Lente insulin

Lente insulin (from Italian lento, "slow"; also called insulin zinc suspension) was an intermediate duration insulin that is no longer used in humans.[1] The onset of lente insulin is one to two hours after the dose is administered, and the peak effect is approximately 8 to 12 hours after administration, with some effects lasting over 24 hours.[2]

Lente insulin products, along with other insulin analogs in the same family, were discontinued by their manufacturers in the mid-2000s, and are no longer permitted to be marketed for use in humans in the US.[3][4] This was in part because health care providers began to favor more predictable forms of insulin, such as recombinant NPH insulin.[5]

History

Lente insulin arose from research into ways to alter the pharmacokinetics of bovine or porcine insulin products. Prior to the late 1940s, insulin products were derived from pork or beef sources, and then used virtually unaltered as "short-acting" insulin products. It was known by 1950 that the addition of protamine or zinc could alter the duration of action of these insulin products, and in 1952, K. Hallas-Møller at Novo Nordisk produced the first commercial insulin zinc suspension for use in humans.[6] For decades, lente insulin was used as a basal insulin, designed to mimic the body's continual slow release of insulin throughout the day. Compared to NPH insulin, lente insulin has a similar but more protracted loss of action after a dose is administered.[7]

In the 1990s, recombinant DNA technology allowed for the mass production of the human insulin protein in yeast or bacteria. This led to formulations of recombinant lente human insulin products by the early 2000s.[8] However, lente insulin began to fall out of favor with doctors in the mid-2000s, when insulin analogues such as glargine began to be approved. Insulin analogues made by recombinant DNA production methods have less variation in their strength and purity between doses and batches. Furthermore, while lente insulin (and NPH) have a definitive peak in effect, insulin analogs have a much less pronounced peak, making for more predictable effects and less risk of hypoglycemia.[9]

Veterinary use

After the discontinuation of lente insulin for human use, the FDA approved a veterinary porcine-derived lente insulin (vetsulin®,[10] Merck Animal Health) for daily use in dogs or twice daily use in cats. Insulin analogs used in humans after the discontinuation of lente insulin have not yet been proven to provide the same benefits and predictability as lente insulin in cats and dogs.[11] For this and other reasons, lente insulin is still commonly used in both dogs and cats.[11]

Adverse effects

Hypoglycemia

The primary adverse effect of any insulin product is hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar. Hypoglycemia can manifest as dizziness, disorientation, trouble speaking, and changes in mental status. In severe cases, hypoglycemia can lead to loss of consciousness if not treated.[12] As lente insulin continues to be absorbed in the body for hours after use, these signs and symptoms may be delayed from the time of administration and begin with little or no warning.

Hypersensitivity

Lente insulin is a combination of porcine and bovine insulin products which are filtered and combined with zinc to form the suspension. Even product that is filtered very well is still of animal origin, and there is a chance the body may recognize the foreign protein as such and form antibodies against it. These reactions are slightly more likely with lente insulin than with insulin derived from a single source as lente insulin contains bovine insulin which is more immunogenic than porcine insulin.[7]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

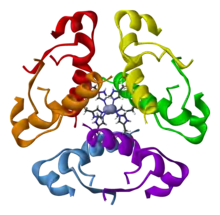

Insulin is a protein normally produced in the pancreas which regulates metabolic processes throughout the body. The primary role of insulin is to increase the metabolism of glucose, storage of energy in adipose tissue, and decrease the body's own production of glucose.[13]

Pharmacokinetics

The half life of endogenous insulin once it enters the bloodstream is 4 to 6 minutes.[14] This allows the endocrine system to rapidly adapt to changing conditions within the body. Exogenous insulin, however, would not be effective with a short half life, as it would require continuous injection or infusion to have the desired effect. While it is difficult to change the rate at which the protein is metabolized in the bloodstream, it is possible to alter how fast the protein is absorbed from the site of injection in various ways.[7]

Lente insulin was formulated by the addition of zinc to the crude porcine and bovine insulin extracts, which causes the insulin protein to form larger crystals which dissolve into the body slower upon injection.[7] This means that while the insulin in the bloodstream is still metabolized in 4–6 minutes, more insulin is continually being absorbed from the dose injected for hours after administration. Compared to NPH insulin, another intermediate acting insulin, up to 40% of the dose of lente insulin may remain unabsorbed for over 24 hours after administration. The variation in absorption between doses in the same patient of lente insulin is comparable to that of insulin NPH.[7]

The distribution of insulin is not well understood, but it is known that it is heavily bound to receptors throughout the body (approximately 80% to receptors on liver cells) and metabolized in large part by phase one processes in the liver. Of the approximately 71-minute estimated lifetime of an insulin molecule, over 60 minutes is spent attached to a liver receptor. In addition, circulating unbound insulin is excreted and reabsorbed by the kidneys and broken down in the lysosomes. The remainder of metabolism of insulin molecules is via intracellular proteolysis via insulysin and related enzymes.[14]

Manufacturing

Commercial preparations of lente insulin are standardized to 30% semilente (amorphous precipitates of insulin), and 70% ultralente (crystallized insulin).[15] In early versions, the semilente insulin was extracted from pigs, and the ultralente insulin was extracted from cows.[15]

Society and culture

Brand names of lente insulin that have been discontinued include Iletin (animal), and HumulinL/NovolinL (human). Lente insulin is currently produced under the brand name vetsulin for veterinary use in dogs and cats with diabetes.[10]

References

- Holmberg, Monica (1 October 2006). "An Overview of Insulin Breakthroughs". Pharmacy Times. Vol. 2006, no. 10. Pharmacy & Healthcare Communications. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Owens, David R. (June 2011). "Insulin Preparations with Prolonged Effect". Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 13 (S1): S-5–S-14. doi:10.1089/dia.2011.0068. PMID 21668337.

- Federal Register Doc. E9-2901

- Federal Register Doc. 2011-14164

- "Discontinuation of Humulin®U ULTRALENTE" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Hallas-Møller, K.; Petersen, K.; Schlichtkrull, J. (1952). "Crystalline and Amorphous Insulin-Zinc Compounds with Prolonged Action". Science. 116 (3015): 394–398. Bibcode:1952Sci...116..394H. doi:10.1126/science.116.3015.394. ISSN 0036-8075. JSTOR 1680777. PMID 12984132.

- Deckert, T. (1 September 1980). "Intermediate-acting Insulin Preparations: NPH and Lente". Diabetes Care. 3 (5): 623–626. doi:10.2337/diacare.3.5.623. PMID 7192205. S2CID 22310080.

- Landgraf, Wolfgang; Sandow, Juergen (2016). "Recombinant Human Insulins – Clinical Efficacy and Safety in Diabetes Therapy". European Endocrinology. 12 (1): 12–17. doi:10.17925/EE.2016.12.01.12. PMC 5813452. PMID 29632581.

- Horvath, Karl; Jeitler, Klaus; Berghold, Andrea; Ebrahim, Susanne H; Gratzer, Thomas W; Plank, Johannes; Kaiser, Thomas; Pieber, Thomas R; Siebenhofer, Andrea (18 April 2007). "Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005613. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005613.pub3. PMID 17443605.

- "Compendium of Veterinary Products". merckusa.cvpservice.com.

- Behrend, Ellen; Holford, Amy; Lathan, Patty; Rucinsky, Renee; Schulman, Rhonda (January 2018). "2018 AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 54 (1): 4–6. doi:10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6822. PMID 29314873. S2CID 43327430.

- "Hypoglycemia". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. October 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015.

- Dimitriadis, George; Mitrou, Panayota; Lambadiari, Vaia; Maratou, Eirini; Raptis, Sotirios A. (August 2011). "Insulin effects in muscle and adipose tissue". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 93: S52–S59. doi:10.1016/S0168-8227(11)70014-6. PMID 21864752.

- Duckworth, William C.; Bennett, Robert G.; Hamel, Frederick G. (1 October 1998). "Insulin Degradation: Progress and Potential*". Endocrine Reviews. 19 (5): 608–624. doi:10.1210/edrv.19.5.0349. PMID 9793760.

- Wittlin, Steven D.; Woehrle, Hans J.; Gerich, John E. (2002). "Insulin Pharrmacokinetics". In Leahy, Jack L.; Cefalu, William T. (eds.). Insulin therapy. New York: CRC Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-8247-4462-4. OCLC 52707816.