles Jelavich and Barbara Jelavich, The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920 (1977) pp 289–90

- Gerard E. Silberstein, "The Serbian Campaign of 1915: Its Diplomatic Background," American Historical Review, October 1967, Vol. 73 Issue 1, pp 51–69 in JSTOR

- Tucker, Spencer C; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I. ABC-Clio. p. 273. ISBN 1-85109-420-2. OCLC 61247250.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Klein, Alexander (8 February 2008). "Aggregate and per capita GDP in Europe, 1870–2000: Continental, regional and national data with changing boundaries" (PDF). Department of Economics at the University of Warwick, Coventry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Raymond Detrez (2014). Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 346. ISBN 9781442241800.

- John D. Bell, Peasants in Power: Alexander Stamboliski and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, 1899–1923 (1977)

- "THE GERMAN CAMPAIGN IN THE BALKANS (SPRING 1941): PART I". history.army.mil. Retrieved 2022-01-20.