Hashimoto's encephalopathy

| Hashimoto's encephalopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, Nonvasculitic autoimmune meningoencephalitis, Encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, EAATD | |

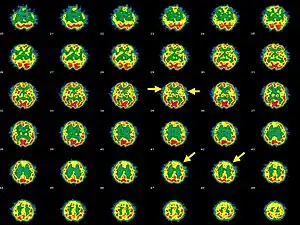

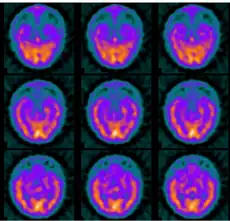

| |

| Brain SPECT transaxial images of a patient afflicted with Hashimoto's encephalopathy. | |

Hashimoto's encephalopathy, also known as steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT), is a neurological condition characterized by encephalopathy, thyroid autoimmunity, and good clinical response to corticosteroids. It is associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and was first described in 1966. It is sometimes referred to as a neuroendocrine disorder, although the condition's relationship to the endocrine system is widely disputed. It is recognized as a rare disease by the NIH Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center.[1]

Almost 200 case reports of this disease have been published[1].

Signs and symptoms

Presentation of Hashimoto's encephalopathy may include:[1][2]

- Personality changes

- Aggression

- Delusional behavior

- Concentration and memory problems

- Depression

- Hyperreflexia

- Poor appetite

- Myoclonus

- Lack of coordination

- Slurred speech

- Psychosis

- Seizures

- Sleep abnormalities

- Paralysis

- Status epilepticus

A relapsing encephalopathy occurs in association with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, with high titers of antithyroid antibodies.[3] Onset is often gradual and may go unnoticed by the individual and close associates to the individual; symptoms sometimes resolve themselves, leaving the individual undiagnosed.[4]

Cause

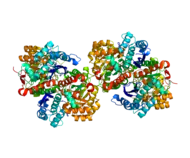

The cause is not known, but is thought to be an autoimmune disorder[2]Consistent with this hypothesis, autoantibodies to alpha-enolase have been found to be associated with Hashimoto's encephalopathy.[5]

Mechanism

Enolase has been found in the brain tissue of individuals with HE and is the penultimate step in glycolysis, if it were inhibited, one would expect decreased energy production by each cell, leading to resulting atrophy of the affected organ.This would occur most likely through each cell shrinking in size in response to the energy deficit.This may occur as a result of enough ATP not being available to maintain cellular functions - notably, failure of the Na/K ATPase, resulting in a loss of the gradient to drive the Na/Ca antiporter, which normally keeps Ca+

2 out of cells so it does not build to toxic levels that will rupture cell lysosomes leading to apoptosis. An additional feature of a low-energy state is failure to maintain axonal transport via dynein/kinesin ATPases, which in many diseases results in neuronal injury to both the brain and/or periphery.[6][7][8]

Pathology

Very little is known about the pathology of Hashimoto's encephalopathy, post mortem studies of some individuals have shown lymphocytic vasculitis of venules and veins in the brain stem [9]As mentioned above, autoantibodies to alpha-enolase associated with Hashimoto's encephalopathy have thus far been the most hypothesized mechanism of injury.[5]

Diagnosis

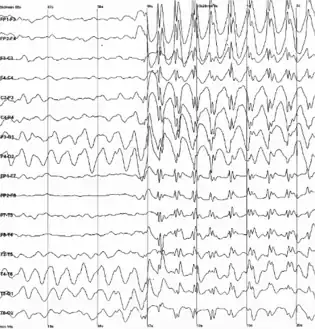

In terms of the diagnosis of Hashimoto's encephalopathy electroencephalogram studies, while almost always abnormal, are usually not diagnostic. The most common findings are diffuse or generalized slowing or frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Prominent triphasic waves, focal slowing, epileptiform abnormalities, and photoparoxysmal and photomyogenic responses may be seen.[10]

Laboratory findings are: increased liver enzyme levels, increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate.[11]

Cerebrospinal fluid findings:[12]

- Raised protein

- May contain antithyroid antibodies

- Magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities consistent with encephalopathy

- Cell count normal

- Cerebral angiography is normal

Thyroid hormone abnormalities are common : [10]

- Subclinical hypothyroidism

- Overt hypothyroidism

- Hyperthyroidism

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Because most individuals respond to corticosteroids or immunosuppressant treatment, this condition is now also referred to as steroid-responsive encephalopathy.Initial treatment is usually with oral prednisone (30 mg/day[16]) or high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day) for 5 days.[11][1] Thyroid hormone treatment is also included if required, failure of some individuals to respond to this first-line treatment has produced a variety of alternative treatments, including azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, periodic intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange.Seizures, if present, are controlled with typical antiepileptic agents.[15][2]

Prognosis

Duration of treatment is usually between 2 and 25 years. Earlier reports suggested that 90% of cases stay in remission after discontinuation of treatment, but this is at odds with more recent studies, which suggest that relapse commonly occurs after initial high-dose steroid treatment.[17][18]

Epidemiology

The prevalence has been estimated to be 2.1/100,000[19] with a male-to-female ratio of 1:4. The mean age of onset for Hashimoto's encephalopathy is 44 years old.[6][20]

History

The first case of HE (Hashimoto's encephalopathy) was described by Brain et al. in 1966.[21]

The patient was a 48-year-old man with hypothyroidism, multiple episodes of encephalopathy, stroke-like symptoms, and Hashimoto's thyroiditis confirmed by elevated antithyroid antibodies.[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Hashimoto encephalopathy | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Hashimoto Encephalopathy". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ↑ Aminoff, Michael J.; Josephson, S. Andrew (29 January 2021). Aminoff's Neurology and General Medicine. Academic Press. p. 1016. ISBN 978-0-12-819307-5. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Mahmoud, Sakr (22 November 2019). Diagnosing and Managing Hashimoto?s Disease: Emerging Research and Opportunities: Emerging Research and Opportunities. IGI Global. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-5225-9657-8. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- 1 2 Fujii A, Yoneda M, Ito T, Yamamura O, Satomi S, Higa H, Kimura A, Suzuki M, Yamashita M, Yuasa T, Suzuki H, Kuriyama M (May 2005). "Autoantibodies against the amino terminal of alpha-enolase are a useful diagnostic marker of Hashimoto's encephalopathy". J. Neuroimmunol. 162 (1–2): 130–6. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.02.004. PMID 15833368. S2CID 43249019.

- 1 2 Mocellin, Ramon; Walterfang, Mark; Velakoulis, Dennis (2007). "Hashimoto's encephalopathy : epidemiology, pathogenesis and management". CNS drugs. 21 (10): 799–811. doi:10.2165/00023210-200721100-00002. ISSN 1172-7047. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Payer, Juraj; Petrovic, Tomas; Lisy, Lubomir; Langer, Pavel (2012). "Hashimoto Encephalopathy: A Rare Intricate Syndrome". International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 10 (2): 506–514. doi:10.5812/ijem.4174. ISSN 1726-913X. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ↑ Young, G. Bryan; Wijdicks, Eelco F. M. (13 August 2008). Disorders of Consciousness. Newnes. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-444-51895-8. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ↑ Sakr, Mahmoud F. (27 July 2020). Thyroid Disease: Challenges and Debates. Springer Nature. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-030-48775-1. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- 1 2 Li, Jie; Li, Fengzhen (8 May 2019). "Hashimoto's Encephalopathy and Seizure Disorders". Frontiers in Neurology. 10. doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00440. ISSN 1664-2295. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- 1 2 Castillo, Pablo; Woodruff, Bryan; Caselli, Richard; Vernino, Steven; Lucchinetti, Claudia; Swanson, Jerry; Noseworthy, John; Aksamit, Allen; Carter, Jonathan; Sirven, Joseph; Hunder, Gene; Fatourechi, Vahab; Mokri, Bahram; Drubach, Daniel; Pittock, Sean; Lennon, Vanda; Boeve, Brad (1 February 2006). "Steroid-Responsive Encephalopathy Associated With Autoimmune Thyroiditis". Archives of Neurology. 63 (2): 197. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.2.197. ISSN 0003-9942. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ Piña-Garza, Eric J. (30 April 2013). Fenichel's Clinical Pediatric Neurology: A Signs and Symptoms Approach (Expert Consult - Online and Print). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4557-2376-8. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Aminoff's neurology and general medicine (Fifth ed.). Amesterdam. 2014. pp. 329–350. ISBN 978-0-12-407710-2. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-20.

- ↑ Autoimmune Neurology. Elsevier. 11 March 2016. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-444-63446-7. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- 1 2 Zhu, Yifei; Yang, Haiqing; Xiao, Fulong (15 September 2015). "Hashimoto's encephalopathy: a report of three cases and relevant literature reviews". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 8 (9): 16817–16826. ISSN 1940-5901. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ de Holanda, Narriane Chaves P.; de Lima, Denise Dantas; Cavalcanti, Taciana Borges; Lucena, Cynthia Salgado; Bandeira, Francisco (2011). "Hashimoto's encephalopathy: systematic review of the literature and an additional case". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 23 (4): 384–390. doi:10.1176/jnp.23.4.jnp384. ISSN 1545-7222. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Castillo P, Woodruff B, Caselli R, et al. (February 2006). "Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis". Archives of Neurology. 63 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.2.197. PMID 16476807.

- ↑ Flanagan EP, McKeon A, Lennon VA, et al. (October 2010). "Autoimmune dementia: clinical course and predictors of immunotherapy response". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 85 (10): 881–97. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0326. PMC 2947960. PMID 20884824.

- ↑ Ferracci F, Bertiato G, Moretto G (February 2004). "Hashimoto's encephalopathy: epidemiologic data and pathogenetic considerations". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 217 (2): 165–8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2003.09.007. PMID 14706219. S2CID 19827218.

- ↑ Biller, Jose; Ferro, José M. (9 January 2014). Neurologic Aspects of Systemic Disease, Part II. Newnes. p. 721. ISBN 978-0-7020-4433-5. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- 1 2 Brain L, Jellinek EH, Ball K (September 1966). "Hashimoto's disease and encephalopathy". The Lancet. 2 (7462): 512–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(66)92876-5. PMID 4161638.

Further reading

- Hashimoto's Encephalopathy SREAT Alliance (2013). Understanding Hashimoto's Encephalopathy: A Guide for Patients, Families, and Caregivers, Featuring Stories of HE Patients from Around the World. North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781484883099. OCLC 890816771.

- Schiess N, Pardo CA (October 2008). "Hashimoto's encephalopathy". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1142 (1): 254–65. Bibcode:2008NYASA1142..254S. doi:10.1196/annals.1444.018. PMID 18990131. S2CID 1312798.

- Taylor SE, Garalda ME, Tudor-Williams G, Martinez-Alier N (February 2003). "An organic cause of neuropsychiatric illness in adolescence". The Lancet. 361 (9357): 572. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12517-2. PMID 12598143. S2CID 35053683.

| Classification |

|---|