Gardnerella vaginalis

Gardnerella vaginalis is a species of Gram-variable-staining facultative anaerobic bacteria. The organisms are small (1.0–1.5 μm in diameter) non-spore-forming, nonmotile coccobacilli.

| Gardnerella vaginalis | |

|---|---|

| |

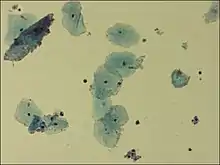

| Microscopic picture of vaginal epithelial clue cells coated with Gardnerella vaginalis, magnified 400 times | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Actinomycetota |

| Class: | Actinomycetia |

| Order: | Bifidobacteriales |

| Family: | Bifidobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Gardnerella |

| Species: | G. vaginalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | |

Once classified as Haemophilus vaginalis and afterwards as Corynebacterium vaginalis, G. vaginalis grows as small, circular, convex, gray colonies on chocolate agar; it also grows on HBT[3] agar. A selective medium for G. vaginalis is colistin-oxolinic acid blood agar.

Clinical significance

G. vaginalis is a facultatively anaerobic Gram-variable rod that is involved, together with many other bacteria, mostly anaerobic, in bacterial vaginosis in some women as a result of a disruption in the normal vaginal microflora. The resident facultative anaerobic Lactobacillus population in the vagina is responsible for the acidic environment. Once the anaerobes have supplanted the normal vaginal bacteria, prescription antibiotics with anaerobic coverage may have to be given to re-establish the equilibrium of the ecosystem. G. vaginalis is not considered the cause of the bacterial vaginosis, but a signal organism of the altered microbial ecology associated with overgrowth of many bacterial species.[4]

While typically isolated in genital cultures, it may also be detected in other samples from blood, urine, and the pharynx. Although G. vaginalis is a major species present in bacterial vaginosis, it can also be isolated from women without any signs or symptoms of infection.

It has a Gram-positive cell wall,[5] but, because the cell wall is so thin, it can appear either Gram-positive or Gram-negative under the microscope. It is associated microscopically with clue cells, which are epithelial cells covered in bacteria.

G. vaginalis produces a pore-forming toxin, vaginolysin, which affects only human cells.[6]

Protease and sialidase enzyme activities frequently accompany G. vaginalis.[7][8][9][10]

Treatment

Methods of antibiotic treatment include metronidazole[11] and clindamycin,[12][13][14] in both oral and vaginal gel/cream forms.

The effectiveness of treating bacterial vaginosis with antibiotics is well documented.

Symptoms

G. vaginalis is associated with bacterial vaginosis,[15] which may be asymptomatic,[16] or may have symptoms including vaginal discharge, vaginal irritation, and a "fish-like" odor. In the amine whiff test, 10% KOH is added to the discharge; a positive result is indicated if a fishy smell is produced. This and other tests can be used to distinguish between vaginal symptoms related to G. vaginalis and those caused by other organisms, such as Trichomonas and Candida albicans, which are similar and may require different treatment. Trichomonas vaginalis and G. vaginalis have similar clinical presentations and can cause a frothy gray or yellow-green vaginal discharge, pruritus, and produce a positive "whiff-test". The two can be distinguished using a wet-mount slide, where a swab of the vaginal epithelium is diluted and then placed onto a slide for observation under a microscope. Gardnerella reveals a classic "clue cell" under the microscope, showing bacteria adhering to the surface of squamous epithelial cells.

References

- Gardner HL, Dukes CD (1955). "Haemophilus vaginalis vaginitis. A newly defined specific infection previously classified 'Non-specific vaginitis'". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 69 (5): 962–976. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(55)90095-8. PMID 14361525.

- J. R. Greenwood; M. J. Pickett (January 1980). "Transfer of Haemophilus vaginalis Gardner and Dukes to a New Genus, Gardnerella: G. vaginalis (Gardner and Dukes) comb. nov". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 30 (1): 170–178. doi:10.1099/00207713-30-1-170.

- Totten, P A; Amsel, R; Hale, J; Piot, P; Holmes, K K (January 1982). "Selective differential human blood bilayer media for isolation of Gardnerella (Haemophilus) vaginalis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 15 (1): 141–147. doi:10.1128/jcm.15.1.141-147.1982. ISSN 0095-1137. PMC 272039. PMID 6764766.

- "Bacterial Vaginosis Infection: Symptoms and Treatment". eMedicineHealth.

- Harper, J; Davis, G (1982). "Cell Wall Analysis of Gardnerella vaginalis". Int J Syst Bacteriol. 32: 48–50. doi:10.1099/00207713-32-1-48.

- Gelber, S. E.; Aguilar, J. L.; Lewis, K. L. T.; Ratner, A. J. (2008). "Functional and Phylogenetic Characterization of Vaginolysin, the Human-Specific Cytolysin from Gardnerella vaginalis". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (11): 3896–3903. doi:10.1128/JB.01965-07. PMC 2395025. PMID 18390664.

- Lopes dos Santos Santiago, G.; Deschaght, P.; Aila, N. El; Kiama, T. N.; Verstraelen, H.; Jefferson, K. K.; Temmerman, M.; Vaneechoutte, M. (2011). "Gardnerella vaginalis comprises three distinct genotypes of which only two produce sialidase". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204: 450.

- Harwich, M. D. Jr.; Alves, J. M.; Buck, G. A.; Strauss, J. F.; Patterson, J. L.; Oki, A. T.; Girerd, P. H.; Jefferson, K. K. (2010). "Drawing the line between commensal and pathogenic Gardnerella vaginalis through genome analysis and virulence studies". BMC Genomics. 11: 375. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-375. PMC 2890570. PMID 20540756.

- von Nicolai, H.; Hammann, R.; Salehnia, S.; Zilliken, F. (1984). "A newly discovered sialidase from Gardnerella vaginalis". Zentralbl. Bakteriol. Mikrobiol. Hyg. A. 258 (1): 20–26. doi:10.1016/s0176-6724(84)80003-6. PMID 6335332.

- Yeoman, C. J.; Yildirim, S.; Thomas, S. M.; Durkin, A. S.; Torralba, M.; Sutton, G.; Buhay, C. J.; Ding, Y.; Dugan-Rocha, S. P.; Muzny, D. M.; Qin, X.; Gibbs, R. A.; Leigh, S. R.; Stumpf, R.; White, B. A.; Highlander, S. K.; Nelson, K. E.; Wilson, B. A. (2010). "Comparative genomics of Gardnerella vaginalis strains reveals substantial differences in metabolic and virulence potential". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e12411. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512411Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012411. PMC 2928729. PMID 20865041.

- Jones BM, Geary I, Alawattegama AB, Kinghorn GR, Duerden BI (August 1985). "In-vitro and in-vivo activity of metronidazole against Gardnerella vaginalis, Bacteroides spp. and Mobiluncus spp. in bacterial vaginosis". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 16 (2): 189–97. doi:10.1093/jac/16.2.189. PMID 3905748.

- "Clindamycin" (PDF). Davis. 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- Khan, F. Z. (2011). "Microbial Infections in females of childbearing age and therapeutic interventions". Rawal Medical Journal. 36 (3): 178–181.

- Ferris, D.G.; Litaker, M.S.; Woodward, L.; Mathis, D.; Hendrich, J. (1995). "Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a comparison of oral metronidazole, metronidazole vaginal gel, and clindamycin vaginal cream". The Journal of Family Practice. 41 (5): 443–449. PMID 7595261.

- Pleckaityte, Milda; Zilnyte, Milda; Zvirbliene, Aurelija (2012). "Insights into the CRISPR/Cas system of Gardnerella vaginalis". BMC Microbiology. 12: 301. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-301. PMC 3559282. PMID 23259527.

- Schwebke, Jane R. (2000). "Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 183 (6): 1434–1439. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.107735. PMID 11120507.

External links

- Gardnerella at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Type strain of Gardnerella vaginalis at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase