Taoism

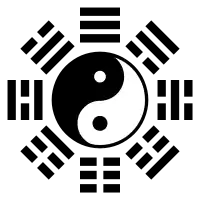

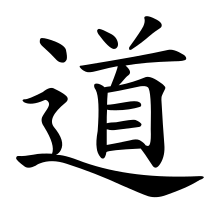

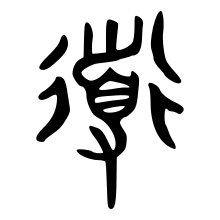

Taoism or Daoism[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈtaʊɪzəm/ ⓘ or /ˈdaʊɪzəm/ ⓘ) is a diverse tradition indigenous to China, variously characterized as both a philosophy and a religion. Taoism emphasizes living in harmony with what is known as the Tao—generally understood as being the impersonal, enigmatic process of transformation ultimately underlying reality.[3][4] The Tao is represented in Chinese by the character 道 (pinyin: dào; Wade–Giles: tao4), which has several related meanings; possible English translations for it include 'way', 'road', and 'technique'. Symbols such as the bagua and taijitu are often employed to illustrate various aspects of the Tao, which can never be sufficiently described with words and metaphors alone. Taoist thought has informed the development of various practices and rituals within the Taoist tradition and beyond, including forms of meditation, astrology, qigong, feng shui, and internal alchemy. A common goal of Taoist practice is self-cultivation resulting in a deeper appreciation of the Tao, and thus a more harmonious existence.

| Taoism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Chinese character for the Tao, often translated as 'way', 'path', 'technique', or 'doctrine' | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Dàojiào[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Religion of the Way" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Đạo giáo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 도교 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 道敎 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 道教 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | どうきょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

Different schools present different formulations of Taoist ethics, but there is generally an emphasis on virtues such as effortless action, naturalness or spontaneity, simplicity, and the three treasures of compassion, frugality, and humility. Due to the terse quality of Classical Chinese as well as the abstract nature of the ideas themselves, many of these concepts defy simple definitions: Taoist terms have been translated into English in numerous different ways, occasionally resulting in divergent interpretations of Taoist ideas.

The core of Taoist thought crystallized during the early Warring States period circa the 4th and 5th centuries. The two works widely regarded as the principal expressions of Taoist philosophy, the epigrammatic Tao Te Ching and the anecdotal Zhuangzi, were both partly composed during this time. They form the foundation of a large corpus of Taoist writings accrued over the following centuries; in the 5th century CE much of it began to be assembled by Taoist monks into the Daozang canon. Early Taoism drew upon a diverse set of influences, including the Shang and Zhou state religions, Naturalism, Mohism, Confucianism, the Legalist theories of figures like Shen Buhai and Han Fei, as well as the Book of Changes and Spring and Autumn Annals.[5][6][7] Later, when Buddhism was introduced to China, the two systems began deeply influencing one another, with long-running discourses shared between Taoists and Buddhists; the distinct Zen tradition within Mahayana Buddhism that emerged during the Tang dynasty keenly incorporates many ideas from Taoism.

Though Taoism often lacks the motivation for strong ecclesiastical hierarchies, Taoist organizations with diverse agendas and levels of organization have existed throughout Chinese history—indeed, Taoist philosophy has often served as a foundation for theories of politics and warfare. In one famous example, Taoist secret societies precipitated the Yellow Turban Rebellion during the late Han dynasty, with the intent of replacing the Han with what has been characterized as a Taoist theocracy. The status of daoshi, or 'Taoist master', is traditionally only attributed to clergy in Taoist organizations. Daoshi often take care to note distinctions between their traditions and others throughout Chinese folk religion, as well as those between their organizations and other vernacular ritual orders often associated with Taoism by the public. Many denominations of Taoism recognize various deities, often ones shared with other Chinese religions, with adherents worshiping them as powerful, superhuman figures exemplifying Taoist virtues.

The highly syncretic nature of Taoist tradition presents particular difficulties when attempting to characterize its practice and identify adherents: debatably moreso than with other traditions, attempting to define what makes one a ‘Taoist' is a problematic exercise. Taoist thought has been deeply rooted in Sinosphere society for millennia, and a given individual's apparent adherence may or may not correspond to their self-identification as an adherent per se. Today, Taoism is one of five religious doctrines officially recognized by the Chinese government, also having official status in Hong Kong and Macau.[8] It is also considered a major religion within Taiwan,[9] and it has significant populations of adherents throughout the Sinosphere and Southeast Asia, particularly in Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore. Taoism has also taken on diverse forms in the West, including those hewing to historical practice, as well as highly synthesized practices variously characterized as new religious movements and often associated with the New Age subculture.

Terminology

Spelling and pronunciation

From the advent of Western attention towards Taoism until the latter half of the 20th century, Wade–Giles was the predominant system for writing Chinese words with the Latin alphabet, a process known as romanization. The Wade–Giles romanization of the Chinese character 道 is tao. In recent decades, the newer Hanyu Pinyin system for romanizing Standard Chinese has largely replaced Wade–Giles in many contexts, including when teaching the language, as well as when borrowing terms not already strongly associated with a previous spelling. Due to this history, both "Taoism" and "Daoism" are now common spellings.

The Standard Chinese pronunciation of the word is /tâʊ/, which uses an unvoiced, unaspirated consonant, like the ⟨t⟩ in English, though this precise phone does not occur at the onset of words according to English phonotactics. Native English speakers are inclined to pronounce "Taoism" and "Daoism" slightly differently, though generally not with the Standard Chinese consonant using either, hence the potential discrepancy.[10]

Classification

The word Taoism is used to translate two related but distinct Chinese terms.[11]

- Firstly, a term encompassing a family of organized religious movements that share concepts and terminology from Taoist philosophy—what can be specifically translated as 'the teachings of the Tao', (道教; dàojiào), often interpreted as the Taoist "religion proper", or the "mystical" or "liturgical" aspects of Taoism.[12] is [13] The Celestial Masters school is a well-known early example of this sense.

- The other, referring to the philosophical doctrines largely based on core Taoist texts themselves—a term that can be translated as 'the philosophical school of the Tao' or 'Taology' (道家; dàojiā; 'school of the Tao', or sometimes 道學; dàoxué; 'study of the Tao'). This was considered one of the Hundred Schools of Thought during the Warring States period. The earliest recorded use of the word 'Tao' to reference such a philosophical school is found in the works of Han-era historians:[14][15] such as the Commentary of Zhuo (左传; Zuǒzhuàn) by Zuo Qiuming, and in the Records of the Grand Historian. This particular usage precedes the emergence of the Celestial Masters and associated later religions. It is unlikely that Zhuang Zhou, author of the Zhuangzi, was familiar with the text of the Tao Te Ching,[15][16] and Zhuangzi himself may have died before the term was in use.[16]

The distinction between Taoist philosophy and Taoist religion is an ancient, deeply-rooted one. The earliest references to 'the Tao' per se are largely devoid of liturgical or explicitly supernatural character, used in contexts either of abstract metaphysics or of the ordinary conditions required for human flourishing. This distinction is still understood in everyday contexts among Chinese people, and has been echoed by modern scholars of Chinese history and philosophy such as Feng Youlan and Wing-tsit Chan. Use of the term daojia dates to the Western Han c. 100 BCE, referring to the purported authors of the emerging Taoist canon, such as Lao Dan and Zhuang Zhou.[17][18] Neither the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi themselves, nor the early secondary sources written about them, put forward any particular supernatural ontology. Nonetheless, that religious Taoism emerged from a synthesis of folk religion with philosophical Taoist precepts is clear. The earlier, naturalistic was employed by pre-Han and Han thinkers, and continued to be used well into the Song, including among those who explicitly rejected cults, both private and state-sanctioned, that were often either labeled or self-identified as Taoist.

However, this distinction has been challenged or rejected by some scholars of religion, often those from a Western or Japanese background, who often use distinct interpretive models and techniques.[19] This point of view characterizes the religious and philosophical characteristics of the Taoist tradition as being inseparable. Sinologists such as Isabelle Robinet and Livia Kohn state that "Taoism has never been a unified religion, and has constantly consisted of a combination of teachings based on a variety of original revelations." The distinction is fraught with hermeneutic difficulties when attempting to categorize different schools, sects, and movements.[20] Russell Kirkland writes that "most scholars who have seriously studied Taoism, both in Asia and in the West" have abandoned this "simplistic dichotomy".[21] Louis Komjathy writes that this is an untenable misconception because "the association of daojia with "thought" (sixiang) and of daojiao with "religion" (zongjiao) is a modern Chinese construction largely rooted in earlier Chinese literati, European colonialist, and Protestant missionary interpretations." Contemperaneous Neo-Confucianists, for example, often self-identify as Taoist without partaking in any rituals.[22]

In contrast, Komjathy characterizes Taoism as "a unified religious tradition characterized by complexity and diversity.", arguing that historically, none of these terms were understood according to a bifurcated 'philosophy' versus 'religion' model. Daojia was a taxonomical category for Taoist texts, that was eventually applied to Taoist movements and priests in the early medieval period. [23] Meanwhile, daojiao was originally used to specifically distinguish Taoist tradition from Buddhism. Thus, daojiao included daojia.[23] Komjathy notes that the earliest Taoist texts also "reveal a religious community composed of master-disciple lineages", and therefore, that "Taoism was a religious tradition from the beginning."[23] Philosopher Chung-ying Cheng likewise views Taoism as a religion embedded into Chinese history and tradition, while also assuming many different "forms of philosophy and practical wisdom".[24] Chung-ying Cheng also noted that the Taoist view of 'heaven' mainly from "observation and meditation, [though] the teaching of [the Tao] can also include the way of heaven independently of human nature".[24] Taoism is generally not understood as a variant of Chinese folk religion per se: while the two umbrella terms have considerable cultural overlap, core themes of both also diverge considerably from one another.[25]

Adherents

Traditionally, the Chinese language does not have terms defining lay people adhering to the doctrines or the practices of Taoism, who fall instead within the field of folk religion. Taoist, in Western sinology, is traditionally used to translate daoshi/taoshih (道士, "master of the Dao"), thus strictly defining the priests of Taoism, ordained clergymen of a Taoist institution who "represent Taoist culture on a professional basis", are experts of Taoist liturgy, and therefore can employ this knowledge and ritual skill for the benefit of a community.[26]

This role of Taoist priests reflects the definition of Taoism as a "liturgical framework for the development of local cults", in other words a scheme or structure for Chinese religion, proposed first by the scholar and Taoist initiate Kristofer Schipper in The Taoist Body (1986).[27] Taoshi are comparable to the non-Taoist ritual masters(法師) of vernacular traditions (the so-called Faism) within Chinese religion.[27]

The term dàojiàotú (道敎徒; 'follower of Dao'), with the meaning of "Taoist" as "lay member or believer of Taoism", is a modern invention that goes back to the introduction of the Western category of "organized religion" in China in the 20th century, but it has no significance for most of Chinese society in which Taoism continues to be an "order" of the larger body of Chinese religion.

History

Classical Taoism and its sources

Scholars like Harold Roth argue that early Taoism was a series of "inner-cultivation lineages" of master-disciple communities. According to Roth, these practitioners emphasized a contentless and nonconceptual apophatic meditation as a way of achieving union with the Dao.[28] According to Louis Komjathy, their worldview "emphasized the Dao as sacred, and the universe and each individual being as a manifestation of the Dao."[29] These communities were also closely related to and intermixed with the fangshi (method master) communities.[30]

Other scholars, like Russell Kirkland, argue that before the Han dynasty, there were no real "Taoists" or "Taoism". Instead, there were various sets of behaviors, practices, and interpretative frameworks (like the ideas of the Yijing, yin-yang thought, as well as Mohist, "Legalist", and "Confucian" ideas), which were eventually synthesized in the medieval era into the first forms of "Taoism".[31]

Some of the main early Taoist sources include: the Neiye, the Zhuangzi, and the Tao Te Ching.[32] The Tao Te Ching, which is attributed to Lao Tzu or Laozi (the "Old Master"), is dated by scholars to sometime between the 4th and 6th century BCE.[33][34]

According to tradition, many Taoists believe that Lao Tzu founded Taoism.[35] Laozi's historicity is disputed, with many scholars seeing him as a legendary founding figure.[36][37]

While Taoism is often regarded in the West as arising from Laozi, many Chinese Taoists claim that the Yellow Emperor formulated many of their precepts,[38] including the quest for "long life".[39] Traditionally, the Yellow Emperor's founding of Taoism was said to have been because he "dreamed of an ideal kingdom whose tranquil inhabitants lived in harmonious accord with the natural law and possessed virtues remarkably like those espoused by early Taoism. On waking from his dream, Huangdi sought to" bring about "these virtues in his own kingdom, to ensure order and prosperity among the inhabitants".[40]

Early Taoism drew on the ideas found in the religion of the Shang dynasty and the Zhou dynasty, such as their use of divination, ancestor worship, and the idea of Heaven (Tian) and its relationship to humanity.[6] According to modern scholars of Taoism, such as Kirkland and Livia Kohn, Taoist philosophy also developed by drawing on numerous schools of thought from the Warring States Period (4th to 3rd centuries BCE), including Mohism, Confucianism, Legalist theorists (like Shen Buhai and Han Fei, which speak of Wu wei), the School of Naturalists (from which Taoism draws its main cosmological ideas, yin and yang and the five phases), and the Chinese classics, especially the I Ching and the Lüshi Chunqiu.[5][6][7]

Meanwhile, Isabelle Robinet identifies four components in the emergence of Taoism: the teachings found in the Daodejing and Zhuangzi, techniques for achieving ecstasy, practices for achieving longevity and becoming an immortal (xian), and practices for exorcism.[36] Robinet states that some elements of Taoism may be traced to prehistoric folk religions in China.[41] In particular, many Taoist practices drew from the Warring States era phenomena of the wu (Chinese shamans) and the fangshi ("method masters", which probably derived from the "archivist-soothsayers of antiquity").[42]

Both terms were used to designate individuals dedicated to "...magic, medicine, divination,... methods of longevity and to ecstatic wanderings" as well as exorcism.[42] The fangshi were philosophically close to the School of Naturalists and relied greatly on astrological and calendrical speculations in their divinatory activities.[43] Female shamans played an important role in the early Taoist tradition, which was particularly strong in the southern state of Chu. Early Taoist movements developed their own tradition in contrast to shamanism while also absorbing shamanic elements.[44]

During the early period, some Daoists lived as hermits or recluses who did not participate in political life, while others sought to establish a harmonious society based on Daoist principles.[29] Zhuang Zhou (c. 370–290 BCE) was the most influential of the Daoist hermits. Some scholars holds that since he lived in the south, he may have been influenced by Chinese shamanism.[45] Zhuang Zhou and his followers insisted they were the heirs of ancient traditions and the ways of life of by-then legendary kingdoms.[46] Pre-Daoist philosophers and mystics whose activities may have influenced Daoism included shamans, naturalists skilled in understanding the properties of plants and geology, diviners, early environmentalists, tribal chieftains, court scribes and commoner members of governments, members of the nobility in Chinese states, and the descendants of refugee communities.[47]

Significant movements in early Daoism disregarded the existence of gods, and many who believed in gods thought they were subject to the natural law of the Tao, in a similar nature to all other life.[48][49] Roughly contemporaneously to the Daodejing, some believed the Dao was a force that was the "basis of all existence" and more powerful than the gods, while being a god-like being that was an ancestor and a mother goddess.[50]

Early Taoists studied the natural world in attempts to find what they thought were supernatural laws that governed existence.[34] Taoists created scientific principles that were the first of their kind in China, and the belief system has been known to merge scientific, philosophical, and religious conceits from close to its beginning.[34]

Early organized Taoism

By the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the various sources of Taoism had coalesced into a coherent tradition of ritualists in the state of Shu (modern Sichuan).[45] One of the earliest forms of Taoism was the Han era (2nd century BCE) Huang–Lao movement, which was an influential school of thought at this time.[51] The Huainanzi and the Taipingjing are important sources from this period.[52] An unorganized form of Taoism was popular in the Han dynasty that syncretized many preexisting forms in multiple ways for different groups existed during a rough span of time throughout the 2nd century BCE.[53] Also during the Han, the earliest extant commentaries on the Daodejing were written: the Heshang Gong commentary and the Xiang'er commentary.[54][55]

The first organized form of Taoism was the Way of the Celestial Masters (Tianshi Dao), which developed from the Five Pecks of Rice movement at the end of the 2nd century CE. The latter had been founded by Zhang Taoling, who was said to have had a vision of Laozi in 142 CE and claimed that the world was coming to an end.[56][57] Zhang sought to teach people to repent and prepare for the coming cataclysm, after which they would become the seeds of a new era of great peace (taiping). It was a mass movement in which men and women could act as libationers and tend to the commoners.[58] A related movement arose in Shandong called the "Way of Great Peace", seeking to create a new world by replacing the Han dynasty. This movement led to the Yellow Turban Rebellion, and after years of bloody war, they were crushed.[57]

The Celestial Masters movement survived this period and did not take part in attempting to replace the Han. As such, they grew and became an influential religion during the Three Kingdoms period, focusing on ritual confession and petition, as well as developing a well-organized religious structure.[59] The Celestial Masters school was officially recognized by the warlord Cao Cao in 215 CE, legitimizing Cao Cao's rise to power in return.[60] Laozi received imperial recognition as a divinity in the mid-2nd century BCE.[61]

Another important early Taoist movement was Taiqing (Great Clarity), which was a tradition of external alchemy (weidan) that sought immortality through the concoction of elixirs, often using toxic elements like cinnabar, lead, mercury, and realgar, as well as ritual and purificatory practices.[62]

After this point, Taoism did not have nearly as significant an effect on the passing of law as the syncretic Confucian-Legalist tradition.

Three Kingdoms and Six Dynasties eras

The Three Kingdoms Period saw the rise of the Xuanxue (Mysterious Learning or Deep Wisdom) tradition, which focused on philosophical inquiry and integrated Confucian teachings with Taoist thought. The movement included scholars like Wang Bi (226–249), He Yan (d. 249), Xiang Xiu (223?–300), Guo Xiang (d. 312), and Pei Wei (267–300).[63] Another later influential figure was the 4th century alchemist Ge Hong, who wrote a key Taoist work on inner cultivation, the Baopuzi (Master Embracing Simplicity).[64]

The Six Dynasties (316–589) era saw the rise of two new Taoist traditions, Shangqing (Supreme Clarity) and Lingbao (Numinous Treasure). Shangqing was based on a series of revelations by gods and spirits to a certain Yang Xi between 364 and 370. As Livia Kohn writes, these revelations included detailed descriptions of the heavens as well as "specific methods of shamanic travels or ecstatic excursions, visualizations, and alchemical concoctions."[65] The Shangqing revelations also introduced many new Taoist scriptures.[66]

Similarly, between 397 and 402, Ge Chaofu compiled a series of scriptures that later served as the foundation of the Lingbao school, which was most influential during the later Song dynasty (960–1279) and focused on scriptural recitation and the use of talismans for harmony and longevity.[67][68] The Lingbao school practiced purification rituals called purgations (zhai) in which talismans were empowered. Lingbao also adopted Mahayana Buddhist elements. According to Kohn, they "integrated aspects of Buddhist cosmology, worldview, scriptures, and practices, and created a vast new collection of Taoist texts in close imitation of Buddhist sutras."[69] Louis Komjathy also notes that they adopted the Mahayana Buddhist universalism in its promotion of "universal salvation" (pudu).[70]

During this period, Louguan, the first Taoist monastic institution (influenced by Buddhist monasticism) was established in the Zhongnan mountains by a local Taoist master named Yin Tong. This tradition was called the Northern Celestial masters, and their main scripture was the Xisheng jing (Scripture of Western Ascension).[71]

During the sixth century, Taoists attempted to unify the various traditions into one integrated Taoism that could compete with Buddhism and Confucianism. To do this they adopted the schema known as the "three caverns", first developed by the scholar Lu Xiujing (406–477) based on the "three vehicles" of Buddhism. The three caverns were: Perfection (Dongzhen), associated with the Three Sovereigns; Mystery (Dongxuan), associated with Lingbao; and Spirit (Dongshen), associated with the Supreme Clarity tradition.[72] Lu Xiujing also used this schema to arrange the Taoist scriptures and Taoist deities. Lu Xiujing worked to compile the first edition of the Daozang (the Taoist Canon), which was published at the behest of the Chinese emperor. Thus, according to Russell Kirkland, "in several important senses, it was really Lu Hsiu-ching who founded Taoism, for it was he who first gained community acceptance for a common canon of texts, which established the boundaries, and contents, of 'the teachings of the Tao' (Tao-chiao). Lu also reconfigured the ritual activities of the tradition, and formulated a new set of liturgies, which continue to influence Taoist practice to the present day."[73]

This period also saw the development of the Three Pure Ones, which merged the high deities from different Taoist traditions into a common trinity that has remained influential until today.[72]

Later Imperial Dynasties

The new Integrated Taoism, now with a united Taoist identity, gained official status in China during the Tang dynasty. This tradition was termed HP: Daojiao/WP: Taochiao (the teaching of the Tao).[74] The Tang was the height of Taoist influence, during which Taoism, led by the Patriarch of Supreme Clarity, was the dominant religion in China.[75][76][74] According to Russell Kirkland, this new Taoist synthesis had its main foundation in the Lingbao school's teachings, which was appealing to all classes of society and drew on Mahayana Buddhism.[77]

Perhaps the most important figure of the Tang was the court Taoist and writer Du Guangting (850–933). Du wrote numerous works about Taoist rituals, history, myth, and biography. He also reorganized and edited the Taotsang after a period of war and loss.[78]

During the Tang, several emperors became patrons of Taoism, inviting priests to court to conduct rituals and enhance the prestige of the sovereign.[79] The Gaozong Emperor even decreed that the Daodejing was to be a topic in the imperial examinations.[80] During the reign of the 7th century Emperor Taizong, the Five Dragons Temple (the first temple at the Wudang Mountains) was constructed.[81] Wudang would eventually become a major center for Taoism and a home for Taoist martial arts (Wudang quan).

Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–755) was also a devoted Taoist who wrote various Taoist works, and according to Livia Kohn, "had frequent meetings with senior masters, ritual specialists, Taoist poets, and official patriarchs, such as Sima Chengzhen."[82] He reorganized imperial rituals based on Taoist forms, sponsored Taoist shrines and monasteries, and introduced a separate examination system based on Taoism.[82] Another important Taoist figure of the Tang dynasty was Lu Dongbin, who is considered the founder of the jindan meditation tradition and an influential figure in the development of neidan (internal alchemy) practice.

Likewise, several Song dynasty emperors, most notably Huizong, were active in promoting Taoism, collecting Taoist texts, and publishing updated editions of the Daozang.[83] The Song era saw new scriptures and new movements of ritualists and Taoist rites, the most popular of which were the Thunder Rites (leifa). The Thunder rites were protection and exorcism rites that evoked the celestial department of thunder, and they became central to the new Heavenly Heart (Tianxin) tradition as well as for the Youthful Incipience (Tongchu) school.[84]

.jpg.webp)

In the 12th century, the Quanzhen (Complete Perfection) School was founded in Shandong by the sage Wang Chongyang (1113–1170) to compete with religious Taoist traditions that worshipped "ghosts and gods" and largely displaced them.[85] The school focused on inner transformation,[85] mystical experience,[85] monasticism, and asceticism.[86][87] Quanzhen flourished during the 13th and 14th centuries and during the Yuan dynasty. The Quanzhen school was syncretic, combining elements from Buddhism and Confucianism with Taoist tradition. According to Wang Chongyang, the "three teachings" (Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism), "when investigated, prove to be but one school".[88] Quanzhen became the largest and most important Taoist school in China when master Qiu Chuji met with Genghis Khan who ended up making him the leader of all Chinese religions as well as exempting Quanzhen institutions from taxation.[89][90] Another important Quanzhen figure was Zhang Boduan, author of the Wuzhen pian, a classic of internal alchemy, and the founder of the southern branch of Quanzhen.

During the Song era, the Zhengyi tradition properly developed in Southern China among Taoists of the Chang clan.[91] This liturgically focused tradition would continue to be supported by later emperors and survives to this day.[92]

Under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), aspects of Confucianism, Taoism, and East Asian Buddhism were consciously synthesized in the Neo-Confucian school, which eventually became Imperial orthodoxy for state bureaucratic purposes.[93] Taoist ideas also influenced Neo-Confucian thinkers like Wang Yangming and Zhan Ruoshui.[94] During the Ming, the legends of the Eight Immortals (the most important of which is Lü Dongbin) rose to prominence, being part of local plays and folk culture.[95] Ming emperors like the Hongwu Emperor continued to invite Taoists to court and hold Taoist rituals that were believed to enhance the power of the throne. The most important of these were connected with the Taoist deity Xuanwu ("Perfect Warrior"), which was the main dynastic protector deity of the Ming.[79]

The Ming era saw the rise of the Jingming ("Pure Illumination") school to prominence, which merged Taoism with Buddhist and Confucian teachings and focused on "purity, clarity, loyalty and filial piety".[96] [97] The school derided internal and external alchemy, fasting (bigu), and breathwork. Instead, the school focused on using mental cultivation to return to the mind's original purity and clarity (which could become obscured by desires and emotions).[96] Key figures of this school include Xu Xun, Liu Yu, Huang Yuanji, Xu Yi, and Liu Yuanran. Some of these figures taught at the imperial capital and were awarded titles.[96] Their emphasis on practical ethics and self-cultivation in everyday life (rather than ritual or monasticism) made it very popular among the literati class.[98]

The Qing dynasty (1644–1912) mainly promoted Buddhism as well as Neo-Confucianism.[98] Thus, during this period, the status and influence of Taoism declined. During the 18th century, the Qing imperial library excluded virtually all Taoist books.[99]

The Qing era also saw the birth of the Longmen ("Dragon Gate" 龍門) school of Wang Kunyang (1552–1641), a branch of Quanzhen from southern China that became established at the White Cloud Temple.[100][101] Longmen authors like Liu Yiming (1734–1821) and Min Yide (1758–1836) worked to promote and preserve Taoist inner alchemy practices through books like The Secret of the Golden Flower.[102] The Longmen school synthesized the Quanzhen and neidan teachings with the Chan Buddhist and Neo-Confucian elements that the Jingming tradition had developed, making it widely appealing to the literati class.[103]

Early modern Taoism

.jpg.webp)

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Taoism suffered much destruction as a result of religious persecution and numerous wars and conflicts that beset China in the so called century of humiliation. This period of persecution was caused by numerous factors including Confucian prejudices, anti-traditional Chinese modernist ideologies, European and Japanese colonialism, and Christian missionization.[104] By the 20th century, only one complete copy of the Tao Tsang survived intact, stored at the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing.[105] A key Taoist figure during this period was Chen Yingning (1880–1969). He was a key member of the early Chinese Taoist Association and wrote numerous books promoting Taoist practice [106]

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), many Taoist priests were laicized and sent to work camps, and many Taoist sites and temples were destroyed or converted to secular use.[107][108] This period saw an exodus of Taoists out of China. They immigrated to Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and to Europe and North America. Thus, the communist repression had the consequence of making Taoism a world religion by disseminating Taoists throughout the world.[109]

In the 1910s, Taoist doctrine about immortals and waiting until after death to live in "the dwelling of the immortals" was one of the faith's most popular and influential beliefs.[110]

The 20th century was also a creative period for Taoism despite its many setbacks. The Taoist influenced practice of Tai Chi developed during this time, led by figures like Yang Chengfu and Sun Lutang.[111] Early proponents of Tai Chi Quan, like Sun Lutang, claimed that Tai Chi was a Taoist internal practice created by the Taoist immortal Zhang Sanfeng (though modern scholars note that this claim lacks credible historical evidence).[112]

Late modern Taoism

Taoism began to recover during the Reform and Opening up period (beginning in 1979) after which it experienced increased religious freedom in mainland China.[113] This led to the restoration of many temples and communities, the publishing of Taoist literature and the preservation of Taoist material culture.[114] Several Chinese intellectuals, like Hu Fuchen (Chinese Academy of Social Studies) and Liu Xiaogan (Chinese University of Hong Kong) have worked to developed a "New Daojia" (xin daojia), which parallels the rise of New Confucianism.[115]

During the 1980s and 1990s, China experienced the so called Qigong fever, which saw a surge in the popularity of Qigong practice throughout China. During this period many new Taoist and Taoist influenced religions sprung up, the most popular being those associated with Qigong, such as Zangmigong (Tantric Qigong influenced by Tibetan Buddhism), Zhonggong (Central Qigong), and Falungong (which came to be outlawed and repressed by the Chinese Communist Party [CCP]).[106]

Today, Taoism is one of five official recognized religions in the People's Republic of China. In mainland China, the government regulates its activities through the Chinese Taoist Association.[116] Regarding the status of Taoism in mainland China, Livia Kohn writes:

Taoist institutions are state-owned, monastics are paid by the government, several bureaus compete for revenues and administrative power, and training centers require courses in Marxism as preparation for full ordination. Still, temple compounds are growing on the five sacred mountains, on Taoist mountains, and in all major cities.[117]

The White Cloud Temple at Beijing remains the most important center for the training of Taoist monastics on the mainland, while the five sacred mountains of China also contain influential Taoist centers. Other key sites include: Wudangshan, Mount Longhu, Mount Qiyun, Mount Qingcheng, Mount Tai, Zhongnan mountains, Mount Mao, and Mount Lao.[118] Meanwhile, Taoism is also practiced much more freely in Taiwan and Hong Kong, where it is a major religion and retains unique features and movements that differ from mainland Taoism.[119] Taoism is also practiced throughout the wider East Asian cultural sphere.[120]

Outside of China, many traditionally Taoist practices have spread, especially through Chinese emigration as well as conversion by non-Chinese.[120] Taoist influenced practices, like Tai chi and qigong, are also popular around the world.[121] As such, Taoism is now a diverse "world religion" with a global distribution.[120]

During the late 20th century, Taoism began to spread to the Western world, leading to various forms of Taoist communities in the West, with Taoist publications, websites, meditation and Tai chi centers, and translations of Taoist texts by western scholars as well as non-specialists.[122] Taoist classics like the Daodejing have also became popular in the New Age movement and in "popular Western Taoism", a kind of popularized hybrid spirituality.[123] According to Louis Komjathy, this "popular Western Taoism" is associated with popular translations and interpretations of the Daodejing and the work of popular figures like James Legge, Alan Watts, John Blofeld, Gia-fu Feng, and Bruce Lee.[124] This popular spirituality also draws on Chinese martial arts (which are often unrelated to Taoism proper), American Transcendentalism, 1960s counterculture, New Age spirituality, the perennial philosophy, and alternative medicine.[125]

On the other hand, traditionally minded Taoists in the West are often either ethnically Chinese or generally assume some level of sinification, especially the adoption of Chinese language and culture. This is because, for most traditional Taoists, the religion is not seen as separate from Chinese ethnicity and culture. As such, most Western convert Taoist groups are led either by Chinese teachers or by teachers who studied with Chinese teachers.[126] Some prominent Western Taoist associations include: Associacion de Taoism de España, Association Francaise Daoiste, British Daoist Association, Daoist Foundation (San Diego, California), American Taoist and Buddhist Association (New York), Ching Chung Taoist Association (San Francisco), Universal Society of the Integral Way (Ni Hua-Ching), and Sociedade Taoista do Brasil.[127]

Particularly popular in the West are groups that focus on internal martial arts like Taijiquan, as well as qigong and meditation. A smaller set of groups also focus around internal alchemy, such as Mantak Chia's Healing Dao.[128] While traditional Daoism initially arrived in the West through Chinese immigrants, more recently, Western run Daoist temples have also appeared, such as the Taoist Sanctuary in San Diego and the Dayuan Circle in San Francisco. Kohn notes that all of these centers "combine traditional ritual services with Daodejing and Yijing philosophy as well as with various health practices, such as breathing, diet, meditation, qigong, and soft martial arts."[129]

Teachings

Tao

Tao (or Dao) can mean way, road, channel, path, doctrine, or line.[130] Livia Kohn describes the Dao as "the underlying cosmic power which creates the universe, supports culture and the state, saves the good and punishes the wicked. Literally 'the way', Dao refers to the way things develop naturally, the way nature moves along and living beings grow and decline in accordance with cosmic laws."[131] The Dao is ultimately indescribable and transcends all analysis and definition. Thus, the Tao Te Ching begins with: "The Dao that can be told is not eternal Dao."[131] Likewise, Louis Komjathy writes that the Dao has been described by Taoists as "dark" (xuan), "indistinct" (hu), "obscure" (huang), and "silent" (mo).[132]

According to Komjathy, the Dao has four primary characteristics: "(1) Source of all existence; (2) Unnamable mystery; (3) All-pervading sacred presence; and (4) Universe as cosmological process."[133] As such, Taoist thought can be seen as monistic (the Dao is one reality), panenhenic (seeing nature as sacred), and panentheistic (the Dao is both the sacred world and what is beyond it, immanent and transcendent).[134] Similarly, Wing-Tsit Chan describes the Dao as an "ontological ground" and as "the One, which is natural, spontaneous, eternal, nameless, and indescribable. It is at once the beginning of all things and the way in which all things pursue their course."[135][136] The Dao is thus an "organic order", which is not a willful or self-conscious creator, but an infinite and boundless natural pattern.[131]

Furthermore, the Dao is something that individuals can find immanent in themselves, as well as in natural and social patterns.[137][131] Thus, the Dao is also the "innate nature" (xing) of all people, a nature which is seen by Taoists as being ultimately good.[138] In a naturalistic sense, the Dao as visible pattern, "the Dao that can be told", that is, the rhythmic processes and patterns of the natural world that can be observed and described.[131] Thus, Kohn writes that Dao can be explained as twofold: the transcendent, ineffable, mysterious Dao and the natural, visible, and tangible Dao.[131]

Throughout Taoist history, Taoists have developed different metaphysical views regarding the Dao. For example, while the Xuanxue thinker Wang Bi described Dao as wú (nothingness, negativity, not-being), Guo Xiang rejected wú as the source and held that instead the true source was spontaneous "self-production" (zìshēng 自生) and "self-transformation" (zìhuà 自化).[139] Another school, the Chóngxuán (Twofold Mystery), developed a metaphysics influenced by Buddhist Madhyamaka philosophy.[140]

De

The active expression of Dao is called De (德; dé; also spelled,Te or Teh; often translated with virtue or power),[141] in a sense that De results from an individual living and cultivating the Tao.[142] The term De can be used to refer to ethical virtue in the conventional Confucian sense, as well as to a higher spontaneous kind of sagely virtue or power that comes from following the Dao and practicing wu-wei. Thus, it is a natural expression of the Dao's power and not anything like conventional morality.[143] Louis Komjathy describes De as the manifestation of one's connection to the Dao, which is a beneficial influence of one's cosmological attunement.[144]

Ziran

Ziran (自然; zìrán; tzu-jan; lit. "self-so", "self-organization"[145]) is regarded as a central concept and value in Taoism and as a way of flowing with the Dao.[146][147] It describes the "primordial state" of all things[148] as well as a basic character of the Dao,[149] and is usually associated with spontaneity and creativity.[150] According to Kohn, in the Zhuangzi, ziran refers to the fact that "there is thus no ultimate cause to make things what they are. The universe exists by itself and of itself; it is existence just as it is. Nothing can be added or substracted from it; it is entirely sufficient upon itself."[151]

To attain naturalness, one has to identify with the Dao and flow with its natural rhythms as expressed in oneself.[149][152] This involves freeing oneself from selfishness and desire, and appreciating simplicity.[146] It also involves understanding one's nature and living in accordance with it, without trying to be something one is not or overthinking one's experience.[153] One way of cultivating ziran found in the Zhuangzi is to practice the "fasting of the mind", a kind of Taoist meditation in which one empties the mind. It is held that this can also activate qi (vital energy).[154] In some passages found in the Zhuangzi and in the Tao Te Ching, naturalness is also associated with rejection of the state (anarchism) and a desire to return to simpler pre-technological times (primitivism).[155]

An often cited metaphor for naturalness is pu (樸; pǔ, pú; p'u; lit. "uncut wood"), the "uncarved log", which represents the "original nature... prior to the imprint of culture" of an individual.[156] It is usually referred to as a state one may return to.[157]

Wu-wei

The polysemous term wu-wei or wuwei (無爲; wúwéi) constitutes the leading ethical concept in Taoism.[158] Wei refers to any intentional or deliberated action, while wu carries the meaning of "there is no ..." or "lacking, without". Common translations are nonaction, effortless action, action without intent, noninterference and nonintervention.[159][158] The meaning is sometimes emphasized by using the paradoxical expression "wei wu wei": action without action.[160] Kohn writes that wuwei refers to "letting go of egoistic concerns" and "to abstain from forceful and interfering measures that cause tensions and disruption in favor of gentleness, adaptation, and ease."[147]

In ancient Taoist texts, wu-wei is associated with water through its yielding nature and the effortless way it flows around obstacles.[161] Taoist philosophy, in accordance with the I Ching, proposes that the universe works harmoniously according to its own ways. When someone exerts their will against the world in a manner that is out of rhythm with the cycles of change, they may disrupt that harmony and unintended consequences may more likely result rather than the willed outcome.[162] Thus the Daodejing says: "act of things and you will ruin them. Grasp for things and you will lose them. Therefore the sage acts with inaction and has no ruin, lets go of grasping and has no loss."[147]

Taoism does not identify one's will as the root problem. Rather, it asserts that one must place their will in harmony with the natural way of the universe.[162] Thus, a potentially harmful interference may be avoided, and in this way, goals can be achieved effortlessly.[163][164] "By wu-wei, the sage seeks to come into harmony with the great Tao, which itself accomplishes by nonaction."[158]

Aspects of the self (xing, xin, and ming)

The Daoist view of the self is a holistic one that rejects the idea of a separate individualized self. As Russell Kirkland writes, Daoists "generally assume that one's 'self' cannot be understood or fulfilled without reference to other persons, and to the broader set of realities in which all persons are naturally and properly embedded."[165]

In Daoism, one's innate or fundamental nature (xing) is ultimately the Dao expressing or manifesting itself as an embodied person. Innate nature is connected with one's heartmind (xin), which refers to consciousness, the heart, and one's spirit.[144] The focus of Daoist psychology is the heartmind (xin), the intellectual and emotional center (zhong) of a person. It is associated with the chest cavity, the physical heart as well as with emotions, thoughts, consciousness, and the storehouse of spirit (shen).[166] When the heartmind is unstable and separated from the Dao, it is called the ordinary heartmind (suxin). On the other hand, the original heartmind (benxin) pervades Dao and is constant and peaceful.[167]

The Neiye (ch.14) calls this pure original heartmind the "inner heartmind", "an awareness that precedes language", and "a lodging place of the numinous".[168] Later Daoist sources also refer to it by other terms like "awakened nature" (wuxing), "original nature" (benxing), "original spirit" (yuanshen), and "scarlet palace".[169] This pure heartmind is seen as being characterized by clarity and stillness (qingjing), purity, pure yang, spiritual insight, and emptiness.[169]

Taoists see life (sheng) as an expression of the Dao. The Dao is seen as granting each person a ming (life destiny), which is one's corporeal existence, one's body and vitality.[144] Generally speaking, Daoist cultivation seeks a holistic psychosomatic form of training that is described as "dual cultivation of innate nature and life-destiny" (xingming shuanxiu).[144] Daoism believes in a "pervasive spirit world that is both interlocked with and separate from the world of humans."[170]

The cultivation of innate nature is often associated with the practice of stillness (jinggong) or quiet meditation, while the cultivation of life-destiny generally revolves around movement based practices (dongong) like daoyin and health and longevity practices (yangsheng).[171]

The Taoist body

Many Taoist practices work with ancient Chinese understandings of the body, its organs and parts, "elixir fields" (dantien), inner substances (such as "essence" or jing), animating forces (like the hun and po), and meridians (qi channels). The complex Daoist schema of the body and its subtle body components contains many parallels with Traditional Chinese medicine and is used for health practices as well as for somatic and spiritual transformation (through neidan – "psychosomatic transmutation" or "internal alchemy").[172] Taoist physical cultivation rely on purfying and transforming the body's qi (vital breath, energy) in various ways such as dieting and meditation.[173]

According to Livia Kohn, qi is "the cosmic energy that pervades all. The concrete aspect of Dao, qi is the material force of the universe, the basic stuff of nature."[174] According to the Zhuangzi, "human life is the accumulation of qi; death is its dispersal."[174] Everyone has some amount of qi and can gain and lose qi in various ways. Therefore, Daoists hold that through various qi cultivation methods they can harmonize their qi, and thus improve health and longevity, and even attain magic powers, social harmony, and immortality.[173] The Neiye (Inward Training) is one of the earliest texts that teach qi cultivation methods.[175]

Qi is one of the Three Treasures, which is a specifically Daoist schema of the main elements in Daoist physical practices like qigong and neidan.[176] The three are: jīng (精, essence, the foundation for one's vitality), qì (氣), and shén (神, spirit, subtle consciousness, a capacity to connect with the subtle spiritual reality).[176][177][178] These three are further associated with the three "elixir fields" (dantien) and the organs in different ways.[179][178]

The body in Taoist political philosophy was important and their differing views on it and humanity's place in the universe were a point of distinction from Confucian politicians, writers, and political commentators.[180] Some Taoists viewed ancestors as merely corpses that were improperly revered and respect for the dead as irrelevant and others within groups that followed these beliefs viewed almost all traditions as worthless.[180]

Ethics

Daoist ethics tends to emphasize various themes from the Daoist classics, such as naturalness (pu), spontaneity (ziran), simplicity, detachment from desires, and most important of all, wu wei.[181] The classic Daoist view is that humans are originally and naturally aligned with Dao, thus their original nature is inherently good. However, one can fall away from this due to personal habits, desires, and social conditions. Returning to one's nature requires active attunement through Daoist practice and ethical cultivation.[182]

Some popular Daoist beliefs, such as the early Shangqing school, do not believe this and believe that some people are irredeemably evil and destined to be so.[183] Many Taoist movements from around the time Buddhist elements started being syncretized with Daoism had an extremely negative view of foreigners, referring to them as yi or "barbarians", and some of these thought of foreigners as people who do not feel "human feelings" and who never live out the correct norms of conduct until they became Taoist.[184] At this time, China was widely viewed by Taoists as a holy land because of influence from the Chinese public that viewed being born in China as a privilege and that outsiders were enemies.[184] Preserving a sense of "Chineseness" in the country and rewarding nativist policies such as the building of the Great Wall of China was important to many Taoist groups.[185]

Foreigners who joined these Taoist sects were made to repent for their sins in another life that caused them to be born "in the frontier wilds" because of Buddhist ideas of reincarnation coming into their doctrines.[184] Some Daoist movements viewed human nature neutrally.[186] However, some of the movements that were dour or skeptical about human nature did not believe that evil is permanent and believed that evil people can become good. Korean Daoists tended to think extremely positively of human nature.[187]

Some of the most important virtues in Daoism are the Three Treasures or Three Jewels (三寶; sānbǎo). These are: ci (慈; cí, usually translated as compassion), jian (儉; jiǎn, usually translated as moderation), and bugan wei tianxia xian (不敢爲天下先; bùgǎn wéi tiānxià xiān, literally "not daring to act as first under the heavens", but usually translated as humility). Arthur Waley, applying them to the socio-political sphere, translated them as: "abstention from aggressive war and capital punishment", "absolute simplicity of living", and "refusal to assert active authority".[188]

Daoism also adopted the Buddhist doctrines of karma and reincarnation into its religious ethical system.[189] Medieval Daoist thought developed the idea that ethics was overseen by a celestial administration that kept records of people's actions and their fate, as well as handed out rewards and punishments through particular celestial administrators.[190]

Soteriology and religious goals

.jpg.webp)

Daoists have diverse religious goals that include Daoist conceptions of sagehood (zhenren), spiritual self-cultivation, a happy afterlife, and/or longevity and some form of immortality (xian, variously understood as a kind of transcendent post-mortem state of the spirit).[191][192]

Daoists' views about what happens in the afterlife tend to include the soul becoming a part of the cosmos[193] (which was often thought of as an illusionary place where qi and physical matter were thought of as being the same in a way held together by the microcosm of the spirits of the human body and the macrocosm of the universe itself, represented and embodied by the Three Pure Ones),[192] somehow aiding the spiritual functions of nature or tiān after death, and/or being saved by either achieving spiritual immortality in an afterlife or becoming a xian who can appear in the human world at will,[194] but normally lives in another plane. "[S]acred forests and[/or] mountains"[195] or a yin-yang,[196][197] yin, yang, or Tao realm[197] inconceivable and incomprehensible by normal humans and even the virtuous Confucius and Confucianists,[198] such as the mental realm sometimes called "the Heavens" where higher, spiritual versions of Daoists such as Laozi were thought to exist when they were alive and absorb "the purest Yin and Yang"[199] were all possibilities for a potential xian to be reborn in. These spiritual versions were thought to be abstract beings that can manifest in that world as mythical beings such as xian dragons who eat yin and yang energy and ride clouds and their qi.[199]

More specifically, possibilities for "the spirit of the body" include "join[ing] the universe after death",[193] exploring[200] or serving various functions in parts of tiān[201] or other spiritual worlds,[200][202] or becoming a xian who can do one or more of those things.[200][201]

Taoist xian are often seen as being eternally young because "of their life being totally at one with the Tao of nature."[203] They are also often seen as being made up of "pure breath and light" and as being able to shapeshift, and some Taoists believed their afterlife natural "paradises" were palaces of heaven.[204]

Taoists who sought to become one of the many different types of immortals, such as xian or zhenren, wanted to "ensure complete physical and spiritual immortality".[39]

In the Quanzhen school of Wang Chongyang, the goal is to become a sage, which he equates with being a "spiritual immortal" (shen xien) and with the attainment of "clarity and stillness" (qingjing) through the integration of "inner nature" (xing) and "worldly reality" (ming).[205]

Those who know the Dao, who flow with the natural way of the Dao and thus embody the patterns of the Dao are called sages or "perfected persons" (zhenren).[206][207] This is what is often considered salvation in Daoist soteriology.[200][208][209] They often are depicted as living simple lives, as craftsmen or hermits. In other cases, they are depicted as the ideal rulers which practice ruling through non-intervention and under which nations prosper peacefully.[206] Sages are the highest humans, mediators between heaven and earth and the best guides on the Daoist path. They act naturally and simply, with a pure mind and with wuwei. They may have supernatural powers and bring good fortune and peace.[210]

Some sages are also considered to have become one of the immortals (xian) through their mastery of the Dao. After shedding their mortal form, spiritual immortals may have many superhuman abilities like flight[202] and are often said to live in heavenly realms.[211][200]

The sages as thus because they have attained the primary goal of Daoism: a union with the Dao and harmonization or alignment with its patterns and flows.[212] This experience is one of being attuned to the Dao and to our own original nature, which already has a natural capacity for resonance (ganying) with Dao.[213] This is the main goal that all Daoist practices are aiming towards and can be felt in various ways, such as a sense of psychosomatic vitality and aliveness as well as stillness and a "true joy" (zhenle) or "celestial joy" that remains unaffected by mundane concerns like gain and loss.[214]

The Taoist quest for immortality was inspired by Confucian emphasis on filial piety and how worshipped ancestors were thought to exist after death.[204]

Becoming an immortal through the power of yin-yang and heaven, but also specifically Taoist interpretations of the Tao, was sometimes thought of as possible in Chinese folk religion,[197] and Taoist thoughts on immortality were sometimes drawn from Confucian views on heaven and its status as an afterlife that permeates the mortal world as well.

Cosmology

Daoist cosmology is cyclic—the universe is seen as being in constant change, with various forces and energies (qi) affecting each other in different complex patterns.[215][216][145] Daoist cosmology shares similar views with the School of Naturalists.[7] Daoist cosmology focuses on the impersonal transformations (zaohua) of the universe, which are spontaneous and unguided.[217]

Livia Kohn explains the basic Daoist cosmological theory as:[218]

the root of creation Dao rested in deep chaos (ch. 42). Next, it evolved into the One, a concentrated state cosmic unity that is full of creative potential and often described in Yijing terms as the Great Ultimate (Taiji). The One then brought forth "the Two", the two energies yin and yang, which in turn merged in harmony to create the next level of existence, "the Three" (yin-yang combined), from which the myriad beings came forth. From original oneness, the world thus continued to move into ever greater states of distinction and differentiation.

The main distinction in Daoist cosmology is that between yin and yang, which applies to various sets of complementary ideas: bright – dark, light – heavy, soft – hard, strong – weak, above – below, ruler – minister, male – female, and so on.[219] Cosmically, these two forces exist in mutual harmony and interdependence.[220] Yin and yang are further divided into five phases (Wu Xing, or five materials): minor yang, major yang, yin/yang, minor yin, major yin. Each of these correlates with a specific substance: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water respectively.[221] This schema is used in many different ways in Daoist thought and practice, from nourishing life (yangsheng) and medicine to astrology and divination.[222]

Daoists also generally see all things as being animated and constituted by qi (vital air, subtle breath), which is seen as a force that circulates throughout the universe and throughout human bodies (as both air in the lungs and as a subtle breath throughout the body's meridians and organs).[223] Qi is in constant transformation between its condensed state (life) and diluted state (potential).[224] These two different states of qi are embodiments of yin and yang,[224] two complementary forces that constantly play against and with each other and where one cannot exist without the other.[225]

Daoist texts present various creation stories and cosmogonies. Classic cosmogonies are non-theistic, presenting a natural undirected process in which an apophatic undifferentiated potentiality (called wuwuji, "without non-differentiation") naturally unfolds into wuji (primordial oneness, "non-differentiation"), which then evolves into yin-yang (taiji) and then into the myriad beings (as in the Daodejing).[226][227] Later medieval models included the idea of a creator God (mainly seen as Lord Lao), representing order and creativity.[226] Daoist cosmology influences Daoist soteriology, which holds that one can "return to the root" (guigen) of the universe (and of ourselves), which is also the Dao—the impersonal source (yuan) of all things.[228]

In Daoism, human beings are seen as a microcosm of the universe,[25] and thus the cosmological forces, like the five phases, are also present in the form of the zang-fu organs.[229] Another common belief is that there are various gods that reside in human bodies.[230] As a consequence, it is believed that a deeper understanding of the universe can be achieved by understanding oneself.[231]

Another important element of Daoist cosmology is the use of Chinese astrology.[215]

Theology

.jpg.webp)

Daoist theology can be defined as apophatic, given its philosophical emphasis on the formlessness and unknowable nature of the Dao, and the primacy of the "Way" rather than anthropomorphic concepts of God. Nearly all the sects share this core belief.[60]

However, Daoism does include many deities and spirits and thus can also be considered animistic and polytheistic in a secondary sense (since they are considered to be emanations from the impersonal and nameless ultimate principle).[232] Some Daoist theology presents the Three Pure Ones at the top of the pantheon of deities, which was a hierarchy emanating from the Dao.[233] Laozi is considered the incarnation of one of the three and worshiped as the ancestral founder of Daoism.[234][235]

Different branches of Daoism often have differing pantheons of lesser deities, where these deities reflect different notions of cosmology.[236] Lesser deities also may be promoted or demoted for their activity.[237] Some varieties of popular Chinese religion incorporate the Jade Emperor (Yü-Huang or Yü-Di), one of the Three Pure Ones, as the highest God. Historical Daoist figures, and people who are considered to have become immortals (xian), are also venerated as well by both clergy and laypeople.[238]

Despite these hierarchies of deities, most conceptions of Dao should not be confused with the Western sense of theism. Being one with the Dao does not necessarily indicate a union with an eternal spirit in, for example, the Hindu theistic sense.[239][162]

Practices

Some key elements of Daoist practice include a commitment to self-cultivation, wu wei, and attunement to the patterns of the Dao.[240] Most Daoists throughout history have agreed on the importance of self cultivation through various practices, which were seen as ways to transform oneself and integrate oneself to the deepest realities.[241]

Communal rituals are important in most Taoist traditions, as are methods of self-cultivation. Daoist self-cultivation practices tend to focus on the transformation of the heartmind together with bodily substances and energies (like jing and qi) and their connection to natural and universal forces, patterns, and powers.[242]

Despite the detachment from reality and dissent from Confucian humanism that the Daodejing teaches, Taoists were and are generally not misanthropes or nihilists and see humans as an important class of things in the world.[186] However, in most Daoist views humans were not held to be especially important in comparison to other aspects of the world and Taoist metaphysics that were seen as equally or more special.[186] Similarly, some Daoists had similar views on their gods or the gods of other religions.[48]

According to Louis Komjathy, Daoist practice is a diverse and complex subject that can include "aesthetics, art, dietetics, ethics, health and longevity practice, meditation, ritual, seasonal attunement, scripture study, and so forth."[240]

Throughout the history of Daoism, mountains have occupied a special place for Daoist practice. They are seen as sacred spaces and as the ideal places for Daoist cultivation and Daoist monastic or eremitic life, which may include "cloud wandering" (yunyou) in the mountains and dwelling in mountain hermitages (an) or grottoes (dong).[243]

Tao can serve as a life energy instead of qi in some Taoist belief systems.

The nine practices

One of the earliest schemas for Daoist practice was the "nine practices" or "nine virtues" (jiǔxíng 九行), which were taught in the Celestial Masters school. These were drawn from classic Daoist sources, mainly the Daodejing, and are presented in the Laojun jinglu (Scriptural Statutes of Lord Lao; DZ 786).[244]

The nine practices are:[245]

- Nonaction (wúwéi 無為)

- Softness and weakness (róuruò 柔弱)

- Guarding the feminine (shǒucí 行守)

- Being nameless (wúmíng 無名)

- Clarity and stillness (qīngjìng 清靜)

- Being adept (zhūshàn 諸善)

- Being desireless (wúyù 無欲)

- Knowing how to stop and be content (zhī zhǐzú 知止足)

- Yielding and withdrawing (tuīràng 推讓)

Rituals

.jpg.webp)

Ancient Chinese religion made much use of sacrifices to gods and ancestors, which could include slaughtered animals (such as pigs and ducks) or fruit. The Daoist Celestial Master Zhang Daoling rejected food and animal sacrifices to the gods. Today, many Daoist Temples reject animal sacrifice.[246] Sacrifices to the deities remains a key element of Daoist rituals however. There are various kinds of Daoist rituals, which may include presenting offerings, scripture reading, sacrifices, incantations, purification rites, confession, petitions and announcements to the gods, observing the ethical precepts, memorials, chanting, lectures, and communal feasts.[247][248]

On particular holidays, such as the Qingming/Ching Ming festival, street parades take place. These are lively affairs that involve firecrackers, the burning of hell money, and flower-covered floats broadcasting traditional music. They also variously include lion dances and dragon dances, human-occupied puppets (often of the "Seventh Lord" and "Eighth Lord"), gongfu, and palanquins carrying images of deities. The various participants are not considered performers, but rather possessed by the gods and spirits in question.[249]

Ethical precepts

Taking up and living by sets of ethical precepts is another important practice in Taoism. By the Tang dynasty, Daoism had created a system of lay discipleship in which one took a set of Ten precepts (Taoism).

The Five precepts (Taoism) are identical to the Buddhist five precepts (which are to avoid: killing [both human and non-human animals], theft, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxicants like alcohol.) The other five were a set of five injuctions:[76]

(6) I will maintain harmony with my ancestors and family and never disregard my kin; (7) When I see someone do good, I will support him with joy and delight; (8) When I see someone unfortunate, I will support him with dignity to recover good fortune; (9) When someone comes to do me harm, I will not harbor thoughts of revenge; (10) As long as all beings have not attained the Dao, I will not expect to do so myself.

Apart from these common ethical precepts, Taoist traditions also have larger sets of precepts that are often reserved for ordained priests or monastics.

Divination and magic

A key part of many Taoist traditions is the practice of divination. There are many methods used by Chinese Taoists including I Ching divination, Chinese astrological divination, feng shui (geomantic divination), and the interpretation of various omens.[250][251]

Mediumship and exorcism is a key element of some Taoist traditions. These can include tongji mediumship and the practice of planchette writing or spirit writing.[251]

Longevity practices

Daoist longevity methods are closely related to ancient Chinese medicine. Many of these methods date back to Tang dynasty figures like alchemist Sun Simiao (582–683) and the Highest Clarity Patriarch Sima Chengzhen (647–735).[252] The goal of these methods range from better health and longevity to immortality. Key elements of these "nourishing life" (yangsheng) methods include: moderation in all things (drink, food, etc.), adapting to the cycles of the seasons by following injunctions regarding healing exercises (daoyin), and breathwork.[253]

A number of physical practices, like modern forms of qigong, as well as modern internal martial arts (neijia) like Taijiquan, Baguazhang, Xingyiquan, and Liuhebafa, are practiced by Daoists as methods of cultivating health and longevity as well as eliciting internal alchemical transformations.[254][255][256] However, these methods are not specifically Daoist and are often practiced outside of Daoist contexts.[257]

Another key longevity method is "ingestion", which focuses on what one absorbs or consumes from one's environment and is seen as affecting what one becomes.[258] Diatectics, closely influenced by Chinese medicine, is a key element of ingestion practice, and there are numerous Daoist diet regimens for different effects (such as ascetic diets, monastic diets, therapeutic diets, and alchemical diets that use herbs and minerals).[259] One common practice is the avoidance of grains (bigu).[260] In certain cases, practices like vegetarianism and true fasting is also adopted (which may also be termed bigu).[261]

"Qi ingestion" (fu qi) is a special practice that entails the absorption of environmental qi and the light of the sun, moon, stars and other astral effulgences and cosmic ethers as a way to enhance health and longevity.[262]

Some Taoists thought of the human body as a spiritual nexus with thousands of shen[178] (often 36,000),[263] gods who were likely thought of as at least somewhat mental in nature because of the word's other meaning of consciousness, that could be communed with by doing various methods to manipulate the yin and yang of the body, as well as its qi.[178] These Taoists also thought of the human body as a metaphorical existence where three "cinnabar fields"[178] that represented a higher level of reality and/or a spiritual kind of cinnabar that does not exist in normal reality. A method of meditation used by these Taoists was "visualizing light" that was thought to be qi or another kind of life energy a Taoist substituted for qi[178] or believed in the existence of instead. The light was then channeled through the three cinnabar fields, forming a "microcosmic orbit" or through the hands and feet for a "macrocosmic orbit".[178]

The 36,000 shen regulated the body and bodily functions through a bureaucratic system "modeled after the Chinese system of government".[263] Death occurs only when these gods leave, but life can be extended by meditating while visualizing them, doing good deeds, and avoiding meat and wine.[263]

Meditation

There are many methods of Daoist meditation (often referred to as "stillness practice", jinggong), some of which were strongly influenced by Buddhist methods.[252][256]

Some of the key forms of Daoist meditation are:[264][256]

- Apophatic or quietistic meditation, which was the main method of classical Daoism and can be found in classic texts like the Zhuangzi, where it is termed "fasting the heartmind" (xinzhai).[265] This practice is also variously termed "embracing the one" (baoyi), "guarding the one" (shouyi), "quiet sitting" (jingzuo), and "sitting forgetfulness" (zuowang).[266] According to Louis Komjathy, this type of meditation "emphasizes emptiness and stillness; it is contentless, non-conceptual, and non-dualistic. One simply empties the heart-mind of all emotional and intellectual content."[266] The texts of classical Daoism state that this meditation leads to the dissolution of the self and any sense of separate dualistic identity.[267] Sima Chengzhen's Zuowang lun is a key text that outlines this method.[267] The practice is also closely connected with the virtue of wuwei (inaction).[268]

- Concentration meditation, focusing the mind on one theme, like the breath, a sound, a part of the body (like one of the dantiens), a diagram or mental image, a deity etc. A subset of this is called "guarding the one", which is interpreted in different ways.

- Observation (guan)—according to Livia Kohn, this method "encourages openness to all sorts of stimuli and leads to a sense of free-flowing awareness. It often begins with the recognition of physical sensations and subtle events in the body but may also involve paying attention to outside occurrences."[269] Guan is associated with deep listening and energetic sensitivity.[270] The term most often refers to "inner observation" (neiguan), a practice that developed through Buddhist influence (see: Vipaśyanā).[256] Neiguan entails developing introspection of one's body and mind, which includes being aware of the various parts of the body as well as the various deities residing in the body.[264]

- Zhan zhuang ("post standing")—standing meditation in various postures.

- Visualization (cunxiang) of various mental images, including deities, cosmic patterns, the lives of saints, various lights in the bodies organs, etc. This method is associated with the Supreme Clarity school, which first developed it.[256]

Alchemy

_Wellcome_L0038974.jpg.webp)

A key element of many schools of Daoism are alchemical practices, which include rituals, meditations, exercises, and the creation of various alchemical substances. The goals of alchemy include physical and spiritual transformation, aligning oneself spiritually with cosmic forces, undertaking ecstatic spiritual journeys, improving physical health, extending one's life, and even becoming an immortal (xian).[271]

Daoist alchemy can be found in early Daoist scriptures like the Taiping Jing and the Baopuzi.[272] There are two main kinds of alchemy, internal alchemy (neidan) and external alchemy (waidan). Internal alchemy (neidan, literally: "internal elixir"), which focuses on the transformation and increase of qi in the body, developed during the late imperial period (especially during the Tang) and is found in almost all Daoist schools today, though it is most closely associated with the Quanzhen school.[273][274] There are many systems of internal alchemy with different methods such as visualization and breathwork.[273] In the late Imperial period, neidan developed into complex systems that drew on numerous elements, including: classic Daoist texts and meditations, yangsheng, Yijing symbology, Daoist cosmology, external alchemy concepts and terms, Chinese medicine, and Buddhist influences.[275] Neidan systems tend to be passed on through oral master-disciple lineages that are often to be secret.[268]

Livia Kohn writes that the main goal of internal alchemy is generally understood as a set of three transformations: "from essence (jing) to energy (qi), from energy to spirit (shen), and from spirit to Dao."[276] Common methods for this include engaging the subtle body and activating the microcosmic orbit.[276][268][178] Louis Komjathy adds that neidan seeks to create a transcendent spirit, usually called the "immortal embryo" (xiantai) or "yang spirit" (yangshen).[275]

Texts

Some religious Daoist movements view traditional texts as scriptures that are considered sacred, authoritative, binding, and divinely inspired or revealed.[277][278][279] However, the Daodejing was originally viewed as "human wisdom" and "written by humans for humans."[279] It and other important texts "acquired authority...that caused them to be regarded...as sacred."[279]

Perhaps the most influential texts are the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi.[280][281]

Daodejing

Throughout the history of Daoism, the Daodejing has been a central text, used for ritual, self-cultivation, and philosophical purposes.[282][283]

According to legend, the Daodejing (Scripture of the Dao and its power, also known as the Laozi) was written by Laozi.[284] Authorship, precise date of origin, and even unity of the text are still subject of debate[285] and will probably never be known with certainty.[286] The earliest manuscripts of this work (written on bamboo tablets) date back to the late 4th century BCE, and these contain significant differences from the later received edition (of Wang Bi c. 226–249).[287][288] Apart from the Guodian text and the Wang Bi edition, another alternative version exists, the Mawangdui Daodejings.[289]

Louis Komjathy writes that the Daodejing is "actually a multi-vocal anthology consisting of a variety of historical and textual layers; in certain respects, it is a collection of oral teachings of various members of the inner cultivation lineages."[283] Meanwhile, Russell Kirkland argues that the text arose out of "various traditions of oral wisdom" from the state of Chu that were written, circulated, edited, and rewritten by different hands. He also suggests that authors from the Jixia academy may have been involved in the editing process.[290]

The Daodejing is not organized in any clear fashion and is a collection of different sayings on various themes.[291] The leading themes of the Daodejing revolve around the nature of Dao, how to attain it and De, the inner power of Dao, as well as the idea of wei wu-wei.[292][293] Dao is said to be ineffable and accomplishes great things through small, lowly, effortless, and "feminine" (yin) ways (which are compared to the behavior of water).[292][293]

Ancient commentaries on the Daodejing are important texts in their own right. Perhaps the oldest one, the Heshang Gong commentary, was most likely written in the 2nd century CE.[294] Other important commentaries include the one from Wang Bi and the Xiang'er commentary.[295]

Zhuangzi