Ampicillin/sulbactam

Ampicillin/sulbactam is a fixed-dose combination medication of the common penicillin-derived antibiotic ampicillin and sulbactam, an inhibitor of bacterial beta-lactamase. Two different forms of the drug exist. The first, developed in 1987 and marketed in the United States under the brand name Unasyn, generic only outside the United States, is an intravenous antibiotic. The second, an oral form called sultamicillin, is marketed under the brand name Ampictam outside the United States. And generic only in the United States, ampicillin/sulbactam is used to treat infections caused by bacteria resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics. Sulbactam blocks the enzyme which breaks down ampicillin and thereby allows ampicillin to attack and kill the bacteria.

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Penicillin antibiotic |

| Sulbactam | Beta-lactamase inhibitor |

| Clinical data | |

| Pronunciation | am pi sill' in and sul bak' tam |

| Trade names | Unasyn |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a693021 |

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular, intraveneous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| | |

Medical uses

Ampicillin/sulbactam has a wide array of medical use for many different types of infectious disease. It is usually reserved as a second-line therapy in cases where bacteria have become beta-lactamase resistant, rendering traditional penicillin-derived antibiotics ineffective. It is effective against certain gram positive bacteria, gram-negative bacteria, and anaerobes.[2]

- Gram-positive bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Staphylococcus epidermidis (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Streptococcus faecalis (Enterococcus), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus viridans.[2][3]

- Gram-negative bacteria: Hemophilus influenzae (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Escherichia coli (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Klebsiella species (all known species are beta-lactamase producing), Proteus mirabilis (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing), Proteus vulgaris, Providencia rettgeri, Providencia stuartii, Morganella morganii, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (beta-lactamase and non-beta-lactamase producing).[2][3]

- Anaerobes: Clostridium species, Peptococcus species, Peptostreptococcus species, Bacteroides species including B. fragilis.[2][3]

Gynecological Infections Ampicillin/sulbactam can be used to treat gynecological infections caused by beta-lactamase producing strains of Escherichia coli, and Bacteroides (including B. fragilis).[2][4]

Bone and joint infections Ampicillin/sulbactam can be used in the treatment of bone and joint infections caused by susceptible beta-lactamase producing bacteria.[5][6][7][8]

Intra-abdominal infections Ampicillin/sulbactam can be used to treat intra-abdominal infections caused by beta-lactamase producing strains of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella (including K. pneumonia), Bacteroides fragilis, and Enterobacter.[2][4]

Skin and skin structure Infections This medication can be used to treat skin and skin structure infections caused from beta-lactamase-producing strains of Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella (including K. pneumoniae), Proteus mirabilis, Bacteroides fragilis, and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus.[2][4] Examples of skin conditions treated with ampicillin-sulbactam are moderate to severe diabetic foot infections and type 1 Necrotizing fasciitis, commonly referred to as "flesh-eating bacteria".[9]

Contraindications

Ampicillin/sulbactam is contraindicated in individuals who have a history of a penicillin allergy. Symptoms of allergic reactions may range from rash to potentially life-threatening conditions, such as anaphylaxis. Patients who have asthma, eczema, hives, or hay fever are more likely to develop undesirable reactions to any of the penicillins.[10]

Adverse effects

Reported adverse events include both local and systemic reactions. Local adverse reactions are characterized by redness, tenderness, and soreness of the skin at the injection site. The most common local reaction is injection site pain. It has been reported to occur in 16% of patients receiving intramuscular injections, and 3% of patients receiving intravenous injections. Less frequently reported side effects include inflammation of veins (1.2%), sometimes associated with a blood clot (3%). The most commonly reported systemic reactions are diarrhea (3%) and rash (2%).[10][11] Less frequent systemic reactions to ampicillin/sulbactam include chest pain, fatigue, seizure, headache, painful urination, urinary retention, intestinal gas, nausea, vomiting, itching, hairy tongue, tightness in throat, reddening of the skin, nose bleeding, and facial swelling. These are reported to occur in less than 1% of patients.[10][11][12]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

The addition of sulbactam to ampicillin enhances the effects of ampicillin. This increases the antimicrobial activity by 4- to 32-fold when compared to ampicillin alone.[13] Ampicillin is a time-dependent antibiotic. Its bacterial killing is largely related to the time that drug concentrations in the body remain above the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The duration of exposure will thus correspond to how much bacterial killing will occur. Various studies have shown that, for maximum bacterial killing, drug concentrations must be above the MIC for 50-60% of the time for the penicillin group of antibiotics. This means that longer durations of adequate concentrations are more likely to produce therapeutic success. However, when ampicillin is given in combination with sulbactam, regrowth of bacteria has been seen when sulbactam levels fall below certain concentrations. As with many other antibiotics, under-dosing of ampicillin/sulbactam may lead to resistance.[14]

Ampicillin/sulbactam has poor absorption when given orally.[13] The two drugs have similar pharmacokinetic profiles that appear unchanged when given together. Ampicillin and sulbactam are both hydrophilic antibiotics and have a volume of distribution (Vd) similar to the volume of extra-cellular body water. The volume that the drug distributes throughout in healthy patients is approximately 0.2 liters per kilogram of body weight. Patients on hemodialysis, elderly patients, and pediatric patients have shown a slightly increased volume of distribution. Using typical doses, ampicillin/sulbactam has been shown to reach desired levels to treat infections in the brain, lungs, and abdominal tissues.[14] Both agents have moderate protein binding, reported at 38% for sulbactam and 28% for ampicillin.15,16 The half-life of ampicillin is approximately 1 hour, when used alone or in combination with sulbactam; therefore it will be eliminated from a healthy person in around 5 hours. It is eliminated primarily by the urinary system, with 75% excreted unchanged in the urine. Only small amounts of each drug were found to be excreted in the bile.[14] Ampicillin/sulbactam should be given with caution in infants less than a week old and premature neonates. This is due to the underdeveloped urinary system in these patients, which can cause a significantly increased half-life for both drugs.16 Based on its elimination, ampicillin/sulbactam is typically given every 6 to 8 hours. Slowed clearance of both drugs has been seen in the elderly, renal disease patients, and critically ill patients on renal replacement therapy. Reduced clearance has been seen in both pediatric and post-operative patients. Adjustments in dosing frequency may be required in these patients due to these changes.[14]

Mechanism of action

Ampicillin/sulbactam is a combination of a β-lactam antibiotic and a β-lactamase inhibitor. Ampicillin works by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) to inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis.[13][14] This causes disruption of the bacterial cell wall and leads to bacterial cell death. However, resistant pathogens may produce β-lactamase enzymes that can inactivate ampicillin through hydrolysis.[14] This is prevented by the addition of sulbactam, which binds and inhibits the β-lactamase enzymes.[13][14] It is also capable of binding to the PBP of Bacteroides fragilis and Acinetobacter spp., even when it is given alone. The activity of sulbactam against Acinetobacter spp. seen in in-vitro studies makes it distinctive compared to other β-lactamase inhibitors, such as tazobactam and clavulanic acid.[14]

Chemistry

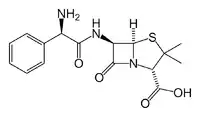

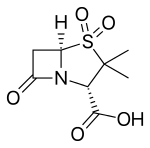

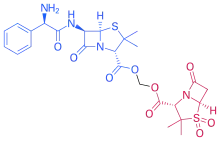

Ampicillin sodium is derived from the basic penicillin nucleus, 6-aminopenicillanic acid. Its chemical name is monosodium (2S, 5R, 6R)-6-[(R)-2-amino-2-phenylacetamido]-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylate. It has a molecular weight of 371.39 grams and its chemical formula is C16H18N3NaO4S.[2] Sulbactam sodium is also a derivative of 6-aminopenicillanic acid. Chemically, it is known as either sodium penicillinate sulfone or sodium (2S, 5R)-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylate 4,4-dioxide. It has a molecular weight of 255.22 grams and its chemical formula is C8H10NNaO5S.[2]

|  |  |

| Skeletal formula of ampicillin | Skeletal formula of sulbactam | Skeletal formula of sultamicillin, highlighting ampicillin in blue and sulbactam in red |

Ampicillin/sulbactam is also used when the cause of an infection is not known (empiric therapy), such as intra-abdominal infections, skin infections, pneumonia, and gynecologic infections. It is active against a wide range of bacterial groups, including Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, and anaerobic bacteria. Importantly, it is not active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and should not be used alone when infection with this organism is suspected or known.

History

The introduction and use of ampicillin alone started in 1961.[15] The development and introduction of this drug allowed the use of targeted therapies against gram-negative bacteria. With the rise of beta-lactamase producing bacteria, ampicillin and the other penicillin-derivatives became ineffective to these resistant organisms. With the introduction of beta-lactamase inhibitors such as sulbactam, combined with ampicillin made beta-lactamase producing bacteria susceptible.[16]

Formulation

Ampicillin-sulbactam only comes in a parenteral formulation to be either used as intravenous or intramuscular injections, and can be formulated for intravenous infusion.[2][17] It is formulated in a 2:1 ratio of ampicillin:sulbactam. The commercial preparations available include:[17]

- 1.5 grams (1 gram ampicillin and 0.5 gram sulbactam)

→Brand names: Unasyn, Unasyn ADD-Vantage, Unasyn Piggyback

- 3 grams (2 grams ampicillin and 1 gram sulbactam)

→Brand names: Unasyn, Unasyn ADD-Vantage, Unasyn Piggyback

- 15 grams (10 grams ampicillin and 5 grams sulbactam)

→Brand name: Unasyn

Society and culture

Names

- Unasyn (US)

- Subacillin (Taiwan)

- Unictam (Egypt)

- Ultracillin (Egypt)

- Fortibiotic

- Sulbin (Egypt)

- Novactam (Egypt)

- Sulbacin (Kenya[18])

References

- "Unasyn- ampicillin sodium and sulbactam sodium injection, powder, for solution". DailyMed. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- Pamphlet Pfizer. Unasyn® (ampicillin sodium/sulbactam sodium) prescribing information. New York, NY; Updated May 2014.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Tests; Approved Standard – 11th ed. CLSI document M02-A11. CLSI, 950 West Valley Rd., Suite 2500, Wayne, PA 19087, 2012.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; 22nd Supplement. CLSI document M100-S22, 2012.>

- Campoli-Richards, Deborah M.; Brogden, Rex N. (June 1987). "Sulbactam/Ampicillin: A Review of its Antibacterial Activity, Pharmacokinetic Properties, and Therapeutic Use". Drugs. 33 (6): 577–609. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733060-00003. PMID 3038500. S2CID 209140985.

- Löffler, L.; Bauernfeind, A.; Keyl, W.; Hoffstedt, B.; Piergies, A.; Lenz, W. (1 November 1986). "An Open, Comparative Study of Sulbactam plus Ampicillin vs. Cefotaxime as Initial Therapy for Serious Soft Tissue and Bone and Joint Infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 8 (Supplement_5): S593–S598. doi:10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_5.s593. PMID 3026009.

- Aronoff, Stepben C.; Scoles, Peter V.; MakJey, Jobn T.; Jacobs, Micbael R.; Blumer, Jeffrey L.; Kalamchi, Ali (1 November 1986). "Efficacy and Safety of Sequential Treatment with Parenteral Sulbactam/Ampicillin and Oral Sultamicillin for Skeletal Infections in Children". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 8 (Supplement_5): S639–S643. doi:10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_5.s639. PMID 3026018.

- Löffler, L.; Bauernfeind, A.; Keyl, W. (1988). "Sulbactam/Ampicillin versus Cefotaxime as Initial Therapy in Serious Soft Tissue, Joint and Bone Infections". Drugs. 35 (Supplement 7): 46–52. doi:10.2165/00003495-198800357-00012. PMID 3265378. S2CID 29850810.

- Fish, Douglas N. (2020). "Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections". Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. ISBN 978-1-260-11681-6.

- Clinical Pharmacology Web site. http://www.clinicalpharmacologyip.com/Forms/Monograph/monograph.aspx?cpnum=35&sec=moncontr&t=0%5B%5D. Accessed November 21, 2014.

- UNASYN [package insert]. Pifzer Inc., New York, NY; April 2007.http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=617. Accessed November 21, 2014.

- Unasyn. Lexi-Drugs Online. LexiComp Web Site. http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/6354#f_adverse-reactions. Accessed November 21, 2014.

- Rafailidis PI, Ioannidou EN, Falagas ME (2007). "Ampicillin/Sulbactam Current Status in Severe Bacterial Infections". Drugs. 67 (13): 1829–1849. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767130-00003. PMID 17722953. S2CID 209145407.

- Adnan S, Paterson DL, Lipman J, Roberts JA (November 2013). "Ampicillin/sulbactam: its potential use in treating infections in critically ill patients". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 42 (5): 384–389. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.07.012. PMID 24041466.

- Acred, P.; Brown, D. M.; Turner, D. H.; Wilson, M. J. (April 1962). "Pharmacology and chemotherapy of ampicillin-a new broad-spectrum penicillin". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 18 (2): 356–369. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1962.tb01416.x. PMC 1482127. PMID 13859205.

- Aronoff, S C; Jacobs, M R; Johenning, S; Yamabe, S (1 October 1984). "Comparative activities of the beta-lactamase inhibitors YTR 830, sodium clavulanate, and sulbactam combined with amoxicillin or ampicillin". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 26 (4): 580–582. doi:10.1128/aac.26.4.580. PMC 179968. PMID 6097169.

- Unasyn. DynaMed Web Site.

- "PPB - eCTD".

External links

- "Ampicillin mixture with Sulbactam". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.